Introduction

Central serous chorioretinopathy (CSC) is characterized by an idiopathic serous detachment of the neurosensory retina at the macula resulting from deficient pumping and altered barrier function at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). The disease often resolves spontaneously but sometimes recurs or becomes chronic [1, 2].

Chronic CSC occurs more frequently in elderly patients and is often bilateral [3–5]. This disease is characterized by multifocal, irregularly distributed and often widespread RPE changes associated with varying degrees of low-grade leakage. Persistent subretinal fluid in chronic CSC can produce severe and irreversible visual loss [6]. Chronic CSC may be associated with persistent subretinal exudation, extensive RPE atrophy, cystoid macular degeneration, and choroidal neovascularization. These factors lead to a less favorable visual prognosis [7–10].

Use of intravitreal bevacizumab has been reported in the management of CSC [11–13]. Vascular endothelial growth factor has been thought to be involved in fluid leakage in patients with chronic CSC [12]. We studied the effect of intravitreal bevacizumab on in vivo retinal histology by spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT), in bilateral chronic CSC.

Material and methods

The authors confirm adherence to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. A case of bilateral chronic central serous chorioretinopathy was included. After taking a written informed consent, the patient was treated with 1.25 mg/0.05 ml of intravitreal bevacizumab in right eye and 4 weeks later in the left eye. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography [Cirrus high definition OCT (Carl Zeiss Meditec Inc.), CA, USA] was performed before and 6 weeks after the therapy.

Case report

A 53-year male, with coexistent well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus of 8 years duration, presented to our tertiary care center with the complaints of decreased and distorted vision in both the eyes since 1 year. The best-corrected logMAR visual acuity was 1 (20/200) in both the eyes. Slit lamp examination results were unremarkable. Fundus examination of both the eyes revealed RPE atrophy in the posterior pole along with superficial and deep retinal hemorrhages and hard exudates (Fig. 1a and b). Late-phase fluorescein angiography showed multiple window defects due to areas of RPE atrophy. A RPE tract could also be visualized.

Fig. 1.

a Color fundus photograph of the right eye shows retinal pigment epithelium atrophy, few superficial and deep hemorrhages and hard exudates at the posterior pole. b Color fundus photograph of the left eye shows retinal pigment epithelium atrophy tract, few superficial and deep hemorrhages, and hard exudates at the posterior pole

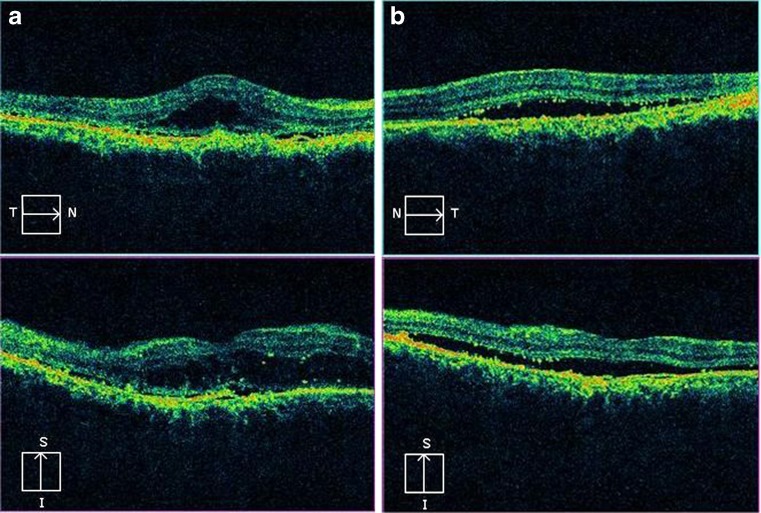

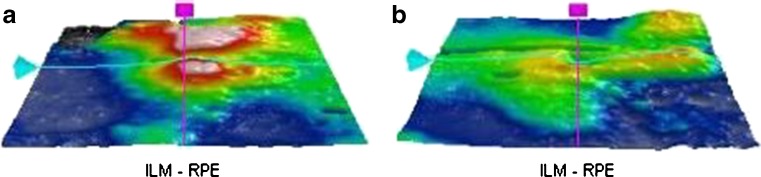

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography of both the eyes showed neurosensory detachment of the macula with retinal pigment epithelial detachment (PED; Fig. 2a and b). Granularity in the outer photoreceptor layer (OPL) and proliferative RPE cells were also observed. The photoreceptor inner segment–outer segment (IS–OS) junction could not be visualized. The RPE layer was found to be hyperplastic in the right eye. The ILM-RPE macular thickness was 444 μm in the right eye and 324 μm in the left eye (Fig. 3a and b). Single-layer RPE map topography showed surface alterations in both eyes.

