Abstract

Summary: We present a Cytoscape plugin called Mosaic to support interactive network annotation, partitioning, layout and coloring based on gene ontology or other relevant annotations.

Availability: Mosaic is distributed for free under the Apache v2.0 open source license and can be downloaded via the Cytoscape plugin manager. A detailed user manual is available on the Mosaic web site (http://nrnb.org/tools/mosaic).

Contact: apico@gladstone.ucsf.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

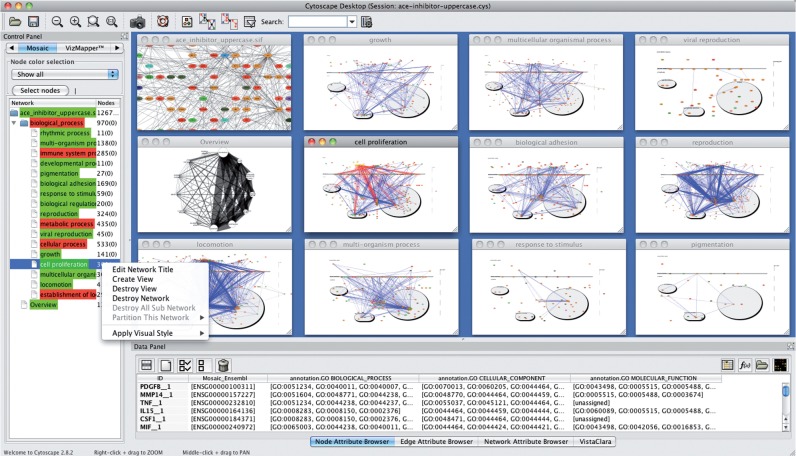

The increasing throughput and quality of molecular measurements in the domains of genomics, proteomics and metabolomics continue to fuel the understanding of biological processes. Collected per molecule, the scope of these data extends to physical, genetic and biochemical interactions that in turn comprise extensive networks. There are software tools available to visualize and analyze data-derived biological networks (Smoot et al., 2011). One challenge faced by these tools is how to make sense of such networks often represented as massive ‘hairballs’. Many network analysis algorithms filter or partition networks based on topological features, optionally weighted by orthogonal node or edge data (Bader and Hogue, 2003; Royer et al., 2008). Another approach is to mathematically model networks and rely on their statistical properties to make associations with other networks, phenotypes and drug effects, sidestepping the issue of making sense of the network itself altogether (Machado et al., 2011). Acknowledging that there is still great value in engaging the minds of researchers in exploratory data analysis at the level of networks (Kelder et al., 2010), we have produced a Cytoscape plugin called Mosaic to support interactive network annotation and visualization that includes partitioning, layout and coloring based on biologically relevant ontologies (Fig. 1). Mosaic shows slices of a given network in the visual language of biological pathways, which are familiar to any biologist and are ideal frameworks for integrating knowledge.

Fig. 1.

Mosaic Control Panel, context menu and tiled result windows. Mosaic highlights the subset of proteins and interactions associated with ‘cell proliferation’, a significant term from an enrichment analysis in the study of atherosclerosis (King et al., 2005)

Cytoscape is a free and open source network visualization platform that actively supports independent plugin development (Smoot et al., 2011). For annotation, Mosaic relies primarily on the full gene ontology (GO) or simplified ‘slim’ versions (http://www.geneontology.org/GO.slims.shtml). The cellular layout of partitioned subnetworks strictly depends on the cellular component branch of GO, but the other two functions, partitioning and coloring, can be driven by any annotation associated with a major gene or protein identifier system.

2 METHODS

2.1 Annotation

Although Mosaic uses practically any annotation, its primary usage relies on GO (for best results, a reduced subset of GO-slim). GO provides a controlled vocabulary of terms describing key characteristics of gene products (i.e., process, location and function). Currently, Mosaic supports seven species and we provide four different varieties of GO annotations for each species, including three ‘slimmed’ ontologies.

