Abstract

A comprehensive review of uniparental systems in South Amerindians was undertaken. Variability in the Y-chromosome haplogroups were assessed in 68 populations and 1,814 individuals whereas that of Y-STR markers was assessed in 29 populations and 590 subjects. Variability in the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroup was examined in 108 populations and 6,697 persons, and sequencing studies used either the complete mtDNA genome or the highly variable segments 1 and 2. The diversity of the markers made it difficult to establish a general picture of Y-chromosome variability in the populations studied. However, haplogroup Q1a3a* was almost always the most prevalent whereas Q1a3* occurred equally in all regions, which suggested its prevalence among the early colonizers. The STR allele frequencies were used to derive a possible ancient Native American Q-clade chromosome haplotype and five of six STR loci showed significant geographic variation. Geographic and linguistic factors moderately influenced the mtDNA distributions (6% and 7%, respectively) and mtDNA haplogroups A and D correlated positively and negatively, respectively, with latitude. The data analyzed here provide rich material for understanding the biological history of South Amerindians and can serve as a basis for comparative studies involving other types of data, such as cultural data.

Keywords: genetics, language and geography, mitochondrial DNA, Native Americans, South Amerindians, Y-chromosome

Introduction

Native Americans have been the subject of a large number of population genetic studies because of particular characteristics: (a) there are groups among them that until recently had a hunter-gatherer way of living with only incipient agriculture, typical of our ancestors, (b) they show considerable interpopulation but low intrapopulation variability, and (c) since until recently they could not write there is no written record of their history, except for those of non-Amerindian colonizers. Biological studies can therefore be used to investigate their past.

The first genetic studies examined the variability in blood groups and proteins and have been summarized in Salzano and Callegari-Jacques (1988) and Crawford (1998). The advent of modern molecular biology, which allows direct, detailed DNA analysis, has opened new possibilities for investigating these populations.

DNA studies can basically be divided into two groups: those involving autosomal markers and those involving uniparental (Y-chromosome, mitochondrial DNA) markers. The latter are important because they can provide a clear-cut pattern of historical events that is not clouded by recombination factors. For Amerindians, the number of reviews that have dealt with these markers is not large or comprehensive. For the Y-chromosome, Bortolini et al. (2003) considered 438 individuals from 23 Southern and one Northern Amerindian populations who were screened for eight single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and six short tandem repeat/microsatellite (STR) loci, and Zegura et al. (2004) studied 63 binary polymorphisms and 10 STR regions in 2,344 persons from 15 Northern and three Southern Amerindian groups. Only a few recent studies have used all known SNPs necessary to identify the major Native American Y-haplogroups and their sublineages in Amerindian populations (Geppert et al., 2011; Jota et al., 2011; Bisso-Machado et al., 2011).

The most recent mtDNA reviews were published four years ago and involved sequence variability in the hypervariable region 1 (Hunley et al., 2007; Lewis Jr et al., 2007). Schurr and Sherry (2004), on the other hand, associated data from Y-chromosome markers with mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) results, providing a good picture of the information available at the time. No general review considering both data sets has been published since then.

This review provides a detailed, comprehensive survey of Y-chromosome haplogroup frequency variation in 68 populations involving 1,814 individuals. In addition, specific information on Y-STR markers for 29 populations and 590 subjects is given. The haplogroup mtDNA data included 108 populations involving a total of 6,697 persons. Geographic and linguistic factors that may have influenced this variation were carefully considered, leading to a global, overview of the genetic pattern associated with these markers in South Amerindians. Information on mtDNA sequencing studies is also supplied.

Materials and Methods

The data used in this review were obtained from 17 primary surveys of the Y-chromosome and 66 primary surveys of mtDNA. These studies were retrieved through PubMed and by searching the reference lists of the corresponding papers. Haplogroup frequencies were obtained by direct counting. Intra- and inter-populational diversity was calculated with AMOVA (Weir and Cockerham, 1984; Excoffier et al., 1992; Weir, 1996) using Arlequin 3.5.1.2 software (Excoffier and Lischer, 2010). AMOVA was also used to estimate the level of differentiation between and within 17 pre-defined language and 7 geographical categories, respectively. The distribution patterns of the mtDNA haplogroup frequencies were established by generating isoline maps using IDRISI 16.0 software (IDRISI Taiga) (Eastman, 2006). Spearman’s correlation coefficients were calculated with PASW Statistics 18 software. Average heterozygosity (ah) was calculated with Arlequin 3.5.1.2 software.

Results and Discussion

Table 1 gives the distribution of the Q and non-Q-chromosomes (defined by a set of SNPs), as well as linguistic and geographical information for the samples considered. The samples were distributed from latitude 11° North to 45° South and longitude 46° to 76° West, with the individuals involved speaking 23 languages. Sample sizes varied widely from 1 to 151 individuals. Twenty-two of the studies involved less than 10 persons. Unfortunately, there is no standardization on the number of SNPs studied and in most cases only the M242 and M3 markers (which define the Asian/Native American paragroup Q* and its autochthonous Native American sublineage Q1a3a*, respectively; Pena et al., 1995; Bortolini et al., 2003; Seielstad et al., 2003) were investigated. This fact precludes a complete, precise view of the distribution of Q1a3a sublineages and other Q clade chromosomes in South America. For this reason, the information in Table 1 was limited to the frequencies of the Q and non-Q-lineages only. Note that non-Q-chromosomes (which, for the reasons given above, could not be identified in sublineages) were identified in ∼50% of the tribal groups. For some of these populations admixture with non-Indians is known and could be the source of these non-Q chromosomes (for example, Mapuche and Guarani; Marrero et al., 2007; Bailliet et al., 2009; Blanco-Verea et al., 2010). Overall, the numbers presented in Table 1 indicate a higher presence of non-Q lineages in southern populations than in those of the northern/Amazonian region, probably because of greater admixture with non-Indians in the former than in the latter. However, for some isolated groups such as the Yanomámi, it is unlikely that admixture explains the findings. In these cases other causes are more probable, such as the presence of unknown autochthonous lineages and/or known Q lineages whose defining markers were not tested.

Table 1.

The distribution of Q and non-Q lineages and linguistic and geographical information for the samples considered.

| Populations (n)1 | Haplogroup (%)

|

Language2 | Geographical coordinates | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q lineages/Amerindian origin | Non-Q lineages | ||||

| Wayuu (19) | 69 | 31 | Arawakan | 11° N; 73° W | Bortolini et al. (2003) |

| Kogi (17) | 100 | Chibchan | 11° N; 74° W | Rojas et al. (2010) | |

| Barira (12) | 100 | Chibchan | 10° 44′ N; 71° 23′ W | Bortolini et al. (2003) | |

| Arsario (Wiwa) (6) | 100 | Chibchan | 10° 25′ N; 73° 05′ W | Rojas et al. (2010) | |

| Arhuaco (Ijka) (19) | 100 | Chibchan | 9° 04′ N; 73° 59′ W | Rojas et al. (2010) | |

| Warao (12) | 100 | Warao | 9° N; 61° W | Bortolini et al. (2003) | |

| Yukpa (12) | 100 | Carib | 8° 40′ N; 72° 41′ W | Bortolini et al. (2003) | |

| Zenu (52) | 79 | 21 | Spanish3 | 8° 30′ N; 76° W | Bortolini et al. (2003); Rojas et al. (2010) |

| Embera (13) | 92 | 8 | Choco | 7° N; 76° 30′ W | Rojas et al. (2010) |

| Makiritare (25) | 68 | 32 | Carib | 5° 33′ N; 65° 33′ W | Lell et al. (2002) |

| Kali’na (21) | 81 | 19 | Carib | 5° 31′ N; 53° 47′ W | Mazières et al. (2008) |

| Waunana (29) | 100 | Choco | 4° 50′ N; 77° W | Rojas et al. (2010) | |

| Palikur (35) | 94 | 6 | Arawakan | 4° N; 51° 45′ W | Mazières et al. (2008) |

| Macushi (4) | 100 | Carib | 4° N; 60° 50′ W | Lell et al. (2002) | |

| Piaroa (6) | 100 | Salivan | 3° 57′ N; 66° 22′ W | Lell et al. (2002) | |

| Wapishana (2) | 50 | 50 | Arawakan | 3° 07′ N; 60° 03′ W | Lell et al. (2002) |

| Emerillon (9) | 100 | Tupi | 3° N; 53° W | Mazières et al. (2008) | |

| Yanomámi (39) | 38 | 62 | Yanomam | 2° 50′ N; 54° W | Rodriguez-Delfin et al. (1997); Lell et al. (2002) |

| Tiryió (4) | 100 | Carib | 2° N; 56° W | Bortolini et al. (2003) | |

| Apalaí (57) | 98 | 2 | Carib | 1° 20′ N; 54° 40′ W | Rodriguez-Delfin et al. (1997); Bortolini et al. (2003) |

| Wayampi (62) | 100 | Tupi | 1° N; 53° W | Rodriguez-Delfin et al. (1997); Bortolini et al. (2003); Mazières et al. (2008) | |

| Yagua (7) | 100 | Peba-Yaguan | 0° 51′ N; 72° 27′ W | Bortolini et al. (2003) | |

| Ingano (108) | 80 | 20 | Quechuan | 0° 50′ N; 77° W | Bortolini et al. (2003); Rojas et al. (2010) |

| Wai-Wai (9) | 100 | Carib | 0° 40′ S; 58° W | Bisso-Machado et al. (2011) | |

| Urubu-Kaapor (16) | 100 | Tupi | 2°–3° S; 46°–47° W | Bortolini et al. (2003) | |

| Huitoto (4) | 75 | 25 | Witotoan | 2° 14′ S; 72° 19′ W | Bortolini et al. (2003) |

| Arara (15) | 100 | Carib | 3° 30′–4° 20′ S; 53° 0′–54° 10′ W | Rodriguez-Delfin et al. (1997); Bianchi et al. (1998); Bisso-Machado et al. (2011) | |

| Asurini (4) | 100 | Tupi | 3° 35′–4° 12′ S; 49° 40′–52° 26′ W | Bortolini et al. (2003) | |

| Ticuna (59) | 93 | 7 | Ticuna | 4° S; 69° 58′ W; | Bortolini et al. (2003); Rojas et al. (2010) |

| Parakanã (20) | 100 | Tupi | 5° 22′ S; 51° 17′ W | Bortolini et al. (2003) | |

| Xikrin (14) | 100 | Macro-Ge | 5° 55′ S; 51° W | Bortolini et al. (2003); Bisso-Machado et al. (2011) | |

| Suruí (24) | 96 | 4 | Tupi | 5° 58′–10° 50′ S; 48° 39′–61° 10′ W | Underhill et al. (1996); Bisso-Machado et al. (2011) |

| Araweté (4) | 100 | Tupi | 5° 9′ S; 52° 22′ W | Bisso-Machado et al. (2011) | |

| Munduruku (1) | 100 | Tupi | 6° 23′ S; 59° 9′ W | Bisso-Machado et al. (2011) | |

| Jamamadi (3) | 100 | Arauan | 7° 15′ S; 66° 41′ W | Bisso-Machado et al. (2011) | |

| Gorotire (19) | 100 | Macro-Ge | 7° 44′ S; 51° 10′ W | Bortolini et al. (2003); Bisso-Machado et al. (2011) | |

| Krahó (15) | 93 | 7 | Macro-Ge | 8° S; 47° 15′ W | Lell et al. (2002); Bortolini et al. (2003) |

