Abstract

Background

Ethanol and nicotine are often co-abused. However, their combined effects on fetal neural development, particularly on fetal neural stem cells (NSCs), which generate most neurons of the adult brain during the second trimester of pregnancy, are poorly understood. We previously showed that ethanol influenced NSC maturation in part, by suppressing expression of specific microRNAs (miRNAs). Here, we tested in fetal NSCs, the extent to which ethanol and nicotine co-regulated known ethanol-sensitive (miR-9, miR-21, miR-153 and miR-335), a nicotine-sensitive miRNA (miR-140-3p), and mRNAs for nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) subunits. Additionally, we tested the extent to which these effects were nAChR dependent.

Methods

Gestational day 12.5 mouse fetal murine cerebral cortical-derived neurosphere cultures were exposed to ethanol, nicotine and mecamylamine, a noncompetitive nAChR antagonist, individually or in combination, for short (24 hour) and long (five day) periods, to mimic exposure during the in vivo period of neurogenesis. Levels of miRNAs, miRNA-regulated transcripts and nAChR subunit mRNAs were assessed by qRT-PCR.

Results

Ethanol suppressed expression of known ethanol-sensitive miRNAs and miR-140-3p, while nicotine at concentrations attained by cigarette smokers, induced a dose-related increase in these miRNAs. Nicotine’s effect was blocked by ethanol and by mecamylamine. Finally, ethanol decreased expression of nAChR subunit mRNAs and, like mecamylamine, prevented the nicotine associated increase in α4 and β2 nAChR transcripts.

Conclusion

Ethanol and nicotine exert mutually antagonistic, nAChR-mediated effects on teratogen-sensitive miRNAs in fetal NSCs. These data suggest that concurrent exposure to ethanol and nicotine disrupts miRNA regulatory networks that are important for NSC maturation.

Keywords: Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, prenatal nicotine exposure, neural stem cells, miR-9, miR-21, miR-153, miR-335, miR-140-3p, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

Ethanol and nicotine are often used and abused concurrently. Moreover, a sizeable minority of women admit to smoking, and alcohol consumption during pregnancy (SAMHSA, 2009). There are well-documented links between maternal ethanol (Abel, 1984) as well as nicotine exposure (Winzer-Serhan, 2008), and fetal growth retardation and neurotoxicity. Between 2 to 5% of children born in the United States exhibit symptoms of fetal ethanol exposure (May et al., 2009), and postnatal development of a large percentage of these children may additionally be influenced by maternal nicotine exposure.

Though ethanol and nicotine are often co-abused, relatively little is known about their combined effects on fetal development, and specifically on molecular mechanisms that control fetal brain growth. Ethanol and nicotine appear to target common growth promoting pathways in fetal cortical neurons (Wang et al., 2007). Earlier reports indicate that both agents exhibit similar patterns of neurotoxicity in the developing cerebellum (Chen et al., 1998), though intriguingly, published reports also suggest that nicotine may, under a variety of circumstances, function like an antagonist to ethanol (Chen et al., 1999; Williams et al., 2009).

Most of the limited literature on the combined fetal effects of nicotine and ethanol has focused on assessing effects on differentiating neurons and on later periods of neonatal development. Virtually nothing is known about the combined effects of ethanol and nicotine on neural stem cell (NSC) populations that, during the second trimester-equivalent period of development (Bayer et al., 1993), produce most of the neurons of the adult brain. In an ex vivo model of fetal cerebral cortical NSCs and progenitor cells (NPCs), we showed that ethanol promoted aberrant proliferation and maturation of NSCs without inducing cell-death (Camarillo et al., 2007; Camarillo and Miranda, 2008; Prock and Miranda, 2007; Santillano et al., 2005). Moreover, ethanol’s effects were achieved in part, by the suppression of four microRNAs (miRNAs, (Sathyan et al., 2007)), members of a class of non-protein-coding regulatory RNAs that destabilize target mRNAs or repress their translation to dramatically alter cellular homeostasis and function. Because miRNAs are intimately associated with normal cellular processes, deregulation of miRNAs contributes to a vast array of human diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative and metabolic diseases (Ambros, 2004) and importantly, birth defects (Perera and Ray, 2007). Emerging research suggests that miRNAs also play significant roles in the pathogenesis of diseases associated with drugs of abuse (for review, see (Miranda et al., 2010)). Because of this possibility, we investigated whether nicotine could synergize with ethanol to regulate the expression of known ethanol-sensitive miRNAs, miR-9, miR-21, miR-153 and miR-335, in fetal stem cells, and whether ethanol in turn could regulate a known nicotine-sensitive miRNA (Huang and Li, 2009), miR140-3p. We also investigated the role of fetal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors nAChRs as mediators of ethanol and nicotine’s effects on miRNAs in fetal NSCs.

Experimental methods

Isolation of fetal mouse cerebral cortical neural precursors

All procedures were performed in accordance with institutional animal care committee guidelines and approval. Neural precursors were obtained from the dorsal telencephalic vesicle neuroepithelium (the structural precursor of the cerebral cortical projection neurons) of gestational day (GD) 12.5 C57BL/6 mouse fetuses according to previously published protocols (Camarillo et al., 2007; Prock and Miranda, 2007; Santillano et al., 2005; Sathyan et al., 2007). Care was taken to eliminate the surrounding meningeal tissue, as well as tissue precursors to the hippocampus and striatum. Precursor cultures were established at an initial density of 105 cells/ml in serum-free media (DMEM/F12 (catalog#11330-032; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR), 20 ng/ml bFGF (basic fibroblast growth factor; catalog #13256-029; Invitrogen), 20 ng/ml hEGF human epidermal growth factor; catalog #53003-018; Invitrogen), 0.15 ng/ml LIF (leukemia inhibitory factor; catalog #L200; Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel), ITS-X (insulin-transferrin-selenium-X) supplement (catalog #51500-056; Invitrogen), 0.85 Us/ml heparin (catalog #15077-019; Invitrogen), and 20 nM progesterone (catalog #P6149; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Neurosphere cultures are a well established ex vivo model that replicates the in vivo development and maturation of neuroepithelial NSCs/NPCs (Miranda et al., 2008; Ostenfeld and Svendsen, 2004).

