Abstract

A small but important proportion of patients with myasthenia gravis (MG) are refractory to conventional immunotherapy. We have treated 12 such patients by “rebooting” the immune system with high-dose cyclophosphamide (Hi Cy, 200 mg/kg), which largely eliminates the mature immune system, while leaving hematopoietic precursors intact. The objective of this report is to describe the clinical and immunologic results of Hi Cy treatment of refractory MG. We have followed 12 patients clinically for 1–9 years, and have analyzed their humoral and cellular immunologic parameters. Hi Cy is safe and effective. All but one of the patients experienced dramatic clinical improvement for variable periods from 5 months to 7.5 years, lasting for more than 1 year in seven of the patients. Two patients are still in treatment-free remission at 5.5 and 7.5 years, and five have achieved responsiveness to immunosuppressive agents that were previously ineffective. Hi Cy typically reduced, but did not completely eliminate, antibodies to the autoantigen AChR or to tetanus or diphtheria toxin; re-immunization with tetanus or diphtheria toxoid increased the antibody levels. Despite prior thymectomy, T cell receptor excision circles, generally considered to reflect thymic emigrant T cells, were produced by all patients. Hi Cy treatment results in effective, but often not permanent, remission in most refractory myasthenic patients, suggesting that the immune system is in fact “rebooted,” but not “reformatted.” We therefore recommend that treatment of refractory MG with Hi Cy be followed with maintenance immunotherapy.

Keywords: myasthenia gravis, refractory MG, high-dose cyclophosphamide, Hi Cy, rebooting the immune system, TRECs, autoimmunity, immunotherapy

Introduction

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is undoubtedly the best understood human autoimmune disease, and is generally the most treatable neuromuscular disorder.1,2 The pathogenesis of MG involves an antibody-mediated autoimmune attack directed against acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) at neuromuscular junctions,3 or in 8–10% of cases, directed against a neighboring protein—muscle-specific tyrosine, kinase (MuSK).4–6 At present, with optimal treatment, the mortality rate is virtually zero, and the great majority of myasthenic patients can be returned to full productive lives.7 Nevertheless, a small but important proportion of myasthenic patients are refractory to conventional therapeutic modalities. Patients are considered “refractory” if they: (a) fail to respond to otherwise adequate doses and durations of conventional immunosuppressive treatments; (b) have unacceptable adverse side effects of the treatments; (c) require excessive amounts of potentially harmful agents; (d) have comorbidities that preclude the use of conventional therapy; or (e) require repeated rescue with short-term intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) or plasma exchange treatments.

We have developed and evaluated a treatment strategy based on the administration of high-dose cyclophosphamide (Hi Cy) that we have termed “Rebooting the Immune System.”8 Ideally, the goal of this treatment is to eliminate the autoimmune response and provide long-term or permanent benefit. Our preclinical studies of Hi Cy treatment of rats with experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis (EAMG) utilized “rescue” by transplantation of syngeneic bone marrow (see Discussion). More recent experience with Hi Cy in human autoimmune hematologic disorders, such as aplastic anemia, hemolytic anemia, and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, revealed that bone marrow transplantation is not essential to restore the immune/hematologic system after Hi Cy treatment.9–12 Hematopoietic stem cells are not damaged by cyclophosphamide, because they express high levels of aldehyde dehydrogenase, which inactivates the active metabolite of cyclophosphamide. In contrast, lymphocytes and committed hematopoietic progenitors are rapidly destroyed by cyclophosphamide because they express only low levels of aldehyde dehydrogenase.13–15 After Hi Cy treatment, the undamaged hematopoietic precursor cells proliferate, enhanced and accelerated by administration of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), and reconstitute the immune system. Five years ago we published our initial results in three patients.8 The current report includes our findings in 12 patients followed from 12 months to 9 years. Our results show that all of the patients tolerated the treatment well. All but one showed clinically obvious improvement that has lasted variably from 5 months to more than 7 years, and may be durable in some, but not all, patients.

Subjects and Treatment (Table 1a and b)

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patients #1–6 (a) and #7–12 (b) before, during, and after Hi Cy treatment

| (a) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient # | #1 | #2 | #3 | #4 | #5 | #6 |

| Age/gender | 32 F | 36 F | 53 M | 27 F | 24 F | 32 F |

| Duration of MG before Hi Cy | 15 yrs | 3 yrs | 13 yrs | 7 yrs | 5 yrs | 2 yrs |

| MG score Maximum severity Pre Hi Cy | V | IVb | IVb | IVb | IVa | IVb |

| Major Features, Karnovsky scale (at time of Hi Cy) | Bulbar, limb, resp., EOM K = 70 | Bulbar and resp BiPap; K = 40 | Profound bulbar, speech, ocular K = 70 | Ocular, bulbar, limb K = 80 | Ocular, bulbar, limb K = 80 | Resp., ocular, bulbar, limb K = 40 |

