Background: The role of oxidatively modified LDL (oxmLDL) in atherosclerotic inflammation is controversial.

Results: Endotoxin-free oxmLDL fails to enhance mononuclear phagocyte inflammatory responses but suppresses IL-1β, TNF, and IL-6 when combined with endotoxin or PamCSK4.

Conclusion: OxmLDL suppresses proinflammatory responses.

Significance: Although LDL preparations have been linked to inflammatory responses, endotoxin-free, oxidatively modified LDL inhibits monocyte Toll ligands.

Keywords: Cytokine, Cytokine Induction, Lipoprotein, Macrophages, Monocytes, Toll-like Receptors (TLR)

Abstract

Inflammation characterized by the expression and release of cytokines and chemokines is implicated in the development and progression of atherosclerosis. Oxidatively modified low density lipoproteins, central to the formation of atherosclerotic plaques, have been reported to signal through Toll-like receptors (TLRs), TLR4 and TLR2, in concert with scavenger receptors to regulate the inflammatory microenvironment in atherosclerosis. This study evaluates the role of low density lipoproteins (LDL) and oxidatively modified LDL (oxmLDL) in the expression and release of proinflammatory mediators IκBζ, IL-6, IL-1β, TNFα, and IL-8 in human monocytes and macrophages. Although standard LDL preparations induced IκBζ along with IL-6 and IL-8 production, this inflammatory effect was eliminated when LDL was isolated under endotoxin-restricted conditions. However, when added with TLR4 and TLR2 ligands, this low endotoxin preparation of oxmLDL suppressed the expression and release of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFα but surprisingly spared IL-8 production. The suppressive effect of oxmLDL was specific to monocytes as it did not inhibit LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokines in human macrophages. Thus, TLR ligand contamination of LDL/oxmLDL preparations can complicate interpretations of inflammatory responses to these modified lipoproteins. In contrast to providing a proinflammatory function, oxmLDL suppresses the expression and release of selected proinflammatory mediators.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease, characterized by the development of atherosclerotic plaques, leads to acute coronary syndromes such as unstable angina, myocardial infarction, and death due to arterial occlusion (1, 2). Increased circulating concentrations of cholesterol, transported in the blood by low density lipoproteins (LDL), are a major risk factor for coronary artery disease. The high levels of circulating cholesterol-rich LDL particles are trapped in the arterial intima and are modified by peroxides such as myeloperoxidases and lipoxygenases, reactive oxygen species, phenoxyl radicals, and peroxynitrites to generate oxidatively modified LDL (oxmLDL)2 (3). These oxmLDL particles bind to scavenger receptors on the surface of the monocytes and macrophages in the arterial intima and promote the formation of the atherosclerotic plaque.

In the macrophage, the uptake of oxmLDL is facilitated by CD36 and SR-A (4). CD36, first described as the “glycoprotein IV” observed on the surface of platelets, is the receptor for thrombospondin-1 (5). Its expression has been observed on the surface of other mammalian cell types: mononuclear phagocytes, dendritic cells, microglia, adipocytes, hepatocytes, myocytes, and epithelia. Recently, CD36 has been shown to be a key co-receptor with TLR2 for certain bacterial lipopeptides (6–8). Because CD36 recognizes oxmLDL, it has been suggested to be able to induce sterile inflammation as well (9). To investigate the direct role that LDL plays in the inflammation associated with atherosclerosis, we utilized an in vitro model to study LDL/oxmLDL recognition by human mononuclear phagocytes as an inducer of proinflammatory cytokines. We focused attention on IL-6, IL-1β, TNF, IL-8, and a new member of the IκB family (IκBζ) that has been shown to regulate a number of inflammatory cytokines and proteins of relevance to atherosclerosis (IL-6, IL-12, IL-18, GM-CSF, lipocalin-2, endothelin-1, macrophage receptor with collagenous structure (MARCO), and ghrelin) as surrogates of the early events in LDL/oxmLDL recognition (10). Our findings emphasize the importance of evaluating biological materials for endotoxin contamination when studying innate host responses and, in this context, support an unexpected role for oxmLDL as an inhibitor of inflammatory responses to pathogen-induced signals.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Antibodies