Fig. 2.

a Spectral domain optical coherence tomography of the right eye shows neurosensory detachment of the macula with retinal pigment epithelial detachment. Granularity in the outer photoreceptor layer and proliferative retinal pigment epithelial cells are also observed. The retinal pigment epithelium is hyperplastic. The photoreceptor IS–OS junction is not visualized. b Spectral domain optical coherence tomography of the left eye shows neurosensory detachment of the macula with retinal pigment epithelial detachment. Granularity in the outer photoreceptor layer and proliferative retinal pigment epithelial cells are also observed. The retinal pigment epithelium is hyperplastic. The photoreceptor IS–OS junction is not visualized

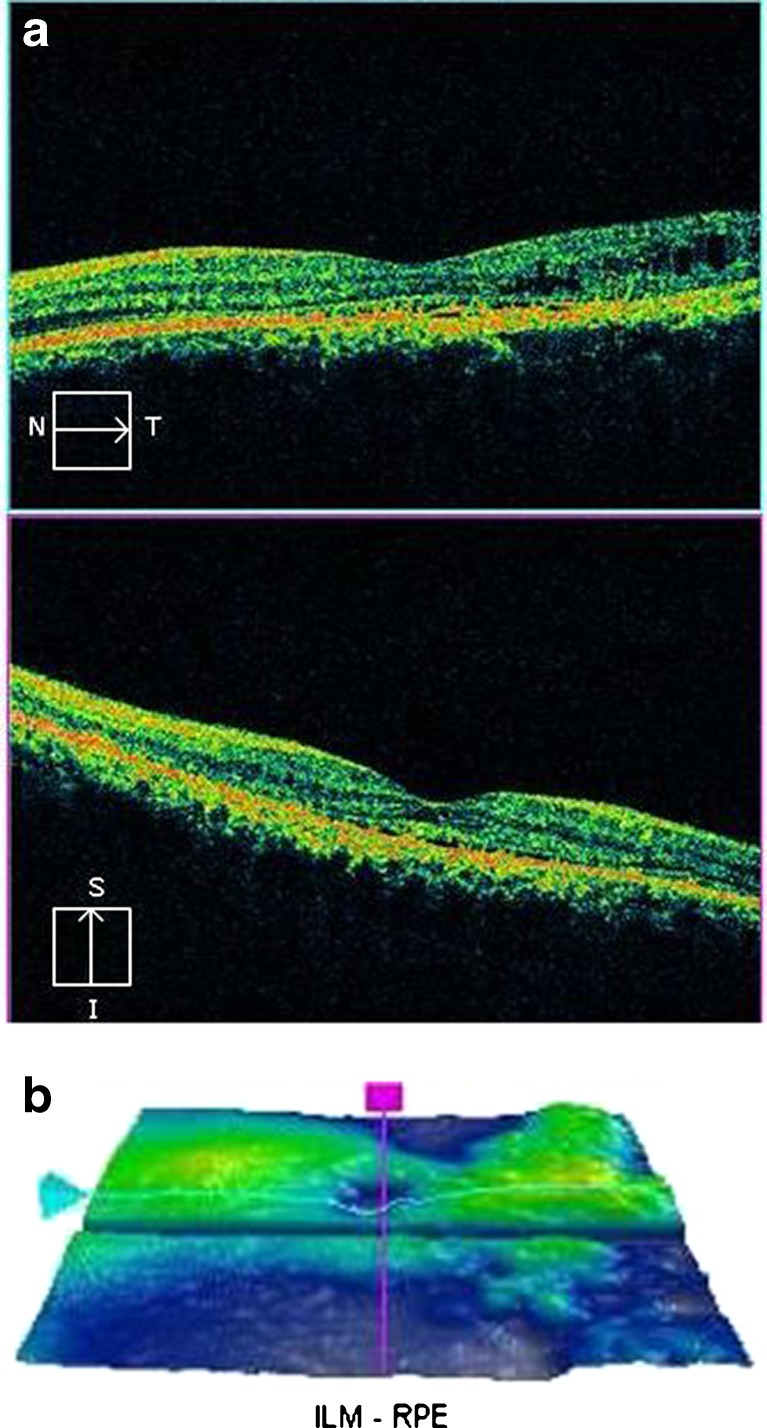

Fig. 3.

