Abstract

A highly efficient protein bioconjugation method is described involving the addition of anilines to o-aminophenols in the presence of sodium periodate. The reaction takes place in aqueous buffer at pH 6.5 and can reach high levels of completion in 2–5 min. The product of the reaction has been characterized using X-ray crystallography, which revealed that an unprecedented oxidative ring contraction occurs after the coupling step. The compatibility of the reaction with protein substrates has been demonstrated through the attachment of small molecules, polymer chains, and peptides to p-aminophenylalanine residues introduced into viral capsids through amber stop codon suppression. The coupling of anilines to o-aminophenol groups derived from tyrosine residues is also described. The compatibility of this method with thiol modification chemistry is shown through the attachment of a near-IR fluorescent chromophore to cysteine residues inside the viral capsid shells, followed by the attachment of integrin-targeting RGD peptides to anilines on the exterior surface.

Keywords: Bioconjugation, protein modification, Click reactions, viral capsids, targeted delivery agents

The chemical modification of proteins1 is a crucial tool for the study of biochemical function2 and for the scalable synthesis of biomolecular materials,3 targeted imaging agents,4 and protein-drug conjugates.5 As the applications of bioconjugates become ever more complex, an expanded set of chemical strategies is needed to add new functionality to specific locations with high chemoselectivity and yield. In most cases to date, site specific protein labeling has been achieved by targeting cysteine residues,1 taking advantage of the highly nucleophilic character of thiolate anions and their particularly low abundance on the surfaces of most proteins. Useful as this chemistry is, however, there are still many circumstances that require additional chemical reactions to install a second set of functional groups or to avoid alkylating native cysteine groups that are required for protein function. As an example from our own lab, we have used cysteine-based strategies to install drug6 and imaging cargo7 inside genome-free viral capsids for applications in targeted delivery. What has been more difficult, however, is the installation of peptides8 and nucleic acid aptamers9 on the external surface that can bind to specific receptors on tumor tissue. We and others10 have found that “bioorthogonal” protein modification reactions11 are particularly useful in these situations, as they can target ketone,12 azide,13 alkyne,14 and aniline15 groups specifically while ignoring native protein functionality. The functional groups required for these reactions can be introduced as unnatural amino acids,16 or they can be installed using more traditional bioconjugation reactions. However, many of the existing reactions proceed at low coupling rates or require high concentrations of reactants that are often in short supply. The growing complexity of the protein bioconjugates that are sought creates a need for additional reactions that can proceed with increased levels of efficiency and yield.

To provide new opportunities for site-selective protein bioconjugation with highly functionalized substrates, we have previously explored a new class of oxidative couplings between aniline side chains and N-acylphenylene diamine groups in the presence of sodium periodate, Figure 1a.17 This method yields hydrolytically stable “A+B” products with excellent chemoselectivity, and has been used to attach peptides,8 nucleic acids,9,6b and porphyrins18 (as R2 groups in 2) to p-aminophenylalanine (pAF) side chains (1b) introduced using amber stop codon suppression.15 After completing a series of optimization studies, we now report a substantially more efficient version of this reaction involving the addition of anilines to o-aminophenols (4) under similar oxidizing conditions, Figure 1b. This new reaction proceeds to very high levels of conversion in well under 2 min, yielding stable protein bioconjugates with equivalent chemoselectivity. We introduce the functional groups required for this reaction either by modifying native tyrosine residues or through the direct incorporation of artificial amino acids. The high speed of this coupling reaction makes it well suited for assembling multicomponent structures from building blocks at low concentrations, or for achieving protein modification in situations that are particularly time-sensitive, such as radiolabeling.

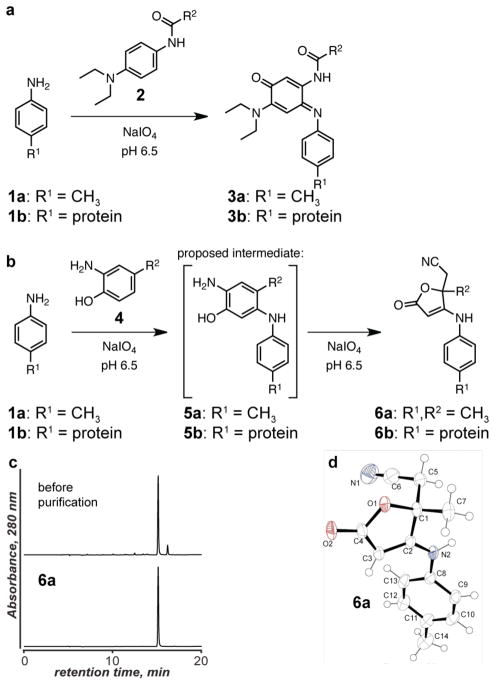

Figure 1.

