Abstract

Evidence for microbial Fe redox cycling was documented in a circumneutral pH groundwater seep near Bloomington, Indiana. Geochemical and microbiological analyses were conducted at two sites, a semi-consolidated microbial mat and a floating puffball structure. In situ voltammetric microelectrode measurements revealed steep opposing gradients of O2 and Fe(II) at both sites, similar to other groundwater seep and sedimentary environments known to support microbial Fe redox cycling. The puffball structure showed an abrupt increase in dissolved Fe(II) just at its surface (∼5 cm depth), suggesting an internal Fe(II) source coupled to active Fe(III) reduction. Most probable number enumerations detected microaerophilic Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria (FeOB) and dissimilatory Fe(III)-reducing bacteria (FeRB) at densities of 102 to 105 cells mL−1 in samples from both sites. In vitro Fe(III) reduction experiments revealed the potential for immediate reduction (no lag period) of native Fe(III) oxides. Conventional full-length 16S rRNA gene clone libraries were compared with high throughput barcode sequencing of the V1, V4, or V6 variable regions of 16S rRNA genes in order to evaluate the extent to which new sequencing approaches could provide enhanced insight into the composition of Fe redox cycling microbial community structure. The composition of the clone libraries suggested a lithotroph-dominated microbial community centered around taxa related to known FeOB (e.g., Gallionella, Sideroxydans, Aquabacterium). Sequences related to recognized FeRB (e.g., Rhodoferax, Aeromonas, Geobacter, Desulfovibrio) were also well-represented. Overall, sequences related to known FeOB and FeRB accounted for 88 and 59% of total clone sequences in the mat and puffball libraries, respectively. Taxa identified in the barcode libraries showed partial overlap with the clone libraries, but were not always consistent across different variable regions and sequencing platforms. However, the barcode libraries provided confirmation of key clone library results (e.g., the predominance of Betaproteobacteria) and an expanded view of lithotrophic microbial community composition.

Keywords: neutral pH, microbial, iron, cycling, microscale, 16S rRNA gene, barcode sequencing

Introduction

Redox cycling of iron (Fe) is a key process governing carbon and energy flow and the speciation and mobility of a wide variety of aqueous and solid-phase constituents in soils and sediments. Both reduction and oxidation of Fe are microbially catalyzed, and available evidence suggests that microbial Fe redox cycling takes place across a wide range of modern natural environments, including acidic and circumneutral pH soil/sediment (Peine et al., 2000; Sobolev and Roden, 2002; Roden et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2009; Lu et al., 2010; Coby et al., 2011) and groundwater seep systems (Emerson and Revsbech, 1994a; Emerson et al., 1999; Blöthe and Roden, 2009; Duckworth et al., 2009; Emerson, 2009; Bruun et al., 2010). Fe-based microbial ecosystems are hypothesized to be ancient, with both Fe(III)-reducing and Fe(II)-oxidizing microbes deeply rooted in the universal phylogenic tree (Emerson et al., 2010). Fe redox cycling is likely to have played a major role in the global biogeochemistry of Earth during the Archaean and early Proterozoic Eons (Walker, 1984; Konhauser et al., 2002, 2005), when massive deposition of Fe rich sediments (banded iron formations) occurred in association with the slow conversion of the atmosphere and oceans from anoxic to oxic conditions (Holland and Kasting, 1992). In addition, sedimentological, geochemical, and microfossil evidence suggest that Fe redox cycling took place in ancient (ca. two billion year old) layered microbial communities (Planavsky et al., 2009; Schopf et al., 2010).

Although the abiotic oxidation of Fe(II) is very rapid at neutral pH (half-life of ca. 5 min in air-saturated solution at pH 7), various studies have demonstrated that microbial (enzymatic) oxidation can compete effectively with abiotic oxidation under microaerobic (<10% air saturation) conditions (Roden et al., 2004). Microbial Fe(II) oxidation in modern neutral pH freshwater environments is typically dominated by Betaproteobacteria, principally members of the Gallionellaceae family (genera Gallionella and Sideroxydans) and the Burkholderiales-related genus Leptothrix (James and Ferris, 2004; Duckworth et al., 2009; Bruun et al., 2010; Fleming et al., 2011). Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria (FeOB) from the Rhodocyclaceae (Sobolev and Roden, 2004) and Comamonadaceae (genus Comamonas; Blöthe and Roden, 2009) have also been identified in such environments. At neutral pH, microbial Fe(II) oxidation produces Fe(III) oxides which can be readily used as electron acceptors for dissimilatory Fe(III)-reducing bacteria (FeRB; Emerson and Revsbech, 1994a; Straub et al., 1998; Blöthe and Roden, 2009; Emerson, 2009; Langley et al., 2009). FeRB are a diverse taxa which couple the oxidation of organic carbon or H2 to the reduction of soluble and solid-phase Fe(III) forms (Lovley et al., 2004). Microbial Fe(III) oxide reduction results in Fe(II) regeneration, thus perpetuating a coupled Fe redox cycle given an input of organic matter to fuel Fe(III) reduction (Roden et al., 2004; Blöthe and Roden, 2009). The close spatial and metabolic coupling of microbial Fe reduction and oxidation has been proposed in various environments where an oxic/anoxic transition zone is observed (Sobolev and Roden, 2002; Roden et al., 2004; Haaijer et al., 2008; Blöthe and Roden, 2009; Bruun et al., 2010). However, details regarding the interaction between FeOB and FeRB and their activities in situ are not yet fully understood, e.g., compared to the detailed level of knowledge available on microbial sulfur cycling in microbial mats (Decho et al., 2010).

The spatial/temporal dynamics of Fe oxidation and reduction has critical implications for the abundance and persistence of reactive Fe(III) oxides in soils and sediments. This in turn may have a major influence on the migration of metals (e.g., divalent cations) and radionuclides with a high affinity for Fe(III) oxide surfaces, specifically in situations where Fe(II) and mobilized metals enter more oxidizing environments on the fringes of reducing zones, or where O2 containing groundwater impinges on reduced zones. Comparatively little information is available on how FeOB and FeRB interact in these situations. Though not direct analogs to sedimentary environments, groundwater Fe seeps provide a convenient natural laboratory for studies of microbial Fe redox cycling. They are typically easily accessible, contain FeOB and FeRB capable of Fe redox cycling, and display spatial and temporal dynamics that are likely to be similar (though not in an absolute way) to those in the subsurface. In particular, mat structures in groundwater seeps tend to display millimeter-to-centimeter scale redox gradients analogous to those present in aquatic surface sediments (e.g., see Roden and Emerson, 2007) and physically/chemically heterogenous aquifer materials (e.g., see Hunter et al., 1998; Jakobsen, 2007). Thus, groundwater Fe seeps are both interesting in their own right and provide a conceptual analog to the myriad of surface and subsurface environments where Fe redox transformations may play a critical role in biogeochemical cycling.

This contribution provides a combined geochemical and microbiological investigation of a circumneutral pH groundwater Fe seep near Bloomington, IN, USA. This seep has been the subject of a limited range of prior work in the context of microbial mat formation (Scheiber, 2004; Schieber and Glamoclija, 2007). Voltammetric microelectrodes were employed to determine the in situ distribution of O2 and soluble Fe species. The potential for native microbial communities to contribute to Fe cycling was assessed through most probable number (MPN) enumerations as well as in vitro Fe(III) reduction experiments. The limited microbial diversity within the seep allowed us to investigate several approaches for 16S rRNA gene analysis of microbial communities involved in Fe cycling. Both conventional full-length 16S rRNA gene clone libraries and high throughput barcode sequencing approaches (Illumina and 454) using either the V1, V4, or V6 regions of the 16S rRNA gene were employed to interrogate microbial community composition.

