Abstract

Cell surface G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) drive numerous signaling pathways involved in the regulation of a broad range of physiologic processes. Today, they represent the largest target for modern drugs development with potential application in all clinical fields. Recently, the concept of “ligand-directed trafficking” has led to a conceptual revolution in pharmacological theory, thus opening new avenues for drug discovery. Accordingly, GPCRs do not function as simple on-off switch but rather as filters capable of selecting activation of specific signals and thus generating textured responses to ligands, a phenomenon often referred to as ligand-biased signaling. Also, one challenging task today remains optimization of pharmacological assays with increased sensitivity so to better appreciate the inherent texture of ligand responses. However, considering that a single receptor has pleiotropic signalling properties and that each signal can crosstalk at different levels, biased activity remains thus difficult to evaluate. One strategy to overcome these limitations would be examining the initial steps following receptor activation. Even if some G protein-independent functions have been recently described, heterotrimeric G protein activation remains a general hallmark for all GPCRs families and the first cellular event subsequent to agonist binding to the receptor. Herein, we review the different methodologies classically used or recently developed to monitor G protein activation and discuss them in the context of G protein biased -ligands.

Keywords: Animals; Drug Discovery; methods; Heterotrimeric GTP-Binding Proteins; metabolism; Humans; Ligands; Receptor Cross-Talk; Receptors, G-Protein-Coupled; agonists; metabolism; Signal Transduction

Keywords: GPCRs, G protein, biased agonist, ligand-directed trafficking, ligand efficacy, G protein sensors, signaling pathways

1. INTRODUCTION

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent the largest family of transmembrane receptors and are virtually involved in the regulation of all physiological processes. They represent therefore a primary target for modern drugs development with potential application in all clinical fields. It has been estimated that some 30–50% of clinically available drugs target the function of GPCR family members [1–3]. These receptors propagate highly diverse extracellular signals into the cell interior by interacting with a broad range of intracellular proteins [4]. However, coupling with αβγ-trimeric G proteins remains the common hallmark of all GPCR family members and these proteins constitute one of the earliest plasma membrane transducers, relaying information from the cell surface receptor to others intracellular signaling molecules. Recently, GPCRs were found not to work linearly as simple on/off switches, triggering the full signaling machinery downstream the receptor, but rather as filters capable of activating a subset of specific effectors and fine tuning cellular responses and associated physiological responses. This concept, known as “ligand-directed trafficking” or “biased-agonism”, emphasizes that receptors are capable of generating textured responses to ligands [5]. On the other hand, the efficacy of ligands acting on GPCRs may be different depending upon the cellular effector considered [6, 7]. In keeping with these different concepts, it follows that the choice of cellular effectors to measure receptor activation is crucial and that different signaling pathways should be considered in order to appreciate the real texture of ligand effects. However, pleiotropic and crosstalk signaling between GPCRs makes functional selectivity of ligands difficult to decode. One alternative to bypass this problem might be to look at the initial step following agonist binding to receptors at the level of the plasma membrane: i.e. G protein activation. This review will focus on the heterotrimeric G proteins with a specific emphasis on the different tools available to evaluate receptor-mediated G protein activation.

2. HETEROTRIMERICG PROTEINS STRUCTURE

The discovery of heterotrimeric G proteins relaying information from receptors inserted in plasma membrane to intracellular effectors revolutionized our view of how ligands functions. Alfred G. Gilman and Martin Rodbell were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1994, “for their discovery of G-proteins and the role of these proteins in signal transduction in cells” [8, 9].

G proteins are heterotrimeric proteins consisting of Gα, Gβ and Gγ subunits tightly associated and bound to the inner face of the cell plasma membrane (Fig.(1)), where they predominantly relay receptor activation. To date, 16 different Gα subunit encoding genes, 5 Gβ subunit genes and 12 Gγ subunit genes have been described in humans [10]. Additional variants can be generated by alternative splicing and post-translational processing, leading to up to 23 different Gα subunits isoforms. Even if theoretically more than one thousand of distinct heterotrimers may exist, it has been shown that all combinations may not be relevant in signal transduction [11]. Moreover, the nature of the heterotrimer depends on the cell type[12].

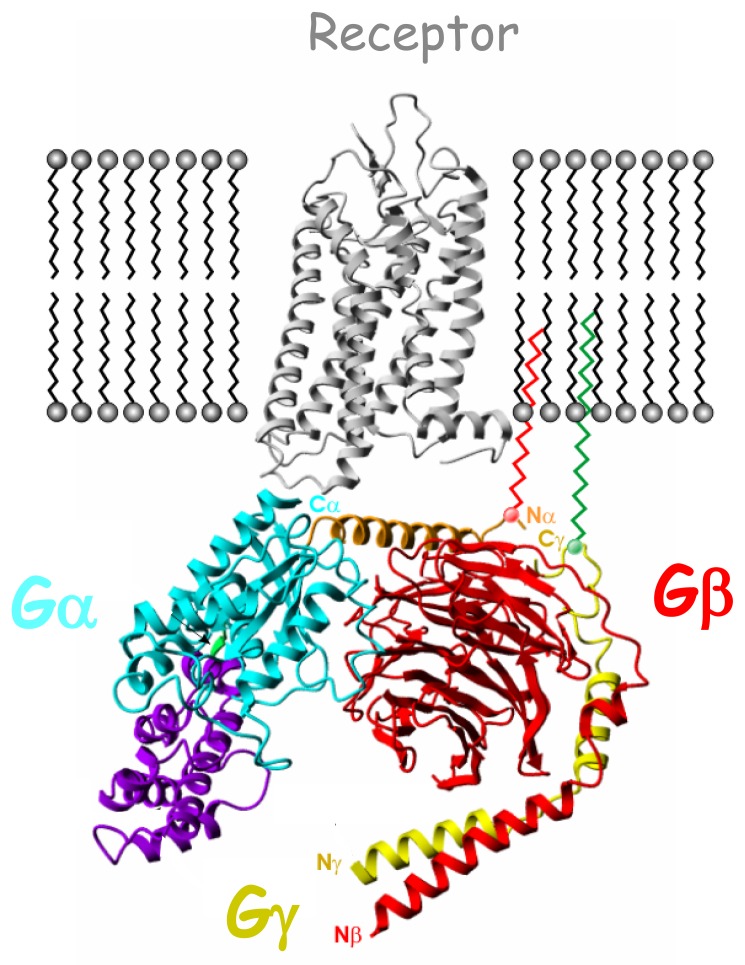

Fig. 1.

Schematic complex in the plasma membrane between rhodopsin (gray; PDB code 1GZM) and the inactive heterotrimeric G protein composed of αi1, β1, and γ2 subunits (light blue/violet, red and yellow respectively; PDB code 1GG2). Gαi1 N-terminal helix (αN) is shown in brown, while Gαi1-GTPase and Gαi1-helical domains (αi1H) are in light blue and violet respectively. Linker 1 connecting Gαi1-GTPase to the Gαi1H is represented in green. Both Gαi1N and Gγ2 C-terminal helix (γ2C) are anchored to the membrane through lipid modification.

The Gα subunit (Fig. (1)) is composed of an intrinsic GTPase domain involved in GTP binding and hydrolysis but also in interactions with Gβγ subunits, receptor and effectors [13]. This domain is characterized by three flexible loops identified as switches I, II and III and regulates G protein activation through very subtle conformational rearrangements. The α subunit exhibits an additional helical domain connected to the GTPase domain by the flexible linker 1 acting as a lid over the nucleotide binding pocket [14, 15]. All Gα subunits (except Gαt) are palmitoylated and/or myristoylated at their N-terminus allowing anchor age to the plasma membrane.

The Gβ subunit (Fig. (1)) shows a peculiar beta-propeller structure with seven WD-40 repeats. The N-termini of Gγ and Gβ subunits make extensive contacts through a coiled coil interaction all along the base of Gβ. Therefore, Gβ and Gγ subunits are tightly associated and may be separated only under denaturating conditions. Examination of crystal structures of different heterotrimers revealed two sites of interaction between Gα and Gβγ, involving switches I and II and the amino-terminal helix of Gα [16, 17]. Gγ subunits exhibit farnesylation or geranylgeranylation modifications cooperating in trans with Gα acylation to allow proper targeting of Gαβγ trimers from the endoplasmic reticulum to the plasma membrane [18]. As Gβ subunits lack lipid modifications, Gγsubunits act as chaperones for Gβ targeting to the plasma membrane.

Several receptor regions contact surfaces of all three subunits [13, 19] (Fig. (1)). Both N- and C-terminal regions of Gα subunits have been implicated in receptor interaction. However, the C-terminus plays a crucial interaction point since derived peptides can directly compete for the coupling of the G protein with the receptor (See section 6.1). Gβγ subunits enhance receptor-Gα interaction but can also directly interact with the receptor through their C-terminal regions. The receptor regions involved in these interactions localized to the intracellular loops and the C-terminal tail. Basic amino acids sequences in both the N-terminal and C-terminal part of the third intracellular loop appear particularly important. The C-terminal tail of the receptor also determines important interactions with Gβ subunit. It is of note that today, we still do not understand the molecular basis for the selectivity of G protein coupling to the receptor.

