Abstract

The C-alkylation of nitroalkanes under mild conditions has been a significant challenge in organic synthesis for more than a century. Herein, we report a simple Cu(I) catalyst, generated in situ, that is highly effective for C-benzylation of nitroalkanes using abundant benzyl bromides and related heteroaromatic compounds. This process, which we believe proceeds via a thermal redox mechanism, allows access to a variety of complex nitroalkanes under mild reaction conditions and represents the first step towards developing a general catalytic system for the alkylation of nitroalkanes.

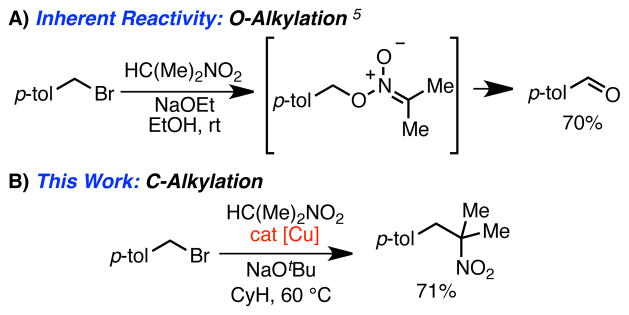

Nitroalkanes are ubiquitous reagents in organic synthesis. They are widely used as synthons for heterocycles, as radical precursors, and for heteroatom installation, including carbonyls via the Nef reaction and amines via reduction. Arguably, their most important function is serving as nucleophiles for carbon-carbon (C–C) bond construction. Although a number of reactions involving C–C bond-formation of nitroalkanes are known, including the Henry reaction,1 conjugate additions to α,β-unsaturated carbonyls,1 and palladium-catalyzed allylation2 and arylation reactions,3 the alkylation of nitroalkanes with alkyl halide electrophiles to form a new C–C bond remains a significant challenge. As early as 1908, failures of attempted C-alkylation reactions were first reported.4 In 1949, Hass and Bender reported a detailed investigation that explained the failure; treatment of nitronate anions with a variety of alkyl halides results in O-alkylation, ultimately leading to the formation of carbonyl products via nitronic esters (Scheme 1A).5 Only minor amounts of C-alkylated products are formed. The O-alkylation pathway predominates with both benzylic and aliphatic halides and with nitronate anions derived from nitromethane, primary and secondary nitroalkanes. The one exception is for ortho- or para-nitrobenzyl chloride electrophiles, which were found to react with nitronate anions at carbon.5 This unique reactivity was later shown by Kornblum and co-workers to proceed via a Srn1 pathway triggered by single electron transfer (SET) from the nitronate anion to the highly electron-deficient aromatic ring.6 However, except for this mechanistically isolated case, C-alkylation of simple nitronate anions does not occur with alkyl halide electrophiles.

Scheme 1.

Alkylation of Nitronate Anions.

Previous systems to achieve C-alkylation of nitroalkanes require either the formation of nitronate dianions at inconveniently low (−90 °C) temperature7 or the use of complex 2,4,6-trisubstituted N-alkyl pyridinium ions as electrophiles (this latter reaction also proceeds via an Srn1 pathway).8 Both of these methods have serious limitations in preparative chemistry. A procedure using readily available alkyl halides to C-alkylate nitroalkanes under mild reactions conditions would greatly expand both the preparation and utility of nitroalkanes in organic synthesis.

In this communication, we report the first step towards a practical solution to this century-old problem. We disclose the development of conditions for the benzylation of nitroalkanes using electron-rich Cu(I) catalysts (Scheme 1B). These reactions occur at mild temperature (60 °C), employ benzyl bromides and inexpensive precatalysts, and afford high yields. We believe that these reactions proceed via a thermal redox catalysis pathway. Importantly, this process is very general with respect to both the benzyl bromide and nitroalkane, including the use of secondary nitroalkanes. This wide scope allows preparation of a variety of complex nitroalkanes. In addition, this method enables facile preparation of phenethylamine derivatives, which are important medicinal agents.

