Abstract

The eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase (eEF-2K) modulates the rate of protein synthesis by impeding the elongation phase of translation by inactivating the eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF-2) via phosphorylation. eEF-2K is known to be activated by calcium and calmodulin, whereas the mTOR and MAPK pathways are suggested to negatively regulate kinase activity. Despite its pivotal role in translation regulation and potential role in tumor survival, the structure, function and regulation of eEF-2K have not been described in detail. This deficiency may result from the difficulty of obtaining the recombinant kinase in a form suitable for biochemical analysis. Here we report the purification and characterization of recombinant human eEF-2K expressed in the Escherichia coli strain Rosetta-gami 2(DE3). Successive chromatography steps utilizing Ni-NTA affinity, anion-exchange and gel filtration columns accomplished purification. Cleavage of the thioredoxin-His6-tag from the N-terminus of the expressed kinase with TEV protease yielded 9 mg of recombinant (G-D-I)-eEF-2K per liter of culture. Light scattering shows that eEF-2K is a monomer of ~ 85 kDa. In vitro kinetic analysis confirmed that recombinant human eEF-2K is able to phosphorylate wheat germ eEF-2 with kinetic parameters comparable to the mammalian enzyme.

Keywords: Elongation factor 2 kinase, eEF-2K, calmodulin

INTRODUCTION

Protein synthesis is an exquisitely controlled process that involves several initiation, elongation and termination factors [1-4]. The human elongation factor 2 kinase (eEF-2K) plays a major role in the regulation of protein synthesis. This kinase impedes the elongation phase of translation, thus impeding the rate at which proteins are synthesized. It accomplishes this by inactivating its only known substrate elongation factor 2 (eEF-2), by phosphorylation of Thr-56 [5-9]. eEF-2 is responsible for the ribosomal translocation of the nascent peptide chain from the A-site to the P-site during translation [10-12].

eEF-2K is classified as a Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase (CaMK-III) [5, 8, 13, 14] because it requires Ca2+ and calmodulin (CaM) for autophosphorylation. Autophosphorylation of eEF-2K has been shown to activate the kinase and impart significant Ca2+-independent activity [13, 14].

Apart from it being a Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase, eEF-2K is a representative of a unique family of enzymes known as atypical protein kinases because they lack sequence homology with conventional protein kinases [16, 17]. Comparison studies between the atypical channel kinase 1 (CHAK1 or TRPM7) and the conventional cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) showed that despite the lack of sequence similarity, the catalytic domain structure of the atypical protein kinase is homologous with the classical conventional kinase – two lobes separated by a catalytic cleft [18, 19]. Sequence alignment studies as well as mutational analysis of eEF-2K suggest that its catalytic domain appears to be located towards the N-terminus, roughly between residues 110 and 330 [20, 21]. A Ca2+/CaM binding site (around residues 80-100) has been proposed to just precede the kinase domain [20, 21]. C-terminal deletion mutantslose their ability to bind eEF-2. This implies that additional protein-protein interactions outside the catalytic domain between residues 551 and 725 are essential for eEF-2 recognition [20, 21].

In addition to its activation by Ca2+/CaM, other factors modulate the functioning of eEF-2K. Via multisite phosphorylation of eEF-2K, two central signaling pathways are involved in negatively regulating the activity of the kinase – the mTOR and the MAPK (MEK/ERK) cascades [22]. On the other hand, two kinases have been shown to activate eEF-2K through phosphorylation – the cAMP-dependent PKA and the energy-supply regulator AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [23-25]. No mechanistic basis for these intriguing observations has yet been described, and undoubtedly more detailed enzymology will be required to understand them.

Intriguingly, eEF-2K has been recently implicated in enhancing tumor survival [26-30]. In glioblastoma cells, the kinase has been shown to regulate autophagy – a pro-survival pathway stimulated in response to nutrient deficiency and cell stress [29-31]. Additionally, metastatic breast cancer cells appear to up-regulate the activity of the kinase in response to treatment with chemotherapeutic agents, in the process inducing autophagy and resistance against anti-tumorous agents [32, 33]. These findings suggest that eEF-2K may be a target for anti-cancer therapy.

To date there has been no report of the purification of recombinant human eEF-2K from bacteria in a tag-free form. This study is the first report of the purification of milligram amounts of recombinant human eEF-2K expressed in Escherichia coli that meets a standard fit for rigorous biochemical studies. Characterization studies confirm the existence of the kinase as a monomer that is able to phosphorylate wheat germ eEF-2 to an extent comparable to that of the kinase purified from a mammalian source.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents, Strains, Plasmids and Equipment

Yeast extract, tryptone and agar were purchased from USB Corporation (Cleveland, OH). Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and dithiothreitol (DTT) were obtained from US Biological (Swampscott, MA). Qiagen (Valencia, CA) supplied Ni-NTA Agarose, QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit, QIA quick PCR Purification Kit and QIA quick Gel Extraction Kit. Restriction enzymes, PCR reagents and T4 DNA Ligase were obtained from either New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA) or Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA). Oligonucleotides for DNA amplification and mutagenesis were from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA). Stratagene PfuUltra™ High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase was purchased from Agilent Technologies, Inc. (Santa Clara, CA). BenchMark™ Protein Ladder was from Invitrogen Corporation. SIGMA FAST™ Protease inhibitor cocktail tablets for purification of His-tagged proteins, ultra-pure grade Tris-HCl, HEPES and calmodulin were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All other buffer components or chemicals were purchased from either Sigma-Aldrich or Fischer Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Amicon Ultrafiltration Stirred Cells, Ultracel Amicon Ultrafiltration Discs and Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filter Units were from Millipore (Billerica, MA). MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH) supplied [γ-32P]ATP.