3. THE HETEROTRIMERIC G PROTEIN ACTIVATION CYCLE

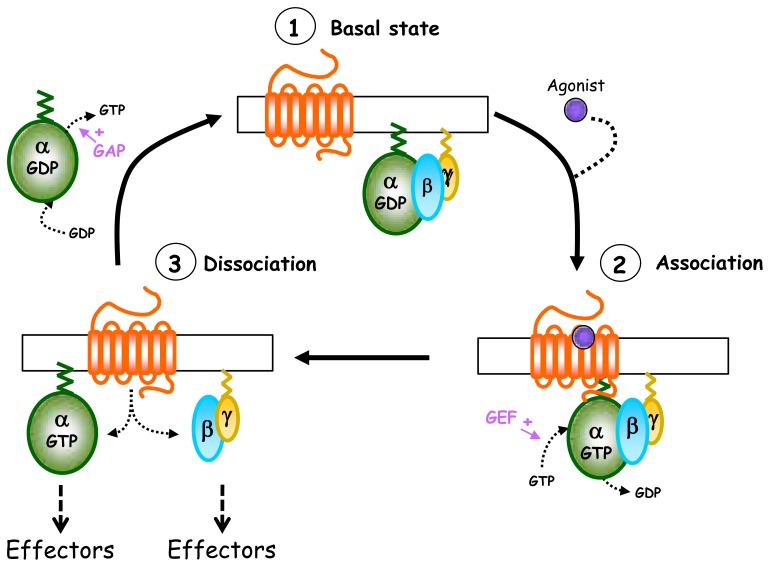

According to classical dogma, the heterotrimeric G protein activation cycle operates as follows (Fig. (2)). In the absence of receptor stimulation, Gα and Gβγ remain associated in a GDP-bound, inactive form physically dissociated from the receptor. Agonist binding to the receptor initiates conformational changes allowing coupling with Gαβγ. This interaction initiates G protein activation which then enters the “GTPase cycle” [8, 17, 20]. The activated receptor acts as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF), promoting a conformational change in Gα and ensuing GDP release. GTP, in much higher concentrations than GDP in the cytosol, then binds to Gα, switching its conformation to the active state. In the traditional view of heterotrimeric G protein activation, GDP/GTP exchange drives the dissociation of Gα from Gβγ and the receptor (“collision model”). However, recently, several groups have suggested a new model where nucleotide exchange only promotes structural rearrangements within preformed receptor-G protein complexes (“conformational model”) [21, 22]. The dissociated Gα-GTP and Gβγ can activate different effectors and signaling cascades (ion channels, enzymes…). Termination of the signal is facilitated by the inherent GTPase catalytic activity of Gα which hydrolyses GTP to GDP, and allows reassociation of Gα with Gβγ. Then, the G protein initiates a new cycle. To date, although we distinguish different Gαsubunits isoforms functionally, they all share a similar mechanism of activation.

Fig. 2.

Heterotrimeric G protein activation cycle. In the absence of agonist (1, basal state), GαGDP-βγ heterotrimeric G protein forms a tight inactive complex dissociated from the receptor. The activation of the receptor by the agonist promotes recruitment of Gαβγ to the receptor and the subsequent GDP/GTP exchange at the level of the Gα subunit (2, association). This nucleotide exchange then leads to the dissociation of the receptor and also of the Gα-GTP and Gβγ subunits, which are now able to activate their effectors (3, dissociation). The activation cycle is terminated by the Gα intrinsic GTPase activity which allows GTP hydrolysis and the reassociation of Gα-GDP with Gβγ subunits so to restore the inactive basal state (1).

GDP/GTP exchange and GTP hydrolysis represent two limiting steps in the G protein activation cycle. They are tightly regulated by accessory proteins which accelerate or impede these events by modulating kinetic constants and differ according to the Gα isoform. These numerous regulatory proteins were reviewed by Sato et al. [23]and may act as:

GEFs (guanine nucleotide exchange factors), such as AGS1, Ric-8, GAP-43 for example. These regulators interact with Gα, likely in a subtype-specific manner, and stimulate the exchange of GDP for GTP to accelerate the generation of the active form.

GDIs (guanosine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors), such as AGS3, AGS4, AGS5, RGS12, RGS14. In contrast to GEFs, GDIs stabilize Gα in an inactive GDP-bound conformation. Most of these proteins possess a 19–30 amino acids conserved motif named GPR (G protein regulatory) or GoLoco (“Gαi/o-Loco” interaction) motif which specifically interacts with Gαi/o subunits and is directly involved in prevention of GDP dissociation but also in Gα-Gβγ reassociation. In fact, these proteins exhibit dual functions: they may hinder signaling through Gαi/o by stabilizing the GDP-bound conformation, but they may also sustain Gβγ-dependent activation by inhibition of Gβγ association with GDP-Gα[24].

GAPs (GTPase-activating proteins) which antagonize GEFs activity and accelerate GTP hydrolysis back to GDP, thus favoring the G protein resting state and termination of G protein signaling. They act allosterically to stabilize the transition state occurring during GTP hydrolysis and promote reassociation of Gα and Gβγ. Some G protein–regulated effectors can also exhibit GAP activity such as phospholipase C-β activated by Gq and p115RhoGEF activated by Gα13. Among GAPs, RGSs (regulators of G protein signaling) represent the largest family with more than 20 members identified so far [25].

4. DIFFERENT CLASSES OF HETEROTRIMERIC G PROTEINS FOR ACTIVATION OF DIFFERENT EFFECTORS

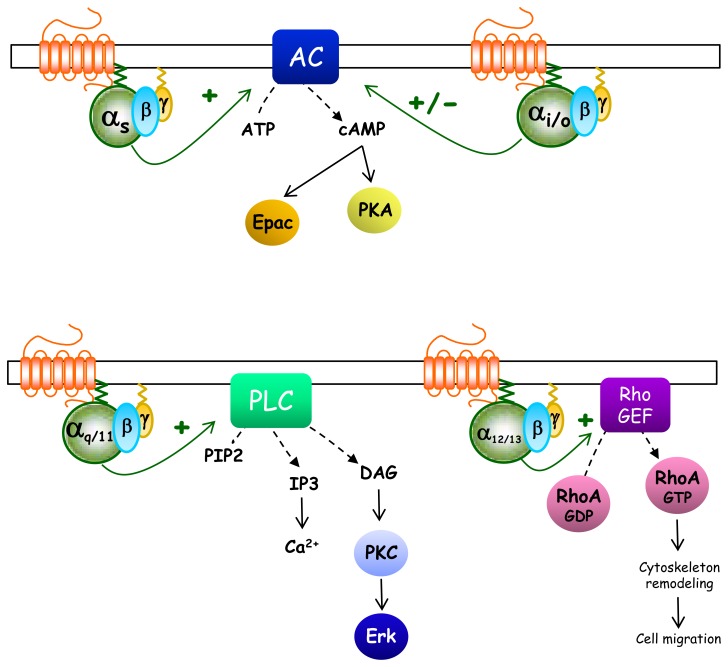

G proteins are classified into four families, based on t he homology of the primary sequence of the Gα subunit and to some extent, the selectivity of effectors activation (reviewed in [26, 27]) (Fig.(3)).

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of heterotrimeric G protein canonical pathways. Gαs-coupled receptors usually promote direct activation of adenylyl cyclase (AC) leading to intracellular cAMP production which can directly bind and activate Protein Kinase A (PKA) or Exchange Protein directly Activated by cAMP (Epac) effectors. On the contrary, Gαi/o-coupled receptors counteract the actions of Gs-GPCRs and inhibit AC activity even if they can also activate it through Gβγ subunits. The main effector of Gαq/11-coupled receptors is phospholipase C which catalyzes the cleavage of membrane-bound phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate (PIP2) into the second messengers inositol (1,4,5) triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). IP3 acts on IP3 receptors found in the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to elicit Ca2+ release from the ER, while DAG diffuses along the plasma membrane where it may activate membrane localized forms of Protein Kinase C (PKC). The effectors of the Gα12/13 pathway are RhoGEFs which, when bound to Gα12/13 allosterically, activate the cytosolic small GTPase, Rho. Then, active Rho-GTP can activate various proteins responsible for cytoskeleton regulation.

The Gαs family is composed of four isoforms, produced by alternative splicing, with a ubiquitous distribution, and Gαolf which has a more restricted expression in olfactory neurons. These G proteins directly stimulate transmembrane adenylyl cyclases (AC) leading to the production of cAMP. These proteins were also shown to stimulate GTPase activity of tubulin and Src tyrosine kinase. They are substrate for ADP-ribosylation mediated by cholera toxin responsible for inhibition of GTPase activity and the permanent activation of Gαs.

The Gαi/o family comprises the ubiquitous Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3 but also GαoA and GαoB which are predominantly expressed by neurons and neuroendocrine cells. Also included in this group and with restricted distribution, are Gαz which can be found in platelets and neurons, Gαt1 and Gαt2 expressed in retina and Gαgust in taste buds. They all inhibit adenylyl cyclase activity and decrease intracellular cAMP levels. Beyond AC, most of the isoforms can also activate K+ channels or inhibit Ca2+channels. All these subunits can be ADP-ribosylated and inactivated by pertussis toxin.

The Gαq/11 family, including Gαq, Gα11, Gα14, Gα15 and Gα16 isoforms, stimulates membrane-bound phospholipase C-β, which hydrolyses phosphatidyl 4,5-diphosphate (PIP2) into two second messengers, inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). IP3 is responsible for Ca2+ liberation from intracellular stores, while DAG activates protein kinase C. Others effectors are also cited in the literature as, for example, p63-RhoGEF and K+channels.

The Gα12/13 family comprises only 2 members to date (Gα12 and Gα13) with a ubiquitous expression profile. They regulate Rho family GTPase signaling through RhoGEF activation and control cell cytoskeletal remodeling, thus regulating key biological processes such as cell migration. They can also activate a large panel of different effectors such as radixin, A-kinase anchoring proteins, phospholipases D, protein phosphatase 5.

Gβγ complexes, initially thought to only favor Gα anchorage to the plasma membrane and to stabilize the inactive state of Gα, are now known to mediate many functional responses on their own following GPCRs activation (reviewed in[12]). Many effectors can be activated by interaction with Gβγ subunits such as K+ channels (GIRK 1,2,4), phospholipases C-β, adenylyl cyclase (II,IV,VII), Src kinases, while others will be inhibited such as, adenylyl cyclase I, Ca2+ channels (N, P/Q, R types). The Gβγ dimer composition seems to be essential in dictating the specificity of both receptors and the effectors for their coupling to the G protein [10]. Although Gβγ is always depicted as an inseparable dimer, several works have suggested the existence of Gβ or Gγ monomer activity (reviewed in[10]) and recently it was demonstrated that Gβ can activate K. lactis pheromone pathway in the absence of the Gγ subunit[28].