| Kuben-Kran-Kegn (9) | 100 | Macro-Ge | 8° 10′ S; 52° 8′ W | Bisso-Machado et al. (2011) | |

| Tenharim (1) | 100 | Tupi | 8° 20′ S; 62° W | Bisso-Machado et al. (2011) | |

| Mekranoti (9) | 78 | 22 | Macro-Ge | 8° 40′ S; 54° W | Bortolini et al. (2003) |

| Kayapó (10) | 100 | Macro-Ge | 9° S; 53° W | Rodriguez-Delfin et al. (1997) | |

| Karitiana (18) | 100 | Tupi | 9° 30′ S; 64° 15′ W | Underhill et al. (1996); Bisso-Machado et al. (2011) | |

| Cinta-Larga (15) | 100 | Tupi | 9° 50′–12° 30′ S; 59° 10′–60° 50′ W | Bortolini et al. (2003) | |

| Gavião (7) | 100 | Tupi | 10° 10′ S; 61° 8′ W | Bisso-Machado et al. (2011) | |

| Karipuna (1) | 100 | Tupi | 10° 14′ S; 64° 13′ W | Bisso-Machado et al. (2011) | |

| Zoró (6) | 100 | Tupi | 10° 20′ S; 60° 20′ W | Bisso-Machado et al. (2011) | |

| Matsiguenga (28) | 91 | 9 | Arawakan | 10° 47′–12° 51′ S; 73° 17′ -70° 44′ W | Mazières et al. (2008) |

| Pacaás Novos (Wari) (29) | 100 | Chapacura-Wanham | 11° 8′ S; 65° W | Bortolini et al. (2003) | |

| Panoa (5) | 100 | Pano | 12° 55′ S; 65° 12′ W | Lell et al. (2002) | |

| Xavante (15) | 100 | Macro-Ge | 14° S; 52° 30′ W | Bisso-Machado et al. (2011) | |

| Quechua (44) | 73 | 27 | Quechuan | 14° 30′ S; 69° W | Gayà-Vidal et al. (2011) |

| Aymara (59) | 97 | 3 | Aymaran | 17° 68′ S; 69° 16′ W | Gayà-Vidal et al. (2011) |

| Ayoreo (9) | 78 | 22 | Zamucoan | 19° S; 60° 30′ W | Bailliet et al. (2009) |

| Wichí (Mataco) (151) | 48 | 52 | Mataco-Guaicuru | 22° 28′ S; 62° 70′ W | Demarchi and Mitchell (2004); Bailliet et al. (2009) |

| Lengua (36) | 97 | 3 | Mascoian | 22° 45′ S; 58° 5′ W | Bailliet et al. (2009); Bisso-Machado et al. (2011) |

| Chorote (9) | 89 | 21 | Mataco-Guaicuru | 22° 90′ S; 65° 40′ W; | Bailliet et al. (2009) |

| Aché (54) | 98 | 2 | Tupi | 23° 30′–24° 10′ S; 55° 50′–56° 30′ W | Bortolini et al. (2003) |

| Guarani (78) | 77 | 23 | Tupi | 23° 6′ S; 55° 12′ W | Bortolini et al. (2003); Marrero et al.(2007) |

| Pilagá | 47 | 53 | Mataco-Guaicuru | 24° S; 59° W | Demarchi and Mitchell (2004) |

| Colla (63) | 35 | 65 | Quechuan3 | 24° 10′–24° 43′ S; 65° 17′–65° 52′ W | Blanco-Verea et al. (2010); Toscanini et al. (2011) |

| Toba (89) | 88 | 12 | Mataco-Guaicuru | 26° S; 58° W | Demarchi and Mitchell (2004); Bailliet et al. (2009); Toscanini et al. (2011) |

| Kaingang (59) | 69 | 31 | Macro-Ge | 28° S; 51° 20′ W | Bortolini et al. (2003); Marrero et al. (2007); Bisso-Machado et al. (2011) |

| Diaguita (24) | 37 | 63 | Quechuan4 | 28° 20′ S; 67° 43′ W | Blanco-Verea et al. (2010) |

| Mocoví (40) | 60 | 40 | Mataco-Guaicuru | 29° 51′ S; 59° 56′ W | Bailliet et al. (2009) |

| Pehuenche (18) | 83 | 17 | Araucanian | 37° 43′ S; 71° 16′ W | Bailliet et al. (2009) |

| Mapuche (105) | 36 | 64 | Araucanian | 39° 10′–41° 20′ S; 68° 37′–70° 22′ W | Bailliet et al. (2009); Blanco-Verea et al. (2010) |

| Huilliche (26) | 50 | 50 | Araucanian | 41° 16′ S; 73° W | Bailliet et al. (2009) |

| Tehuelche (20) | 65 | 35 | Chon | 45° S; 71° W | Bailliet et al. (2009) |

Arranged according to latitude.

Classification according to Lewis (2009).

Original language is extinct.

The Diaguita spoke originally Kakán, but this language became extinct and was substituted by Quechua.

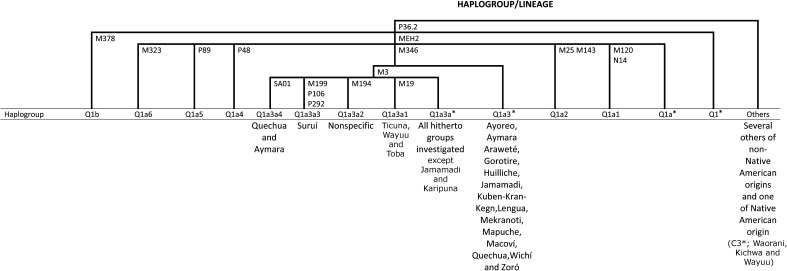

Despite the great variation in the number of Y-SNPs used in these studies, Figure 1 illustrates some of the trends that were observed: The autochthonous Native American Q1a3a* is almost always the most prevalent, whereas its sublineages (Q1a3a1, Q1a3a2, Q1a3a3 and Q1a3a4) seem to have more restricted geographical distributions. The second most prevalent, Q1a3*, appears to occur equally in all regions, suggesting its presence among the first settlers of South America. The other known Q clade chromosomes (Q1*, Q1a*, Q1a1, Q1a2, Q1a4, Q1a5, Q1a6 and Q1b) have not yet been identified in South America. Only one non-Q-chromosome (C3*) of probable native origin has been described in northwest South Amerindian populations (Figure 1; Geppert et al., 2011).

Figure 1.

Y-chromosome phylogenetic tree considering only the Q derived lineages. Note: The letters and numbers in the branches indicate the name of the loci where the mutations occurred, leading to the haplogroup classification. The data for this tree were compiled from the references in Table 1, plus Santos et al. (1995), Underhill et al. (1997, 2001), Karafet et al. (1997, 1999, 2008), Carvalho-Silva et al. (1999), Vallinoto et al. (1999), Bortolini et al. (2002), The Y-Chromosome Consortium (2002) and Geppert et al. (2011).

The nature of some evolutionary and demographic scenarios, mediated by men, in native American populations has also been evaluated by using Y microsatellite markers (Y-STRs), which have a much faster evolutionary rate than SNPs. Y-STRs allow the retrieval of population and chromosome evolutionary histories. For example, STR data have been used to estimate that the mutations that gave rise to the Q1a3a1 and Q1a3a4 sublineages occurred 7,972 ± 2,916 and 5,280 ± 1,330 years ago, probably in northwest South America and the Andean region, respectively (Bortolini et al., 2003; Jota et al., 2011).

Table 2 shows the STR allele frequencies observed in 29 South Amerindian populations, based only on Q clade chromosomes. In this compilation, we considered only studies containing information on the allele frequencies for each population individually. There was considerable variation in the number of samples tested in each study, the number of tribes, and the number of individuals per tribe. Depending on the locus considered, the number of alleles observed ranged from one to eight, with some of them appearing in only one study while others were present in almost all populations. Based on the most prevalent alleles per locus we reconstructed a probable haplotype of the ancient Native American Q-clade chromosome (ANAQC) as: 13(DYS19)-12(DYS388)-14(DYS389I)-31(DYS389II)-2 4(DYS390)-10(DYS391)-14(DYS392)-13(DYS393)-14(DYS437)-11(DYS438)-12(DYS439)-20(DYS448)-15(D YS456)-16(DYS458)-22(DYS635). Using this information and additional data for these loci (except DYS388) reported in the Y Chromosome Haplotype Reference Database we found no matches in 36,448 haplotypes (245 populations). Although we found no complete identity with our estimated ANAQC, three one-step neighbor haplotypes were encountered, two in individuals with an admixed ancestry living in Latin American countries and one in a Native American individual (Kaqchiquel).

Table 2(a).

Y-Q-chromosome STR studies in distinct South Amerindian samples in which allele frequencies can be assessed (Part A).

| Ref. (n)

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STR (allele) | Aché (48)2 | Apalaí (9)1 | Arara (8)1 | Aymara (57)9 | Ayoreo (2)7 | Barira (12)2 | Diaguita (9)8 | Guarani (47)4, 5 | Ingano (8)2 | Kaingang (17)5 | Kayapó (10)1 | Colla (22)6, 8 | Lengua (6)7 | Mapuche (24)6, 8 | Mekranoti (5)2 |

| DYS19 (12) | 0.020 | 0.250 | |||||||||||||

| DYS19 (13) | 1.000 | 0.820 | 0.920 | 1.000 | 0.790 | 0.620 | 0.300 | 0.910 | 0.500 | 0.830 | 0.600 | ||||

| DYS19 (14) | 0.160 | 1.000 | 0.080 | 0.190 | 0.130 | 0.300 | 0.090 | 0.330 | 0.040 | 0.400 | |||||

| DYS19 (15) | 0.020 | 0.350 | 0.170 | 0.130 | |||||||||||

| DYS19 (16) | 0.050 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS19 total | |||||||||||||||

| DYS388 (12) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.750 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| DYS388 (13) | 0.120 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS388 (14) | 0.130 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS388 (17) | |||||||||||||||

| DYS388 total | |||||||||||||||

| DYS389I (12) | 0.020 | 0.280 | 0.180 | 0.040 | 0.160 | 0.040 | |||||||||

| DYS389I (13) | 0.470 | 0.500 | 0.220 | 0.020 | 0.820 | 0.410 | 0.500 | 0.750 | |||||||

| DYS389I (14) | 0.510 | 0.500 | 0.780 | 0.550 | 0.550 | 0.170 | 0.210 | ||||||||

| DYS389I (15) | 0.150 | 0.170 | |||||||||||||

| DYS389I total | |||||||||||||||

| DYS389II (17) | |||||||||||||||

| DYS389II (18) | |||||||||||||||

| DYS389II (19) | |||||||||||||||

| DYS389II (26) | 0.060 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS389II (27) | 0.160 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS389II (28) | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.120 | ||||||||||||

| DYS389II (29) | 0.090 | 0.500 | 0.150 | 0.290 | 0.090 | 0.500 | 0.290 | ||||||||

| DYS389II (30) | 0.370 | 0.500 | 0.440 | 0.130 | 0.470 | 0.180 | 0.170 | 0.420 | |||||||

| DYS389II (31) | 0.450 | 0.560 | 0.620 | 0.060 | 0.500 | 0.250 | |||||||||

| DYS389II (32) | 0.070 | 0.080 | 0.090 | 0.170 | 0.040 | ||||||||||

| DYS389II (33) | 0.140 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS389II (34) | |||||||||||||||