In considering means to effect the C-alkylation of nitroalkanes, we were particularly drawn to the potential use of radical chemistry. In addition to the radical pathways elucidated by Kornblum6 and Katritzky,8 photogenerated alkyl radicals, generated via the homolytic fragmentation of mercury- or cobalt-alkyls, have been shown to react with nitronate anions at carbon.9 Although of limited synthetic utility, these reactions demonstrate that radical-anion coupling involving nitronate anions is feasible.

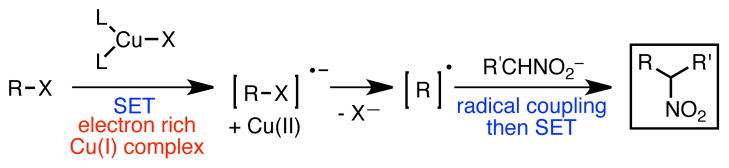

Simultaneously, we were cognizant of recent work in the area of metal-catalyzed alkylation of carbon nucleophiles using alkyl halides.10 Many of these reactions have been shown to involve radical intermediates. We were particularly drawn to the copper-based catalyst systems used in the mechanistically related Atom Transfer Radical Addition (ATRA) and Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization (ATRP) reactions, in which Cu(I) catalysts initiate radical reactions of substituted alkenes by undergoing a SET reaction with alkyl halides bearing a wide range of radical stabilizing groups.11 Given the propensity of nitronate anions to undergo reactions with radical intermediates, we reasoned that a copper-based catalyst might promote C-alkylation using readily prepared or commercially available alkyl halides via a pathway involving SET followed by radical-anion coupling (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Electron-rich Copper Catalysts to Promote Nitroalkane Alkylation.

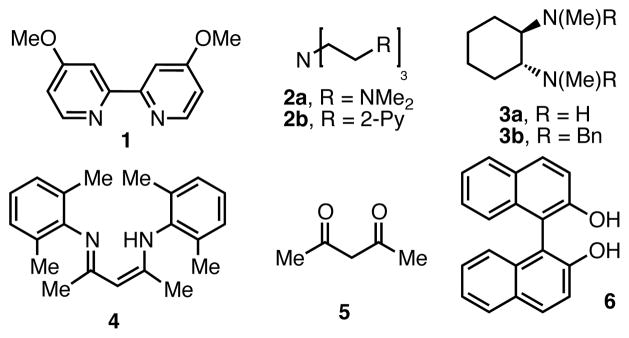

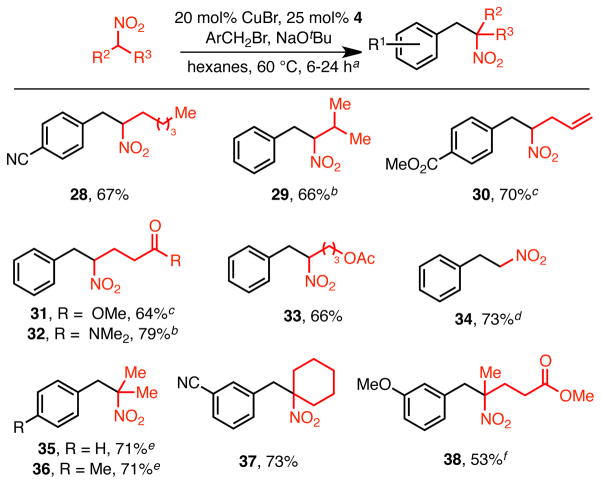

We began our investigation by examining the reaction of 1-nitropropane and benzyl bromide in benzene. Under basic conditions in the absence of catalyst, only trace desired 1-phenyl-2-nitrobutane (7) was observed (<5% by NMR). The major product in these reactions was benzaldehyde (12% by NMR, Table 1, entry 1) along with unreacted starting material. Attempts to employ catalysts derived from palladium, cobalt, nickel or iron lead to similar results (not shown). With the use of CuBr, and simple ligands such as PPh3 or bipyridyl 1, a modest increase in the desired product was seen (entries 2 and 3). Interestingly, the neutral polydentate ligands 2a and 2b, which are often very effective ligands in ATRA/ATRP reactions, were less effective (entries 4 and 5).