| Best MG Score & Karnovsky post Hi Cy | IIa | I | IIb | 0 | IIa | IVb |

| K = 90 | K = 100 | K = 95 | K = 100 | K = 90 | K = 50 | |

| Duration of Improvement | 6 1/2 yrs: Graves’, MG relapse | >7 yrs current | 1 yr; relapse; response to Rx | >5 ½ yrs current | 4 yrs, with immunosupp. | 0 |

| Additional Features Before Hi Cy | A-V fistula for plasmapheresis | SLE; Lupus anti-coag; Thyroiditis; Seizures | Graves’ | Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis; IV Cath. infections | ||

| Treatments Pre-Hi Cy: | ||||||

| Pyridostigmine | 90 mg q 4 h | 120mg tid,TS | 90 mg qid | 60 mg tid | 60 mg qid,TS | 60 qid & TS |

| Steroids | 60 mg/d | 60 mg/d | 15/10 mg | 50/20 mg | 25/5 mg | 70 mg/d |

| Azathioprine | 225 mg/d | 100 mg bid | 325 mg/d | |||

| Cyclosporine | 100 mg/d | FK506 5 bid | 150 mg bid | 150/175 mg/d | ||

| Mycophenolate | 16 courses | 1 gm bid | 1.5 gm bid | 1 gm bid | 1.5 gm bid | |

| IVIg | Many | 15 courses | 1 course | Many | Many | Many |

| Plasmapheresis | q 35 d | Many | 1 course | Many | ||

| Thymectomy | 14 yrs | 2 yrs | 12 yrs | 6 yrs | 3½yr & 1 yr | 1 yr |

| Hospitalizations | Many | 12 in 27 mos | Many | Many | ||

| AChR Antibody: Before/After Hi Cy | 21.1 nM/2.4 | 1.54 nM/0.66 | + MuSK Ab | Ab Negative | 48.24 nM/13.8 | 1.78 nM/0 |

| (b) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient # | #7 | #8 | #9 | #10 | #11 | #12 |

| Age/gender | 43 M | 40 F | 47 F | 67 M | 40 F | 43 F |

| Duration of MG (yrs) | 2 yrs | 5 yrs | 7 yrs | 10 yrs | 7 yrs | 5 yrs |

| MG severity (Maximum) | V | V | V | V | IVb | III |

| Major Features, Karnovsky scale (at time of Hi Cy) | Bulbar, resp., limb K = 60 | Ocular, Bulbar, resp., limb K = 40 | Resp., Dysarthria, Generalized, Dysphagia K = 80 | Ocular, Bulbar Generalized Resp., Dysphagia, Dysarthria K = 70 | Ocular, Bulbar, Generalized Resp. K = 55 | Ocular, Bulbar, Generalized K = 80 |

| Best MG Score & Karnovsky post Hi Cy | IIa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| K = 90 | K = 100 | K = 100 | K = 100 | K = 85 | K = 90 | |

| Duration of Improvement | 3 ½ yrs; Response to immunosupp. | 3 yrs; relapse; Re-treated with Hi Cy; K = 100 | 4 ½ mos., Response to immunosupp. | Relapse after 17 mos. Awaiting re-treatment | Relapse after 5 mos. Good response to immunosupp. | >1 yr, current Graves’ ulcerative colitis |

| Additional Features | Crohn’s H. Zoster Avascular necrosis | Hypertension, Seizures, Tachycardia, Cataracts | Diabetes, Asthma | Coronary bypass; diabetes; Asthma; glaucoma | Premature Ovar. Failure; Hepatitis B; Autoimmune Family History | Ulcerative colitis; Hashimoto’s, Graves’ |

| Treatments: | ||||||

| Pyridostigmine | 90 qid + TS | 60–120 q 3 h | 60 mg 5/d | 60 mg 5/d | 60 mg q 4 h | |

| Steroids | 80/d | 100/d | 80/d | 20/d | 20/d | 60/day |

| Azathioprine | 150/d | 100/d | Intolerant | Intolerant | ||

| Cyclosporine | 125/150 mg/d | 100 mg bid | Intolerant | 200 mg bid | 125 mg bid | |

| Mycophenolate | 1.5 gm bid | 1.5 gm/d | 1 gm bid | |||

| IVIg | 2 courses | q 4 wks | q 4 wks | q month | ||

| Plasmapheresis | Frequent | Many | q 2 wks | |||

| Thymectomy | 1 yr | 1 yr | 6½ yrs | 7 yrs | 6 yrs | 2 yrs |

| Hospitalizations | 2 | Many | Many | Many | Many | |

| AChR Antibody: Before/After Hi Cy | Ab Neg | 1.06 nM/0 | 0.49 nM/0 | 28.9 nM/14.3 | 20.0 nM/6.3 | Ab Neg |

The shaded sections indicate the clinical features immediately before Hi Cy treatment, and after Hi Cy treatment. All patients but #6 showed marked objective improvement.