Oxidative coupling reactions involving aniline groups on proteins. (a) The previously reported coupling between anilines and phenylene diamines occurs within 30–60 min. (b) The coupling between anilines and aminophenols occurs much faster, reaching high levels of conversion in under 2 min. (c) Reverse phase HPLC of 6a before and after purification indicated that the isolated compound was the major product in the reaction. (d) Product 6a was characterized using X-ray diffraction analysis.

The appropriate reaction conditions and product structure of this new coupling method were determined through small molecule studies. It was found that 2-amino-4-methylphenol (4) reacted with one equivalent of p-toluidine (1a) in the presence of ten equivalents of sodium periodate19 in pH 6.5 phosphate buffer, Figure 1b. In under 5 min, a single major product was obtained in 40% isolated yield, and HPLC analysis of the crude mixture suggested that excellent conversion had been obtained, Figure 1c. The low yield of the isolated product was attributed to incomplete extraction of the compound from the dilute aqueous solution in which it was generated, as no other major products were evident. The product was identified as compound 6a using NMR and X-ray diffraction analysis of an obtained crystal. The 13C NMR spectrum showed a clear nitrile signal at 115.6 ppm, and IR analysis showed an absorption band at 2218 cm−1. The X-ray data matched structure 6a with a goodness-of-fit of 1.05, leaving no doubt as to the nature of the obtained product. We presume that this structure was formed through the oxidation of 2-amino-4-methylphenol to the o-iminoquinone species, although single-electron coupling pathways can also be considered as plausible mechanisms. Addition of the aniline to the 5-position of the iminoquinone would yield postulated intermediate 5a, which can be converted into the observed product through a second oxidation of the aminophenol, water addition, and amino alcohol cleavage by the periodate. This breaks the six membered ring and ultimately forms the nitrile group (see Supporting Information Figure S1 for our current mechanistic hypotheses). The ability of this reaction to reach high conversion under mild conditions and at sub-mM concentrations in aqueous buffer suggested that it would perform similarly well using protein substrates. Although several unidentified dyestuffs accompany the reaction product in trace amounts, 6a is obtained with surprisingly high efficiency for such a complex reaction pathway.

