Abstract

Purpose

In this study, the authors examined the linguistic profile of African American English (AAE)-speaking children reared in poverty by focusing on their marking of passive participles and by comparing the results with the authors’ previous study of homophonous forms of past tense (S. Pruitt & J. Oetting, 2009).

Method

The data were from 45 five- to six-year-olds who spoke AAE and who participated in the authors’ earlier study. Fifteen were classified as low-income (LSES); the others were classified as middle-income and served as either age- or language-matched controls. The data came from a probe that was designed by S. M. Redmond (2003), but it was modified to examine the morphological and phonological characteristics of AAE.

Results

Participle marking by all 3 groups was influenced by AAE phonology, but the LSES children marked the participles at lower rates than the controls. The LSES children’s rates of participle marking were also lower than their rates of marking for homophonous forms of past tense. Unlike the children’s rates of past-tense marking, their rates of participle marking were correlated to their vocabulary test scores.

Conclusions

AAE-speaking children reared in poverty present weaknesses in aspects of grammatical morphology that are related to their vocabulary weaknesses.

Keywords: African American English, low-income, passive participle, vocabulary weaknesses

Children reared in poverty, as a group, score below the national average on standardized language tests (Chaney, 1994; Dickinson, McCabe, Anastasopoulos, Peisner-Feinberg, & Poe, 2003; Dollaghan et al., 1999; Fazio, Naremore, & Connell, 1996; Gilliam & de Mesquita, 2000; Heath, 1983; Qi, Kaiser, Milan, & Hancock, 2006; Washington & Craig, 1994, 1999; Whitehurst, 1997). Although poverty can affect children of all ethnic and racial backgrounds, a substantial amount of research has focused on low-income children who are African American and speak African American English (AAE). This is in part because a disproportionate rate of African Americans relative to European Americans live in poverty (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, & Smith, 2009), and low-income African American children score lower than low-income European American children on standardized test measures (Restrepo et al., 2006).

AAE-speaking children who are reared in poverty and score low on standardized language tests are particularly difficult for speech-language pathologists to assess because there are at least three explanations for these children’s low test scores: test biases that penalize children who speak AAE, an impoverished language environment, and a faulty language learning system. Of these three explanations, only the third warrants a clinical diagnosis of language impairment.

Over the past 15 years, there has been a growing number of studies on nonbiased assessment methods for AAE-speaking children and on the linguistic profiles of AAE-speaking children who present with a clinical diagnosis of language impairment (e.g., Campbell, Dollaghan, Needleman, & Janosky, 1997; Cleveland, 2009; Craig & Washington, 2000; de Villiers, Roeper, Bland-Stewart, & Pearson, 2008; Garrity & Oetting, 2010; Johnson & de Villiers, 2009; Laing & Kamhi, 2003; Oetting, Cantrell, & Horohov, 1999; Oetting, Cleveland, & Cope, 2008; Oetting & Horohov, 1997; Oetting & McDonald, 2001; Oetting & Newkirk, 2008; Peña, Iglesias, & Lidz, 2001; Peña & Quinn, 1997; Seymour, Bland-Stewart, & Green, 1998). Far less is known about the linguistic strengths and weaknesses of AAE-speaking children who are not receiving (and are not perceived as needing) speech and language therapy, but who nonetheless have been reared in poverty and earn low language test scores. This is unfortunate because without detailed information about these children’s language profiles, speech-language pathologists have little to offer these children and their families.

In an effort to learn more about the linguistic strengths and weaknesses of low-income AAE-speaking children, Pruitt and Oetting (2009) conducted a study that focused on past tense. The participants included low-income children who presented low vocabulary test scores and middle-income children who served as age- and language-matched controls. Past tense was examined because other groups of children who score low on standardized tests, such as those with clinical language impairments, have repeatedly been shown to present difficulties with this structure (Tager-Flusberg & Cooper, 1999). Also, sufficient detail about the AAE past-tense system was available in the dialect literature to guide the work (Green, 2002; Oetting & McDonald, 2001; Rickford, 1999; Seymour et al., 1998).

The results showed that the low-income children presented age-appropriate past-tense marking even though their standardized vocabulary test scores were identified as below average. In fact, both the AAE-speaking children reared in poverty and both groups of controls produced relatively high rates of past-tense marking while also showing higher rates of marking for verbs ending in vowels (e.g., dry) as compared with verbs ending in consonants (e.g., kick). High rates of past-tense marking and this particular pattern of results for phonology are consistent with what has been documented in the adult AAE literature (Rickford, 1999).1

On the basis of these findings, we concluded that the language effects of poverty (as defined as below-average vocabulary test scores) do not necessarily include weaknesses with grammatical morphology. Using data from the same children who participated in Pruitt and Oetting (2009), we extended our analysis in the present study to children’s use of passive participles. The participles examined were those that were homophonous with the past-tense forms we previously studied. To illustrate the homophonous nature of these structures, compare the passive participle in The dog was brushed by Billy with the past tense in Billy brushed the dog.

