Abstract

The current study examined the ability of cognitively normal young adults (n = 30) and older adults (n = 30) to perform a delayed match-to-sample task involving varying degrees of spatial interference to assess spatial pattern separation. Each trial consisted of a sample phase followed by a choice phase. During the sample phase, a circle appeared briefly on a computer screen. The participant was instructed to remember the location of the circle on the screen. During the choice phase, two circles were displayed simultaneously and the participant was asked to indicate which circle was in the same location as the sample phase circle. The two circles on choice phase trials were separated by one of four possible spatial separations: 0 cm, 0.5 cm, 1.0 cm, and 1.5 cm. Smaller separations are likely to create increased overlap among memory representations, which may result in heightened interference and a greater need for pattern separation. Consistent with this hypothesis, performance increased as a function of increased spatial separation in both young and older adults. However, young adults outperformed older adults, suggesting that spatial pattern separation may be less efficient in older adults due to potential age-related changes in the dentate gyrus and CA3 hippocampal subregions. Older adults also were divided into older impaired and older unimpaired groups based on their performance on a standardized test of verbal memory. The older impaired group was significantly impaired relative to both the older unimpaired and young groups, suggesting that pattern separation deficits may be variable in older adults. The present findings may have important implications for designing behavioral interventions for older adults that structure daily living tasks to reduce interference, thus improving memory function.

Keywords: Hippocampus, Dentate Gyrus, Aging, Spatial Memory, Interference

Introduction

Pattern separation is described as a mechanism for separating partially overlapping patterns of activation so that one pattern may be retrieved as separate from other patterns. The operation of a pattern separation mechanism is critical for reducing potential interference among similar memory representations and increasing the likelihood of accurate encoding and subsequent retrieval (Gilbert and Brushfield, 2009). Computational models have suggested that the hippocampus supports pattern separation (Marr, 1971; McNaughton and Nadel, 1989; O’Reilly and McClelland, 1994; Shapiro and Olton, 1994; Rolls and Kesner, 2006; Kesner, 2007; Myers and Scharfman, 2009; Rolls, 2010). Pattern separation may be a specific function of the dentate gyrus (DG) and its mossy fiber projections to the CA3 subregion of the hippocampus. Numerous studies have illustrated the critical role of the DG and CA3 in pattern separation in animal models using electrophysiological methods (McNaughton et al., 1989; Tanila, 1999; Leutgeb et al., 2004; 2005; 2007), neurotoxin induced lesions, (Gilbert et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2005; Gilbert and Kesner, 2006; Goodrich-Hunsaker et al., 2008; McTighe et al., 2009), and genetic manipulations (Kubik et al., 2007; McHugh et al., 2007).

To examine pattern separation in humans, Kirwan and Stark (2007) developed a paradigm to measure brain activity using high-resolution functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) while young, healthy human participants performed a continuous recognition task involving pictures of everyday objects. Some of the objects presented, referred to as lures, were very similar but not identical to previously presented objects. The lures were hypothesized to result in increased interference and an increased need for pattern separation based on overlapping object features. Activity in the hippocampus distinguished between correctly identified old stimuli, correctly rejected similar lure stimuli, and false alarms to similar lures. Another fMRI study from the same laboratory (Bakker et al., 2008) reported that when participants viewed these same stimuli, the results showed a consistent bias toward pattern separation in the DG and CA3 subregions. A recent study extended the findings from Bakker et al. (2008) by examining regional differences in brain activation while varying input similarity (Lacy et al., 2011). The data indicated that DG/CA3 subregion activity is sensitive to small changes in input, whereas the CA1 subregion activity is more resistant to small change. The results from these studies provide compelling evidence that the human hippocampus, and specifically DG and CA3 subregions, may play a critical role in pattern separation (also see reviews by Carr et al., 2010; Yassa and Stark, 2011b).

Aging has been shown to result in gray matter and white matter changes in a variety of brain regions (Allen et al., 2005; Ziegler et al., 2008; Driscoll et al., 2009; Kennedy and Raz, 2009). However, a primary region of the human brain affected by normal aging is the hippocampus (Good et al., 2001; Allen et al., 2005; Driscoll and Sutherland, 2005; Raz et al., 2005; Walhovd et al., 2010). Longitudinal studies have reported that the volumes of the hippocampal and parahippocampal cortices decrease in nondemented older adults (Driscoll et al., 2009). However, hippocampal volume has been reported to decrease at a faster rate than other medial temporal lobe structures such as the entorhinal cortex (Raz et al., 2004). In addition, longitudinal changes in hippocampal volume have been shown to be the primary determinant of memory decline (Mungas et al., 2005; Kramer et al., 2007). Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) signal intensity also has been shown to decline in all subregions of the hippocampus (DG, CA3, CA1) in older adults (Small et al., 2002). However, the DG subregion may be particularly susceptible to age-related changes in both humans (Small et al., 2002) and animal models (Small et al., 2004; Patrylo and Williamson, 2007). In addition to the degeneration specific to this region, cortical inputs from the entorhinal cortex to the dentate gyrus are significantly diminished (Geinisman et al., 1992), which subsequently impacts the feed forward connections to the CA3 subregion (Smith et al., 2000).