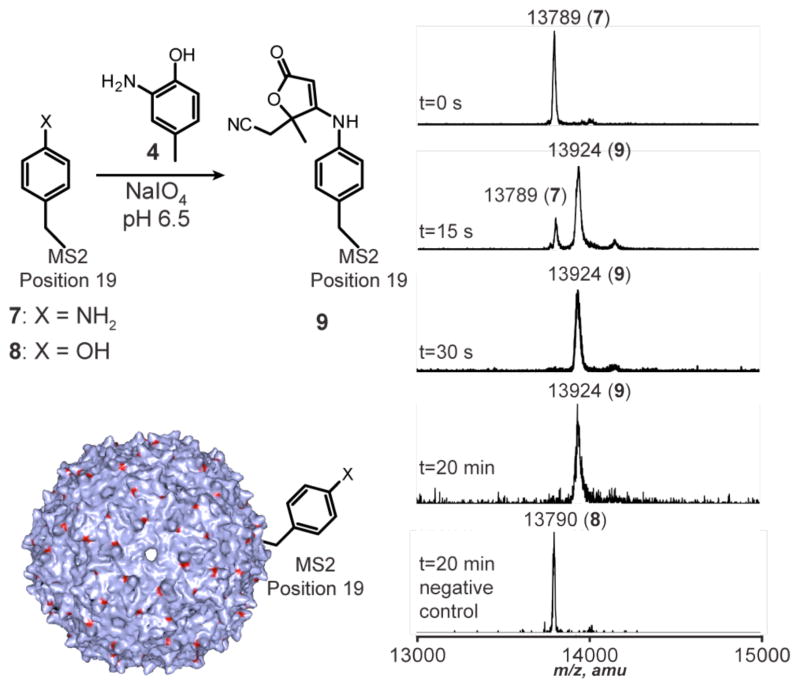

To evaluate this reaction on a protein substrate, we next introduced the aniline groups on the external surface of genome-free MS2 capsids.8 To do this, we introduced p-aminophenylalanine (pAF) into position 19 of each protein monomer using an amber stop codon suppressor tRNA/aminoacyl tRNA synthetase pair developed by the Schultz lab.15 The small molecule model reaction shown in Figure 1b was then repeated with T19pAF MS2 (7) as the aniline component. 2-Amino-4-methylphenol (4, 100 μM) was combined with 7 (30 μM in monomer, 167 nM in capsid) in pH 6.5 phosphate buffer at room temperature. A 50 mM solution of freshly prepared sodium periodate was then added to achieve a final concentration of 1 mM. Aliquots were removed at various timepoints and quenched by the addition of tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP). Subsequent analysis using MALDI-TOF MS (following capsid disassembly during the sample preparation process) indicated complete conversion to a single new peak in 30 s, with no additional modification or degradation occurring during the next 20 min of reaction time, Figure 2. The mass change corresponded to the difference observed in the small molecule studies (including the water addition), indicating that the structure of the protein product was analogous to 6a. As a negative control, the reaction was repeated using an MS2 mutant bearing a tyrosine at position 19 (T19Y MS2, 8). This single atom change resulted in no observed product after 20 min of reaction, Figure 2. The lack of mass increase or broadening of the protein peak in this experiment indicated that background oxidation pathways were not occurring for native amino acid residues.

Figure 2.

Targeting an artificial amino acid through oxidative coupling. T19pAF MS2 (30 μM) was reacted with 2-amino-4-methylphenol (100 μM) in the presence of sodium periodate (1 mM). Aliquots were removed at various time points and quenched by the addition of tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP). Single protein modification was complete by 30 s. No additional modification was detected after 20 min. A negative control reaction using T19Y MS2 showed no modification under otherwise identical conditions.

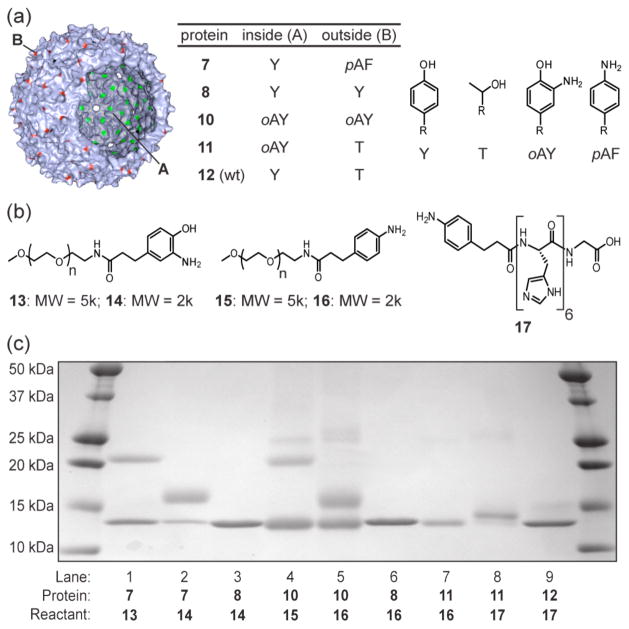

To generate more useful bioconjugates, we have used this oxidative coupling reaction to attach larger molecules to MS2 capsids with similar efficiency. As one example, o-aminophenol-terminated poly(ethylene glycol) chains (13 and 14) coupled readily to MS2 capsids bearing external pAF groups in 2 min, but not to proteins bearing only tyrosines in the same positions (Figure 3, lanes 1–3). According to optical densitometry of the Coomassie stained SDS-PAGE gel, approximately 65% of the pAF-containing monomers were modified when reacted with 13 and 75% were modified by 14. This corresponded to the installation of 117–135 copies of the PEG chains on each capsid. The decrease in modification percentage with the larger PEG chain is likely due to increased steric congestion as high levels of modification are approached. As an initial test of this reaction on another protein substrate, we have found that aminophenol polymer 14 couples with similar efficiency to an aniline labeled sample of lysozyme (see Supporting Information Figure S8 for details).

Figure 3.

A panel of reactants was exposed to the MS2 capsids listed in (a), which presented phenol, o-aminophenol (oAY), or aniline (pAF) groups in varying combinations. Each reaction contained 30 μM protein, a coupling partner selected from (b) at 200–500 μM, and NaIO4 (1 mM for lanes 1–7, 5 mM for lanes 8 and 9). Each reaction time was 2 min, after which the samples were quenched with loading buffer and analyzed via SDS-PAGE.