CD14 magnetic selection beads were purchased from Miltenyi Biotec. The following reagents were obtained from the following sources: RPMI 1640 (Cellgro and Invitrogen), fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals), and penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen). LPS E. coli strain 0111:B4 was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals. PamCSK4 was purchased from EMC microcollections GmbH. The actin monoclonal clone C4 was purchased from MP Biomedicals. FITC-labeled CD36 antibody and allophycocyanin-labeled CD14 antibody were purchased from eBioscience. Rabbit antiserum against IκBζ and pro-IL-1β was generated in our laboratory using recombinant protein expressed in Escherichia coli as described previously (11). The lactate dehydrogenase assay was performed using the cytotoxicity detection kit from Roche Applied Science.

Cell Culture

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by Histopaque density gradient centrifugation from fresh source leukocytes from the American Red Cross. Monocytes were isolated by CD14-positive magnetic selection. Macrophages were matured in Teflon containers by plating peripheral blood mononuclear cells (2 × 106/ml) in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 20% human AB serum for 6 days. After 6 days, the harvested cells were extensively washed, and macrophages were isolated by adherence. Monocytes (2 × 106/ml) and macrophages (1 × 106/ml) were plated in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin streptomycin. Monocytes were stimulated with LPS (100 and 10 ng/ml) or PamCSK4 (50 and 5 ng/ml) for the times indicated. Macrophages were stimulated with LPS (500 ng/ml) for the times indicated.

LDL Isolation and Oxidation

LDL was isolated from the plasma of fasting, healthy volunteer donors by sequential preparative ultracentrifugation technique using a 120.2 TL rotor in an Optima TL Beckman ultracentrifuge (Beckman Instruments) as demonstrated previously (12). LDL was dialyzed overnight into PBS at 4 °C. Protein estimation of the isolate was performed by Lowry's assay. LDL (100 μg/ml) was oxidized in the presence of Cu2+ (5 μm) at room temperature, and the oxidation was monitored overnight by measuring the A234 so as to isolate the different forms of oxidized LDL: minimally modified LDL (mmLDL ∼60–90min), oxidized LDL (oxLDL ∼3 h), and oxmLDL (∼24 h). Samples were then stored at 4 °C and used within 3 h. For the preparation of LDL low in endotoxin, the glassware was soaked in E-Toxa-Clean (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight. The glassware was washed in endotoxin-free water (HyClone), dried, and autoclaved. The preparation was performed in a tissue culture hood with precautions taken for minimal endotoxin contamination with the usage of pyrogen-free tubes and tips. For dialysis, endotoxin-free PBS (Cellgro) and γ ray sterilized dialysis cassettes (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used.

Flow Cytometry

Human monocytes (5 × 106/ml) and macrophages (7 × 106/ml) were prepared, stained with FITC-conjugated anti-human CD36 antibody or allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-human CD14 antibody, and analyzed by flow cytometry analysis as described previously (13).

Quantitative PCR

Monocytes were stimulated for the times indicated, and total RNA was extracted and converted to cDNA as described previously (14). Primers specific for IκBζ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), IL-1RII, IL-10, IL-1RN, and mannose receptor C type 1 (MRC-1) were used for analyzing mRNA expression. Gene expression was normalized to two housekeeping genes, GAPDH and CAP-1.

Preparation of Cell Lysates and Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed, and cell lysates were prepared as described previously (14). Total protein was estimated using Lowry's assay (Bio-Rad), and equal protein (10–20 μg) was loaded per lane of NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen). The separated proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes, which were blocked with 10% nonfat milk. Blocked membranes were blotted overnight at 4 °C with appropriate primary antibody followed by secondary antibody and visualization by ECL (GE Healthcare).

Limulus Amebocyte Lysate Assay

A limulus amebocyte lysate assay kit for the evaluation of endotoxin contamination in samples was purchased from Lonza. Endotoxin measurement in the samples was performed as per the manufacturer's recommendations.

ELISA

ELISA kits for IL-6 and IL-8 were purchased from eBioscience. ELISAs for IL-1β and TNFα were developed in our laboratory (15–17).