A model published by Wilson et al. (2006) suggests that age-related changes in the DG of the hippocampus may impair the ability to reduce similarity among new input patterns resulting in decreased efficiency in pattern separation. In addition, the model proposes that with advanced age, the CA3 subregion of the hippocampus may become entrenched in pattern completion, a mechanism that allows a complete representation of stored information to be retrieved using partial or degraded cues (Kesner and Hopkins, 2006). The model proposes that age-related changes in the hippocampus strengthen the autoassociative network of the CA3 subregion at the expense of processing new information and pattern separation. Similarly, a recent study by Yassa et al. (2011a) used high-resolution fMRI and ultrahigh-resolution diffusion imaging to show that reduced pattern separation activity in the DG/CA3 regions of aged humans was linked to structural changes in the perforant pathway. These changes were suggested to weaken the processing of novel information while strengthening the processing of stored information (Yassa et al., 2011a). Therefore, decreased efficiency in pattern separation may be a critical age-related processing deficit.

Given the well-documented role of the DG in supporting pattern separation, and the susceptibility of this region to age-related changes, recent studies have begun to examine age-related changes in pattern separation. Using the continuous recognition paradigm described previously (Kirwan and Stark, 2007), Toner et al. (2009) found that pattern separation for visual object information is impaired in older humans. A subsequent fMRI study supported these findings and additionally reported increased age-related activity in the DG and CA3 subregions when pattern separation demands were high (Yassa et al, 2010). Another recent study used a similar paradigm involving spatial stimuli (see Discussion section for details) and reported that a subset of older adults were biased toward pattern completion at a cost of efficient pattern separation (Stark et al., 2010). The findings of these studies are consistent with the models proposed by Wilson et al. (2006) and Yassa et al. (2011a). The present study sought to extend these findings by comparing the performance of cognitively normal young and older adults on a delayed match-to-sample for spatial location task involving varying degrees of spatial interference to assess spatial pattern separation.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The present study sample consisted of 30 cognitively normal older adults over 65 years of age (M = 74.5 yrs, SE = 1.23) and 30 young adults ranging in age from 18 – 25 years old (M = 20.1 yrs, SE = .41). All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at San Diego State University and the University of California at San Diego and all participants provided signed consent. All older adult participants underwent a near and far visual screening test prior to participation and all except two had corrected vision that fell between 20/20 and 20/40. The average years of education was 13.33 (SE .19) years for young adults and 14.5 (SE .44) for older adults. A one-way analysis of variance with age group (young adults, older adults) as the independent variable revealed a statistically significant difference in years of education completed, F(1, 58) = 5.98, p < .05. However, the mean difference in education level was only one year and the higher level of education was obtained in the older adult group.

Neuropsychological Measures

All participants completed a battery of standardized neuropsychological tests including the Trail Making and Color-Word Interference subscales from the Delis Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS; Delis et al., 2001), the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R; Benedict et al., 1998; Brandt and Benedict, 2001), the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised (BVMT-R; Benedict, 1997), and the Benton Judgment of Line Orientation Test (Benton et al., 1994). The older adults also were given the Dementia Rating Scale (DRS; Mattis, 1976) to assess general cognitive functioning and to screen for dementia. The average DRS score for older adults was 138.73 (SE .60) and any older adult participant who scored less than 130 was excluded from the study.

Spatial Pattern Separation Task

Participants completed a delayed match-to-sample for spatial location task modeled after a paradigm designed by Gilbert et al. (1998), involving varying degrees of spatial interference to assess spatial pattern separation. In the current study, the participant was seated approximately 40 cm in front of a computer monitor with a 15 cm black border affixed around the perimeter of the screen. The purpose of the border was to eliminate the possibility of using visual cues on the monitor to remember the spatial location of the stimuli. Each trial consisted of a sample phase followed by a choice phase. During the sample phase, a gray circle measuring 1.7 cm in diameter appeared on the computer screen for 5 s. The circle appeared in one of 18 possible locations within a fixed non-visible horizontal line across the middle of the screen. The participant was instructed in advance to remember the location of the circle on the screen. During the choice phase, two circles were displayed, one red and one blue. One of the colored circles (target) was in the same location as the original gray circle from the sample phase (correct choice). The foil circle was in a location that was either to the left or the right of the target circle (incorrect choice). There were four possible spatial separations that were used to separate the target and foil circles during the choice phase: 0 cm (edges of each circle were touching), 0.5 cm, 1.0 cm, and 1.5 cm. During the choice phase, the participant was asked to indicate which colored circle was in the same location as the gray circle from the sample phase by stating its color. During a 10 s delay between the sample phase and choice phase, participants were required to look away from the screen and read a string of random letters to prevent the participant from fixating the eyes on the location of the sample phase circle.