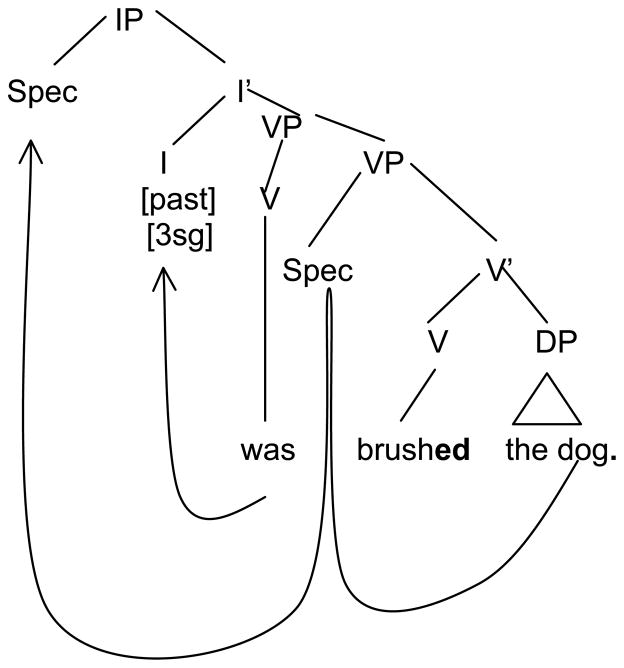

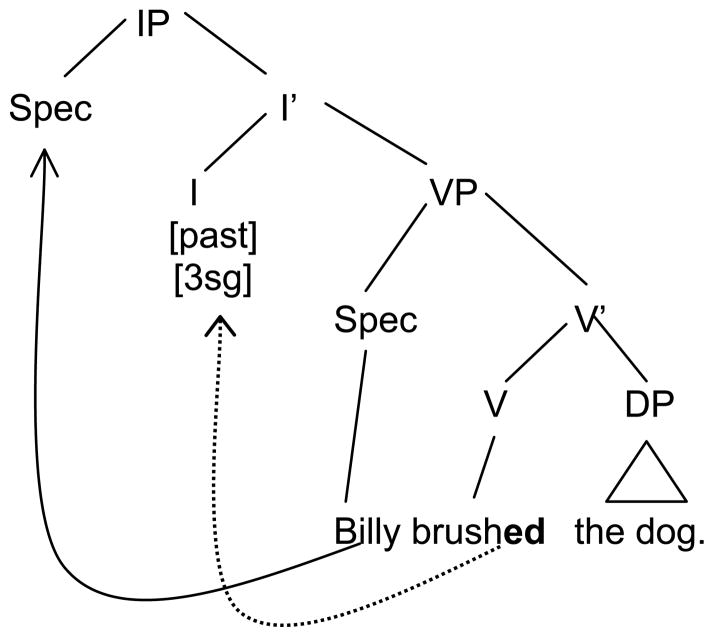

Although there is debate as to the underlying grammar of various types of passives (e.g., adjectival passives, be-passive, get-passive; for review, see Smith-Lock, 1992; see also Guasti, 2002), based on the syntactic theory, we predicted that AAE-speaking children reared in poverty would mark passive participles at rates that were similar to those of middle-income controls and similar to their own rates of past-tense marking. These predictions were based on the assumption that passive participles and past-tense structures both involve subject raising to the specifier of the inflectional phrase (IP) in a verb phrase (VP) – inflectional phrase (IP) clause (Chomsky, 1986, 1993, 1995). This raising (i.e., movement) is illustrated in Figure 1 for the passive participle and in Figure 2 for past tense. For the passive, The dog (direct object) moves to the specifier of IP (perhaps through the specifier of the VP, accounting for quantifier stranding in examples like The dogs were all brushed), whereas in the active sentence involving past tense, Billy (subject) moves directly to the specifier of IP. Both structures also require movement of the tensed verb to I. For the passive, this movement is overt movement of the tensed auxiliary verb (i.e., was to I). For the active, this movement is covert movement of the main verb (i.e., brushed to I).2 Although the noun phrase (NP) movement chain is slightly longer for passive sentences than it is for active sentences with a past-tense structure, the V movement in active sentences is slightly longer than it is for passive sentences. Nothing in syntactic theory would suggest that these differences should affect the ease with which children learn and produce participle and past-tense structures.

Figure 1.

Tree diagram for a sentence with a passive participle form. IP = inflectional phrase; I = inflection; VP = verb phrase; DP = determiner phrase.

Figure 2.

Tree diagram for a sentence with a past tense form (covert movement is indicated by dotted line).

Finally, participle and past-tense structures both require tense and agreement checking in I after the tensed verb moves to I (whether overtly or covertly). In the passive, tense and agreement are encoded on was, and in the active, tense and agreement are encoded on brushed through the –ed affix. These differences have been used to explain why children with clinical language impairments have more difficulty with the past-tense –ed affix than the passive participle –ed affix (Redmond, 2003). For children reared in poverty, however, the important point is that checking does not occur at the site of the passive participle –ed affix. Given this, syntactic theory would not predict passive –ed affixes to be more difficult than past-tense –ed affixes.