Statistical Analysis

Values are expressed either as mean ± S.E. or as mean ± S.D. Standard t test was used for all comparisons. Significance was defined as p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Monocyte Induction of IκBζ and Cytokines in Response to LDL and oxmLDL

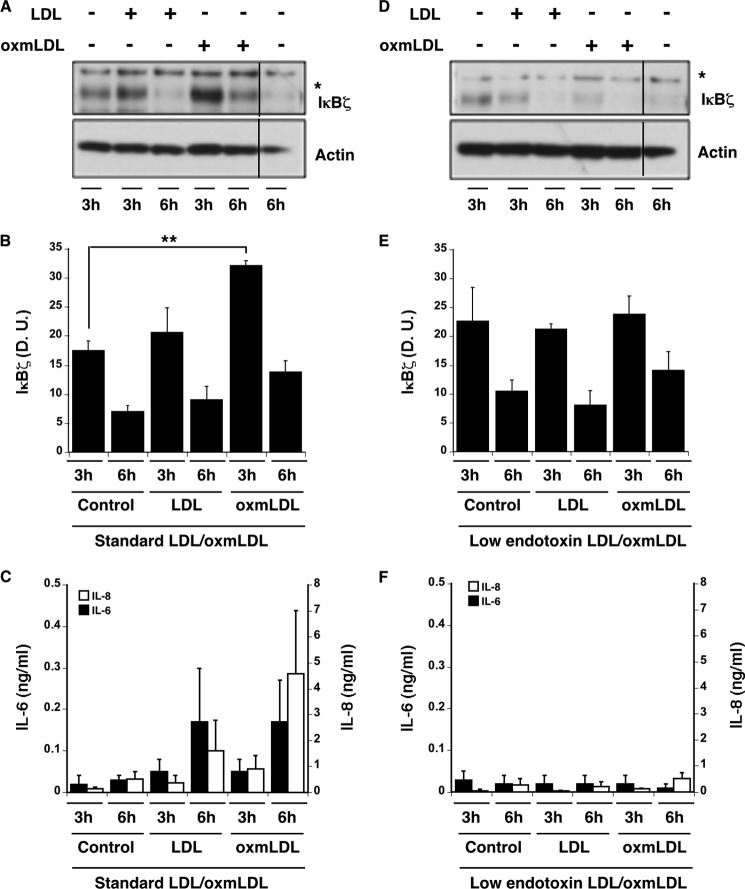

Oxidized LDL activates proinflammatory cytokines by signaling through CD36 in concert with TLR2 (6, 8). Many of these cytokines (most notably IL-6) are regulated by the IκB member, IκBζ (10). To study the effects of LDL and oxmLDL on cytokine release, native LDL was isolated and modified to oxmLDL using Cu2+ (5 μm) and then incubated with fresh human monocytes for 3 and 6 h. As expected, standard preparations of LDL and oxmLDL induced the rapid induction of IκBζ (Fig. 1, A and B). The IκBζ expression assayed by densitometry was significantly higher (p < 0.05) upon treatment with oxmLDL as compared with controls (Fig. 1B). Additionally, this enhanced IκBζ expression was also followed by increased IL-6 and IL-8 release (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Inflammatory responses in LDL- and oxmLDL-treated monocytes. LDL was isolated from human serum by the standard protocol or the low endotoxin protocol as discussed. Monocytes (2 × 106/ml) were treated with LDL or oxmLDL (25 μg/ml each) derived from the two different protocols for 3 or 6 h. A and D, IκBζ and actin immunoblots of cell lysates representative of n = 3 for the standard LDL/oxmLDL (A) or n = 3 for the low endotoxin LDL/oxmLDL (D). B and E, IκBζ densitometry (in densitometry units (D. U.)) from immunoblots in response to standard LDL/oxmLDL (n = 3) (B) or low endotoxin LDL/oxmLDL (n = 3) (E). C and F, IL-6 and IL-8 ELISA data for cell supernatants from standard (n = 4) (C) and low endotoxin preparations (n = 3) (F). Bar values show mean ± S.E. Vertical lines have been inserted to indicate repositioned gel lanes. * represents nonspecific band. ** represents p < 0.05.