Materials and Methods

Field site

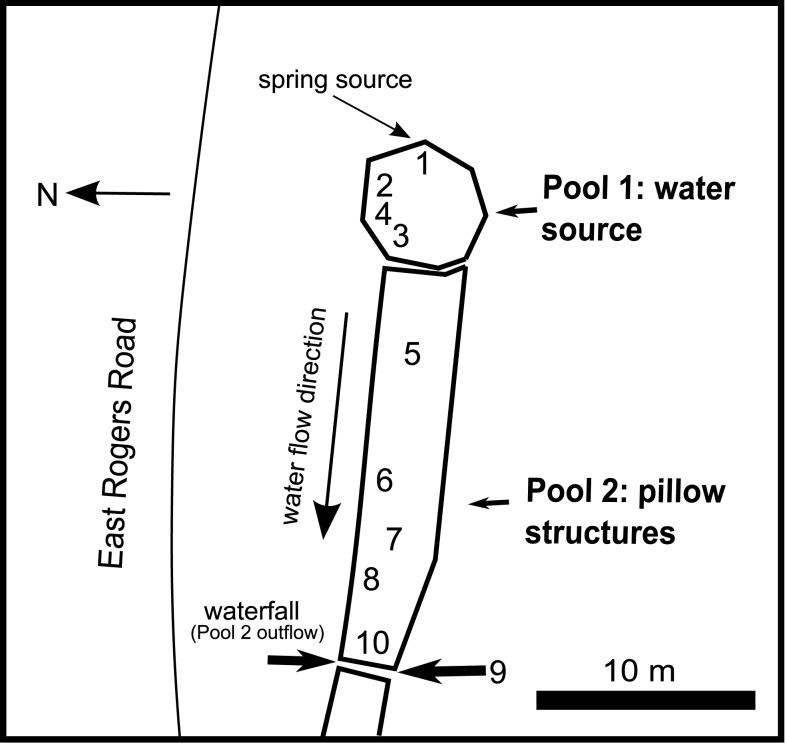

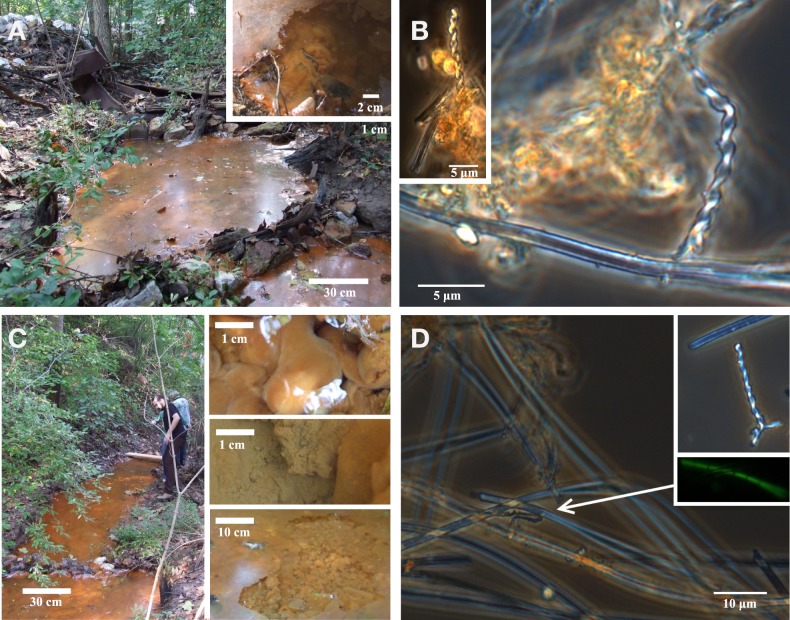

Samples were collected in September 2008 from a groundwater seep in Jackson Creek near Bloomington, IN, USA (Figure 1). Flocculant, reddish brown Fe(III) oxide deposits are prominent at this site (Figure 2) due to oxidation of Fe(II) released during weathering of authigenic pyrite in the local subsurface (Schieber and Glamoclija, 2007). Ten locations were used to characterize the geochemistry of the site as a whole. Of these 10 sites, two areas were chosen for sample collection (see Figures 1 and 2): site 2, the top few cm of a semi-consolidated microbial mat; and site 7, a floating “puffball” structure that resembled a loose sphere with pillowy morphology. These sites will be referred to hereafter as the “microbial mat” (or “mat”) and the “puffball,” respectively. While mat-like structures are common to virtually all groundwater Fe seeps, puffball structures are site specific, and typically not present in fast flowing environments. However, they are not uncommon in slow flowing sites like the one studied here, and they provide an interesting contrast to mats in terms of the dimensions and dynamics of Fe redox cycling.

Figure 1.

Map of groundwater seep site in Bloomington, IN, USA. Numbers indicate sampling sites.

Figure 2.

Photos of field site and corresponding light microscopy images. Pool 1 (A,B) is the source zone for the seep; note semi-consolidated Fe(III) oxide mats (inset). Pool 2 (C,D) is downstream from Pool 1; inset shows images of puffball structures. Light microscopy images show stalk and sheath structures typical of microaerophillic FeOB at both sites.

Geochemical measurements

Temperature and pH were measured in the field using a portable thermistor and combination electrode. Field voltammetry was performed in situ at the 10 sampling sites, as well as on undisturbed materials from the microbial mat and the puffball. The survey measurements were made by placing the electrode several mm below the water surface. At sites 2 and 7, the voltammetric equipment and a micromanipulator were set up on a small wooden platform installed over a selected portion of the seep where lateral flow was minimal (Figure 3). Voltammetry allowed direct, in situ, measurement of the chemical species present in depth profiles with minimal perturbation during analysis. This system has proven to be very useful for analyzing a wide variety of redox species in a number of environments, including O2, H2O2, Fe2+, Fe3+, FeS(aq), Mn2+, H2S, S8, and (Brendel and Luther, 1995; Rentz et al., 2007; Druschel et al., 2008; Luther et al., 2008). For analyses in the field, a DLK-100A Potentiostat (Analytical Instrument Systems, Flushing, NJ, USA) was employed with a computer controller and software.

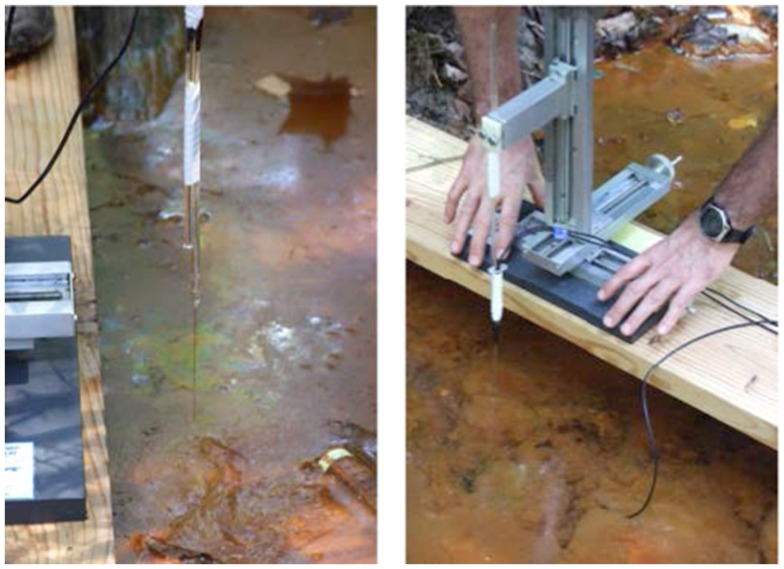

Figure 3.

Photos of voltammetric microelectrode deployment in the microbial mat (left) and the puffball (right). The microbial mat was essentially on the surface, whereas the puffball was overlain by about 10 cm of water.

A standard three-electrode system was used for all measurements and two versions were employed. In the first version, the working, reference, and counter electrodes were in separate glass or plastic housings. The working electrode was 0.1 mm diameter gold amalgam (Au/Hg) made by placing Au wire in a 5-mm glass tube drawn out to a 0.2- to 0.3-mm tip. The electrode was constructed, polished, and then plated with Hg after standard practices (Brendel and Luther, 1995; Luther et al., 2008). An Ag/AgCl reference electrode and a Pt counter electrode (both 0.5 mm wires encased in plastic) were placed in the water near the measurement site. The working electrode was mounted on a three-axis micromanipulator (CHPT manufacturing, Georgetown, DE, USA) operated by hand to descend in increments between 0.1 mm or larger increments for each sampling point. A second, more durable type of electrode was made with the Au wire housed in a stainless steel hypodermic needle (1.65 mm diameter by 75 or 125 mm length), which was used as the counter electrode. The working electrode was a 0.125-mm gold wire encased in Teflon (A-M systems, Inc.). Connector wires were attached to the Au wire and the stainless steel needle, and the top part of the working and counter electrodes were encased in rigid Teflon tubing. A non-conductive epoxy was used to stabilize the Au wire, stainless steel needle, and Teflon as one complete two electrode system (working and counter). The tip was polished and plated as above and mounted on the three-axis micromanipulator. The reference electrode was a separate 0.5 mm Ag/AgCl electrode as described above.

Electrochemical measurements began when the working electrode was carefully lowered to the point where the water surface tension was broken and the tip was as close to the surface as possible (defined as 0 depth). Cyclic voltammetry was performed in triplicate at each sampling point in the profile at 1000 mV/s between −0.1 and −1.8 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) with an initial potential of −0.1 V held for 2 s. In order to keep the working electrode surface clean, the electrode was held at −0.9 V between sampling scans.

Calibration of the electrodes was accomplished by standard addition methods using waters collected at the site and filtered through a 0.2-μm nuclepore filter. For O2 standardization, natural waters were purged with air and then purged with ultra high-purity (UHP) argon to remove O2; the O2 detection limit was 3–5 μM. Sample water was also purged with UHP argon and then spiked with stock solutions of FeCl2, MnCl2, and Na2S (ACS grade reagents). The water for the standards was purged with UHP argon before preparation. Detection limits for Fe(II), Mn(II), thiosulfate, and sulfide are 10, 5, 30, and 0.2 μM respectively.

In vitro Fe(III) reduction experiments

Fe(III) reduction experiments were conducted with mat and puffball materials to determine the potential for native microbial communities to reduce the Fe(III) phases present, without exogenous electron donor addition. Duplicate sealed, N2-flushed 60-mL serum bottles were completely filled with a suspension of materials from each site. Small subsamples (0.5 mL) were collected over time (using a N2-flushed syringe and needle) for 0.5 M HCl extraction (1 h) and Fe(II) determination using the Ferrozine assay (Stookey, 1970).

MPN determinations

A three-tube MPN technique was used to enumerate FeOB and FeRB, as well as aerobic and anaerobic heterotrophic organisms in materials from the mat and puffball. MPN values were calculated from standard MPN tables (Woomer, 1994). Aerobic and anaerobic (fermentative) heterotrophs were grown in tryptic soy broth (0.25% TSB) medium (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA); tubes were scored positive by visual turbidity. A carbonate buffered (pH 6.8) freshwater medium (Widdel and Bak, 1992), was used for cultivation of FeRB and aerobic FeOB. For enumeration of FeRB, natural Fe(III) oxide (freeze-dried and autoclaved) from the groundwater Fe seep described in Blöthe and Roden (2009) was utilized at a final concentration of ca. 20 mmol L−1. Either H2 (10% in headspace) or a mix of 5 mM acetate and 5 mM lactate was used as the electron donor. Tubes for Fe(III) reduction were scored positive by measurement of Fe(II) formation. FeOB were enumerated in Fe(II)-O2 opposing gradient cultures as described elsewhere (Sobolev and Roden, 2001). Tubes were scored positive by the formation of a compact growth band of cells plus Fe(III) oxide, as compared to the more diffuse band of Fe(III) oxide precipitation that formed in uninoculated controls (Emerson and Moyer, 1997). All MPN tubes were incubated between 1 and 4 weeks at room temperature.