a Three-dimensional internal limiting membrane-retinal pigment epithelium map of the right eye shows increased macular thickness. Central sub field thickness is 444 μm. b Three-dimensional internal limiting membrane-retinal pigment epithelium map of the left eye shows increased macular thickness. Central sub field thickness was 324 μm

The patient was treated with 1.25 mg/0.05 ml of intravitreal bevacizumab in the right eye and 4 weeks later in the left eye. Each eye was reassessed 6 weeks after therapy. The best-corrected logMAR visual acuity was 0.78 (20/120) in the right eye and 0.30 (20/40) in the left eye.

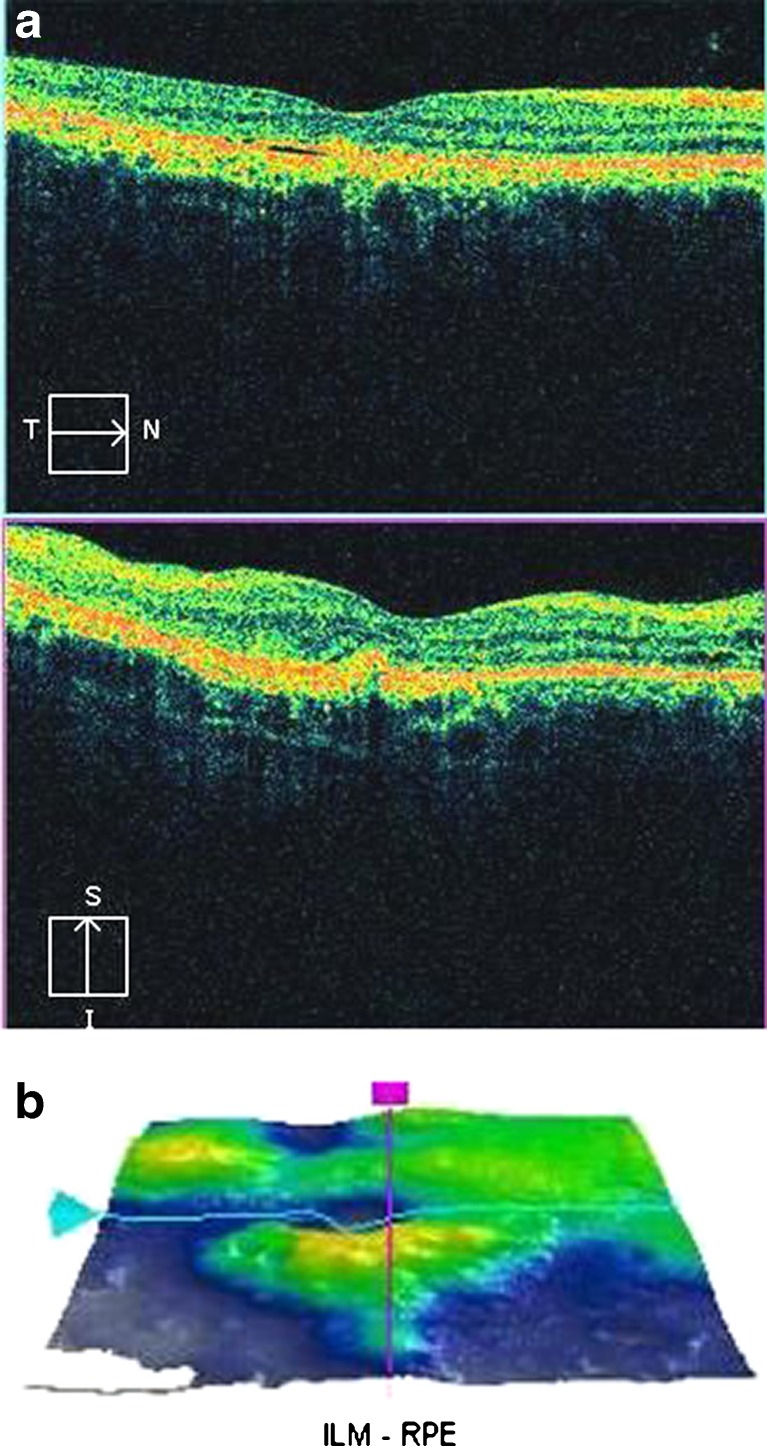

Optical coherence tomography of the right eye showed resolution of subretinal fluid with persistent PED. Foveal contour was restored. Residual granularity at OPL and proliferative RPE cells were visualized. Small cystic spaces were also observed. The photoreceptor IS–OS junction could not be discerned in the subfoveal area. The RPE layer remained hyperplastic (Fig. 4a). The ILM-RPE macular thickness reduced to 216 μm (Fig. 4b). SD-OCT of the left eye showed minimal subretinal fluid in the macula with residual PED. However, granularity over the OPL and proliferative RPE cells could still be observed. The photoreceptor IS–OS junction could be discerned well in the subfoveal area. Multiple cystic spaces were also observed temporally (Fig. 5a). The ILM-RPE macular thickness was 238 μm (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 4.

a Post intravitreal bevacizumab injection, spectral domain optical coherence tomography of the right eye shows resolution of subretinal fluid with persistent pigment epithelial detachment. Foveal contour is restored. Residual granularity at outer photoreceptor layer and proliferative retinal pigment epithelial cells are visualized. Small cystic spaces are also observed. The photoreceptor IS–OS junction is not visible in the subfoveal area. The retinal pigment epithelium layer remains hyperplastic. b Three-dimensional internal limiting membrane-retinal pigment epithelium map of the right eye shows decreased macular thickness. Central subfield thickness is 216 μm

Fig. 5.

a Post intravitreal bevacizumab injection, spectral domain optical coherence tomography of the left eye shows resolution of subretinal fluid. Foveal contour is restored. Residual granularity at outer photoreceptor layer and proliferative retinal pigment epithelial cells are visualized. The photoreceptor IS–OS junction is visualized in the subfoveal area. b Three-dimensional internal limiting membrane-retinal pigment epithelium map of the left eye shows decreased macular thickness. Central subfield thickness is 238 μm

At 1-year follow up, visual acuity was maintained in both the eyes.

Discussion