The Mosaic package does not contain any data files. All necessary data for each species are stored on the Mosaic web server where it will be periodically updated. Users can download the corresponding data for their species of interest prior to running Mosaic for the first time. Once the data for one species are successfully downloaded to the local machine, Mosaic can be executed for this species in both offline and online modes. Each time a user starts Mosaic with an Internet connection, Mosaic can synchronize local data information with the server automatically. These data are parsed from Ensembl and GO. Ensembl ID is recommended as the unifying identifier for user networks, although several other identifier systems are also supported in Mosaic.

2.2 Partition

The network is partitioned into a set of subnetworks based on the GO Biological Process annotation of the nodes. For example, all nodes annotated with the GO term ‘translation’ are placed in a new subnetwork entitled ‘Translation’. Subnetworks are hierarchically organized to reflect the parent–child relationships between GO terms, and Mosaic only displays those subnetworks with node counts between minimum and maximum thresholds defined in the settings panel. When a given node is annotated with more than one Biological Process term, it is replicated and placed into each corresponding subnetwork.

An overview network is also created, with each node representing a Biological Process subnetwork. Node size reflects the number of genes in the corresponding subnetwork and edge weight represents the number of edges (connections) between the nodes in two subnetworks.

In the Mosaic Control Panel (Fig. 1), all subnetworks are listed hierarchically, including subnetworks that fall outside defined thresholds for display. Selecting a subnetwork in the Control Panel will bring it into focus in the tiled window view. Additional functions can be accessed by right-clicking on the name of a particular subnetwork in the Control Panel. In particular, ‘partition this network to one further level’ allows users to partition a huge network to deep levels of GO efficiently without generating hundreds of other subnetworks from parallel branches.

2.3 Compartmental layout

Mosaic performs cell-based layouts using a cell template that defines graphical regions corresponding to cellular compartments and locations. Nodes are positioned into regions based on their GO cellular component annotation or in an ‘unassigned’ region (right margin) if no annotations are present. Once nodes have been assigned to regions and positioned, a force-directed layout is applied to nodes within each region. Nodes annotated as being located in more than one cellular component are replicated across regions. A suffix is added to the node IDs for replicated nodes, whereas the ‘canonical name’ is retained as the original node ID and used as the node label. In addition, replicate nodes are given a red border.

Because of node replication, relevant edges are also copied. To reduce the complexity of the network, while retaining the original information, edges can be pruned using a deletion strategy to remove certain edges. The strategy is to keep those replicate edges that are completely contained within a region and delete those replicate edges that extend between different regions. The cellular layout algorithm stores region assignment and whether a node exists in multiple regions as node attributes. Information on whether an edge connects to a node annotated as ‘unassigned’ is stored as an edge attribute.

2.4 Visual style

The final step in Mosaic is to apply color to nodes based on their GO Molecular Function annotation. If a node has multiple Molecular Function annotations, the most specific annotation will determine the node color. At the top of the Mosaic Control Panel, sets of nodes can be selected to display detailed information with the ‘Select nodes’ button. By clicking the ‘Legend’ button, the color legend of all Molecular Function terms can be toggled on and off.

3 CONCLUSION

Mosaic provides researchers with an interactive tool to evaluate biological interactions within the context of well-defined processes, functions and cellular localization while retaining all original network information. Use of additional ontologies is anticipated to provide further insights into the relevance of large-scale interaction datasets and will be supported in future versions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Jiguang Wang for discussion, testing and future planning.

Funding: National Institutes of Health [NRNB GM103504 to A.R.P. and R33 GM078601 to D.X.]; Google Summer of Code program [to C.Z.]

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Bader G.D., Hogue C.W. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelder T., et al. Finding the right questions: exploratory pathway analysis to enhance biological discovery in large datasets. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000472. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J.Y., et al. Pathway analysis of coronary atherosclerosis. Physiol. Genomics. 2005;23:103–118. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00101.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado D., et al. Modeling formalisms in systems biology. AMB Express. 2011;1:45. doi: 10.1186/2191-0855-1-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer L., et al. Unraveling protein networks with power graph analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2008;4:e1000108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoot M.E., et al. Cytoscape 2.8: new features for data integration and network visualization. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:431–432. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]