Each of the12 subjects in this study had a definite clinical diagnosis of MG, with typical physical findings, response to anticholinesterase agents, and at least some improvement with immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory agents. All but one of the patients had antibodies to AChR or MuSK and/or electrophysiologic evidence of MG. All patients who entered this study were selected because their MG was either refractory to multiple immunosuppressive agents or required toxic levels of these agents. There were nine female and three male subjects, ranging in age from 24 to 67 at the time of treatment. At their worst, prior to Hi Cy treatment, five patients were rated grade V (required respiratory assistance), six patients were rated grade IV (severe weakness affecting other than ocular muscles), and one was grade III (moderate weakness affecting other than ocular muscles), according to the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America scale.16 Seven of the patients had additional autoimmune diseases, including five with Hashimoto’s or Graves’ disease prior to or after Hi Cy treatment; one with lupus erythematosus and one with elevated antinuclear antibodies; one with ulcerative colitis; one with Crohn’s disease; and two with asthma. All patients previously had surgical thymectomy performed as part of their MG treatment.

Subjects gave informed consent for the IRB-approved protocol. Examination and baseline testing were performed prior to acceptance for treatment. Exclusion criteria included: cardiac ejection fraction <45%; serum creatinine >2.0; serum bilirubin >2.0 or transaminases >2x normal; forced vital capacity <50% or FEV1 <50% of predicted; evidence of malignancy; Karnofsky17 performance status <40; risk of pregnancy.

The patients were hospitalized for approximately 5 days during the cyclophosphamide treatment. They were initially hydrated, and then cyclophosphamide (50 mg/kg of ideal body weight) was administered over 1 h through a Hickman catheter daily for 4 days (total = 200 mg/kg). Nausea was treated prophylactically with intravenous ondansetron. Intravenous mesna (10 mg/kg) was administered 30 min before, and 3, 6, and 8 h after cyclophosphamide, to prevent hemorrhagic cystitis.

Following the hospitalization, all patients were followed daily with blood counts and physical examination in the specialized outpatient transplant clinic of the Johns Hopkins Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center. Packed red blood cells were given as needed to maintain a hematocrit >25%. Platelet transfusions were administered to maintain platelet counts >10,000/mm3. Beginning on day 6 after the last dose of cyclophosphamide, G-CSF (5 μg/kg) was administered daily until the neutrophil count was ≥1000/mm3 for 2 consecutive days. Prophylactic antibiotics were given beginning 1 day after the last dose of cyclophosphamide and continuing until the neutrophil count exceeded 500 cells/mm3. Prophylaxis against Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia with sulfamethoxazole (800 mg) and trimethoprim (160 mg) was given on 2 days a week for 6 months.

After treatment, patients were followed at 2-monthly intervals for 12 months, and 3-monthly intervals thereafter. They were re-immunized against diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus toxins, and poliomyelitis. Clinical follow-up included general physical examination, spirometry, timed arm abduction, evaluation of extraocular muscles and face, and quantitative dynamometry of nine pairs of limb muscles. Laboratory tests included measurement of AChR antibodies by radioimmunoassay (average of two separate determinations); complete blood counts; lymphocyte subsets CD 3, 4, 8, 19, and 20; measurement of tetanus and diphtheria antibodies by a commercial ELISA method (IVD Research, Carlsbad, CA); and measurement of T cell receptor excision circles (TRECs), by methods similar to those previously described18: for TREC analysis, genomic DNA was extracted using a DNEasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. TREC values were measured using an SYBR green dye based real-time PCR assay, with a Bio-Rad ICycler real-time PCR instrument (Hercules, CA). Primers for TRECs, based on previously published primers were: AGGCTGATCTTGTCTGACATTTGCTCCG and AAAGAGGGCAGCCCTCTCCAAAAA. Primers for the control gene chemokine receptor5 (CCR5) were: CTGTGTTTGCGTCTCTCCCAGG and CACAGCCCTGTCCCTCTTCTTC. Each reaction was run in triplicate, and melting curves were performed to ensure that only a single product was amplified. As an internal control, CCR5 was used to measure cell equivalents in the input DNA. In each genomic DNA sample, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were quantified as 1 cell per 2 CCR5 copies, and TREC values were calculated as the number of TRECs per 106 PBMCs.

