Over the last 40 years, financial pressures and incentives have reshaped health care delivery in the United States. One important recent change is the implementation of measures to quantify and incentivize physician work.1–3 Although implementation of productivity targets has been shown to increase physician work, the impact of these changes on the academic missions of teaching, research and patient care has not been adequately studied.

Methods

We surveyed physicians in the department of medicine at a large academic medical center to determine the impact of recently implemented work targets on attitudes and behaviors toward teaching, research and clinical care (response rate 64%, n=137). Responders were asked 29 questions about the impact of work targets on their performance of various academic activities in the years before and after introduction of this policy. Data were analyzed using STATA statistical software and the Prism software. Student’s t-test was used for data that were normally distributed and Wilcoxon Rank Sum was used for data not distributed normally. We compared proportions between groups using Chi-square tests.

Results

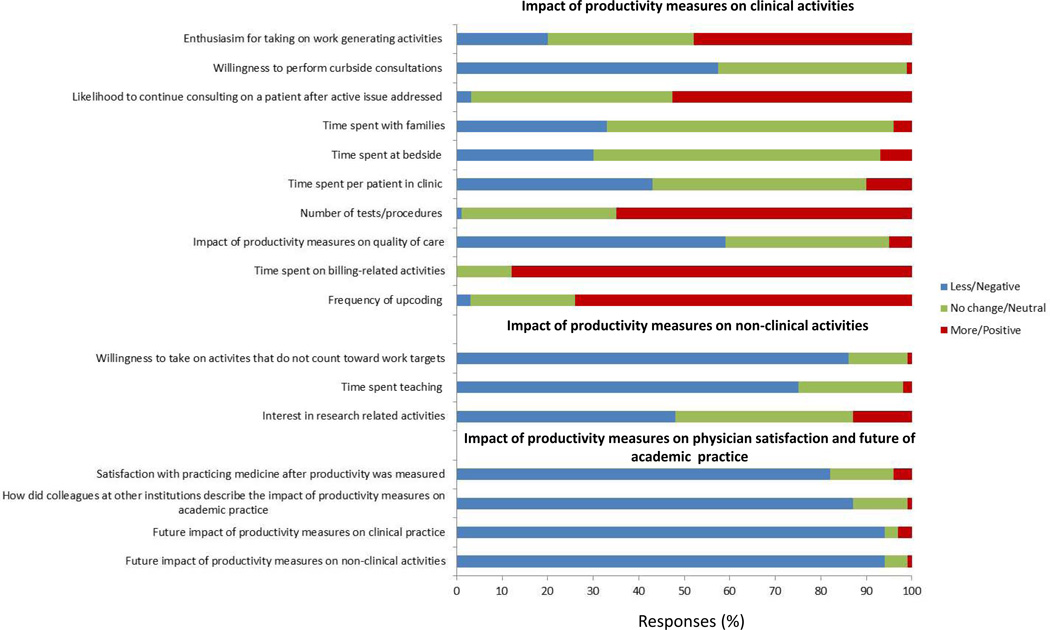

Nearly half (47%) of physicians described themselves as being more inclined to take on clinical activities after work targets were measured (Figure). However, increased focus on clinical duties was associated with changes in the ways physicians carried out these activities. Physicians reported being less willing to perform curbside consultations, and more likely to continue consulting on a patient after the initial active issue was addressed. 43% perceived that time spent per patient in clinic decreased; this effect was much more pronounced among physicians providing primarily E&M visits rather than procedures (50% vs. 17%, p=0.03). Over half felt that quality of care declined, the number of tests/procedures increased and patients were worse off after work was measured. Physicians in procedure-based specialties (gastroenterology, pulmonary and cardiology) reported they were more likely to perform a procedure for which there was only a marginal indication (23.2% after vs. 15.6% before, p<0.05).

Figure.

Physician perception of the impact of productivity measures on clinical and non-clinical activities

The impact of work targets on non-clinical activities was unfavorable. 86% of physicians reported being less inclined to perform activities that did not count toward work targets. Some 75% of physicians reported a decrease in time spent teaching. Almost half (48%) of physicians reported a decrease in interest in research-related activities, and this was particularly true for physicians who derived more than half of their salary from clinical activities (61% vs. 34%, p=0.01).