There were a total of 48 trials for the task, consisting of 12 trials for each of the four spatial separations. Each group of 12 trials was balanced across the entire width of the screen to ensure that there was not an unintentional bias toward one particular area on the screen. To minimize fatigue effects, the 48 trials were split into two sets of 24 trials. The two sets were identical in design. The order of each set of 24 trials was pseudo-randomized, with the restriction that there were no more than two consecutive trials of the following: (1) spatial separation, (2) correct circle on a particular side, or (3) correct circle of a particular color.

Results

The mean percent of correct responses for each of the spatial separations for young and older adults are presented in Figure 1. A 2 x 4 mixed model analysis of variance (ANOVA) with age group (young adults, older adults) as the between-participant factor and spatial separation (0 cm, 0.5 cm, 1.0 cm, and 1.5 cm) as the within-participant factor was used to analyze percent of correct responses. The analysis revealed a significant main effect of age group, F(1, 58) = 7.84, p < .01. On average, young adults outperformed older adults. There also was a significant main effect of spatial separation, F(3, 174) = 23.41, p < .001. Planned polynomial contrasts revealed a significant linear effect of spatial separation, F(1, 58) = 77.98, p < .001. On average, as the spatial separation increased, performance increased. However, the analysis did not detect a significant age group x spatial separation interaction F(3, 174) = .66, p = .58. The effect sizes for group differences at each spatial separation were calculated using Cohen’s d. The effect size was large for the 1.5 cm separtion (d = .892) and medium for the 1.0 cm separtion (d = .523), 0.5 cm separtion (d = .389), and 0 cm separtion (d = .295). To address the possibility that age-relalated differences on the spatial pattern separation task were due to a general memory deficit, HVLT delayed recall scores were entered into the model as a covariate. In this analysis, a significant main effect of group was retained, F(1, 57) = 4.11, p < .05. Also retained was a significant linear effect of spatial separation, F(1, 57) = 8.00, p < .01 and a trend for the main effect of spatial separation (p=.058). The mean (SE) performance on standardized neuropsychological measures for young adults and older adults are shown in Table 1. The DRS scores for all older adults were above 130. In addition, as indicated in the table, 87–90% of older adults performed in the normal range (based on age matched norms) on each measure, defined as less than1.5 standard deviations from the mean.

Figure 1.

Mean percent correct performance of young and older adults as a function of spatial separation on a spatial memory task.

Table 1.

Mean (SE) performance on standardized neuropsychology measures for young adults and older adults.

| Young Adults Mean (SE) | Older Adults Mean (SE) | |

|---|---|---|

| DRS | ||

| Total | N/A | 138.70 (.60) |

|

| ||

| HVLT-R | ||

| Total Immediate Recall | 26.70 (.76) | 24.77 (.95)a |

| Delayed Recall | 9.57 (.28) | 8.27 (.49)a |

| Retention Percentage | 92.66 (2.25) | 83.41 (3.84)b |

| Recognition | 11.17 (.19) | 10.03 (.29)b |

|

| ||

| BVMT-R | ||

| Total Immediate Recall | 29.70 (.97) | 20.90 (1.36)b |

| Learning | 4.00 (.49) | 3.87 (.38)a |

| Delayed Recall | 11.33 (.24) | 8.5 (.57)b |

| Retention Percentage | 97.53 (1.47) | 100.13 (5.34)a |

| Recognition | 5.83 (.07) | 5.33 (.21)a |

|

| ||

| D-KEFS Trail Making | ||

| Number-Letter Switching | 60.05 (4.74) | 115.37 (10.1)a |

|

| ||

| D-KEFS Color Word Interference | ||

| Inhibition | 46.33 (1.60) | 70.99 (3.56)a |

| Inhibition/Switching | 50.15 (1.40) | 78.35 (5.71)a |

|

| ||

| Benton Judgment of Line Orientation | ||

| Total Number Correct | 25.10 (.72) | 23.83 (.78)c |

≥ 90% of the older adults were in the normal range on this measure, defined as less than1.5 standard deviations from the mean

≥ 87% of the older adults were in the normal range on this measure, defined as less than1.5 standard deviations from the mean

