Abstract

Background:

Determining the risk factors in developing or increasing the relapses of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) may help health and preventive systems to launch new programs. Up to 90% of normal population changes to seropositive for BK virus by the age of 10 years. Whether this oncogenic virus is responsible for evolving ALL is unclear. In this study, we evaluated the excretion of urinary BK virus in newly diagnosed children with ALL compared with normal population.

Methods:

This case–control study was carried out on 62 participants (32 ALL patients and 32 normal subjects), aged 1–18 years, in Saint Al-Zahra and Sayyed-Al-Shohada University Hospitals, Isfahan, Iran. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method was used to detect the BK virus in specimens. PCR amplification was performed using specific primers of PEP-1 (5′-AGTCTTTAGGGTCTTCTACC-3′) and PEP-2 (5′-GGTGCCAACCTATGGAACAG-3′).

Results:

Thirty-five out of 62 participants (54.8%) were males and the remaining were females. The mean duration of disease was 9.6 ± 9.69 months. Central nervous system (CNS) relapse was seen in 29% of the patients. Positive PCR for urine BK virus was seen in three children with ALL (9.7%). No positive result for urine BKV was achieved in the control group. However, Fisher's exact test did not show any significant difference between the two groups (P > 0.05). In addition, there was no significant correlation between BKV positivity and frequency of relapses.

Conclusion:

To demonstrate the role of BK virus in inducing ALL or increasing the number of relapses, prospective studies on larger scale of population and evaluating both serum and urine for BK virus are recommended.

Keywords: BK virus, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, children

INTRODUCTION

Polyomavirus BK virus, a small DNA virus, belongs to the polyomaviridae family. This family includes at least two additional viruses: the JC virus (JCV) and the simian virus SV40.[1] Agnoprotein, a subunit of polyomavirus genome, not only contains important regulatory elements but also its interaction with viral capsid proteins results in the formation of promyelocytic leukemia bodies.[2–4] It has been reported that up to 90% of normal population changes to seropositive status between 5 and 10 years of age.[5–8] Immunocompromised situations such as solid or bone marrow organ transplantation and receiving immunosuppressant medications may activate latent BK virus infection.[4,9–11] While renal dysfunction is more prevalent in kidney transplant recipients, hemorrhagic cystitis is more possible to occur in bone marrow transplanted patients.[1] Polyomavirus tumor antigen (T Ag) sequences, especially SV40 specific, were detected in non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[12] Furthermore, it has been assumed that the rate of multiple virus isolation is significantly greater in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) than normal population.[13] It has been still debated whether BKV infection may increase the risk of lymphoblastic leukemia or not. Considering the scarce data about the incidence of BKV infection in children with ALL, we conducted this study on the newly diagnosed leukemic children to investigate the urinary excretion of BKV and its possible relation with triggering the disease.

METHODS

This cross-sectional case–control study was carried out on 62 participants, aged 1–18 years, in Saint Al-Zahra Hospital, Isfahan, Iran. The participants included 32 cases of children newly diagnosed with ALL and 32 normal children referred to the hospitals for routine health evaluation as the control group.

Inclusion criteria for the case group:

Age less than 18 years at the time of diagnosis.

Newly diagnosed as ALL (less than 3 months).

No evidence of urinary tract infection at the time of urine sampling.

Inclusion criteria for the control group:

No evidence of chronic diseases.

No past history of recent treatment with steroids (oral or inhaler).

No history of recent urinary tract infection.

No gross anatomical and physical abnormality or syndromic phenotypes.

No sign of failure to thrive and malnutrition.

The first fasting urine sample was collected to increase the chance of finding urinary epithelial cells. The samples were carried on ice to the laboratory immediately. Urine specimens (15 ml) were centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 15 min. The sediments were frozen at –70°C.