Because endotoxin contamination is possible with standard LDL isolation procedures, the endotoxin level in these LDL and oxmLDL preparations was determined by limulus amebocyte lysate assay and found to be between 15 and 90 endotoxin units/ml. To attempt to discriminate between the effect of LDL and contaminating endotoxin, LDL was therefore purified to achieve low endotoxin levels (<0.125 enzyme units/ml) and incubated with monocytes for 3 and 6 h. Although background IκBζ expression was detectable (Fig. 1, D and E), stimulation with native LDL and oxmLDL did not enhance expression of IκBζ. In agreement with the absent IκBζ activation, IL-6 and IL-8 expression was not significantly induced by these preparations of native LDL and oxmLDL. (Fig. 1F). These observations suggest that the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and related proteins is not due to LDL or oxmLDL.

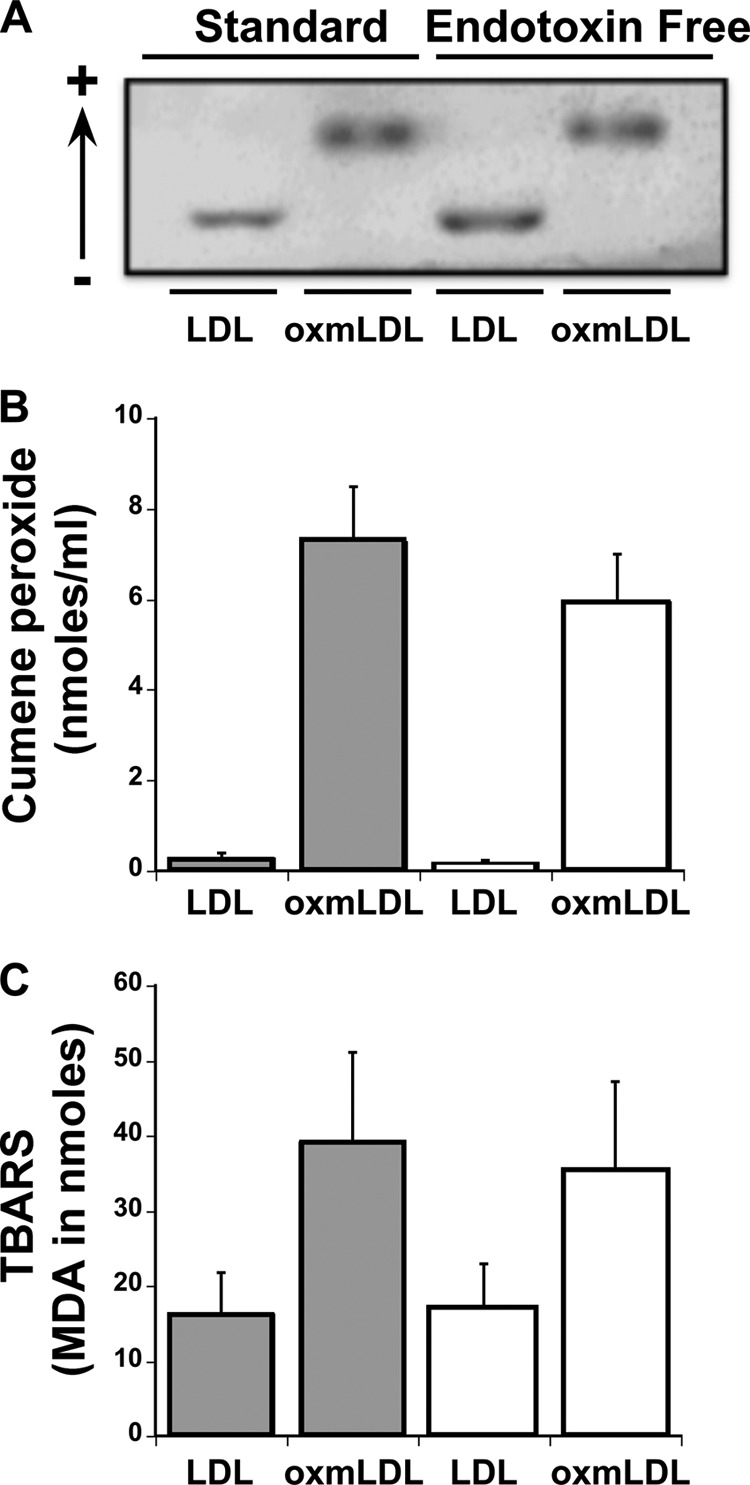

Effect of LDL Purification Procedure on Oxidative Modifications

To rule out the possibility that the purification procedure might interfere with the oxidation of LDL, we evaluated native LDL and oxmLDL prepared by the standard and the low endotoxin methods for electronegativity (a measure of oxidative modifications (3)) (Fig. 2A). As observed, the electrophoretic mobility of oxmLDL was increased in both preparations of oxmLDL, suggesting no differences in oxidative modifications. Similarly, the peroxide content between the two different preparations as determined by thiobarbituric acid reactive substances assay and cumene peroxide assay was not affected by the mode of LDL preparation (Fig. 2, B and C). Taken together these findings suggest that differences in IκBζ and cytokine expression between standard and low endotoxin LDL/oxmLDL preparations are not due to the differences in oxidative modifications.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of LDL preparation modality on oxidative modifications. LDL and oxmLDL were prepared in the standard or the stringent manner. A, samples were analyzed for their electronegative content by electrophoretic mobility. B and C, the different samples were also analyzed for the total peroxide content using