≥ 87% of the older adults were in the normal range on this measure

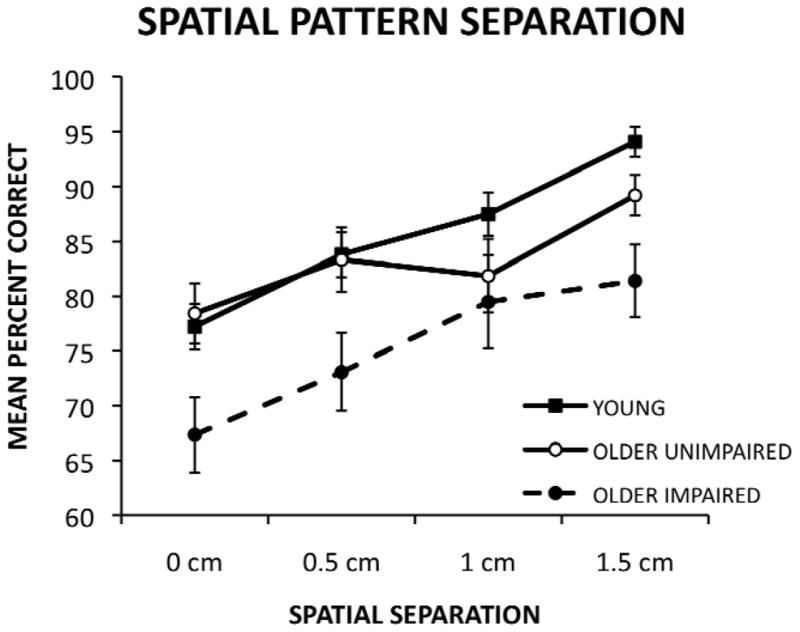

In an attempt to replicate the findings of a previous study (Stark et al., 2010) using a different spatial pattern separation task, the older adult group was divided into older impaired (OI) and older unimpaired (OU) based on their performance on the delayed word recall measure from the HVLT-R. Older unimpaired participants scored within the normal range for young adults (ages 20–29) on the delayed recall subtest of the HVLT-R (mean words recalled 10.18, SD 1.19), while OI participants scored more than 1 standard deviation below these norms (mean words recalled 5.77, SD 1.83). These two groups did not differ significantly in age, F(1, 28) = 2.00, ns. The mean percent of correct responses for each of the spatial separations for the OI, OU, and young groups are presented in Figure 2. A 3 × 4 ANOVA with group (young, OU, OI) as the between-participant factor and spatial separation (0 cm, 0.5 cm, 1.0 cm, and 1.5 cm) as the within-participant factor was conducted. As before, this analysis revealed a main effect of group, F(2, 57) = 8.16, p < .01; a main effect of spatial separation, F(3, 171) = 19.11, p < .001; and a linear effect of spatial separation, F(1, 57) = 63.38, p < .001. A Newman-Keuls posthoc comparison-test of the main effect of group revealed that the OI group was significantly impaired relative to the OU group (p < .05) and the young group (p < .05). However, there were no significant differences between the young and OU groups.

Figure 2.

Mean percent correct performance of young adults and older adults separated into older unimpaired and older impaired groups (based on the HVLT-R delayed recall measure) as a function of spatial separation on a spatial memory task.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to assess the ability of cognitively normal young and older adults to perform a spatial memory task involving varying degrees of spatial interference to assess spatial pattern separation. The results indicate that performance increased as a function of increased spatial separation in both young and older adults. It is hypothesized that as the spatial separation decreased (e.g. 0 cm and 0.5 cm separation trials), interference was likely to increase due to a high degree of overlap between the representations for the two choice phase circles. The ability to overcome this interference may have required the operation of a pattern separation mechanism to orthogonalize spatial input and create distinct representations. Since young adults outperformed older adults on the task, the data suggest that spatial pattern separation may become less efficient with increased age.

One could argue that the age-related deficits observed on the spatial pattern separation task may have been due to a general memory deficit rather than less efficient pattern separation. To statistically control for general memory ability, delayed recall scores from the HVLT-R were entered into the model as a covariate. The results from the ANCOVA demonstrated that the statistical findings from the original model maintained significance when the covariate was added, suggesting that general memory impairment alone does not account for the group differences in spatial pattern separation task performance. In addition, the significant linear effect demonstrates that performance increased as a function of increased spatial separation. It could be argued that a general memory impairment would result in comparable performance across spatial separations in older adults, which was not observed in the present data. Therefore, although general memory decline cannot be ruled out completely, we feel that the most parsimonious explanation of the present findings is that aging results in less efficient spatial pattern separation in older adults.