Results (Table 1a and b)

Clinical Results

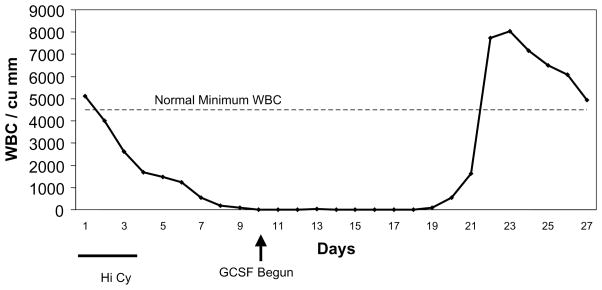

All patients tolerated the Hi Cy infusions well. During the immediate post-treatment period, seven patients were readmitted briefly for antibiotic treatment of neutropenic fever, and all recovered rapidly. The fever was attributable to infections in four of the patients (diverticulitis, axilla abscess, line infection, mycoplasma pneumonitis), while no source of infection was discovered in the other three patients. In all cases, the white blood count (WBC) rose promptly, within 9–18 days after the last dose of cyclophosphamide (3–12 days after beginning G-CSF injections) (Fig. 1). The median number of hospitalized days for these patients was 5 (range 3–21 days). The median number of red blood cell transfusions was two (range 0–6), and the median number of platelet transfusions was two (range 1–5).

FIGURE 1.

Typical leukocyte response in patient #8 after Hi Cy treatment, followed by G-CSF administration. Note the rapid fall after Hi Cy, and quick recovery following G-CSF.

All but one of the patients showed clinically obvious beneficial effects of variable duration. Improvement began within 3 weeks to 3 months. More than half the patients experienced prolonged—possibly permanent—improvement; more than one-quarter became responsive to immunosuppressive agents that were previously ineffective; two patients had short-lived, but dramatic, benefit; and one patient showed no improvement.

Six patients had very good to excellent responses for at least 1 year (#1, 2, 3, 4, 8, and 10). Two of these patients (#2 and #4) have remained in complete remission for 7.5 and 5.5 years, respectively. One patient (#1) had only minimal signs for more than 6 years, and then developed Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, followed by Graves’ disease with thyroid ophthalmopathy, and exacerbation of MG. One patient (#8) remained in completely treatment-free remission for 3 years, but then developed an exacerbation of MG, and was successfully retreated with Hi Cy (see below). Another patient (#10) remained in drug-free remission for 17 months and has just developed an exacerbation; he is scheduled for retreatment with Hi Cy.

One MuSK antibody–positive patient (#3) had a very good response for 1 year and then declined, but acquired responsiveness to immunosuppressive treatment although he had previously been poorly responsive.

Three patients (#3, #5, and #7) improved by acquiring responsiveness to immunosuppressive agents, which had previously been ineffective.

Two patients (#9 and #11) with initially very severe MG responded dramatically for 5 and 7 months, respectively, following Hi Cy, but then developed rapid exacerbations requiring resumption of substantial immunotherapy.

Only one patient (#6) failed to improve after Hi Cy, and has proved resistant to all immunomodulatory treatments subsequently tested with the exception of marginal benefit from IVIg.

Retreatment

Patient #8, who responded dramatically for 3 years prior to exacerbation, has been retreated, and recovered within 2 months to her best level before the exacerbation (Karnofsky status = 100; MG score = 0).

Additional Studies

Autoantibodies—AChR and MuSK

Eight of the patients were initially AChR antibody–positive, and one was MuSK antibody–positive. Following Hi Cy treatment, AChR antibody levels fell in all eight (Table 2). They remained readily detectable in five of the patients, and reached zero only in three patients who had initially low positive titers. In six of the patients, the AChR antibody levels subsequently rose. In four of these patients (#8, 9, 10, and 11), the AChR antibody rise was related to a clinical exacerbation of MG (Fig. 2), while one other (#2) remained in remission although the AChR antibody level showed a moderate rise. One patient (#5) who had responded to immunosuppressive agents only after Hi Cy treatment, stopped her medications and had a significant rise in AChR antibodies as well as an increase in weakness. The one MuSK-positive patient (#3) showed a fall of the MuSK antibody to about 50% at 6 months and a rise to pretreatment levels concomitant with clinical exacerbation at 1 year (kindly measured by Dr. A. Vincent). Thus, Hi Cy treatment lowered the autoantibody levels, but the levels in some patients subsequently rose, either with or without clinical exacerbation.

TABLE 2.

Change in AChR antibody levels

| Patient # | Pre-Hi Cy | Post-Hi Cy Minimum |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | 21.1 | 2.4 |

| #2 | 1.5 | 0.66 |

| #5 | 48.2 | 13.8 |

| #6 | 1.8 | 0 |

| #8 | 1.06 | 0 |

| #9 | 0.49 | 0 |

| #10 | 28.9 | 14.3 |

| #11 | 20.0 | 6.3 |

AChR antibody levels immediately before Hi Cy treatment and the minimum value after treatment. AChR antibodies fell following Hi Cy treatment in all patients.