DNA extraction and microbial community analysis

DNA was extracted from samples collected from sites 2 and 7 using the Mo Bio PowerSoil® (Mo Bio, Carlsbad, CA, USA) DNA Isolation Kit. Near full-length 16S rRNA gene clone libraries were constructed using primers GM3F and GM4R (Muyzer et al., 1995). Clones were constructed using the pGEM-T vector and Escherichia coli JM109 competent cells (Promega). 16S rRNA gene sequences of recombinant transformants were obtained from the University of Wisconsin–Madison Biotechnology Center. Assembled clones were screened for chimeras using UCHIME (Edgar et al., 2011) and flagged sequences were subsequently examined in Pintail (Ashelford et al., 2005). Suspicious sequences were excluded from downstream analyses. The resulting sequences were aligned to the SILVA database (Pruesse et al., 2007), filtered using Mothur (Schloss et al., 2009; Schloss, 2010; version 1.22.0), and a distance matrix was generated. The sequences were clustered to identify unique OTUs at the 97% level, and taxonomies were assigned using the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) classifier (Wang et al., 2007) employing a modified database optimized for detection of neutral pH FeOB. The classifications were bootstrapped 1000 times and taxonomic assignments were only made for bootstrap values of greater than 60%. Unique sequences were submitted to GenBank (accession numbers JQ906267–JQ906408).

High throughput barcode sequencing of PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene fragments from sites 2 and 7 was completed by Mitch Sogin and colleagues at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) at Woods Hole, MA, and Noah Fierer and colleagues the University of Colorado, Boulder. These sequencing analyses were performed on the same DNA extracts used to construct the clone libraries. Primers 967F and 1046R were used to target the V6 region of the 16S rRNA gene (Kysela et al., 2005; Sogin et al., 2006), and the amplicons were sequenced at MBL using the Roche 454 GS20 platform (∼60 bp reads). Primers 515F and 806R were used to target the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene (Bates et al., 2011; Caporaso et al., 2010), and the amplicons were sequenced at EnGenCorp (University of South Carolina) using either the Roche 454 GS FLX platform (∼240 bp reads) or the Illumina GAIIx platform (∼100 bp reads). Illumina sequencing was also completed using primers 27F and 338R that targeted the V1 region of the 16S rRNA gene (∼80 bp reads; Hamady et al., 2008). The use of different sequencing platforms and regions of the 16S rRNA gene provided good technical replication for these samples.

Barcoded reads were processed using Mothur: the data were denoised using the Mothur implementation of the AmpliconNoise algorithm (Quince et al., 2011), barcodes and primers were removed, sequences were aligned to the SILVA database and filtered, chimeras were detected using UCHIME and removed, and all sequences were classified using a modified RDP classifier as described above for the clone library sequences.

Results

Geochemical measurements

Water temperature and pH showed little variation across the sampling transect (see Figure 1; Table 1), ranging from 14.9 to 15.9°C, and 6.4–6.6 respectively. Voltammetric measurements revealed O2 concentrations below the detection limit of ca. 3 μM within a cm of the water–air interface at all but one site. Relatively high concentrations of dissolved Fe(II) (ca. 320–450 μM) were present at all sites; low levels of dissolved Mn(II) were detected at sites 4 (49 μM) and 6 (14 μM). Detectable quantities of dissolved or complexed Fe(III) were observed at all but one site; note that these are qualitative estimates only (expressed in units of nA, 3–50 nA) due to lack of site specific Fe(III) standards (Luther et al., 2008).

Table 1.

Results of geochemical survey.

| Survey site | Temp (°C) | pH | O2 (μM) | Fe(II) (μM) | Mn(II) (μM) | Fe(III) (nA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | 14.9 | 6.44 | BDa | 322 | BD | 3.5 |

| Site 2 (microbial mat) | 15.1 | 6.49 | BD | 355 | BD | 30 |

| Site 3 | 15.1 | 6.45 | BD | 367 | BD | BD |

| Site 4 | 15.6 | 6.50 | BD | 307 | 49 | 22 |

| Site 5 | 15.4 | 6.52 | BD | 406 | BD | 23 |

| Site 6 | 15.8 | 6.54 | BD | 338 | 14 | 11 |

| Site 7 (puffball) | 15.7 | 6.47 | BD | 394 | BD | 20 |

| Site 8 | 15.8 | 6.53 | BD | 336 | BD | 28 |

| Site 10 | 15.9 | 6.53 | BD | 443 | BD | 15 |

| Site 9 | 15.9 | 6.60 | BD | 328 | BD | 51 |

aBelow detection.

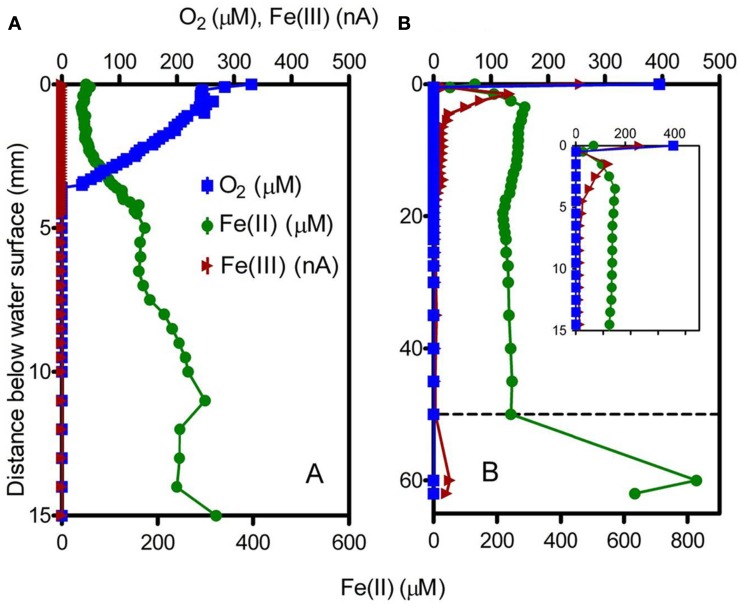

Voltammetric depth profiling at sites 2 (microbial mat) and 7 (puffball) revealed a sharp decrease in O2 within a few mm of the water surface (Figure 4). The transition from oxic to very low (<3 μM) O2 conditions took place at ca. 4 mm depth in the microbial mat, compared to less than 1 mm in water overlying the puffball structure. Dissolved Fe(II) and O2 coexisted within the upper few mm of the mat, below which Fe(II) concentrations gradually increased. In contrast, dissolved Fe(II) concentrations were nearly uniform within the water column above the puffball, following a sharp increase within the upper ca. 2 mm. A second abrupt increase in dissolved Fe(II) concentration was detected during transection of the upper boundary of the puffball structure at ca. 5 cm depth. Dissolved Fe(III) was present within the upper few mm at the puffball site, but below detection within the mat.

Figure 4.

Voltammetric microelectrode profiles for the microbial mat (A) and the puffball structure (B). Dashed line in (B) indicates the approximate surface of the flocculant puffball structure; inset shows an expanded scale of the first 15 mm.

MPN enumerations and in vitro Fe(III) reduction

Most probable number enumerations revealed substantial numbers of culturable FeOB and FeRB (102 to 105 cells mL−1) in both the mat and puffball materials (Table 2). The abundance of these organisms was 10- to 1000-fold lower than culturable aerobic and anaerobic heterotrophs. The presence of culturable FeRB was consistent with the results of the in vitro Fe(III) reduction experiments, which showed the potential for Fe(III) reduction during anoxic incubation of materials from both sites (Figure 5). Fe(II) concentrations leveled off after ca. 25 days, likely due to depletion of electron donors, as no exogenous organic matter was added to the oxide suspensions. Detectable Fe(III) reduction took place within an hour after isolation of the puffball material in sealed, completely filled serum bottles. An initial decline in Fe(II) was observed during the first day of incubation of the mat material, likely due to oxidation of Fe(II) by O2 entrained during transfer of the flocculant material to the serum bottles. Despite the initial difference in behavior for the two samples, when integrated over the 25-day incubation period, first-order rate constants for Fe(III) reduction were quite similar (ca. 0.085 and 0.083 day−1 for the mat and puffball materials, respectively; see Figure 5).

Table 2.

Most probable number values for different types of microorganisms in materials from the microbial mat and puffball.

| Physiological group | MPN, cells mL−1 (±range) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Microbial mat (site 2) | Puffball (site 7) | |

| Aerobic heterotrophs | 5.13 × 107 (±4.69 × 107) | 5.39 × 106 (±4.92 × 106) |

| Anaerobic heterotrophs | 2.15 × 107 (±1.97 × 106) | 9.52 × 103 (±8.68 × 103) |

| Fe(III) reducers with acetate/lactatea | 6.82 × 105 (±2.54 × 105) | 9.78 × 103 (±8.92 × 103) |

| Fe(III) reducers with hydrogena | 2.20 × 104 (±2.01 × 104) | 8.57 × 102 (±7.83 × 102) |

| Aerobic Fe(II) oxidizers | 1.71 × 103 (±1.56 × 103) | 7.84 × 103 (±7.16 × 103) |

Figure 5.

In vitro Fe(III) reduction in materials from the microbial mat and puffball. Symbols show the average ratio of Fe(II) to total Fe in 0.5 M HCl extracts from duplicate cultures; lines show results of non-linear least-squares regression fits of the Fe(II) accumulation data to an integrated first-order rate law Fe(II)t = Fe(II)0 + [Fe(II)max − Fe(II)0] × [1 − exp(-kredt)]. Estimated kred values were 0.085 and 0.083 day−1 for the microbial mat and puffball materials, respectively.