Neurosphere culture treatment protocols

All experiments were performed with neurosphere cultures that were passaged no more than 3 times. GD12.5-derived mouse cortical neurosphere cultures were divided into aliquots containing ~1 million cells. Cultures were exposed to nicotine at 0, 0.1, 1, 10, 25, or 100 µM either alone, or with ethanol (320 mg/dl; 70 mM), for 5 days to approximate an in vivo exposure period corresponding to the second trimester-equivalent period of neurogenesis (Takahashi et al., 1999), and for some experiments, for one day to model immediate effects of nicotine and/or ethanol exposure. Some neurosphere cultures were also treated with the non-competitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) antagonist, Mecamylamine hydrochloride (1.0 uM, catalog #M9020 Sigma) either alone, in combination with nicotine, or with both nicotine and ethanol. The ethanol dose of 320 mg/dl (70 mM) was chosen to reflect levels that are well within ranges attainable by chronic alcoholics (Adachi et al., 1991) and also reflect levels actually attainable by a fetus after maternal exposure (Gottesfeld et al., 1990). We previously showed that this concentration of ethanol does not induce cell death in fetal NSCs, but rather, promotes stem cell maturation (Prock and Miranda, 2007; Santillano et al., 2005) and altered expression of developmental miRNAs (Sathyan et al., 2007). Ethanol concentrations in culture medium were verified by gas chromatography (Prock and Miranda, 2007). Nicotine at or less than 1uM brackets the EC50 for both nicotine activation and up-regulation of the α4β2 nicotinic receptor, the dominant brain nAChR isoform (Kuryatov et al., 2005), and can be attained by smokers (Russell et al., 1980; Williams et al., 2010). Doses above 1 uM and up to 100uM represent pharmacologic doses that have previously been used in research assessing the neural impact of nicotine (Falugi and Prestipino, 1989; Sallette et al., 2004) and saturate the α4β2 nAChR (Kuryatov et al., 2005), and can lead to nAChR desensitization.

Preparation of total RNA

Total RNA was extracted using the mirVana miRNA kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA yield and purity were evaluated with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies/Thermo Scientific). A260/A280 ratios between 1.96 and 2.04 were obtained for all samples of isolated RNA, confirming their high purity.

miRNA and mRNA qRT-PCR

(i) Real-time qRT-PCR for miRNAs was performed using the miRCURY LNA™ Universal RT miRNA PCR system (Exiqon, Denmark) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For each reverse transcription (RT) reaction 25 ng total RNA was used with first strand cDNA synthesis reaction kit (catalog # 203300; Exiqon, Denmark). The resulting cDNA was diluted 80X and 4 µl used in 10 µl PCR amplification reactions of three RT replicates per sample run on Applied Biosystems 7900HT real-time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the SYBR green-based real time PCR reaction kit (catalog #203450; Exiqon, Denmark) with specific miRNA primer sets (Table 1). U6 snRNA was used as a normalization control. After each PCR reaction, the specificity of the amplification was evaluated by a melt-curve analysis. Real-time RT-PCR data were quantified using the SDS 2.3 software package (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). (ii). Quantitative Real-Time-PCR was also performed for mRNAs for α3, α4, α7 and β2, β4 nAChRs subunits, and 18s RNA was used as a normalization control. Briefly, 100 ng of total RNA was converted into first-strand cDNA using qScript cDNA Supermix kit (catalog #95048-100; Quanta Biosciences, USA). Real-time PCR reactions were performed on a MyiQ single-color real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using the SYBR green-based real time PCR reaction kit (catalog #95053-500; PerfeCTa SYBR Green SuperMix for iQ, Quanta Biosciences, USA). Each reaction was performed with 4 µl of first-strand cDNA in a reaction volume of 20 µl. The specificity of the amplification was evaluated by a melt-curve analysis. For individual and reference gene primer sets (from Invitrogen, USA), see Table 2.

Table 1.

miRNA target sequences

| miRNA | Target Sequence | Sequence Reference |

|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-9 | UCUUUGGUUAUCUAGCUGUAUGA | MIMAT0000441 |

| hsa-miR-21 | UAGCUUAUCAGACUGAUGUUGA | MIMAT0000076 |

| hsa-miR-335 | UCAAGAGCAAUAACGAAAAAUGU | MIMAT0000765 |

| hsa-miR-153 | UUGCAUAGUCACAAAAGUGAUC | MIMAT0000439 |

| hsa-miR-140-3p | UACCACAGGGUAGAACCACGG | MIMAT0004597 |

Table 2.

mRNA Primer amplification pairs

| mRNA | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| α3 nAChR | 5’-GTGGAGTTCATGCGAGTCCCTG-3’ | 5’-TAAAGATGGCCGGAGGGATCC-3’ |

| α4 nAChR | 5’-AGCGGCTCCTGAAGAGACTC-3’ | 5’-ACACGTTGGTCGTCATCATC-3’ |

| α7 nAChR | 5’-TGTACTCGGGAGGGGCACCATG-3’ | 5’-TGTGCATGGCAAAGGCAAAGGCA-3’ |

| β2 nAChR | 5’-GTGGACGGTGTACGCTTCATTG-3’ | 5’-GGTCGTGGCAGTGTAGTTCTGG-3’ |

| β4 nAChR | 5’-AGATCTACAGGAGCATTAGAG-3’ | 5’-CTTGGAGGGTGCGTGGATCT-3’ |

| 18S | 5’-ATGGCCGTTCTTAGTTGGTG-3’ | 5’-CGCTGAGCCAGTCAGTGTAG-3’ |

Data Analysis and Statistics

Each data point derived from qRT-PCR assays represents an average of three technical replicates. Data (ΔCT) were averaged over independently replicated experiments (n=5 to 15 independently cultured samples) and expressed as the Mean fold-change over the mean of the control group (2^-ΔΔCT, (Sathyan et al., 2007)) ± SEM (Standard Error of the Mean). Data analysis was performed using SPSS (v18.0, IBM). Statistical outliers were defined as data points that exceeded three standard deviations from the mean of that group, when that data point was excluded from that group. No more than one data point was eliminated from any individual group and over the entire series of experiments, 0.006% of all data points were eliminated as outliers. Data were subjected a standard General Linear Models, Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA, Pillai’s Trace Statistic), followed by univariate Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Post-hoc, planned comparisons were then conducted using the Fisher’s Least Significance Difference (LSD) test. For all tests of group differences, α was set at < 0.05.