Escherichia coli strain DH5α– for cloning – was obtained from Invitrogen Corporation, and BL21 (DE3) and Rosetta-gami™ 2(DE3)– for recombinant protein expression – were from Novagen, EMD4 Biosciences (Gibbstown, NJ). The pET-32a vector was obtained from Novagen. Wheat germ eEF-2 was a generous gift from Dr. Karen Browning, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX.

The ÄKTA FPLC™ System and the following columns – HiPrep™ 26/60 Sephacryl™ S-200 HR gel filtration column, Mono Q HR 10/10 anion exchange column and HiLoad™ 16/60 Superdex™ 200 prep grade gel filtration column – were from Amersham Biosciences/ GE Healthcare Life Sciences (Piscataway, NJ). Absorbance readings were performed on a Cary 50 UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Radioactivity measurements were performed on either a Packard 1500 Lab TriCarb Liquid Scintillation Analyzer or a Wallac MicroBeta® TriLux Scintillation Counter from PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA). Proteins were resolved by Tris-glycine sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), under denaturing conditions on 10% gels, using the Mini-PROTEAN 3 vertical gel electrophoresis apparatus from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). A Techne Genius Thermal Cycler purchased from Techne, Inc. (Burlington, NJ) was used for PCR.

1. Molecular Biology

p32eEF-2K – cDNA from the bacterial expression vector pGEX-2T, encoding the human GST-tagged eEF-2K (GenBank accession number NM_013302), was used as a template in a PCR reaction. To clone the human eEF-2K cDNA, the desired sequence was amplified by PCR using a specifically designed forward primer, 5’-GGATATCATGGCAGACGAAGATCTCATCTTCCGCCTGG -3’ (EcoRV recognition site underlined) and reverse primer 5’-CGGCTCGAGTTA CTC CTC CAT CTG GGC CCA GGC CTC TTC AG -3’ (XhoI recognition site underlined), and ligated into the pET-32a vector. The pET-32a expression vector, which facilitates protein expression under the control of the T7 promoter, encodes for a thioredoxin tag (Trx-tag) to increase protein solubility, a hexa-histidine tag (His6-tag) to allow for Ni-affinity chromatography purification, and an enterokinase protease recognition sequence that is N-terminal to the protein of interest and permits cleavage from the fusion protein tag. The PCR amplification reaction mixture (50 μL) contained 1X PfuUltra™ HF reaction buffer (Tris (pH 8.0) and 2 mM Mg2+), 200 μM of each dNTP, 0.2 μM each of the forward and reverse primer, 10 ng of DNA template and1U of PfuUltra™ HF polymerase. The PCR cycle conditions included initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, primer annealing at 57°C for 1 min and extension at 72°C for 5 min, with a final elongation step of 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR product was digested with the restriction enzymes EcoRV and XhoI, and ligated into an EcoRV-XhoI digested pET-32a vector to give the final p32eEF-2K construct, which was then transformed into the E. coli strain DH5α. Plasmid DNA was purified, and the sequence then verified by sequencing at the ICMB Core Facilities, UT Austin, using an Applied Biosystems automated DNA sequencer.

p32TeEF-2K – To facilitate cleavage of the Trx-His6-tag from recombinant eEF-2K, the sequence coding for the enterokinase (EK) cleavage site (DDDDK) in pET-32a was replaced by one coding for the Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease cleavage recognition sequence (ENLYFQGDI), to generate p32TeEF-2K (Figure 1A and 1B). An oligonucleotide 5’-C GAA AAC CTG TAT TTT CAG GGA GAT -3’ and its reverse complement 5’-CATGG CTT TTG GAC ATA AAA GTC CCT CTA -3’ were designed to match a KpnI-EcoRV digested plasmid, and included a sequence coding for the TEV protease cleavage recognition site sandwiched between the KpnI (underlined) and EcoRV (italicized) recognition sites. Both oligonucleotides were mixed in equimolar amounts, heated to 95°C for 5 min and cooled to allow annealing in order to obtain a double stranded DNA fragment with blunt and sticky ends. This fragment was then ligated into the p32eEF-2K construct digested with KpnI and EcoRV. The ligation product was transformed into DH5α cells, the p32TeEF-2K construct purified, and the sequence then verified at the ICMB Core Facilities.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of cloning and expression strategy for eEF-2K.

(A) Strategy for eEF-2K cloning into the pET-32a vector, including the replacement of EK (Enterokinase) with TEV (Tobacco Etch Virus) protease cleavage site. (B) Schematic representation of the expression product of eEF-2K from the pET-32a vector. (C) Primary amino acid sequence of the tagless recombinant kinase, (G-D-I)-eEF-2K. Composition of purified eEF-2K was analyzed for consistency with the known primary amino acid sequence by amino acid analysis as described under ‘Materials and Methods’.