Interestingly, though, there are aspects of passive participles that may make these forms difficult for children reared in poverty, especially if the children present vocabulary weaknesses that are tied to an impoverished language-learning environment. For example, passive participles are produced less frequently than past tense in spoken English. In fact, Redmond (2003) found that in spontaneous speech, children were twice as likely to produce a past-tense form as a passive participle form (for more details about the frequency of passive participles, see Brown, 1973; Gordon & Chafetz, 1990).

The production of passive participles also draws heavily on a speaker’s lexicon because of the various classes of participles that exist at the level of morphophonology. As identified in Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech, and Svartvik (1985), the various classes include (a) regular verbs that have the same past and participle forms (e.g., call/called/called); (b) irregular verbs that have the same past and participle forms (e.g., meet/met/met); (c) irregular verbs that have the same present, past, and participle forms (e.g., cut/cut/cut); (d) irregular verbs that have the same present and past forms but a different participle form (e.g., beat/beat/beaten); (e) irregular verbs that have the same present and participle forms but a different past form (e.g., come/came/come); and (f) irregular verbs that have different present, past, and participle forms (e.g., choose/chose/chosen). The lexical complexity of passive participles coupled with their low frequency in the input may make these structures difficult for children reared in poverty, especially if these children present low vocabulary abilities that are tied to their low-income backgrounds. A study of passive participles is needed to test this hypothesis.

The homophonous nature of some passive participle forms and some past-tense forms also allows for an additional test of the effects of AAE phonology on children’s marking of grammatical morphology. Green (2002) stated that adult AAE speakers do not always make a distinction between participle and past-tense forms, even when in mainstream American English, the participle form and the past-tense form differ from one another. As an example, Green described drunk as both the participle and past-tense form of drink within adult AAE as opposed to the two forms drank and drunk that are produced in mainstream American English.

Support for Green’s (2002) description of AAE with child data can be found in Oetting and McDonald (2001), because in that study, child AAE speakers also produced a number of homophonous participle and past-tense forms (e.g., kicked, ated, drunk, break). As can be seen by these examples, the surface marking of the children’s participles included the –ed affix on regular and irregular verbs as well as nonstandard marking and bare stems (which in nonmainstream dialects of English are referred to as zero-marked forms).3 Given these characteristics of the AAE participle and past-tense systems, we predicted that effects of AAE phonology on the children’s marking of passive participles would be identical to those observed for past-tense marking.

In summary, there is some evidence to suggest that AAE-speaking children reared in poverty and who show weaknesses in vocabulary present age-appropriate grammatical morphology and a morphological system that is influenced by the same phonological constraints as adult speakers of AAE. The study of passive participles offers an additional test of these findings. The questions guiding the study were (a) Do AAE-speaking children reared in poverty mark passive participle forms at the same rate as middle-income AAE-speaking controls? (b) Do AAE-speaking children reared in poverty mark passive participles at the same rate as they mark homophonous forms of past tense? and (c) Are AAE-speaking children’s marking of passive participles affected by the same phonological characteristics that affect their marking of past tense?

Method

Participants

Forty-five African American and AAE-speaking children who participated in Pruitt and Oetting (2009) contributed data to the analysis. Details regarding the participants and the participant selection process can be found in the original article, but general information about them is as follows: The participants included 18 males and 27 females. The children’s status as AAE speakers and their rates of nonstandard English use was confirmed through blind listener judgments using Oetting and McDonald’s (2002) 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (rater perceived no use of nonstandard English) to 7 (rater perceived heavy use of nonstandard English). All of the speakers earned a nonstandard dialect rating of 2 or higher, which confirmed their status as AAE speakers.

Fifteen of the children were classified as low-income (LSES), 15 were classified as middle-income, age-matched controls (AM), and 15 were classified as middle-income, language-matched controls who were matched to those in the LSES group on vocabulary (LM). Children assigned to the LSES and AM groups were 6 years of age and in kindergarten (LSES mean age = 73.47 months, SD = 4.02; AM mean age = 71.80, SD = 2.21), and those assigned to the LM group were 5 years of age and enrolled in preschools (LM mean age = 59.00, SD = 5.26). Socioeconomic status levels were defined on the basis of maternal education. The LSES group had mothers who had not graduated from high school, and the AM and LM groups had mothers who had completed at least 2 years of college.

Given that other groups of children from low-income homes have been shown to present low scores on standardized language tests (Dollaghan et al., 1999; Washington & Craig, 1999), the children in the LSES group were required to earn standard scores that were less than 90 on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—III (PPVT–III; Dunn & Dunn, 1997), and the children in the AM and LM groups were required to earn scores that were greater than 90. The use of 90 as the criterion for the PPVT–III was based on the group average (M = 91, SD = 11) of the African American participants included in Washington and Craig’s (1999) study of the PPVT–III. The children in the LSES and AM groups also did not attend the same schools. Instead, most of the children in the LSES group attended schools with standardized test scores that fell below the state average, whereas most of the children in the AM group attended schools with above-average test scores.