Molecular microbial community analysis

Clone libraries

The 16S rRNA gene clone libraries revealed modest phylogenetic diversity in the mat and puffball materials (Figure 6). A total of 12 families comprising 18 genera were identified (Table 3). Proteobacteria were the dominant components of the libraries, accounting for ≥95% of all clones at both sites (Figure 7). Betaproteobacteria in turn accounted for ca. 95 and 50% of Proteobacteria in the mat and puffball libraries, respectively, with Gammaproteobacteria and Deltaproteobacteria being much more abundant in the puffball libraries.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic tree constructed from 16S rRNA gene clones from sites 2 (microbial mat) and 7 (puffball). The number of clones from each of sites 2 and 7 and the number of reference sequences (where used) are indicated beside each taxon in parentheses (number of site 2 clones, number of site 7 number of clones; number of reference sequences). The values in the triangles indicate the number of unique clones from each site and the number of reference sequences used to construct the tree in arb, respectively (values separated by commas). The tree was prepared using neighbor joining analysis with Jukes–Canter correction. Percentages on nodes represent 1000 bootstrap analyses; only values greater than 50% are shown. More details on major taxa identified in each sample are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of taxa identified in the 16S rRNA gene clone libraries.

| Site | Family | Genus | % Total | Representative pure culture match | Accession No. | Similarity (%) | Physiology | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial mat (61 clones) | Gallionellaceae | Gallionella | 37.7 | Gallionella capsiferriformans ES-2 | CP002159.1 | 96–97 | Fe(II) Ox, O2 red | Emerson and Moyer (1997) |

| Unclassified Burkholderiales | Aquabacterium | 29.5 | Denitrifying Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria | U51102.1 | 99 | Fe(II) Ox, red | Buchholz-Cleven et al. (1997) | |

| Gallionellaceae | Candidatus Nitroga | 11.5 | Sulfuricella denitrificans | AB506456.1 | 92 | S0/ Ox, O2/ red | Kojima and Fukui (2010) | |

| Comamonadaceae | Rhodoferax | 8.2 | Rhodoferax ferrireducens T118 | CP000267.1 | 92 | Fe(III) red | Finneran et al. (2003) | |

| Gallionellaceae | Sideroxydans | 6.6 | Sideroxydans lithotrophicus ES-1 | CP001965.1 | 94–96 | Fe(II) Ox, O2 red | Emerson and Moyer (1997) | |

| Unclassified Bacteroidetes | Unclassified Bacteroidetes | 6.6 | Bacteroidetes bacterium RL-C | AB611036.1 | 84–94 | Fermentation | Qiu and Sekiguchi, unpublished | |

| Puffball (80 clones) | Gallionellaceae | Sideroxydans | 15.0 | Sideroxydans lithotrophicus ES-1 | CP001965.1 | 97–99 | Fe(II) Ox, O2 red | Emerson and Moyer (1997) |

| Methylococcaceae | Methylobacter | 13.8 | Methylobacter sp. BB5.1 | AF016981.1 | 94–96 | CH4 Ox, O2 red | Smith et al. (1997) | |

| Comamonadaceae | Comamonas | 11.3 | Comamonas sp. IST-3 | DQ386262.1 | 100 | Fe(II) Ox, O2 red | Blöthe and Roden (2009) | |

| Desulfovibrionaceae | Desulfovibrio | 10.0 | Desulfovibrio putealis strain B7-43 | NR–029118.1 | 99 | red; Fe(III) red | Basso et al. (2005); Lovley et al. (1993) | |

| Aeromonadaceae | Aeromonas | 8.8 | Aeromonas hydrophila strain ATCC 7966 | X60404.2 | 98 | Fe(III) red | Knight and Blakemore (1998) | |

| Unclassified Burkholderiales | Aquabacterium | 7.5 | Denitrifying Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria | U51102.1 | 99 | Fe(II) Ox, red | Buchholz-Cleven et al. (1997) | |

| Rhodocyclaceae | Propionivibrio | 7.5 | Propionivibrio limicola strain GolChi1 | NR–025455.1 | 97 | Fermentation | Brune et al. (2002) | |

| Bacillaceae | Bacillus | 6.3 | Bacillus sp. MB-5 | AF326363.1 | 99 | Ferm; Mn(II) Ox, O2 red | Francis and Tebo (2002) | |

| Rhodocyclaceae | Rhodocyclus | 5.0 | Rhodocyclus tenuis strain DSM110 | D16209.1 | 97 | Anoxygenic Phototroph | Hiraishi (1994) | |

| Unclassified Clostridiales | Blautia | 3.8 | Eubacterium plexicaudatum ASF 492 | AF157054.1 | 94 | Fermentation | Dewhirst et al. (1999) | |

| Geobacteraceae | Geobacter | 3.8 | Geobacter sp. strain CdA-2 | Y19190.1 | 96 | Fe(III) red | Cummings et al. (2000) | |

| Methylococcaceae | Methylosarcina | 2.5 | Methylosarcina lacus strain LW14 | NR–042712.1 | 96 | CH4 Ox, O2 red | Kalyuzhnaya et al. (2005) | |

| Hyphomicrobiaceae | Rhodoplanes | 1.3 | Alphaproteobacterium Shinshu-th1 | AB121772.1 | 96 | Aerobic Heterotroph | Hamaki et al. (2005) | |

| Comamonadaceae | Hylemonella | 1.3 | Ottowia thiooxydans strain K11 | NR–029001.1 | 100 | Ox, O2/ red | Spring et al. (2004) | |

| Gallionellaceae | Gallionella | 1.3 | Gallionella capsiferriformans ES-2 | CP002159.1 | 96–97 | Fe(II) Ox, O2 red | Emerson and Moyer (1997) | |

| Crenotrichaceae | Crenothrix | 1.3 | Methylomonas sp. LW15 | AF150794.1 | 94 | CH4 Ox, O2 red | Costello and Lidstrom (1999) |

Taxa related to known FeOB and Fe(III) reducing organisms are shown in bold in the Physiology column.

Figure 7.

Relative abundance of taxa at the phylum/class level in the 16S rRNA gene clone and barcode libraries from sites 2 (microbial mat) and 7 (puffball). V1, V4, and V6 refer to different variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene; 454 refers to the Roche 454 GS20 (V6) or GS FLX (V4) platform; Illumina refers to the Illumina GAIIx platform. See Tables 4 and 5 for a more detailed taxonomic breakdown of the components of the different libraries.

Simple inspection of the phylogenetic assignments suggested the presence of recognized Fe(II)-oxidizing and Fe(III)-reducing taxa (see below). A series of BLAST searches was conducted to gain further insight into the potential physiological capacities of the specific taxa detected in the libraries. Although caution must exercised in inferring physiology based on 16S rRNA gene similarity (Achenbach and Coates, 2000), this basic approach, pioneered by Pace (1996, 1997), remains standard practice in microbial ecology. BLAST was used not to exhaustively catalog phylogenetic relatives to the clone sequences, but rather to search for possible evidence of Fe redox metabolic capacity in the identified taxa (see Table 3). We focused on pure culture relatives of the clone sequences, for which reasonable physiological inferences could be made. In some cases, the top BLAST matches corresponded to organisms in pure culture that are known to carry out Fe redox metabolism; in other cases, matches to organisms with such physiology were further down in the list of BLAST hits. Only matches with ≥95% sequence similarity (nominal cut-off for assigning genus-level affiliation; Gillis et al., 2001) were considered, except in cases where the top match had a lower degree of similarity.

The most abundant clones in both libraries were closely related to the well known microaerophilic FeOB from the Gallionella/Sideroxydans group (Emerson et al., 2010). Other abundant FeOB-related phylotypes included ones very similar to Fe(II)-oxidizing denitrifying bacteria from the genus Aquabacterium (Buchholz-Cleven et al., 1997), and ones closely related to the microaerophilic Fe(II)-oxidizing Comamonas strain IST-3 (Blöthe and Roden, 2009). Both libraries also included sequences related to known Fe(III)-reducing organisms, including Rhodoferax at site 2, and Desulfovibrio, Aeromonas, and Geobacter at site 7. Although Desulfovibrio is typically known as a sulfate-reducing bacterium, various strains from this genus are known to be capable of coupling organics or H2 oxidation to Fe(III) reduction (Coleman et al., 1993; Lovley et al., 1993). Aeromonas is a facultative anaerobe capable of reducing Fe(III) in complex medium (Knight and Blakemore, 1998), whereas Rhodoferax and Geobacter are well known organic acid oxidizing FeRB (Lovley et al., 2004). Other sequences present in the libraries were similar to lithotrophic reduced sulfur (Sulfuricella, Ottowia) and methane (Methylobacter, Methylosarcina, Methylomonas) oxidizing organisms, as well as aerobic and anaerobic heterotrophs.

Barcode sequencing

High throughput barcode sequencing was applied to the same DNA extracts used to construct the clone libraries, resulting in (1) 2400–3000 V4 region sequences and 15,000–16,000 V6 region sequences on the Roche 454 platform; and (2) 20,000–50,000 V1 region sequences and 35,000–120,000 V4 region sequences on the Illumina platform. There was good, though not perfect, overlap among taxa in the different barcode libraries at the phylum level, and at the class level within the Proteobacteria (Figure 7). There was also general agreement between the composition of the conventional clone and barcode libraries at these levels of phylogenetic resolution.

Similar relative abundances of Betaproteobacteria sequences within the order Burkholderiales were recorded in all four barcode libraries for the mat and puffball materials (Tables 4 and 5), confirming the predominance of these taxa indicated by the clone library results. The significant number of Desulfovibrionales within the Deltaproteobacteria in the puffball clone library was also reflected in each of the barcode libraries. Beyond these overlaps, no broad agreement between the different barcode and the clone library results was evident for taxonomic groupings below the phylum/class level. For example, the predominance of Gallionellaceae in the clone libraries was not evident in the barcode libraries. In addition, Firmicutes from the class Bacilli were well-represented in all mat barcode libraries, but were completely absent from the corresponding clone library. In contrast, Bacilli and other Firmicutes were fairly well-represented (10% of total) in the clone library for the puffball, but were completely absent from all four of the barcode libraries. The same was true for Methylococcales related sequences in the puffball, which were abundant in the clone library but absent from the barcode libraries. Finally, the significant number of Pseudomonas and Sphingobacteria related sequences in some (but not all) of the puffball barcode libraries were absent from the corresponding clone library.

Table 4.