The coupling of macromolecules to o-aminophenol-containing MS2 was also investigated. In a previous study,20 we had found that the aminophenol groups introduced inside MS2 using a diazonium coupling/dithionite reduction procedure could be oxidized in the presence of sodium periodate to yield a species that coupled to p-aminophenyl acrylamide. Using the information and protein characterization methods that were available to us at the time, we originally assigned this product as the hetero-Diels-Alder cycloaddition product between the oxidized aminophenol group and the acrylamide dienophile.21 It now appears that the reaction involved the unanticipated addition of the aniline group to the aminophenol as described herein. However, the mass change reported in the previous paper corresponded more closely to an analog of 5a, rather than 6a. To verify this, the previously reported conditions (100 μM sodium periodate, pH 6.5, 2 h) were repeated on a peptide substrate using p-toluidine as the coupling partner (see Supporting Information for synthetic details). The mass difference of the product was indeed similar to that of proposed adduct 5a (Supporting Information Figure S4f), but corresponded to 6a using the 1–5 mM periodate conditions reported in this work (Figure S4e). Despite numerous attempts, we have been unable to isolate intermediate 5a in our small molecule studies, presumably due to its facile oxidation. Thus, the exact nature of the 1:1 protein modification product using low concentrations of periodate is still unknown.

Capsids bearing aminophenol groups on the internal (11) or internal and external (10) surfaces were generated as described in the Supporting Information. For these experiments, 5 kDa and 2 kDa monomethoxy PEG anilines 15 and 16 were synthesized, as well as peptide aniline 17. Under identical reaction conditions, the peptide aniline coupled to the internal surface of MS2-o-aminophenol-85 capsids (11) in high yield, as determined by MALDI-MS and SDS-PAGE (Figure 3, lane 8, and Supporting Information Figure S2). Interestingly, neither of the PEG anilines coupled to 11 (shown for 2k-PEG substrate 16 in lane 7), likely because they were too large to pass through the 1.8 nm pores22 and access the o-aminophenol at position 85 on the inner surface of the capsids. However, coupling of PEG-aniline to the bis(o-aminophenol)-MS2 capsids (10) showed significant conversion to the single polymer conjugate (lanes 4 and 5). Optical densitometry of the Coomassie stained gel indicated a conversion of 40% with 15 and 50% with 16. These numbers were lower than the above case presumably because the chemical modification of tyrosine to o-aminophenol does not proceed to completion, while the genetically introduced p-aminophenylalanine groups are present in all monomers. It was further observed that small amounts of MS2 dimers were obtained when the aminophenol groups were present on the protein component (see faint upper bands in lanes 4, 5, and 8). This minor pathway could occur through the addition of adjacent protein nucleophiles under the high local concentration conditions, or through the dimerization of the aminophenol groups. Though this corresponds to fewer than 10% of the protein monomers, it still seems more practical to include the aniline group on the protein component.

