Abstract

OTHER THEMES PUBLISHED IN THIS IMMUNOLOGY IN THE CLINIC REVIEW SERIES

Metabolic diseases, host responses, cancer, autoinflammatory diseases, allergy.

Convincing evidence now indicates that viruses are associated with type 1 diabetes (T1D) development and progression. Human enteroviruses (HEV) have emerged as prime suspects, based on detection frequencies around clinical onset in patients and their ability to rapidly hyperglycaemia trigger in the non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse. Whether or not HEV can truly cause islet autoimmunity or, rather, act by accelerating ongoing insulitis remains a matter of debate. In view of the disease's globally rising incidence it is hypothesized that improved hygiene standards may reduce the immune system's ability to appropriately respond to viral infections. Arguments in favour of and against viral infections as major aetiological factors in T1D will be discussed in conjunction with potential pathological scenarios. More profound insights into the intricate relationship between viruses and their autoimmunity-prone host may lead ultimately to opportunities for early intervention through immune modulation or vaccination.

Keywords: autoimmunity, beta cells, hygiene, type 1 diabetes, viruses

Introduction

Viruses, especially human enteroviruses (HEV), have long been suspected as environmental agents that can instigate type 1 diabetes (T1D) onset in humans [1]–[3]. The extreme difficulty in biopsying pancreas has made it almost impossible to assay for viruses (or any other pathogen) in the pancreas at the time of T1D onset, a scientifically sound type of observation for associating specific pathogens with a disease. Associations of viruses other than HEV with a T1D aetiology (e.g. rubella virus [4]) or in mouse models (e.g. [5],[6]), as well as diverse reports of involvement of different HEV in T1D onset (reviewed in [1],[7]), continues to fuel debate as to either a specific role for diverse viruses in T1D onset or a role for specific viruses themselves. Further confounding the issue are data from the non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse model showing that HEV can, in fact, induce long-term protection from the onset of host-driven autoimmune T1D onset [1],[8],[9] and the oft-repeated criticism of the inadequacy of the NOD mouse model itself [10].

Still other related factors fit into this complex picture. The question of hygiene and its role in reducing contact with faecal–oral transmitted microbes and viruses has beenargued to be of potential importance when considering how human T1D comes about [1],[11]. Are other viruses that have yet to be associated with T1D involved in the disease? A human cardiovirus (Saffold virus) is widespread among humans [12], but whether it has an impact on T1D is completely unknown. However, what makes this an interesting question is the demonstration that another well-studied cardiovirus encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) has long been used as a model for studying T1D in mice. Are viruses involved in a T1D aetiology through rapid exposure (so-called ‘hit-and-run’), presumably by damaging beta cells [13], or is persistence of virus involved, suggesting a long-term (cell damage and immunological) impact upon the host? Until recently, the persistence of HEV in the host was poorly understood, but we now know that HEV can and do persist in both naturally infected humans as well as in experimental systems [14]–[16]. Might persistent viral populations play a role in human T1D?

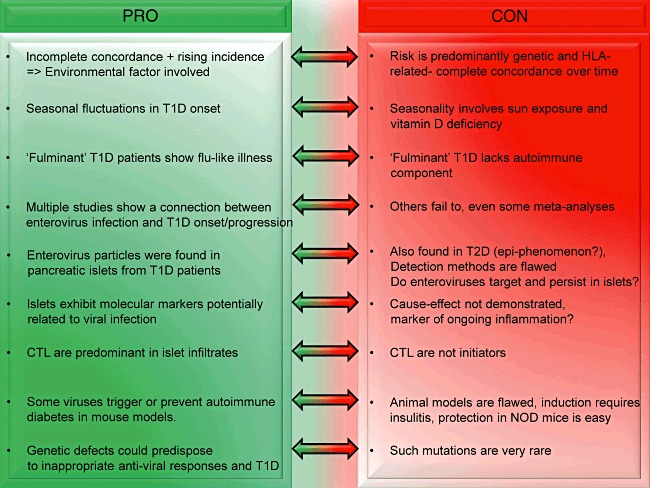

Here we will review briefly how we have thought about these issues in a point–counterpoint type of approach, in the hope that the discussion may stimulate new thinking and prompt new approaches towards deciphering the aetiology of human T1D (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Point–counterpoint argument for a viral aetiology in type 1 diabetes (T1D).