the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay (B) and cumene peroxide assay (C). The electrophoretic mobility blot is representative of three independent experiments. The bar values for the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances assay are represented as mean ± S.E. for three independent experiments, and the bar values for the cumene peroxide assay are represented as mean ± S.E. for four independent experiments.

Monocyte Response to the Different Forms of Copper-oxidized LDL

Oxidation of native LDL with Cu2+ yields LDL with variable levels of oxidation, namely, mmLDL, oxLDL, and oxmLDL, that are known to migrate with different electronegativities (supplemental Fig. S1) (3). To test whether these different forms of oxidized LDL might differentially activate proinflammatory responses, monocytes were incubated with these different forms of oxidized LDL. As observed, the expression of IL-6 and IL-8 was unaffected as compared with the effect in response to LPS (positive control) (Table 1). This suggested that none of the Cu2+-oxidized LDL forms alone are able to activate significant cytokine responses in human monocytes.

TABLE 1.

Cytokine release in response to LDL and different forms of copper-oxidized LDL in human monocytes

Human monocytes (2 × 106/ml) were treated with native LDL and copper-oxidized LDL for 3 and 6 h. The cell supernatants were measured for IL-6 and IL-8 release by ELISA. Values are represented as mean ± S.E. for three independent experiments.

| Samples | IL-6 (ng/ml) |

IL-8 (ng/ml)) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 h | 6 h | 3 h | 6 h | |

| Control | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.06 ± 0.04 | 0.41 ± 0.08 | 1.04 ± 0.41 |

| Native LDL | 0.04 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 0.44 ± 0.07 | 0.86 ± 0.39 |

| Native LDL + Cu2+ (5 μm) | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.48 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.37 |

| mmLDL | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.47 ± 0.05 | 1.11 ± 0.40 |

| oxLDL | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.47 ± 0.021 | 1.35 ± 0.39 |

| oxmLDL | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.75 ± 0.34 | 1.84 ± 0.23 |