A recent study by Stark et al. (2010) also reported deficits in spatial pattern separation in a subset of older adults using a task with different mnemonic demands. Participants studied unique pairs of pictures and were later asked to identify whether the pictures were both in the same location as before or whether one of the pictures was in a different location. In the same condition, neither of the pictures in a pair was moved. In the three different conditions (close, medium, far) the location of one of the pictures in a pair was moved by varying both the distance and the angle from the original location. In the initial comparison of young and older adults, no differences were found in performance on the different trials. However, since the researchers were interested in the variability in memory impairment in aged individuals, the older adults were separated into an aged impaired group and aged unimpaired group, based on their performance on a standardized word learning task. Subsequent analyses revealed performance deficits on the close, medium, and far trials for the aged impaired group relative to both the aged unimpaired and young groups. The differences between young and older adults on the present study are very similar, both graphically and statistically, to the differences between aged impaired older adults and young adults in the study by Stark and colleagues (2010). Graphically, the largest group differences were observed in both studies on the largest separation trials, while the smallest group differences were found on the smallest separation trials. Statistically, both studies detected significant main effects of group and spatial separation, but not significant group x spatial separation interactions. The similarities between the two studies provide evidence these are robust findings. However, the current study offers a unique contribution to the literature because it demonstrates that, using the present task, it is possible to detect age-related differences in spatial pattern separation without separating normal older adults based on standardized test performance. It also is important to note that these findings were replicated using a unique spatial pattern separation paradigm. This paradigm examines the operation of a pattern separation mechanism by systematically manipulating the metric distance between two perceptually identical objects.

In an attempt to replicate the findings of the Stark and colleagues (2010) and investigate individual variability in pattern separation in older adults, performance on the current spatial pattern separation task was examined after dividing the older adults into impaired and unimpaired groups based on HVLT-R delayed recall performance. Our findings again are very similar to those of Stark and colleagues (2010), both statistically and graphically when the older adults are separated into older impaired and older unimpaired groups. The older impaired group was significantly impaired on the spatial pattern separation task, compared to both the older unimpaired group and the young adults, as evidenced by a significant main effect of group. Both studies also detected a significant main effect of spatial separation but not a group x separation interaction. In addition, the graphical depiction of performance in the two studies is very similar, with the largest group differences found at the largest spatial separation. The present findings, coupled with those from Stark and colleagues (2010), demonstrate that pattern separation efficiency may vary among older adults.

Since age-related differences in visuospatial perception could have contributed to the present findings, it is important to note that there were no significant differences between young adults and older adults on the Benton Judgment of Line Orientation task. In addition, all older adults except two tested with corrected vision within the normal range. The two participants who fell out of this range (20/70 and 20/100 vision) matched the performance of young adults on the spatial pattern separation task (i.e. were in the older unimpaired group). Collectively, these findings support the hypothesis that the impaired performance of older adults on the spatial pattern separation task was more related to deficient mnemonic processes, as opposed to impaired visuospatial perception.

As mentioned previously, there is substantial evidence that the process of pattern separation is facilitated by projections from the DG to the CA3 subregion of the hippocampus. The dentate gyrus is the region of the hippocampus that may be most adversely affected by age-related changes, in both humans (Small et al., 2002) and animals (Small et al., 2004). In addition, significant age-related changes have been documented in the perforant pathway in both humans (Yassa et al., 2011a) and animal models (Geinisman et al., 1992). This diminished input from the entorhinal cortex to the dentate gyrus also may impact the feed forward connections to the CA3 region of the hippocampus proper and this reduction in connectivity was shown to reliably predict spatial learning deficits in senescent rats (Smith et al., 2000). In addition, a fMRI study reported increased age-related activity in the DG and CA3 subregions when pattern separation demands were high (Yassa et al, 2010). Therefore in the current study, decreased efficiency in spatial pattern separation in older adults is likely a result of the age-related changes in the DG and CA3 subregion. Age-related memory decline has been reported to stem from subregion-specific epigenetic and transcriptional changes in the hippocampus (Penner et al., 2010). For example, neurogenesis has been shown to be reduced in aged animals (Kuhn et al., 1996) and may be related to impaired performance on hippocampal dependent tasks and decreased hippocampal volume (Driscoll et al., 2006). These newborn neurons may be involved in mnemonic processes particularly dependent on the DG subregion, such as pattern separation (Aimone et al., 2010; Clelland et al., 2009; Deng et al., 2010; Sahay et al., 2011). Therefore, behavioral tasks sensitive to age-related changes in pattern separation may have substantial implications for future studies of neurogenesis.