Results

1. Nicotine regulates the expression of Ethanol-sensitive miRNAs

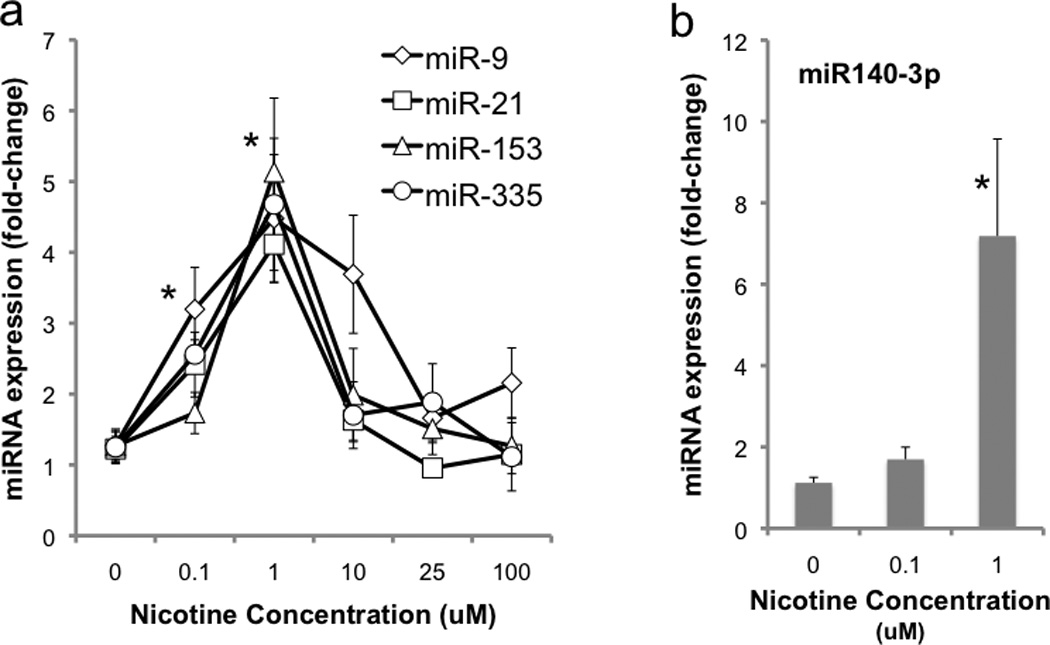

Mouse neurosphere cultures derived from GD12.5 mice were exposed to a dose range of nicotine for a period of 5 days. Multivariate analysis indicated that there was a statistically significant, ‘inverted U’-shaped dose response relationship between nicotine concentration and the expression of ethanol-sensitive miRNAs (Pillai’s Trace Statistic, F(20,152)=3.874, p<7.635E-7, Figure 1,a). Post-hoc ANOVAs for individual miRNAs also demonstrated a statistically significant relationship between nicotine concentration and miRNA expression (miR-9, F(5,38)=7.44, p<6.035E-5; miR-21, F(5,38)=8.6, p<1.614E-5; miR-153, F(5,38)=13.56, p<1.306E-7; miR-335, F(5,38)=10.84, p<1.578E-6). Importantly, doses of nicotine (0.1–1.0 uM), within a range attainable among cigarette smokers (Russell et al., 1980; Williams et al., 2010) resulted in increased expression of ethanol-sensitive miRNAs, whereas higher nicotine doses that can desensitize nAChRs (Buccafusco et al., 2009; Fenster et al., 1997; Quick and Lester, 2002; Wang and Sun, 2005) resulted in miRNA levels near control values. We also assessed the regulation of miR-140-3p, a miRNA which nicotine has been found to induce in rat PC12 cells ((Huang and Li, 2009), formerly termed miR-140*). We found that nicotine induced the expression of this miRNA in mouse fetal cortical-derived NSCs/NPCs as well (F(2,27)=12.35, p< 1.56E-4, Figure 1,b), specifically at 1uM (post-hoc LSD, p<3.67E-5), compared to controls.

Figure 1.

Dose-dependent effects of nicotine on the expression of (a) ethanol-sensitive miRNAs, miR-9, miR-21, miR-153 and miR-335 and (b) a previously identified nicotine-sensitive miRNA, miR-140-3p in GD12.5-derived mouse fetal cortical neuroepithelial precursors. Lower doses of nicotine, within the range attained by cigarette smokers, result in an increase in miRNA expression, whereas higher pharmacological concentrations of nicotine result in a suppression of miRNAs towards control levels. Data presented as mean (±SEM) fold-change relative to the mean of the control group (2^-ΔΔCT). Asterisks indicate statistically significant changes from controls (for details, see results section).

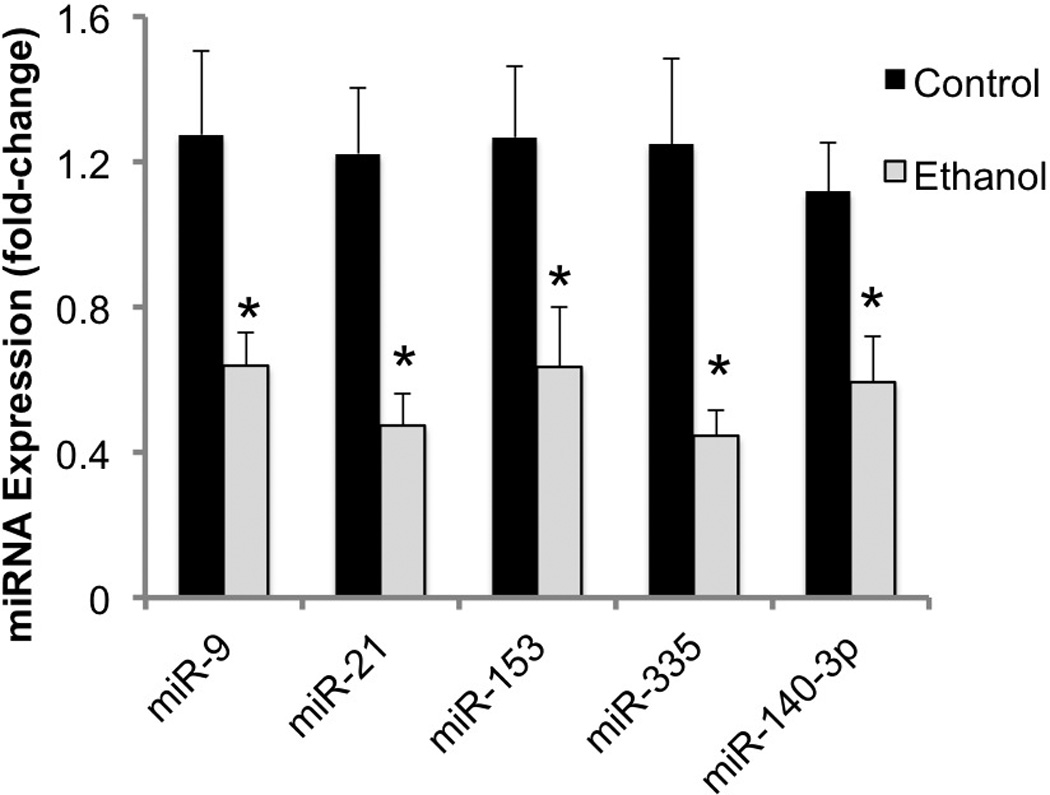

2. Ethanol suppresses the expression of both ethanol- and nicotine-sensitive miRNAs

We next tested whether ethanol at a dose attainable by alcoholic patients (Adachi et al., 1991)) would alter miRNA expression. As we reported earlier (Sathyan et al., 2007), ethanol at 320mg/dl induced significant 45–70% suppression in these miRNAs (i.e., miR-9 (t(21)=2.13, p<0.046), miR-21 (t(22)=3.053, p<0.006), miR-153 (t(23)=2.29, p<0.032) and miR-335 (t(23)=2.74, p<0.012)). Additionally, ethanol also suppressed the expression of the nicotine-sensitive miRNA, miR-140-3p (t(18)=2.12, p<0.048) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ethanol inhibits the expression of previously identified ethanol-sensitive and nicotine-sensitive miRNAs. Data presented as mean (±SEM) fold-change relative to the mean of the control group (2^-ΔΔCT). Asterisks indicate statistically significant changes from controls (for details, see results section).