| DYS389II total | |||||||||||||||

| DYS390 (20) | |||||||||||||||

| DYS390 (21) | 0.230 | 0.120 | 0.070 | 0.060 | 0.100 | 0.040 | |||||||||

| DYS390 (22) | 0.110 | 0.130 | 0.040 | ||||||||||||

| DYS390 (23) | 1.000 | 0.330 | 0.880 | 0.560 | 0.080 | 0.330 | 0.080 | 0.250 | 0.100 | 0.640 | 0.330 | 0.420 | 0.400 | ||

| DYS390 (24) | 0.330 | 0.250 | 1.000 | 0.920 | 0.450 | 0.680 | 0.370 | 0.940 | 0.700 | 0.180 | 0.670 | 0.330 | 0.600 | ||

| DYS390 (25) | 0.120 | 0.220 | 0.090 | 0.250 | 0.100 | 0.210 | |||||||||

| DYS390 (26) | 0.020 | 0.130 | 0.140 | ||||||||||||

| DYS390 (27) | |||||||||||||||

| DYS390 total | |||||||||||||||

| DYS391 (9) | 0.020 | 0.210 | |||||||||||||

| DYS391 (10) | 1.000 | 0.820 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.890 | 0.210 | 0.860 | 0.820 | 1.000 | 0.750 | 1.000 | ||||

| DYS391 (11) | 0.140 | 0.110 | 0.790 | 0.140 | 0.180 | 0.040 | |||||||||

| DYS391 (12) | 0.020 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS391 total | |||||||||||||||

| DYS392 (11) | 0.060 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS392 (12) | 0.140 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS392 (13) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.920 | 0.070 | 0.120 | 0.350 | 0.700 | 0.050 | 0.170 | 1.000 | |||||

| DYS392 (14) | 1.000 | 0.470 | 0.500 | 0.080 | 0.450 | 0.720 | 0.880 | 0.530 | 0.300 | 0.360 | 0.830 | 0.710 | |||

| DYS392 (15) | 0.040 | 0.500 | 0.330 | 0.210 | 0.060 | 0.090 | 0.170 | 0.120 | |||||||

| DYS392 (16) | 0.470 | 0.220 | 0.360 | ||||||||||||

| DYS392 (17) | 0.020 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS392 (18) | |||||||||||||||

| DYS392 total | |||||||||||||||

| DYS393 (11) | 0.480 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS393 (12) | 0.220 | 0.120 | 0.080 | 0.090 | 0.120 | 0.060 | 0.400 | 0.090 | 0.400 | ||||||

| DYS393 (13) | 1.000 | 0.780 | 0.880 | 0.440 | 1.000 | 0.670 | 0.340 | 0.760 | 0.590 | 0.600 | 0.550 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.600 | |

| DYS393 (14) | 0.560 | 0.920 | 0.330 | 0.090 | 0.120 | 0.350 | 0.360 | ||||||||

| DYS393 (15) | |||||||||||||||

| DYS393 (16) | |||||||||||||||

| DYS393 total | |||||||||||||||

| DYS437 (8) | |||||||||||||||

| DYS437 (9) | |||||||||||||||

| DYS437 (11) | 0.040 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS437 (14) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.930 | 0.590 | 1.000 | 0.920 | |||||||||

| DYS437 (15) | 0.070 | 0.410 | 0.040 | ||||||||||||

| DYS437 total | |||||||||||||||

| DYS438 (9) | |||||||||||||||

| DYS438 (10) | 0.050 | 0.220 | 0.040 | ||||||||||||

| DYS438 (11) | 0.930 | 0.670 | 0.860 | 0.590 | 1.000 | 0.920 | |||||||||

| DYS438 (12) | 0.020 | 0.110 | 0.140 | 0.410 | |||||||||||

| DYS438 (16) | 0.040 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS438 total | |||||||||||||||

| DYS439 (9) | 0.050 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS439 (10) | 0.060 | 0.130 | |||||||||||||

| DYS439 (11) | 0.160 | 0.220 | 0.070 | 0.230 | 0.050 | 0.220 | |||||||||

| DYS439 (12) | 0.240 | 0.450 | 0.640 | 0.590 | 0.360 | 0.390 | |||||||||

| DYS439 (13) | 0.370 | 0.330 | 0.290 | 0.060 | 0.270 | 0.260 | |||||||||

| DYS439 (14) | 0.230 | 0.060 | 0.270 | ||||||||||||

| DYS439 total | 0.200 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS448 (18) | |||||||||||||||

| DYS448 (19) | 0.110 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS448 (20) | 0.770 | 0.800 | |||||||||||||

| DYS448 (21) | 0.120 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS448 (22) | |||||||||||||||

| DYS448 total | |||||||||||||||

| DYS456 (11) | 0.020 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS456 (13) | 0.050 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS456 (14) | 0.020 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS456 (15) | 0.800 | 0.900 | |||||||||||||

| DYS456 (16) | 0.090 | 0.100 | |||||||||||||

| DYS456 (17) | 0.020 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS456 total | |||||||||||||||

| DYS458 (13) | 0.050 | 0.100 | |||||||||||||

| DYS458 (15) | 0.030 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS458 (16) | 0.490 | 0.700 | |||||||||||||

| DYS458 (17) | 0.250 | 0.200 | |||||||||||||

| DYS458 (18) | 0.140 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS458 (19) | 0.040 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS458 total | |||||||||||||||

| DYS635 (22) | 0.820 | 0.700 | |||||||||||||

| DYS635 (23) | 0.160 | 0.300 | |||||||||||||

| DYS635 (24) | |||||||||||||||

| DYS635 (26) | 0.020 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS635 total | |||||||||||||||

Table 3 shows the results of the molecular analysis of variance for populations structured by language or geography based on the data in Table 2. The estimates were calculated for each STR locus because testing heterogeneity prevented haplotype identification. As expected, most of the diversity was attributable to intrapopulation variation, with one exception (DYS437) that was explained by the fixation of allele 14 in 40% of the populations, whereas only allele 8 was found in the Wichí. In contrast, significant variation among subdivisions was detected for only six loci (DYS398I, DYS391, DYS392, DYS393, DYS437 and DYS456) and in five out of these six it was attributable to geography. There was also considerable inter-population/within subdivision variability (significant in 28 of 30 evaluations), with the average percentage being 16% for geography and 21% for language.

Table 3.

Analysis of molecular variance of the distinct alleles of the Y-Q STRs in relation to the language and geography of the populations tested.

| STR loci (structured by) | Among subdivisions | Among populations within subdivisions | Within populations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DYS19 (Language)1 | 0 | 0.311* | 0.689* |

| DYS19 (Geography)2 | 0 | 0.332* | 0.668* |

| DYS388 (Language)1 | 0.045 | 0.317* | 0.638* |

| DYS388 (Geography)2 | 0.091 | 0.240* | 0.669* |

| DYS389I (Language)1 | 0.227* | 0.030 | 0.743* |

| DYS389I (Geography)2 | 0.116 | 0.148* | 0.736* |

| DYS389II (Language)1 | 0.036 | 0.077* | 0.887* |

| DYS389II (Geography)2 | 0 | 0.125* | 0.875* |

| DYS390 (Language)1 | 0.008 | 0.326* | 0.666* |

| DYS390 (Geography)2 | 0 | 0.359* | 0.642* |

| DYS391 (Language)1 | 0 | 0.385* | 0.615* |

| DYS391 (Geography)2 | 0.253* | 0.131* | 0.616* |

| DYS392 (Language)1 | 0.005 | 0.319* | 0.676* |

| DYS392 (Geography)2 | 0.007* | 0.262* | 0.661* |

| DYS393 (Language)1 | 0 | 0.331* | 0.669* |

| DYS393 (Geography)2 | 0.177* | 0.167* | 0.656* |

| DYS437 (Language)1 | 0.289 | 0.273* | 0.438* |

| DYS437 (Geography)2 | 0.390* | 0.213* | 0.397* |

| DYS438 (Language)1 | 0.048 | 0.025 | 0.927* |

| DYS438 (Geography)2 | 0.023 | 0.054* | 0.923* |

| DYS439 (Language)1 | 0.019 | 0.054* | 0.929* |

| DYS439 (Geography)2 | 0.055 | 0.034* | 0.911* |

| DYS448 (Language)1 | 0 | 0.148* | 0.852* |

| DYS448 (Geography)2 | 0 | 0.073* | 0.927* |

| DYS456 (Language)1 | 0 | 0.078* | 0.922* |

| DYS456 (Geography)2 | 0.017* | 0.044* | 0.939* |

| DYS458 (Language)1 | 0 | 0.144* | 0.856* |

| DYS458 (Geography)2 | 0.043 | 0.069* | 0.888* |

| DYS635 (Language)1 | 0 | 0.278* | 0.722* |

| DYS635 (Geography)2 | 0 | 0.128* | 0.872* |

Language: Tupi: Aché, Guarani, Parakanã, Wayampi; Carib: Apalaí, Arara, Yukpa; Macro-Ge: Kaingang, Kayapó, Mekranoti; Quechua: Diaguita, Quechua, Ingano; Mataco-Guaicuru: Mocoví, Toba, Wichí, Pilagá; Isolated languages and others with only one population were included as a sixth group.

Geography: Amazonia/Central Brazilian Plateau: Apalaí, Arara, Kayapó, Mekranoti, Pacaás Novos, Parakanã, Ticuna, Warao, Wayampi, Yanomámi; Southern Brazil: Guarani and Kaingang; Chaco: Ache, Ayoreo, Lengua, Mocoví, Pilagá, Toba, Wichí; Andes: Aymara, Barira, Diaguita, Kolla, Quechua, Wayuu, Yukpa, Zenu.

Significant values (p = 0.05). Negative values were adjusted to zero.

Table 4 summarizes the information on sequencing studies of mitochondrial DNA. The mtDNA genome of representative individuals from 35 populations has been entirely sequenced, as reported in six publications (Ingman et al., 2000; Kivisild et al., 2006; Tamm et al., 2007; Fagundes et al., 2008; Perego et al., 2009, 2010). However, the analyses performed did not consider the within South Amerindian relationships and were mostly concerned with interethnic or interhaplogroup comparisons. Based on 86 complete Amerindian genomes, Fagundes et al. (2008) concluded that the prehistoric colonization of the Americas involved a single founding population, with an initial differentiation from Asia occurring in Beringia that ended around 19,000–23,000 years ago, with a moderate bottleneck. Expansion into the New World would have occurred about 18,000 years ago. An extensive 5.76 kb analysis by Dornelles et al. (2005) established that haplogroup X is not present in extant South American Indians.

Table 4.

Mitochondrial DNA sequencing studies in South Amerindian populations.

Ancient DNA.

Sequencing included almost half of the genome (sites 7,148–15,976).

The most extensive set of data involves the highly variable segment 1 (HVS-I) that has been studied in 92 populations and reported in 30 papers; surveys that have included the HVS-II region are much less common (10 articles) (Table 4). For HVS-I, Merriwether et al. (2000) provided an excellent example of how intrapopulation variability in the Yanomámi could be interpreted in a historical and demographical context and relating it to other Amerindian and Asian data. They studied 129 Yanomámi sequences from individuals in eight villages and compared their haplotypes with those of other Asian and New World populations, in a total of 482 unique haplotypes. Interestingly, the pairwise inter-population gene flow estimates were lower between some pairs of Yanomámi villages than between them and four other South Amerindian groups.