2. Expression and Purification of eEF-2K

Expression of eEF-2K – Recombinant human eEF-2K was expressed in the E. coli strain Rosetta-gami™ 2(DE3) (Novagen) using the p32TeEF-2K expression vector. Out of a total of 725 residues, eEF-2K contains 63 rare codons (8.7%), and hence it was decided to use the Rosetta-gami 2(DE3) strain which carries the pRARE2 plasmid (supplies tRNAs for seven rare codons) and can potentially alleviate codon bias when expressing human proteins. A single colony of freshly transformed cells was used to inoculate 100 mL of LB media containing 135 μM ampicillin, 300 μM chloramphenicol and 20 μM tetracycline, and grown overnight at 37°C on a shaker (250 rpm). The culture was diluted 50-fold into LB media containing the same concentration of antibiotics and incubated at 37 °C on a shaker (250 rpm) for about 5-6 h until it reached an OD600 of 0.8. Protein expression was then induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 16 h at 22°C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (6000g for 10 min at 4 °C), flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C.

Ni-NTA affinity chromatography – The bacterial pellet (~3.5 g wet cells from 1L of culture) was thawed on ice and resuspended in 100 mL of Buffer A (20 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.5 M NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 1% triton X-100 (v/v), 0.03% brij 30 (v/v), 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol (v/v), 0.1 mM tosyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK), 1% protease inhibitor cocktail for His-tagged proteins (Sigma) (v/v) and 7 μM lysozyme). The suspension was sonicated twice for 5 min (5 s pulses) with an interval of 5 min. The temperature was monitored during the sonication using a thermal probe, and maintained between 4-6°C. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation (Sorvall – SS34 rotor) at 27,000g for 30 min at 4 °C and the supernatant gently agitated with 5 mL of Ni-NTA beads (Qiagen) for 1 h at 4 °C. In a 100 mL chromatography column, the beads were washed with 150 mL of Buffer B (20 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM imidazole, 0.03% brij 30 (v/v), 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol (v/v), 0.1 mM TPCK and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (v/v)). The Trx-His6-TEV-eEF-2K was then eluted with 30 mL of Buffer C (20 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 250 mM imidazole, 0.03% brij 30 (v/v), 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol (v/v), 0.1 mM TPCK and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (v/v)).

26/60 Sephacryl S-200 gel filtration chromatography – The protein eluted from the Ni-NTA column was concentrated to a volume of 10 mL using a 50 mL Amicon Ultrafiltration Stirred Cell 8050 having a YM-10 Ultracel Amicon Ultrafiltration Disc (Millipore, NMWL: 10,000), filtered and applied to a HiPrep™ 26/60 Sephacryl™ S-200 HR gel filtration column pre-equilibrated with Buffer D (50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 0.15 M NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2 and 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol (v/v)). Chromatography was performed over one column volume (320 mL) at a flow rate of 2 mL/min. The collected fractions were analyzed for purity by resolving the samples by SDS-PAGE. Fractions that contained the eluted kinase were pooled.

Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease cleavage of Trx-His6-TEV-eEF-2K – The Trx-His6-tagged eEF-2K sample pooled after the Sephacryl S-200 gel filtration chromatography step was subjected to TEV protease cleavage. The concentration of eEF-2K was determined (see below), and the reaction was carried out in Buffer D (pH 8.0) by the addition of 1.5% TEV protease(w/w). Cleavage was performed at 30°C for 2 h while shaking gently. The extent of cleavage of the tag was estimated by SDS-PAGE.

Mono Q 10/10 anion exchange chromatography – After cleavage, the protein was filtered and applied to a Mono Q HR 10/10 anion exchange column pre-equilibrated with Buffer E (25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 0.15 M NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.03% brij 30 (v/v) and 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol (v/v)). The column was developed with a gradient of 0.15-1.0 M NaCl in Buffer E over 17 column volumes at a flow rate of 3 mL/min. SDS-PAGE was used to analyze the purity of the collected fractions and those that contained the eluted cleaved eEF-2K were pooled.

16/60 Superdex 200 gel filtration chromatography – Pooled fractions from the Mono Q 10/10 chromatography step were concentrated to a volume of 4 mL using an Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Unit (Millipore) and applied to a HiLoad™ 16/60 Superdex™ 200 prep grade gel filtration column pre-equilibrated with Buffer D. Gel filtration chromatography was performed over 1.5 column volumes (180 mL) at a flow rate of 1.2 mL/min. Fractions were collected and analyzed for purity using SDS-PAGE. Fractions that contained the recombinant human eEF-2K were pooled and dialyzed against storage buffer (Buffer S1)(25 mM HEPES(pH 7.5), 2 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2 and 10% glycerol). The dialyzed protein was concentrated using a centrifugal filter unit, aliquoted, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C. The concentration of eEF-2K was determined by measuring its absorbance at 280 nm and using an extinction coefficient (A280) of 97150 cm-1M-1 calculated from the primary amino acid sequence. The purity of the enzyme was estimated after each purification step by determining its specific activity against a peptide substrate (see below) and analyzing the density of the Coomassie-stained bands observed after resolving the samples by SDS-PAGE.

Expression and purification of TEV protease – Tobacco Etch Virus protease was expressed from the pRK793 expression vector (a generous gift from Dr. John Tesmer, Life Sciences Institute, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI). The construct was transformed into Rosetta-gami™ 2(DE3) cells and protein expression induced with 0.5 mM IPTG at 28 °C for 4h before being harvested. The protein was purified according to protocols published earlier [34, 35].

Expression and purification of calmodulin– The calmodulin (CAM) clonein the pET-23 expression vector, a gift from Dr. Neal Waxham (Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy, University of Texas Medical School at Houston, Houston, TX), was transformed into BL21 (DE3) cells (Novagen) and protein expression induced with 0.5 mM IPTG at 30°C for 5 h. CaM was purified as previously described [36] with minor modifications [37].

