Abstract

Motivation: Conserved patterns across a multiple sequence alignment can be visualized by generating sequence logos. Sequence logos show each column in the alignment as stacks of symbol(s) where the height of a stack is proportional to its informational content, whereas the height of each symbol within the stack is proportional to its frequency in the column. Sequence logos use symbols of either nucleotide or amino acid alphabets. However, certain regulatory signals in messenger RNA (mRNA) act as combinations of codons. Yet no tool is available for visualization of conserved codon patterns.

Results: We present the first application which allows visualization of conserved regions in a multiple sequence alignment in the context of codons. CodonLogo is based on WebLogo3 and uses the same heuristics but treats codons as inseparable units of a 64-letter alphabet. CodonLogo can discriminate patterns of codon conservation from patterns of nucleotide conservation that appear indistinguishable in standard sequence logos.

Availability: The CodonLogo source code and its implementation (in a local version of the Galaxy Browser) are available at http://recode.ucc.ie/CodonLogo and through the Galaxy Tool Shed at http://toolshed.g2.bx.psu.edu/.

Contact: p.baranov@ucc.ie or brave.oval.pan@gmail.com

1 INTRODUCTION

‘Sequence logos’ are simple graphical representations of conserved elements in multiple sequence alignments. Sequence logos were first introduced by Tom Schneider and colleagues (Schneider and Stephens, 1990). However, the popularity of sequence logos was greatly boosted by the advent of WebLogo (Crooks et al., 2004), which provides a web-based interface for sequence logo generation. WebLogo allows the processing of multiple sequence alignments and generates a logo where each column of the alignment is represented by a stack of letters. The height of the entire stack is proportional to its informational content (maximum—2 bits for nucleotides and 4.32 bits for amino acids), whereas the height of each symbol is proportional to its frequency.

Sequence logos inspired development of several other tools that use principles of Shannon's information theory (Shannon, 1948) for graphical visualization of conserved biological elements. For example, RNALogo (Chang et al., 2008) allows visualization of conservation of nucleotides in the context of secondary RNA structures diagrams. CorreLogo (Bindewald et al., 2006) generates 3D images that represent not only local conservation of nucleotides but also mutual information, thus allowing for visualization of double-stranded regions in RNA structures, the characteristic signature of which is compensatory mutations (Dixon and Hillis, 1993). BLogo (Li et al., 2008) allows one to visualize both overrepresented and underrepresented symbols in multiple alignments. Logopaint improves visualization of patterns within alignments of coding regions by removing distortion caused by unequal evolutionary rates for synonymous and non-synonymous substitutions (Schreiber and Brown, 2002). We have been able to identify 13 different tools (data not shown), freely available through the Web that are closely related to the idea behind sequence logos. Despite the impressive fertility of sequence logos, we have not been able to find a single tool that enables visualization of codon patterns.

Codons have specific biological meaning during translation. Codons are the units interacting with transfer RNAs (tRNAs) during protein sequence decoding, and on numerous occasions the meaning of synonymous codons is not the same. Synonymous codon substitutions could have drastic effects on such phenomena as programmed ribosomal frameshifting (Baranov et al., 2002; Namy et al., 2004), and they also could affect speed (Tuller et al., 2010) and accuracy of translation (Drummond and Wilke, 2008). Moreover, altered combinations of codons could greatly affect the overall efficiency of translation (Coleman et al., 2008). Therefore, it is clear that the patterns of codons have biological significance. However, as we show, standard sequence logos are unable to discriminate between conserved patterns of codons and conserved patterns of nucleotides if the nucleotide composition of multiple alignment columns is the same. To overcome the current limitations of sequence logos, we have developed a new tool that we have named CodonLogo.

2 ALGORITHM AND IMPLEMENTATION

CodonLogo is based on WebLogo3. The source code for WebLogo3 (http://WebLogo.threeplusone.com/) has been modified so that the information content is determined across three consecutive columns instead of a single column treating each codon as a member of a 64-symbol alphabet. The information content of a particular codon column in a multiple sequence alignment is determined according to

where pi is the relative frequency of the ith codon in the particular column of the alignment. IC can be adjusted for background compositional bias and small sample correction. Background models can be provided as frequencies of codons and three (for Homo sapiens, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli) are distributed with CodonLogo. The source code of CodonLogo is freely available at http://recode.ucc.ie/CodonLogo. CodonLogo also can be used without the need for local installation through the Galaxy browser interface (Blankenberg et al., 2010; Giardine et al., 2005; Goecks et al., 2010) that is available through the above URL and the Galaxy Tool Shed repository at http://toolshed.g2.bx.psu.edu/. CodonLogo requires the CoreBio and NumPy libraries to run locally.

As input, CodonLogo accepts multiple alignments in a variety of formats (nbrf, fasta, clustal, phylip, genbank, stockholm, msf, nexus and table format). CodonLogo generates output images in either png, eps, pdf or jpeg. While using CodonLogo, users can specify a reading frame for separating nucleotide sequences on codons. It is possible to limit generation of CodonLogo images to a particular subsection of a multiple alignment.