With regard to intrapopulation variability, as measured by Θk, Fuselli et al. (2003) and Corella et al. (2007) reported extensive variation for 14 and 27 Central and Southern Amerindian populations, respectively (e.g., from 0.659 for the Quechua of Peru to 0.011 for the Xavante of the Brazilian Mato Grosso). Intra- and intergroup nucleotide diversity was calculated by Melton et al. (2007) for 20 of these Amerindian groups, whereas Barbieri et al. (2011) compared the sources of variation among North, Central and South Amerindians in 51 populations; the latter authors observed 3% variation among the three sets, 21% variation among populations within the subcontinent and 76% variation within populations.

To explore the mtDNA data further we compiled the prevalences of haplogroups A–D for 109 populations, in a total of 6,697 individuals distributed between latitude 11° North and 54° South, and longitude 46° to 78° West (Table 5). Sample sizes varied widely, from only one subject tested (Jebero) up to 491 (Yanomámi). The haplogroup frequencies reported in 52 articles also varied widely. The presence of mtDNA genomes of probable non-Amerindian origin was rare in all regions and populations, in contrast to the Y-SNP data (Table 1). Asymmetrical sex-mediated admixture was common during the first centuries of South American colonization, and involved mostly European men and Amerindian/African women. The main consequences of this historical contact was the formation of mestizos and the present-day national societies; the former are characterized by a composite genome, with the majority of Y-chromosomes being of European origin, while their mtDNA derives from Amerindian or African sources (Bortolini et al., 1999; Alves-Silva et al., 2000; Carvalho-Silva et al., 2001; Salzano and Bortolini, 2002). Asymmetrical mating could also explain the introduction of non-Amerindian Y-chromosomes into the tribes, while the autochthonous mtDNA genomes were preserved. However, the admixture dynamics are probably different from those observed in urban groups since they normally involve Amerindian women who live on reservations and men who live near the border of the reservations. In this situation, the children normally remain with their mothers. This phenomenon has been described for Guarani Indians (Marrero et al., 2007), but the data presented here indicate that it could be much more common than previously thought.

Table 5.

Mitochondrial DNA haplogroup and linguistic and geographical information for the samples considered.

| Population (n)1 | Haplogroups (%)

|

Language | Geographical coordinates | References | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | Others2 | |||||

| Wayuu (89) | 26 | 28 | 45 | 0 | 1 | Arawakan | 11° N; 73° W | Mesa et al. (2000); Keyeux et al. (2002); Melton et al. (2007) | |

| Kogi (153) | 67 | 0 | 33 | 0 | 0 | Chibchan | 11° N; 74° W | Keyeux et al. (2002); Melton et al. (2007); Rojas et al. (2010) | |

| Arsario (Wiwa) (76) | 63 | 0 | 37 | 0 | 0 | Chibchan | 10° 25′ N; 73° 05′ W | Keyeux et al. (2002); Melton et al. (2007); Rojas et al. (2010) | |

| Chimila (35) | 88 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 3 | Chibchan | 10° 16′ N; 74° 4′ W | Keyeux et al. (2002) | |

| Arhuaco (Ijka) (134) | 87 | 1 | 12 | 0 | 0 | Chibchan | 9° 04′ N; 73° 59′ W | Keyeux et al. (2002); Melton et al. (2007); Rojas et al. (2010) | |

| Yukpa (88) | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Carib | 8° 40′ N; 72° 41′ W | Keyeux et al. (2002) | |

| Zenu (107) | 19 | 38 | 36 | 5 | 2 | Spanish | 8° 30′ N; 76° W | Mesa et al. (2000); Keyeux et al. (2002); Torres et al. (2006) | |

| Embera (43) | 53 | 35 | 2 | 5 | 5 | Choco | 7° N; 76° 30′ W | Mesa et al. (2000); Keyeux et al. (2002) | |

| Tule-Cuna (30) | 50 | 27 | 20 | 0 | 3 | Chibchan | 6° 56′ N; 76° 45′ W | Keyeux et al. (2002) | |

| Guane-Butaregua (33) | 12 | 64 | 0 | 24 | 0 | Chibchan | 6° 15′ N; 73° 15′ W | Keyeux et al. (2002) | |

| Cubeo (22) | 27 | 18 | 50 | 5 | 0 | Tucanoan | 5° 9′ N; 70° 18W | Torres et al. (2006) | |

| Makiritare (10) | 20 | 0 | 70 | 10 | 0 | Carib | 5° 33′ N; 65° 33′ W | Torroni et al. (1993) | |

| Kali’ na (Galibi) (29) | 7 | 41 | 38 | 7 | 7 | Carib | 5° 31′ N; 53° 47′ W | Mazières et al. (2008) | |

| Guahibo (99) | 52 | 3 | 33 | 0 | 12 | Guahiban | 5° N; 69° W | Keyeux et al. (2002); Vona et al. (2005); Torres et al. (2006) | |

| Waunana (161) | 21 | 49 | 16 | 14 | 0 | Choco | 4° 50′ N; 77° W | Keyeux et al. (2002); Tamm et al. (2007); Rojas et al. (2010) | |

| Palikúr (64) | 1 | 47 | 4 | 47 | 1 | Arawakan | 4° N; 51° 45′ W | Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001); Mazières et al. (2008) | |

| Macushi (10) | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 0 | Carib | 4° N; 60° 50′ W | Torroni et al. (1993) | |

| Páez (51) | 59 | 12 | 27 | 2 | 0 | Páez | 3° 9′ N; 75° 28′ W | Keyeux et al. (2002); Torres et al. (2006) | |

| Ocaina (2) | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | Witotoan | 3° 58′ N; 68° 2′ W | Torres et al. (2006) | |

| Jebero (1) | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | Cahuapanan | 3° 58′ N; 68° 2′ W | Torres et al. (2006) | |

| Piaroa (28) | 36 | 11 | 21 | 32 | 0 | Salivan | 3° 57′ N; 66° 22′ W | Torroni et al. (1993); Keyeux et al. (2002) | |

| Desano (2) | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 | Tucanoan | 3° 24′ N; 69° 40′ W | Torres et al. (2006) | |

| Wapishana (12) | 0 | 25 | 8 | 67 | 0 | Arawakan | 3° 07′ N; 60° 03′ W | Torroni et al. (1993) | |

| Emerillon (30) | 30 | 70 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Tupi | 3° N; 53° W | Mazières et al. (2008) | |

| Guambiano (23) | 4 | 4 | 79 | 13 | 0 | Barbacoan | 2° 6′ N; 76° 23′ W | Keyeux et al. (2002) | |

| Yanomámi (491) | 2 | 25 | 50 | 19 | 4 | Yanomam | 2° 50′ N; 54° W | Torroni et al. (1992, 1993); Easton et al. (1996); Merriwether et al. (2000); Williams et al. (2002); Silva Jr et al. (2003) | |

| Guayabero (30) | 50 | 17 | 13 | 0 | 20 | Guahiban | 2° 25′ N; 71° 4′ W | Keyeux et al. (2002) | |

| Curripaco (22) | 41 | 36 | 23 | 0 | 0 | Arawakan | 2° 10′ N; 68° 54′ W | Keyeux et al. (2002); Torres et al. (2006) | |

| Tiriyó (32) | 9 | 19 | 22 | 47 | 3 | Carib | 2° N; 56° W | Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001); Silva Jr et al. (2003) | |

| Nukak (20) | 0 | 20 | 80 | 0 | 0 | Maku | 1° 44′ N; 70° 44′ W | Keyeux et al. (2002) | |

| Apalaí (120) | 37 | 1 | 30 | 32 | 0 | Carib | 1° 20′ N; 54° 40′ W | Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001); Mazières et al. (2008) | |

| Cayapa (120) | 29 | 40 | 9 | 22 | 0 | Barbacoan | 1° 17′ N; 78° 50′ W | Rickards et al. (1999) | |

| Wayampi (99) | 62 | 11 | 8 | 19 | 0 | Tupi | 1° N; 53° W | Santos et al. (1996); Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001); Silva Jr et al. (2003); Mazières et al. (2008) | |

| Siona (12) | 75 | 17 | 8 | 0 | 0 | Tucanoan | 0° 6′ N; 75° 36′ W | Keyeux et al. (2002) | |

| Pasto (9) | 67 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Barbacoan | 0° 58′ N; 77° 44′ W | Keyeux et al. (2002) | |

| Yagua (12) | 25 | 0 | 67 | 8 | 0 | Peba-Yaguan | 0° 51′ N; 72° 27′ W | Torres et al. (2006) | |

| Ingano (111) | 18 | 38 | 42 | 0 | 2 | Quechuan | 0° 50′ N; 77° W | Mesa et al. (2000); Keyeux et al. (2002); Torres et al. (2006); Rojas et al. (2010) | |

| Tucano (17) | 0 | 18 | 47 | 35 | 0 | Tucanoan | 0° 42′ N; 69° 53′ W | Keyeux et al. (2002) | |

| Coreguaje (69) | 4 | 20 | 66 | 6 | 4 | Tucanoan | 0° 38′ N; 76° 8′ W | Keyeux et al. (2002); Tamm et al. (2007) | |

| Awa-Juriti (18) | 0 | 72 | 11 | 0 | 17 | Tucanoan | 0° 16′ N; 70° 45′ W | Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001) | |

| Muinane (19) | 11 | 21 | 37 | 26 | 5 | Witotoan | 0° 11′ N; 73° 25′ W | Keyeux et al. (2002) | |

| Poturujara (23) | 44 | 0 | 26 | 30 | 0 | Tupi | 0° 18′ S; 55° 18′ W | Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001); Silva Jr et al. (2003) | |

| Katuena (23) | 26 | 9 | 35 | 30 | 0 | Carib | 0° 40′ S; 57° 30′ W | Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001); Silva Jr et al. (2003) | |

| Wai-wai (26) | 15 | 15 | 43 | 27 | 0 | Carib | 0° 40′ S; 58° W | Bonatto and Salzano (1997) | |

| Urubu Kaapor (42) | 21 | 31 | 14 | 29 | 5 | Tupi | 2°–3° S; 46°–47° W | Torroni et al. (1992, 1993); Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001); Dornelles et al. (2005) | |

| Huitoto (35) | 23 | 3 | 25 | 46 | 3 | Witotoan | 2° 14′ S; 72° 19′ W | Keyeux et al. (2002); Torres et al. (2006) | |

| Arara (70) | 54 | 20 | 26 | 0 | 0 | Carib | 3° 30′–4° 20′ S; 53° 0′–54° 10′ W | Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001); Ribeiro-dos-Santos et al. (2001); Silva Jr et al. (2003); Bisso-Machado (2010, MSc Dissertation, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.) | |

| Awa-Guajá (53) | 13 | 87 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Tupi | 3° 30′ S; 46° 40′ W | Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001) | |

| Asurini (24) | 4 | 54 | 17 | 21 | 4 | Tupi | 3° 35′–4° 12′ S; 49° 40′–52° 26′ W | Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001) | |

| Piapoco (39) | 18 | 3 | 15 | 5 | 59 | Arawakan | 3° 36′ S; 70° 23′ W | Torres et al. (2006) | |

| Puinave (19) | 5 | 16 | 58 | 16 | 5 | Puinave | 3° 36′ S; 70° 23′ W | Torres et al. (2006) | |