Arguments in favour of viral involvement in the pathogenesis of T1D

Rising T1D incidence: a matter of hygiene?

Environmental events should be factored in

In analogy with many other autoimmune diseases, a strong genetic component exists in T1D [17], located mainly within the human leucocyte antigen (HLA) region [18]–[20]. Despite the apparent importance of inherited susceptibility in the development of T1D, genetics alone cannot account for the disease's entire aetiological spectrum. One of the most important indications is the rapid increase in T1D incidence since the 1950s, particularly within the age group younger than 5 years [21]–[24]: a too-rapid growth to be explained reasonably by genetic changes. In addition, twin studies have identified concordance rates that do not exceed 40% [25]. Such arguments lend support to the notion that one, or perhaps multiple, environmental event(s) should be factored in to explain disease development, and particularly the onset of clinical hyperglycaemia in predisposed individuals.

The concept of hygiene

Humans – like all other organisms on the planet – respond to environmental influences. Until somewhat recently, humans had only a dim notion of, and so generally neglected, the concept of hygiene. Consequently, exposure to faecal–oral transmitted microorganisms and viruses was high from birth onwards. One disease that is spread by a faecal–oral-transmitted HEV and which was rare in our collective past, but became horrifically important to human health in the 20th century, is poliovirus (PV)-induced poliomyelitis. It is of interest that T1D, also rare in the past but common today, has also been linked closely to HEV infections (reviewed in [26]; recent meta-analysis in [27]). In the case of PV, immunity acquired by a combination of passive immune transfer through nursing and environmental exposure to infectious PV resulted in poliomyelitis being rarely manifested. Could a similar effect with other viruses, such as species B HEV [1], have resulted in maintaining T1D at a low level in our human past? Experimental data showing that autoimmune T1D is suppressed in NOD mice following inoculation with HEV [8] and that such exposure can promote expansion of a protective regulatory T cell (Treg) population [28] support this hypothesis. In a modern society, in which common exposure to faecal pathogens such as HEV has been greatly minimized, failure to become immune to one or more specific HEV by a certain age leaves one open to an HEV infection and a potentially aggressive attack on the pancreas, which may lead in turn to T1D onset [1]. Observational data of T1D incidence indifferent countries and societies [29] generally support the concept that more rural and/or less developed populations have a lower T1D risk than do populations in highly developed societies, in which it might be expected that higher hygiene standards are more widespread.

Potential pathways of virus–host interaction that may lead to T1D

What could be the pathological mechanisms that link viral infection to the onset of islet autoimmunity and eventually development of T1D? Several models have been postulated in attempts to answer this question.

Beta cell-specific viral infection

One possibility that was put forward by the work of Foulis and co-workers is that a beta cell-specific viral infection could have the ability to persist and initiate islet inflammation. It was demonstrated that recently diagnosed T1D patients harboured pancreatic islets that expressed aberrantly major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and interferon (IFN)-α[30]. Both molecules are up-regulated typically in response to viral infection and could be envisioned to cause recognition and killing of beta cells by infiltrating CD8 T cells. Some reports have indeed documented enterovirus infection specifically within pancreatic islets, and there seems to be a connection with an atypical ‘fulminant’ subtype of T1D [31]–[33]. Nevertheless, these results are in need of further confirmation using complementary detection techniques in order to gauge the precise frequency of beta cell-specific viral infection in T1D versus controls.

Molecular mimicry

The concept of ‘molecular mimicry’ suggests that viruses expressing epitopes resembling certain beta cell structures have the potential to induce cross-reactive immune responses [34]. Proof of concept was offered with the design of rat insulin promoter-lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus glycoprotein (RIP-LCMV.GP) transgenic mice, which develop diabetes after infection with LCMV [35],[36]. Some potential cross-reactivity has been documented in the past between Coxsackievirus constituents and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) [37],[38], a major autoantigen in T1D, but this correlation has since been challenged by others [39]–[41].

Thus, unlike classical examples of mimicry-induced autoimmunity such as seen in, e.g. rheumatic fever, solid support for a direct role in T1D development is currently lacking. An alternative scenario was proposed based on results in the RIP-LCMV model showing that sequential viral mimicry events can accelerate disease onset [42]. Such hypotheses are, of course, very difficult to test in a patient setting.