Peptide synthesis –Apeptide, Acetyl-RKKYKFNEDTERRRFL-Amide (2,227.8 Da), was synthesized and purified at the UT Molecular Biology Core Facilities. The peptide was dissolved in 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5). The molecular weight of the peptide was estimated by MALDI mass spectrometry and the concentration of the peptide was determined either by amino acid analysis or calculation from an absorbance at 280 nm using an extinction coefficient of 1280 cm-1M-1. This peptide was derived from a positional scanning assay, used to determine preferences of a protein kinase for amino acids at positions within a peptide substrate [38].

3. Analytical Methods

Light scattering – Multi-angle laser light scattering experiments were performed on eEF-2K previously dialyzed against Buffer F (25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT and 5 mM MgCl2). A similar setup as described earlier [39] was employed, however, only a single TSK-GEL G3000PWXL size-exclusion column (TosoHaas, 300 × 7.8 mm) was used. Buffer F was used to establish the light scattering and refractive index baselines. The eEF-2K sample, 40 μL at 36 μM, was centrifuged for 30 s and injected into the column. Size exclusion chromatography was performed at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min at room temperature for a run time of ~ 40 min.

Amino acids analysis – Analysis was performed at the Protein Chemistry Laboratory, Texas A&M University. The amino acid composition of eEF-2K was determined by hydrolyzing a sample in 6 N HCl at 110 °C for 24h. The internal standards – Norvaline for primary amino acids and Sarcosine for secondary amino acids – were added prior to hydrolysis to control errors due to sample loss, injection variation and microvariations in dilution. The eEF-2K sample was analyzed on a Hewlett Packard Amino Quant System that includes automated pre-column derivatization of the hydrolyzed primary amino acids with o-phthaldehyde (OPA) and secondary amino acids with 9-fluoromethyl-chloroformate (FMOC). Derivatized amino acids were then separated by reverse phase HPLC on the HP 1090L and detected by a photodiode array (UV-DAD). The analysis was performed in triplicate.

General kinetic assays – eEF-2K activity was assayed at 30 °C in Buffer G (25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 2 mM DTT, 0.6 μM BSA, 50 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.6 μM CaM, 1.5 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM MgCl2), containing 50 μM peptide substrate (Acetyl-RKKYKFNEDTERRRFL-Amide), 2 nM eEF-2K enzyme and 0.5 mM [γ-32P]ATP (100-1000 cpm/pmol) in a final reaction volume of 50 μL. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30 °C for 5 min before the reaction was initiated by addition of 0.5 mM [γ-32P]ATP. At set time points, 5-10 μL aliquots were taken and spotted onto P81 cellulose filters (Whatman, 2×2 cm). The filter papers were then washed three times in 50 mM phosphoric acid (10 min each wash), once in acetone (10 min) and finally dried. The amount of labeled peptide associated with each paper was determined by measuring the cpm on a Packard 1500 scintillation counter.

-

Substrate dependence assays– eEF-2 dependence assays were performed using 2 nM eEF-2K and several concentrations of wheat germ eEF-2 (0-20 μM) in a buffer containing 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 2 mM DTT, 0.6 μM BSA, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 150 μM CaCl2, 2 μM CaM, 10 mM MgCl2 and 0.5 mM [γ-32P]ATP (100-1000 cpm/pmol) in a final reaction volume of 100 μL. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30 °C for 10 min before the reaction was initiated by addition of ATP. After 1 min, 10 μL aliquots were removed and the reaction quenched by addition of SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer followed by heating for 10 min at 95 °C. The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. The gels were dried, the pieces containing eEF-2 excised, and the associated radioactivity measured with a Packard 1500 liquid scintillation analyzer. Kinase activity was determined by calculating the rate of phosphorylation of eEF-2 (μM.s-1), and the data were fitted to equation 1.

(Equation 1) The parameters are defined as follows: v, initial velocity; , apparent maximum velocity; [S], concentration of varied substrate; , apparent substrate concentration required to achieve half maximal activity.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Purification of eEF-2K

Rabbit reticulocytes and rat pancreas were sources of the kinase [13, 14] prior to knowing the primary sequence of eEF-2K. Purification of eEF-2K to homogeneity involved several steps [13, 14], which would result in very low yields of the enzyme. Additionally, results reveal that multisite phosphorylation by several kinases is responsible for the regulation of eEF-2K activity in vivo [22, 24, 25, 40-42] – thus purification of the enzyme from a vertebrate source would most likely yield a protein with non-homogenous regulatory modifications. More recently, studies on the regulation of eEF-2K in vitro have been conducted using the human form of the kinase expressed as a GST-tagged fusion protein in the E. coli strain BL21(DE3), which is unstable and difficult to purify [20, 21]. There has been no report of the purification of eEF-2K from bacteria in a tag-free form. Here we discuss the purification of recombinant human eEF-2K expressed in bacteria that catalytically mimics the enzyme purified from a mammalian source (rabbit reticulocytes and rat pancreas). Having the pure recombinant tagless kinase in hand allows one to rigorously address its mechanism of regulation.