| Sáliba (13) | 15 | 0 | 55 | 15 | 15 | Salivan | 3° 49′ S; 70° 9′ W | Torres et al. (2006) | |

| Ticuna (371) | 20 | 11 | 35 | 33 | 1 | Ticuna | 4° S; 69° 58′ W | Schurr et al. (1990); Mesa et al. (2000); Torres et al. (2006); Mendes-Junior and Simões (2009); Rojas et al. (2010) | |

| Parakanã (31) | 6 | 39 | 32 | 23 | 0 | Tupi | 5° 22′ S; 51° 17′ W | Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001); Bisso-Machado (2010, MSc Dissertation) | |

| Xikrin (33) | 30 | 64 | 3 | 3 | 0 | Macro-Ge | 5° 55′ S; 51° W | Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001); Dornelles et al. (2005); Bisso-Machado (2010, MSc Dissertation) | |

| Suruí (44) | 7 | 4 | 0 | 89 | 0 | Tupi | 5° 58′ -10° 50′ S; 48° 39′ -61° 10′ W | Bonatto and Salzano (1997); Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001) | |

| Araweté (18) | 39 | 0 | 50 | 11 | 0 | Tupi | 5° 9′ S; 52° 22′ W | Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001) | |

| Munduruku (92) | 12 | 17 | 9 | 58 | 4 | Tupi | 6° 23′ S; 59° 9′ W | Torroni et al. (1992, 1993); Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001); Marrero et al. (2007); Bisso-Machado (2010, MSc Dissertation) | |

| Marubo (10) | 10 | 0 | 60 | 30 | 0 | Panoan | 6° 47′ S; 72° 80′ W | Torroni et al. (1993) | |

| Jamamadi (23) | 0 | 0 | 96 | 4 | 0 | Arauan | 7° 15′ S; 66° 41′ W | Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001); Bisso-Machado (2010, MSc Dissertation) | |

| Yungay (38) | 5 | 45 | 34 | 16 | 0 | Quechuan | 7° 26′ S; 77° 4′ W | Lewis Jr et al. (2007) | |

| Ancash (33) | 9 | 52 | 18 | 21 | 0 | Quechua | 7° 41′ S; 77° 6′ W | Lewis Jr et al. (2005) | |

| Gorotire (11) | 28 | 18 | 18 | 36 | 0 | Macro-Ge | 7° 44′ S; 51° 10′ W | Bisso-Machado (2010, MSc Dissertation) | |

| Krahó (14) | 29 | 57 | 14 | 0 | 0 | Macro-Ge | 8° S; 47° 15′ W | Torroni et al. (1993) | |

| Kuben-Kran-Kegn (19) | 58 | 26 | 6 | 10 | 0 | Macro-Ge | 8° 10′ S; 52° 8′ W | Bisso-Machado (2010, MSc Dissertation) | |

| Mekranoti (19) | 26 | 63 | 11 | 0 | 0 | Macro-Ge | 8° 40′ S; 54° W | Dornelles et al. (2005); Bisso-Machado (2010, MSc Dissertation) | |

| Kubenkokre (4) | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Macro-Ge | 8° 43′ S; 53° 23′ W | Marrero et al. (2007) | |

| Kayapó (13) | 46 | 54 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Macro-Ge | 9° S; 53° W | Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001) | |

| Karitiana (19) | 0 | 11 | 0 | 89 | 0 | Tupi | 9° 30′ S; 64° 15′ W | Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001) | |

| Cinta-Larga (45) | 25 | 0 | 20 | 53 | 2 | Tupi | 9° 50′–12° 30′ S; 59° 10′–60° 50′ W | Lobato-da-Silva et al. (2001); Dornelles et al. (2005); Bisso-Machado (2010, MSc Dissertation) | |

| Gavião (27) | 15 | 15 | 0 | 70 | 0 | Tupi | 10° 10′ S; 61° 8′ W | Ward et al. (1996) | |

| Tupe (16) | 0 | 69 | 31 | 0 | 0 | Aymaran | 10° 16′ S; 75° 47′ W | Lewis Jr et al. (2007) | |

| Txukahamãe (2) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Macro-Ge | 10° 20′ S; 53° 5′ W | Dornelles et al. (2005) | |

| Zoró (30) | 20 | 7 | 13 | 60 | 0 | Tupi | 10° 20′ S; 60° 20′ W | Ward et al. (1996) | |

| Matsiguenga (38) | 5 | 92 | 0 | 3 | 0 | Arawakan | 10° 47′–12° 51′ S; 73° 17′ -70° 44′ W | Mazières et al. (2008) | |

| Kokraimoro (2) | 50 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Macro-Ge | 10° 49′ S; 55° 27′ W | Marrero et al. (2007) | |

| Pacaás Novos (Wari) (30) | 40 | 30 | 27 | 3 | 0 | Chapacura-Wanh am | 11° 8′ S; 65° W | Bisso-Machado (2010, MSc Dissertation) | |

| Tayacaja (61) | 21 | 33 | 13 | 30 | 3 | Quechuan | 12° 24′ S; 74° 34′ W | Fuselli et al. (2003) | |

| Arequipa (22) | 9 | 68 | 14 | 9 | 0 | Quechua | 13° 13′ S; 72° 11′ W | Fuselli et al. (2003) | |

| Trinitario (35) | 14 | 40 | 37 | 3 | 6 | Arawakan | 14° S; 65° W | Bert et al. (2001) | |

| Xavánte (25) | 16 | 84 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Macro-Ge | 14° S; 52° 30′ W | Ward et al. (1996) | |

| Movima (22) | 9 | 9 | 64 | 18 | 0 | Movima | 14° 26′ S; 65° 53′ W | Bert et al. (2001) | |

| Quechua (232) | 14 | 62 | 15 | 9 | 0 | Quechuan | 14° 30′ S; 69° W | Merriwether et al. (1995); Bert et al. (2001); Silva Jr et al. (2003); Lewis Jr et al. (2007); Corella et al. (2007); Barbieri et al. (2011); Gayà-Vidal et al. (2011) | |

| Chimane (Moseten) (71) | 39 | 54 | 3 | 0 | 4 | Chimane | 14° 41′ S; 66° 50′ W | Bert et al. (2001); Corella et al. (2007); | |

| Ignaciano (22) | 18 | 36 | 41 | 0 | 5 | Arawakan | 15° 1′ S; 66° 4′ W | Bert et al. (2001) | |

| Uro (64) | 11 | 69 | 9 | 11 | 0 | Uru-Chipaya | 15° 45′ S; 69° 53′ W | Barbieri et al. (2011) | |

| Yuracare (28) | 39 | 32 | 21 | 4 | 4 | Yuracare | 17° S; 65° W | Bert et al. (2001) | |

| Aymara (411) | 4 | 76 | 8 | 11 | 1 | Aymaran | 17° 68′ S; 69° 16′ W | Merriwether et al. (1995); Easton et al. (1996); Bert et al. (2001); Lewis Jr et al. (2007); Corella et al. (2007); Barbieri et al. (2011); Gayà-Vidal et al. (2011) | |

| Ayoreo (91) | 0 | 0 | 83 | 17 | 0 | Zamucoan | 19° S; 60° 30′ W | Dornelles et al. (2004) | |

| Wichí (199) | 12 | 51 | 7 | 29 | 1 | Mataco-Guaicuru | 22° 28′ S; 62° 70′ W | Torroni et al. (1993); Bianchi et al. (1995); Bravi et al. (1995); Demarchi et al. (2001); Cabana et al. (2006) | |

| Chorote (34) | 15 | 44 | 23 | 18 | 0 | Mataco-Guaicuru | 22° 90′ S; 65° 40′ W | Bianchi et al. (1995); Bravi et al. (1995) | |

| Humahuaca (46) | 11 | 68 | 17 | 4 | 0 | Spanish | 23° 11′ S; 65° 20′ W | Dipierri et al. (1998) | |

| Aché (63) | 10 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Tupi | 23° 30′–24° 10′ S; 55° 50′–56° 30′ W | Schmitt et al. (2004) | |

| Atacameño (79) | 13 | 73 | 10 | 4 | 0 | Atacama | 23° 50′ S; 68° W | Baillliet et al. (1994); Merriwether et al. (1995); Merriwether and Ferrell (1996) | |

| Guarani (249) | 77 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 2 | Tupi | 23° 6′ S; 55° 12′ W | Silva Jr et al. (2003); Marrero et al. (2007); García and Demarchi (2009) | |

| Pilagá (41) | 5 | 37 | 27 | 29 | 2 | Mataco-Guaicuru | 24° S; 59° W | Demarchi et al. (2001); Cabana et al. (2006) | |

| Coya (60) | 13 | 57 | 23 | 5 | 2 | Coya | 25° 30′ S; 67° 28′ W | Álvarez-Iglesias et al. (2007) | |

| Toba (80) | 15 | 43 | 5 | 37 | 0 | Mataco-Guaicuru | 26° S; 58° W | Bianchi et al. (1995); Demarchi et al. (2001); Goicoechea et al. (2001); Cabana et al. (2006) | |

| Jujuy (19) | 16 | 58 | 16 | 10 | 0 | Spanish | 27° 27′ S; 58° 59′ W | Dipierri et al. (1998) | |

| Kaingang (79) | 47 | 4 | 48 | 0 | 1 | Macro-Ge | 28° S; 51° 20′ W | Dornelles et al. (2005); Marrero et al. (2007) | |

| Mocoví (5) | 80 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | Mataco-Guaicuru | 29° 51′ S; 59° 56′ W | Tamm et al. (2007) | |

| Pehuenche (205) | 2 | 9 | 40 | 49 | 0 | Araucanian | 37° 43′ S; 71° 16′ W | Merriwether et al. (1995); Moraga et al. (1997, 2000) | |

| Mapuche (314) | 5 | 23 | 32 | 36 | 4 | Araucanian | 39° 10′–41° 20′ S; 68° 37′–70° 22′ W | Ginther et al. (1993); Horai et al. (1993); Bailliet et al. (1994); Bianchi et al. (1995); Moraga et al. (2000) | |

| Huilliche (207) | 4 | 28 | 20 | 48 | 0 | Araucanian | 41° 16′ S; 73° W | Bailliet et al. (1994); Merriwether et al. (1995); Merriwether and Ferrell (1996) | |

| Aónikenk3, 4 (15) | 0 | 0 | 27 | 73 | 0 | Chon | 45° S; 71° W | Lalueza (1995, PhD thesis, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain) | |

| Tehuelche4 (29) | 0 | 20 | 24 | 56 | 0 | Chon | 45° S; 71° W | Moraga et al. (2000) | |

| Yámana3 (Yaghan) (32) | 0 | 0 | 63 | 37 | 0 | Yámana | 47° S; 74° W | Lalueza (1995, PhD thesis); Moraga et al. (1997, 2000) | |

| Kawéskar2 (Alacaluf) (19) | 0 | 0 | 16 | 84 | 0 | Alacalufan | 49° S; 74° W | Lalueza (1995, PhD thesis) | |

| Selknam2 (Ona) (16) | 0 | 0 | 56 | 38 | 6 | Chon | 54° S; 74° W | Lalueza (1995, PhD thesis); García-Bour et al. (2004) | |

Arranged according to latitude.

Probably of non-Amerindian origin.

Ancient DNA.

Aónikenk and Tehuelche are the same tribe separated by time. Aónikenk refers to ancient DNA.