FIGURE 2.

AChR antibody levels in patient #9, with fall following Hi Cy treatment and rise related to exacerbation. Retreatment with conventional immunosuppressive agents then resulted in a prompt fall of AChR antibody and clinical improvement.

Unrelated Antibodies—Tetanus and Diphtheria

In order to evaluate antibodies that are not related to the autoimmune disease, we measured tetanus and diphtheria antibodies in serum samples obtained before and after Hi Cy and at various times after re-immunization, in six of the patients. Two patients who received IVIg treatments (which contain exogenous antibodies) were excluded. The results are presented in Table 3. In four patients, the antibody levels fell after Hi Cy, and rose after re-immunization. In only two of the patients diphtheria antibodies fell to zero, but tetanus antibodies (which were higher than diphtheria antibodies) did not reach zero. In one patient (#3), there was no fall in either diphtheria or tetanus antibodies after Hi Cy, and he has not been re-immunized. These findings demonstrate that antibodies that are not related to the autoimmune disease behave similarly to the autoantibodies: they are moderately but incompletely reduced after Hi Cy treatment, and rise after antigen restimulation.

TABLE 3.

Tetanus and diphtheria antibodies

| Patient | Tetanus | Diphtheria | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Pre-Hi Cy | Post-Hi Cy | Post-Imm | Post-Imm 2 | Pre-Hi Cy | Post-Hi Cy | Post-Imm | Post-Imm 2 | |

| #1 | 0 | 0 | 3.16 | 1.48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| #2 | 5.78 | 5.23 | 9.12 | 6.41* | 0.65 | 0.46 | 1.7 | 0.88* |

| #3 | 7.43 | 7.69 | — | — | 1.26 | 1.62 | — | — |

| #4 | 3.20 | 1.93 | 8.92 | 6.76 | 1.49 | 1.17 | 1.68 | 1.45 |

| #5 | 2.35 | 1.3 | 3.79 | 3.21 | 0 | 0 | 0.42 | 0.3 |

| #8 | 6.14 | 0.96 | 4.8 | 5.39 | 1.45 | 0 | 0.92 | 1.2 |

Tetanus and diphtheria antibodies before and after Hi Cy and after re-immunization. Re-immunization was carried out beginning at 1 year after Hi Cy treatment, but the postimmunization levels were from serum obtained at various time intervals after the first or subsequent re-immunizations. Hi Cy produced reduction of these antibodies against exogenous antigens, but the changes were generally not dramatic. Patients produced antibodies in response to immune stimulation.

Indicates a later serum sample without repeat immunization.

TRECs

We were initially concerned that this group of myasthenic patients, who lacked thymus tissue due to therapeutic thymectomy from 1 to 14 years earlier, might not be able to reconstitute their T cell populations adequately following Hi Cy treatment. Since TRECs provide a measure of recent thymic emigrant T cells, such a deficit could be reflected in low TREC numbers. Although our data may be somewhat altered by immunosuppressive treatment, they clearly show that all patients produced TRECs after Hi Cy (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

TRECs (per 106 PBMC)

| Patient | Minimum | Time after Hi Cy (mos) | Maximum | Time after Hi Cy (mos) | Time at Exacerbation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | (675) | 60 | – | 78 | |

| #2 | 387 | 56 | 877 | 46 | |

| #3 | (1240) | 30 | – | 12 | |

| #4 | 323 | 35 | 1806 | 62 | |

| #5 | 147 | 10 | 4341 | 36 | |

| #6 | 80 | 4 | 1986 | 14 | |

| #7 | (412) | (pre) | – | ||

| #8 | 206 | 17 | 5983 | 27 | 36 |

| #9 | 2146 | 8 | 38540 | 9 | 5 |

| #10 | 3896 | 6 | 15350 | 8 | 17 |

| #11 | 3413 | 11 | 13259 | 1 | 5 |

| #12 | 953 | 8 | 1968 | 6 | |

| Nl #1 | (2688) | ||||

| Nl #2 | (2691) | ||||

| Nl #3 | (6796) | ||||

| Nl #4 | (4713) |

TRECs (Thymic receptor excision circles) per 106 PBMCs (peripheral blood mononuclear cells), determined as described in Methods. All 12 patients had TRECs measured; patients #1, 3, and 7, and all four controls had only one determination, at the time indicated (parentheses). Time of exacerbation is indicated in the last column. All patients were capable of producing TRECs after Hi Cy treatment. Patients # 8, 9, 10, and 11 had clinical exacerbations at times close to their maximum TREC levels, and these TREC levels were high in patients #9, 10, and 11.