As summarized in Table 1, additional measures were used to document the children’s cognitive, speech, and language abilities. These were an articulation screener that examined /t/ and /d/ in singletons and clusters; the Figure Ground and Form Completion subtests of the Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised (LEITER-R; Roid & Miller, 1998); Subtests IV–VI of the Test of Language Development—Primary, Third Edition (TOLD–P:3; Hammill & Newcomer, 1997); and mean length of utterance (MLU) from a spontaneous language sample. All children passed the articulation screener with 90% accuracy, and an analysis of variance indicated that the groups did not differ for MLU, F(2, 44) = 2.37, p = .11. Given the selection criteria, the three groups differed on their PPVT–III standard scores, F(2, 44) = 45.81, p < .001, and they also differed on the LEITER-R, F(2, 44) = 15.36, p = .01; TOLD–P:3, F(2, 44) = 12.60, p < .001, and nonstandard dialect density ratings, F(2, 44) = 9.20, p = .003. For all three standardized tests, post hoc t tests revealed that the scores of the children in the LSES group were lower than those of both control groups, but for dialect density, the LSES group earned higher nonstandard ratings than both control groups (p < .05; for details, see Pruitt & Oetting, 2009).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics: Group means and (standard deviations).

| Group | Agea | Artic screenerb | Maternal edc | PPVT–III standardd | PPVT–III rawe | LEITER-Rf | TOLD–P:3g | MLUh | AAE ratingi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSES | 73.47 (4.02) | 9.93 (0.26) | 10 (1.41) | 80.27 (6.60) | 57.13 (8.94) | 9.47 (1.55) | 81.13 (15.27) | 6.49 (1.38) | 5.58 (1.03) |

| AM | 71.80 (2.21) | 10.00 (—) | 15.60 (0.63) | 102.87 (7.12) | 83.93 (9.90) | 10.73 (1.82) | 100.27 (7.58) | 6.64 (1.06) | 4.24 (1.26) |

| LM | 59.00 (5.26) | 9.73 (0.46) | 15.60 (0.74) | 99.73 (7.29) | 63.23 (11.42) | 11.47 (2.00) | 100.27 (12.04) | 5.96 (0.92) | 4.20 (1.17) |

Note. Em dash in third column indicates that there was no variability (all children scored 10 out of 10). PPVT–III = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—III; LEITER-R = Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised; TOLD–P:3 = Test of Language Development—Primary, Third Edition; MLU = mean length of utterance; AAE = African American English; LSES = low income; AM = middle-income age matched; LM = middle-income language matched.

Age: In months.

Artic screener: Screening tool for final /t/ and /d/ in singletons and clusters, highest score = 10.

Maternal ed: Highest grade completed, 12 = graduated from high school, 16 = graduated from college.

PPVT–III standard: Standard score obtained on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—III, used for eligibility.

PPVT–III raw: Raw score obtained on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—III, used for matching LSES and LM groups.

Leiter-R: Average scaled scores from the Figure Ground and Form Completion subtests of the Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised (M = 10, SD = 3).

TOLD–P:3: Syntax quotient calculated from subtests IV–VI of the Test of Language Development—Primary, Third Edition (M = 100, SD = 15).

MLU: Mean length of utterance in morphemes based on complete and intelligible utterances from language sample.

AAE rating: Rating averaged across three listeners; 1 = no use of AAE; 7 = heavy use of AAE (Oetting & McDonald, 2002).

From “Past Tense Marking by African American English-Speaking Children Reared in Poverty,” by S. Pruitt and J. Oetting, 2009, Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52, 2–15. Copyright 2009 by American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

Materials

Following Redmond (2003), a probe was created to elicit the children’s passive participle forms, but the verbs were selected for their phonology and were identical to those used by Pruitt and Oetting (2009). Seven of the verbs were considered more likely to result in overt marking by AAE-speaking children because the verb root ended with a vowel (i.e., dry, play, tie, glue, fry, chew, and show), and seven were considered less likely to result in overt marking by AAE-speaking children because they required the [-t] or [-d] allomorph and the verb root ended with a consonant (i.e., kick, color, pour, open, pop, pick, and brush).

In order to make the task demands of the participle probe as similar to the past-tense probe as possible, the same videotaped actions and procedures were used as in Pruitt and Oetting (2009). Each video clip presented a young woman completing an action (e.g., bouncing a ball), and while each video clip played, the examiner presented a verbal prompt in live voice (e.g., “She is bouncing a ball. She is bouncing a ball. Now she is done bouncing a ball. The ball ___.”). The videotaped clip remained frozen on the screen after presentation to provide the children with a visual reminder of the action when responding. Both full (e.g., The ball was bounced by the girl) and truncated passives (e.g., The ball was bounced) were accepted from the children.

Reliability

Approximately 20% of the probe data were independently transcribed and coded by a second set of examiners. Agreement was calculated for the probe by dividing the total number of agreements by the total number of agreements and disagreements. This yielded interrater agreement rates of 90% for the passive participle probe.