3 PERFORMANCE

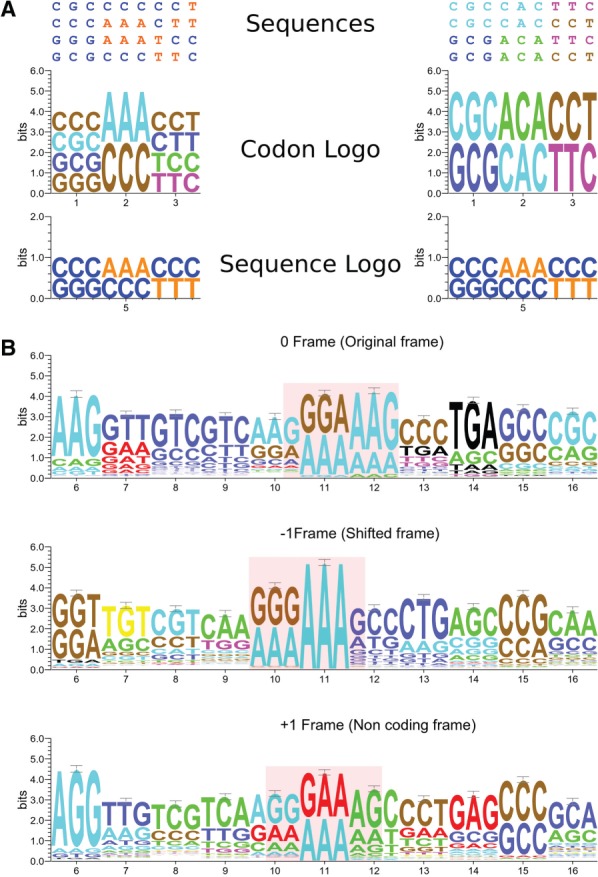

We illustrate the advantages of CodonLogo in comparison to sequence logos in Figure 1. Figure 1A shows an artificial situation, where two alignments are compared. Both alignments have the same nucleotide composition and the same frequency of nucleotides per column. However, in one alignment, codons are conserved (same codons occur in the same column), while in the other alignment codons appear only once in a column. Standard sequence logos are identical for both alignments; however, CodonLogo is able to discriminate between the two situations. Figure 1B illustrates a real example, where the use of CodonLogo is beneficial. In this example, the CodonLogo output was generated for a subsection (857 sequences) of a multiple alignment of insertion sequences from the IS407 family containing a site of programmed ribosomal frameshifting that differs among individual IS elements (Sharma et al., 2011). As it can be seen in Figure 1B, CodonLogo successfully captures conservation of the patterns. We found this program to be useful in visualization of patterns responsible for recoding as those identified in a recent study (Sharma et al., 2011).

Fig. 1.

Performance of CodonLogo. (A) In this example, two different multiple alignments are shown with the same nucleotide composition per column. CodonLogo is capable of distinguishing between two different situations that appear indistinguishable with WebLogo. (B) CodonLogo output for an alignment of 857 insertion sequences from the IS407 family requiring programmed ribosomal frameshifting for their expression (see text). CodonLogo output was produced in three different frames as indicated. The site of programmed ribosomal frameshifting is highlighted

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank LAPTI laboratory members for suggestions during CodonLogo development.

Funding: Wellcome Trust [094423 to P.V.B]

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Footnotes

† The authors wish it to be known that, in their opinion, the first two authors should be regarded as joint first authors.

REFERENCES

- Baranov P.V., et al. Recoding: translational bifurcations in gene expression. Gene. 2002;286:187–201. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00423-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindewald E., et al. CorreLogo: an online server for 3D sequence logos of RNA and DNA alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W405–W411. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenberg D., et al. Galaxy: a web-based genome analysis tool for experimentalists. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1910s89. Chapter 19, Unit 19.10.1–19.10.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T.H., et al. RNALogo: a new approach to display structural RNA alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W91–W96. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J.R., et al. Virus attenuation by genome-scale changes in codon pair bias. Science. 2008;320:1784–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.1155761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks G.E., et al. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon M.T., Hillis D.M. Ribosomal RNA secondary structure: compensatory mutations and implications for phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1993;10:256–267. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a039998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond D.A., Wilke C.O. Mistranslation-induced protein misfolding as a dominant constraint on coding-sequence evolution. Cell. 2008;134:341–352. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardine B., et al. Galaxy: a platform for interactive large-scale genome analysis. Genome Res. 2005;15:1451–1455. doi: 10.1101/gr.4086505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goecks J., et al. Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R86. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., et al. BLogo: a tool for visualization of bias in biological sequences. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2254–2255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namy O., et al. Reprogrammed genetic decoding in cellular gene expression. Mol. Cell. 2004;13:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T.D., Stephens R.M. Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6097–6100. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber M., Brown C. Compensation for nucleotide bias in a genome by representation as a discrete channel with noise. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:507–512. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.4.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst Tech J. 1948;27:379–423. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V., et al. A Pilot study of bacterial genes with disrupted ORFs reveals a surprising profusion of protein sequence recoding mediated by ribosomal frameshifting and transcriptional realignment. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28:3195–3211. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuller T., et al. An evolutionarily conserved mechanism for controlling the efficiency of protein translation. Cell. 2010;141:344–354. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]