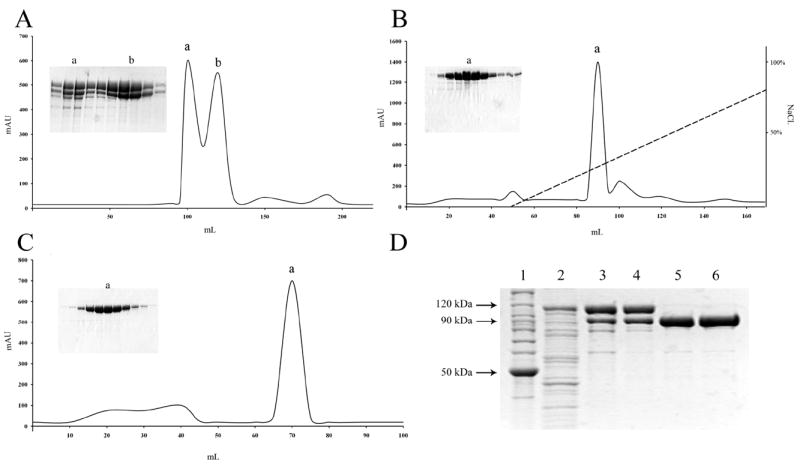

Expression of the full-length recombinant human eEF-2K was carried out from a modified pET-32a vector under the control of the T7 promoter in the bacterial Escherichia coli strain Rosetta-gami 2(DE3). Induction of protein expression with 0.5 mM IPTG for 16 h at 22 °C furnished relatively high levels of soluble Trx-His6-TEV-eEF-2K, which was purified by four sequential chromatography steps. After each of the purification steps employed, the purity of the enzyme was estimated by determining its specific activity against a peptide substrate, as well as by analyzing the density of the Coomassie-stained bands observed after resolving the samples by SDS-PAGE (Figure 2D). The purity and yield of the kinase after each purification step are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2. Purification of eEF-2K.

(A) Gel filtration chromatography on a HiPrep™ 26/60 Sephacryl S-200 column. Ni-NTA eluate was concentrated and applied to the gel filtration column. Peak (a) contains aggregated eEF-2K while peak (b) contains monomeric eEF-2K. (B) Ion exchange chromatography on a Mono Q HR 10/10 anion exchange column. Peak (b) fractions from the previous purification step were pooled and then incubated with TEV Protease, resulting in cleavage of the Trx-His-tag. Tagless-eEF-2K was applied to the Mono Q 10/10 column. (C) Gel filtration chromatography on a HiLoad™ 16/60 Superdex 200 column. Peak (a) fractions from the Mono Q column were pooled and applied to the gel filtration column. (D) Samples from the various purification steps were resolved by SDS-PAGE: BenchMark™ protein ladder (lane 1); Bacterial lysate (lane 2); Ni-NTA agarose affinity chromatography (lane 3); 26/60 Sephacryl S-200 gel filtration chromatography (lane 4); Mono Q 10/10 anion exchange chromatography following cleavage of Trx-His-tag by TEV Protease (lane 5); HiLoad™ Superdex 200 gel filtration chromatography (lane 6).

Table 1.

Summary of the purification of recombinant human eEF-2K from a 1 L culturea of the E. coli strain Rosetta-gami 2(DE3)

| Purification Step | Total proteinb (mg) | Specific activityc (nmol.min-1.mg-1) | Total activity (nmol.min-1) | Purification fold | Purityd (%) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Lysate | 525 | 108 | 57,000 | 1 | 29 | 100 |

| Ni-NTA Agarose | 55 | 283 | 15,500 | 2.6 | 89 | 27.5 |

| Sephacryl S-200 | 24 | 391 | 9,400 | 3.6 | 98 | 16.5 |

| Cleavage of Trx-His-tag with TEV Protease | ||||||

| Mono Q | 10.9 | 460 | 5,000 | 4.2 | 98 | 8.8 |

| Superdex 200 | 9.1 | 536 | 4,900 | 5 | 98 | 8.6 |

1 L of culture corresponds to ~ 3.5 g of wet cells.

Protein concentration and total amount of protein was determined by measuring its absorbance at 280 nm.

Specific activity of eEF-2K was determined by a kinase assay using 50 μM peptide substrate as described under ‘Materials and Methods’. The activity is expressed as nmol of Pi incorporated per minute per mg of protein.

Purity of eEF-2K was estimated by SDS-PAGE analysis using ImageQuant™ TL software.

A 1 L culture yielded 525 mg of soluble protein, of which 28% corresponded to the over-expressed Trx-His6-TEV-eEF-2K recombinant protein. The first purification step involved the subjection of the cleared lysate (supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail) to Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. SDS-PAGE analysis of the purified fraction revealed a 28% yield with a 2.6-fold purification of the recombinant kinase having an overall purity of 89%. To eliminate the contaminant proteins, size exclusion chromatography was performed on a 26/60 Sephacryl™ S-200 gel filtration column, which led to the elution of eEF-2K as two overlapping peaks – the first, peak (a), that was eluted around 95-110 mL and the second, peak (b), that was eluted around 110-130 mL (Figure 2A). SDS-PAGE analysis indicated that peak (a) contained a higher level of impurities compared to peak (b). In addition, estimation of the activity associated with each peak showed that the enzyme present in peak (b) possessed a four-fold higher activity than that eluted in peak (a). Thus, peak (a) was discarded while peak (b) – having an overall purity of 97% and a yield of 60% – was pooled for further purification. Gel analysis of both the Ni-NTA affinity and gel filtration purification steps showed the appearance of two prominent bands, the one with the higher molecular weight corresponded to Trx-His6-TEV-eEF-2K, and the other one to tag-less eEF-2K (as determined from the sample resolved after TEV protease cleavage) (Figure 2D). This cleavage appears to occur either before or during the Ni-NTA affinity chromatography purification step and could be the result of non-specific protease activity.