Bystander activation

In contrast, ‘bystander activation’ explains the recruitment and activation of autoaggressive cells to the islet milieu as a consequence of localized viral infection. Virus could lead to activation and maturation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), which would then shuttle antigen to the pancreatic draining lymph nodes resulting in priming of autoaggressive T cells [43]. The theory was strengthened by the finding that Coxsackievirus infection acts primarily by enhancing the release of islet antigens which, in turn, stimulate resting autoreactive T cells [39]. Bystander activation caused merely by cytokine release from inflammatory cells and infected cells is unlikely to be enough to break tolerance [44],[45] and by itself give rise to diabetes induction, as studies show that activation of APCs in the pancreas is required for T1D initiation in RIP-LCMV mice [46],[47]. The observation that enteroviruses are found predominantly around clinical diagnosis may support indirectly the idea that viral infection serves only as a non-specific, one-time trigger to allow pre-existing autoreactive T cells to reach their targets. Studies in the NOD mouse also revealed that a critical mass of autoimmunity is required for Coxsackievirus infections to be diabetogenic [48],[49]. One attractive mechanism would be that pancreotropic viruses can precondition the local vasculature to allow entry of effector T cells.

The ‘fertile-field hypothesis’

The ‘fertile-field hypothesis’ was conceived to explain how multiple microbial agents could culminate in potentially a single autoimmune disorder. Applied to T1D, the idea is that a viral infection with the right timing may give rise to a transient period, during which the pancreas becomes a fertile field for the development of autoimmune cells. Through induction of beta cell stress and activation of antigen drainage, self-epitopes are then released and presented to self-reactive T cells. In this context, we found recently that the contribution of apoptosis-related epitopes during spontaneous development in the NOD mouse appears to be limited [50], but this pathway could become enhanced after viral infection. The observation that diabetes acceleration in NOD mice by Coxsackievirus requires a critical level of inflammation contradicts this hypothesis, and indicates that insulitis may, in fact, serve as the ‘fertilizer’ for viruses to inflict any meaningful damage [48],[49].

Virus–gene interplay

Genetic predisposition is obviously a major factor in T1D development. Could it be that individuals with susceptibility genes for T1D possess a greater risk of productive infection or an inability to accurately respond to, e.g. enteroviral infections? Genetic studies indeed suggest that mutations in IFN-response genes might lie at the basis of an exaggerated response to viral infection in type 1 diabetes patients [51]. It should therefore be considered that the observed co-occurrence of enteroviruses and T1D reflects the host's inability to deal appropriately with a common, normally harmless infection. This is an interesting pathway to explore further, as it would shift the focus from genetic deficiencies leading to defective thymic deletion and tolerance towards pathways implicated in anti-viral immunity [52].

Can't find is not the same as not there

Finally, the failure to identify statistically solid associations with HEV in certain T1D patient populations might mean that we are missing out on some of the other culprits. Association of diseases with specific pathogens relies upon repeated observations of similar associations. For human T1D, there have been relatively few close associations of specific viruses with the disease and many more inferential associations (as, for example, rises in anti-viral antibody titres) [53]. Despite the excellence of murine models associating T1D with HEV infection (reviewed in [1],[11],[54]), another picornavirus – the cardiovirus encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) – has long been known to be able to induce T1D in mice [55],[56]. The finding that Saffold viruses, a relatively recently characterized group of human cardioviruses [57], are apparently widespread in the human population [12] alters this dynamic and raises the question: could there be other viruses associated more commonly and more specifically with human T1D than HEV? It will be worthwhile to explore this topic, perhaps initially by utilizing microarray tools [58] which can assay for diverse species of viruses within a single sample.

Arguments opposed to a role of viruses in the pathogenesis of T1D

‘Viral’ or ‘inflammatory’ signature?

Up-regulation of MHC class I as well as type 1 IFN and IFN-inducible chemokines such as CXCL10 has been observed in pancreata from T1D patients. All these markers are expressed typically in response to viral infection, but also as a consequence of generalized local inflammation. In mouse models, Seewald et al. demonstrated persistent up-regulation of MHC class I long after viral clearance in diabetic RAT-LCMV.GP transgenic mice [59]. This raises the question of whether MHC class I hyperexpression may be a mere consequence of ongoing inflammation rather than a result of ongoing infection.