5. INDIRECT ASSAYS TO ASSESS RECEPTOR-MEDIATED G PROTEIN ACTIVATION

GPCRs ligands are usually classified according to their receptor specificity and intrinsic activity. Originally, this classification was essentially based on the effect of ligands on the activity of only the primary effector pathway, usually involving second messenger generation, which is generally assigned to the receptor of interest. According to their relative efficacy compared with the physiological agonist, ligands were identified as partial or full agonists when able to induce a fraction or a full response respectively, whereas neutral antagonists were believed to be devoid of effect and inverse agonists allow the inhibition of constitutive activity.

5.1. Gs-Gi activation

Both Gs and Gi proteins predominantly act by activating or inhibiting adenylyl cyclase respectively and thus regulating intracellular ATP conversion into cAMP (Fig. (3)). The direct measurement of adenylyl cyclase activity is possible using [α-32P] ATP as the enzyme substrate [29]. However, most investigators usually determine intracellular cAMP levels. The intracellular cAMP concentration is regulated by the balance between production rate by adenylyl cyclases and degradation rate by phosphodiesterases. Historically, cAMP was the first second messenger quantified in living cells and its measure has been widely used to test ligands acting on Gs- and Gi-coupled receptors. The early development of cAMP antibodies [30] allowed the development of Radioimmunoassays (RIA), Enzyme Immunoassays (EIA), Chemiluminescent Immunoassays (CLIA) and more recently Homogeneous Time Resolved Fluorescence (HTRF) assay, motivated by the desire to move away from the use of radioactivity. These methods are now very sensitive (detection of less than one femtomole) and adapted to a homogenous format allowing their use in the context of ligand screening in pharmaceutical industry. However, they cannot follow kinetics of cAMP levels fluctuations in living cells as they consist essentially of static measurements after cell lysis and based on the accumulation of cAMP in the presence of a phosphodiesterase blocker so to increase cAMP levels and enhance detection sensitivity. Another disadvantage of current cAMP assays to assess ligand efficacy may be the global cAMP levels evaluation of the cell since cAMP signal was shown to be compartmentalized within the cell and local responses may thus be diluted in the general background [31]. During the last few years, fluorescent-based sensors evaluating spatiotemporal resolution of cAMP signals in living cells have been extensively developed [32]. All of these approaches rely on the use of genetically encoded fluorescent reporters using cAMP binding properties of cAMP downstream effectors, protein kinase A (PKA) and Epac (exchange proteins directly activated by cAMP). After cell transfection of the biosensor, accurate monitoring and visualizing of the cAMP dynamics in the different cell compartments is possible by measuring FRET (fluorescence resonance energy transfer). Sensing of cAMP can rely on conformational changes of the biosensor when the reporter is solely based on the use of the cAMP binding domain of the effector as for the Epac-based biosensor [33] or on the behavior of the entire effector as for protein kinase A sensor measuring dissociation of its regulatory and catalytic subunits which occurs after cAMP binding [34]. Similar strategies were applied using BRET-based biosensors [35] based on the use of luminescence probes which offer better sensitivity and wide dynamic range of detection. Such probes are suitable tools for screening of new ligands for GPCRs. However, despite their high sensitivity, all these techniques remain indirect readouts of the G protein activation since their focus on the evaluation of cAMP downstream signaling. More recently, Pantel et al. described a more direct cAMP detection system using a genetically modified luciferase whose activity is restricted to the cAMP binding domain of RIIβB subunit of the PKA (pGloSensor™, Promega) [36]. When coexpressed with the melanocortin-4 receptor, this cAMP-luciferase probe demonstrated very high sensitivity allowing detection of inverse agonist activity of ligands in the absence of PDE inhibitor. Despite promise, this latter method requires use of stably transfected cells for high efficiency as it was poorly reproducible intransient transfected cells (unpublished data from our lab). Another recent technology for direct cAMP detection using luminescence as a read-out and based on enzyme fragment complementation technology (Discoverex, CA) offers great utility and sensitivity for a large panel of both Gs- and Gi-coupled GPCRs with large range dynamics for inhibitory signals (unpublished data from our lab).

Another specific difficulty to evaluate ligand efficacy at the level of cAMP signal emanates from Gi-coupled receptors. In this case, adenylyl cyclase must be obligatorily pre-stimulated, generally using forskolin, to increase cAMP concentration in order to detect the inhibition of the enzyme in a second step. Despite wide use, this strategy is at risk of biased interpretations since forskolin and Gαs bind different adenylyl cyclase regions and therefore induce different conformations of the enzyme catalytic core [37]. In fibroblast cells overexpressing PTX-insensitive Gαi/o proteins, Ghahremani et al. have shown that the dopamine Gi-coupled D2S receptor may inhibit the activity of AC through distinct Gαi proteins [38]. In fact, when adenylyl cyclase is stimulated with forskolin, D2S-induced inhibition of the enzyme is mediated by Gαi2, while following activation by PGE1, the receptor inhibits AC through Gαi3. This suggests that Gαi2 and Gαi3 demonstrate specificity for different conformational states of adenylyl cyclase. Furthermore, differences may also arise from activation specificities among adenyl cyclase isoforms. It was shown that forskolin preferentially activates ACI over ACII, ACV, or ACVI, while Gαs stiumlates ACII more efficiently than ACI, ACV, or ACVI [39]. Today, evaluating ligand efficacy at Gi-coupled receptors still remains a challenging task and especially for the detection of weak efficacies, as available cAMP assays provide generally too low dynamic ranges of inhibition detection. To resolve this specific problem to Gi/o-mediated cAMP signals, chimeric G proteins were developed. Basically, this strategy relies on the conversion of the Gi/o into another signaling unit which still relies on the Gi/o activation mode. Generally, conversion is based on the production of another second messenger easy to measure such as Ca2+ or inositol phosphates. In this context, the first chimeric G protein was designed by substituting three amino acids of Gαq by the corresponding residues of Gαi2 [40]. This Gαq-i2 was functionally expressed and induced PLC activation (Gαq effector) through the stimulation of Gi-coupled receptors, demonstrating that the chimera keeps G i specificity [40]. Due to its ability to associate with multiple receptors without high selectivity [41], Gα16 was then thought to be the optimal G protein backbone for the generation of G protein chimera to obtain a truly universal G protein adaptor stimulated by all the GPCRs. However, several Gi-linked receptors and also some Gs-linked receptors are unable to activate PLC via Gα16. To optimize the Gα16 so to enlarge its binding capacity to a maximum of receptors, different chimeras were constructed by incorporating variable length of Gαz (Gi/o family) or Gαs sequences into the C terminus of Gα16and were highly efficient to mediate both Gi and Gs dependent-G16 signaling [42, 43]. Finally, further analysis revealed that the Gα16-z chimera is able to transmit signal from virtually all G protein-linked receptors (Gi-, Gs- and the Gq) [44]. Another chimera has been generated based on the mutation of a critical amino acid located in the linker region connecting the GTPase and the helical domain of the Gαq protein. Hence, the mutant acquires the capacity to transmit Gi- and Gs- linked GPCR signals [45]. Further additional mutations in the C-terminus of Gαq combined with the linker mutation led to an optimized “universal” G protein chimera now functional for all the three G protein families [46]. Even if these artificial chimeras are far from the reality of natural G proteins, they remain very attractive tools to screen for ligands at GPCRs especially for orphan GPCRs [47, 48], at least at first instance.

5.2. Gq activation

To test ligands efficacy on Gq/11-coupled receptors, different assays have been developed to measure inositol phosphate or calcium concentrations as reflects of PLC activity (Fig. (3)). Original methodologies for determination of PLC activity used artificial phospholipid vesicles containing [3H]-inositol PIP2 and enzyme activity was measured by following the amount of [3H]-inositol triphosphate (IP3) released into the aqueous solution [49]. This technique was improved by Mullinax et al. who developed labeled phospholipids bound on microplates [50]. However, this technique is only suitable for cell extracts or permeabilized cells. More classically used for the investigation of Gq/11-coupled receptors is the monitoring of inositol phosphate derivative production. The radiolabelled precursor, [3H]myo–inositol, is incorporated into intact cells as [3H]-phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Upon agonist binding to the receptor, PI4,5P2 are hydrolyzed by PLC into [3H]-IP3 and DAG. LiCl must be added to prevent dephosphorylation of IP3 and to increase sensitivity. The mass of soluble IP3 is a quantitative readout of receptor activation. [3H]-IP3 is quantified following purification on anion-exchange chromatography or by HPLC [51, 52]. HPLC also allows quantification of the production of the other inositol phosphates [53]. As for cAMP, specific IP3 antibodies allowed development of several specific and sensitive immunoassays. Other assays using IP3 binding proteins competition can also be used and were proposed for high-throughput screening of GPCR ligands [54]. However, IP3 production is very transient due to its extremely short half life making it difficult to accurately quantify. By comparison, IP1, a downstream metabolite of IP3, is stable in the presence of LiCl providing a better read out of Gq-coupled receptors. Thus, IP1-based immunoassays have been developed and offer both high sensitivity and assay window. This sensitive technique already allowed the detection of inverse agonist activity at mGlu5 receptor [55] and is readily adaptable to high-throughput screening assays to screen for ligands efficacy.