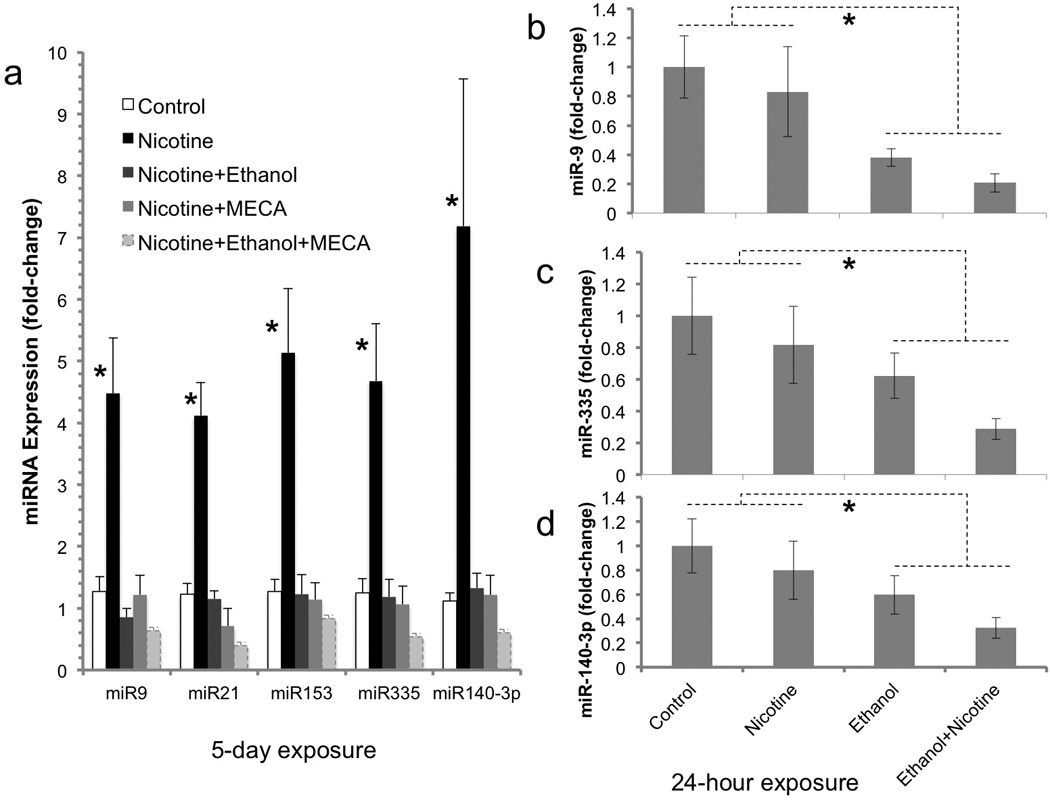

3. Ethanol and the nAChR antagonist mecamylamine antagonize the effect of nicotine on miRNA expression

Neurosphere cultures were initially exposed to nicotine alone or with ethanol and/or mecamylamine for five days to model exposure during the in vivo period of neurogenesis (Takahashi et al., 1999). Multivariate analysis (two-way MANOVA) indicated statistically significant interactions between the effects of nicotine and ethanol (Pillai’s Trace Statistic, F(5,37) = 5.9, p<4.185E-4), and between nicotine and mecamylamine exposure (Pillai’s Trace Statistic, F(5,37) = 13.07, p<2.344E-7). Therefore subsequent post-hoc univariate statistical analyses focused on further examination of interaction effects. Post-hoc 2-way ANOVA indicated statistically significant interaction effects of ethanol and nicotine for miR-9 (F(1,41) = 11.5, p<0.001), miR-21 (F(1,41) = 11.6, p<0.001), miR-153 (F(1,41) = 13.94, p<0.0005), miR-335 (F(1,41) = 11.31, p<0.001) and miR-140-3p (F(1,41) = 8.52, p<0.005). Similarly, there were statistically significant interaction effects between nicotine and mecamylamine for miR-9 (F(1,41) = 8.56, p< 0.005), miR-21 (F(1,41) = 25.01, p< 1.117E-5), miR-153 (F(1,41) = 28.46, p< 3.797E-6), miR-335 (F(1,41) = 30.35, p< 2.152E-6) and miR-140-3p (F(1,41) = 11.49, p<0.002). Overall, the data showed that both ethanol and mecamylamine, either alone or together, prevented the nicotine-induced increase in miRNA expression (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Regulation of miRNAs following long-term (5 day) and short-term (24 hour) ethanol/nicotine exposure. (a) Following five days exposure, ethanol and mecamylamine (MECA), individually and in combination, prevented the 1.0 uM nicotine-induced increase in miRNA expression. These data indicate that ethanol is functionally similar to MECA, a non-competitive nAChR antagonist, in terms of nAChR-mediated miRNA regulation. (b–d) Following short-term (24-hour) exposure, there was a main effect of ethanol on the expression of a sub-population of miRNAs. Ethanol alone, or in combination with nicotine, decreased the expression of miR-9 (b), miR-335 (c), and miR-140-3p (d). Data presented as mean (±SEM) fold-change relative to the mean of the control group (2^-ΔΔCT). Asterisks indicate statistically significant changes from controls (for details, see results section).

In a follow-up experiment, neurosphere cultures were exposed to nicotine or ethanol alone or in combination for 24 hours, to model a short-term exposure period. At this early time point, nicotine did not significantly increase the expression of any miRNA. However, there was a main effect of ethanol on miRNA expression. Exposure to ethanol, (either alone or in combination with nicotine) for 24 hours resulted in a decreased expression of miR-9 (F(1,16)=10.51, p<0.005, Figure 3b), miR-335 (F(1,16)=5.77, p<0.029, Figure 3c) and miR-140-3p (F(1,16)=5.5, p<0.032, Figure 3d). Other miRNAs were unaffected by nicotine and/or ethanol exposure for 24 hours. These data suggest that fetal neuroepithelial cells exhibit a delayed miRNA response to nicotine compared to ethanol.