Results

The children’s responses were classified as standard marked (e.g., brushed), nonstandard marked (e.g., brusheded), or zero marked (e.g., brush). The nonstandard marked category was based on descriptive accounts of AAE that indicate this dialect allows for both standard and nonstandard expressions of passive participles (Green, 2002). Responses that did not fall into the standard, nonstandard marked, or zero-marked categories were classified as “other.” These included present progressive sentence frames for targets (e.g., She brushing), the use of a different verb (e.g., The dog was combed by the girl for The dog was brushed by the girl), “I don’t know,” and no responses. In no case did the children produce the simple past during the passive task (e.g., The dog brushed).

We calculated the children’s percentage of overtly marked passive participles using the following formula: (standard marked + nonstandard marked)/(standard marked + nonstandard marked + zero marked). All statistical analyses were conducted on the children’s rates of overt marking. Given that these data came from a probe and the number of opportunities for producing a marked form was fixed, we conducted arcsine transformations prior to the analyses.

Participle Marking by Group and AAE Phonology

As shown in Table 2, the majority of the children’s verbs were classified as standard marked, but there were 89 responses that reflected nonstandard English patterns. These nonstandard patterns made up 14% of the children’s responses (13% for the LSES group, 11% for the AM group, and 18% for the LM group).4 Examples of some of the nonstandard marked forms included bounceded, fryened, dryened, playeded, pourned. Importantly, all three groups produced these nonstandard responses, and as mentioned earlier, these responses were considered overtly marked participle forms.

Table 2.

Passive participle marking: Higher probability versus lower probability verbs.a

| Group | Higher probability

|

Lower probability

|

Total

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | Nonstandard | Zero marked | Other | % markedb | Standard | Nonstandard | Zero marked | Other | % marked | % marked | |

| LSES | 4.13c (2.13) | 0.60 (0.83) | 0.93 (1.16) | 1.33 (1.17) | 81% (23.96) | 3.13 (1.85) | 1.27 (1.87) | 1.93 (1.44) | 0.67 (0.90) | 69% (23.83) | 74% (22.19) |

| AM | 6.73 (1.03) | 0 (—) | 0.20 (0.56) | 0.13 (0.52) | 96% (10.60) | 4.53 (2.39) | 1.53 (2.26) | 0.73 (0.80) | 0.20 (0.56) | 89% (12.00) | 93% (10.10) |

| LM | 4.47 (2.53) | 1.13 (2.23) | 0.67 (1.05) | 0.67 (1.54) | 89% (17.05) | 4.13 (2.64) | 1.40 (2.13) | 0.93 (1.44) | 0.53 (0.80) | 85% (22.67) | 88% (18.13) |

Note. Standard deviations appear in parentheses.

Maximum total for probe = 14 (7 = high probability and 7 = low probability).

% marked = calculated from (standard marked + nonstandard marked)/(standard marked + nonstandard marked + zero marked).

The first value reflects the group mean; values in parentheses reflect the standard deviations.

To analyze the children’s rates of overtly marked participles, we completed a mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA), with group (LSES, AM, LM) as a between-subjects variable and verb type (higher probability AAE phonology, lower probability AAE phonology) as a within-subjects variable. We observed a significant main effect for group, F(2, 42) = 4.18, p = .02, η2 = .17, and a follow-up Tukey’s honestly significant difference test indicated that the children in the LSES group (M = 74%) marked passive participles at a lower rate than the children in the AM (M = 93%) and LM (M = 88%) groups. Group differences were not found between the AM and LM groups. Also, we observed a significant main effect for verb type, F(1, 42) = 18.27, p < .001, η2 = .30. Across groups, marking of passive participles was greater for the higher probability AAE phonology verbs (M = 89%) than for the lower probability AAE phonology verbs (M = 81%). Given that the verb type manipulation did not interact with the grouping variable, we conducted the remaining analyses with the higher and lower probability verbs collapsed.

Participle Marking Versus Past-Tense Marking

Table 3 presents the children’s rates of marking for the current set of participles to their previously studied rates of past-tense marking. To compare the children’s marking of these two types of grammatical structures, we completed a mixed-model ANOVA, with group (LSES, AM, LM) as the between-subjects variable and morpheme type (participle, past tense) as the within-subjects variable. Again, we observed a significant main effect for group, F(2, 42) = 3.96, p = .03, η2 = .16, but this was qualified by a significant interaction between group and morpheme type, F(2, 42) = 3.46, p = .04, η2 = .14. Follow-up analysis of this interaction indicated that the groups differed in their marking of the participles, F(2, 44) = 4.99, p = .01, η2 = .19, but not in their marking of past tense, F(2, 44) = 2.429, p = .10. Follow-up of the group effect for the participles was identical to what was reported in the earlier analysis, with the LSES group presenting a lower rate of marking than the other two groups. Also, the children in the LSES group (but not the AM and LM groups) presented a lower rate of marking for participles than for past tense: LSES, t(14) = 2.095, p = .05, d = 0.59; AM, t(14) = 0.502, p = .62; LM, t(14) = −1.554, p = .14.