Table 1.

Identification of Reaction Conditions.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | ligand | base | solvent | yield 7b | yield 8b |

| 1 | nonec | KOtBu | C6D6 | trace | 12% |

| 2 | PPh3 | KOtBu | C6D6 | 18% | 13% |

| 3 | 1 | KOtBu | C6D6 | 17% | 19% |

| 4 | 2a | KOtBu | C6D6 | 8% | 14% |

| 5 | 2b | KOtBu | C6D6 | 10% | 2% |

| 6 | 3a | KOtBu | C6D6 | 45% | 8% |

| 7 | 3b | KOtBu | C6D6 | 15% | 22% |

| 8 | 4 | KOtBu | C6D6 | 64% | 2% |

| 9 | 5 | KOtBu | C6D6 | 3% | 10% |

| 10 | 6 | KOtBu | C6D6 | 7% | 8% |

| 11d | 4 | KOtBu | C6D6 | 72% | 2% |

| 12d | 4 | LiOtBu | C6D6 | 0% | 1% |

| 13d | 4 | NaOtBu | C6D6 | 78% | 2% |

| 14d | 4 | NaOtBu | hexanes | 85%e | trace |

Unless otherwise noted: 1.15 equiv nitropropane;

Unless otherwise noted: yields determined by NMR;

No copper, no ligand;

Conditions: 1.25 equiv nitropropane, 1.2 equiv base, 25 mol% 4;

Isolated yield.

In contrast, trans-N,N′-dimethyl-1,2-cyclohexanediamine (3a), a ligand that has been used in copper-catalyzed Goldberg-type reactions12 but not often used in atom-transfer reactions, led to more promising results. Using this ligand, 7 was observed in 45% yield (entry 6). Unfortunately, efforts to optimize this ligand design were unsuccessful. However, during these studies we noted a major byproduct from the reaction was the dibenzylated ligand 3b. Independent preparation of 3b revealed that it was ineffective as a ligand in the catalytic reaction (entry 7).13 Similar results were observed for other tetra-alkyl diamine ligands, leading us to speculate that the protic N–H bond of 3a might be integral to its success in the reaction; we postulated that the active catalyst might arise from deprotonation of the ligand under the reaction conditions leading to the formation of a highly electron-rich Cu(I)-amido species.

This line of reasoning led us to examine the use of 1,3-diketimine (nacnac) ligands in the reaction. We predicted that the acidic nature of the nacnac backbone would rapidly result in the formation of a neutral Cu(I)-nacnac under the basic reaction conditions.14 Further, we hoped that the steric bulk of the nacnac architecture would prevent competitive alkylation of the ligand. Using nacnac 4, a 64% yield of 7 was observed under the initial screening conditions. Extensive attempts to optimize the reaction through modulation of the nacnac framework proved unsuccessful (see Supporting Information); however further studies revealed a significant effect of the base counter-ion, with sodium proving optimal in terms of yield and ease of use (entry 12 vs. 13).15,16 Non-polar solvents were also generally favored, with hexanes being the most effective in the screening reaction. Using these optimized conditions, the desired 2° nitroalkane could be isolated in 85% yield on a 1 mmol scale (entry 14).17