Interestingly, TRECs increased to high levels in some, but not all, of the patients who developed exacerbations of MG after periods of clinical improvement. In two patients (#9, #11), the TRECs rose markedly at the time of the post-Hi Cy exacerbation. Patient #10 had a persistently high TREC level beginning 8 months after Hi Cy treatment, and developed an exacerbation of MG at 17 months (see Table 4). However, elevation of TRECs did not occur in all patients in relation to exacerbation of MG; Patient #8 had no rise in TRECs before exacerbation at 3 years.

Peripheral Blood Leukocytes

During the immediate post-Hi Cy period, the peripheral blood WBC fell markedly in all patients, but rose promptly within 3–12 days after beginning G-CSF injections. In six of the patients the WBC fell to <10 per mm3 at minimum, whereas the other six had somewhat higher minimum WBC levels, ranging from 42 to 160 per mm3. Most of the patients with the lowest minimum levels had the most favorable courses (#1, 2, 3, 4, 8). The one nonresponder (#6) had a minimum WBC of 42 during the immediate post-Hi Cy period, and the two patients with recurrence within 5 months had relatively high minimum levels of 50 and 160 per mm3. It is not clear whether the degree of reduction of leukocytes (which is difficult to measure at these low ranges) is related to the outcome of Hi Cy treatment.

Discussion

The results of this extended clinical study demonstrate that Hi Cy is a safe and powerful method for rebooting the immune system in myasthenic patients whose disease is refractory to conventional immunosuppressive therapies. Our results also reflect the aptness of the term “rebooting,” which implies that the immune system is favorably altered, but is not restored to its pristine state. (In terms of the computer analogy it is not “reformatted.”) We show that the effects of Hi Cy differ in individual patients, with some achieving durable—possibly even permanent—benefit, while others improve for variable periods of time, from 5 months to more than 7 years, and still others become responsive to conventional immunosuppressive treatments that had previously been ineffective.

We were initially concerned that ablation of the mature immune system by Hi Cy, in these special patients, might render them immunologically deficient because they lacked thymus glands as a result of therapeutic surgery. However, none of the patients had chronically increased susceptibility to infections after the immediate post-treatment period. Furthermore, they all developed and exported T cells, as determined by measurement of TRECs (Table 4) and lymphocyte subsets (data not shown). The continued presence of TRECs in thymectomized myasthenic patients has also been noted previously.19 Although TRECs are thought to represent T cells emigrating from the thymus,20 the site of origin of the exported T cells in these patients may be some alternative lymphoid organ.21

The concept underlying immunoablative treatment is that MG may result from the aberrant response of a genetically susceptible but otherwise normal immune system to some insult, as yet undetermined, that triggers the autoimmune response directed against AChRs or other components of the neuromuscular junction. If the immune system is basically normal, elimination of its autoreactive component should result in a “cure.” In principle, this could be accomplished by ablating the existing immune system completely and replacing it with a regenerated immune system that is totally purged of the autoreactive cells. Our observations suggest that these theoretical conditions are usually not met in practice. First, the patients with refractory MG that we have treated do not have normal immune systems. Both their failure to respond to conventional immunosuppressive agents, and the fact that the majority of patients had clinically significant autoimmune diseases in addition to MG, indicate that their immune systems have immunologic abnormalities in addition to autoimmune MG. Second, there is substantial evidence from animal experiments, as well as evidence from our observations in these patients, that complete immune ablation and replacement is unlikely to be achieved.

Previous experiments in our laboratory using Lewis rats with EAMG suggested that treatment with Hi Cy (200 mg/kg), and “rescue” with syngeneic bone marrow from unaffected rats could dramatically reduce the AChR antibody levels. However, when challenged with a boost of the AChR antigen, these rats developed an anamnestic response that was similar to, though not quite as high as, that in the untreated control EAMG rats.22 By contrast, combined treatment of the EAMG rats with both cyclophosphamide and total body irradiation (TBI), followed by bone marrow rescue, restored the rats to their pristine immunologic state.23 Not only were anti-AChR antibody levels reduced, but antibody responses to AChR antigen challenge were virtually identical to those of naive control rats. These EAMG studies demonstrated that Hi Cy alone effectively reduced the AChR antibody response, but left memory cells capable of responding to an antigen challenge. In the absence of antigen restimulation, the antibody response remained low, but when challenged with the antigen AChR the immune system developed a modified anamnestic response. The addition of TBI eliminated the memory cells, but required rescue by transplantation of syngeneic marrow. The use of this type of combined total myeloablative regimen in humans, with both Hi Cy and TBI, would result in a marked increase in morbidity and mortality, and would require the use of an autologous stem cell graft, which is highly likely to contain contaminating autoreactive lymphocytes as well.