Table 3.

Passive participle and past-tense marking.

| Group | Passive participle (present study)

|

Past tense (Pruitt & Oetting, 2009)

|

|---|---|---|

| % markeda | % marked | |

| LSES | 74%b (22.19) | 85% (14.06) |

| AM | 93% (10.10) | 94% (9.16) |

| LM | 88% (18.13) | 85% (17.06) |

% marked = calculated from (standard marked + nonstandard marked)/(standard marked + nonstandard marked + zero marked).

The first value reflects the group mean; the values in parentheses reflect the standard deviations.

Correlational Analysis

To determine whether the children’s overt marking of passive participle forms were related to other aspects of their language and cognitive skills and/or to their mothers’ level of education, we conducted a correlational analysis. As shown in Table 4, the children’s marking of passive participle forms was positively related to the children’s marking of past tense. In addition, the children’s marking of passive participles was positively related to their PPVT–III and TOLD–P:3 scores, MLU, and mother’s education levels and negatively related to their AAE dialect ratings as measured by the listener judgment task. These findings differ from what was found for the children’s marking of past tense, as the children’s past-tense marking was not correlated to any of these measures.

Table 4.

Relationship between passive participle, past tense, and other aspects of language, cognition, and maternal education.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Passive participle | — | .49** | .41** | .36* | .36* | .08 | .37* |

| 2. Past tense | — | .13 | .15 | .26 | −.18 | −.09 | |

| 3. PPVT–III | — | .73** | −.06 | .37* | .75** | ||

| 4. TOLD–P:3 | — | .29 | −.03 | −.20 | |||

| 5. MLU | — | −.03 | −.20 | ||||

| 6. LEITER-R | — | .37* | |||||

| 7. Maternal education | — |

p < .05.

p < .001.

Discussion

In a previous study, Pruitt and Oetting (2009) showed that AAE-speaking children reared in poverty present age-appropriate rates of past-tense marking even though their vocabulary test scores were below average. In the present study, we extended our analyses to these same children’s marking of passive participles. Although passive participles and past-tense forms both require movement within a VP-IP clause, the former are less frequent in spoken English and present more lexical complexity than the latter. Given this, we wondered whether AAE-speaking children reared in poverty who present weaknesses in vocabulary would find passive participles difficult to acquire and use. To examine this question, we compared low-income children’s rates of participle marking with those of middle-income controls and with their own rates of past-tense marking. By using a set of participles that were homophonous to a previously studied set of past-tense forms, we also examined the effects of AAE phonology on the children’s marking of the participles.

Results showed that the AAE-speaking children reared in poverty overtly marked participles at lower rates than their middle-income peers. Rates of participle marking by the AAE-speaking children reared in poverty were also lower than their rates of past-tense marking. This pattern of findings (i.e., participles < past tense) was not observed for the middle-income controls. Together, these findings indicate that the marking of passive participles is an area of weakness for children reared in poverty.

All three groups of AAE speakers also varied their marking of passive participles as a function of the phonological characteristics of the items, and the direction of the influence was consistent with what has been documented in the adult AAE literature. These results support our previous findings for the children’s marking of past tense, and together they attest to the phonological as opposed to morphological nature of the influence. Descriptive accounts of adult AAE by Green (2002) and others also interpret these types of effects as related to consonant cluster reductions within the phonology of AAE. The present work and our previous study of past tense provide empirical evidence with child data to support this claim.

Finally, given the low frequency and lexical complexity of passive participles, it seems possible that these children’s difficulty with this structure is tied to their vocabulary weaknesses. To further test the relation between the children’s marking of passive participles and their vocabulary abilities, we completed a series of correlations and found that the children’s marking of passive participles was positively related to their marking of past tense. This is not surprising given that the two structures require a similar amount and type of syntactic complexity. However, unlike the children’s marking of past tense, their marking of passive participles was positively related to their maternal education levels and to a number of the language measures we collected, and these measures included the children’s vocabulary test scores. These findings support our hypothesis that the low-income children’s difficulty with passive participles is related to their weaknesses in vocabulary.

The present findings for children reared in poverty and those previously documented for these same children’s past-tense systems also suggest that some grammar structures (i.e., participles) are more dependent on a child’s lexicon than on others (i.e., past tense). Interestingly, studies conducted using children with specific language impairment as participants have also suggested this even though the impetus and focus of those studies have differed from the present work (see Rice, 2004, 2006; Rice, Tomblin, Hoffman, Richman, & Marquis, 2004; Rice & Wexler, 1996; Rice, Wexler, & Cleave, 1995; Rice, Wexler, & Hershberger; 1998; for studies that include passive participles, see Leonard et al., 2003; Redmond, 2003; Smith-Lock, 1992).