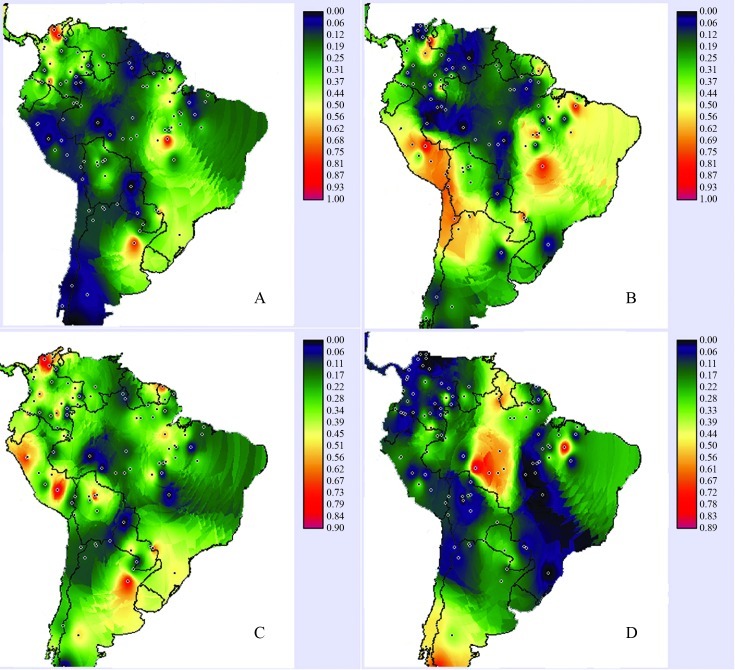

Table 6 summarizes the influence of geography. In the seven regions that were defined, 74% of the variation occurred within populations, 6% among geographic divisions and 20% among populations within divisions. To analyze this variability further, the isolated frequencies of haplogroups A to D were plotted as shown in Figure 2. High frequencies of haplogroup C were observed in specific regions along the northwestern portion of the continent, with additional high spots in southern Brazil and northern Argentina. The prevalences of haplogroups B and D showed a clear east-west separation, while for haplo-group A there were three main high prevalence nuclei in the north, center and south of the continent. Spearman’s correlation coefficient between haplogroup frequencies and latitude yielded a positive value (0.27; p < 0.01) for haplogroup A, with a corresponding negative one (−0.25; p < 0.01) for haplogroup D. The coefficients for haplo-groups B and C were not significant.

Table 6.

Mitochondrial DNA haplogroup frequencies by geography1.

| Geographic divisions | No. of populations | No. of individuals | Haplogroups (%)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | Other | |||

| Amazonia | 55 | 2410 | 20 | 21 | 31 | 25 | 3 |

| Central Plateau | 2 | 39 | 21 | 74 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Southern Brazil | 2 | 328 | 70 | 6 | 18 | 4 | 2 |

| Chaco | 6 | 479 | 10 | 43 | 22 | 24 | 1 |

| Southern South America | 3 | 726 | 4 | 20 | 31 | 43 | 2 |

| Tierra del Fuego | 5 | 111 | 0 | 5 | 39 | 55 | 1 |

| Andes | 35 | 2604 | 27 | 45 | 20 | 7 | 1 |

| Total | 108 | 6697 | |||||

AMOVA results: (a) Among geographic divisions: 6.2%; (b) Among populations within geographic divisions: 19.5%; (c) Within populations: 74.3%. The three values are statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Isoline map distribution showing the geographic pattern of the four (A–D) mtDNA haplogroups in South Amerindians. The dots indicate the locations of the populations sampled. As indicated in the scales given at right of each map, the colors represent the haplogroup frequencies, from dark blue (0.00) to red (1.00).

Table 7 summarizes the influence of language. Sixteen main language groups were considered, plus a composite set of “others”. The AMOVA results indicated that 73% of the haplogroup prevalence variability occurred within populations, with 7% of it being attributable to languages. However, there was considerable heterogeneity (20%) within the language categories established. Overall, the variability was similar to that obtained for geography.

Table 7.

Mitochondrial DNA haplogroup frequencies by language1.

| Language | No. of populations | No. of individuals | Haplogroups (%)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | Other | |||

| Tupi | 16 | 889 | 38 | 24 | 10 | 27 | 1 |

| Macro-Ge | 11 | 221 | 37 | 38 | 21 | 3 | 1 |

| Carib | 9 | 408 | 24 | 32 | 25 | 18 | 1 |

| Chibchan | 6 | 461 | 69 | 6 | 22 | 2 | 1 |

| Mataco-Guaicuru | 5 | 359 | 13 | 46 | 11 | 29 | 1 |

| Arawakan | 8 | 321 | 16 | 38 | 24 | 13 | 9 |

| Araucanian | 3 | 726 | 4 | 20 | 31 | 43 | 2 |

| Choco | 2 | 204 | 28 | 46 | 13 | 12 | 1 |

| Chon | 3 | 60 | 0 | 10 | 33 | 55 | 2 |

| Tucanoan | 6 | 140 | 14 | 26 | 48 | 8 | 4 |

| Aymaran | 2 | 427 | 4 | 76 | 9 | 10 | 1 |

| Barbacoan | 3 | 152 | 28 | 34 | 19 | 19 | 0 |

| Guahiban | 2 | 129 | 51 | 6 | 29 | 0 | 14 |

| Witotoan | 3 | 56 | 18 | 9 | 32 | 37 | 4 |

| Salivan | 2 | 41 | 29 | 7 | 32 | 27 | 5 |

| Quechuan | 6 | 497 | 14 | 51 | 23 | 11 | 1 |

| Other | 21 | 1606 | 13 | 26 | 40 | 19 | 2 |

| Total | 108 | 6697 | |||||

AMOVA results: (a) Among language groups: 6.6%; (b) Among populations within language groups: 20.1%; (c) Within populations: 73.3%. The three values are statistically significant.

Conclusion

South Amerindians have been extensively studied with regard to the Y-chromosome, as well as and especially so for mtDNA markers. In agreement with studies from other regions, by far most of the mtDNA variability (73%–74%) is intrapopulational. Geographical and linguistic factors influenced the patterns of mtDNA diversity to a similar extent, while geography was apparently more important than language in explaining the data for the Y chromosome Q clade-STRs. Additional factors that may have influenced these results include distinct male and female migration patterns, as well as cultural and other characteristics. The fact that most studies have generally dealt with small populations, in which genetic drift may be important, could also have influenced the results.

Table 2(b).

Y-Q-chromosome STR studies in distinct South Amerindian samples in which allele frequencies can be assessed (Part B).

| Ref. (n)

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STR (allele) | Mocoví (2)8 | Pacaás Novos (15)2 | Parakanã (4)2 | Pilagá (9)3 | Quechua (58)10, 11 | Ticuna (36)2 | Toba (70)3, 7 | Warao (12)2 | Wayampi (10)1 | Wayuu (14)2 | Wichí (27)3 | Yanomama (9)1 | Yukpa (12)2 | Zenu (28)2 | Total (590) |

| DYS19 (12) | 0.030 | 0.030 | 0.010 | ||||||||||||

| DYS19 (13) | 0.500 | 0.790 | 0.950 | 0.850 | 0.870 | 1.000 | 0.790 | 0.640 | 0.550 | 0.650 | 0.890 | ||||

| DYS19 (14) | 0.500 | 1.000 | 0.210 | 0.030 | 0.090 | 0.090 | 0.140 | 0.230 | 0.450 | 0.270 | 0.050 | ||||

| DYS19 (15) | 0.020 | 0.060 | 0.010 | 0.070 | 0.100 | 0.080 | 0.040 | ||||||||

| DYS19 (16) | 0.010 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS19 total | 474 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS388 (12) | 0.860 | 1.000 | 0.780 | 0.750 | 0.570 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.780 | |||||||

| DYS388 (13) | 0.140 | 0.220 | 0.250 | 0.430 | 0.500 | 0.430 | 0.200 | ||||||||

| DYS388 (14) | 0.010 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS388 (17) | 0.070 | 0.040 | |||||||||||||

| DYS388 total | 189 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS389I (12) | 0.090 | 0.080 | |||||||||||||

| DYS389I (13) | 1.000 | 0.240 | 0.800 | 0.440 | |||||||||||

| DYS389I (14) | 0.670 | 0.200 | 0.450 | ||||||||||||

| DYS389I (15) | 0.030 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS389I total | 288 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS389II (17) | 0.270 | 0.020 | |||||||||||||

| DYS389II (18) | 0.530 | 0.030 | |||||||||||||

| DYS389II (19) | 0.200 | 0.010 | |||||||||||||

| DYS389II (26) | 0.010 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS389II (27) | 0.010 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS389II (28) | 0.090 | 0.030 | |||||||||||||

| DYS389II (29) | 0.070 | 0.110 | |||||||||||||

| DYS389II (30) | 0.210 | 0.500 | 0.290 | ||||||||||||

| DYS389II (31) | 0.500 | 0.540 | 0.320 | 0.390 | |||||||||||

| DYS389II (32) | 0.500 | 0.090 | 0.160 | 0.080 | |||||||||||

| DYS389II (33) | 0.010 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS389II (34) | 0.020 | 0.010 | |||||||||||||

| DYS389II total | 288 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS390 (20) | 0.020 | 0.010 | |||||||||||||

| DYS390 (21) | 0.240 | 0.070 | |||||||||||||

| DYS390 (22) | 0.020 | 0.080 | 0.030 | 0.780 | 0.070 | ||||||||||

| DYS390 (23) | 0.500 | 0.450 | 0.210 | 0.450 | 0.060 | 0.110 | 0.080 | 1.000 | 0.220 | 0.070 | 0.250 | 0.320 | |||

| DYS390 (24) | 0.500 | 0.550 | 1.000 | 0.790 | 0.220 | 0.150 | 0.730 | 0.920 | 0.560 | 0.740 | 0.110 | 1.000 | 0.290 | 0.400 | |

| DYS390 (25) | 0.050 | 0.760 | 0.080 | 0.220 | 0.130 | 0.420 | 0.110 | ||||||||

| DYS390 (26) | 0.030 | 0.010 | |||||||||||||

| DYS390 (27) | 0.030 | 0.110 | 0.040 | 0.010 | |||||||||||

| DYS390 total | 659 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS391 (9) | 0.070 | 0.030 | 0.030 | ||||||||||||

| DYS391 (10) | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.890 | 0.840 | 0.930 | 0.900 | 0.250 | 0.570 | 0.870 | 1.000 | 0.640 | 0.800 | |||

| DYS391 (11) | 1.000 | 0.110 | 0.160 | 0.070 | 0.100 | 0.750 | 0.360 | 0.100 | 0.360 | 0.160 | |||||

| DYS391 (12) | 0.010 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS391 total | 512 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS392 (11) | 0.030 | 0.570 | 0.060 | 0.020 | |||||||||||

| DYS392 (12) | 1.000 | 0.070 | 0.130 | 0.030 | |||||||||||

| DYS392 (13) | 1.000 | 0.890 | 0.100 | 0.100 | 0.110 | 0.130 | 0.890 | 0.180 | 0.060 | 0.170 | |||||

| DYS392 (14) | 0.110 | 0.800 | 0.520 | 0.380 | 0.670 | 0.890 | 0.290 | 0.420 | 0.110 | 0.460 | 0.560 | 0.510 | |||

| DYS392 (15) | 0.100 | 0.070 | 0.620 | 0.190 | 0.070 | 0.390 | 0.360 | 0.250 | 0.150 | ||||||

| DYS392 (16) | 0.290 | 0.100 | |||||||||||||

| DYS392 (17) | 0.020 | 0.010 | |||||||||||||

| DYS392 (18) | 0.100 | 0.010 | 0.010 | ||||||||||||

| DYS392 total | 535 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS393 (11) | 1.000 | 0.040 | |||||||||||||