Intravitreal bevacizumab has been shown to be effective in the treatment of chronic and recurrent CSC in terms of both anatomical and functional recovery [12]. In a 1-year follow up examination, intravitreal injection of bevacizumab was well tolerated in maintaining vision and reducing serous retinal detachment in patients with chronic CSC [13].

Our case showed that although there was significant improvement in “in vivo” histology as seen on SD-OCT, the functional recovery in terms of best-corrected visual acuity was minimal in the right eye. This might be attributed to the non restoration of the IS–OS junction and to the hyperplastic nature of the RPE. Better visual recovery in the left eye is attributable to the restoration of IS–OS junction. Residual granularity in the OPL and proliferative RPE cells in both eyes are additional factors responsible for incomplete visual recovery.

The RPE produces molecules that support the survival of photoreceptors and ensure a structural basis for the optimal circulation and supply of nutrients. The cyclical process of photolysis and regeneration of light-sensitive pigments in the disk membranes of the photoreceptor outer segments depends on an exchange of retinoids between the photoreceptors and the RPE [14]. The RPE also maintains photoreceptor excitability by phagocytosing the shed photoreceptor outer segment and by releasing molecules such as docosahexaenoic acid and retinal that rebuild light-sensitive outer segments from the base of the photoreceptors [15]. This maintains a constant length of the photoreceptor outer segments. Intravitreal bevacizumab therapy did not have influence on the RPE and the proliferative RPE cells. This led to suboptimal visual recovery.

During macular detachment, a preserved OPL is significantly associated with a higher visual acuity compared with an atrophic OPL. When the foveal OPL appears abnormal, because of thickening and granulation on the SD-OCT sections, only partial recovery of visual acuity seems to occur with macular reattachment [16]. The photoreceptors are expected to die when detachment separates them from the retinal pigment epithelium and the choriocapillaris, their source of oxygen and nutrients. There is a great deal of histopathologic evidence of photoreceptor death when this occurs [17–20]. The granulated OPL seen on SD-OCT could either be outer segment disks dismantlement and disk material or protein precipitates, in accordance with the classic interpretation of the yellowish subretinal specks visible during fundus examination [16] or macrophages with the phagocytized photoreceptor outer segments [21]. It has a greater impact on cones than rods [22]. The presence of this granularity in both the eyes even after treatment with bevacizumab might be responsible for the poorer functional recovery.

