Abstract

Interleukin-17 (IL-17) producing Type17 T-cells, specifically T-helper (Th)17 cells reactive to central nervous system (CNS) autoantigens, manifest a higher migratory capability to the CNS parenchyma compared with other T-cell subpopulations due to their ability to penetrate the blood brain barrier (BBB). In the field of cancer immunotherapy, there are now a number of cell therapy approaches including early studies using T-cells transduced with chimeric antigen receptors in hematologic malignancy, suggesting that the use of T-cells or genetically modified T-cells could have a significant role in effective cancer therapy. However, the successful application of this strategy in solid tumors, such as CNS tumors, requires careful consideration of critical factors to improve the tumor-homing of T-cells. The current review is dedicated to discuss recent findings on the role of Type17 T-cells in CNS autoimmunity and cancer. The insight gained from these findings may lead to the development of novel therapeutic and prophylactic strategies for CNS autoimmunity and tumors.

Keywords: Th17, IL-17, autoimmunity, central nervous system, multiple sclerosis, gliomas, adoptive transfer therapy

Introduction

Recent studies of autoimmune conditions in the central nervous system (CNS) have revealed that interleukin-17 (IL-17) producing Type17 T-cells, specifically T-helper (Th)17 cells reactive to CNS autoantigens, manifest a higher migratory capability to the CNS parenchyma compared with other T-cell subpopulations due to their ability to penetrate the blood brain barrier (BBB). In the field of cancer immunotherapy, there are now a number of cell therapy approaches1 including early studies using T-cells transduced with chimeric antigen receptors in hematologic malignancy2,3, suggesting that the use of T-cells or genetically modified T-cells could have a significant role in effective cancer therapy. However, the successful application of this strategy in solid tumors requires careful consideration of critical factors to improve the tumor-homing of T-cells. Especially, immunotherapy for CNS tumors, such as malignant glioma, can be hindered by suboptimal infiltration by immune effector cells and tumor elaboration of immunosuppressive cytokines. Although the induction of CNS autoimmunity should be avoided, recent studies suggest that clinical benefits from cancer immunotherapy may be associated with autoimmunity4,5. The current review is dedicated to discuss recent findings on the role of Type17 T-cells in CNS autoimmunity and cancer. The insight gained from these findings may lead to the development of novel therapeutic and prophylactic strategies for CNS autoimmunity and tumors.

Th17 cells efficiently migrate to the brain in autoimmune conditions

Recent discoveries in the field of central nervous system (CNS) autoimmunity research provide us with valuable insight as to critical immunoregulatory mechanisms operated by a relatively novel class of helper T-cells, T helper (Th)17 cells in the CNS. Interleukin-17 (IL-17; originally termed CTLA8, also known as IL-17A) belongs to a family of six members (IL-17A, IL-17B, IL-17C, IL-17D, IL-17E and IL-17F) and has been of great interest recently owing to the discovery that the production of IL-17 characterizes Th17 cells. The development of Th17 cells is distinct from the development of Th1, Th2 and regulatory T (Treg) cells and is characterized by predominant production of IL-17 as well as their developmental control by retinoic acid-related orphan receptor (ROR)γt and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)6. Th17 cells produce IL-17, IL-6, IL-21, IL-22, IL-23 and TNF-α.