| LPS (100 ng/ml) | 3.4 ± 0.25 | 25 ± 7 | 5.7 ± 1.1 | 16 ± 1.5 |

| LPS (10 ng/ml) | 3.7 ± 0.53 | 25 ± 10 | 4.9 ± 0.9 | 16 ± 1.6 |

Monocyte Responses Suppressed by oxmLDL when Combined with LPS

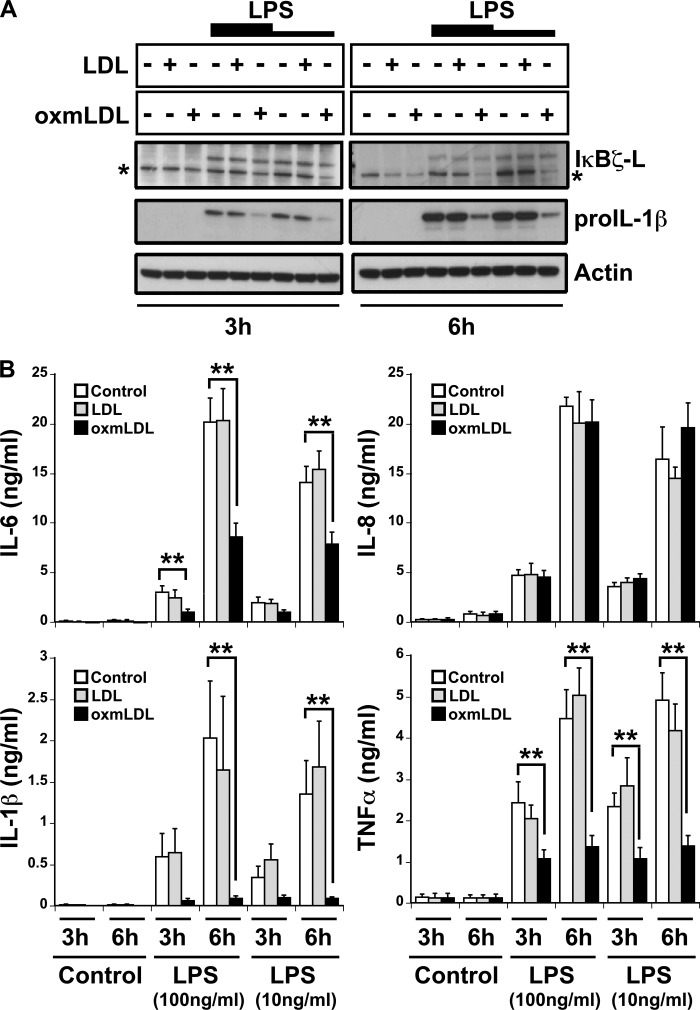

Because the monocytic expression of IκBζ, IL-6, and IL-8 protein occurred only with LDL and oxmLDL preparations that contained detectable endotoxin contamination, the monocytic response to the purer forms of LDL and oxmLDL was studied in the presence of LPS. As observed previously, IκBζ expression was undetectable in the samples treated with LDL or oxmLDL alone (Fig. 3A). Upon treatment with LPS, the expression of IκBζ and pro-IL-1β increased as has been reported (11), but did not change with the combination of LDL/oxmLDL with LPS. However, unlike the effect on IκBζ, pro-IL-1β expression dramatically decreased upon combining oxmLDL with LPS.

FIGURE 3.

Suppression of cytokine expression in oxmLDL-treated monocytes. Monocytes (2 × 106/ml) were treated with LDL and oxmLDL (25 μg/ml) in the presence and absence of LPS (100 and 10 ng/ml) for the indicated times. A, immunoblot for IκBζ, pro-IL-1β, and actin expression. B, protein expression for IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, and IL-1β analyzed by ELISA. The immunoblots are representative of four independent experiments, and bar values are represented as mean ± S.E. for four experiments. * represents nonspecific band. ** represents p < 0.05.

Additionally, the expression of IL-6, TNFα, and IL-1β followed the same pattern of expression as pro-IL-1β, with a 2–10-fold decrease in cytokine expression upon treatment with the combination of oxmLDL and LPS (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3B). However, IL-8 responded differently in that IL-8 expression was not suppressed by the combination stimulus of oxmLDL and LPS. Thus, oxmLDL selectively down-regulates specific proinflammatory responses when recognized in combination with the TLR4 ligand, LPS.