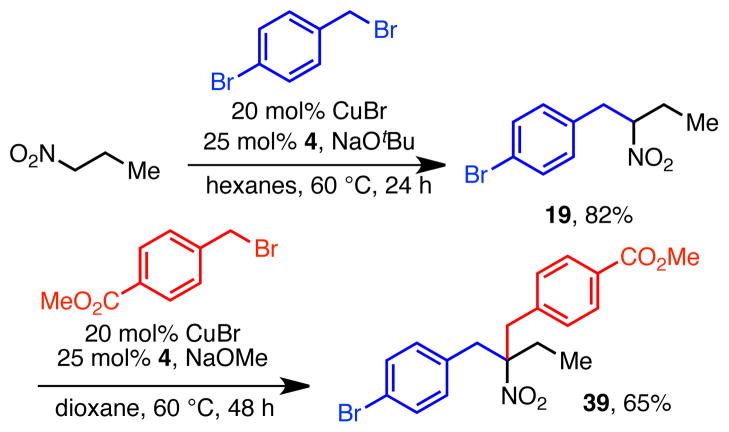

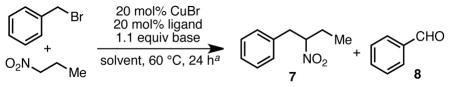

The scope of the reaction with respect to benzyl bromide is broad (Table 2). A wide-range of functional groups are tolerated, including fluorides, chlorides, bromides, nitriles, esters, ethers, and tri-fluoromethyl groups. Both electron-rich (13) and electron-poor (14, 20, and 21) benzyl bromides participate in the reaction, and there is remarkably little variance in the yield of product due to the electronic effects of the arene substituent. The reactions of more sterically encumbered benzyl bromides, such as those containing an ortho methyl group (10), and polyaromatic substrates (23) also proceed without incident. Para-nitrobenzyl bromide also reacts to provide the C-alkylated product under the copper-catalyzed reaction conditions (22).5 Finally, bromomethyl-substituted hetereoaromatic compounds also can be used in the reaction. For example, treatment of 2-bromomethylpyridine hydrobromide with 1-nitropropane lead to nitropyridine 24. Other heteroaromatics, including quinolones (25), thiophenes (26), and benzoxazoles (27) are also efficient substrates.18 The reaction was easily scaled; compound 19 was isolated in 82% yield from a 2.5 gram reaction. In all cases, only trace amounts aldehyde (1–5%) were observed. The major byproduct detected (NMR and GC) was the bibenzyl resulting from dimerization of the alkylating reagent.

Table 2.

Scope with Respect to Benzyl Bromides.

|

Unless otherwise noted, conditions: 1 equiv benzyl bromide, 1.25 equiv 1-nitropropane, 20 mol% CuBr, 25 mol% 4, 1.2 equiv NaOtBu;

Base = NaOMe;

2.2 equiv of NaOtBu, solvent = benzene; starting material = HCl salt;

Solvent = benzene, base = NaOSiMe3.

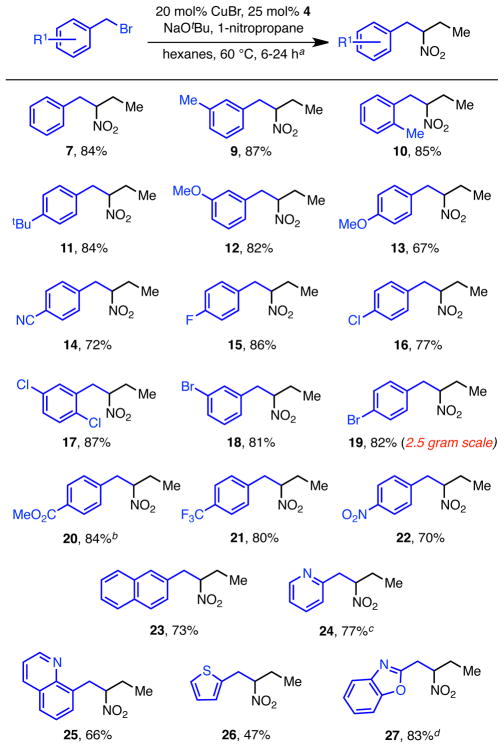

The reaction also enjoys wide substrate scope with respect to the nitroalkane (Table 3). Longer aliphatic nitroalkanes, such as nitrohexane, participated in the reaction well (28). Branching beta to the nitro group was tolerated (29). A range of functional groups on the nitroalkane proved compatible with the transformation, including alkenes, esters, amides and acyl-protected alcohols (30–33). All of these reactions proceeded in good yield under the standard reaction conditions or slight modifications thereof. Nitromethane can also be alkylated using this catalyst system in good yield (73%, 34), provided it is used in excess (7.5 equiv). Under these conditions, good selectivity for the monoalkylated product is observed; with less nitromethane double alkylation competes.

Table 3.