Multiple sclerosis (MS), and its experimental model, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) are CNS autoimmune conditions characterized by demyelination and axonal lesion mediated by CD4+ T cells with a proinflammatory Th1 and Th17 phenotype, macrophages, and soluble inflammatory mediators [reviewed7,8]. EAE was initially induced by immunization with myelin proteins emulsified in Complete Freund's Adjuvant, but can also be induced by adoptive transfer of myelin-specific CD4+ Th1 cells into naïve recipient mice9,10. However, IFN-γ and IFN-γR-deficient mice are susceptible to EAE11. Discovery of Th17 cells led to the to speculation that myelin-specific Th17 cells were the primary encephalitogenic T cell population in EAE, and perhaps MS. Generation of IL-17 deficient mice showed that EAE is less severe in the absence of IL-1712, but is not necessary for the development of EAE13. Another cytokine IL-23, was found to promote the expansion of myelin-specific IL-17+ T-cells derived from mice immunized with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), and these IL-23-driven IL-17+ T cells were capable of transferring EAE14. The critical role of IL-23 in the development of CNS inflammation was originally thought to be due to its role in enhancing IL-17 production, but more recently it has been found that IL-23 plays a critical role in homing to the CNS and survival of myelin-specific T cells in the CNS microenvironment15. Investigation into EAE8 models demonstrated that the pathology induced by Th1 and Th17 cells is distinct16,17. Classical EAE induced by Th1 cells is characterized by an ascending paralysis, while EAE induced by Th17 cells is often characterized by spinning, ataxia, spasticity and proprioceptive defects17. Interestingly, administration of IL-17 neutralizing antibody to EAE-affected mice results in a decrease in atypical EAE, such as ataxia, and an increase in classical EAE, such as paralysis17.

The blood brain barrier (BBB) disruption is an early and central event in MS pathogenesis. Autoreactive Th17 cells can migrate through the BBB by the production of cytokines such as IL-17 and IL-22, which disrupt tight junction proteins in the CNS endothelial cells18. Moreover, Th17 cells express high levels of molecules such as CCR6, which has a crucial role in Th17 infiltration into the CNS15,19. Furthermore, Th17 cells produce CCL20 (the ligand of CCR6) in high levels, suggesting a possible positive feedback cycle20–22. The upregulated expression of both CCR6 and CCL20 was reported in EAE 22. Th17 cells expressing CCR6 infiltrate into the CNS by interacting with CCL20, which leads to inflammation and increasing BBB permeability and enhancing subsequent infiltration of other lymphocytes, such as CCR6+ dendritic cells8,15. Indeed, in MS patients, the production of IL-17 correlates with the number of active plaques on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which are caused by BBB breakdown23. Moreover, IL-17 generation in CNS infiltrating T cells and glial cells is associated with active disease in MS24 and the frequency of Th17 cells in the CSF of MS patients is significantly increased at the time of clinical exacerbations compared with clinical remission phases of the disease25. However, it was reported that T-bet positive Th17 cells are encephalitogenic, while T-bet negative Th17 cells are not encephalitogenic26. Thus, Th17 cells differ in their pathogenic potential because of a transcription factor previously known for its role in Th1 cells26.