Cleavage of the Trx-His6-tag from the eEF-2K protein was achieved by incubation of the fusion protein with 1.5% TEV protease (w/w). To determine the optimum incubation time, the reaction was carried out over several time periods, of which incubation at 30 °C for 2 hours, or 4 °C for 4 hours, was deemed sufficient for complete cleavage of the Trx-His6-tagged eEF-2K. The reaction yielded recombinant human eEF-2K, preceded at its N-terminus by three additional amino acid residues (G-D-I), and the extent of cleavage of the tag was estimated by SDS-PAGE. Purification of the protein from the cleaved tag was accomplished using anion exchange chromatography on a Mono Q 10/10 column. The cleaved Trx-His6-tag was not retained by the Mono-Q 10/10 column and was washed out in the flow-through fraction. The column was developed with a gradient of 0.15-1.0 M NaCl and the (G-D-I)-eEF-2K was eluted between 390-435 mM NaCl as a major peak (a) having an overall purity of 97% and with a yield of around 53% (Figure 2B). In an attempt to minimize the level of impurities and remove oligomeric protein, a final purification step was performed utilizing a gel filtration 16/60 Superdex™ 200 column, which resulted in the elution of eEF-2K as a major peak around 65-75 mL (Figure 2C). The purified recombinant human eEF-2K was dialyzed against Buffer S1, concentrated, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C. The final protein sample (9 mg) was estimated to be 98% pure, while giving an overall yield of 8% (Table 1). Amino acids analysis confirmed the identity of the purified protein as eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase.

Throughout the entire process of purification, the enzyme appeared as a band around 95 kDa when analyzed by SDS-PAGE, despite its molecular mass being ~ 82 kDa. However, light scattering analysis demonstrated that the purified protein does indeed have a molecular mass around the predicted known size, and hence the gel discrepancy was most likely an artifact of SDS-PAGE.

Characterization of eEF-2K

The goal of this work was to purify bacterially expressed recombinant human eEF-2K that met stringent requirements for kinetic analysis. To assess whether the recombinant kinase resembles the native enzyme purified from mammals, characterization studies with regard to its self-association and activity were carried out. It has been claimed thus far, that in its native state, eEF-2K exists as an elongated monomer of ~ 140 kDa [5, 8, 13, 14]. All other CaM-kinases are known to have a monomeric subunit composition, barring CaMK-II (dodecamer) and phosphorylase kinase (tetramer of tetramers) [43, 44]. Size-exclusion chromatography on a 16/60 Superdex™ 200 gel filtration column indicated that the apparent molar mass of eEF-2K is ~ 160 kDa, consistent with eEF-2K dimerization. However, the elution volumes of proteins in gel filtration are very sensitive to the protein conformation and may not provide accurate molar masses. This may explain the wide range of molar masses reported earlier from gel filtration [5, 8, 13, 14]. Analysis by MALS (Figure 3) shows recombinante EF-2K to have a molar mass of ~ 85 kDa. Experiments were performed on the eluted fractions and the molar mass distribution of eEF-2K as a function of elution volume is presented in Figure 3. This is consistent with the molar mass of ~ 82 kDa determined from the protein sequence. A mass spectrometry analysis of proteolytically cleaved eEF-2K (c.a. 90% coverage) revealed no evidence of significant phosphate incorporation (Tavares et al., in preparation).

Figure 3. Light scattering analysis of unphosphorylated eEF-2K.

The continuous patterns represent the refractive index signal for duplicate runs; horizontal lines represent the calculated molar mass. Analysis indicates that eEF-2K is monomeric with mass of ~85 kDa. The protein concentration at the maximum of the upper curve is ~1.6 μM reflecting a ~30-fold dilution of the injected sample.

To analyze the ability of the purified kinase to phosphorylate its substrate, eEF-2, dose response assays were performed with 2 nM eEF-2K and several concentrations of wheat germ eEF-2 (0-20 μM) as described under ‘Materials and Methods’. Data were fitted using equation 1, where and (Figure 4). The behavior of recombinant human eEF-2K expressed in bacteria resembles that purified from a mammalian source with regards to its ability to phosphorylate eEF-2, with half maximal activity achieved at 5.9 ± 0.4 μM and a catalytic constant of . Earlier reports have suggested that mammalian eEF-2K phosphorylates yeast eEF-2 with a of 2 μM [13]. Additionally, Smailov et al. have shown that eEF-2 from wheat germ is a suitable substrate for eEF-2K purified from an animal source, and is phosphorylated to the same extent as eEF-2 obtained from rabbit reticulocytes [45].

Figure 4. Analysis of the kinase activity of eEF-2K.

Wheat germ eEF-2 dependence assays were performed using 2 nM eEF-2K and 0-20 μM eEF-2 in a suitable buffer as described under ‘Materials and Methods’. The data were fitted to equation 1, where and . Kinase activity was determined by measuring the rate of phosphorylation of eEF-2 (μM.s-1)

CONCLUSION

This study reports for the first time the purification of monomeric tagless recombinant human eEF-2K expressed in bacteria, which mimics the nascent enzyme purified from mammalian sources with respect to its ability to phosphorylate eEF-2.This four-step procedure significantly reduces contaminating bacterial proteins, and yields milligram quantities of kinase per liter of culture. Light scattering analysis confirms the existence of eEF-2K as a monomer, thus deeming it suitable for enzyme kinetic studies, as well as for high throughput screening.