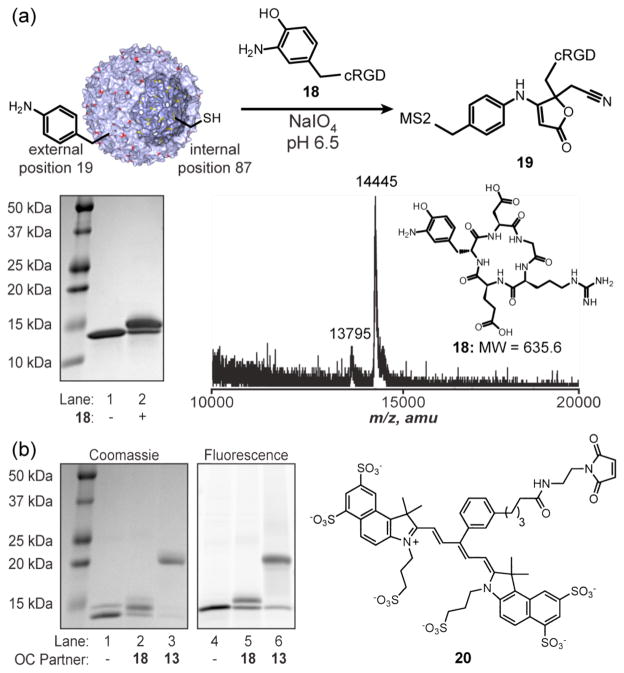

After confirming the ability of this coupling reaction to attach new functional groups to either capsid surface, we next used it to prepare a protein conjugate with practical applications. Cyclic RGD is a widely used peptide for the binding of integrin αVβ3.23 A five amino acid version of cyclic RGD was converted to the corresponding o-aminophenol (18) via reaction with tetranitromethane and subsequent reduction with sodium dithionite (see Supporting Information Scheme S1). Compound 18 (120 μM) was then coupled to T19pAF MS2 (30 μM in monomer) in the presence of 5 mM sodium periodate at pH 6.5. SDS-PAGE and MALDI-TOF analysis of the MS2 coat protein monomers showed excellent conversion to the peptide conjugate (Figure 4a), with densitometry analysis indicating that 65% of the monomers had been modified. The resulting capsids therefore had approximately 117 copies of the peptide attached in 5 min.

Figure 4.

Attachment of a cyclic RGD peptide to T19pAF MS2. (a) Compound 18 (200 μM) was exposed to T19pAF MS2 (30 μM) in the presence of sodium periodate (5 mM) for 2 min. MS2 capsids were disassembled into monomers for analysis via SDS-PAGE and MALDI-TOF. Expected masses are m/z 13795 for Tl9pAF MS2 and m/z 14443 for 19. (b) MS2 capsids bearing internal cysteines (N87C, yellow) and external pAF19 groups (red) were labeled with NIR dye 20. Following disassembly, the samples were analyzed by SDS–PAGE (lanes 1 and 4). Coomassie staining is shown on the left and fluorescence imaging of 20 is shown on the right. Portions of the capsids were then externally labeled with 18 (290 μM, lanes 2 and 5) or 13 (220 μM, lanes 3 and 6) upon exposure to 5 mM periodate for 5 min.

We believe the chemoselectivity of this reaction stems from the lack of potent nucleophiles at neutral pH on most proteins, in combination with the short reaction times that are required. Free thiols would be the obvious exception to this, and therefore we recommend first labeling cysteine residues with a desired functional group, or temporarily capping them as asymmetric disulfides before carrying out the oxidative coupling step. As with any reaction involving sodium periodate, there is a possibility of N-terminal serine cleavage, carbohydrate oxidation, and methionine oxidation. However, we have not observed these pathways in the present study.

As an example of the compatibility of this chemistry with cysteine labeling, we have prepared MS2 capsids bearing near IR dyes on the internal surface and cRGD peptides or PEG on the exterior. To do this, MS2 capsids bearing cysteine residues in position 87 and pAF residues in position 19 were prepared using the amber codon suppression technique and exposed to maleimide chromophore 20 in pH 6.5 phosphate buffer.9 SDS-PAGE analysis indicated that 20% of the interior cysteine residues had been modified with the bulky group (previous studies in our lab have shown that pAF19 MS2 capsids lacking the cys87 groups are unreactive toward maleimide reagents under these conditions9). Separate samples of the chromophore labeled capsids were then exposed to cRGD-aminophenol 18 and 5k-PEG-aminophenol 13 for 5 min in the presence of periodate. Analysis using SDS-PAGE indicated excellent conversion to the externally labeled products in both cases, and fluorescence imaging clearly indicated the presence of monomers that were labeled with both the chromophores and the external groups, Figure 4b. Analysis of the resulting capsids using SEC indicated that no disassembly had occurred during this procedure (see Supporting Information, Figure S5).

Through these studies we have developed a rapid, chemoselective reaction for the coupling of anilines to aminophenols. We demonstrated that the reaction conditions are mild enough to modify proteins under non-denaturing conditions and showed its capability to attach cancer targeting groups to viral capsids that contain optical imaging cargo. The efficiency of this coupling technique has great promise for building a number of complex protein-based materials, and it is currently being explored for this purpose. We working to elucidate the mechanism of this unprecedented coupling reaction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by the NIH (GM 072700). CRB was supported by DOE CARE (California Alliance for Radiotracer Education) grant DESC0002061, and ACO was supported by an NSF graduate research fellowship. The UC Berkeley Chemical Biology Graduate Program (Training Grant 1 T32 GMO66698) is also acknowledged for their support of CRB, DWR, and ACO.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Full experimental procedures and characterization data are available as supporting information. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Hermanson GT. Bioconjugate Techniques. 2. Academic Press; San Diego: 2008. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tilley SD, Joshi NS, Francis MB. Wiley Encyclopedia of Chemical Biology. Wiley-VCH; 2008. Proteins: Chemistry and Chemical Reactivity. [Google Scholar]