A common alternative to explore ligand efficacy at Gq-coupled-receptor is the evaluation of calcium mobilization. In response to PLC activation, IP3 produced in the cytoplasm, binds to endoplasmic reticulum IP3 receptors thus liberating calcium from internal stores. Specific dyes generating fluorescence upon binding of free Ca2+ have been developed since almost 30 years. Most of them derivate from calcium chelators EGTA or BAPTA fused with an additional acetoxymethylester (AM) group to allow cell penetration. Once in the cell, AM is cleaved by endogenous esterases and the intracellular probe then becomes active. A number of chemical calcium indicators are now available and the investigator must consider the Ca2+ affinity of the probe which must be compatible with the intracellular concentration of Ca2+ to measure. Spectral properties of the indicators can also differ, varying from single wavelength to ratiometric indicators. The different criteria to select the suitable probe were recently reviewed with advantages and limitations discussed for each probe [56]. These indicators are very powerful tools, easy to use and to calibrate, and suitable for cell imaging. However, they present some limitations to their use. First, they act per se as Ca2+ buffers and can therefore influence Ca2+ levels and kinetics and, second, their cellular localization cannot be controlled or targeted. The other alternative is the use of genetically encoded luminescent proteins. Aequorin was the first Ca2+-sensitive photoprotein isolated from the jellyfish Aequorea Victoria [57]. In the presence of Ca2+, the photoprotein undergoes a conformational change allowing oxidation of its substrate coelenterazine into coelenteramide. Upon relaxation, this product goes from an excited state to the ground state and emits a flash blue light (469 nm). The great advantage of aequorin is that it can be targeted to several intracellular cell compartments (nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi apparatus, mitochondrial matrix, mitochondrial intermembrane space, plasma membrane) by direct fusion of specific targeting sequences, thus offering the possibility of subcellular Ca2+ measurements. Generally, Gq-coupled receptors mediated Ca2+ signals are often monitored using mitochondrial-aequorin, because ER has close physical relationship with mitochondria and the release of Ca2+ from ER exposes mitochondria to very high Ca2+ concentrations [58]. However, when compared with fluorescent dyes, this approach, which necessites a transfection step, is not easy to calibrate and not sensitive enough for cell imaging since one molecule of aequorin will produce only a single photon. To overcome some of these limitations, others Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent proteins have been developed, such as the cameleon conformational FRET sensors. These biosensors were initially based on tandem repeats of mutants fluorescent proteins (Blue or Cyan mutant GFP and Green or Yellow mutant GFP) used as FRET donors and acceptors, interconnected by a Ca2+-sensitive linker of calmodulin fused to peptide M13 (a calmodulin binding peptide from myosin light-chain kinase). Upon Ca2+ binding, calmodulin forms a compact complex with the M13 domain and this intramolecular rearrangement modifies FRET between the fluorescent proteins [59]. These probes have been further improved and present now expanded dynamic range. Others FRET-based Ca2+ indicators, such as pericams and camgaroos, have also been developed (reviewed in [60]) and are amenable for high throughput screening in drug discovery [61].

5.3. G12/13 activation

The evaluation of G12/13 activation still remains problematic, essentially because we still have not identified their specific direct effectors as compared with the other G protein families. Since they were found to regulate actin cytoskeleton remodeling, G12/13 proteins have been essentially studied in the context of cell proliferation, migration and morphology where they have been shown to regulate many diverse effectors (Fig. (3)). Thus, given their biological action, they elicit the interest of a large number of research groups especially for the chemokine receptors for which they play major role in regulating chemotaxis process. However, quantitative measurement of G12/G13 activation remains a challenging task today. Usually, evaluation of G12/13 activation is based on measurement of downstream effectors. The common effector downstream of G12/13 activation appears to be the Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors (RhoGEFs), which can be visualized by immunoblotting techniques, with limited sensitivity for accurate evaluation of ligand efficacy [62, 63]. However, measuring RhoGEFs activation does not ensure G12/G13 activation readout since most of the G12/13-coupled receptors also couple to other G protein isoforms such as Gq/11 which can also converge on RhoGEF activation. Specific identification of G12/G13-dependent receptor signaling can be evaluated by siRNA knockdown strategy but it only remains qualitative. Thus, to date, G12/13 activation is not appropriate for evaluation of ligand efficacy.

All together, these strategies involving measurement of effector activity and/or second messenger production have been greatly improved during the last few years and are valuable for the study of the effects of GPCR ligands. However, they suffer from some general limitations. First, they are distal events following interaction of the ligand with the GPCR and may be subjected to amplification and compartmentalization which cannot always be readily appreciated. Second, most receptors generally simultaneously activate different G protein isoforms. Therefore, assessment of receptor activity at the level of second messenger increases the occurrence of cross -talks thus making evaluation of ligand efficacy complicated. That is, signaling becomes more complicated to analyze when one looks farther from the initiating event of receptor activation at the plasma membrane. One strategy to overcome these limitations would be examining the initial step of receptor activation common to all GPCR families which is the direct activation of heterotrimeric G proteins. Indeed, G proteins represent the only signaling relay common to all GPCRs and their activation is the first step consequent to receptor stimulation. For these reasons, an accurate method to depict the intrinsic activity of ligands would be to determine unequivocally their activation profile on different G protein isoforms. Several methods have been developed to evaluate G protein activation which are more or less adapted to accurate ligand efficacy assessment.

6. DIRECT ASSAYSTO ASSESS RECEPTOR-MEDIATED G PROTEIN ACTIVATION

6.1. General pharmacological tools

When available, pharmacological inhibitors targeting specific G protein families provide powerful tools to study the involvement of these proteins in GPCR signal transduction by preventing associated downstream signaling.

Pertussis toxin (PTX), formerly called Islet Activating Protein (IAP), isolated from Bordetella pertussis, catalyses ADP-ribosylation of all Gαi/o subunits which subsequently remain locked in their inactive state, thus unable to activate its effectors. This mechanism prevents Gi/o proteins from functionally interacting with GPCRs. PTX have been largely used to characterize involvement of Gi/o proteins in receptor signaling in many cellular models. Recently, the role of Gi/o protein was studied in vivo using transgenic mice expressing the PTX catalytic subunit specifically in pancreatic islet [64]. Mastoparan, a peptide toxin from wasp venom, can also interfere primarily with Gi/o proteins [65]. It promotes dissociation of GDP and accelerates GTP binding on Gαi/o subunits thus mimicking an agonist-bound receptor. A mastoparan derivative, mastoparan-S, was described to selectively activate Gαs [66]. Cholera toxin from Vibrio cholerae, targets specifically intracellular Gs proteins and induces their constitutive activation by permanent ADP-ribosylation[67]. The toxin was quite useful in the purification and characterization of Gs proteins [68]. The search for specific Gs inhibitors led to the identification of suramin, an anti-helminthic drug, and its derivatives that directly interact with G proteins and interfere with GTP binding on both Gs and Gi/o proteins [69]. Some suramin analogues, NF449 and NF503, appear to be specific for Gαs and to block the coupling of β-adrenergic receptors to Gs in S49 cyc - cells [70].

The Gq-dependent signaling pathway can also be modulated by recently discovered molecules: Pasteurella multocida toxin (PMT) and YM-254890. PMT is a bacterial toxin activating Gq/11 proteins, but the molecular mechanism underlying G protein activation is unknown [71]. However, PMT was also suggested to activate others signaling pathways such as G12/13 and Rho proteins [72, 73]. YM-254890, a cyclic depsipeptide isolated from culture of Chromobacterium sp. QS3666, appears as a potent and specific inhibitor of the Gq/11 family [74]. It prevents the GDP/GTP exchange reaction on Gαq, Gα11 and Gα14 isoforms by inhibiting the GDP release. Recent analysis of the X-ray crystal structure of the Gαqβγ–YM-254890 complex showed that YM-254890 binds specifically to the linker domain connecting the helical from the GTPase domain of Gαq, thus preventing flexibility during the Gα activation process [75]. More recently, Ayoub et al. have described another small molecule BIM-46187, as a non-specific and ubiquitous inhibitor of receptor-G protein signaling through selective binding to the Gα subunit [76]. This pan-inhibitor of GPCR signaling might be useful to dissect G protein -dependent and -independent signaling pathways.

An alternative approach for the identification of selective G protein-dependent pathways is the use of synthetic peptides mimicking the COOH-terminus of the different Gα subunits which compete with Gα subunit binding to the receptor and thus inhibit G protein dependant signaling. In fact, the COOH-terminal part of Gα subunits is critical for both the interaction with their cognate receptors and the specificity of each Gα isoform. These G protein inhibitors were first used in permeabilized cells where they were able to block the stimulation of adenylyl cyclase mediated by β-adrenergic receptors [77]. The technique was further extended with the generation of minigene plasmid vectors encoding the C-terminal peptide sequence of most Gα subunits facilitating their expression in living cells by transfection or infection [78]. However, since the peptides act as competitive inhibitors and thus must be expressed in the cell at high concentrations for high efficiency, one has to be cautious on the results interpretations as they will largely depend on the transfection/expression efficacy of the peptides [79]. Obviously, this will also vary between cell lines as they usually have different G proteins complements [80]. By opposition to chemical G protein inhibitors, which only allows discrimination between G protein families, this strategy further permits the dissection of G protein isoforms involved in receptor -mediating signaling.

Participation of specific G proteins in in vivo signal transduction has been extensively elucidated using G protein-deficient mouse models allowing classical or conditional inactivation of the genes encoding the different G protein subunits. Several knockout mice models lacking expression of one or two Gα subunits or Gβγ subunits have been generated and the consequences of the genetic disruption on physiology and physiopathology have been extensively reviewed [81]. Another similar strategy is the knockdown of Gα and Gβ subunits through small interfering RNA, adapted to in vitro studies [82]. Although these genetic strategies provide high specificity of inactivation between the different and closely related G protein subunits, they can be subject to compensatory mechanisms by modifications of the expression levels of other endogenous G proteins, thus interfering with the results interpretation.

Although all these methods are quite useful, they still remain qualitative in that they just help in the dissection of molecular mechanisms underlying G protein-dependent receptor signaling. However, they cannot replace direct measurement of the protein activity as a quantitative assessment of G protein activation.