Nevertheless, additional studies are needed to further explore the present findings for children reared in poverty. Future studies should include other grammatical structures that vary in their syntactic, semantic, and phonological properties as well as other groups of children who are reared in poverty and who present varying degrees of vocabulary ability. This type of work need not be limited to AAE-speaking children because children reared in poverty speak a range of dialects and, in some cases, a range of first and second languages. However, key to this type of research is the need for clinical impairments to be ruled out as the source of the low-income children’s low test scores. For group comparison studies, researchers should also ensure that the children reared in poverty are matched to middle-income controls who speak a similar type of dialect and/or similar type of first and/or second language. Benefits of this work should include a better understanding of the language needs of children reared in poverty across dialects and languages and a better understanding of the different ways in which children’s language systems can be compromised for various reasons (i.e., poverty, speech and language impairment, etc).

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by a graduate student assistantship and Foundation Research Account from Louisiana State University. During the completion of this study, the second and third authors were funded by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant RO1DC00981. These data were also presented at the 2007 annual convention of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Boston, MA. Gratitude is extended to Elicia Gilbert for assistance with the stimuli and to April Garrity for assistance with the reliability. We also thank the teachers, parents, and children who made the research possible.

Footnotes

This particular pattern for AAE phonology is in contrast to what has been documented for mainstream American English-speaking 6-year-olds, because by age 6, mainstream American English-speaking children mark verbs ending in vowels and consonants at extremely high rates (e.g., 97%, as documented by Oetting & Horohov, 1997; for additional evidence, see Marshall & van der Lely, 2007).

For past tense, the movement of V to I could alternatively be described as affix lowering of the tense and subject agreement features of I to V. But in that case, the two options (V-to-I raising of was in the passive, and I-to-V lowering of the affix onto the main verb in the active) would have the same derivational complexity, so the affix-lowering analysis would provide no grounds to expect that the passive participle should be harder for a child to learn and use than the past-tense marker. We adopt, instead, the distributed morphology framework of Halle and Marantz (1993), where feature bundles for each affix are generated in appropriate functional categories and are spelled out phonologically on their appropriate stems, which dispenses with affix lowering in favor of uniform raising of the tensed verb to I, whether overtly or covertly. On this view also, as discussed here in connection with Figures 1 and 2, there is no derivational difference between the two sentences that would lead us to expect any difference in the learning and use of the passive participle, relative to the past-tense marker.

Although young children learning mainstream American English have also been documented to produce passive participles with the –ed affix on regular and irregular verbs and with bare stems, again by the age of 6, these types of passive participle productions are infrequent (for raw data, see Redmond, 2003) and are thought to occur less frequently than what has been documented in child and adult AAE.

The proportion of nonstandard participle responses by the LM group is visually higher than those of the other two groups. Perhaps this is because the LM group is younger than the others and in a stage at which their morphological systems are overregularizing the –ed affix, as is common in young children acquiring other dialects of English, such as mainstream American English. Although this could certainly be the case, the effect appears structure specific because the LM group did not produce any of these types of nonstandard (i.e., overregularized) responses with these same regular verbs during the past-tense probe.

References

- Brown R. A first language: The early stages. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell T, Dollaghan C, Needleman H, Janosky J. Reducing bias in language assessment: Processing-dependent measures. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1997;40:519–525. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4003.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaney C. Language development, metalinguistic awareness, and emergent literary skills of 3-year-old children in relation to social class. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1994;15:371–394. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky N. Barriers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky N. A minimalist program for linguistic theory. In: Hale K, Keyser SJ, editors. The view from building. Vol. 20. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1993. pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky N. The minimalist program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland LH. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Louisiana State University; Baton Rouge: 2009. Children’s verbal –s marking by dialect type and clinical status. [Google Scholar]

- Craig HK, Washington JA. An assessment battery for identifying language impairments in African American children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2000;43:366–379. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4302.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. US Census Bureau, Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2009. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers J, Roeper T, Bland-Stewart L, Pearson BZ. Answering hard questions: Wh movement across dialects and disorder. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2008;29:67–103. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson DK, McCabe A, Anastasopoulos L, Peisner-Feinberg ES, Poe MD. The comprehensive language approach to early literacy: The interrelationships among vocabulary, phonological sensitivity, and print knowledge among preschool-aged children. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2003;95:465–481. [Google Scholar]

- Dollaghan CA, Campbell TF, Paradise JL, Feldman HM, Janosky JE, Pitcairn DN, Kurs-Lasky M. Maternal education and measures of early speech and language. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1999;42:1432–1443. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4206.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn LM. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–III (PPVT-III) Circle Pines, MN: AGS; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio B, Naremore RC, Connell PJ. Tracking children from poverty at risk for specific language impairment: A 3-year longitudinal study. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1996;39:611–624. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3903.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrity AW, Oetting JB. Auxiliary BE production by African American English-speaking children with and without specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2010 doi: 10.1044/1092–4388. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam WS, de Mesquita PB. The relationship between language and cognitive development and emotional-behavioral problems in financially-disadvantaged pre-schoolers: A longitudinal investigation. Early Child Development and Care. 2000;162:9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon P, Chafetz J. Verb-based versus class-based accounts of actionality effects in children’s comprehension of passives. Cognition. 1990;36:227–254. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(90)90058-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L. African American English: A linguistic introduction. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Guasti MT. Language acquisition: The growth of grammar. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Halle M, Marantz A. Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In: Hale K, Keyser SJ, editors. The view from building. Vol. 20. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1993. pp. 111–176. [Google Scholar]