Genomic DNA was extracted from the thawed samples by phenol/chloroform method.[1] The extracted DNA in TE buffer was stored at –20°C until analysis by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method. The quality of the DNA was evaluated by PCR using beta-globin specific primers.[14] A PCR method was used to detect the BK virus in specimens. PCR amplification was performed using specific primers of PEP- 1 (5′-AGTCTTTAGGGTCTTCTACC-3′) and PEP-2 (5′-GGTGCCAACCTATGGAACAG-3′).[15] Each PCR reaction was carried out in a total volume of 50 μl containing 1× PCR buffer, 1 mM MgCl2, 2.5 pmol of each primer, 0.2 mmol dNTP, 1.5 U Taq DNA polymerase (Sinagene, Tehran, Iran), 10 μl template DNA, and distilled water, to a total volume of 50 μl. The PCR was performed in thermal cycler Master (Eppendorf, Germany). The amplification conditions were as follows: 94°C for 5 min; followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, 72°C for 2 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. Purified BKV genome as positive control and distilled water as negative control were included in all runs. PCR products were analyzed on agarose gel electrophoresis followed by ethidium bromide staining.

RESULTS

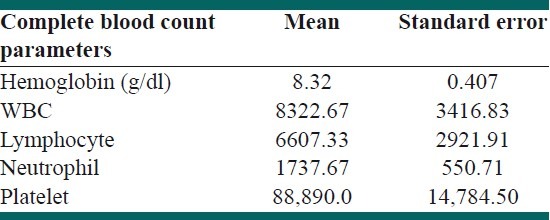

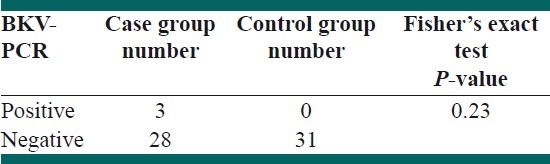

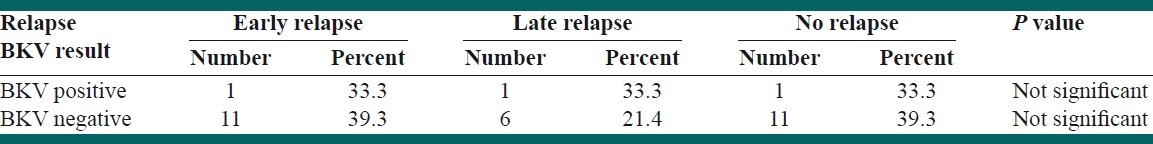

Thirty-five out of 62 participants (54.8%) were males and the remaining were females. The mean age of diagnosis of ALL in the case group was 6.25 ± 3.58 years. However, the mean ages of urine sampling for BKV in case and control groups were not significantly different (6.97 ± 4.11 years vs. 7.13 ± 3.14 years, respectively; P > 0.05). The mean duration of follow-up was 9.6 ± 6.09 months. Central nervous system (CNS) disease was reported in 29% of the patients. CNS relapse was reported in 12.7% of the patients. There was a significant correlation between the frequency of radiotherapy with CNS relapses and death (P < 0.001). The most prevalent abnormalities in complete blood count (CBC) results were anemia and thrombocytopenia. In addition, low hemoglobin level significantly correlated with the overall mortality (P < 0.05). However, leukocytosis was not a common finding in our patients [Table 1]. Conventional PCR on the first morning urine samples revealed positive results in three children with ALL (9.7%). No positive PCR result was achieved in the control group. However, Fisher's exact test did not show any significant difference between the two groups (P > 0.05) [Table 2]. In addition, there was no significant correlation between BKV positivity and frequency of relapses [Table 3]. Furthermore, the mean time of diagnosis ALL was not different between BKV positive and negative groups (P > 0.05). There was no correlation between urine BKV positivity and CBC parameter abnormalities (data not shown). Eight patients out of 32 (25.8%) died before the survey was completed.

Table 1.

Blood cell parameters in children with ALL

Table 2.

BKV-PCR results in two groups

Table 3.

Frequency of relapses between BKV positive and negative groups

DISCUSSION

According to our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating urinary BKC excretion in children newly diagnosed with ALL. We demonstrated the presence of BKV in urine of this group of patients before the prescribed medications changed the patients’ immunostatus.