6.2. [35S]GTPγS binding

The most common technique to directly measure G proteins activation following agonist stimulation is the [35S]GTPγS binding assay monitoring the nucleotide exchange process in membranes extracts, which was first described by Hilf et al. [83]. This radioactive GTP analog binds the Gα subunit following activation but resists GTPase hydrolysis, thus stabilizing the Gα in the active form and preventing G protein activation cycle arrest. Therefore, Gα-[35S]GTPγS subunits accumulate and radioactivity can be counted following filtration procedures to separate bound from free radioactivity. As [35S]GTPγS cannot cross plasma membranes, the assay is restricted to cell membrane preparations or permeabilized cells [84]. The method was also used in tissue sections and autoradiography allowing anatomical localization of activated G proteins [85]. The pharmacology of a large panel of GPCRs ligands has been largely investigated by the use of this method (reviewed in [86]), thus allowing accurate characterization of their G protein potency and efficacy. The [35S]GTPγS binding method provides a sensitive tool to characterize constitutive activity of receptors through identification of inverse agonists [87] but also to evaluate antagonist activity by the shift of agonist-induced dose-response curves (pA2 value determination). While it proves to be a powerful assay to evaluate Gi/o-coupled receptor activation, a major pitfall of this method comes from its low sensitivity to analyze receptors coupled to others G protein families, essentially due to a poor signal to background ratio. Indeed, PTX-sensitive G proteins generate optimal results most probably because of their generally higher expression levels in most mammalian cells and their greater nucleotide exchange rate. Even though suitable for the measurement of endogenous G protein activity, a large number of [35S]GTPγS experiments were performed in heterologous expression systems stably or transiently expressing receptor and/or different G protein subtypes of interest; however, competition with endogenously expressed G proteins may confuse the issue. Thus, cell lines expressing low levels of mammalian G protein such as Sf9 insect cells have also been used [88, 89]. In all cases, changing both the receptor and G protein stoichiometry may profoundly influence ligand pharmacology, for example, the relative potency of agonists as discussed by Kenakin in the light of the concept of ligand-selective receptor conformations [90]. This has led to the conception of receptor-Gα fusion proteins, forcing a 1:1 expression ratio, which will be discussed below. Beside potency modulation, G protein subtype overexpresssion may modify ligand efficacy at G proteins as well and thus reveal protean agonism of ligands as shown for α2A-adrenergic receptor[91].

Even if [35S]GTPγS binding accurately measures direct G protein activity, it cannot provide information about the subtypes specificity of the activated G protein and therefore has been further improved. Thus, the existence of selective antisera for the different Gα subunits allows immunocapture and thus enrichment of G proteins of interest following [35S]GTPγS binding[92, 93]. Immunoprecipitation of the G protein can also be coupled to scintillation proximity assays (SPA) to eliminate unbound radioactivity separation steps and may be applied to high-throughput screening [94, 95]. In this method, G protein immunoprecipitation is followed by a second immunoprecipitation of the radioactive G protein immuno-complex using specific beads containing scintillant and coated with a non specific anti-IgG. When [35S] is in close proximity to the scintillant, it generates a luminescent signal detected by a microplate scintillation counter. However, the problem of antibody specificity and immune-capture efficiency remains an impediment to these assays. Other modifications of the initial [35S]GTPγS assay use non-radioactive GTP analogs. Among them, Europium-labeled GTP appears to be an interesting alternative in HTRF-based detection assays [96, 97]. Fluorescent BODIPY® GTPγS analogs may also be used [98] but need further validation because of their non negligible hydrolysis rate by Gαi/o subunits [99].

The receptor-G protein (R-G) fusion strategy was developed during the 90’s to force a 1:1 stoichiometry efficient coupling of a given receptor to a specific G protein subunit [100] and has subsequently been applied to a large number of receptors [101–103]. This technique relies on the fusion of the Gα-protein subunit N-terminus to the receptor C-terminus in a single open reading frame, leading to the expression of a unique polypeptide containing both functionalities. G protein activation is then assessed according to [35S]GTPγS binding performed on cell membranes expressing the R-G fusion construct, allowing evaluation of the role of the G protein isoform on the potency/efficacy of different ligands. Using this technique, different β2-adrenergic agonists showed different pharmacological profiles (potency and efficacy) depending on the Gα-protein subunits fused to the β2-receptor [104]. This approach also proved useful in the context of protean agonism revealing for instance that one dopamine receptor ligand could behave as an agonist or an antagonist depending on the D2R-Gα-subunit pair considered [103]. Beyond G protein activity, the use of R-G fusions was an ingenious and well-adapted strategy to study G protein transactivation mechanisms mediated by GPCR dimers [105–107]. Also true for classical [35S]GTPγS binding assays using endogenous G proteins, the main drawback of the R-G fusion activation measurement is probably competition by endogenous receptors and/or G proteins which can result in a poor signal to noise ratio. To bypass this problem, Gαi/o PTX-resistant isoforms can be used, coupled with PTX pre-treatment of cells to neutralize endogenous Gαi/o isoforms [102]. However, this issue still persists for all other G protein families (G s, Gq/11, G12/13). Another concern is the non-dynamic measurement of R-G activity since the Gα subunit is irreversibly fused to the receptor and thus could give rise to artefactual interpretations. Finally, an additional problem comes from the fusion of the G protein to the C-terminus of the receptor by itself that can impair the proper trafficking of the receptor to the plasma membrane and/or its pharmacological properties (ligand binding/activation process). Also, an accurate characterization of the R-G fusion must precede its subsequent use.

6.3. Plasmon Waveguide Resonance

Plasmon waveguide resonance (PWR) spectroscopy is an optical approach derived from Surface Plasmon Resonance and developed by Salamon’s group to allow the study of membrane-associated proteins. There is abundant literature dealing with the physical principle of this technique [108, 109]. Briefly, a polarized continuous wave laser is used to excite the resonator which consists in a thin silver film coated by a thicker silica layer deposited onto the surface of a glass prism. Laser excitation generates an evanescent electromagnetic field localized at the outer surface of the silica. Resonance excitation generated depends on the angle of incidence of the laser beam and is modulated by molecules present at the outer surface. The protein of interest is inserted in a single lipid bilayer at the interface between the silica film of the resonator and an aqueous buffer compartment in which molecules can be added [109]. PWR allows real-time measurement of molecule or protein binding to a specific receptor inserted in the lipid bilayer with high sensitivity in the absence of radioactive or fluorescent label. This technique has been used to characterize kinetics and thermodynamics of conformational events associated with the binding of ligands and of G proteins on the δ-opioid receptor (DOR) and provided new insights into the function of these molecules [110]. These studies demonstrated that receptor-G protein interactions are quite selective depending both on the ligand-bound states of the receptor but also on the G protein isoforms [110]. Interestingly, by coupling PWR studies of receptor-G protein interaction with GTPγS binding assay examining the G protein activation state, a disconnection between the two events was demonstrated which highlights the existence of a non-active precoupled state of the receptor. Thus, PWR has been demonstrated as a powerful approach to measure selectivity and activity of GPCR ligands towards the different G protein isoforms. This was possible by the use and insertion of different purified G protein isoforms in reconstituted membrane systems containing the receptor and thus allows an acute control of the expression of each protein partners [111]. On the other hand, this method is limited because it is based on artificial cell system reconstitution which does not reproduce the real cellular environment, especially regulations by other cellular proteins which could participate and modify ligand-receptor-G protein relationships. Moreover, PWR requires receptor and G proteins purification steps, thus dramatically impairing its use for large -scale screens. Finally, this approach is hardly accessible to non-specialist researchers, as illustrated by the limited number of GPCR studied to date[110, 112–114].

6.4. “RETvolution”: monitoring real-time G protein activation in living cells

The field of cell biology has been subjected to a real shake-up with the introduction of non invasive biophysical RET-based approaches, allowing for the first time, quantification of intracellular signaling events dynamics in real-time and in living cells. The evaluation of receptor-mediated G protein activation did not escape from view using these technologies.