Relative abundance (percentage of total sequences) of different phylogenetic taxa obtained conventional cloning and sequencing (Clone lib) and by pyrosequencing of 16S rRNA genes from site 2 (microbial mat) using different sequencing platforms and primer sets.

| Taxa | Percent of sequences |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clone lib | V4–454 | V6–454 | V1-Illumina | V4-Illumina | |

| Bacteria/Firmicutes | 0 | 29 | 28 | 29 | 8 |

| Bacilli | 0 | 29 | 28 | 29 | 7 |

| Bacillales | 0 | 29 | 28 | 29 | 7 |

| Sporolactobacillaceae | 0 | 0 | 28 | 0 | 0 |

| Tuberibacillus | 0 | 0 | 28 | 0 | 0 |

| Bacillaceae | 0 | 29 | 0 | 29 | 7 |

| Bacillus | 0 | 24 | 0 | 29 | 0 |

| Bacteria/Firmicutes | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bacteria/Proteobacteria | 94 | 71 | 72 | 70 | 92 |

| Betaproteobacteria | 94 | 70 | 69 | 70 | 86 |

| Burkholderiales | 38 | 67 | 63 | 62 | 76 |

| Comamonadaceae | 8 | 67 | 62 | 61 | 75 |

| Acidovorax | 0 | 59 | 2 | <1 | 0 |

| Pseudorhodoferax | 0 | 0 | 59 | 0 | 0 |

| Rhodoferax | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unclassified Comamonadaceae | 0 | 5 | 2 | 60 | 75 |

| Unclassified Burkholderiales | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Aquabacterium | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rhodocyclales | 0 | <1 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Rhodocyclaceae | 0 | <1 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Propionivibrio | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Unclassified Rhodocyclaceae | 0 | <1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Nitrosomonadales | 56 | <1 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Gallionellaceae | 56 | <1 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Gallionella | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Candidatus Nitrotoga | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sideroxydans | 7 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Unclassified Betaproteobacteria | 0 | <1 | <1 | 0 | 5 |

| Gammaproteobacteria | 0 | 1 | 3 | <1 | 5 |

| Total no. of sequences | 57 | 3076 | 15,689 | 19,747 | 119,631 |

V1, V4, and V6 refer to different variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene; 454 refers to the Roche 454 GS20 (V6) or GS FLX (V4) platform; Illumina refers to the Illumina GAIIx platform. Black, red, blue, green, and magenta text refer to Domain/Phylum, Class, Order, Family, and Genus level assignments, respectively. Taxa present at >20% abundance are shown in bold; relative abundances of <1% ranged from 0.1 to 0.99%; values of 0 correspond to <0.1%.

Table 5.

Relative abundance of different phylogenetic taxa obtained by cloning and sequencing and pyrosequencing of 16S rRNA genes from site 7 (puffball) using different sequencing platforms and primer sets.

| Taxa | Percent of sequences |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clone lib | V4–454 | V6–454 | V1-Illumina | V4-Illumina | |

| Bacteria/Firmicutes | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bacilli | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bacillales | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bacillaceae | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bacillus | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Clostridia | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Clostridiales | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unclassified Clostridiales | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Blautia | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bacteria/Proteobacteria | 90 | 89 | 92 | 96 | 97 |

| Alphaproteobacteria | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rhizobales | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hyphomicrobiaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rhodoplanes | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Betaproteobacteria | 48 | 29 | 37 | 45 | 36 |

| Burkholderiales | 20 | 26 | 31 | 32 | 22 |

| Comamonadaceae | 12 | 23 | 28 | 31 | 19 |

| Comamonas | 11 | 20 | 21 | 0 | 17 |

| Hylemonella | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pseudorhodoferax | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Unclassified Comamonadaceae | 0 | 2 | 2 | 31 | 2 |

| Unclassified Burkholderiales | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Aquabacterium | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Methylophilales | 0 | <1 | <1 | 3 | 3 |

| Methylophilaceae | 0 | <1 | <1 | 3 | 3 |

| Methylophilus | 0 | <1 | <1 | 3 | 3 |

| Nitrosomonadales | 16 | <1 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Gallionellaceae | 16 | <1 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Gallionella | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sideroxydans | 15 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Rhodocyclales | 12 | <1 | <1 | 6 | 5 |

| Rhodocyclaceae | 15 | <1 | <1 | 6 | 5 |

| Propionivibrio | 7 | <1 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Rhodocyclus | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unclassified Rhodocyclaceae | 0 | <1 | <1 | 0 | 5 |

| Unclassified Rhodocyclales | 0 | 2 | <1 | 5 | 5 |

| Deltaproteobacteria | 14 | 31 | 14 | 31 | 23 |

| Desulfovibrionales | 10 | 31 | 14 | 0 | 23 |

| Desulfovibrionaceae | 10 | 31 | 14 | 0 | 23 |

| Desulfovibrio | 10 | 31 | 14 | 0 | 23 |

| Desulfuromonodales | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Geobacteraceae | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Geobacter | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unclassified Deltaproteobacteria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 0 |

| Gammaproteobacteria | 27 | 29 | 35 | 18 | 33 |

| Aeromonadales | 9 | 5 | <1 | <1 | 6 |

| Aeromonadaceae | 9 | 5 | <1 | <1 | 6 |

| Aeromonas | 9 | 5 | <1 | <1 | 6 |

| Alteromonadales | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Alteromonadaceae | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Marinobacter | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Methylococcales | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Crenotrichaceae | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Crenothrix | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Methylococcaceae | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Methylobacter | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Methylosarcina | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pseudomonadales | 0 | 23 | 3 | 17 | 25 |

| Pseudomonadaceae | 0 | 23 | <1 | 17 | 23 |

| Pseudomonas | 0 | 22 | <1 | 17 | 13 |

| Unclassified Pseudomonadaceae | 0 | <1 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Xanthomonadales | 0 | <1 | 12 | <1 | <1 |

| Xanthomonadaceae | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | <1 |

| Dyella | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| Unclassified Xanthomonadales | 0 | <1 | 12 | <1 | 2 |

| Unclassified Proteobacteria | 0 | <1 | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| Bacteria/Bacteroidetes | 0 | 10 | <1 | <1 | 1 |

| Sphingobacteria | 0 | 10 | <1 | 0 | <1 |

| Sphingobacteriales | 0 | 10 | <1 | 0 | <1 |

| Unclassified Sphingobacteriales | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | <1 |

| Unclassified Sphingobacteria | 0 | <1 | 0 | <1 | <1 |

| Unclassified Bacteria | 0 | 0 | 7 | 3 | <1 |

| Total no. of sequences | 80 | 2385 | 15,573 | 50,093 | 35,512 |

See Table 2 caption for details.

Discussion

Geochemical elucidation of an extant microbial ferrous wheel

The voltammetric microelectrode measurements provided evidence of Fe redox cycling in both the mat and puffball materials. The steep opposing gradients of Fe(II) and O2 are analogous to those documented previously in circumneutral Fe seep and freshwater sedimentary environments (Emerson and Revsbech, 1994b; Sobolev and Roden, 2002; Druschel et al., 2008; Bruun et al., 2010), as well as in situ gradients in Fe rich microbial mats at the Loihi Seamount (Glazer and Rouxel, 2009). These conditions provide an ideal situation for coupled Fe oxidation and reduction, with poorly crystalline Fe(III) oxides generated during Fe(II) oxidation serving as excellent electron acceptors for FeRB (Straub et al., 1998; Roden et al., 2004; Blöthe and Roden, 2009). In addition, soluble or complexed Fe(III) (or very small colloidal phases) formed during Fe(II) oxidation (cf. Sobolev and Roden, 2001) also represents an ideal electron acceptor for FeRB, and it is notable in this regard that almost all of the sampling sites showed the presence of Fe(III) detectable by voltammetry (Table 1).

This study did not include determination of the kinetics of Fe(II) oxidation or the contribution of microbial activity to this process. Stirred reactor studies with FeOB pure cultures (Neubauer et al., 2002; Druschel et al., 2008) and native groundwater seep microorganisms (Emerson and Revsbech, 1994a; Rentz et al., 2007) have shown that FeOB activity can accelerate Fe(II) oxidation rates two to fivefold, although competition with abiotic oxidation [including catalysis of abiotic oxidation by amorphous Fe(III) oxide surfaces] is high at neutral pH. Druschel et al. (2008) showed that the relative contribution of microbial activity to Fe(II) oxidation was greatest at O2 concentrations of less than ca. 50 μM (ca. 18% saturation), whereas biotic and abiotic rates were identical at full O2 saturation (275 μM). Experiments employing diffusion probes in Fe(II)-O2 opposing gradient cultures have indicated that microbial activity can account for ≥90% of Fe(II) oxidation under diffusive transport limited conditions (Sobolev and Roden, 2001; Roden et al., 2004) where O2 concentrations within the zone of Fe(II)-O2 reaction are typically ca. 20% saturation.

The quiescent conditions (no visible water movement or turbulent mixing) at both the mat and puffball sites suggest that Fe(II)-O2 interactions were likely diffusion limited at the time of sampling. The mat, which was overlain by only a thin layer of water (<1 cm; see Figure 3), showed a relatively compact gradient system only a few mm in spatial extent (Figure 4A). The observed Fe(II) and O2 gradients were similar to those in opposing gradient FeOB culture systems in which microbial catalysis dominates Fe(II) oxidation (Sobolev and Roden, 2001), as well as those in diffusion controlled FeOB–FeRB coculture experiments where active Fe redox cycling has been documented (Sobolev and Roden, 2002; Roden et al., 2004).

In contrast, the puffball site, where the water depth was ca. 10 cm, represented a different, less compact type of diffusion limited Fe(II)-O2 reaction system. Here, low O2 conditions (<3 μM) were achieved within a mm of the water surface (Figure 4B), analogous to other “open water” (i.e., not mat colonized) locations in the seep, where O2 was undetected just below the water surface and dissolved Fe(II) concentrations were 300–400 μM (Table 1). These observations suggest the possibility that the puffballs may originate from conglomerates of bacterial cells and oxides that form at the air–water interface and later coagulate and sink in globular form. Working a few years earlier with samples from the same environment, Schieber and Glamoclija (2007) showed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) that mat materials are composed of nanometer-sized amorphous Fe(III) oxide particles coordinated with bacterial cells (including stalk and sheath-forming FeOB similar to those shown in Figure 2) and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). In the case of well-consolidated mats, these materials were arranged in a columnar, honeycomb-like matrix. It seems possible that similar structures were present in the puffball materials, although it is not possible to image such structures via SEM as they lose their integrity during sampling. One would expect that such structures, assembled near the water surface, would eventually sink under their own weight, leading to the observed accumulation of fluffy precipitates at depth in the water column.