The present results show that Hi Cy treatment probably does not produce total ablation of the existing mature immune system in our myasthenic patients, consistent with our previous findings in the experimental rats. Nearly all patients had persistent—although lowered—levels of both autoantibodies and unrelated antibodies to tetanus and diphtheria toxin. There is evidence that some memory lymphocytes express many stem cell characteristics,24,25 including resistance to cyclophosphamide due to elevated levels of aldehyde dehydrogenase.26 However, we have learned that even incomplete immune replacement can result in clinical benefit. It is likely that it “resets the immune thermostat” at a lower level, producing clinical improvement, restoring responsiveness to conventional immunosuppressive agents, and possibly inducing at least partial tolerance to the autoantigen.

We have examined several key aspects of the immune responses in our patients in order to attempt to identify patient factors that predict favorable and prolonged responses and to detect early clues to the onset of recurrence of clinical MG. (1) Neither gender nor age influenced the outcome of Hi Cy treatment in our limited sample; four of nine females and two of three males had the best clinical responses. Patients ranging in age from 27 to 67 years have achieved complete clinical remission for 17 years or more. (2) The pre-existing antibody status did not correlate with the outcome: of the six patients with the most favorable responses, four were AChR antibody positive (with levels ranging from 1.06 to 18.9 nM), one was MuSK antibody positive, and one was antibody negative. Three patients who did least well had AChR antibody levels from 0.49 to 20 nM. (3) There was a trend suggesting that completeness of leukocyte ablation after Hi Cy treatment may influence the outcome: most of the patients with the lowest minimum leukocyte levels after Hi Cy treatment had the best clinical courses, and three patients with the least favorable courses had higher minimum WBC levels after Hi Cy. (4) Clues to impending relapse of MG included either elevated levels of TRECs, or a rise of AChR antibodies in some of the patients.

Six of our patients developed clinical recurrence of MG from 5 months to 8 years after treatment with Hi Cy and complete or near-complete withdrawal of immunosuppressive medication. Three of these patients then responded well to conventional immunosuppressive medication which had previously been ineffective. In addition, one patient who relapsed after 3 years of Hi Cy–induced remission responded dramatically to retreatment with a second course of Hi Cy. Two other patients who had improved only modestly after Hi Cy, also became responsive to immunosuppressive agents which had not previously been effective. These observations suggest that continued treatment with moderate levels of conventional immunosuppressive agents after rebooting with Hi Cy may prevent recurrence in these patients. In other words, most of these refractory patients are not permanently “cured” by Hi Cy treatment, but they are restored to a status that is treatable with conventional immunosuppressive agents.

The patients that we have treated with Hi Cy have been selected for the severity of their MG and its lack of response to conventional treatment. In this sense, they represent a biased sample of the worst prospects for a “cure.” In fact, Hi Cy has produced long-lasting complete remissions when used earlier in the course of other autoimmune diseases, such as aplastic anemia27 and autoimmune hemolytic anemia.28 It is worth considering whether Hi Cy treatment might have more consistent and beneficial effects in patients who have ordinary MG. The risks inherent in this treatment regimen are very low, and it is conceivable that Hi Cy might result in rapid onset of improvement and long-lasting or permanent benefit in patients with garden-variety MG.

In summary, we have demonstrated that Hi Cy treatment is a safe and effective method for rebooting the immune system of patients with refractory MG. Based on our experience to date, we recommend that conventional immunosuppressive treatment, such as mycophenolate mofetil, be instituted as a follow-up to the acute Hi Cy treatment. Clearly, there are important questions that remain to be answered. We would like to know what factors can predict the effectiveness of Hi Cy treatment in myasthenic patients. Further experience will allow us to determine whether the newly recommended follow-up treatment with conventional immunosuppressive agents after Hi Cy will prevent relapse. Finally, the possibility of a role for Hi Cy in the treatment of nonrefractory MG will require careful consideration, and a well-designed trial.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Donna M. Dorr, RN, MSN, AOCN, for help in patient care and data collection and to G. Cruzeiras, Lead Scientist, Microbiology & Serology Program, Maryland Department of Health & Mental Hygiene for determination of antibodies to tetanus and diphtheria. We acknowledge support from the WW Smith Charitable Trust and National Institutes of Health NCI P01 CA 70970.