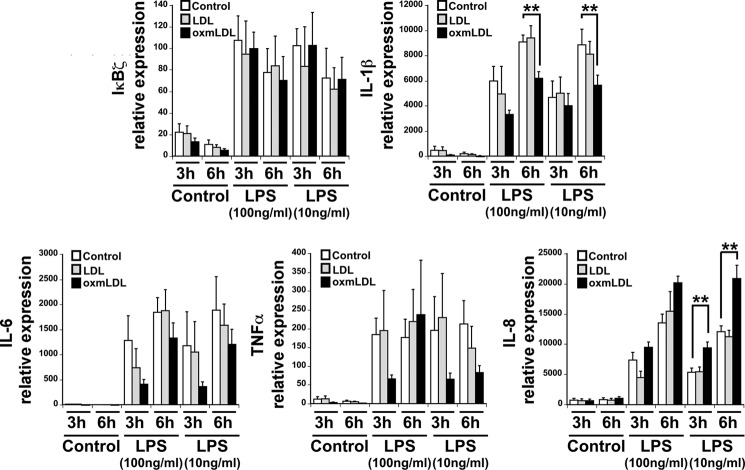

Gene Expression in Monocytes in Response to LDL and oxmLDL in the Presence of LPS

To characterize the cytokine suppression mediated by oxmLDL, we measured the cytokine mRNA levels in monocytes treated with preparations of LDL and oxmLDL in the presence and absence of added LPS. Akin to IκBζ protein expression, LDL did not further augment LPS-induced IκBζ gene expression. The gene expression of IL-1β increased upon treatment with LPS, which remained unchanged with the combination of LDL and LPS. However, the combination of oxmLDL and LPS decreased the expression of IL-1β, most significantly at 6 h (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Effect of oxmLDL on monocyte mRNA expression. Monocytes (2 × 106/ml) were treated with LDL and oxmLDL (25 μg/ml) in the presence and absence of LPS (100 and 10 ng/ml) for the indicated times. The cells were lysed, and total RNA was extracted, converted to cDNA, and analyzed for IκBζ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNFα gene expression by quantitative PCR. The bar values are represented as mean ± S.E. for four experiments. ** represents p < 0.05.

In contrast to the down-regulation of IL-6 and TNFα expression at the protein level, there was no significant change in their gene expression upon treatment with oxmLDL and LPS. The gene expression of IL-8 mimicked its protein pattern upon treatment with LPS alone, which remained unchanged by treatment with the combination of LDL and LPS. However, treatment with oxmLDL and LPS significantly increased the gene expression of IL-8. This is in contrast to the protein expression of IL-8, which remained unaffected in response to the combination of oxmLDL and LPS. This result suggests that oxmLDL in combination with LPS decreases the gene expression of the proinflammatory gene IL-1β but paradoxically enhances the gene expression of IL-8.

In an attempt to understand the possible mechanisms involved in oxmLDL-mediated suppression of proinflammatory gene expression, we also analyzed the gene expression of candidate anti-inflammatory genes: IL-1RII, IL-10, IL-1RN, and MRC-1, as well as PPARγ, the negative regulator of NFκB (supplemental Fig. S2). Although oxmLDL strongly suppressed the LPS effects on IL-10 and IL-1RN, it also enhanced the expression of IL-1RII and PPARγ. These changes in the gene expression patterns of different pro- and anti-inflammatory genes suggested that oxmLDL induces a unique monocyte phenotype in response to endotoxin challenge.