Scope with Respect to Nitroalkanes.

|

Unless otherwise noted, conditions: 1 equiv benzyl bromide, 1.25 equiv 1-nitroalkane, 20 mol% CuBr, 25 mol% 4, 1.2 equiv NaOtBu;

Solvent = dioxane;

Base = NaOMe;

20 mol% CuBr, 20 mol% 4, 7.5 equiv NO 2Me, solvent = dioxane;

1.15 equiv nitroalkane, 20 mol% 4, solvent = cyclohexane, 48 h;

1.15 equiv nitroalkane, solvent = cyclohexane, base = NaOSiMe 3, 24 h, reaction performed in glovebox.

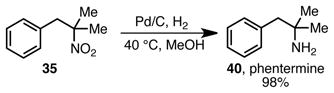

Importantly, secondary nitroalkanes are also tolerated in the reaction. For example, benzylation of 2-nitropropane resulted in a 71% isolated yield of 35 (Table 3). This transformation allows for the direct construction of a fully substituted carbon bearing a nitrogen substituent, which remains a challenging problem in organic synthesis.19 Not surprisingly, this reaction proceeded more slowly than those employing primary nitroalkanes. Interestingly, however, this reaction was very sensitive to the choice of solvent, and cyclohexane provided consistently higher yields than hexanes, which was employed in the other reactions. The reason for this solvent effect is not clear – no additional byproducts, such as reduced starting materials, were detected. Other secondary nitroalkanes can participate in the reaction, including nitrocyclohexane (37) and those bearing functional groups (38).20

The ability of secondary nitroalkanes to participate in the reaction opens the possibility for sequential alkylation reactions (Scheme 3). For example, as reported above, alkylation of nitropropane with 4-bromobenzyl bromide gave rise to nitroalkane 19 in 82% yield. Subsequent alkylation of that product with methyl 4-(bromomethyl)-benzoate resulted in tertiary nitroalkane 39 in 65% yield. Such sequential alkylation reactions promise the ability to rapidly prepare complex nitroalkanes and amines from very simple starting materials.

Scheme 3.

Sequential Double Benzylation of Nitroalkanes.

There is clear relevance of the nitroalkane products from the copper-catalyzed benzylation reaction to the preparation of bioactive molecules. Phenethylamines are important medicinal agents, which have found wide use in the treatment of obesity and other metabolic diesases.21 These compounds can be readily prepared from β-phenyl nitroalkanes.1 As an illustration of the utility of our catalytic process, simple hydrogenolysis of nitroalkane 35 provided the tertiary amine phentermine (40) in high yield. Phentermine is a clinically prescribed anorectic (appetite suppressant) for the treatment for obesity.22 It is typically prepared via the Henry reaction of benzaldehyde and 2-nitropropane followed by a multi-step reduction sequence,23 or via a Ritter reaction of the corresponding tertiary alcohol and subsequent hydrolysis,24 both of which require more steps than the sequence reported herein.

|

(1) |

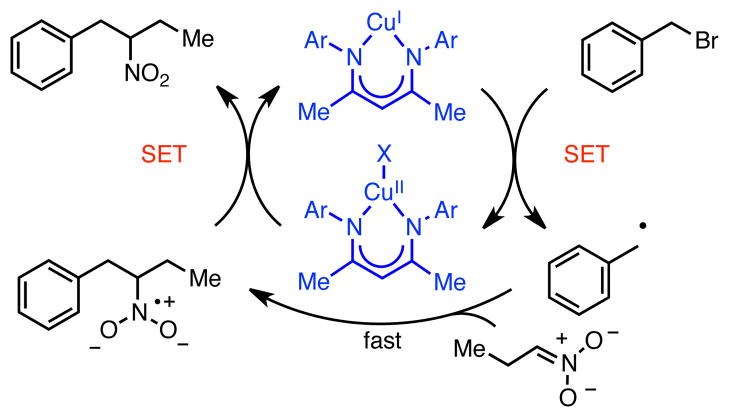

Mechanistically, we postulate that these reactions are proceeding via a thermal redox mechanism involving single electron transfer (SET) from the electron-rich copper catalyst to the benzyl bromide (Scheme 4). Upon loss of halide, this process would generate a neutral benzylic radical, which could undergo coupling with the nitronate anion. Electron transfer from the resulting nitronate radical would regenerate the copper catalyst, closing the catalytic cycle. The observation of bibenzyl side products is consistent with a single electron pathway.25

Scheme 4.