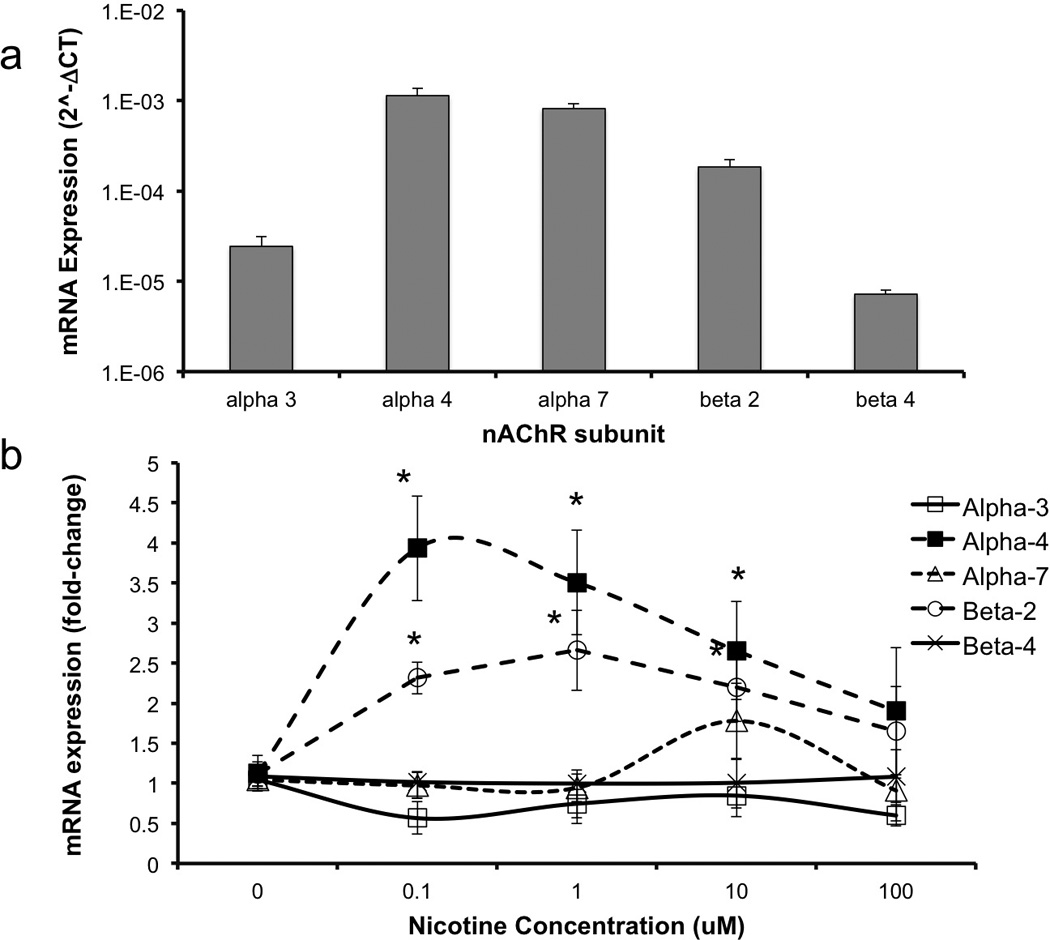

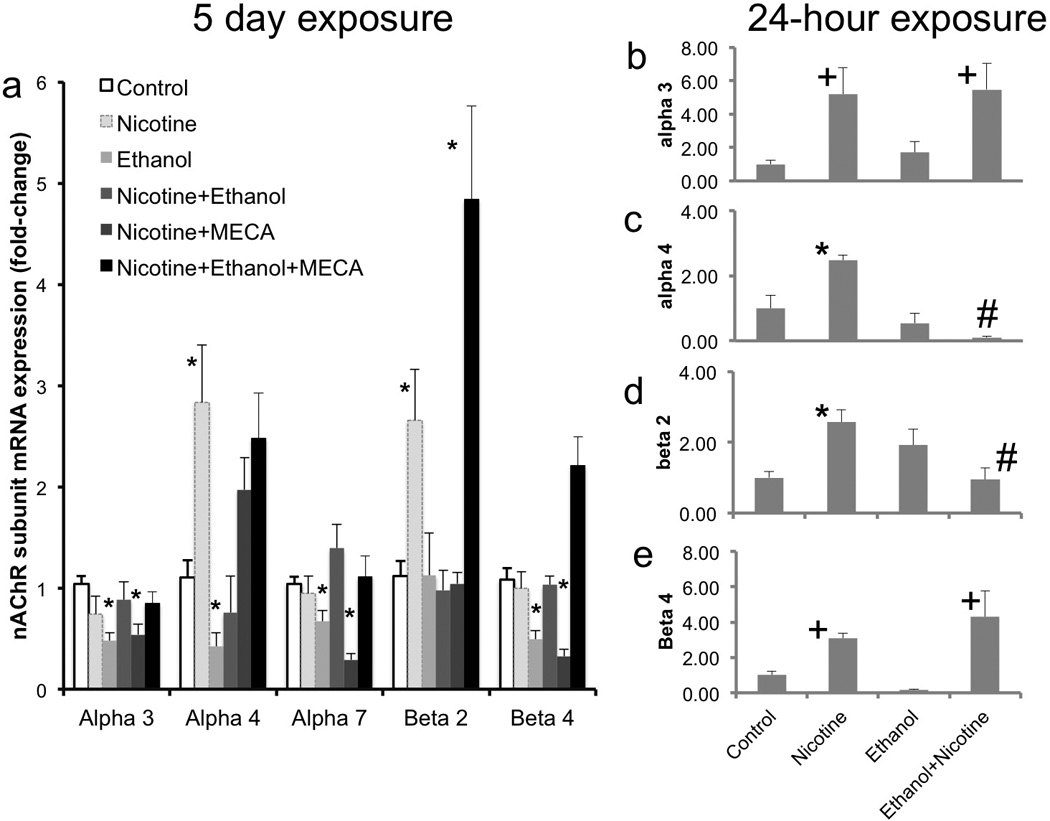

4. Effects of nicotine and ethanol on nAChR subunit mRNA transcripts

Previous reports (Broide et al., 1995; Zoli et al., 1995) showed that α3, α4, α7, β2 and β4 nAChR subunit mRNA transcripts are expressed in the fetal ventricular zone and therefore we assessed the expression levels of these transcripts in neurosphere cultures. Our data show that GD12.5 cerebral cortical neuroepithelium-derived neurosphere cultures express high levels of α4, α7 and β2 nAChR subunit mRNA transcripts compared to transcripts for α3 and β4 subunits (Figure 4,a). Multivariate analysis indicates that nicotine does regulate mRNA transcripts for nAChR subunits in fetal-derived neurosphere cultures (Pillai’s Trace Statistic, F(20,112)=3.7, p<4.83E-6). Post-hoc ANOVA indicated that nicotine induced a significant, dose-related increase in the α4 (F(4,29)=6.35, p<8.53E-4) and β2 (F(4,29)=8.18, p<1.52E-4) subunit mRNAs (Figure 4,b).

Figure 4.

(a) GD12.5 mouse neuroepithelial cells express α4, α7 and β2 nAChR subunit mRNA transcripts at higher levels compared to α3 and β4 transcripts. Data is expressed as mean (±SEM) of 2^-ΔCT relative to 18s RNA (b) Nicotine induced a statistically significant and dose-related increase in the expression of mRNA transcripts for α4 and β2 nAChR subunits. Data presented as mean (±SEM) fold-change relative to the mean of the control group (2^-ΔΔCT). Asterisks indicate statistically significant changes (for details, see results section).