Can (entero)viruses persist at all in the pancreas?

The mechanism by which persistence of HEV in the host can occur has been described recently [15],[16],[60]. Although shown only in cardiac tissue to date, it is not known whether a similar persistence can occur in other tissues, although there is no reason at this point to doubt that it could. The question devolves to how long might an HEV persist in any given tissue. We found MHC class I hyperexpression but no evidence of viral infection in any of the long-standing T1D donor pancreata acquired via the network for Pancreatic Organ Donors (nPOD, http://www.jdrfnpod.org; Coppieters et al. unpublished data), thus suggesting that up-regulation is not caused by any known virus.

Viral agents may represent a minor environmental component in T1D

Throughout history, many inconsistencies have accumulated in the literature with regard to studies linking detection of viral RNA or protein in blood, stool or pancreatic tissue to T1D onset. A recent meta-study by Yeung et al. [27] that included measurements of enterovirus RNA or viral capsid protein in blood, stool or tissue of patients with pre-diabetes and diabetes found a significant correlation. An earlier meta-study, in contrast, claimed that no convincing evidence existed for an association between Coxsackie B virus serology and T1D from the 26 examined studies that were included [61].

As mentioned above, these discrepancies could be explained by the involvement of several viral strains, many of which are still undiscovered, all of which may affect certain populations differentially. Further, it is possible that not a single event, but rather a series of infections is required and that transient infection stages escape detection in cross-sectional studies. Importantly, detection methods are far from standardized, and sensitivity thresholds can be expected to vary wildly. The option should be considered that viral agents represent only a small percentage of the environmental component in T1D and that significance is achieved only within certain susceptible populations. Finland, with its staggering T1D incidence, might be such a region where enteroviral strains contribute more aggressively compared to other countries.

Viral infection is an epiphenomenon

In a study by Richardson et al., the observation that 40% of type 2 diabetics showed that the presence of virus in their pancreatic islets may indicate that viral infection is an epiphenomenon to conditions of general beta cell stress [31]. The true infection frequency in T1D should therefore be considered vis-à-vis other forms of diabetes in order to exclude any secondary effects.

Viral infection is associated primarily with non-autoimmune subtypes of T1D

Finally, it is relevant to mention the aggressive T1D subtype known as ‘fulminant’ T1D. It is reported predominantly in the Japanese population and is characterized by the absence of autoantibodies, acute onset – often with ketoacidosis – and the almost complete destruction of beta cells at diagnosis. Patients with fulminant T1D often show symptoms of enterovirus infection prior to onset [62], and histological data demonstrate that a significant fraction of pancreata contain enteroviral particles [33]. The apparently strong correlation between enteroviruses and this unconventional, non-autoimmune disease phenotype could mean that at least some less-characterized donors [31] may have been affected by this disease subtype. Provided that our interest is in classical T1D as defined by autoantibodies and reactivity against islet antigens, this subtype may be considered a confounding factor that represents the extreme side of the spectrum, lacking the genetic component that is thought to be required in conventional T1D.

Conclusions

Several roadblocks exist currently on the road to understanding the role(s) played by viruses in human T1D. The first concerns which viruses may be involved. While it is clear that HEV can be players, other viruses that we have, as yet, not studied might be involved more specifically. A concerted effort needs to be directed towards this question to either confirm the primacy of HEV in this regard or to discover new aetiological agents. Closely related to this issue is how to associate viruses with the disease. Pancreatic biopsy is performed rarely and is difficult, and yet association of an infectious agent with a disease at the time of onset in the organ involved remains the gold standard by which such associations are judged. Due to this difficulty, type 1 diabetes researchers may have to be content with being one step removed, perhaps by screening serum and faeces aggressively at time of onset. This will, of course, require a more extensive data set in order to answer this question. Also, judging from experimental results, viruses may not only be a villain in this disease but may also have a salutary effect: evidence from experimental models and understanding human history and our environments suggest that virus exposure – at least HEV – could be beneficial through reducing the risk for developing autoimmune T1D. If true, and assuming as well that such viruses may also cause T1D in some people, then possessing an anti-viral protective immunity could be seen as a real clinical benefit: immunity to disease by specific HEV as well as an immunity to the development of autoimmune T1D. One key to determining if the latter may be true will be the examination of humans for the presence of protective regulatory T cells that have been induced by a specific viral infection, similar to results shown in mice.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (NIH-R01 I068818-03S1-04) and the Brehm Coalition.