Evidence suggests that normal and pathological aging may have differential effects on the subregions of the hippocampus. As mentioned previously, the DG subregion may be particularly susceptible to age-related changes in humans; however, there may be less impact on pyramidal cells in the CA subregions (Small et al., 2002). In contrast, the CA subregions may be more vulnerable to pathological aging associated with AD (Braak and Braak, 1996; West et al., 2000; Price et al., 2001; Apostolova et al., 2010). A primary goal in Alzheimer’s disease research is to identify risk factors and preclinical markers of the disease. Given the differential impact of normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease on the various hippocampal subregions, tasks that are sensitive to dysfunction in particular subregions may help to differentiate between cognitive impairment associated with normal aging and pathological changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

In conclusion, the current study revealed that spatial pattern separation may become less efficient as a result of normal aging. The findings add to a relatively small but growing literature reporting decreased pattern separation efficiency in nondemented older adults on tasks involving visual objects (Toner et al., 2009; Yassa et al., 2010; Yassa et al., 2011a) and spatial stimuli (Stark et al., 2010). These findings may have important implications for designing behavioral interventions for older adults that structure daily living tasks to reduce interference, thus improving memory function. In addition, recent studies have begun to examine the relationship between standardized memory test performance and specific hippocampal subregion function (Brickman et al., 2010). Behavioral tasks that measure specific mnemonic processes, such as the one employed in the current study, may be highly sensitive to subtle age-related changes. These tests may be used one day in conjunction with standardized neuropsychological measures to differentiate normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a National Institutes of Health Grant (#AG034202) from the National Institute on Aging awarded to Paul E. Gilbert. We thank Ryan Cardinale, Misty Brewer, Jacquelyn Szajer, Enrique Gracian, and Laura Shelley for their assistance with data collection. We also thank all of the participants for their contributions to this study.

References

- Aimone JB, Deng W, Gage FH. Adult neurogenesis: Integrating theories and separating functions. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010;14:325–337. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JS, Bruss J, Brown CK, Damasio H. Normal neuroanatomical variation due to age: The major lobes and a parcellation of the temporal region. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:1245–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolova LG, Hwang KS, Andrawis JP, Green AE, Babakchanian S, Morra JH, Cummings JL, Toga AW, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Jack CR, Jr, Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Jagust WJ, Koeppe RA, Mathis CA, Weiner MW, Thompson PM Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. 3D PIB and CSF biomarker associations with hippocampal atrophy in ADNI subjects. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:1284–1303. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A, Kirwan CB, Miller M, Stark CE. Pattern separation in the human hippocampal CA3 and dentate gyrus. Science. 2008;319:1640–1642. doi: 10.1126/science.1152882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict RHB. The brief visuospatial memory test – revised: Professional manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict RHB, Schretlen D, Groninger L, Brandt J. The Hopkins verbal learning test –revised: Normative data and analysis of inter-form and test-retest reliability. Clin Neuropsychol. 1998;12:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Benton A, Sivan A, Hamsher K, Varney N, Spreen O. Contributions to neuropsychological assessment: A clinical manual. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Development of Alzheimer-related neurofibrillary changes in the neocortex inversely recapitulates cortical myelogenesis. Acta Neuropathol. 1996;92:197–201. doi: 10.1007/s004010050508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J, Benedict RHB. Professional manual. Lutz: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2001. Hopkins verbal learning test-revised. [Google Scholar]