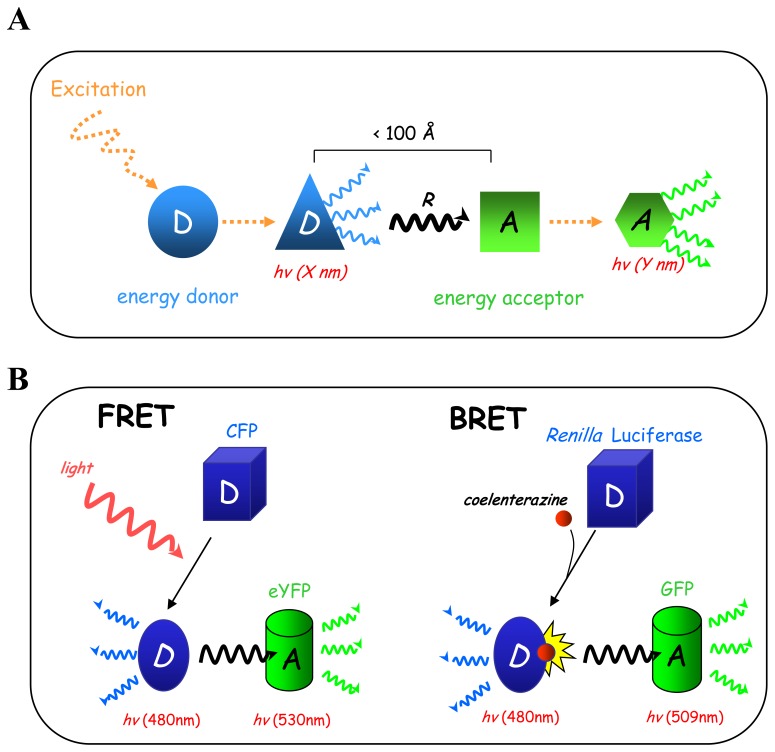

6.4.a. The RET principle

The Resonance Energy Transfer (RET) biophysical principle was discovered and published by Theodor Förster in 1940s [115], but its ultimate impact is still evolving. Basically, RET relies on non-radiative energy transfer between an energy donor and an acceptor molecule occurring under highly restrictive distance parameters (Fig. (4A)). When donor and acceptor are in close proximity (distance < 100 Å), the energy generated by donor excitation is then transferred to the acceptor through a non radiative process of resonance, which in turned becomes excited and emits at a different wavelength from that of the donor. Given its distance dependence, RET is highly suitable to monitor protein-protein interactions in living cells between two partners tagged with different RET partners following transfection. Interestingly, the efficiency of RET is inversely proportional to the sixth power of the distance between donor and acceptor dipoles, thus allowing accurate measurement of relatively small variations in distance or orientation between the two RET partners. Thus, RET is suitable not only to measure intermolecular events (protein-protein interactions) but also allows monitoring of intramolecular events like protein conformational changes. Another parameter limiting RET efficiency and fluctuating between energy donor/acceptor couples is the spectral overlap between the emission wavelength of the donor and the excitation wavelength of the acceptor, since acceptor excitation is only dependent on the donor emission. Depending on the nature of the energy donor, RET will be defined as: i/FRET (Fluorescent Resonance Energy Transfer) when using a fluorescent donor and excited by an external energy source (laser or arc lamp), or ii/BRET (Bioluminescent Resonance Energy Transfer) when using an enzymatic donor (Renilla luciferase) and excited by oxidation of its coelenterazine substrate (Fig. (4B)). Both FRET and BRET use a fluorescent energy acceptor. Because of its fluorescent nature, FRET allows subcellular localization of RET events. However, on the other end, extrinsic donor excitation by a light source has several limitations due to direct excitation of the fluorophore acceptor or photobleaching of the FRET partners and, in the cell context, cell autofluorescence [116]. In this context, BRET is a better choice because of the enzyme-dependent activation of the donor, thus allowing a better signal to noise ratio[116].

Fig. 4.

Resonance Energy transfer (RET). (A) RET is a non radiative energy transfer which occurs between an energy donor and an energy acceptor over a restricted distance. When the energy donor is excited and is in close proximity (< 100 Å) to the donor, the energy released is then transferred by resonance (R) to the energy acceptor, which in turns becomes excited and emits at a different wavelength to that of the donor. (B) Depending on the nature of the energy donor we distinguish two RET: i/FRET (Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer) with a fluorescent energy donor excited by external light and ii/BRET (Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer) using an enzymatic energy donor (Renilla Luciferase) excited by degradation of its substrate (coelenterazine).

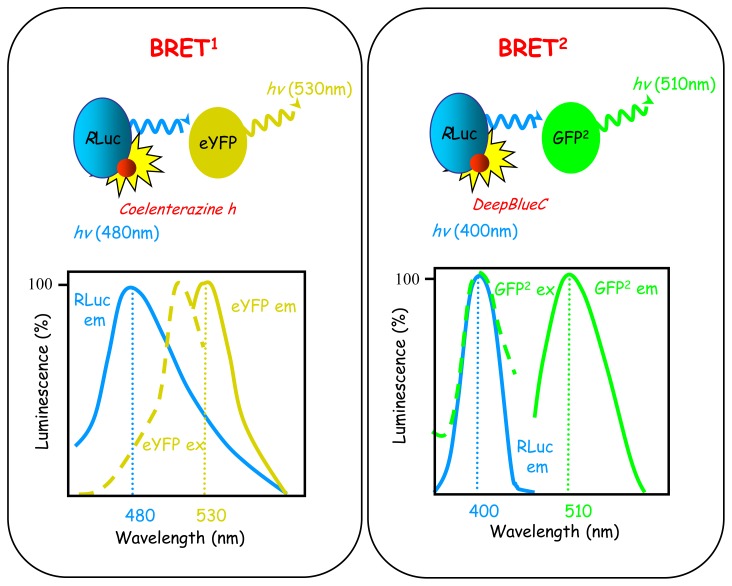

Originally, BRET-based approaches used two BRET generations called BRET1 and BRET2 based on the use of different luciferases, coelenterazine substrates and fluorescent acceptors conferring specific and distinct spectral properties of the energy donor/acceptor couple [117, 118] (Fig. (5)). At that time, most of the studies in biology favoured BRET1-based approaches over BRET2, essentially because of the low luminescence intensity emission of the BRET2 luciferase, requiring higher expression level of the proteins fused to the different BRET partners. Nevertheless, BRET1 provides much lower sensitivity due to the considerable overlap between acceptor and donor emission spectra, compared with BRET2, for which separation between the two spectra is optimum (Fig. (5)). It follows that BRET1 generates higher background compared with BRET2 and is not optimal for detection of weak RET signals (which can be true especially in the detection of subtle conformational changes) for which BRET2 seems more suitable. Exactly same problem also applies to FRET and none of the available donor/acceptor couples offers optimum spectrum resolution. Until recently, BRET1-based approaches did not justify their continued use as major improvements of BRET2 luminescence intensity were introduced with the use of a Renilla luciferase mutant (Rluc8), demonstrating equal or even higher luminescence intensity compared with BRET1 [119]. Rluc8-BRET2 is so sensitive that it can be even used for microscopic detection of BRET in living cells but also in living animals [120]. The main limiting aspects of the use of BRET or FRET approaches are the necessity to transfect cells for introduction of RET-tagged proteins, and the molecular weight of the protein fused to the proteins of interest (27–36 kDa). Thus, it remains essential to control for the biological properties (cell localization, functionality) of the fusion proteins before subsequent RET experiments.

Fig. 5.

The basics of BRET1 and BRET2. BRET1 and BRET2 are based on the use of different coelenterazine substrates (Coelenterazine h for BRET1 and DeepBlueC in BRET2) which confer specific spectral properties to Renilla luciferase. The energy acceptor is then adapted to the emission wavelength of Renilla luciferase in each cases (eYFP in BRET 1and GFP10 in BRET 2).

6.4.b. Sensing G protein activation using RET

In the traditional view of heterotrimeric protein activation (see section 2), the active receptor initiates sequential events based on multiple protein-protein interactions and/or conformational changes: i/receptor-GαGDP-βγ protein interaction, ii/Gα-GDP/GTP exchange, iii/receptor-G protein dissociation and Gα-Gβγ dissociation, iv/Gα-GTP hydrolysis, v/Gα-GDP and Gβγ reassociation. Thus, this biological process obviously provided an ideal template for RET-based assays development. During the last ten years, several groups have developed different RET-based probes to monitor real -time dynamics of receptor mediated-G protein activation cycle in living cells.