- Hammill D, Newcomer P. Test of Language Development—Primary. 3. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Heath SB. Ways with words. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson V, de Villiers J. Syntactic frames in fast mapping verbs: Effect of age, dialect, and clinical status. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2009;52:610–622. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0135). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing S, Kamhi A. Alternative assessment of language and literacy in culturally and linguistically diverse populations. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2003;34:44–55. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2003/005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard LB, Deevy P, Miller CA, Rauf L, Charest M, Kurtz R. Surface forms and grammatical functions: Past tense and passive participle use by children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2003;46:43–55. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall CR, van der Lely HKJ. Derivational morphology in children with Grammatical-Specific Language Impairment. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics. 2007;42:71–91. doi: 10.1080/02699200600594491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting JB, Cantrell JP, Horohov JE. A study of specific language impairment (SLI) in the context of nonstandard dialect. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics. 1999;13:25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Oetting J, Cleveland LH, Cope R. Empirically derived combinations of tools and clinical cutoffs: An illustrative case with a sample of culturally/linguistically diverse children. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2008;39:44–53. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2008/005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting JB, Horohov JE. Past tense marking by children with and without specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1997;40:62–74. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4001.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting J, McDonald J. Nonmainstream dialect use and specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2001;44:207–223. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting J, McDonald J. Methods for characterizing participants’ nonmainstream dialect use within studies of child language. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2002;45:505–518. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/040). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting J, Newkirk B. Subject relative clause use by children with and without SLI across dialects. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics. 2008;22:111–125. doi: 10.1080/02699200701731414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña E, Iglesias A, Lidz C. Reducing test bias through dynamic assessment of children’s word learning ability. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2001;10:138–154. [Google Scholar]

- Peña E, Quinn R. Task familiarity: Effects on the test performance of Puerto Rican and African American children. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 1997;28:323–332. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461.2804.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt S, Oetting J. Past tense marking by African American English-speaking children reared in poverty. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2009;52:2–15. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0176). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi CH, Kaiser AP, Milan S, Hancock TB. Language performance of low-income African American and European American preschool children on the PPVT-III. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2006;37:1–12. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2006/002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk R, Greenbaum S, Leech G, Svartvik J. A comprehensive grammar of the English language. London, England: Longman; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Redmond SM. Children’s productions of the affix –ed in past tense and past participle contexts. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2003;46:1095–1109. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/086). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo MA, Schwanenflugel PJ, Blake J, Neuharth-Pritchett S, Cramer SE, Ruston HP. Performance on the PPVT–III and the EVT: Applicability of the measures with African American and European American preschool children. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2006;37:17–27. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2006/003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ML. Growth models of developmental language disorders. In: Rice ML, Warren SF, editors. Developmental language disorders: From phenotypes to etiologies. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 207–240. [Google Scholar]

- Rice ML. How different is disordered language? In: Colombo J, McCardle P, Freund P, editors. Infant pathways to language: Methods, models, and research directions. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Rice ML, Tomblin JB, Hoffman L, Richman WA, Marquis J. Grammatical tense deficits in children with SLI and nonspecific language impairment: Relationships with nonverbal IQ over time. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004;47:816–834. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/061). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ML, Wexler K. Toward tense as a clinical marker of specific language impairment in English-speaking children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1996;39:1239–1257. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3906.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ML, Wexler K, Cleave PL. Specific language impairment as a period of extended optional infinitive. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1995;38:850–863. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3804.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ML, Wexler K, Hershberger S. Tense over time: The longitudinal course of tense acquisition in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1998;41:1412–1431. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4106.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickford JR. African American vernacular English. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Roid G, Miller L. Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised (Leiter-R) Chicago, IL: Stoelting; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour H, Bland-Steward L, Green L. Difference versus deficit in child African American English. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 1998;29:96–108. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461.2902.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Lock KM. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Connecticut; Storrs: 1992. Morphological skills in normal and specifically language-impaired children. [Google Scholar]

- Tager-Flusberg H, Cooper J. Present and future possibilities for defining a phenotype for specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1999;41:900–912. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4205.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington JA, Craig HK. Dialectal forms during discourse of poor, urban, African American preschoolers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1994;37:816–823. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3704.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington JA, Craig HK. Performances of at-risk, African American preschoolers on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–III. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 1999;30:75–82. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461.3001.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst GJ. Language processes in context: Language learning in children reared in poverty. In: Adamson LB, Romski MA, editors. Communication and language acquisition: Discoveries from atypical development. Baltimore, MD: Brookes; 1997. pp. 233–265. [Google Scholar]