| DYS393 (12) | 0.060 | 0.010 | 0.100 | 0.060 | 0.040 | 0.040 | |||||||||

| DYS393 (13) | 1.000 | 0.780 | 1.000 | 0.550 | 0.710 | 0.980 | 0.750 | 0.800 | 0.840 | 0.890 | 0.500 | 0.200 | 0.670 | ||

| DYS393 (14) | 0.220 | 0.450 | 0.170 | 0.010 | 0.250 | 1.000 | 0.100 | 0.100 | 0.110 | 0.500 | 0.240 | 0.220 | |||

| DYS393 (15) | 0.030 | 0.480 | 0.020 | ||||||||||||

| DYS393 (16) | 0.030 | 0.040 | 0.010 | ||||||||||||

| DYS393 total | 584 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS437 (8) | 0.420 | 0.360 | 1.000 | 0.200 | |||||||||||

| DYS437 (9) | 0.580 | 0.030 | 0.040 | ||||||||||||

| DYS437 (11) | 0.010 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS437 (14) | 1.000 | 0.500 | 0.700 | ||||||||||||

| DYS437 (15) | 0.110 | 0.050 | |||||||||||||

| DYS437 total | 322 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS438 (9) | 0.020 | 0.010 | |||||||||||||

| DYS438 (10) | 0.050 | 0.160 | 0.050 | ||||||||||||

| DYS438 (11) | 0.790 | 0.930 | 0.850 | 0.840 | 0.850 | ||||||||||

| DYS438 (12) | 0.210 | 0.050 | 0.100 | 0.080 | |||||||||||

| DYS438 (16) | 0.010 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS438 total | 322 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS439 (9) | 0.010 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS439 (10) | 0.010 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS439 (11) | 0.090 | 0.130 | 0.230 | 0.140 | |||||||||||

| DYS439 (12) | 0.320 | 0.240 | 0.500 | 0.710 | 0.400 | ||||||||||

| DYS439 (13) | 0.680 | 0.500 | 0.290 | 0.060 | 0.330 | ||||||||||

| DYS439 (14) | 0.170 | 0.080 | 0.110 | ||||||||||||

| DYS439 total | 322 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS448 (18) | 0.010 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS448 (19) | 0.140 | 0.020 | 0.090 | ||||||||||||

| DYS448 (20) | 0.550 | 0.930 | 0.740 | ||||||||||||

| DYS448 (21) | 0.240 | 0.050 | 0.140 | ||||||||||||

| DYS448 (22) | 0.070 | 0.020 | |||||||||||||

| DYS448 total | 169 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS456 (11) | 0.010 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS456 (13) | 0.020 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS456 (14) | 0.230 | 0.020 | 0.090 | ||||||||||||

| DYS456 (15) | 0.720 | 0.730 | 0.750 | ||||||||||||

| DYS456 (16) | 0.050 | 0.250 | 0.120 | ||||||||||||

| DYS456 (17) | 0.010 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS456 total | 169 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS458 (13) | 0.020 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS458 (15) | 0.030 | 0.040 | 0.040 | ||||||||||||

| DYS458 (16) | 0.360 | 0.180 | 0.380 | ||||||||||||

| DYS458 (17) | 0.520 | 0.550 | 0.410 | ||||||||||||

| DYS458 (18) | 0.090 | 0.230 | 0.140 | ||||||||||||

| DYS458 (19) | 0.010 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS458 total | 169 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS635 (22) | 0.950 | 0.950 | 0.890 | ||||||||||||

| DYS635 (23) | 0.020 | 0.050 | 0.090 | ||||||||||||

| DYS635 (24) | 0.030 | 0.010 | |||||||||||||

| DYS635 (26) | 0.010 | ||||||||||||||

| DYS635 total | 169 | ||||||||||||||

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Programa de Apoio a Núcleos de Excelência (FAPERGS/PRONEX). We thank Sidia M. Callegari-Jacques and Luciana Tovo-Rodrigues for their help with early aspects of the statistical analyses.

Footnotes

Associate Editor: Mara H. Hutz

References

- Altuna ME, Modesti NM, Demarchi DA. Y-chromosomal evidence for a founder effect in Mbyá-guaraní Amerindians from northeast Argentina. Hum Biol. 2006;78:635–639. doi: 10.1353/hub.2007.0000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Iglesias V, Jaime JC, Carracedo A, Salas A. Coding region mitochondrial DNA SNPs: Targeting East Asian and Native American haplogroups. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2007;1:44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves-Silva J, da Silva Santos M, Guimarães PE, Ferreira AC, Bandelt HJ, Pena SD, Prado VF. The ancestry of Brazilian mtDNA lineages. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:444–461. doi: 10.1086/303004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailliet G, Rothhammer F, Carnese FR, Bravi CM, Bianchi NO. Founder mitochondrial haplotypes in Amerindian populations. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;54:27–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailliet G, Ramallo V, Muzzio M, García A, Santos MR, Alfaro EL, Dipierri JE, Salceda S, Carnese FR, Bravi CM, et al. Brief communication: Restricted geographic distribution for Y-Q* paragroup in South America. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2009;140:578–582. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri C, Heggarty P, Castrì L, Luiselli D, Pettener D. Mitochondrial DNA variability in the Titicaca basin: Matches and mismatches with linguistics and ethnohistory. Am J Hum Biol. 2011;23:89–99. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.21107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bert F, Corella A, Gené M, Pérez-Pérez A, Turbón D. Major mitochondrial DNA haplotype heterogeneity in highland and lowland Amerindian populations from Bolivia. Hum Biol. 2001;73:1–16. doi: 10.1353/hub.2001.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bert F, Corella A, Gene M, Pérez-Pérez A, Turbón D. Mitochondrial DNA diversity in the Llanos de Moxos: Moxo, Movima and Yuracare Amerindian populations. Ann Hum Biol. 2004;31:9–28. doi: 10.1080/03014460310001616464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi NO, Bailliet G, Bravi CM. Peopling of the Americas as inferred through the analysis of mitochondrial DNA. Braz J Genet. 1995;18:161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi NO, Catanesi CI, Bailliet G, Martínez-Marignac VL, Bravi CM, Vidal-Rioja LB, Herrera RJ, López-Camelo JS. Characterization of ancestral and derived Y-chromosome haplotypes of New World native populations. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1862–1871. doi: 10.1086/302141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisso-Machado R, Jota MS, Ramallo V, Paixão-Côrtes VR, Lacerda DR, Salzano FM, Bonatto SL, Santos FR, Bortolini MC. Distribution of Y-chromosome Q lineages in Native Americans. Am J Hum Biol. 2011;23:563–566. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.21173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Verea A, Jaime JC, Brión M, Carracedo A. Y-chromosome lineages in native South American populations. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2010;4:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonatto SL, Salzano FM. A single and early migration for the peopling of the Americas supported by mitochondrial DNA sequence data. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1866–1871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolini MC, Da Silva Junior WA, De Guerra DC, Remonatto G, Mirandola R, Hutz MH, Weimer TA, Silva MC, Zago MA, Salzano FM. African-derived South American populations: A history of symmetrical and asymmetrical matings according to sex revealed by bi- and uni-parental genetic markers. Am J Hum Biol. 1999;11:551–563. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6300(1999)11:4<551::AID-AJHB15>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolini MC, Salzano FM, Bau CHD, Layrisse Z, Petzl-Erler ML, Tsuneto LT, Hill K, Hurtado AM, Castro-de-Guerra D, Bedoya G, et al. Y-chromosome biallelic polymorphisms and Native American population structure. Ann Hum Genet. 2002;66:255–259. doi: 10.1017/S0003480002001148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolini MC, Salzano FM, Thomas MG, Stuart S, Nasanen SPK, Bau CHD, Hutz MH, Layrisse Z, Petzl-Erler ML, Tsuneto LT, et al. Y-Chromosome evidence for differing ancient demographic histories in the Americas. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:524–539. doi: 10.1086/377588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravi CM, Cejas S, Bailliet G, Goicoechea AS, Carnese FR, Bianchi NO. Abstracts do XXVI Congreso Argentino de Genética. San Carlos de Bariloche: 1995. Haplotipos mitocondriales en Amerindios; p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Cabana GS, Merriwether DA, Hunley K, Demarchi DA. Is the genetic structure of Gran Chaco populations unique? Interregional perspectives on Native South American mitochondrial DNA variation. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2006;131:108–119. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho-Silva DR, Santos FR, Hutz MH, Salzano FM, Pena SDJ. Divergent human Y-chromosome microsatellite evolution rates. J Mol Evol. 1999;49:204–214. doi: 10.1007/pl00006543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho-Silva DR, Santos FR, Rocha J, Pena SD. The phylogeography of Brazilian Y-chromosome lineages. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:281–286. doi: 10.1086/316931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corella A, Bert F, Pérez-Pérez A, Gené M, Turbón D. Mitochondrial DNA diversity of the Amerindian populations living in the Andean Piedmont of Bolivia: Chimane, Moseten, Aymara and Quechua. Ann Hum Biol. 2007;34:34–55. doi: 10.1080/03014460601075819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford MH. The Origins of Native Americans Evidence from Anthropological Genetics. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1998. p. 308. [Google Scholar]