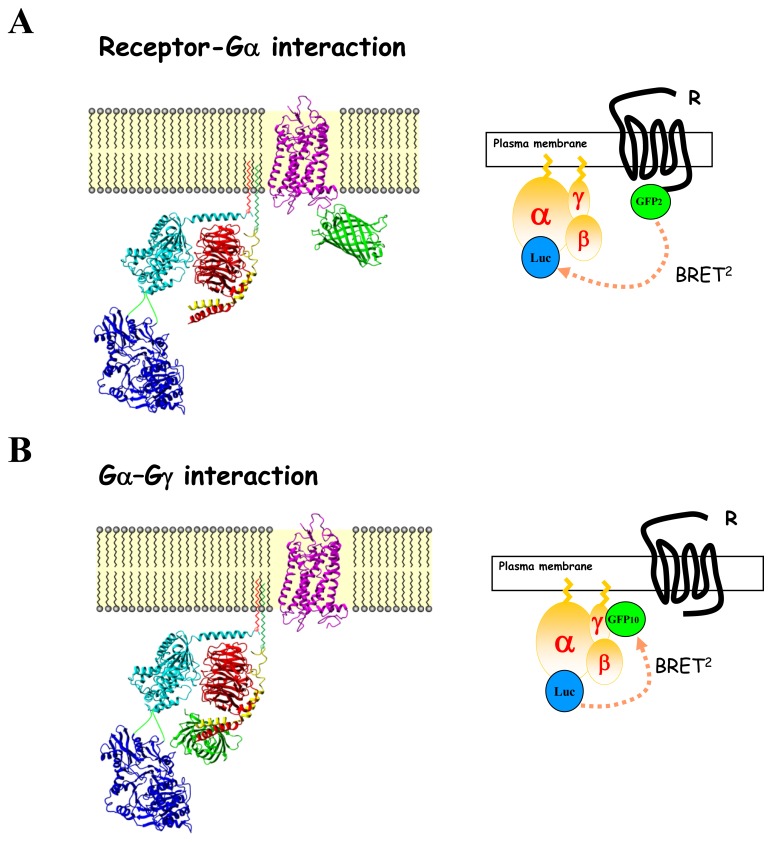

Indirect measurement of G protein activation: receptor-G protein interactions

G protein activation can be assessed indirectly by RET by monitoring interactions in real time between receptors and G proteins subunits in living cells (Fig. (6A)). For this purpose, BRET or FRET donors and acceptors are fused on the C-terminus of the receptor and in one of the different subunits of the Gαβγ protein and the RET -fusion proteins are then overexpressed in mammalian cells. BRET or FRET were measured between receptor and Gβ or G γ subunits tagged at their N-terminus with the BRET partner and further between the receptor and Gα subunit [121–124]. Generating Gα-BRET probes was not an easy task given the complex structure of the protein compared to Gβ or Gγ subunits and the relative high size of the BRET partner (around 26–40 Kda) to insert. Actually, several probes were generated based on the Gα crystal structures available (unpublished data), but only a few potential insertion sites did not disrupt trafficking and functional properties of the Gα subunit. In fact, all studies used intramolecular Gα-BRET probes with the RET partner generally introduced in the helical domain of the protein or the linker region connected the helical from the GTPase domain. Although FRET assays failed to detect basal interactions between receptor and G protein subunits[122], by opposition several BRET-based studies clearly monitored constitutive R-G complexes, thus highlighting the existence of preformed R-G complexes [21, 121, 123, 125, 126]. Lack of FRET sensitivity over BRET (see RET principle) may probably account for these discrepancies. In all studies, agonist stimulation of the receptor promoted a rapid (milliseconds) modification of the RET signal between several GPCRs and either Gs or Gi/o proteins. Interestingly, depending on the insertion site of the RET partners within the G protein subunit, agonist-stimulation can induce either an increase or a decrease in RET, thus demonstrating that the RET in fact monitors conformational rearrangements within preformed R-G complexes (or occurring during the receptor-G protein interaction step). This notion is supported by a study where three different BRET probes within the Gαi1 subunit were used to monitor its interaction with the α2A-adrenergic receptor [21]. Similar results were obtained when measuring the interaction between G protein subunits and the δ-opioid receptor [123]. Receptor-G protein RET-biosensors monitoring conformational rearrangements occurring during the activation process are highly prone to pharmacological characterization of ligands. Two comparable studies performed on β2-adrenergic and α2A-adrenergic receptors demonstrated that agonist stimulation promoted a concentration-dependent increase in RET between receptor and Gγ2 in good agreement with second messenger responses [121, 122]. Partial agonist led to a partial BRET modulation compared to the maximal RET signals obtained in the presence of full agonists, while antagonists completely blocked the agonist response. Moreover, RET monitoring of agonist-induced receptor-Gγ conformation changes shows high selectivity for the coexpressed Gα isoforms, despite all G protein subunits being overexpressed (which could favour unspecific coupling), thus demonstrating the intrinsic coupling selectivity of each receptor [121, 125]. Indeed, agonist-induced BRET increase between the Gs/Gi coupled β2-adrenergic receptor and Gγ2 was only detected in presence of Gαs and Gαi but not with Gαq or Gα11 [121] while a FRET increase between the Gi-coupled protease-activated receptor and Gβγ was only detected in the presence of Gαi but not Gαs [125]. Gα-specificity of RET changes detected between receptor and Gβγ subunits was also confirmed for Gi-coupled-receptors by specific blockage with pertussis toxin pre-treatment [121]. Finally, RET analysis of receptor-mediated G protein activation allowed measurement of the real time kinetics of the activation process, on a milli-second time scale following immediate agonist stimulation [21, 121, 122, 125]. Although RET-based assays monitoring R-G interactions may provide accurate information about the G protein activation process, it remains an indirect sensor which monitors conformational rearrangements occurring within preformed R-G complexes. It follows that RET-based R-G monitoring does not necessarily corroborate G protein activation state. For instance, the α2-adrenergic antagonist RX821002 increases the BRET signal between Gαi1 and α2A-adrenegric receptor but is unable to promote Gαi1 activation [21]. The capability of the R-G BRET assay to probe ligand-induced structural rearrangements in preexisting receptor-G protein complexes and leading to changes in the distance between the receptor carboxyl tail and the G protein subunits has profound impact in the field of biased agonists. Actually, if different ligands promote distinct R -G conformational changes through a unique receptor, this could highly suggest that they engage different signaling outputs. Similar approaches allowed characterization of ligand-biased MAPK signaling through the β1-adrenergic receptor[124].

Fig. 6.

Configurations of the different BRET assays used to probe receptor-mediated G protein activation. Schematic representation of a GPCR (purple, Rhodopsin PDB code 1L9H) and a heterotrimeric G protein composed of αi1, β1, and γ2 subunits (light blue, red and yellow respectively; PDB code 1GG2) interacting at the plasma membrane, fused to luciferase (blue; PBD code 1LC1) or to GFP (green; PDB code 1GFL) as indicated. (A) BRET monitoring receptor-Gα interaction. (B) BRET monitoring Gα/Gγ interaction.

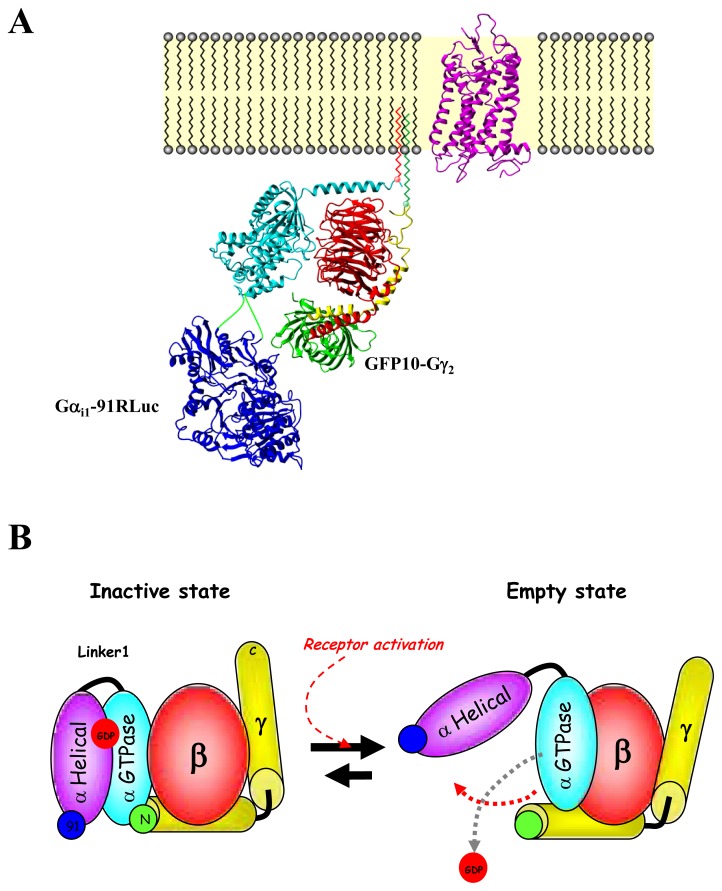

Direct measurement of G protein activation: G protein subunits interactions

According to the classical model of heterotrimeric protein activation, receptor-mediated Gα-GDP/GTP exchange triggers the dissociation of the Gα-GTP from the Gβγ dimer and the receptor. Obviously, measuring RET between Gα and Gβγ subunits was identified as the easiest way to directly measure G protein activation (Fig. (6B)). The first studies measuring FRET between Gα and Gβγ subunits were carried out in Dictyostelium discoideum and yeast and demonstrated good correlations between agonist-mediated BRET modulation and G protein activation [127]. Numerous other studies then used FRET or BRET strategies to follow the heterotrimeric G protein activation cycle by measuring Gα and Gβγ in mammalian cells [21, 22, 122, 123, 128–132]. In all cases, agonist-promoted decreases in RET between Gα and Gβγ have been interpreted as evidence of receptor-promoted dissociation of the G protein complex. Although loss of RET is consistent with dissociation, it can also reflect conformational rearrangements that promote an increase in the distance between the two RET partners. Consistent with this latter hypothesis, and as observed for receptor-G protein subunits interactions, the use of RET probes at different positions within the Gαβγ complex could lead to either an increase or a decrease in RET signals[21, 133]. It follows that when assessing the G protein activation using RET-based methods, the position of the RET partners in the G protein complex appears to be crucial especially for ligand efficacy evaluation. The insertion of the Rluc at different positions in the Gαi1 highlighted that insertion after amino acid 91 within the helical domain (Gαi1-91Rluc) led to a potent and unique direct sensor of G protein activation when measuring its interaction with the energy acceptor GFP10 tagged-Gγ2 subunit at its N-terminus (GFP10-Gγ2) [21] (Fig. (7A)). This Gαi1-91Rluc/GFP10-Gγ2 BRET2 probe allowed measurement of the greater separation between the Gα helical domain and the Gγ2 N-terminus occurring during GDP/GTP exchange that is translated by the BRET sensor as a decrease in BRET following receptor activation (Fig. (7B)). Indeed, BRET modulations measured in the presence of various α2A-adrenergic ligands correlated perfectly with their intrinsic signaling efficacy. Agonists induced a potent BRET decrease, partial agonists induced only a fraction of the signal promoted by full agonist while antagonists had no effect. No other probe position used to detect changes within the Gαβγ complex provided such a direct correlation between signaling efficacy and BRET changes [21]. Thus, the Gαi1-91 Rluc/GFP10-Gγ2 BRET2 probe proved to be a potent sensor to monitor the separation of the Gα helical domain and the Gγ N-terminus occurring during G protein activation and thus to evaluate receptor ligands efficacy.

Fig. 7.

Gα-91Rluc/GFP10-Gγ BRET probe is a direct sensor of G protein activation. (A) Localization of the BRET probes (Rluc and GFP10) within Gαi1β1γ2 G protein. (B) Schematic representation of structural rearrangement within Gαi1β1γ2 depicted by BRET following receptor activation. Rluc probes within Gαi1 are shown in blue while GFP probe at the C-terminal of Gγ2 is shown in green. The scheme represents an opening of Gαi1-GTPase and Gαi1H through linker 1 (like a clamp), thus increasing RLuc91-Gγ2N and RLuc122-Gγ2N distance. These rearrangements would thus create an exit route for the guanine nucleotide and thus measure directly the activation state of the G protein.

RET monitoring receptor-G protein or G protein subunit interactions represents a quite promising approach in the future to dissect GPCRs ligand efficacies most proximal to the receptor. Even if this strategy has only been described for a few Gα RET probes, it could be easily enlarged to all the other Gα subunits for all G proteins family and could thus help unravel potential ligand-biased activity at specific sets of G protein subunits that remains elusive. Another benefit of RET-based assays over other assays is the acute temporal appreciation of signaling events, allowing detection of ligand selectivity at the level of kinetics. Commonly, ligand selectivity is quite apparent in concentration-response curves; however, differences between agonists can only be detectable by kinetics analysis as already reported for β-arrestin translocation [134]. Finally, RET-based assays offer the possibility to visualize spatial organization of the signaling and so to dissect biased activity of ligands in terms of signal compartmentalization.