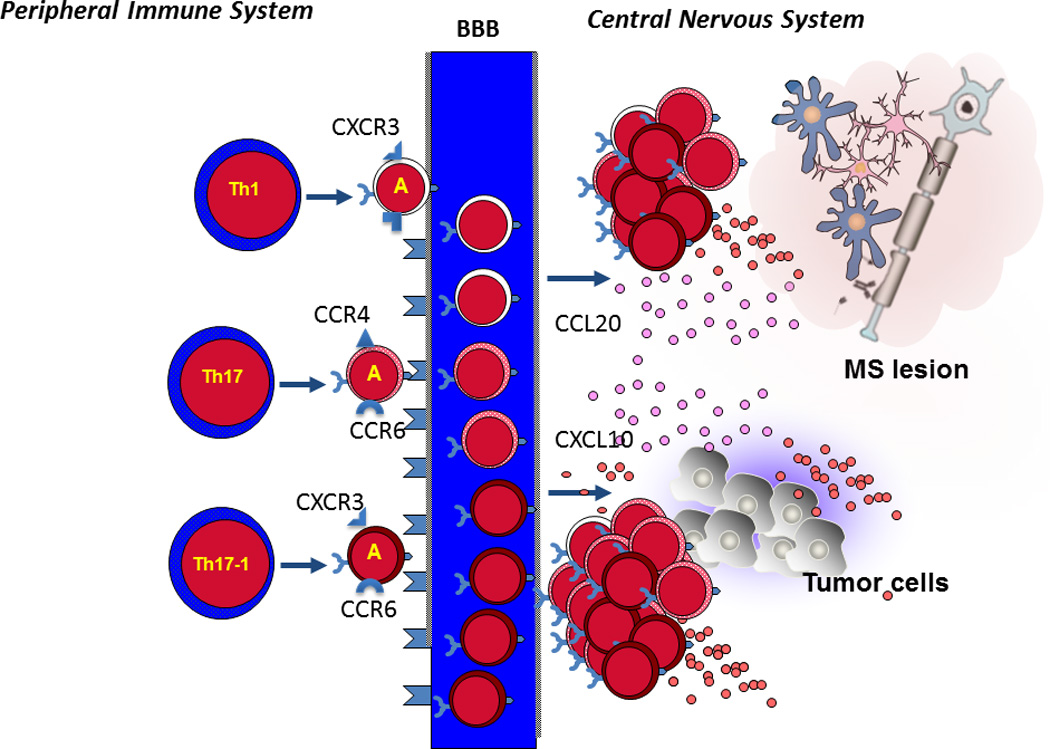

In addition to CD4+IL-17+ Th17 cells, a new putative subtype of IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells with CD4+IL-17+IFNγ+ (Th17-1 cells) double-positive phenotype has also been identified, and the presence of these cells has been described in MS and EAE27,28. The Th17-1 cells isolated from the CSF of MS patients express high levels of CD2825 and are closer to Th17 than to Th1 cells phenotypically25. Th17-1 cells infiltrate the brain prior to the development of clinical symptoms of EAE and this coincides with activation of CD11b+ microglia and local production of IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6 in the CNS. Furthermore, Th17-1 cells are potent activators of pro-inflammatory cytokines whereas Th1 cells are less effective29. Interestingly, the pattern of chemokine receptor expression in Th17-1 cells can discriminate them from Th17 cells. Th17 cells express CCR6 and CCR4, whereas Th17-1 cells express CCR6 and CXCR330 (Figure 1). The Th17-1 cells in MS patients appear to cross the BBB more efficiently18. Interestingly, both Th17 and Th17-1 cells appear to be resistant to Treg mediated suppression25.

Figure 1.

Naïve CD4+ T cells are activated and differentiated in the periphery, then the activated T cells (marked by A) can cross the blood brain barrier (BBB) and accumulate in the central nervous system. Th1 cells express CXCR3, Th17 cells express CCR6 and CCR4, and Th17-1 cells express CCR6 and CXCR3. The chemokines CCL20 and CXCL10 expressed by inflammatory lesions in MS or tumor cells in the CNS enhance recruitment of activated Th1, Th17 and Th17-1 across the blood brain barrier with a selective advantage for Th17-1 cells that express CCR6 and CXCR3.

Type17 T-cells in cancer

The role of Type17 T-cells and Type17-associated cytokines in cancer has been highly controversial, and both pro- and anti-tumor functions have been reported. There are excellent reviews on this topic [reviewed in31–33]. This controversy arises at least partially because most discussions on this issue did not clearly separate the evaluation of Type17 T-cells versus a variety of similar but not identical biological conditions/factors, such as IL-17+ cells from other immune populations, genetic deletion of IL-17 from the entire system (i.e. IL-17-knockout mice), and IL-23, a cytokine that promotes the survival and expansion of Type17 T-cells31–33. Furthermore, conflicting results have been seen in human versus mouse studies and with the use of immunocompetent versus immunodeficient mice. Nonetheless, the key feature of human tumor-associated Type17 T-cells identified thus far is their polyfunctional cytokine profile33,34. This supports the notion of Type17 T-cell plasticity in vivo, and a fraction of Type17 T-cells may be shifted to Type1-type cells in the inflammatory environments35–39. This could partially explain why the infiltration of functional Type17 T-cells in the tumor correlates with reduced tumor progression and improved patient survival in human epithelial cancer34,40,41.