Lastly, satisfaction with practicing academic medicine decreased after implementing work targets. 89% of physicians said they had been satisfied with practicing medicine in the years before work was measured but only 16% described themselves as satisfied after productivity was measured. Many respondents wrote in comments about the model’s harm to physician morale, collegiality, and job satisfaction. Importantly, these findings do not appear specific to this institution since many respondents stated that colleagues at other institutions, who work in a similar system, have mentioned a negative impact of work targets on their practice. Finally, 94% of physicians were pessimistic about the future of academic medicine under a work-productivity model.

Comments

This study shows that measuring physician work has intended and unintended consequences. While our results confirm previous reports that physicians are more inclined to perform clinical duties,4–6 we also found changes in the ways physicians performed their clinical duties—including some behaviors that boosted measured productivity (decreased curbside consultations, increased up-coding) and others possibly not in patients’ best interests (e.g., more tests and procedures).

It is troubling that physicians providing primarily E&M visits were much more likely to report drops in physician time per encounter than were physicians performing procedures. This may signal that the productivity metric employed at this medical center has the effect of perpetuating the often-criticized under-valuation of physicians’ cognitive services found in both UCR and RBRVS fee schedules.7

Another important finding of this study was the unfavorable impact of productivity measures on teaching and research. 86% of physicians admitted being less inclined to perform activities that did not count toward productivity targets. Physicians made it very clear that they were less willing to teach. This was evident from both direct questioning and written comments. Of 86 physicians providing commentary, 35% mentioned a concern over the impact on medical education. If our findings hold true, medical schools and training programs should begin to monitor trainees to ensure that quality of education is not being harmed.

Satisfaction with practicing medicine decreased dramatically after work was measured. Although we are unable to determine why physicians were so dissatisfied, we suspect it relates to the way productivity is monitored and enforced; perceived concerns over effects of increased clinical productivity on quality of care, teaching and research; and other factors.

This study is limited. It is a single-center study so findings may not be applicable to other academic medical centers. It was restricted to the department of medicine, so findings may not apply to physicians in other specialties. The response rate was 64%. While an excellent response rate for a non-incentivized physician survey, it is possible that those most affected were more likely to reply and higher response rates might yield different results.

In conclusion, results indicate that setting work targets does not simply increase clinical productivity. Doing so has many unintended consequences that affect all three missions of academic medical centers. As one physician respondent put it, “while the RVU system undoubtedly increases productivity, it is an anti-intellectual exercise that is anathema to the academic mission.” We believe it would be wise for leaders of academic institutions to closely monitor the impact of work targets on the performance of physicians’ vital clinical and non-clinical tasks.

Footnotes

Author contributions for this manuscript included: Study concept and design: Summer, Wiener and Sager. Acquisition of data: Summer and Carroll. Analysis and interpretation of data: Summer, Wiener and Sager. Drafting of the manuscript: Summer and Sager. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Summer, Wiener, Carroll, Sager. Statistical analysis: Summer and Wiener. Administrative and technical support: Summer and Carroll. Study supervision: Summer

References

- 1.Andreae MC, Freed GL. The rationale for productivity-based physician compensation at academic health centers. The Journal of pediatrics. 2003 Dec;143(6):695–696. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsiao WC. The resource-based relative value scale: an option for physician payment. Inquiry : a journal of medical care organization, provision and financing. 1987 Winter;24(4):360–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsiao WC, Braun P, Dunn D, Becker ER, DeNicola M, Ketcham TR. Results and policy implications of the resource-based relative-value study. The New England journal of medicine. 1988 Sep 29;319(13):881–888. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809293191330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andreae MC, Blad K, Cabana MD. Physician compensation programs in academic medical centers. Health care management review. 2006 Jul-Sep;31(3):251–258. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200607000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andreae MC, Freed GL. Using a productivity-based physician compensation program at an academic health center: a case study. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2002 Sep;77(9):894–899. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200209000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arenson RL, Lu Y, Elliott SC, Jovais C, Avrin DE. Measuring the academic radiologist's clinical productivity: survey results for subspecialty sections. Academic radiology. 2001 Jun;8(6):524–532. doi: 10.1016/S1076-6332(03)80627-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandy LG, Bodenheimer T, Pawlson LG, Starfield B. The political economy of U.S. primary care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009 Jul-Aug;28(4):1136–1145. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]