It has been demonstrated that cells infected with BKV undergo two different processes: cell lysis and cell transformation or abortive infection.[16–18] Urogenital and mononuclear cells have been shown as the sites for dissemination and perseverance of BKV.[19–21] The in vitro and in vivo behaviors of BKV make the virus notorious as a tumor virus. Detecting BKV in peripheral blood cells has led to the hypothesis of involvement of BKV in lymphoma.[19,20] In animal models, BKV inoculation resulted in evolving different types of tumors.[18–22] Immunocompromised conditions resulting from diseases and/or numerous immunosuppressor medications reactivate BKV infection.[23] JC virus, another member of the polyomaviridae family, has been associated with human cancers. However, a large percentage of the normal population is seropositive for JCV up to adolescence.[24] Transcription and DNA replication of JCV is regulated by T Ag protein. The presence of JCV and its regulatory protein, T Ag, in tumoral cells has led to hypothesize that JCV infection and T Ag might cause abnormal cell growth and solid tumor formation such as gastrointestinal cancers, brain tumors, and lung cancers.[24–31]

ALL is the most common malignancy in children with a peak incidence in 2–5 years of age. The mean age of our patients was in the upper limit of the mentioned range. Relapse of ALL is not uncommon in children. Bone marrow and CNS are the most common sites of relapses.[32] Our patients frequently experienced relapses. There was a correlation between frequency of relapses, CNS relapses, and overall mortality. All of our patients had CNS relapses. Although isolated CNS relapses have been shown with better survival, bone marrow relapse makes the outcome poorer.[33] The mortality of our patients correlated with CNS relapses and the frequency of radiotherapy courses. Most of our patients who died had simultaneous bone marrow and CNS relapses.

Numerous studies have shown the role of infections in developing ALL.[34,35] Regarding the presence of BKV-DNA sequences in normal human tissues and the expression of T Ag (BKV viral protein) in neoplastic tissues, BKV has been assumed to have the potential ability to act as a carcinogen.[36] In addition, Jiang et al. revealed the interaction between promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies (PML-NBs) and BKV. According to their study, BKV infection is accompanied with reduction in PML-NBs number and enlargement in size. Therefore, the reorganization of PML-NBs used by BKV inactivates antiviral function of PML-NBs.[37] Mc Nally and colleagues reported a significant cross-clustering between leukemia and CNS tumors. Furthermore, they proposed a consistency between infectious etiology for childhood leukemia and CNS tumors.[38] However, Smith et al. did not demonstrate polyomavirus sequences in samples derived from leukemic cells with amplifiable DNA.[39] There is not any consensus on the laboratory strategies to screen BKV infection in susceptible population. Presence of Decoy cells in the urine of patients has been suggested as a sensitive tool to demonstrate overt BKV nephropathy.[1] Conversely, PCR has been assumed with higher sensitivity for detecting asymptomatic viruria and distinguishing BK viruria from JC viruria.[40] Tracking BK virus infection is possible by serial measurement of BK virus DNA in urine and blood using quantitative PCR method.[41] Urinary excretion of JC virus and BKV has been also reported in 19% and 7% of healthy asymptomatic population, respectively.[42] Regarding the high rate of BKV seropositivity in population, we used conventional PCR method to detect asymptomatic viruria. Choosing newly diagnosed patients helped the authors to diminish the possibility of acquired drug-induced immunodeficiency. Irrespective of showing urinary BKV excretion, no additive sign or symptom demonstrating BKV nephropathy was determined. Confirming BKV nephropathy (disease) needs serial evaluation of BKV-DNA in blood and urine samples predominantly by real-time PCR. In our study, 3 out of 31 patients with newly diagnosed ALL had BK viruria. We did not show BK viruria in the control group. Nonetheless, there was not any significant difference between BK viruria in ALL children and the control group. The result did not support the possible hypothesis that BKV activation may have a role in inducing ALL. However, large sample size of newly diagnosed ALL is recommended to evaluate the possible role of BKV in this group of patients. Furthermore, there was not any correlation between relapses and viruria. Long-term follow-up is needed to assess whether evolving BK viruria increases the chance of recurrent relapses. The rate of CNS relapse in our study was a bit higher compared to those reported by Pullen et al. and Pui et al. in their studies (12.7% vs. 7.7% and 5.9% in poor outcome group).[43,44] The shortage of newly diagnosed children with ALL because of low incidence of the disease was the limitation of our study.