- Demarchi DA, Mitchell RJ. Genetic structure and gene flow in Gran Chaco populations of Argentina: Evidence from Y-Chromosome markers. Hum Biol. 2004;76:413–429. doi: 10.1353/hub.2004.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarchi DA, Panzetta-Dutari GM, Colantonio SE, Marcellino AJ. Absence of the 9-bp deletion of mitochondrial DNA in pre-Hispanic inhabitants of Argentina. Hum Biol. 2001;73:575–582. doi: 10.1353/hub.2001.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipierri JE, Alfaro E, Martínez-Marignac VL, Bailliet G, Bravi CM, Cejas S, Bianchi NO. Paternal directional mating in two Amerindian subpopulations located at different altitudes in northwestern Argentina. Hum Biol. 1998;70:1001–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornelles CL, Battilana J, Fagundes NJ, Freitas LB, Bonatto SL, Salzano FM. Mitochondrial DNA and Alu insertions in a genetically peculiar population: The Ayoreo. Am J Hum Biol. 2004;16:479–488. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornelles CL, Bonatto SL, Freitas LB, Salzano FM. Is haplogroup X present in extant South American Indians? Am J Phys Anthropol. 2005;127:439–448. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman JR. IDRISI 15.0: The Andes edition. Clark University; Worcester: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Easton RD, Merriwether DA, Crews DE, Ferrell RE. mtDNA variation in the Yanomami: Evidence for additional New World founding lineages. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:213–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L, Lischer HE. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: A new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour. 2010;10:564–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L, Smouse PE, Quattro JM. Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among DNA haplotypes: Application to human mitochondrial DNA restriction data. Genetics. 1992;131:479–491. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.2.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagundes NJR, Kanitz R, Eckert R, Valls ACS, Bogo MR, Salzano FM, Smith DG, Silva WA, Jr, Zago MA, Ribeiro-dos-Santos AK, et al. Mitochondrial population genomics supports a single pre-Clovis origin with a coastal route for the peopling of the Americas. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:583–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehren-Schmitz L, Reindel M, Cagigao ET, Hummel S, Herrmann B. Pre-Columbian population dynamics in coastal southern Peru: A diachronic investigation of mtDNA patterns in the Palpa region by ancient DNA analysis. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2010;141:208–221. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehren-Schmitz L, Warnberg O, Reindel M, Seidenberg V, Tomasto-Cagigao E, Isla-Cuadrado J, Hummel S, Herrmann B. Diachronic investigations of mitochondrial and Y-chromosomal genetic markers in pre-Columbian Andean highlanders from South Peru. Ann Hum Genet. 2011;75:266–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2010.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuselli S, Tarazona-Santos S, Dupanloup I, Soto A, Luiselli D, Pettener D. Mitochondrial DNA diversity in South America and the genetic history of Andean Highlanders. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:1682–1691. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García A, Demarchi DA. Incidence and distribution of Native American mtDNA haplogroups in central Argentina. Hum Biol. 2009;81:59–69. doi: 10.3378/027.081.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García F, Moraga M, Vera S, Henríquez H, Llop E, Aspillaga E, Rothhammer F. mtDNA microevolution in Southern Chile’s archipelagos. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2006;129:473–481. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Bour J, Pérez-Pérez A, Álvarez S, Fernández E, López-Parra AM, Arroyo-Pardo E, Turbón D. Early population differentiation in extinct aborigines from Tierra Del Fuego – Patagonia: Ancient mtDNA sequences and Y-chromosome STR characterization. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2004;123:361–370. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayà-Vidal M, Moral P, Saenz-Ruales N, Gerbault P, Tonasso L, Villena M, Vasquez R, Bravi CM, Dugoujon JM. mtDNA and Y-chromosome diversity in Aymaras and Quechuas from Bolivia: Different stories and special genetic traits of the Andean Altiplano populations. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2011;145:215–230. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geppert M, Baeta M, Núñez C, Martínez-Jarreta B, Zweynert S, Cruz OW, González-Andrade F, González-Solorzano J, Nagy M, Roewer L. Hierarchical Y-SNP assay to study the hidden diversity and phylogenetic relationship of native populations in South America. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2011;5:100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginther C, Corach D, Penacino GA, Rey JA, Carnese FR, Hutz MH, Anderson A, Just J, Salzano FM, King M-C. Genetic variation among the Mapuche Indians from the Patagonian region of Argentina: Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation and allele frequencies of several nuclear genes. In: Pena SDJ, Chakraborty R, Epplen JT, Jeffreys AJ, editors. DNA Fingerprinting: State of the Science Birkhäuser Verlag. Berlin: 1993. pp. 211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goicoechea AS, Carnese FR, Dejean C, Avena SA, Weimer TA, Estalote AC, Simões ML, Palatnik M, Salamoni SP, Salzano FM, et al. New genetic data on Amerindians from the Paraguayan Chaco. Am J Hum Biol. 2001;13:660–667. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horai S, Kondo S, Nakagawa-Hattori Y, Hayashi S, Sonoda S, Tajima K. Peopling of the Americas, founded by four major lineages of mitochondrial DNA. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10:23–47. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a039987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunley KL, Cabana GS, Merriwether DA, Long JC. A formal test of linguistic and genetic coevolution in native Central and South America. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2007;132:622–631. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingman M, Kaessmann H, Pääbo S, Gyllensten U. Mitochondrial genome variation and the origin of modern humans. Nature. 2000;408:708–713. doi: 10.1038/35047064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jota MS, Lacerda DR, Sandoval JR, Vieira PPR, Santos-Lopes SS, Bisso-Machado R, Paixão-Cortes VR, Revollo S, Pazy-Miño C, Fujita R, et al. A new subhaplogroup of Native American Y chromosomes from the Andes. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2011;146:553–559. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karafet T, Segura SL, Vuturo-Brady J, Posukh O, Osipova L, Wiebe V, Romero F, Long JC, Harihara S, Jin F, et al. Y chromosome markers and trans-Bering Strait dispersals. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1997;102:301–314. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199703)102:3<301::AID-AJPA1>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karafet TM, Zegura SL, Posukh O, Osipova L, Bergen A, Long J, Goldman D, Klitz W, Harihara S, de Knijff P, et al. Ancestral Asian source(s) of New World Y-chromosome founder haplotypes. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:817–831. doi: 10.1086/302282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karafet TM, Mendez FL, Meilerman MB, Underhill PA, Zegura SL, Hammer MF. New binary polymorphisms reshape and increase resolution of the human Y chromosomal haplogroup tree. Genome Res. 2008;18:830–838. doi: 10.1101/gr.7172008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyeux G, Rodas C, Gelvez N, Carter D. Possible migration routes into South America deduced from mitochondrial DNA studies in Colombian Amerindian populations. Hum Biol. 2002;74:211–233. doi: 10.1353/hub.2002.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivisild T, Shen P, Wall D, Do B, Sung R, Davis K, Passarino G, Underhill PA, Scharfe C, Torroni A, et al. The role of selection in the evolution of human mitochondrial genomes. Genetics. 2006;172:373–387. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.043901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite FP, Callegari-Jacques SM, Carvalho BA, Kommers T, Matte CH, Raimann PE, Schwengber SP, Sortica VA, Tsuneto LT, Petzl-Erler ML, et al. Y-STR analysis in Brazilian and South Amerindian populations. Am J Hum Biol. 2008;20:359–363. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lell JT, Sukernik RI, Starikovskaya YB, Su B, Jin L, Schurr TG, Underhill PA, Wallace DC. The dual origin and Siberian affinities of Native American Y chromosomes. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:192–206. doi: 10.1086/338457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CM, Jr, Tito RY, Lizárraga B, Stone AC. Land, language, and loci: mtDNA in Native Americans and the genetic history of Peru. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2005;127:351–360. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CM, Jr, Buikstra JE, Stone AC. Ancient DNA and genetic continuity in the South Central Andes. Lat Am Antiq. 2007;18:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lobato-da-Silva DF, Ribeiro-dos-Santos AKC, Santos SEB. Diversidade genética de populações humanas na Amazônia. In: Guimarães Vieira IC, Cardoso da Silva JM, Oren DC, D’Ineao MA, editors. Diversidade Humana e Cultural na Amazônia. Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi; Belém: 2001. pp. 167–193. [Google Scholar]

- Marrero AR, Silva-Junior WA, Bravi CM, Hutz MH, Petzl-Erler ML, Ruiz-Linares A, Salzano FM, Bortolini MC. Demographic and evolutionary trajectories of the Guarani and Kaingang natives of Brazil. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2007;132:301–310. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazières S, Guitard E, Crubézy E, Dugoujon JM, Bortolini MC, Bonatto SL, Hutz MH, Bois E, Tiouka F, Larrouy G, et al. Uniparental (mtDNA, Y-chromosome) polymorphisms in French Guiana and two related populations – Implications for the region’s colonization. Ann Hum Genet. 2008;72:145–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton PE, Briceño I, Gómez A, Devor EJ, Bernal JE, Crawford MH. Biological relationship between Central and South American Chibchan speaking populations: Evidence from mtDNA. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2007;133:753–770. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes-Junior CT, Simões AL. Mitochondrial DNA variability among eight Tikúna villages: Evidence for an intratribal genetic heterogeneity pattern. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2009;140:526–531. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriwether DA, Ferrell RE. The four founding lineage hypothesis for the New World: A critical reevaluation. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1996;5:241–246. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1996.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriwether DA, Rothhammer F, Ferrell RE. Genetic variation in the New World: Ancient teeth, bone, and tissue as sources of DNA. Experientia. 1994;50:592–601. doi: 10.1007/BF01921730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriwether DA, Rothhammer F, Ferrell RE. Distribution of the four founding lineage haplotypes in Native Americans suggests a single wave of migration for the New World. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1995;98:411–430. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330980404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriwether DA, Kemp BM, Crews DE, Neel JV. Gene flow and genetic variation in the Yanomama as revealed by mitochondrial DNA. In: Renfrew C, editor. America Past, America Present: Genes and Languages in the Americas and Beyond Oxbow books. Oxford: 2000. pp. 89–124. [Google Scholar]

- Mesa NR, Mondragón MC, Soto ID, Parra MV, Duque C, Ortíz-Barrientos D, García LF, Velez ID, Bravo ML, Múnera JG, et al. Autosomal, mtDNA, and Y-chromosome diversity in Amerindians: Pre- and post-Columbian patterns of gene flow in South America. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:1277–1286. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9297(07)62955-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsalve MV, Groot de Restrepo H, Espinel A, Correal G, Devine DV. Evidence of mitochondrial DNA diversity in South American aboriginals. Ann Hum Genet. 1994;58:265–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1994.tb01890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraga M, Rothhammer F, Carvallo P. Barton SA, Rothhammer F, Schull WS, editors. Mitochondrial DNA variation in aboriginal populations of southern Chile. Patterns of Morbidity in Andean Aboriginal Populations: 8,000 Years of Evolution Amphora Editora, Santiago. 1997. pp. 32–36.

- Moraga ML, Rocco P, Miquel JF, Nervi F, Llop E, Chakraborty R, Rothhammer F, Carvallo P. Mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms in Chilean aboriginal populations: Implications for the peopling of the southern cone of the continent. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2000;113:19–29. doi: 10.1002/1096-8644(200009)113:1<19::AID-AJPA3>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraga M, Santoro CM, Standen VG, Carvallo P, Rothhammer F. Microevolution in prehistoric Andean populations: Chronologic mtDNA variation in the desert valleys of northern Chile. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2005;127:170–181. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena S, Santos FR, Bianchi NO, Bravi CM, Carnese RF, Rothhammer F, Gerelsaikhan T, Munkhtuja B, Oyunsuren T. A major founder Y-chromosome haplotype in Amerindians. Nat Genet. 1995;11:15–16. doi: 10.1038/ng0995-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perego UA, Achilli A, Angerhofer N, Accetturo M, Pala M, Olivieri A, Kashani BH, Ritchie KH, Scozzari R, Kong Q-P, et al. Distinctive Paleo-Indian migration routes from Beringia marked by two rare mtDNA haplogroups. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perego UA, Angerhofer N, Pala M, Olivieri A, Lancioni H, Kashani BH, Carossa V, Ekins JE, Gómez-Carballa A, Huber G, et al. The initial peopling of the Americas: A growing number of founding mitochondrial genomes from Beringia. Genome Res. 2010;20:1174–1179. doi: 10.1101/gr.109231.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro-dos-Santos AKC, Guerreiro JF, Santos SEB, Zago MA. The split of the Arara population: Comparison of genetic drift and founder effect. Hum Hered. 2001;51:79–84. doi: 10.1159/000022962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickards O, Martinez-Labarga C, Lum JK, De Stefano GF, Cann RL. mtDNA history of the Cayapa Amerinds of Ecuador: Detection of additional founding lineages for the native American populations. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:519–530. doi: 10.1086/302513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Delfin L, Santos SEB, Zago MA. Diversity of the human Y chromosome of South American Amerindians: A comparison with Blacks, Whites and Japanese from Brazil. Ann Hum Genet. 1997;61:439–448. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.1997.6150439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]