Bevacizumab injections do not significantly influence BCVA, notwithstanding a substantial improvement in SD-OCT appearance. Prolonged presence of subretinal fluid in chronic CSC leads to photoreceptor damage. Macular damage already occurs by the time intravitreal bevacizumab therapy is used in chronic CSC.

Contributor Information

Sandeep Saxena, Phone: +91-941-5160528, Email: sandeepsaxena2020@yahoo.com.

Astha Jain, Phone: +91-885-8654658, Email: astha2jain@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Gass JDM. Pathogenesis of disciform detachment of the neuro-epithelium. II. Idiopathic central serous choroidopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1960;63:587–615. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert CM, Owens SL, Smith PD, Fine SL. Long-term follow-up of central serous chorioretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68:815–820. doi: 10.1136/bjo.68.11.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yannuzzi LA, Shakin JL, Fisher YL, Altomonte MA. Peripheral retinal detachments and retinal pigment epithelial atrophic tracts secondary to central serous pigment epitheliopathy. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1554–1572. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iida T, Hagimura N, Sato T, Kishi S. Evaluation of central serous chorioretinopathy with optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:16–20. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)00272-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomolin JE. Choroidal neovascularization and central serous chorioretinopathy. Can J Ophthalmol. 1989;24:20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang WC, Chen WL, Tsai YY, Chiang CC, Lin JM. Intravitreal bevacizumab for treatment of chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Eye. 2009;23:488–489. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ie D, Yannuzzi LA, Spaide RF, Rabb MF, et al. Subretinal exudative deposits in central serous chorioretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:349–353. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.6.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iida T, Spaide RF, Haas A, et al. Leopard-spot pattern of yellowish subretinal deposits in central serous chorioretinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;20:37–42. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iida T, Yannuzzi LA, Spaide RF, et al. Cystoid macular degeneration in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 2003;23:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200302000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang M, Munch IC, Hasler PW, Prünte C, Larsen M. Central serous chorioretinopathy. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2008;86:126–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee ST, Adelan RA. The treatment of recurrent central serous chorioretinopathy with intravitreal bevacizumab. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2011;27:611–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Schaal KB, Hoeh AE, Scheuerle A, Schuett F, Dithmar S. Intravitreal bevacizumab for treatment of chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009;19:613–617. doi: 10.1177/112067210901900415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue M, Kadonosono K, Watanabe Y, et al. Results of one-year follow-up examinations after intravitreal bevacizumab administration for chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmologica. 2011;225:37–40. doi: 10.1159/000314709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simo R, Villarroel M, Corraliza L, Hernandez C, Garcia-Ramirez M. The retinal pigment epithelium: something more than a constituent of the blood-retinal barrier-implications for the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010. doi:10.1155/2010/190724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Bibb C, Young RW. Renewal of fatty acids in the membranes of visual cell outer segments. J Cell Biol. 1974;61:327–343. doi: 10.1083/jcb.61.2.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piccolino FC, Llongrais RR, Ravera G, et al. The foveal photoreceptor layer and visual acuity loss in central serous chorioretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroll AJ, Machemer R. Experimental retinal detachment in the owl monkey. III. Electron microscopy of retina and pigment epithelium. Am J Ophthalmol. 1968;66:410–427. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(68)91524-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson DH, Guerin CJ, Erickson PA, Stern WH, Fisher SK. Morphological recovery in the reattached retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986;27:168–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook B, Lewis GP, Fisher SK, Adler R. Apoptotic photoreceptor degeneration in experimental retinal detachment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:990–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hisatomi T, Sakamoto T, Goto Y, et al. Critical role of photoreceptor apoptosis in functional damage after retinal detachment. Curr Eye Res. 2002;24:161–172. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.24.3.161.8305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kon Y, Iida T, Maruko I, Saito M. The optical coherence tomography-ophthalmoscope for examination of central serous chorioretinopathy with precipitates. Retina. 2008;28:864–869. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181669795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakai T, Calderone JB, Lewis GP, et al. Cone photoreceptor recovery after experimental detachment and reattachment: an immunocytochemical, morphological, and electrophysiological study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:416–425. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]