The in vivo plasticity of Type17 T-cells may be the key aspect we need to understand for development of cancer immunotherapy strategies using Th17 and/or Tc17 cells. Therefore, in this review, we will focus on discussing the results of Type17 T-cell adoptive transfer. Unlike the results with IL-17-deficient mice showing both pro- and anti-cancer roles of IL-17, adoptive transfer experiments unanimously demonstrated anti-tumor efficacy at various degrees and different mechanisms, involving conversion from Type17 to Type1 (IFN-γ-producing) T-cells. The following table summarizes the published reports in this regard.

Table 1.

| Tumor Model | T-cell populations | Effects and Major Observations | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subcutaneous (s.c.) B16 melanoma | TRP-1-specific Th17 | Th17 more effective than Th1 in an IFN-γ-dependent manner (less dependent upon IL17 and IL-23) | 42 |

| s.c. B16 melanoma | GP100-specific Type17 CD8+ T-cells | converted in vivo to IFN-γ-producing effector cells and demonstrated greater anti-tumor effects and persistence compared with non-polarized T-cells | 43 |

| A variety of mouse tumors s.c. and lung | TRP-1 or OVA-specific Th17 | Activation of CD8+ CTLs and CCL20-mediated recruitment of dendritic cells | 44 |

| NOD/scid/IL-2Rγnull bearing s.c. human mesothelioma M108 | ICOS-stimulated IL-17+IFN-γ+ human T cells | Chimeric Antigen Receptor-transduced T-cells demonstrated enhanced anti-tumor activity and engraftment in vivo | 45 |

| s.c. and lung metastasis model of B16-OVA | OVA-specific IL-17+ CD8+ T-cells (Tc17) | Approximately 10–50 times as many Tc17 effectors are required compared with Tc1 effectors to exert the same level of control over tumor growth. | 46 |

| s.c. B16 melanoma | TRP-1-specific Th17 | Th17 cells are long lived, and maintain a core molecular signature resembling early memory CD8+ cells with stem cell-like properties | 47 |

In mice with established tumors, both Th1742,44 and Tc1746 (including cells described as Type17 CD8+ T-cells with anti-tumor activities in vivo43) populations have exhibited potent antitumor efficacy when administered as adoptive cell therapy. In mice pretreated with whole-body radiation for lymphodepletion, infused cells started to produce IFN-γ as well (i.e., Type17-1 T-cells), and induced tumor regression in an IFN-γ dependent manner, and persisted in the host longer than non-polarized cells42,43. On the other hand, in non-lymphopenic hosts44, the therapeutic effects of Th17 can be independent of IFN-γ. In this referenced study44, adoptively transferred Th17 cells elicited a remarkable activation of anti-tumor CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs) via recruitment of dendritic cells (DCs) into the tumor tissues and in draining lymph nodes. These effects were mediated by Th17-induced CCL20 production by tumor tissues and attraction of CCR6+ DCs.

These observations on long persistence of Th17 cells in vivo may have been counter-intuitive because they typically display low expression of CD27 and other phenotypic markers of terminal differentiation. Muranski et al. reported that murine Th17 cells actually maintain a core molecular signature resembling early memory CD8+ cells with stem cell-like properties, such as high expression of Tcf7 and accumulated β-catenin. In vivo, Th17 cells gave rise to Th1-like effector cell progeny and also self-renewed and persisted as IL-17A-secreting cells. Multipotency was required for Th17 cell-mediated tumor eradication because effector cells deficient in IFN-γ or IL-17A had impaired activity. Thus, Th17 cells are not always short lived and are a less-differentiated subset capable of superior persistence and functionality47.