CONCLUSION

BK viruria is not uncommon in children with newly diagnosed ALL. Although the incidence of BK viruria in ALL children is not significantly higher than normal population, proving the role of BKV in increasing the relapse rate of ALL needs longer cohort studies.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Randhawa P, Ramos E. BK viral nephropathy: an overview. Transplant Rev. 2007;21:77–85. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gasparovic ML, Gee GV, Atwood WJ. JC virus minor capsid proteins Vp2 and Vp3 are essential for virus propagation. J Virol. 2006;80:10858–61. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01298-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akan I, Sariyer IK, Biffi R, Palermo V, Woolridge S, White MK, et al. Human polyomavirus JCV late leader peptide region contains important regulatory elements. Virology. 2006;349:66–78. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shishidohara Y, Ichinose S, Higuchi K, Hara Y, Yasui K. Major and minor capsid proteins of human polyomavirus JC cooperatively accumulate to nuclear domain10 for assembly into virions. J Virol. 2004;78:9890–903. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.18.9890-9903.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flower AJ, Banatvala JE, Chrystie IL. BK antibody and virus-specific IgM responses in renal transplant recipients, patients with, malignant disease and healthy people. Br Med J. 1977;2:220–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6081.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noss G. Human polyoma virus type BK infection and T antibody response in renal transplant recipients. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg. 1987;266:567–74. doi: 10.1016/s0176-6724(87)80239-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamilton RS, Gravell M, Major EO. Comparison of antibody titers determined by hemaglutination inhibition and enzyme immunoassay for JC virus and BK virus. J Clin Microbial. 2000;38:105–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.105-109.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stolt A, Sasnauskas K, Koskela P, Lehtinen M, Dillner J. Seroepidemiology of the human polyomaviruses. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:1499–504. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18842-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirsch HH, Brennan DC, Drachenberg CB, Ginevri F, Gordon J, Limaye AP, et al. Polyomavirus- associated nephropathy in renal transplantation: Interdisciplinary analyses and recommendations. Transplantation. 2005;79:1277–86. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000156165.83160.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brennan DC, Agha I, Bohl DL. Incidence of BK with tacrolimus versus cyclosporine and impact of preemptive immunosuppression reduction. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:582–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bressollette-Bodin C, Coste-Burel M, Hourmant M, Sebille V, Andre-Garnier E, Imbert-Marcille BM. A prospective longitudinal study of BK virus infection in 104 renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1926–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vilchez AR, Madden RC, Kozinetz CA, Halvorson SJ, White ZS, Jorgensen JL, et al. Association between simian virus 40 and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet. 2002;359:817–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07950-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruce E, Reid MM, Craft AW, Gardner PS on behalf of the Newcastle Leukemia Research Group. Multiple virus isolation in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Infect. 1979;1:243–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borisch B, Caioni M, Hurwitz N, Dommann-Scherrer C, Odermatt B, Waelti E, et al. Epstein-Barr virus subtype distribution in angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy. Int J Cancer. 1993;55:748–52. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910550509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arthur RR, Dagostin S, Shah KV. Detection of BK virus and JC virus in urine and brain tissue by the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1174–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.6.1174-1179.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imperiale MJ. The human polyomaviruses, BKV and JCV: Molecular pathogenesis of acute disease and potential role in cancer. Virology. 2000;267:1–7. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imperiale MJ. Oncogenic transformation by the human polyomaviruses. Oncogene. 2001;20:7917–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tognon M, Corallini A, Martini F, Negrini M, Barbanti-Brodano G. Oncogenic transformation by BK virus and association with human tumors. Oncogene. 2003;22:5192–200. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chatterjee M, Weyandt TB, Frisque RJ. Identification of archetype and rearranged forms of BK virus in leukocytes from healthy individuals. J Med Virol. 2000;60:353–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doerries K. Human polyomavirus JC and BK persistent infection. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;577:102–16. doi: 10.1007/0-387-32957-9_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martini F, Iaccheri L, Martinelli M, Martinello R, Grandi E, Mollica G, et al. Papilloma and polyoma DNA tumor virus sequences in female genital tumors. Cancer Invest. 2004;22:697–705. doi: 10.1081/cnv-200032937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corallini A, Tognon M, Negrini M, Barbanti-Brodano G. Evidence for BK Virus as a Human Tumor Virus. In: Khalili K, Stoner GL, editors. Human Polyomaviruses: Molecular and Clinical Perspectives. New York: Wiley-Liss, Inc; 2001. pp. 431–60. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang M, Abend JR, Johnson SF, Imperiale MJ. The role of polyomaviruses in human disease. Virology. 2009;384:266–73. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maginnisa SM, Atwooda JW. JCV: An Oncogenic Virus in Animals and Humans? Semin Cancer Biol. 2009;19:261–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin PY, Fung CY, Chang FP, Huang WS, Chen WC, Wang JY, et al. Prevalence and genotype identification of human JC virus in colon cancer in Taiwan. J Med Virol. 2008;80:1828–34. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murai Y, Zheng HC, Abdel Aziz HO, Mei H, Kutsuna T, Nakanishi Y, et al. High JC virus load in gastric cancer and adjacent non-cancerous mucosa. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:25–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin SK, Li MS, Fuerst F, Hotchkiss E, Meyer R, Kim T, et al. Oncogenic T-antigen of JC virus is present frequently in human gastric cancers. Cancer. 2006;107:481–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boldorini R, Pagani E, Car PG, Omodeo-Zorini E, Borghi E, Tarantini L, et al. Molecular characterisation of JC virus strains detected in human brain tumours. Pathology. 2003;35:248–53. doi: 10.1080/0031302031000123245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delbue S, Pegani E, Guerini FR, Agliardi C, Mancuso R, Borghi E, et al. Distribution, characterization and significance of polyomavirus genomic sequences in tumors of the brain and its covering. J Med Virol. 2005;77:447–54. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiramizu B, Hu N, Frisque RJ, Nerurkar VR. High prevalence of human polyomavirus JC VP1 gene sequences in pediatric malignancies. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2007;53:4–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng H, Abdel Aziz HO, Nakanishi Y, Masuda S, Saito H, Tsunemaya K, et al. Oncogenic role of JC virus in lung cancer. J Pathol. 2007;212:306–15. doi: 10.1002/path.2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chessels JM, Veys P, Kempski H, Henley P, Leiper A, Webb D, et al. Long-term follow up of relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Br J Haematol. 2003;123:396–405. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nguyen K, Devidas M, Cheng SC, La M, Raetz EA, Carroll WL, et al. Factors influencing survival after relapse from acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Children's Oncology Group Study. Leukemia. 2008;22:2142–50. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greaves MF. Speculations on the cause of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 1988;2:120–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jourdan Da-Silva N, Perel Y, Mechinaud F, Plouvier E, Gandemer V, Lutz P, et al. Infectious diseases in the first year of life, perinatal characteristics and childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:139–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abend RJ, Jiang M, Imperiale JM. BK virus and human cancer: Innocent until proven guilty. Semin Cancer Biol. 2009;19:252–60. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang M, Entezami P, Gamez M, Stamminger T, Imperiale MJ. Functional reorganization of promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies during BK virus infection. MBio. 2011;2:e00281–10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00281-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mc Nally RJ, Eden TO, Alexander FE, Kelsey AM, Birch JM. Is there a common etiology for certain childhood malignancies? Results of cross-space-time clustering analyses. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2911–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith SA, Strickler HD, Granovsky M, Reaman G, Linet M, Daniel R, et al. Investigation of leukemic cells from children with common acute lymphoblastic leukemia for genomic sequences of the primate polyomaviruses JC virus, BK virus, and simian virus 40. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;33:441–3. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199911)33:5<441::aid-mpo1>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Randhawa P, Vats A, Shapiro A. Monitoring for polyomavirus BK and JC in urine: a comparison of quantitative polymerase chain reaction with urine cytology. Transplantation. 2005;79:984–6. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000157573.90090.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bechert JC, Schnadig JV, Payne AD, Dong J. Monitoring of BK Viral Load in Renal Allograft Recipients by Real-Time PCR Assays. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;133:242–50. doi: 10.1309/AJCP63VDFCKCRUUL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Egli A, Infanti L, Dumoulin A, Buser A, Samaridis J, Stebler C, et al. Prevalence of polyomavirus BK and JC infection and replication in 400 healthy blood donors. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:837–46. doi: 10.1086/597126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pullen J, Boyett J, Shuster J, Crist W, Land V, Frankel L, et al. Extended triple intrathecal chemotherapy trial for prevention of CNS relapse in good-risk and poor-risk patients with B-progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A Pediatric Oncology Group study. JCO. 1993;11:839–49. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.5.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pui CH, Boyett JM, Rivera GK, Hancock ML, Sandlund JT, Ribeiro RC, et al. Long-term results of Total Therapy studies 11, 12, 13A, 13B and 14 for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia at St Jude Children's Research Hospital. Leukemia. 2010;24:371–82. [Google Scholar]