An alternative explanation for puffball formation is that low levels of dissolved O2 (below the detection limit in this study) do in fact exist deeper in the water column, leading to Fe(II) oxidation and oxide accumulation at depth. This explanation is consistent with the observation (Schieber, unpublished) that under conditions of water column stagnation, the puffballs appear to form at depth and grow upwards until they intercept the surface. The presence of submicromolar levels of dissolved O2 at depths below the macroscopic O2 gradient has been documented in oxygen-minimum-zones in the ocean (Revsbech et al., 2009; Canfield et al., 2010) and in the permanently stratified Black Sea water column (Clement et al., 2009). In the case of the Black Sea, indigenous aerobic bacteria were shown to be capable of efficient oxidation of dissolved Mn(II) at O2 concentrations well below 1 μM (Clement et al., 2009). It is logical to assume that aerobic FeOB share this same ability, although detailed information on the kinetics of enzymatic Fe(II) oxidation at very low O2 concentration is not available. Nitrate-dependent Fe(II) oxidation could also contribute to Fe(III) oxide accumulation at depth in the stagnant water column. The presence of dissolved, presumably organic complexed Fe(III) (Taillefert et al., 2000) at depths below which O2 could be detected (Table 1; Figure 4) is consistent with ongoing Fe(II) oxidation under very low O2 or anoxic conditions.

The association of Fe(III) oxides with organic materials and their accumulation in the semi-consolidated mat and puffball structures provides an explanation for Fe(III) reduction activity observed in the Fe(III) reduction experiments (Figure 5), with senescent FeOB and other bacterial cells and organics (e.g., originating from the surrounding forest soils) providing the electron donors for Fe(III) reduction. At the puffball site in particular, decomposition of organics coupled to Fe(III) oxide reduction can account for the abrupt increase in Fe(II) concentration within the puffball compared to the overlying water (Figure 4B). The fact that Fe(III) oxide reduction commenced immediately (no lag period) during anoxic incubation of these materials is consistent with the presence of ongoing FeRB activity. Incomplete (25–35%) Fe(III) oxide reduction was observed in both the mat and puffball incubations, in contrast to previous studies with electron donor (acetate/lactate) amended seep materials (not conducted in this study) in which near complete (≥80%) reduction has been documented (Emerson and Revsbech, 1994b; Blöthe and Roden, 2009). These results suggest that Fe(III) reduction was carbon-limited, which makes sense given that large quantities of Fe(III) oxide accumulate in the seep environment. Nevertheless, simple kinetic calculations indicate that partial Fe(II) regeneration via decomposition of organic carbon coupled to Fe(III) reduction has the potential to significantly promote Fe turnover in redox interfacial environments (Blöthe and Roden, 2009). Collectively, the results of this and a limited number of related studies in Fe seeps (Blöthe and Roden, 2009; Bruun et al., 2010), freshwater wetland surface sediments (Sobolev and Roden, 2002), and plant rhizosphere sediments (Weiss et al., 2003, 2005) provide plausible real-world examples of the type of closely coupled microbial Fe redox cycle documented previously for cocultures of aerobic FeOB and FeRB (Sobolev and Roden, 2002; Roden et al., 2004).

Microbiological evidence for in situ microbial Fe redox cycling

Significant numbers of culturable FeOB and FeRB were present in both the mat and puffball materials (Table 2). However, the observed FeOB and FeRB densities were generally <1% of total culturable aerobic and fermentative heterotrophs, comparable to results obtained in other studies in which active microbial Fe redox cycling was implicated (Weiss et al., 2003; Blöthe and Roden, 2009). To our knowledge the efficiency of conventional FeOB and FeRB culturing approaches compared to heterotrophs has not been documented, and the possibility exists that the former populations were underestimated in this and other studies, due to culturability issues. This assertion is supported by the clone library results, which provided strong support for a lithotroph-dominated microbial community centered around taxa related to known FeOB (Table 3). Sequences related at the species level (≥97% similarity in 16S rRNA gene sequence) to microaerophilic FeOB Gallionella capsiferriformans ES-2 and Sideroxydans lithotrophicus ES-1 (Emerson and Moyer, 1997) were the most abundant taxa in the mat and puffball libraries, respectively. In addition, both libraries contained significant numbers of sequences closely related (99%) to denitrifying FeOB previously identified in freshwater sediments (Buchholz-Cleven et al., 1997), many of which are known to be capable of microaerophilic Fe(II) oxidation (Benz et al., 1998). The puffball library also contained sequences identical to the microaerophilic FeOB Comomonas sp. IST-3 isolated from a groundwater Fe seep in Alabama (Blöthe and Roden, 2009). Other putative lithotrophs were identified, including sequences related (albeit distantly at 92%) to the reduced sulfur (S0 and ) oxidizing Sulfuricella denitrificans in the mat, and to the CH4 oxidizing Methylobacter sp. in the puffball. Whether or not sulfur or methane oxidation takes place in the seep is unknown.

The clone libraries also contained significant numbers of sequences related to known FeRB, including Rhodoferax ferrireducens (Finneran et al., 2003) in the mat, and Aeromonas hydrophila (Knight and Blakemore, 1998) and Geobacter sp. (Lovley et al., 2004) in the puffball. The puffball library also contained sequences related to Desulfovibrio, a sulfate-reducing taxon which includes organisms capable of dissimilatory reduction of Fe(III) and other oxidized metals (Coleman et al., 1993; Lovley et al., 1993). Collectively, sequences related to known FeOB and FeRB accounted for 88 and 59% of total sequences in the mat and puffball libraries, respectively. These results confirm 16S rRNA gene clone library results for analogous groundwater seep environments (Haaijer et al., 2008; Blöthe and Roden, 2009; Duckworth et al., 2009; Bruun et al., 2010; Fleming et al., 2011; Gault et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2012), and are consistent with the presence of active Fe redox cycling microbial communities in such environments.

Barcode sequencing of 16S rRNA gene amplicons

The specialized environment of the groundwater Fe seep provided an opportunity to assess whether high throughput barcode sequencing approaches can provide increased insight into 16S rRNA gene-based inferences of microbial community structure and functionality compared to those obtained through conventional cloning and sequencing. The motivation for applying these approaches is that they afford the opportunity to obtain 100–1000 times more sequences compared to a typical clone library consisting of a few hundred clones or less. Acquiring a much greater number of sequences has the potential to both extend knowledge of microbial diversity as well as more confidently reveal the dominant components of a given community (Sogin et al., 2006; Huber et al., 2007; Cardenas and Tiedje, 2008). The latter consideration is most relevant to this study, given our focus on dissection of a representative Fe redox cycling microbial community.

The barcode sequencing results agreed well with the conventional clone libraries at the phylum/class level (Figure 7). In particular, the relative importance of Betaproteobacteria in both the mat and puffball materials indicated by the clone libraries was verified by the barcode sequencing. This result is in agreement with a combined clone library and V4–454 sequencing study of a groundwater Fe seep in Maine (Fleming et al., 2011). However, in contrast to the findings of Fleming et al. (2011), where the Leptothrix dominated FeOB community indicated by clone library composition was verified by barcode sequencing, the Gallionella/Sideroxydans dominated FeOB communities suggested by the mat and puffball clone libraries was only verified by the V6 barcode libraries, and was not observed in the other libraries (see Tables 4 and 5). Even in the case of the V6 libraries, the relative abundance of Gallionella/Sideroxydans sequences was considerably lower than that observed in the clone libraries (5 vs. 47% for the mat, 5 vs. 16% for the puffball). While the cause for this mismatch remains unknown, it must be acknowledged that current barcode sequencing approaches, like conventional cloning and sequencing (von Wintzingerode et al., 1997), is subject to various types of biases (including PCR bias) that may render accurate quantitative analysis of microbial community structure difficult or impossible (Berry et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2011). This limitation provides a plausible (albeit disappointing) explanation for various other mismatches between the clone library and barcode sequencing results, as well as differences in community composition among the different barcode libraries (see Results). Additional comparisons of conventional cloning and barcode sequencing approaches will be required to evaluate whether or not these methodologies routinely provide a common picture of microbial community composition.

Despite the apparent limited overlap among taxa present in the clone and barcode libraries, the barcode sequence information could nevertheless be used to gain further insight into characteristics of the mat and puffball microbial communities. A series of BLAST searches was conducted with most abundant OTUs (≥0.5% of total sequences) detected in the barcode libraries; only the V4–454 sequences were used for this analysis, as these reads were 3–4 times longer than the V6–454 and Illumina sequences, thereby affording greater phylogenetic resolution (BLAST analysis of the shorter reads revealed large numbers of high similarity hits that could not be rationally distinguished in terms of their ability to provide insight in Fe redox cycling components of the microbial community). The similarity between the V4–454 and clone library OTUs was determined in conjunction with this analysis. Several interesting results emerged (see Tables 6 and 7). First, many of the most abundant V4–454 OTUs were highly similar to known FeOB, including Acidovorax sequences closely related to the denitrifying FeOB A. delafieldii 2AN (Chakraborty et al., 2011) for the microbial mat; and Comomonas sequences related the aerobic FeOB Comomonas sp. IST-3 (Blöthe and Roden, 2009) together with Aquabacterium and Pseudomonas sequences closely related to denitrifying FeOB (Straub et al., 1996; Buchholz-Cleven et al., 1997; Muehe et al., 2009) for the puffball. The seep contains significant nitrate (ca. 0.02–0.2 mM), and active nitrate-reducing, Fe(II)-oxidizing enrichment cultures were obtained from both the mat and puffball materials (M. Blöthe, unpublished data). In addition, a nitrate-reducing, Fe(II)-oxidizing Dechlorospirillum species (unrelated to sequences reported here) was recently isolated from the seep materials (Picardal et al., 2011). It is unknown whether or not A. delafieldii 2AN or the nitrate-dependent FeOB described by Buchholz-Cleven et al. (1997) are capable of microaerophilic Fe(II) oxidation, but the fact that many such organisms are known to grow lithotrophically via Fe(II) oxidation under microaerophilic conditions (Benz et al., 1998) suggests that this could be the case.

Table 6.