Disclosure

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest are associated with this manuscript.

References

- 1.Tracy S, Drescher KM, Jackson JD, Kim K, Kono K. Enteroviruses, type 1 diabetes and hygiene: a complicated relationship. Rev Med Virol. 2010;20:106–16. doi: 10.1002/rmv.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Getts MT, Miller SD. 99th Dahlem conference on infection, inflammation and chronic inflammatory disorders: triggering of autoimmune diseases by infections. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:15–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stene LC, Rewers M. Immunology in the clinic review series; focus on type 1 diabetes and viruses: the enterovirus link to type 1 diabetes: critical review of human studies. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;168:12–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menser MA, Forrest J, Bransby R. Rubella infection and diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 1978;i:57–60. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oldstone MBA. Prevention of type 1 diabetes in NOD mice by virus infection. Science. 1988;239:500–2. doi: 10.1126/science.3277269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilberz S, Partke H, Dagnaes-Hansen F, Herberg L. Persistent MHV (mouse hepatitis virus) infection reduces the incidence of diabetes mellitus in non-obese diabetic mice. Diabetologia. 1991;34:2–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00404016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okada H, Kuhn C, Feillet H, Bach JF. The ‘hygiene hypothesis’ for autoimmune and allergic diseases: an update. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tracy S, Drescher KM, Chapman NM, et al. Toward testing the hypothesis that group B coxsackieviruses (CVB) trigger insulin-dependent diabetes: inoculating nonobese diabetic mice with CVB markedly lowers diabetes incidence. J Virol. 2002;76:12097–111. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.23.12097-12111.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatenoud L, You S, Okada H, Kuhn C, Michaud B, Bach JF. 99th Dahlem conference on infection, inflammation and chronic inflammatory disorders: immune therapies of type 1 diabetes: new opportunities based on the hygiene hypothesis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:106–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04125.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roep B, Atkinson MA, von Herrath MG. Satisfaction (not) guaranteed: re-evaluating the use of animal models of type 1 diabetes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:989–97. doi: 10.1038/nri1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drescher KM, Tracy S. The CVB and etiology of type 1 diabetes. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;323:259–74. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75546-3_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zoll J, Erkens Hulshof S, Lanke K, et al. Saffold virus, a human Theiler's-like cardiovirus, is ubiquitous and causes infection early in life. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000416. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grieco F, Sebastiani G, Spagnuolo I, Patti A, Dotta F. Immunology in the clinic review series; focus on type 1 diabetes and viruses: how viral infections modulate beta cell function. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;168:24–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim KS, Chapman NM, Tracy S. Replication of coxsackievirus B3 in primary cell cultures generates novel viral genome deletions. J Virol. 2008;82:2033–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01774-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chapman NM, Kim KS, Drescher KM, Oka K, Tracy S. 5′ terminal deletions in the genome of a coxsackievirus B2 strain occurred naturally in human heart. Virology. 2008;375:480–91. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim KS, Tracy S, Tapprich W, et al. 5′-Terminal deletions occur in coxsackievirus B3 during replication in murine hearts and cardiac myocyte cultures and correlate with encapsidation of negative-strand viral RNA. J Virol. 2005;79:7024–41. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.7024-7041.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lind K, Hühn MH, Flodström-Tullberg M. Immunology in the clinic review series; focus on type 1 diabetes and viruses: the innate immune response to enteroviruses and its possible role in regulating type 1 diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;168:30–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04557.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nerup J, Platz P, Andersen OO, et al. HL-A antigens and diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 1974;2:864–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Todd JA. Genetic analysis of type 1 diabetes using whole genome approaches. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8560–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Belle TL, Coppieters KT, von Herrath MG. Type 1 diabetes: etiology, immunology, and therapeutic strategies. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:79–118. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DIAMOND Project Group (WHO Multinational Project for Childhood Diabetes (DIAMOND) Research Group. Incidence and trends of childhood Type 1 diabetes worldwide 1990–1999. Diabet Med. 2006;23:857–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.EURODIAB ACE Study Group. Variation and trends in incidence of childhood diabetes in Europe. EURODIAB ACE Study Group. Lancet. 2000;355:873–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patterson CC, Dahlquist GG, Gyurus E, Green A, Soltesz G. Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989–2003 and predicted new cases 2005–20: a multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet. 2009;373:2027–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60568-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green A, Patterson CC. Trends in the incidence of childhood-onset diabetes in Europe 1989–1998. Diabtologia. 2001;44(Suppl 3):B3–8. doi: 10.1007/pl00002950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hyttinen V, Kaprio J, Kinnunen L, Koskenvuo M, Tuomilehto J. Genetic liability of type 1 diabetes and the onset age among 22,650 young Finnish twin pairs: a nationwide follow-up study. Diabetes. 2003;52:1052–5. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.4.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Filippi CM, von Herrath MG. 99th Dahlem conference on infection, inflammation and chronic inflammatory disorders: viruses, autoimmunity and immunoregulation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:113–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04128.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeung WC, Rawlinson WD, Craig ME. Enterovirus infection and type 1 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational molecular studies. BMJ. 2011;342:d35. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Filippi CM, Estes EA, Oldham JE, von Herrath MG. Immunoregulatory mechanisms triggered by viral infections protect from type 1 diabetes in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1515–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI38503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karvonen M, Tuomilehto J, Libmann I, LaPorte R. A review of the recent epidemiological data on the worldwide incidence of Type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. World Health Organization DIAMOND Project Group. Diabetologia. 1993;36:883–92. doi: 10.1007/BF02374468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foulis AK, Farquharson MA, Meager A. Immunoreactive alpha-interferon in insulin-secreting beta cells in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 1987;2:1423–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richardson SJ, Willcox A, Bone AJ, Foulis AK, Morgan NG. The prevalence of enteroviral capsid protein vp1 immunostaining in pancreatic islets in human type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1143–51. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dotta F, Censini S, van Halteren AG, et al. Coxsackie B4 virus infection of beta cells and natural killer cell insulitis in recent-onset type 1 diabetic patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5115–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700442104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka S, Nishida Y, Aida K, et al. Enterovirus infection, CXC chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10), and CXCR3 circuit: a mechanism of accelerated beta-cell failure in fulminant type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2009;58:2285–91. doi: 10.2337/db09-0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coppieters KT, von Herrath MG. Viruses and cytotoxic T lymphocytes in Type 1 diabetes. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2010;41:169–78. doi: 10.1007/s12016-010-8220-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohashi PS, Oehen S, Buerki K, et al. Ablation of ‘tolerance’ and induction of diabetes by virus infection in viral antigen transgenic mice. Cell. 1991;65:305–17. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90164-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oldstone MB, Nerenberg M, Southern P, Price J, Lewicki H. Virus infection triggers insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in a transgenic model: role of anti-self (virus) immune response. Cell. 1991;65:319–31. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90165-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atkinson MA, Bowman MA, Campbell L, Darrow BL, Kaufman DL, Maclaren NK. Cellular immunity to a determinant common to glutamate decarboxylase and coxsackie virus in insulin-dependent diabetes. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2125–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI117567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaufman DL, Erlander MG, Clare-Salzler M, Atkinson MA, Maclaren NK, Tobin AJ. Autoimmunity to two forms of glutamate decarboxylase in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:283–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI115573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horwitz MS, Bradley LM, Harbertson J, Krahl T, Lee J, Sarvetnick N. Diabetes induced by Coxsackie virus: initiation by bystander damage and not molecular mimicry. Nat Med. 1998;4:781–5. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richter W, Mertens T, Schoel B, et al. Sequence homology of the diabetes-associated autoantigen glutamate decarboxylase with coxsackie B4-2C protein and heat shock protein 60 mediates no molecular mimicry of autoantibodies. J Exp Med. 1994;180:721–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.2.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schloot NC, Willemen SJ, Duinkerken G, Drijfhout JW, de Vries RR, Roep BO. Molecular mimicry in type 1 diabetes mellitus revisited: T-cell clones to GAD65 peptides with sequence homology to Coxsackie or proinsulin peptides do not crossreact with homologous counterpart. Hum Immunol. 2001;62:299–309. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(01)00223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Christen U, Edelmann KH, McGavern DB, et al. A viral epitope that mimics a self antigen can accelerate but not initiate autoimmune diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1290–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI22557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.von Herrath MG, Fujinami RS, Whitton JL. Microorganisms and autoimmunity: making the barren field fertile? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2003;1:151–7. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Herrath MG, Allison J, Miller JF, Oldstone MB. Focal expression of interleukin-2 does not break unresponsiveness to ‘self’ (viral) antigen expressed in beta cells but enhances development of autoimmune disease (diabetes) after initiation of an anti-self immune response. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:477–85. doi: 10.1172/JCI117688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holz A, Brett K, Oldstone MB. Constitutive beta cell expression of IL-12 does not perturb self-tolerance but intensifies established autoimmune diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1749–58. doi: 10.1172/JCI13915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.von Herrath M, Holz A. Pathological changes in the islet milieu precede infiltration of islets and destruction of beta-cells by autoreactive lymphocytes in a transgenic model of virus-induced IDDM. J Autoimmun. 1997;10:231–8. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1997.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garza KM, Chan SM, Suri R, et al. Role of antigen-presenting cells in mediating tolerance and autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2000;191:2021–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.11.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Serreze DV, Ottendorfer EW, Ellis TM, Gauntt CJ, Atkinson MA. Acceleration of type 1 diabetes by a coxsackievirus infection requires a preexisting critical mass of autoreactive T-cells in pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 2000;49:708–11. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.5.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Drescher KM, Kono K, Bopegamage S, Carson SD, Tracy S. Coxsackievirus B3 infection and type 1 diabetes development in NOD mice: insulitis determines susceptibility of pancreatic islets to virus infection. Virology. 2004;329:381–94. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coppieters KT, Amirian N, von Herrath MG. Incidental CD8 T cell reactivity against caspase-cleaved apoptotic self-antigens from ubiquitously expressed proteins in islets from prediabetic human leucocyte antigen-A2 transgenic non-obese diabetic mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;165:155–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smyth DJ, Cooper JD, Bailey R, et al. A genome-wide association study of nonsynonymous SNPs identifies a type 1 diabetes locus in the interferon-induced helicase (IFIH1) region. Nat Genet. 2006;38:617–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jaïdane H, Sané F, Hiar R, et al. Immunology in the clinic review series; focus on type 1 diabetes and viruses: enterovirus, thymus and type 1 diabetes pathogenesis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;168:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hober D, Sane F, Jaïdane H, Riedweg K, Goffard A, Desailloud H. Immunology in the clinic review series; focus on type 1 diabetes and viruses: role of antibodies enhancing the infection with Coxsackievirus-B in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;168:47–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04559.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tracy S, Drescher KM. Coxsackievirus infections and NOD mice: relevant models of protection from, and induction of, type 1 diabetes. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1103:143–51. doi: 10.1196/annals.1394.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Craighead JE. The role of viruses in the pathogenesis of pancreatic disease and diabetes mellitus. Prog Med Virol. 1975;19:161–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoon J, Jun H. Viruses can cause type 1 diabetes in animals. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1079:138–46. doi: 10.1196/annals.1375.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chiu CY, Greninger AL, Kanada K, et al. Identification of cardioviruses related to Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus in human infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14124–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805968105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang D, Coscoy L, Zylberberg M, et al. Microarray-based detection and genotyping of viral pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15687–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242579699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seewaldt S, Thomas HE, Ejrnaes M, et al. Virus-induced autoimmune diabetes: most beta-cells die through inflammatory cytokines and not perforin from autoreactive (anti-viral) cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. Diabetes. 2000;49:1801–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.11.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chapman NM, Kim K-S. Persistent coxsackievirus infection: enterovirus persistence in chronic myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;323:275–92. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75546-3_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Green J, Casabonne D, Newton R. Coxsackie B virus serology and Type 1 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of published case–control studies. Diabet Med. 2004;21:507–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hanafusa T, Imagawa A. Fulminant type 1 diabetes: a novel clinical entity requiring special attention by all medical practitioners. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3:36–45. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0351. quiz 2 pp. following p. 69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]