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement

Robert A. Brodsky and Richard J. Jones have the following statement to make: Under a licensing agreement between Accentia Pharmaceuticals and the Johns Hopkins University, Robert Brodsky and Richard Jones are entitled to a share of royalty received by the university on sales of intellectual property (Revimmune). The study described in this article could have an impact on the value of Revimmune. The terms of this arrangement are being managed by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

References

- 1.Drachman DB. Myasthenia gravis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1797–1810. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406233302507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent A, Drachman DB. Myasthenia gravis. Adv Neurol. 2002;88:159–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toyka KV, Drachman DB, Griffin DE, et al. Myasthenia gravis. Study of humoral immune mechanisms by passive transfer to mice. N Engl J Med. 1977;296:125–131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197701202960301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoch W, McConville J, Helms S, et al. Auto-antibodies to the receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK in patients with myasthenia gravis without acetylcholine receptor antibodies. Nat Med. 2001;7:365–368. doi: 10.1038/85520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanders D, El-Salem K, Irbid J, et al. Muscle specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) positive, seronegtive myasthenia gravis (SN-MG). Clinical characteristics and response to therapy. Neurology. 2003;60(Suppl 1):A418. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou L, McConville J, Chaudhry V, et al. Clinical comparison of muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) antibody-positive and -negative myasthenic patients. Muscle Nerve. 2004;30:55–60. doi: 10.1002/mus.20069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drachman DB. Therapy of myasthenia gravis. In: Engel AG, editor. Neuromuscular Junction Disorders; Handbook of Neurology. Elsevier; London: 2008. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drachman DB, Jones RJ, Brodsky RA. Treatment of refractory myasthenia: “Rebooting” with high-dose cyclophosphamide. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:29–34. doi: 10.1002/ana.10400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brodsky RA, Petri M, Smith BD, et al. Immunoablative high-dose cyclophosphamide without stem-cell rescue for refractory, severe autoimmune disease. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:1031–1035. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-12-199812150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brodsky RA, Jones RJ. High-dose cyclophosphamide in aplastic anaemia. Lancet. 2001;357:1128–1129. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brodsky RA, Chen AR, Brodsky I, Jones RJ. High-dose cyclophosphamide as salvage therapy for severe aplastic anemia. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:435–440. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drachman DB, Brodsky RA. High-dose therapy for autoimmune neurologic diseases. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17:83–88. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000152974.65477.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon MY, Goldman JM, Gordon-Smith EC. 4-Hydroperoxycyclophosphamide inhibits proliferation by human granulocyte-macrophage colony-forming cells (GM-CFC) but spares more primitive progenitor cells. Leuk Res. 1985;9:1017–1021. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(85)90072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kastan MB, Schlaffer E, Russo JE, et al. Direct demonstration of elevated aldehyde dehydrogenase in human hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 1990;75:1947–1950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones RJ, Barber JP, Vala MS, et al. Assessment of aldehyde dehydrogenase in viable cells. Blood. 1995;85:2742–2746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaretzki A, Barohn RJ, Ernstoff RM, et al. Myasthenia gravis: recommendations for clinical research standards. Task Force of the Medical Scientific Advisory Board of the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America. Neurology. 2000;55:16–23. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schag CC, Heinrich RL, Ganz PA. Karnofsky performance status revisited: reliability, validity, and guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2:187–193. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Douek DC, McFarland RD, Keiser PH, et al. Changes in thymic function with age and during the treatment of HIV infection. Nature. 1998;396:690–695. doi: 10.1038/25374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sempowski G, Thomasch J, Gooding M, et al. Effect of thymectomy on human peripheral blood T cell pools in myasthenia gravis. J Immunol. 2001;166:2808–2817. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geenen V, Poulin JF, Dion ML, et al. Quantification of T cell receptor rearrangement excision circles to estimate thymic function: an important new tool for endocrine-immune physiology. J Endocrinol. 2003;176:305–311. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1760305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez S, Nolan RC, Price P, et al. Thymic function in severely immunodeficient HIV type 1-infected patients receiving stable and effective antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006;22:163–170. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pestronk A, Drachman DB, Adams RN. Treatment of ongoing experimental myasthenia gravis with short term high dose cyclophosphamide. Muscle Nerve. 1982;5:79–84. doi: 10.1002/mus.880050115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pestronk A, Drachman DB, Teoh R, Adams RN. Combined short-term immunotherapy for experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis. Ann Neurol. 1983;14:235–241. doi: 10.1002/ana.410140210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luckey CJ, Bhattacharya D, Goldrath AW, et al. Memory T and memory B cells share a transcriptional program of self-renewal with long-term hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3304–3309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511137103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, Joe G, Hexner E, et al. Host-reactive CD8+ memory stem cells in graft-versus-host disease. Nat Med. 2005;11:1299–1305. doi: 10.1038/nm1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsui W, Wang Q, Barber JP, et al. Clonogenic multiple myeloma progenitors, stem cell properties, and drug resistance. Cancer Res. 2008;68:190–197. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brodsky RA, Sensenbrenner LL, Smith BD, et al. Durable treatment-free remission after high-dose cyclophosphamide therapy for previously untreated severe aplastic anemia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:477–483. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-7-200110020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moyo V, Smith B, Brodsky I, et al. High-dose cyclophosphamide for refractory autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Blood. 2002;100:704–706. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]