The interesting conversion of Type17 T-cells into Type1 T-cells in cancer-bearing hosts is not merely a phenomenon in rodents, but relevant to humans. A lung cancer patient mounted a spontaneous and concurrent Th17 and Th1 responses to a tumor antigen MAGE-A348. MAGE-A3-specific IL-17+ T cells were mainly CCR7+ central memory T cells, whereas IFN-γ+ cells were enriched for CCR7− effector memory T cells. Furthermore, the antigen specific Th17-1 (IL-17+/IFN-γ+) cells contained the CCR6+CCR4+ and CCR6+CXCR3+ fractions at early and late differentiation stages, respectively, whereas the CCR6−CXCR3+ fraction contained a distinct Th1 population. These findings suggest a differentiation model in which tumor antigen-specific CD4+ T cells that are primed under Th17 polarizing conditions can progressively convert into IFN-γ-secreting cells in vivo as they differentiate into effector T cells.

With regard to practical methods to generation of human Type17 T-cells for adoptive T-cell therapy, although ex vivo induction of Type17 T-cells has been established [reviewed6–8], Paulos et al. recently published a novel method for the expansion of human Th17 cells suitable for adoptive T-cell therapy45. When peripheral blood CD4+ T-cells are sorted into various subsets based on their expression of chemokine receptors and other cell surface molecules, approximately 40% of CCR4+CCR6+ cells constitutively express inducible co-stimulator (ICOS), whereas the Th1 and Th2 subsets do not express ICOS. In vitro stimulation of the CCR4+CCR6+ cells with ICOS ligand (ICOSL) followed by polarization with IL-6, TGF-β, IL-1β, IL-23, and neutralizing IL-4 Abs promotes the robust expansion of IL-17+IFN-γ+ human T cells (i.e. Th17-1 cells), and the antitumor activity of these cells after adoptive transfer into mice bearing large human tumors is superior to that of CD28-induced Th1 cells45. The therapeutic effectiveness of ICOS-expanded cells is associated with enhanced functionality and engraftment in vivo. These findings provide not only strong rationale to employ Th17 cells but also a practical method to expand these cells for near future therapy.

Th17 and brain tumors

Significant roles of Th17 cells in CNS autoimmunity as well as cancer immunology prompted some investigations on Type17 responses in CNS tumors. Wainwright et al. demonstrated presence of IL-17A mRNA expression as well as Th17 cells in both human and mouse GL261 gliomas49. Among glioma-infiltrating Th17 cells, 5–10% of them co-expressed the Th1 and Th2 lineage markers, IFN-γ and IL-4, respectively, and 20–25% co-expressed the Treg lineage marker FoxP3. This is interesting because as discussed in the previous section42–44, Th17 cells infiltrating cancers of other organs often convert to Th1 (IFN-γ producing) cells. These data suggest a possibility of unique immunological environment associated with brain tumors. In the relevant topic, Cantini et al.50 investigated Th17 cells in the GL261-glioma model. Contrary to the aforementioned study49, GL261-infiltrating Th17 cells did not express Foxp3. To determine the direct effects of glioma-bearing host conditions on Th17 functions, they isolated splenic Th17 cells derived from non-glioma-bearing (nTh17) or glioma-bearing mice (gTh17). When those cells were adoptively transferred directly into the intracranial GL261 gliomas, nTh17 cells conferred significantly longer survival than gTh17 cells. Interestingly, injection of nTh17, but not gTh17, induced IFN-γ and TNF-α in the tumor environment, suggesting that Th17 cells may undergo systemic suppression by glioma-derived factors.

In regard to the IL-17 mRNA expression in primary glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), Schwartzbaum et al. evaluated mRNA expression of inflammation-related genes in 142 GBM tissue samples, especially in correlation with expression of CD133 as a GBM stem cell marker51. While 69% of 919 allergy- and inflammation-related genes are negatively correlated with CD133 expression, IL-17-β and 2 IL-17 receptors demonstrated trends towards positive correlations. In a study by Hu et al., higher mRNA expression levels of Th17-relevant cytokines were observed in glioma tissues when compared to trauma tissues, although analyses of peripheral blood mononuclear cells demonstrated no significant differences in the number of Th17 cells between glioma patients and healthy donors52. Mechanistic laboratory studies are warranted to determine the biological significance of these observations.