We next tested whether ethanol influenced nAChR mRNA transcripts, and whether the effects of nicotine on nAChR mRNA transcripts could be blocked by either ethanol or non-competitive antagonist mecamylamine (MECA) alone, or in combination. In the first experiment, neurosphere cultures were treated with the above combination of reagents for five days to mimic exposure during the in vivo developmental period of neurogenesis (Takahashi et al., 1999). Overall, multivariate analysis showed a significant effect of treatment on nAChR subunit mRNAs (Pillai’s Trace Statistic, F(25,190)=5.9, p<1.45E-13, Figure 5a). Post-hoc ANOVA indicated a significant effect of treatment on α3 (F(5,38)=7.13, p<8.66E-5), α4 (F(5,38)=11.31, p<1.003E-6), α7 (F(5,38)=8.1, p<2.84E-5), β2 (F(5,38)=14.6, p<5.40E-8), and β4 (F(5,38)=13.5, p<1.51E-7). Post-hoc, planned comparison t-tests showed that ethanol significantly decreased every nAChR subunit (α3; p<3.07E-5, α4; p<0.036, α7; p<0.009, β4, p<0.001), except the β2 subunit. Both ethanol and mecamylamine individually prevented the nicotine induced increase in α4 and β2 subunit mRNA transcripts. However, in the presence of nicotine, the combination of ethanol and mecamylamine resulted in a significant and specific increase in the expression of the β2 and β4 subunits compared to either the non-exposed controls, nicotine or ethanol alone (all p values <0.03).

Figure 5.

(a) Following long-term exposure, Ethanol acted as an inverse agonist in suppressing the expression of α3, α4, α7 and β4 nAChR subunit mRNAs relative to controls. Both ethanol and MECA prevented the 1.0uM nicotine-induced increase in α4 and β2 nAChR mRNAs However, concurrent administration of ethanol and MECA resulted in the reappearance of the inductive effect of nicotine, specifically on β2 mRNA transcript levels, suggesting that ethanol’s effects on nAChR mRNA transcripts is contextual, and perhaps dependent on the activation state of nAChRs. (b–e) Short-term (24-hour) exposure to nicotine produced a significant increase in the mRNA expression for α3 (b), α4 (c), β2 (d), and β4 (e) nAChRs. Ethanol prevented the nicotine-mediated increase in the mRNAs for α4 and β2 nAChRs. Data presented as mean (±SEM) fold-change relative to the mean of the control group (2^-ΔΔCT). Asterisks indicate statistically significant changes relative to controls, ‘+’ indicates significant main effect of nicotine, and ‘#’ indicates significant effect of concurrent ethanol exposure, relative to nicotine alone (for details, see results section).

In a follow-up experiment, we assessed the effects of short-term (24-hour) exposure to ethanol and nicotine on nAChR mRNA subunit expression. We observed a main effect of nicotine, i.e., an increased expression of mRNA transcripts for the α3 (F(1,15)=10.32, p<0.006, Figure 5 b) and β4 (F(1,15)=6.89, p<0.019, Figure 5 e) subunits. In contrast, we observed a statistically significant interaction between 24-hour ethanol and nicotine exposure for the α4 (F(1,15)=13.96, p<0.002) and β2 (F(1,15)=14.73, p<0.002) mRNA subunits. While ethanol had no effect on the nicotine-induced increase in α3 and β4 mRNA subunits (Figure 5 b,e), it significantly prevented the inductive effect of nicotine on α-4 (p<3.95E-07) and β-2 (p<0.009) mRNA subunits (Figure 5 c,d). At 24 hours, neither ethanol (F(1,15)=0.007, ns) nor nicotine (F(1,15)=3.347, ns) significantly altered the expression of α7 mRNA.

Discussion

Ethanol and nicotine are often co-abused during pregnancy, and both produce persistent behavioral effects in exposed offspring. However, we know little about their coordinated contribution to fetal teratology. We focused on the second trimester of fetal development as a specific window of vulnerability to teratogens, because during this period NSCs proliferate rapidly to generate most of the neurons of the adult brain (Bayer et al., 1993). We reasoned that during this period of accelerated neurogenesis, relatively small teratogen-induced changes in the trajectory of stem cell maturation are likely to result is significant deficits in brain function. We (Camarillo and Miranda, 2008; Prock and Miranda, 2007; Santillano et al., 2005), and others (Kotkoskie and Norton, 1989; Miller, 1989; Miller, 1993; Miller, 1996; Mooney et al., 2004), previously showed that ethanol influences the proliferation and maturation of NSCs. More recently, we showed for the first time that some ethanol effects on NSCs were mediated by miRNA suppression (Sathyan et al., 2007). Here we show again in a new set of experiments that ethanol does indeed suppress the expression of the above miRNAs, validating our previously published data. Additionally, we find evidence that ethanol also suppresses a known nicotine-induced miRNA, miR-140-3p (previously termed miR-140*, (Huang and Li, 2009)), suggesting that ethanol also targets other teratogen-sensitive miRNAs.

Nicotine, like ethanol, leads to fetal growth retardation, and ethanol has previously been shown to influence brain function via nAChRs (Blomqvist et al., 1993). We therefore tested the hypothesis that nicotine potentiates the effect of ethanol on fetal stem cell miRNAs. Surprisingly, and contrary to our hypothesis, we report that in initial studies of prolonged (5-day) exposures, to mimic the length of the second trimester equivalent neurogenic period (Takahashi et al., 1999), nicotine antagonizes ethanol’s effects on miRNAs. Nicotine, at concentrations (0.1–1.0uM) attainable in the circulation of cigarette smokers (Russell et al., 1980; Williams et al., 2010), and bracketing the EC50 for nAChR activation (Kuryatov et al., 2005), significantly induced expression of all of the ethanol-suppressed miRNAs. Each of these miRNAs exhibited a more than 4-fold increase in expression in the presence of nicotine. Additionally, nicotine induced miR-140-3p expression in fetal cerebral cortical-derived NSCs/NPCs, consistent with its previously described effect in PC12 cells (Huang and Li, 2009). However, at pharmacological doses above 1 uM, a range utilized in several experimental reports (e.g.(Shoaib and Stolerman, 1999)), nicotine induced a dose-related decline in miRNA expression, perhaps because of nAChR desensitization or possibly, down-regulated receptor expression. We also found that shorter-term (24 hour) ethanol exposure resulted in significant suppression of a sub-population of sensitive miRNAs, miR-9, miR-335 and miR-140-3p, and this effect, in contrast to the effects of 5-day exposure, was not reversed by nicotine. These data show a temporal discordance between the effects of ethanol and nicotine, and that concurrent exposure may lead to initial suppression followed by later induction of critical fetal miRNAs. The impact of teratogen-driven temporal oscillations in miRNA levels on stem cell renewal and maturation need to be further investigated. Moreover, these initial studies do not capture the variability in nicotine and ethanol consumption patterns in human populations. Even long-term addicts, are likely to experience substantial daily, perhaps even hourly, variations in blood ethanol and nicotine concentration. The impact of variable drug exposure patterns on fetal miRNA expression also needs further investigation.