- 2.For some interesting lead examples, see: Joo C, Balci H, Ishitsuka Y, Buranachai C, Ha T. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:51–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.070606.101543.Evans MJ, Cravatt BF. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3279–3301. doi: 10.1021/cr050288g.Cecconi C, Shank EA, Bustamante C, Marqusee S. Science. 2005;309:2057–2060. doi: 10.1126/science.1116702.Muir TW, Sondhi D, Cole PA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6705–6710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6705.Valiyaveetil FI, Sekedat M, MacKinnon R, Muir TW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17045–17049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407820101.Cooper JA, Walker SB, Pollard TD. J Mus Res Cell Motil. 1983;4:253–262. doi: 10.1007/BF00712034.

- 3.(a) Wang P, Sergeeva MV, Lim L, Dordick JS. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:789–793. doi: 10.1038/nbt0897-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nam YS, Magyar AP, Lee D, Kim J, Yun DS, Park H, Pollom TS, Weitz DA, Belcher AM. Nat Nanotech. 2010;5:340–344. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Day JJ, Marquez BV, Beck HE, Aweda TA, Gawande PD, Meares CF. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alley SC, Okeley NM, Senter PD. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:529–537. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.06.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Wu W, Hsiao SC, Carrico ZM, Francis MB. Angew Chemie Int Ed. 2009;48:9493–9497. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stephanopoulos N, Tong GJ, Hsiao SC, Francis MB. ACS Nano. 2010;4:6014–6020. doi: 10.1021/nn1014769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Hooker JM, Datta A, Botta M, Raymond KN, Francis MB. Nano Lett. 2007;7:2207–2210. doi: 10.1021/nl070512c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Meldrum T, Seim KL, Bajaj VS, Palaniappan K, Wu W, Francis MB, Wemmer DE, Pines A. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5936–5937. doi: 10.1021/ja100319f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrico ZM, Romanini DW, Mehl RA, Francis MB. Chem Commun. 2008:1205–1207. doi: 10.1039/b717826c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tong GJ, Hsiao SC, Carrico ZM. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:11174–11178. doi: 10.1021/ja903857f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strable E, Prasuhn DE, Jr, Udit AK, Brown S, Link AJ, Ngo JT, Lander G, Quispe J, Potter CS, Carragher B, Tirrell DA, Finn MG. Bioconj Chem. 2008;19:866–875. doi: 10.1021/bc700390r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sletten EM, Bertozzi CR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:6974–6998. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornish VW, Hahn KM, Schultz PG. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:8150–8151. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deiters A, Cropp TA, Mukherji M, Chin JW, Anderson JC, Schultz PG. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11782–11783. doi: 10.1021/ja0370037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Link AJ, Tirrell DA. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11164–11165. doi: 10.1021/ja036765z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehl RA, Anderson JC, Santoro SW, Wang L, Martin AB, King DS, Horn DM, Schultz PG. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:935–939. doi: 10.1021/ja0284153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Wang L, Schultz PG. Chem Commun. 2002:1–11. doi: 10.1039/b108185n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kiick KL, Tirrell DA. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:9487–9493. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hooker JM, Esser-Kahn AP, Francis MB. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15558–15559. doi: 10.1021/ja064088d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephanopoulos N, Carrico ZM, Francis MB. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:9498–9502. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.For examples of other bioconjugation reactions involving sodium periodate, see: Geoghegan KF, Stroh JG. Bioconj Chem. 1992;3:138–146. doi: 10.1021/bc00014a008.Liu B, Burdine L, Kodadek T. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15228–15235. doi: 10.1021/ja065794h.

- 20.Hooker JM, Kovacs EW, Francis MB. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3718–3719. doi: 10.1021/ja031790q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nair V, Mathew B. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:11017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valegard K, Liljas L, Fridborg K, Unge T. Nature. 1990;345:36–41. doi: 10.1038/345036a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.For other examples of viral capsids bearing tissue-specific targeting groups, see: Suci PA, Varpness Z, Gillitzer E, Douglas T, Young M. Langmuir. 2007;23:12280–12286. doi: 10.1021/la7021424.Banerjee D, Liu A, Voss NR, Schmid S, Finn MG. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:1273–1279. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000125.Mastico RA, Talbot SJ, Stockley PG. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:541–548. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-4-541.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.