Abstract

Homeless shelters provide a unique opportunity to intervene with occupants who have substance abuse problems, as not addressing these issues may lead to continuation of problems playing a contributing role in homelessness. Attempts to implement Contingency Management (CM) with this population have often been complex, costly, and not straightforward to replicate in community settings. We conducted a randomized trial evaluating a simple, low-cost 4-week CM program for 30 individuals seeking shelter in a community-based homeless shelter who had both current substance and psychiatric disorders. Behavioral assessments were performed at baseline, weekly, and termination of the study. Overall retention in the trial was high; participants assigned to CM reduced their cocaine and alcohol use more than those in assessment-only. This pilot trial suggests that application of low-cost CM procedures is feasible within this novel setting and may decrease substance use.

Keywords: Alcohol use disorders, cocaine use disorders, contingency management, homelessness, psychiatric disorders

Behavioral treatments based on contingency management have shown robust effects in improving the efficacy of drug abuse treatment (1–3). Given the success of CM procedures, investigators have applied these techniques to reduce substance use in individuals who are homeless and have had difficulty engaging and benefiting from traditional substance abuse treatment. Existing CM approaches for homeless populations such as creating contingent housing or the opportunity for work based on abstinence have been demonstrated to be effective in controlled trials (4, 5), but may be both too costly and complex to deliver within the context of an already established community facility.

An alternative could be to explore the use of lower cost less intrusive reinforcers in reducing substance use and retention in homeless populations. One approach of this nature is a low-cost contingency management program which utilizes drawings for prizes as reinforcement (6). We conducted a randomized controlled pilot study to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of using low-cost contingency management to enhance retention and reduce substance use among dually diagnosed homeless individuals in a relatively research naïve setting.

METHOD

Participants/Screening

Participants were 30 individuals seeking shelter at Columbus House, a community-based homeless shelter in New Haven, Connecticut. Participants were eligible for the study if they (1) met current or lifetime DSM-IV diagnosis of an Axis I psychiatric disorder, (2) had a co-occurring current diagnosis of cocaine or alcohol abuse or dependence, (3) were seeking shelter, and (4) were at least 18 years of age. After written informed consent was obtained, screening for diagnoses occurred through administration of the Structural Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I/P) (7) and the baseline assessment battery was completed on those eligible as described below in the assessment section.

Treatment Conditions

Eligible participants were randomized using a randomization table to Contingency Management (CM) or assessment-only treatment condition for 4 weeks. Participants in both conditions had access to all shelter services for the duration of the study. Those assigned to the assessment-only condition received assessments at baseline, weekly during treatment, and at the post treatment assessment. Those in the CM condition had similar assessments performed plus they received the intervention.

The CM intervention was Petry’s (6) low-cost contingency management with variable-ratio reinforcement, where participants received reinforcers contingent upon demonstrating abstinence from both alcohol and cocaine, as verified by cocaine-free urine specimens and breathalyzer specimens collected twice weekly and for attendance.

Each individual who demonstrated abstinence and/or attendance was given a number of chances to draw from the prize bowl for prizes immediately after the results of the sample were provided. The number of chances was relative to the behavior demonstrated and escalated in schedule. If the individual provided a positive urine or breathalyzer sample at any time or did not provide a scheduled sample, the rate of reinforcement returned to week 1 level until the individual provided 2 consecutive negative urine and breathalyzer samples where he/she was able to resume to his or her previous rate prior to relapse.

The prize bowl contained 250 slips of paper with redeemable prizes on them (e.g., candies, hygiene products, shelter vouchers, compact disc player, clothing items). Prizes ranged in value and approximate probability from no redeemable prize (1 in 2 chance of receiving), $1 (slightly less than 1 in 2 chance of winning), $20 (1 in 25 chance of winning), and $100 (1 in 250 chance of winning). If participants attended all sessions and all urine and breath specimens were negative, a total maximum of 48 prize draws was available with a maximum expected value of $81.60 in prizes.

Assessments

The first primary outcome variable was self-reported cocaine use, as assessed by the Substance Use Calendar (SUC) which is similar to the time line follow back and provides a detailed day to day report of substance use (8). The SUC was administered baseline and weekly and verified by urine samples collected baseline and twice weekly from participants in both conditions. Due to excellent agreement between the SUC and urine sample data [only 4%(8/203) disagreement], we chose to use the SUC data where either a positive sample or a self-report was coded as positive to achieve the most accurate assessment of use.

The second primary outcome variable was alcohol use, as assessed by breathalyzer samples collected baseline and twice weekly. We also conducted analyses with the alcohol SUC data compared to breathalyzer data and found similar agreement [only 4.7% (11/235) disagreement]. Again, we utilized the most conservative index and coded persons as positive if either a positive sample or a self-report was noted.

The Addiction Severity Index (ASI) was administered baseline and post treatment to further assess substance use (9). Individuals in both conditions received compensation for assessments as follows: $30 for screening, baseline, and termination interviews and $5 for each weekly assessment.

RESULTS

Sample Description

Forty-six individuals were screened for the study; 30 were determined to meet eligibility criteria and were randomized with 15 participants in each condition. Of those who were randomized, 86.6% (26) completed the post treatment assessment and 13.3% (4) did not complete the study. All participants who did not complete the study were in the assessment-only condition.

On most common demographic and homeless variables, there were no differences between the CM intervention and assessment-only with exception of a greater number of women being assigned to assessment only compared to CM (80% vs. 20%) (N = 30), X2(1) = 5.00, p = .02.