Fetal neuroepithelial nAChRs at least partly, link nicotine exposure to miRNA expression. Firstly, we observed that nAChR subunit mRNAs are expressed in NSCs/NPCs, consistent with their previously described expression within neuroepithelial cells of the fetal ventricular zone (Broide et al., 1995; Zoli et al., 1995). Moreover, prolonged (5-day) nicotine exposure itself specifically induced increased expression of α4 and β2 nAChR subunits, a finding that recapitulates earlier published reports (Lopez-Hernandez et al., 2004). Shorter-term (24-hour) nicotine exposure also transiently induced the expression of α3 and β4 mRNA subunits. These data suggest that neuroepithelial NSCs/NPCs continue to retain important aspects of their nAChR cellular identity. Secondly, the noncompetitive nAChR antagonist mecamylamine prevented the nicotine-induced increase in miRNA expression, further supporting a role for fetal nAChRs in miRNA regulation. The next step, i.e., the linkage between fetal nAChRs and miRNA regulation is unclear at this time. However activated nAChRs have been previously shown to induce transient calcium currents in fetal neuroepithelial cells (Atluri et al., 2001), which might be expected to engage a variety of intracellular signaling cascades. Moreover, recent research shows that a calcium-activated signaling pathway, mediated by Protein Kinase Cepsilon (PKCε), can increase cellular expression of at least one ethanol/nicotine sensitive miRNA, miR-21 (Bourguignon et al., 2009). Consequently, calcium-signaling pathways may be an important and uninvestigated mediator of both nicotine’s and ethanol’s effects on fetal miRNAs. Moreover, a predominant cohort of the ethanol-sensitive α4β2 nAChRs are intracellular, associated with the endoplasmic reticulum where nicotine alters endoplasmic reticulum function (Richards et al., 2011), in proximity to sites of miRNA action. Studies focused on the translation of α4 and β2 nAChR subunits, their assembly into heteromeric receptor complexes, their trafficking from the endoplasmic reticulum to the plasma membrane and integration into signaling networks will yield useful insights into the role of nAChRs in controlling NSC miRNAs.

Interestingly, following prolonged (5 days) exposure, ethanol decreased the mRNAs for all assessed nAChR subunits except the β2 subunit, behaving like an inverse agonist to nicotine for the α4 subunit. Ethanol also exhibited antagonist-like properties for α4 and β2 mRNA transcripts when co-administered with nicotine, similar the effect of the nicotinic antagonist mecamylamine. The mechanism of ethanol suppression of nAChR mRNA transcripts and antagonism of nicotinic effects is unclear at this time. However, ethanol suppression of nAChR mRNA transcripts in fetal NSCs is similar to the effect of ethanol observed previously in differentiated adult hippocampal neurons (Robles and Sabria, 2008), suggesting that mechanisms underlying ethanol regulation of nAChR mRNAs may be conserved through development, and from one brain region to another.

In silico analysis of nAChR 3’-UTRs using a variety of prediction algorithms (Targetscan, miRWalk, RNA22 and PICTAR5) indicates that none of the assessed nAChR subunit mRNAs contain canonical target recognition motifs for any ethanol or nicotine-sensitive miRNA. This finding suggests that ethanol and nicotine-regulated miRNAs do not activate auto-regulatory pathways to control the expression of nAChRs. In the absence of a readily apparent negative feedback loop, it is unlikely that the effects of a teratogen will be self-limiting. Rather the combination of our data and the results of in silico analyses indicate that nicotine/ethanol regulation of miRNAs is part of a feed-forward pathway that will amplify the fetal effects of teratogens. Such amplification may have important consequences for the function of miRNAs like miR-9, which plays an important role in specifying the midbrain-hindbrain boundary (Leucht et al., 2008) and in inhibiting the tumorigenic potential of NSCs (Schraivogel et al., 2011). Consequently, nicotine and ethanol regulation of miR-9 and other miRNAs is likely to have hitherto unsuspected consequences for fetal development that need further investigation.

In conclusion, we report here for the first time, that two commonly co-abused drugs, ethanol and nicotine, exert mutually antagonistic effects on teratogen-sensitive miRNAs in fetal NSCs. The effect of both nicotine and ethanol are mediated in part, by nAChRs, suggesting that fetal nAChRs play an important role in NSC maturation and the sensitivity of NSCs to alterations in the maternal-fetal environment. Moreover, at least one fetal ethanol-sensitive miRNA, miR-9, retains its ethanol sensitivity in the adult, where it has been shown to regulate another calcium-sensitive signaling component, the BK ion channel (Pietrzykowski et al., 2008), and differentiated neurons express additional ethanol-sensitive miRNAs (Guo et al., 2011). Therefore, it would be important to determine if ethanol and nicotine convergently, and perhaps via nAChRs, regulate miRNAs and their function in the adult brain as well, as a molecular component of addiction and withdrawal. It would be important to determine if the antagonistic relationship between nicotine and ethanol extended to specific mRNA targets as well. For example, we previously found that ethanol and ethanol-sensitive miRNAs targeted the mRNAs for the Notch ligand, Jag-1, and the brain-specific, differentiation-associated RNA binding protein, ELAVL2 (Sathyan et al., 2007). Ethanol and nicotine may coordinately control important miRNA-dependent mechanisms, to disrupt networks of protein-coding genes that are important for fetal NSC maturation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thanks Dr. Farida Sohrabji for reviewing this manuscript. This research was supported by a NIH grant, NIAAA R01AA013440, and by funds from Texas A&M Health Science Center to RCM.