BLAST matches to dominant (≥0.5% of total sequences) microbial mat (site 2) V4-454 sequences, and similarity between V4 454 and clone library sequences.

| Abundance rank | % Total sequences | Cumulative % total | V4 amplicon RDP assignment | Relevant BLAST match | Acession No. | Similarity (%) | Physiology | Reference(s) | Clone library RDP assignment(s) | Similarity (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 56.32 | 56.3 | Acidovorax | Acidovorax delafieldii strain 2AN | HM625980.1 | 100 | Fe(II) Ox, red | Chakraborty et al. (2011) | Rhodoferax | 97.92 |

| Aquabacterium | 97.52 | |||||||||

| 2 | 23.90 | 80.2 | Bacillus | Bacillus thioparus strain BMP-1 | DQ371431 | 100 | Ox, O2 red | Pérez-Ibarra et al. (2007) | No match | NAb |

| 3 | 2.30 | 82.5 | Unclassified Bacillaceae | Bacillus thioparus strain BMP-1 | DQ371431 | 100 | Ox, O2 red | Pérez-Ibarra et al. (2007) | No match | NA |

| 4 | 0.81 | 83.3 | Unclassified Comamonadaceae | Acidovorax delafieldii strain 2AN | HM625980.1 | 97 | Fe(II) Ox, red | Chakraborty et al. (2011) | Rhodoferax | 95.02 |

| Aquabacterium | 94.67 | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.81 | 84.1 | Unclassified Comamonadaceae | Acidovorax delafieldii strain 2AN | HM625980.1 | 97 | Fe(II) Ox, red | Chakraborty et al. (2011) | Rhodoferax | 97.84 |

| Aquabacterium | 97.42 | |||||||||

| 6 | 0.75 | 84.9 | Acidovorax | Acidovorax delafieldii strain 2AN | HM625980.1 | 97 | Fe(II) Ox, red | Chakraborty et al. (2011) | Aquabacterium | 97.53 |

| Rhodoferax | 97.12 | |||||||||

| 7 | 0.52 | 85.4 | Stenotrophomonas | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia strain CCUG 41684 | GU945534.1 | 100 | Aerobic heterotroph | Svensson-Stadler et al. (2012) | No match | NA |

aDetermined by querying each V4 454 sequence against the full set of unique clone library sequences using the “Align two or more sequences” facility in BLAST; only matches with ca. 95% or greater similary are reported.

bNot applicable.

Table 7.

BLAST matches to dominant (≥0.5% of total sequences) puffball (site 7) V4–454 sequences, and similarity between V4 454 and clone library sequences.

| Abundance rank | % Total sequences | Cumulative % Total | V4 Amplicon RDP assignment | Relevant BLAST match | Acession No. | Similarity (%) | Physiology | Reference(s) | Clone library RDP assignment(s) | Similarity (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28.88 | 28.9 | Desulfovibrio | Desulfovibrio putealis strain B7-43 | NR_029118.1 | 99 | red, Fe(III) red? | Basso et al. (2005), Lovley et al. (1993) | Desulfovibrio | 99.10 |

| 2 | 16.73 | 45.6 | Comamonas | Comamonas sp. IST-3 | DQ386262.1 | 99 | Fe(II) Ox, O2 red | Blöthe and Roden (2009) | Comamonas | 99.57 |

| 3 | 9.67 | 55.3 | Unclassified Sphingobacteriales | Pontibacter korlensis strain AsK09 | GQ503321.1 | 87 | Aerobic heterotroph | Zhang et al. (2008) | No match | NAb |

| 4 | 6.94 | 62.2 | Pseudomonas | Pseudomonas alcaligenes, various strains | 100 | Aerobic heterotroph | Straub et al. (1996), Muehe et al. (2009) | No match | NA | |

| 5 | 4.54 | 66.8 | Pseudomonas | Pseudomonas stutzeri, various strains | 100 | Fe(II) Ox, red | Straub et al. (1996), Muehe et al. (2009) | No match | NA | |

| 6 | 4.33 | 71.1 | Aeromonas | Aeromonas hydrophila strain ATCC 7966 | X60404.2 | 100 | Fe(III) red | Knight and Blakemore (1998) | Aeromonas | 100 |

| 7 | 2.90 | 74.0 | Pseudomonas | Pseudomonas, various species | 100 | Aerobic heterotroph | Bergey’s (2005) | No match | NA | |

| 8 | 1.43 | 75.4 | Aquabacterium | Denitrifying Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria | U51102.1 | 99 | Fe(II) Ox, red | Buchholz-Cleven et al. (1997) | Aquabacterium | 100 |

| 9 | 1.18 | 76.6 | Pseudomonas | Pseudomonas, various species | 100 | Aerobic heterotroph | Bergey’s (2005) | No match | NA | |

| 10 | 1.05 | 77.6 | Pseudomonas | Pseudomonas alcaligenes, various strains | 99 | Aerobic heterotroph | Bergey’s (2005) | No match | NA | |

| 11 | 0.84 | 78.5 | Comamonas | Comamonas sp. IST-3 | DQ386262.1 | 98 | Fe(II) Ox, O2 red | Blöthe and Roden (2009) | Comamonas Aquabacterium | 98.29 97.86 |

| 12 | 0.59 | 79.1 | Pseudomonas | Pseudomonas alcaligenes, various strains | 100 | Aerobic heterotroph | Bergey’s (2005) | No match | NA | |

| 13 | 0.55 | 79.6 | Unclassified Burkholderiales | Comamonas sp. IST-3 | DQ386262.1 | 98 | Fe(II) Ox, O2 red | Blöthe and Roden (2009) | Comamonas Aquabacterium | 97.87 97.45 |

aDetermined by querying each V4 454 sequence against the full set of unique clone library sequences using the “Align two or more sequences” facility in BLAST; only matches with ca. 95% or greater similarly are reported.

bNot applicable.

Second, potential Fe(III)-reducing Desulfovibrio sequences (see previous section) closely related to D. putealis (Basso et al., 2005) were the most abundant OTUs in the puffball V4–454 libraries. This result is important in that it strongly suggests the proliferation of anaerobic bacteria within the puffball, which in turn is consistent with the geochemical measurements and in vitro Fe(III) reduction experiments (see above). We found no voltammetric evidence for the existence of dissolved sulfide in the seep waters, and the solid-phases present were uniformly orangish-brown with no evidence of black iron monosulfides. In addition, there was no production of a sulfide smell upon acidification of samples from the anaerobic incubations. Together these results indicate that the Desulfovibrio-related taxa present in the puffball materials could have been functioning as Fe(III) reducers. The apparent absence of sulfate reduction activity is consistent with the recent groundwater seep study of Bruun et al. (2010) where no significant sulfate reduction was observed during anaerobic incubation of seep materials without added electron donor.

In both of the above examples, the most abundant barcodes for Betaproteobacteria (Acidovorax, Comomonas, Aquabacterium) and Deltaproteobacteria (Desulfovibrio) related sequences were ≥97% similar to one or more unique OTUs in the clone libraries. These connections suggest that barcode sequencing did in fact sample many of the key putative Fe redox cycling taxa present in the clone libraries, even though this fact was not necessarily evident from the RDP-based phylogenetic assignments. This phenomenon is best illustrated by the Acidovorax related sequences identified in the mat V4–454 library, which were 97–98% similar to Rhodoferax and Aquabacterium related sequences from the clone libraries. A general implication of these results is that detailed BLAST searching, as well as inquiries into the physiological properties of related taxa, will likely be required to make the best possible physiological inferences from barcode sequencing information.

Another interesting finding from the V4–454 BLAST searches is that the large number of Bacillaceae related sequences in the mat library were closely related to Bacillus thioparans BMP-1, an organism capable of chemolithoautotrophic growth coupled to thiosulfate () oxidation (Pérez-Ibarra et al., 2007). Although we do not know if oxidation takes place in the seep, the large number of sequences related to this taxon clearly suggests the possibility. This may not be a far-fetched suggestion, given that oxidative dissolution of authigenic iron sulfide minerals in Mississippian-age marine sediments provides the Fe(II) source for the seep (Schieber and Glamoclija, 2007). This result, as well as the recovery of numerous sequences related to putative nitrate-reducing FeOB, provides an example of how 16S rRNA gene surveys could motivate more detailed studies of metabolically unique (in this case lithotrophic) organisms in a given microbial community.

Conclusion

A combination of geochemical and microbiological data revealed the existence of an in situ “microbial ferrous wheel” in a circumneutral groundwater Fe seep. The wheel turns by virtue of the coupled activities of lithotrophic (aerobic and possibly nitrate-reducing) FeOB and dissimilatory FeRB across mm-to-cm scale redox gradients within semi-consolidated mat and floating puffball structures. The results confirm and extend previous findings in similar groundwater Fe seep and aquatic sedimentary environments, and provide a real-world example of a microbially driven Fe redox cycling system analogous to that documented previously for cocultures of FeOB and FeRB. The groundwater seep environment also provides useful clues as to the likely physical and metabolic arrangement of microbial Fe redox cycling communities within redox gradients in a wide variety of soil and sedimentary environments.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Mitch Sogin and colleagues at MBL, and Noah Fierer and colleagues at the University of Colorado–Boulder, for facilitating the barcode sequencing of our 16S rRNA gene samples. This work was supported by the NASA Astrobiology Institute (University of California, Berkeley and University of Wisconsin–Madison nodes), and the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, Subsurface Biogeochemical Research Program through the SBR Scientific Focus Area at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Work in the Emerson laboratory at Bigelow was also supported by grants from the Office of Naval Research N00014-08-1-0334 and the National Science Foundation IOS-0951077.