It is known that central signaling pathways like the mTOR and MAPK cascades are able to govern the elongation phase of protein synthesis by modulating the activity of eEF-2K via multisite phosphorylation, thus highlighting the crucial role of the kinase in the regulation of cell viability and growth. The enzyme is also regulated by Ca2+, and it has been shown that Ca2+/CaM-induced autophosphorylation equips the kinase with Ca2+-independence – thus suggesting that it acts as a molecular switch in response to Ca2+ signaling [13, 14]. However, the mechanistic basis for this observation remains unclear. Undoubtedly, the possession of pure tagless recombinant human eEF-2K is a step forward in unraveling the multifaceted mechanism of regulation of this fascinating kinase.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the excellent technical support from Claire Riggs. We are indebted to Dr. Karen Browning (UT Austin) for the provision of wheat germ eEF-2, and Dr. John Tesmer (University of Michigan) and Dr. Neal Waxham (UT Medical School at Houston) for the provision of DNA encoding TEV protease and calmodulin respectively.

This research was supported in part by the grants from the Welch Foundation (F-1390) to K.N. Dalby and the National Institutes of Health to K. N. Dalby (GM59802). A grant from the National Institutes of Health (P01GM078195) supported K. N. Dalby, A. G. Ryazanov and B.E. Turk. Support from Texas Institute for Drug & Diagnostic Development H-F-0032 is also acknowledged by K. N. Dalby. Light-scattering instrumentation is funded by National Science Foundation (Grant MCB-0237651 to A. F. Riggs).

Abbreviations

- BSA

bovine serum albumin fraction V

- CaM

calmodulin

- CaMK

calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylene diaminete traacetic acid

- eEF-2

eukaryotic elongation factor 2

- eEF-2K

eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase

- EGTA

ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid

- EK

enterokinase

- ERK

extracellular-signal-regulated kinases

- (G-D-I)-eEF-2K

recombinant human eEF-2K preceded by three residues (Gly-Asp-Ile) – a remnant of the Trx-His6-tag after cleavage