References

- Abel EL. Prenatal effects of alcohol. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1984;14(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(84)90012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi J, Mizoi Y, Fukunaga T, et al. Degrees of alcohol intoxication in 117 hospitalized cases. J Stud Alcohol. 1991;52(5):448–453. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431(7006):350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atluri P, Fleck MW, Shen Q, et al. Functional nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression in stem and progenitor cells of the early embryonic mouse cerebral cortex. Dev Biol. 2001;240(1):143–156. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer S, Altman J, Russo R, Zhang X. Timetables of neurogenesis in the human brain based on experimentally determined patterns in the rat. Neuro Toxicology. 1993;14(1):83–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist O, Engel JA, Nissbrandt H, Soderpalm B. The mesolimbic dopamine-activating properties of ethanol are antagonized by mecamylamine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;249(2):207–213. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90434-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon LY, Spevak CC, Wong G, Xia W, Gilad E. Hyaluronan-CD44 interaction with protein kinase C(epsilon) promotes oncogenic signaling by the stem cell marker Nanog and the Production of microRNA-21, leading to down-regulation of the tumor suppressor protein PDCD4, anti-apoptosis, and chemotherapy resistance in breast tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(39):26533–26546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.027466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broide RS, O'Connor LT, Smith MA, Smith JA, Leslie FM. Developmental expression of alpha 7 neuronal nicotinic receptor messenger RNA in rat sensory cortex and thalamus. Neuroscience. 1995;67(1):83–94. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00623-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccafusco JJ, Beach JW, Terry AV., Jr Desensitization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as a strategy for drug development. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328(2):364–370. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.145292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camarillo C, Kumar LS, Bake S, Sohrabji F, Miranda RC. Ethanol regulates angiogenic cytokines during neural development: evidence from an in vitro model of mitogen-withdrawal-induced cerebral cortical neuroepithelial differentiation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(2):324–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camarillo C, Miranda RC. Ethanol exposure during neurogenesis induces persistent effects on neural maturation: evidence from an ex vivo model of fetal cerebral cortical neuroepithelial progenitor maturation. Gene Expr. 2008;14(3):159–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WJ, Parnell SE, West JR. Neonatal alcohol and nicotine exposure limits brain growth and depletes cerebellar Purkinje cells. Alcohol. 1998;15(1):33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(97)00084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WJ, Parnell SE, West JR. Effects of alcohol and nicotine on developing olfactory bulb: loss of mitral cells and alterations in neurotransmitter levels. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23(1):18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falugi C, Prestipino G. Localization of putative nicotinic cholinoreceptors in the early development of Paracentrotus lividus. Cell Mol Biol. 1989;35(2):147–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenster CP, Rains MF, Noerager B, Quick MW, Lester RA. Influence of subunit composition on desensitization of neuronal acetylcholine receptors at low concentrations of nicotine. J Neurosci. 1997;17(15):5747–5759. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05747.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesfeld Z, Morgan B, Perez-Polo JR. Prenatal alcohol exposure alters the development of sympathetic synaptic components and of nerve growth factor receptor expression selectivity in lymphoid organs. J Neurosci Res. 1990;26(3):308–316. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490260307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Chen Y, Carreon S, Qiang M. Chronic Intermittent Ethanol Exposure and Its Removal Induce a Different miRNA Expression Pattern in Primary Cortical Neuronal Cultures. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01689.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Li MD. Nicotine modulates expression of miR-140*, which targets the 3'-untranslated region of dynamin 1 gene (Dnm1) Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12(4):537–546. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotkoskie LA, Norton S. Morphometric analysis of developing rat cerebral cortex following acute prenatal ethanol exposure. 1989;106(3):283–288. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(89)90161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuryatov A, Luo J, Cooper J, Lindstrom J. Nicotine acts as a pharmacological chaperone to up-regulate human alpha4beta2 acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68(6):1839–1851. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.012419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht C, Stigloher C, Wizenmann A, et al. MicroRNA-9 directs late organizer activity of the midbrain-hindbrain boundary. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(6):641–648. doi: 10.1038/nn.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Hernandez GY, Sanchez-Padilla J, Ortiz-Acevedo A, et al. Nicotine-induced up-regulation and desensitization of alpha4beta2 neuronal nicotinic receptors depend on subunit ratio. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(36):38007–38015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403537200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP, Kalberg WO, et al. Prevalence and epidemiologic characteristics of FASD from various research methods with an emphasis on recent in-school studies. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15(3):176–192. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. Effects of prenatal exposure to ethanol on neocortical development: II. Cell proliferation in the ventricular and subventricular zones of the rat. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1989;287:326–338. doi: 10.1002/cne.902870305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Migration of cortical neurons is altered by gestational exposure to ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17(2):304–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Limited ethanol exposure selectively alters the proliferation of precursor cells in the cerebral cortex. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20(1):139–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda RC, Pietrzykowski AZ, Tang Y, et al. MicroRNAs: master regulators of ethanol abuse and toxicity? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(4):575–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda RC, Santillano DR, Camarillo C, Dohrman D. Modeling the impact of alcohol on cortical development in a dish: strategies from mapping neural stem cell fate. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;447:151–168. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-242-7_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney SM, Siegenthaler JA, Miller MW. Ethanol Induces Heterotopias in Organotypic Cultures of Rat Cerebral Cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14(10):1071–1080. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostenfeld T, Svendsen CN. Requirement for neurogenesis to proceed through the division of neuronal progenitors following differentiation of epidermal growth factor and fibroblast growth factor-2-responsive human neural stem cells. Stem Cells. 2004;22(5):798–811. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-5-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera RJ, Ray A. MicroRNAs in the search for understanding human diseases. BioDrugs. 2007;21(2):97–104. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200721020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzykowski AZ, Friesen RM, Martin GE, et al. Posttranscriptional regulation of BK channel splice variant stability by miR-9 underlies neuroadaptation to alcohol. Neuron. 2008;59(2):274–287. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prock TL, Miranda RC. Embryonic cerebral cortical progenitors are resistant to apoptosis, but increase expression of suicide receptor DISC-complex genes and suppress autophagy following ethanol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(4):694–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick MW, Lester RA. Desensitization of neuronal nicotinic receptors. J Neurobiol. 2002;53(4):457–478. doi: 10.1002/neu.10109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards CI, Srinivasan R, Xiao C, et al. Trafficking of alpha4* nicotinic receptors revealed by superecliptic phluorin: effects of a beta4 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated mutation and chronic exposure to nicotine. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(36):31241–31249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.256024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles N, Sabria J. Effects of moderate chronic ethanol consumption on hippocampal nicotinic receptors and associative learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;89(4):497–503. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell MA, Jarvis M, Iyer R, Feyerabend C. Relation of nicotine yield of cigarettes to blood nicotine concentrations in smokers. Br Med J. 1980;280(6219):972–976. doi: 10.1136/bmj.280.6219.972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallette J, Bohler S, Benoit P, et al. An extracellular protein microdomain controls up-regulation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by nicotine. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(18):18767–18775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2009. The NSDUH Report: Substance Use among Women During Pregnancy and Following Childbirth, vol NSDUH09-0521. [Google Scholar]

- Santillano DR, Kumar LS, Prock TL, et al. Ethanol induces cell-cycle activity and reduces stem cell diversity to alter both regenerative capacity and differentiation potential of cerebral cortical neuroepithelial precursors. BMC Neurosci. 2005;6:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-6-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathyan P, Golden HB, Miranda RC. Competing interactions between micro-RNAs determine neural progenitor survival and proliferation after ethanol exposure: evidence from an ex vivo model of the fetal cerebral cortical neuroepithelium. J Neurosci. 2007;27(32):8546–8557. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1269-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraivogel D, Weinmann L, Beier D, et al. CAMTA1 is a novel tumour suppressor regulated by miR-9/9(*) in glioblastoma stem cells. EMBO J. 2011 doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoaib M, Stolerman IP. Plasma nicotine and cotinine levels following intravenous nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;143(3):318–321. doi: 10.1007/s002130050954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Goto T, Miyama S, Nowakowski R, Caviness VJ. Sequence of neuron origin and neocortical laminar fate: relation to cell cycle of origin in the developing murine cerebral wall. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19(23):10357–10371. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10357.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Sun X. Desensitized nicotinic receptors in brain. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48(3):420–437. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Gutala R, Sun D, et al. Regulation of platelet-derived growth factor signaling pathway by ethanol, nicotine, or both in mouse cortical neurons. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(3):357–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM, Gandhi KK, Lu SE, et al. Higher nicotine levels in schizophrenia compared with controls after smoking a single cigarette. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(8):855–859. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SK, Cox ET, McMurray MS, et al. Simultaneous prenatal ethanol and nicotine exposure affect ethanol consumption, ethanol preference and oxytocin receptor binding in adolescent and adult rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2009;31(5):291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzer-Serhan UH. Long-term consequences of maternal smoking and developmental chronic nicotine exposure. Front Biosci. 2008;13:636–649. doi: 10.2741/2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoli M, Le Novere N, Hill JA, Jr, Changeux JP. Developmental regulation of nicotinic ACh receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat central and peripheral nervous systems. J Neurosci. 1995;15(3 Pt 1):1912–1939. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-01912.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]