Possible Mechanistic Pathway.

In summary, we have developed a catalytic system for the benzylation of nitroalkanes that utilizes readily available benzyl halides and related hetereoaromatic compounds. This protocol addresses a century-old gap in C–C bond construction and provides the first example of alkylation of nitroalkanes using readily available starting materials under mild reaction conditions. This reaction allows for the conversion of simple starting materials to complex nitroalkanes, which are important synthetic intermediates in the preparation of bioactive molecules, such as phenethylamines. The key to this discovery was the identification of a highly electron-rich Cu(I)-nacnac complex, which can be prepared in situ and is capable of facile reduction of the benzyl halide to the corresponding radical. This thermally driven process clearly bears mechanistic resemblance to catalytic photoredox systems, the synthetic utility of which has been elegantly demonstrated by several groups.26,27 Efforts to expand our copper-based system to other types of catalytic redox reactions, as well as to expand the scope of the nitroalkane alkylation chemistry to other classes of alkyl halides, are currently underway in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Examples of Ligands Examined in the Benzylation.

Acknowledgments

The University of Delaware (UD) and the University of Delaware Research Foundation are gratefully acknowledged for funding and other research support. NMR and other data were acquired at UD on instruments obtained with the assistance of NSF and NIH funding (NSF MIR 0421224, NSF CRIF MU CHE0840401, NIH P20 RR017716, NIH S10 RR02692).

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Experimental procedures, spectral data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Ono N. The Nitro Group In Organic Synthesis. John Wiley And Sons; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Aleksandrowicz P, Piotrowska H, Sas W. Tetrahedron. 1982;38:1321. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wade PA, Morrow SD, Hardinger SA. J Org Chem. 1982;47:365. [Google Scholar]; (c) Tsuji J, Yamada T, Minami I, Yuhara M, Nisar M, Shimizu I. J Org Chem. 1987;52:2988. [Google Scholar]; (d) Trost BM, Surivet JP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:3122. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000901)39:17<3122::aid-anie3122>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Maki K, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:4250. [Google Scholar]; (f) Rieck H, Helmchen G. Angew Chem Int Ed Eng. 1996;34:2687. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogl EM, Buchwald SL. J Org Chem. 2002;67:106. doi: 10.1021/jo010953v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.For early examples of O-alkylation of nitroalkanes see: Wislicenus W, Elvert H. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1908;41:4121.Kohler EP, Stone JF. J Am Chem Soc. 1930;52:761.Nenitzescu CD, Isaăcescu DA. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1930;63:2484.Thurston JT, Shriner RL. J Am Chem Soc. 1935;57:2163.Brown GB, Shriner RL. J Org Chem. 1937;02:376.Weisler L, Helmkamp RW. J Am Chem Soc. 1945;67:1167.