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- IPTG

isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside

apparent catalytic constant

apparent substrate concentration required to achieve half maximal activity

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MEK

MAPK/ERK kinase

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- Ni-NTA

nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PKA

cAMP-dependent protein kinase

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- TEV

tobacco etch virus

- TPCK

tosyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone

- TRPM7

transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily M, member 7

- Trx-His6-tag

thioredoxin-6xhistidine-tag

apparent maximum velocity

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hershey JWB. Translational Control in Mammalian Cells. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1991;60:717–755. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.003441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morley SJ, Thomas G. Intracellular messengers and the control of protein synthesis. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 1991;50:291–319. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(91)90047-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Proud CG. Protein phosphorylation in translational control. Curr Top Cell Regul. 1992;32:243–369. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-152832-4.50008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhoads RE. Signal Transduction Pathways That Regulate Eukaryotic Protein Synthesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:30337–30340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nairn AC, Bhagat B, Palfrey HC. Identification of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase III and its major Mr 100,000 substrate in mammalian tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:7939–7943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.7939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nairn AC, Palfrey HC. Identification of the major Mr 100,000 substrate for calmodulin-dependent protein kinase III in mammalian cells as elongation factor-2. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1987;262:17299–17303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryazanov AG. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent phosphorylation of elongation factor 2. FEBS Letters. 1987;214:331–334. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryazanov AG, Natapov PG, Shestakova EA, Severin FF, Spirin AS. Phosphorylation of the elongation factor 2: The fifth Ca2+ / calmodulin-dependent system of protein phosphorylation. Biochimie. 1988;70:619–626. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(88)90245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlberg U, Nilsson A, Nygârd O. Functional properties of phosphorylated elongation factor 2. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1990;191:639–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moldave K. Eukaryotic Protein Synthesis. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1985;54:1109–1149. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.005333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moazed D, Noller HF. Intermediate states in the movement of transfer RNA in the ribosome. Nature. 1989;342:142–148. doi: 10.1038/342142a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Proud CG. Peptide-chain elongation in eukaryotes. Mol Biol Rep. 1994;19:161–170. doi: 10.1007/BF00986958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitsui K, Brady M, Palfrey HC, Nairn AC. Purification and characterization of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase III from rabbit reticulocytes and rat pancreas. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:13422–13433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Redpath NT, Proud CG. Purification and phosphorylation of elongation factor-2 kinase from rabbit reticulocytes. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1993;212:511–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller SG, Kennedy MB. Regulation of brain Type II Ca2+ calmodulin-dependent protein kinase by autophosphorylation: A Ca2+-triggered molecular switch. Cell. 1986;44:861–870. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryazanov AG, Ward MD, Mendola CE, Pavur KS, Dorovkov MV, Wiedmann M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Parmer TG, Prostko CR, Germino FJ, Hait WN. Identification of a new class of protein kinases represented by eukaryotic elongation factor-2 kinase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:4884–4889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.4884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryazanov AG, Pavur KS, Dorovkov MV. Alpha-kinases: a new class of protein kinases with a novel catalytic domain. Current Biology. 1999;9:R43–R45. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drennan D, Ryazanov AG. Alpha-kinases: analysis of the family and comparison with conventional protein kinases. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 2004;85:1–32. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6107(03)00060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Middelbeek J, Clark K, Venselaar H, Huynen M, van Leeuwen F. The alpha-kinase family: an exceptional branch on the protein kinase tree. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2010;67:875–890. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0215-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diggle TA, Seehra CK, Hase S, Redpath NT. Analysis of the domain structure of elongation factor-2 kinase by mutagenesis. FEBS Letters. 1999;457:189–192. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pavur KS, Petrov AN, Ryazanov AG. Mapping the Functional Domains of Elongation Factor-2 Kinase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12216–12224. doi: 10.1021/bi0007270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, Li W, Williams M, Terada N, Alessi DR, Proud CG. Regulation of elongation factor 2 kinase by p90RSK1 and p70 S6 kinase. EMBO J. 2001;20:4370–4379. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Redpath NT, Proud CG. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylates rabbit reticulocyte elongation factor-2 kinase and induces calcium-independent activity. Biochem J. 1993;293(Pt 1):31–34. doi: 10.1042/bj2930031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diggle TA, Subkhankulova T, Lilley KS, Shikotra N, Willis AE, Redpath NT. Phosphorylation of elongation factor-2 kinase on serine 499 by cAMP-dependent protein kinase induces Ca2+/calmodulin-independent activity. Biochem J. 2001;353:621–626. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3530621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Browne GJ, Finn SG, Proud CG. Stimulation of the AMP-activated Protein Kinase Leads to Activation of Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 Kinase and to Its Phosphorylation at a Novel Site, Serine 398. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:12220–12231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bagaglio DM, Hait WN. Role of calmodulin-dependent phosphorylation of elongation factor 2 in the proliferation of rat glial cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:1403–1408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parmer TG, Ward MD, Yurkow EJ, Vyas VH, Kearney TJ, Hait WN. Activity and regulation by growth factors of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase III (elongation factor 2-kinase) in human breast cancer*. Br J Cancer. 1998;79:59–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arora S, Yang JM, Kinzy TG, Utsumi R, Okamoto T, Kitayama T, Ortiz PA, Hait WN. Identification and characterization of an inhibitor of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase against human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6894–6899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hait WN, Wu H, Jin S, Yang JM. Elongation factor-2 kinase: its role in protein synthesis and autophagy. Autophagy. 2006;2:294–296. doi: 10.4161/auto.2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu H, Yang J-M, Jin S, Zhang H, Hait WN. Elongation Factor-2 Kinase Regulates Autophagy in Human Glioblastoma Cells. Cancer Research. 2006;66:3015–3023. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu H, Zhu H, Liu DX, Niu T-K, Ren X, Patel R, Hait WN, Yang J-M. Silencing of Elongation Factor-2 Kinase Potentiates the Effect of 2-Deoxy-d-Glucose against Human Glioma Cells through Blunting of Autophagy. Cancer Research. 2009;69:2453–2460. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren H, Tai SK, Khuri F, Chu Z, Mao L. Farnesyltransferase inhibitor SCH66336 induces rapid phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5841–5847. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalby KN, Tekedereli I, Lopez-Berestein G, Ozpolat B. Targeting the prodeath and prosurvival functions of autophagy as novel therapeutic strategies in cancer. Autophagy. 2010;6:322–329. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.3.11625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kapust RB, Tozser J, Fox JD, Anderson DE, Cherry S, Copeland TD, Waugh DS. Tobacco etch virus protease: mechanism of autolysis and rational design of stable mutants with wild-type catalytic proficiency. Protein Eng. 2001;14:993–1000. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.12.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kristelly R, Earnest BT, Krishnamoorthy L, Tesmer JJG. Preliminary structure analysis of the DH/PH domains of leukemia-associated RhoGEF. Acta Crystallographica Section D. 2003;59:1859–1862. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903018067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaertner TR, Kolodziej SJ, Wang D, Kobayashi R, Koomen JM, Stoops JK, Waxham MN. Comparative Analyses of the Three-dimensional Structures and Enzymatic Properties of α, β, γ, and δ Isoforms of Ca2+-Calmodulin-dependent Protein Kinase II. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:12484–12494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forest A, Swulius MT, Tse JKY, Bradshaw JM, Gaertner T, Waxham MN. Role of the N- and C-Lobes of Calmodulin in the Activation of Ca2+/Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase II. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10587–10599. doi: 10.1021/bi8007033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turk BE, Hutti JE, Cantley LC. Determining protein kinase substrate specificity by parallel solution-phase assay of large numbers of peptide substrates. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:375–379. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Callaway KA, Rainey MA, Riggs AF, Abramczyk O, Dalby KN. Properties and Regulation of a Transiently Assembled ERK2·Ets-1 Signaling Complex. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13719–13733. doi: 10.1021/bi0610451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knebel A, Morrice N, Cohen P. A novel method to identify protein kinase substrates: eEF2 kinase is phosphorylated and inhibited by SAPK4/p38δ. EMBO J. 2001;20:4360–4369. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knebel A, Haydon CE, Morrice N, Cohen P. Stress-induced regulation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase by SB 203580-sensitive and -insensitive pathways. Biochem J. 2002;367:525–532. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Browne GJ, Proud CG. A Novel mTOR-Regulated Phosphorylation Site in Elongation Factor 2 Kinase Modulates the Activity of the Kinase and Its Binding to Calmodulin. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:2986–2997. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.7.2986-2997.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soderling TR, Stull JT. Stull, Structure and Regulation of Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinases. Chemical Reviews. 2001;101:2341–2352. doi: 10.1021/cr0002386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swulius M, Waxham M. Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent Protein Kinases. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2008;65:2637–2657. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8086-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smailov SK, Lee AV, Iskakov BK. Study of phosphorylation of translation elongation factor 2 (EF-2) from wheat germ. FEBS Letters. 1993;321:219–223. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]