- Brickman AM, Stern Y, Small SA. Hippocampal subregions differentially associate with standardized memory tests. Hippocampus. 2010 doi: 10.1002/hipo.20840. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr VA, Rissman J, Wagner AD. Imaging the human medial temporal lobe with high-resolution fMRI. Neuron. 2010;65:298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clelland CD, Choi M, Romberg C, Clemenson GD, Jr, Fragniere A, Tyers P, Jessberger S, Saksida LM, Barker RA, Gage FH, Bussey TJ. A functional role for adult hippocampal neurogenesis in spatial pattern separation. Science. 2009;325:210–213. doi: 10.1126/science.1173215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis D, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. Delis-Kaplan executive function system (D-KEFS) San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Deng W, Aimone JB, Gage FH. New neurons and new memories: How does adult hippocampal neurogenesis affect learning and memory? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:339–350. doi: 10.1038/nrn2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll I, Sutherland RJ. The aging hippocampus: Navigating between rat and human experiments. Rev Neurosci. 2005;16:87–121. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2005.16.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll I, Howard SR, Monfils MH, Tomanek B, Brooks WM, Sutherland RJ. The aging hippocampus: A multi-level analysis in the rat. Neuroscience. 2006;139:1173–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll I, Davatzikos C, An Y, Wu X, Shen D, Kraut M, Resnick SM. Longitudinal pattern of regional brain volume change differentiates normal aging from MCI. Neurology. 2009;72:1906–1913. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a82634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geinisman Y, deToledo-Morrell L, Morrell F, Persina IS, Rossi M. Age-related loss of axospinous synapses formed by two afferent systems in the rat dentate gyrus as revealed by the unbiased stereological dissector technique. Hippocampus. 1992;2:437–444. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450020411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PE, Kesner RP, DeCoteau WE. Memory for spatial location: Role of the hippocampus in mediating spatial pattern separation. J Neurosci. 1998;18:804–810. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-02-00804.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PE, Kesner RP, Lee I. Dissociating hippocampal subregions: Double dissociation between dentate gyrus and CA1. Hippocampus. 2001;11:626–636. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PE, Kesner RP. The role of the dorsal CA3 hippocampal subregion in spatial working memory and pattern separation. Behav Brain Res. 2006;169:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PE, Brushfield AM. The role of the CA3 hippocampal subregion in spatial memory: A process oriented behavioral assessment. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33:774–781. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good CD, Johnsrude IS, Ashburner J, Henson RN, Friston KJ, Frackowiak RS. A voxel-based morphometric study of ageing in 465 normal adult human brains. Neuroimage. 2001;14:21–36. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich-Hunsaker NJ, Hunsaker MR, Kesner RP. The interactions and dissociations of the dorsal hippocampus subregions: How the dentate gyrus, CA3, and CA1 process spatial information. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122:16–26. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy KM, Raz N. Aging white matter and cognition: Differential effects of regional variations in diffusion properties on memory, executive functions, and speed. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:916–927. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP. A behavioral analysis of dentate gyrus function. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:567–576. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP, Hopkins RO. Mnemonic functions of the hippocampus: A comparison between animals and humans. Biol Psychol. 2006;73:3–18. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan CB, Stark CE. Overcoming interference: An fMRI investigation of pattern separation in the medial temporal lobe. Learn Mem. 2007;14:625–633. doi: 10.1101/lm.663507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JH, Mungas D, Reed BR, Wetzel ME, Burnett MM, Miller BL, Weiner MW, Chui HC. Longitudinal MRI and cognitive change in healthy elderly. Neuropsychology. 2007;21:412–418. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.21.4.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubik S, Miyashita T, Guzowski JF. Using immediate-early genes to map hippocampal subregional functions. Learn Mem. 2007;14:758–770. doi: 10.1101/lm.698107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn HG, Dickinson-Anson H, Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat: Age-related decrease of neuronal progenitor proliferation. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2027–2033. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-02027.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy JW, Yassa MA, Stark SM, Muftuler LT, Stark CE. Distinct pattern separation related transfer functions in human CA3/dentate and CA1 revealed using high-resolution fMRI and variable mnemonic similarity. Learn Mem. 2011;18:15–18. doi: 10.1101/lm.1971111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Jerman TS, Kesner RP. Disruption of delayed memory for a sequence of spatial locations following CA1- or CA3-lesions of the dorsal hippocampus. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2005;84:138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb S, Leutgeb JK, Treves A, Moser MB, Moser EI. Distinct ensemble codes in hippocampal areas CA3 and CA1. Science. 2004;305:1245–1246. doi: 10.1126/science.1100265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb S, Leutgeb JK, Barnes CA, Moser EI, McNaughton BL, Moser MB. Independent codes for spatial and episodic memory in hippocampal neuronal ensembles. Science. 2005;309:568–569. doi: 10.1126/science.1114037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb JK, Leutgeb S, Moser MB, Moser EI. Pattern separation in the dentate gyrus and CA3 of the hippocampus. Science. 2007;315:961–966. doi: 10.1126/science.1135801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr D. Simple memory: A theory for archicortex. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1971;262:23–81. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1971.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattis S. Mental status examination for organic mental syndrome in the elderly patient. In: Bellack L, Katsau TB, editors. Geriatric psychiatry: A handbook for psychiatrists and primary care physicians. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1976. pp. 77–121. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh TJ, Jones MW, Quinn JJ, Balthasar N, Coppari R, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB, Fanselow MS, Wilson MA, Tonegawa S. Dentate gyrus NMDA receptors mediate rapid pattern separation in the hippocampal network. Science. 