- 5.Hass HB, Bender ML. J Am Chem Soc. 1949;71:1767. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kornblum N. Angew Chem Int Ed Eng. 1975;14:734. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Seebach D, Lehr F. Angew Chem Int Ed Eng. 1976;15:505. [Google Scholar]; (b) Seebach D, Henning R, Lehr F, Gonnermann J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977;18:1161. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Katritzky AR, De Ville G, Patel RC. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1979:602. [Google Scholar]; (b) Katritzky AR, Kashmiri MA, De Ville GZ, Patel RC. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:90. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Russell GA, Hershberger J, Owens K. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:1312. [Google Scholar]; (b) Russell GA, Khanna RK. Tetrahedron. 1985;41:4133. [Google Scholar]; (c) Branchaud BP, Yu GX. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:6545. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Jana R, Pathak TP, Sigman MS. Chem Rev. 2011;111:1417. doi: 10.1021/cr100327p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rudolph A, Lautens M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:2656. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gosmini C, Begouin J-M, Moncomble A. Chem Commun. 2008:3221. doi: 10.1039/b805142a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Pintauer T, Matyjaszewski K. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:1087. doi: 10.1039/b714578k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Clark A. Chem Soc Rev. 2002;31:1. doi: 10.1039/b107811a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Matyjaszewski K, Xia J. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2921. doi: 10.1021/cr940534g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Surry DS, Buchwald SL. Chem Sci. 2010;1:13. doi: 10.1039/C0SC00107D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kizirian JC, Cabello N, Pinchard L, Caille JC, Alexakis A. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:8939. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melzer MM, Mossin S, Dai X, Bartell AM, Kapoor P, Meyer K, Warren TH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:904. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.In all cases, the alkylation reactions are heterogeneous, which we believe is due to the low solubility of the nitronate anions in the apolar media. We believe that the failure of the reactions involving lithium salts stems from the very low solubility of the lithium nitronates.

- 16.Screening reactions were set up inside a nitrogen-filled glovebox. The use of NaOtBu, due to its limited hydroscopicity compared to KOtBu, also allowed the reactions to be performed on the bench, using standard Schlenk techniques. With the exception of 38, all isolated yields refer to reactions run on the bench. All reported isolated yields are the average of at least two independent experiments.

- 17.Lower catalyst loading resulted in lower yields.

- 18.In some cases, particularly those involving more polar substrates, preforming the catalyst in situ, the use of alternative solvents, such as 1,4-dioxane, or weaker bases, such as NaOSiMe3, proved superior to the standard conditions. When substrates contained methyl esters, NaOMe was used as the base.

- 19.(a) Denissova I, Barriault L. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:10105. [Google Scholar]; (b) Riant O, Hannedouche J. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:873. doi: 10.1039/b617746h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nugent TC, editor. Chiral Amine Synthesis: methods, developments and applicaitons; Wiley-VCH Verlag; Weinheim: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.The reaction providing 38 proved very sensitive to oxygen and was performed in a nitrogen-filled glovebox.

- 21.(a) Herman GA, Bergman A, Liu F, Stevens C, Wang AQ, Zeng W, Chen L, Snyder K, Hilliard D, Tanen M, Tanaka W, Meehan AG, Lasseter K, Dilzer S, Blum R, Wagner JA. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46:876. doi: 10.1177/0091270006289850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pauwels RA, Löfdahl CG, Postma DS, Tattersfield AE, O’Byrne P, Barnes PJ, Ullman A. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1405. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711133372001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Armstrong HE, Galka A, Lin LS, Lanza TJ, Jr, Jewell JP, Shah SK, Guthikonda R, Truong Q, Chang LL, Quaker G, Colandrea VJ, Tong X, Wang J, Xu S, Fong TM, Shen C-P, Lao J, Chen J, Shearman LP, Stribling DS, Rosko K, Strack A, Ha S, Van der Ploeg L, Goulet MT, Hagmann WK. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:2184. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.01.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Rubino DM, Gadde KM. J Clin Lipid. 2012;7:13. [Google Scholar]; (b) O’Neil JM, editor. The Merck Index. 14. Merck and Co., Inc; Whitehouse Station. N. J., USA: 2006. p. 1254. [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Shelton RS, Van Campen MG. U.S. Patent, 2408345. 1946; (b) Marquardt FH, Edwards S. J Org Chem. 1972;37:1861. doi: 10.1021/jo00976a057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shetty BV. J Org Chem. 1961;26:3002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.We note that radical chain pathways are also possible; detailed studies are now underway to further define the mechanism.

- 26.(a) Nicewicz DA, MacMillan DWC. Science. 2008;322:77. doi: 10.1126/science.1161976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yoon TP, Ischay MA, Du J. Nat Chem. 2010;2:527. doi: 10.1038/nchem.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Narayanam JMR, Stephenson CRJ. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:102. doi: 10.1039/b913880n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The reactions reported herein do not require light. Control experiments demonstrate that similar yields are obtained when the reactions are run in the dark.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.