In terms of studies on Th17 cells in non-glial brain tumors, Zhou et al. demonstrated presence of Th17 cells in medulloblastoma-infiltrating T-cells53. Compared with 17 healthy volunteers, 23 patients with medulloblastoma had a higher proportion of Th17 cells in their peripheral blood. Furthermore, the mRNA levels for Th17-related factors (IL-17, IL-23 and ROR) in tumor tissues and the serum concentrations of IL-17 and IL-23 protein were significantly increased in patients with medulloblastoma. The results suggest that Th17 cells may contribute to medulloblastoma pathogenesis.

Concluding Remarks

In this review article, we discussed recent findings on the role of Type17 T-cells in CNS autoimmunity and tumors. Th17 as well as Th1 cells can be encephalitogenic and both of these effector T cell populations can cause CNS inflammation and demyelinating lesions. However, cytokine production is not sufficient for encephalitogenicity. Expression of chemokine receptors, activation markers and transcription factors are critical determinants of pathogenicity. These various transcription factors and cytokines may contribute to a final common pathway, or synergize to induce encephalitogenicity but the exact mechanisms are still under investigation. Although publications on the role of IL-17 and IL-17-associated cytokines in cancer to date report both pro- and anti-tumor functions, it appears consistent that adoptively transferred Type17 T-cells may mediate potent anti-tumor immunity due to their longevity as well as ability to develop into Type1 cells in cancer-bearing hosts. Adoptively transferred Type17 T-cells also impact the immunological microenvironment of the tumor and induce other effector functions that contribute to the anti-tumor responses. In primary CNS tumors, spontaneous Type17 T-cell responses seem to exist, but investigations on their role have just started. Spurred by intriguing observations from CNS autoimmunity research, further evaluations on the therapeutic applications of Typ17 T-cells for CNS tumors are clearly warranted.

Acknowledgment

Grant Support: 2R01NS055140, 2P01 NS40923, 2P01 NS40923 and Musella Foundation for Brain Tumor Research and Information to HO. R01AI067472, AI058680 and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society RG3666 to S.J.K.