2007;317:94–99. doi: 10.1126/science.1140263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton BL, Barnes CA, Meltzer J, Sutherland RJ. Hippocampal granule cells are necessary for normal spatial learning but not for spatially-selective pyramidal cell discharge. Exp Brain Res. 1989;76:485–496. doi: 10.1007/BF00248904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton BL, Nadel L. Hebb-Marr networks and the neurobiological representation of action in space. In: Gluck MA, Rumelhart DE, editors. Neuroscience and connectionist theory. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1990. pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- McTighe SM, Mar AC, Romberg C, Bussey TJ, Saksida LM. A new touchscreen test of pattern separation: effect of hippocampal lesions. Neuroreport. 2009;20:881–885. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32832c5eb2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungas D, Harvey D, Reed BR, Jagust WJ, DeCarli C, Beckett L, Mack WJ, Kramer JH, Weiner MW, Schuff N, Chui HC. Longitudinal volumetric MRI change and rate of cognitive decline. Neurology. 2005;65:565–571. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172913.88973.0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers CE, Scharfman HE. A role for hilar cells in pattern separation in the dentate gyrus: A computational approach. Hippocampus. 2009;19:321–337. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly RC, McClelland JL. Hippocampal conjunctive encoding, storage, and recall: Avoiding a trade-off. Hippocampus. 1994;4:661–682. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450040605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrylo PR, Williamson A. The effects of aging on dentate circuitry and function. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:679–696. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner MR, Roth TI, Chawla MK, Hoang LT, Roth ED, Lubin FD, Sweatt JD, Worley PF, Barnes CA. Age related changes in Arc transcription and DNA methylation within the hippocampus. Neurobiol Aging. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.01.009. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JL, Ko AI, Wade MJ, Tsou SK, McKeel DW, Morris JC. Neuron number in the entorhinal cortex and CA1 in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1395–1402. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.9.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N, Gunning-Dixon F, Head D, Rodrigue KM, Williamson A, Acker JD. Aging, sexual dimorphism, and hemispheric asymmetry of the cerebral cortex: Replicability of regional differences in volume. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:377–396. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N, Lindenberger U, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Head D, Williamson A, Dahle C, Gerstorf D, Acker JD. Regional brain changes in aging healthy adults: General trends, individual differences and modifiers. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:1676–1689. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET. A computational theory of episodic memory formation in the hippocampus. Behav Brain Res. 2010;215:180–196. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET, Kesner RP. A computational theory of hippocampal function, and empirical tests of the theory. Prog Neurobiol. 2006;79:1–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha A, Wilson DA, Hen R. Pattern separation: A common function for new neurons in hippocampus and olfactory bulb. Neuron. 2011;70:582–588. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro ML, Olton DS. Hippocampal function and interference. In: Schacter DL, Tulving E, editors. Memory systems. London: MIT; 1994. pp. 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Small SA, Tsai WY, DeLaPaz R, Mayeux R, Stern Y. Imaging hippocampal function across the human life span: is memory decline normal or not? Ann Neurol. 2002;51:290–295. doi: 10.1002/ana.10105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small SA, Chawla MK, Buonocore M, Rapp PR, Barnes CA. Imaging correlates of brain function in monkeys and rats isolates a hippocampal subregion differentially vulnerable to aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7181–7186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400285101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TD, Adams MM, Gallagher M, Morrison JH, Rapp PR. Circuit-specific alterations in hippocampal synaptophysin immunoreactivity predict spatial learning impairment in aged rats. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6587–6593. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06587.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark SM, Yassa MA, Stark CE. Individual differences in spatial pattern separation performance associated with healthy aging in humans. Learn Mem. 2010;17:284–288. doi: 10.1101/lm.1768110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanila H. Hippocampal place cells can develop distinct representations of two visually identical environments. Hippocampus. 1999;9:235–246. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1999)9:3<235::AID-HIPO4>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toner CK, Pirogovsky E, Kirwan CB, Gilbert PE. Visual object pattern separation deficits in nondemented older adults. Learn Mem. 2009;16:338–342. doi: 10.1101/lm.1315109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walhovd KB, Fjell AM, Dale AM, McEvoy LK, Brewer J, Karow DS, Salmon DP, Fennema-Notestine C Alzheimer’s Disease Neuorimaging Initiative. Multi-modal imaging predicts memory performances in normal aging and cognitive decline. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:1107–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ, Coleman PD, Flood DG, Troncoso JC. Differences in the pattern of hippocampal neuronal loss in normal ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 1994;344:769–772. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92338-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ, Kawas CH, Martin LJ, Troncoso JC. The CA1 region of the human hippocampus is a hot spot in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;908:255–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson IA, Gallagher M, Eichenbaum H, Tanila H. Neurocognitive Aging: Prior memories hinder new hippocampal encoding. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:662–670. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassa MA, Lacy JW, Stark SM, Albert MS, Gallagher M, Stark CE. Pattern separation deficits associated with increased hippocampal CA3 and dentate gyrus activity in nondemented older adults. Hippocampus. 2010 doi: 10.1002/hipo.20808. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassa MA, Mattfeld AT, Stark SM, Stark CE. Age-related memory deficits linked to circuit-specific disruptions in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011a;108:8873–8878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101567108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassa MA, Stark CE. Pattern separation in the hippocampus. Trends Neurosci. 2011b;34:515–525. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler DA, Piguet O, Salat DH, Prince K, Connally E, Corkin S. Cognition in healthy aging is related to regional white matter integrity, but not cortical thickness. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;31:1912–1926. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]