References

- Achenbach L. A., Coates J. D. (2000). Disparity between bacterial phylogeny and physiology. ASM News 66, 1–4 [Google Scholar]

- Ashelford K. E., Chuzhanova N. A., Fry J. C., Jones A. J., Weightman A. J. (2005). At least 1 in 20 16S rRNA sequence records currently held in public repositories is estimated to contain substantial anomalies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 7724–7736 10.1128/AEM.71.12.7724-7736.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso O., Caumette P., Magot M. (2005). Desulfovibrio putealis sp. nov., a novel sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from a deep subsurface aquifer. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55, 101–104 10.1099/ijs.0.63303-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates S. T., Berg-Lyons D., Caporaso J. G., Walters W. A., Knight R., Fierer N. (2011). Examining the global distribution of dominant archaeal populations in soil. ISME J. 5, 908–917 10.1038/ismej.2010.171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benz M., Brune A., Schink B. (1998). Anaerobic and aerobic oxidation of ferrous iron at neutral pH by chemoheterotrophic nitrate-reducing bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 169, 159–165 10.1007/s002030050555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergey (2005). “Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology,” in The Proteobacteria, Vol 2, 2nd Edn, eds Garrity G. M., Brenner D. J., Krieg N. R., Staley J. T. (New York: Springer; ), 2816 [Google Scholar]

- Berry D., Ben Mahfoudh K., Wagner M., Loy A. (2011). Barcoded primers used in multiplex amplicon pyrosequencing bias amplification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 7846–7849 10.1128/AEM.05220-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blöthe M., Roden E. E. (2009). Microbial iron redox cycling in a circumneutral-pH groundwater seep. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 468–473 10.1128/AEM.01742-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendel P. J., Luther G. W. (1995). Development of a gold amalgam voltammetric microelectrode for the determination of dissolved Fe, Mn, O-2, and S(-II) in porewaters of marine and freshwater sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 29, 751–761 10.1021/es00003a024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brune A., Ludwig W., Schink B. (2002). Propionivibrio limicola sp. nov., a fermentative bacterium specialized in the degradation of hydroaromatic compounds, reclassification of Propionibacter pelophilus as Propionivibrio pelophilus comb. nov. and amended description of the genus Propionivibrio. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52, 441–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruun A. M., Finster K., Gunnlaugsson H. P., Nornberg P., Friedrich M. W. (2010). A comprehensive investigation on iron cycling in a freshwater seep including microscopy, cultivation and molecular community analysis. Geomicrobiol. J. 27, 15–34 10.1080/01490450903232165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz-Cleven B. E. E., Rattunde B., Straub K. L. (1997). Screening for genetic diversity of isolates of anaerobic Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria using DGGE and whole-cell hybridization. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 20, 301–309 10.1016/S0723-2020(97)80077-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield D. E., Stewart F. J., Thamdrup B., De Brabandere L., Dalsgaard T., Delong E. F., Revsbech N. P., Ulloa O. (2010). A cryptic sulfur cycle in oxygen-minimum-zone waters off the Chilean coast. Science 330, 1375–1378 10.1126/science.1196889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J. G., Lauber C. L., Walters W. A., Berg-Lyons D., Lozupone C. A., Turnbaugh P. J., Fierer N., Knight R. (2010). Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 4516–4522 10.1073/pnas.1000080107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas E., Tiedje J. M. (2008). New tools for discovering and characterizing microbial diversity. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 19, 544–549 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty A., Roden E. E., Schieber J., Picardal F. (2011). Enhanced growth of Acidovorax sp. strain 2AN during nitrate-dependent Fe(II) oxidation in batch and continuous-flow systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 8548–8556 10.1128/AEM.06214-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement B. G., Luther G. W., Tebo B. M. (2009). Rapid, oxygen-dependent microbial Mn(II) oxidation kinetics at sub-micromolar oxygen concentrations in the Black Sea suboxic zone. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 1878–1889 10.1016/j.gca.2008.12.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coby A. J., Picardal F., Shelobolina E., Xu H., Roden E. E. (2011). Repeated anaerobic microbial redox cycling of iron. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 6036–6042 10.1128/AEM.00276-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M. L., Hedrick D. B., Lovley D. R., White D. C., Pye K. (1993). Reduction of Fe(III) in sediments by sulphate-reducing bacteria. Nature 361, 436–438 10.1038/361436a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costello A. M., Lidstrom M. E. (1999). Molecular characterization of functional and phylogenetic genes from natural populations of methanotrophs in lake sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 5066–5074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings D. E., March A. W., Bostick B., Spring S., Caccavo F., Jr., Fendorf S., Rosenzweig R. F. (2000). Evidence for microbial Fe(III) reduction in anoxic, mining-impacted lake sediments (Lake Coeur d’Alene, Idaho). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 154–162 10.1128/AEM.66.1.154-162.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decho A. W., Norman R. S., Visscher P. T. (2010). Quorum sensing in natural environments: emerging views from microbial mats. Trends Microbiol. 18, 73–80 10.1016/j.tim.2009.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewhirst F. E., Chien C.-C., Paster B. J., Ericson R. L., Orcutt R. P., Schauer D. B., Fox J. G. (1999). Phylogeny of the defined murine microbiota: altered schaedler flora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 3287–3292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druschel G. K., Emerson D., Sutka R., Suchecki P., Luther G. W. (2008). Low-oxygen and chemical kinetic constraints on the geochemical niche of neutrophilic iron(II) oxidizing microorganisms. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72, 3358–3370 10.1016/j.gca.2008.04.035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth O. W., Holmström S. J. M., Peña J., Sposito G. (2009). Biogeochemistry of iron oxidation in a circumneutral freshwater habitat. Chem. Geol. 260, 149–158 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2008.08.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C., Haas B. J., Clemente J. C., Quince C., Knight R. (2011). UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27, 2194–2200 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson D. (2009). Potential for iron-reduction and iron-cycling in iron oxyhydroxide-rich microbial mats at Loihi Seamount. Geomicrobiol. J. 26, 639–647 10.1080/01490450903269985 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson D., Fleming E. J., McBeth J. M. (2010). Iron-oxidizing bacteria: an environmental and genomic perspective. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64, 561–583 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson D., Moyer C. (1997). Isolation and characterization of novel iron-oxidizing bacteria that grow at circumneutral pH. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 4784–4792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson D., Revsbech N. P. (1994a). Investigation of an iron-oxidizing microbial mat community located near Aarhus, Denmark – laboratory studies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 4032–4038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson D., Revsbech N. P. (1994b). Investigation of an iron-oxidizing microbial mat community located near Aarhus, Denmark: field studies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 4022–4031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson D., Weiss J. V., Megonigal J. P. (1999). Iron-oxidizing bacteria are associated with ferric hydroxide precipitates (Fe-plaque) on the roots of wetland plants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 2758–2761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finneran K. T., Johnsen C. V., Lovley D. R. (2003). Rhodoferax ferrireducens sp. nov., a psychrotolerant, facultatively anaerobic bacterium that oxidizes acetate with the reduction of Fe(III). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53, 669–673 10.1099/ijs.0.02298-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming E. J., Langdon A. E., Martinez-Garcia M., Stepanauskas R., Poulton N. J., Masland E. D. P., Emerson D. (2011). What’s new is old: resolving the identity of Leptothrix ochracea using single cell genomics, pyrosequencing and FISH. PLoS ONE 6, e17769. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis C. A., Tebo B. M. (2002). Enzymatic manganese(II) oxidation by metabolically dormant spores of diverse Bacillus species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 874–880 10.1128/AEM.68.2.874-880.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gault A. G., Ibrahim A., Langley S., Renaud R., Takahashi Y., Boothman C., Lloyd J. R., Clark I. D., Ferris F. G., Fortin D. (2011). Microbial and geochemical features suggest iron redox cycling within bacteriogenic iron oxide-rich sediments. Chem. Geol. 281, 41–51 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2010.11.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis M., Vandamme P., Devos P., Swings J., Kersters K. (2001). “Polyphasic taxonomy,” in Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, 2nd Edn, eds Boone D. R., Castenholz R. W. (New York: Springer; ), 43–48 [Google Scholar]

- Glazer B. T., Rouxel O. J. (2009). Redox speciation and distribution within diverse iron-dominated microbial habitats at Loihi Seamount. Geomicrobiol. J. 26, 606–622 10.1080/01490450903263392 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haaijer S. C. M., Harhangi H. R., Meijerink B. B., Strous M., Pol A., Smolders A. J. P., Verwegen K., Jetten M. S. M., Den Camp H. J. M. O. (2008). Bacteria associated with iron seeps in a sulfur-rich, neutral pH, freshwater ecosystem. ISME J. 2, 1231–1242 10.1038/ismej.2008.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamady M., Walker J. J., Harris J. K., Gold N. J., Knight R. (2008). Error-correcting barcoded primers for pyrosequencing hundreds of samples in multiplex. Nat. Methods 5, 235–237 10.1038/nmeth.1184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaki T., Suzuki M., Fudou R., Jojima Y., Kajiura T., Tabuchi A., Sen K., Shibai H. (2005). Isolation of novel bacteria and actinomycetes using soil-extract agar medium. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 99, 485–492 10.1263/jbb.99.485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraishi A. (1994). Phylogenetic affiliations of Rhodoferax fermentans and related species of phototrophic bacteria as determined by automated 16S rDNA sequencing. Curr. Microbiol. 28, 25–29 10.1007/BF01575982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland H. D., Kasting J. F. (1992). “The environment of the Archean Earth,” in The Proterozoic Biosphere: a Multidisciplinary Study, eds Schopf J. W., Klein C. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ), 21–24 [Google Scholar]

- Huber J. A., Welch D. B. M., Morrison H. G., Huse S. M., Neal P. R., Butterfield D. A., Sogin M. L. (2007). Microbial population structures in the deep marine biosphere. Science 318, 97–100 10.1126/science.1146689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter K. S., Wang Y., Vancappellen P. (1998). Kinetic modeling of microbially-driven redox chemistry of subsurface environments: coupling transport, microbial metabolism and geochemistry. J. Hydrol. 209, 53–80 10.1016/S0022-1694(98)00157-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen R. (2007). Redox microniches in groundwater: a model study on the geometric and kinetic conditions required for concomitant Fe oxide reduction, sulfate reduction, and methanogenesis. Water Resour. Res. 43, W12S12, 11. 10.1029/2006WR005663 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- James R. E., Ferris F. G. (2004). Evidence for microbial-mediated iron oxidation at a neutrophilic groundwater spring. Chem. Geol. 212, 301–311 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2004.08.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. W., Carmichael M. J., Mcdonald W., Rose N., Pitchford J., Windelspecht M., Karatan E., Brauer S. L. (2012). Increased abundance of Gallionella spp., Leptothrix spp. and total bacteria in response to enhanced Mn and Fe concentrations in a disturbed Southern Appalachian high elevation wetland. Geomicrobiol. J. 29, 124–138 10.1080/01490451.2011.558557 [DOI] [Google Scholar]