Reference List

- 1.Rosenberg SA. Cell transfer immunotherapy for metastatic solid cancer[mdash]what clinicians need to know. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:577–585. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalos M, Levine BL, Porter DL, et al. T Cells with Chimeric Antigen Receptors Have Potent Antitumor Effects and Can Establish Memory in Patients with Advanced Leukemia. Science Translational Medicine. 2011;3:95ra73. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porter DL, Levine BL, Kalos M, et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor–Modified T Cells in Chronic Lymphoid Leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koon H, Atkins M. Autoimmunity and immunotherapy for cancer. N.Engl.J.Med. 2006;354:758–760. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gogas H, Ioannovich J, Dafni U, et al. Prognostic significance of autoimmunity during treatment of melanoma with interferon. N.Engl.J.Med. 2006;354:709–718. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters A, Lee Y, Kuchroo VK. The many faces of Th17 cells. Current Opinion in Immunology. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jadidi-Niaragh F, Mirshafiey A. Th17 Cell, the New Player of Neuroinflammatory Process in Multiple Sclerosis. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 2011;74:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2011.02536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-behi M, Rostami A, Ciric B. Current Views on the Roles of Th1 and Th17 Cells in Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 2010;5:189–197. doi: 10.1007/s11481-009-9188-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ando DG, Clayton J, Kono D, et al. Encephalitogenic T cells in the B10.PL model of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE) are of the Th-1 lymphokine subtype. Cellular immunology. 1989;124:132–143. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(89)90117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pettinelli CB, McFarlin DE. Adoptive transfer of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in SJL/J mice after in vitro activation of lymph node cells by myelin basic protein: requirement for Lyt 1+ 2- T lymphocytes. Journal of immunology. 1981;127:1420–1423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willenborg DO, Fordham S, Bernard CC, et al. IFN-gamma plays a critical down-regulatory role in the induction and effector phase of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-induced autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of immunology. 1996;157:3223–3227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Komiyama Y, Nakae S, Matsuki T, et al. IL-17 plays an important role in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of immunology. 2006;177:566–573. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haak S, Croxford AL, Kreymborg K, et al. IL-17A and IL-17F do not contribute vitally to autoimmune neuro-inflammation in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2009;119:61–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI35997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein WM, et al. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;201:233–240. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reboldi A, Coisne C, Baumjohann D, et al. C-C chemokine receptor 6-regulated entry of TH-17 cells into the CNS through the choroid plexus is required for the initiation of EAE. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:514–523. doi: 10.1038/ni.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroenke MA, Carlson TJ, Andjelkovic AV, et al. IL-12– and IL-23–modulated T cells induce distinct types of EAE based on histology, CNS chemokine profile, and response to cytokine inhibition. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2008;205:1535–1541. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stromnes IM, Cerretti LM, Liggitt D, et al. Differential regulation of central nervous system autoimmunity by TH1 and TH17 cells. Nat Med. 2008;14:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nm1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kebir H, Kreymborg K, Ifergan I, et al. Human TH17 lymphocytes promote blood-brain barrier disruption and central nervous system inflammation. Nat Med. 2007;13:1173–1175. doi: 10.1038/nm1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamazaki T, Yang XO, Chung Y, et al. CCR6 Regulates the Migration of Inflammatory and Regulatory T Cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2008;181:8391–8401. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirota K, Yoshitomi H, Hashimoto M, et al. Preferential recruitment of CCR6-expressing Th17 cells to inflamed joints via CCL20 in rheumatoid arthritis and its animal model. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2007;204:2803–2812. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohler RE, Caon AC, Willenborg DO, et al. A Role for Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-3α/CC Chemokine Ligand 20 in Immune Priming During T Cell-Mediated Inflammation of the Central Nervous System. The Journal of Immunology. 2003;170:6298–6306. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liston A, Kohler RE, Townley S, et al. Inhibition of CCR6 Function Reduces the Severity of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis via Effects on the Priming Phase of the Immune Response. The Journal of Immunology. 2009;182:3121–3130. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0713169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hedegaard CJ, Krakauer M, Bendtzen K, et al. T helper cell type 1 (Th1), Th2 and Th17 responses to myelin basic protein and disease activity in multiple sclerosis. Immunology. 2008;125:161–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tzartos JS, Friese MA, Craner MJ, et al. Interleukin-17 Production in Central Nervous System-Infiltrating T Cells and Glial Cells Is Associated with Active Disease in Multiple Sclerosis. The American Journal of Pathology. 2008;172:146–155. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brucklacher-Waldert V, Stuerner K, Kolster M, et al. Phenotypical and functional characterization of T helper 17 cells in multiple sclerosis. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2009;132:3329–3341. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Y, Weiner J, Liu Y, et al. T-bet is essential for encephalitogenicity of both Th1 and Th17 cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2009;206:1549–1564. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abromson-Leeman S, Bronson RT, Dorf ME. Encephalitogenic T cells that stably express both T-bet and RORγt consistently produce IFNγ but have a spectrum of IL-17 profiles. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2009;215:10–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suryani S, Sutton I. An interferon-γ-producing Th1 subset is the major source of IL-17 in experimental autoimmune encephalitis. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2007;183:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy ÁC, Lalor SJ, Lynch MA, et al. Infiltration of Th1 and Th17 cells and activation of microglia in the CNS during the course of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2010;24:641–651. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Rivino L, Geginat J, et al. Surface phenotype and antigenic specificity of human interleukin 17-producing T helper memory cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:639–646. doi: 10.1038/ni1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maniati E, Soper R, Hagemann T. Up for Mischief[quest] IL-17/Th17 in the tumour microenvironment. Oncogene. 2010;29:5653–5662. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilke CM, Kryczek I, Wei S, et al. Th17 cells in cancer: help or hindrance? Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:643–649. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou W, Restifo NP. TH17 cells in tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:248–256. doi: 10.1038/nri2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kryczek I, Banerjee M, Cheng P, et al. Phenotype, distribution, generation, and functional and clinical relevance of Th17 cells in the human tumor environments. Blood. 2009;114:1141–1149. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-208249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy KM, Stockinger B. Effector T cell plasticity: flexibility in the face of changing circumstances. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:674–680. doi: 10.1038/ni.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Annunziato F, Romagnani S. The transient nature of the Th17 phenotype. European Journal of Immunology. 2010;40:3312–3316. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin-Orozco N, Chung Y, Chang SH, et al. Th17 cells promote pancreatic inflammation but only induce diabetes efficiently in lymphopenic hosts after conversion into Th1 cells. European Journal of Immunology. 2009;39:216–224. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bending D, De La Peña H, Veldhoen M, et al. Highly purified Th17 cells from BDC2.5NOD mice convert into Th1-like cells in NOD/SCID recipient mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2009;119:565–572. doi: 10.1172/JCI37865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nistala K, Adams S, Cambrook H, et al. Th17 plasticity in human autoimmune arthritis is driven by the inflammatory environment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:14751–14756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003852107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sfanos KS, Bruno TC, Maris CH, et al. Phenotypic Analysis of Prostate-Infiltrating Lymphocytes Reveals TH17 and Treg Skewing. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14:3254–3261. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muranski P, Boni A, Antony PA, et al. Tumor-specific Th17-polarized cells eradicate large established melanoma. Blood. 2008;112:362–373. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-120998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hinrichs CS, Kaiser A, Paulos CM, et al. Type 17 CD8+ T cells display enhanced antitumor immunity. Blood. 2009;114:596–599. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-203935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin-Orozco N, Muranski P, Chung Y, et al. T Helper 17 Cells Promote Cytotoxic T Cell Activation in Tumor Immunity. Immunity. 2009;31:787–798. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paulos CM, Carpenito C, Plesa G, et al. The Inducible Costimulator (ICOS) Is Critical for the Development of Human TH17 Cells. Science Translational Medicine. 2010;2:55ra78. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garcia-Hernandez MdlL, Hamada H, Reome JB, et al. Adoptive Transfer of Tumor-Specific Tc17 Effector T Cells Controls the Growth of B16 Melanoma in Mice. The Journal of Immunology. 2010;184:4215–4227. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muranski P, Borman ZA, Kerkar SP, et al. Th17 Cells Are Long Lived and Retain a Stem Cell-like Molecular Signature. Immunity. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamai A, Pignon P, Raimbaud I, et al. Human Th17 immune cells specific for the tumor antigen MAGE-A3 convert to IFN-γ secreting cells as they differentiate into effector T cells in vivo. Cancer Research. 2012 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wainwright DA, Sengupta S, Han Y, et al. The Presence of IL-17A and T Helper 17 Cells in Experimental Mouse Brain Tumors and Human Glioma. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cantini G, Pisati F, Mastropietro A, et al. A critical role for regulatory T cells in driving cytokine profiles of Th17 cells and their modulation of glioma microenvironment. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2011;60:1739–1750. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1069-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwartzbaum JA, Huang K, Lawler S, et al. Allergy and inflammatory transcriptome is predominantly negatively correlated with CD133 expression in glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology. 2010;12:320–327. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu J, Mao Y, Li M, et al. The profile of Th17 subset in glioma. International Immunopharmacology. 2011;11:1173–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou P, Sha H, Zhu J. The Role of T-helper 17 (Th17) Cells in Patients with Medulloblastoma. The Journal of International Medical Research. 2010;38:611–619. doi: 10.1177/147323001003800223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]