7. G PROTEIN ACTIVATION AND BIASED AGONISM

Originally, GPCRs were thought to function necessarily through rapid activation of heterotrimeric G proteins, thus propagating the different intracellular signaling pathways. In the last few years, it seems that GPCRs could activate distinct G protein-dependent and -independent transduction pathways and that GPCR ligands, namely biased-ligands, can selectively favour activation of only a subset of the pathways activated by a given receptor. Although GPCRs can modulate a large variety of distinct signaling pathways, classification of biased-ligands was restricted to two groups depending on their ability to activate two main transduction pathways [135]: i/ G protein-biased ligands which promote G protein activation without β-arrestin recruitment and ii/ β-arrestin-biased ligands which recruit β-arrestin to the receptor and initiate consecutive signaling pathways in the absence of G protein activation.

Interestingly, very few ligands have been yet identified as perfect G protein-biased ligands, namely inducing G protein signal transduction without any β-arrestin recruitment [135–137]. For instance, GMME1 ligand binding to the CCR2 receptor led to calcium mobilization, caspase-3 activation and consecutive cell death, but did not recruit beta-arrestin2 [138]. Indeed, most of the ligands classified as G protein-biased are less potent for β-arrestin recruitment than for G protein activation but they do activate the β-arrestin pathway [134, 135, 139]. Interestingly, some ligands are biased in regard to the different G protein families [140, 141]. Thus, atosibans electively activates the Gi pathway after binding to the Gq/i-coupled oxytocin receptor without any Gq-mediated signal transduction and very little receptor desensitization, thereby leading to the selective inhibition of cell growth [140]. In opposition to G protein biased activity, the vast majority of biased ligands identified so far exhibits exclusive β-arrestin activity for a number of receptors [135, 142], including the AT1 angiotensin II receptor [143], β1-[144] and β2-adrenergic receptors [145], or the CXCR7 decoy receptor[146].

Most of biased ligand screening has focused on evaluation of G protein and β-arrestin pathways separately. Many sensitive assays are available to measure different levels of the β-arrestin pathway activation in living cells [147], including β-arrestin translocation assays evaluating β-arrestin recruitment to the receptor [148–151], or measures of different conformational changes of the β-arrestin protein occurring during its activation process [152, 153], to confocal analysis of the spatial redistribution of the receptor/β-arrestin complex [143, 154–156]. On the contrary, direct and accurate evaluation of G protein activation still remains elusive as discussed above. The monitoring of G protein activity in the context of “biased activity” is generally based on the evaluation of its downstream signaling by measuring G protein effectors activation (phosphorylation or second messengers measurement) or by direct evaluation of the G protein activity using the low sensitive assay [35S]GTPγS binding, which is the most classical method to directly analyse G protein activation but exhibits a poor signal to noise ratio, even with technical improvements, and is not sensitive enough to monitor activity of all G protein families [48, 157]. Given the general low efficacy of biased ligands, [35S]GTPγS binding assay cannot be adapted to evaluate G protein biased activity. The difficulty to measure G protein biased-activity comes also from the existence of a large panel of Gαβγ protein subunits combinations compared to the existence of only two β-arrestin (β-arrestin1 and β-arrestin2) that are almost impossible to evaluate individually. Recent development of RET-based probes monitoring the activation of specific Gαβγ combinations should certainly help in that direction. This raises the question whether β-arrestin biased ligands are truly unable to activate G proteins or if the assays were simply not sensitive enough to detect low levels of G protein activation. Taking into account that biased ligands are generally less potent than full agonists [123, 158, 159], the low-sensitivity of current assays monitoring G protein activation appears to be a limiting step in the global appreciation of G protein biased-ligands. It is interesting to note that most of the work describing β-arrestin-selective signaling never evaluated potential involvement of the G protein component in this pathway, essentially as they failed to primarily identify G protein activity using classical direct assays (which does not mean there is not). Indeed, this could be easily performed by blunting G protein expression and/or activity using siRNA strategy or toxin/chemical inhibitors as mentioned above. β-arrestin siRNA strategies were often used to evaluate implication of this protein in a signaling pathway.

Thus, evaluation of biased activity is not an easy task given the high diversity of GPCRs signaling and the molecular crosstalk which can occur between the different signaling pathways. Restricting evaluation to the G protein and the β-arrestin components appears exclude the full array of signaling pathways linked to a given receptor and their interconnections. G protein and β-arrestin are good examples as, originally, these two proteins were tightly connected given the canonical role of β-arrestin in dampening G protein signaling during desensitization [160] but they also demonstrate independent signaling as shown by the selective G protein or β-arrestin biased activity of ligands. Another difficulty comes from the insufficient sensitivity of the different assays to evaluate activity of the different signaling components which will depend on the ligand efficacy. This highlights the necessity to accurately monitor the various signal transduction pathways in order not to underestimate ligand efficacy. One possibility is to multiplex different assays to evaluate activation of specific effectors. This is currently being done to evaluate β-arrestin-dependant pathways but is still missing for G protein signaling, for which only one assay is generally performed. However, even with accurate β-arrestin and G protein assays, multiplexing assays which will examine different vantage points in the signalosome, from the initial signaling event of receptor/G protein activation at the plasma membrane to the more downstream signaling events inside the cell, will probably be the best way to fully characterize the efficacy of a given ligand completely.

References

- 1.Hopkins AL, Groom CR. The druggable genome. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:727–30. doi: 10.1038/nrd892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vassilatis DK, Hohmann JG, Zeng H, Li F, Ranchalis JE, Mortrud MT, et al. The G protein-coupled receptor repertoires of human and mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4903–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0230374100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacoby E, Bouhelal R, Gerspacher M, Seuwen K. The 7 TM G-protein-coupled receptor target family. ChemMedChem. 2006;1:761–82. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ritter SL, Hall RA. Fine-tuning of GPCR activity by receptor-interacting proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:819–30. doi: 10.1038/nrm2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenakin T. Agonist-receptor efficacy. II. Agonist trafficking of receptor signals. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1995;16:232–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)89032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kenakin T. Functional selectivity through protean and biased agonism: who steers the ship? Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1393–401. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.040352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galandrin S, Oligny-Longpre G, Bouvier M. The evasive nature of drug efficacy: implications for drug discovery. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:423–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilman AG. G proteins: transducers of receptor-generated signals. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:615–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodbell M. The role of hormone receptors and GTP-regulatory proteins in membrane transduction. Nature. 1980;284:17–22. doi: 10.1038/284017a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McIntire WE. Structural determinants involved in the formation and activation of G protein betagamma dimers. Neurosignals. 2009;17:82–99. doi: 10.1159/000186692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hynes TR, Mervine SM, Yost EA, Sabo JL, Berlot CH. Live cell imaging of Gs and the beta2-adrenergic receptor demonstrates that both alphas and beta1gamma7 internalize upon stimulation and exhibit similar trafficking patterns that differ from that of the beta2-adrenergic receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44101–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405151200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dupre DJ, Robitaille M, Rebois RV, Hebert TE. The role of Gbetagamma subunits in the organization, assembly, and function of GPCR signaling complexes. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;49:31–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-061008-103038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oldham WM, Hamm HE. Heterotrimeric G protein activation by G-protein-coupled receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:60–71. doi: 10.1038/nrm2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iiri T, Farfel Z, Bourne HR. G-protein diseases furnish a model for the turn-on switch. Nature. 1998;394:35–8. doi: 10.1038/27831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamm HE. The many faces of G protein signaling. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:669–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wall MA, Coleman DE, Lee E, Iniguez-Lluhi JA, Posner BA, Gilman AG, et al. The structure of the G protein heterotrimer Gi alpha 1 beta 1 gamma 2. Cell. 1995;83:1047–58. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambright DG, Sondek J, Bohm A, Skiba NP, Hamm HE, Sigler PB. The 2. 0 A crystal structure of a heterotrimeric G protein. Nature. 1996;379:311–9. doi: 10.1038/379311a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michaelson D, Ahearn I, Bergo M, Young S, Philips M. Membrane trafficking of heterotrimeric G proteins via the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3294–302. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bourne HR. How receptors talk to trimeric G proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:134–42. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bourne HR, Sanders DA, McCormick F. The GTPase superfamily: conserved structure and molecular mechanism. Nature. 1991;349:117–27. doi: 10.1038/349117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gales C, Van Durm JJ, Schaak S, Pontier S, Percherancier Y, Audet M, et al. Probing the activation-promoted structural rearrangements in preassembled receptor-G protein complexes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:778–86. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bunemann M, Frank M, Lohse MJ. Gi protein activation in intact cells involves subunit rearrangement rather than dissociation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:16077–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536719100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato M, Blumer JB, Simon V, Lanier SM. Accessory proteins for G proteins: partners in signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;46:151–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siderovski DP, Willard FS. The GAPs, GEFs, and GDIs of heterotrimeric G-protein alpha subunits. Int J Biol Sci. 2005;1:51–66. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross EM, Wilkie TM. GTPase-activating proteins for heterotrimeric G proteins: regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) and RGS-like proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:795–827. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cabrera-Vera TM, Vanhauwe J, Thomas TO, Medkova M, Preininger A, Mazzoni MR, et al. Insights into G protein structure, function, and regulation. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:765–81. doi: 10.1210/er.2000-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milligan G, Kostenis E. Heterotrimeric G-proteins: a short history. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147 (Suppl 1):S46–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Navarro-Olmos R, Kawasaki L, Dominguez-Ramirez L, Ongay-Larios L, Perez-Molina R, Coria R. The beta subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein triggers the Kluyveromyces lactis pheromone response pathway in the absence of the gamma subunit. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:489–98. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-06-0472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]