There were no significant differences between the CM and the assessment-only condition on psychiatric disorder diagnoses, substance disorder diagnoses, average years use, and number of days pretreatment use for all substances with the exception of cocaine. The CM intervention participants were more chronic cocaine users with more than double the number of years cocaine use (N = 30); mean of 17.73 years (SD = 13.02) versus 8.60 (SD = 7.38); F(1, 28) = 5.59, p = .02 and had a greater baseline frequency of cocaine use (N = 30); mean of 7.33 days of cocaine use (SD = 5.73) versus 2.60 (SD = 3.11); F(1, 28) = 7.91, p = .009. As a result, ANOVA and random effect regression model analyses were conducted co-varying for frequency of cocaine use.

Prizes Earned

There were 622 total draws for all CM participants (277 = no prize, 329 = $1 prize, 16 = $20 prize, and 0 = $100 prize) with the average participant having 41.46 draws. The average amount earned was $43.27 with the minimum earned being $22 and the maximum being $91.

Substance Use Outcomes by Treatment Condition

Substance use during the trial was low overall; participants averaged 85% days with no cocaine use (CM = 96%, assessment-only = 75%) with similar percentages for days no alcohol use.

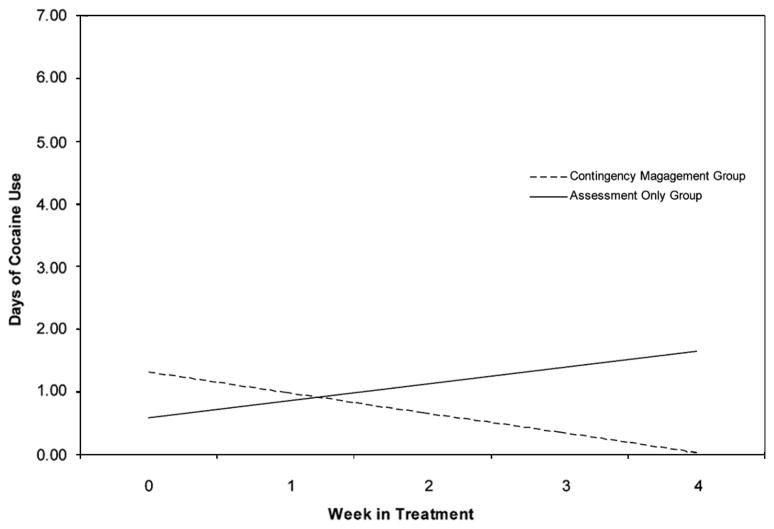

The CM participants reported significantly fewer days of cocaine use than participants in the assessment-only (N = 30), F(1, 27) = 5.67, p = .02. As shown in Figure 1, random effect regression model analysis indicated significant effects for the CM by time contrast, Z = 2.43, p = .02, suggesting participants assigned to the CM intervention made greater reduction in their frequency of cocaine use overtime compared to those in the assessment-only.

Figure 1.

Random effect regression model of days of cocaine use by week by treatment condition.

The participants assigned to CM also reported significantly fewer days of alcohol use than participants in assessment-only (N = 30), F(1, 27) = 6.83, p = .01. Moreover, participants in the CM had significantly fewer alcohol positive breathalyzer samples (N = 30), X2(1) = 14.75, p = .000.

DISCUSSION

We conducted a randomized trial evaluating a simple, low-cost contingency management program for individuals in a community based homeless shelter who had both current substance and psychiatric disorders. Overall retention in the trial was high with 100% retention in the CM condition. Participants assigned to the CM intervention reported less alcohol use both by self report and biological markers and reduced their cocaine use more than those in assessment-only.

This trial demonstrates the feasibility and potential efficacy of this CM intervention in a novel community setting. Homeless shelters meet emergent immediate needs of individuals who are vulnerable and often dealing with multiple stressors including substance abuse. As a result, shelters provide a unique opportunity to introduce occupants to therapeutic treatment as a means to avoid a revolving door experience of getting crisis housing needs met, but not addressing contributing factors that may lead to housing instability.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by NIDA grants P50-DA0924, K05-DA00457, KO5-DA00089, and U10-DA13046. We are grateful to the participants and staff at Columbus House for their support of this project and the staff at the NIDA Yale Psychotherapy Development Center for their contributions to this project.

References

- 1.Higgins ST, Alessi SM, Dantona RL. Voucher-based incentives. A substance abuse treatment innovation. Addict Behav. 2002;27(6):887–910. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petry NM, Martin B. Low-cost contingency management for treating cocaine and opioid abusing methadone patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:398–405. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverman K, Wong CJ, Umbricht-Schneiter A, Montoya ID, Schuster CR, Preston KL. Broad beneficial effects of cocaine abstinence reinforcement among methadone patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:811–824. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.5.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milby JB, Schumacher JE, Raczynski JM, Caldwell E, Engle M, Michael M, Carr J. Sufficient conditions for effective treatment of substance abusing homeless persons. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;43:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milby JB, Schumacher JE, McNamara C, Wallace D, Usdan S, McGill T, Michael M. Initiating abstinence in cocaine abusing dually diagnosed homeless persons. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;60:55–67. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petry NM, Martin B, Cooney JL, Kranzler HR. Give them prizes, and they will come: Contingency management for treatment of alcohol dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:250–257. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbons M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1995. Patient Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, Rutigliano P. The timeline followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:134–144. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLellan TA, Luborsky L, Cacciola JS, Griffith JE. New data from the Addiction Severity Index: Reliability and validity in three centers. J Nervous Mental Disease. 1985;163:412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]