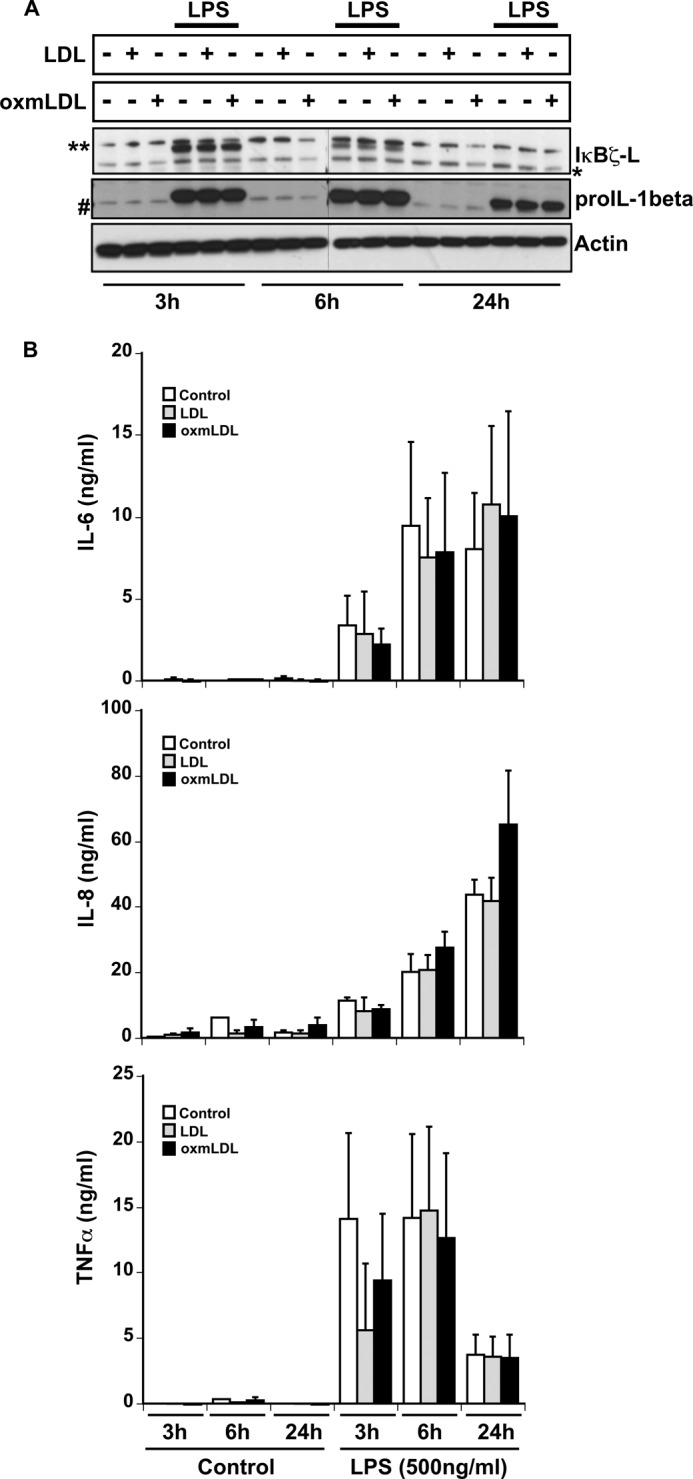

Macrophages Immune to Suppressive Effects of oxmLDL

As no significant response was observed in monocytes in response to low endotoxin preparations of oxmLDL, we turned to human macrophages, which utilize the scavenger receptor CD36 to take up oxmLDL in the process of becoming foam cells (18, 19). Human monocyte-derived macrophages were treated with low endotoxin preparations of LDL or oxmLDL alone or in combination with LPS for 3, 6, and 24 h. IκBζ and pro-IL-1β protein expression was induced by LPS but not by LDL or oxmLDL. Combining LDL or oxmLDL with LPS added no further response (Fig. 5A). The expression of IL-6, IL-8, and TNFα mimicked the protein expression of IκBζ and pro-IL-1β (Fig. 5B). The combination stimulus of LPS with either LDL or oxmLDL also showed no change in the expression of IL-6, IL-8, and TNFα. This was in contrast to the effect of oxmLDL on LPS-treated monocytes, where a decrease in expression of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFα was observed.

FIGURE 5.

Macrophage responses to oxmLDL treatment. Human macrophages (106/ml) were treated with LDL and oxmLDL (25 μg/ml) in the presence and absence of LPS (500 ng/ml) for the indicated times. A, cell lysates analyzed for IκBζ, pro-IL-1β, and actin expression by immunoblotting. B, cell supernatants analyzed for IL-6, IL-8, and TNFα expression by ELISA. The immunoblots are representative of three independent experiments, and the bar values are represented as mean ± S.E. for three independent experiments.

Because our experiments showed no significant response of human monocytes and macrophages to LDL and oxmLDL, the surface expression of the scavenger receptor CD36 was confirmed in the different cell populations (20, 21) (supplemental Fig. S3). Both populations of cells, human monocytes and macrophages, demonstrated similar relative mean fluorescence intensities for CD36. Additionally, both cell types expressed CD14, although the relative mean fluorescence intensities of CD14 expression were 2-fold higher in the monocytes than in the macrophages. This experiment suggests that the lack of a proinflammatory response to oxmLDL was not due to lack of CD36 expression.

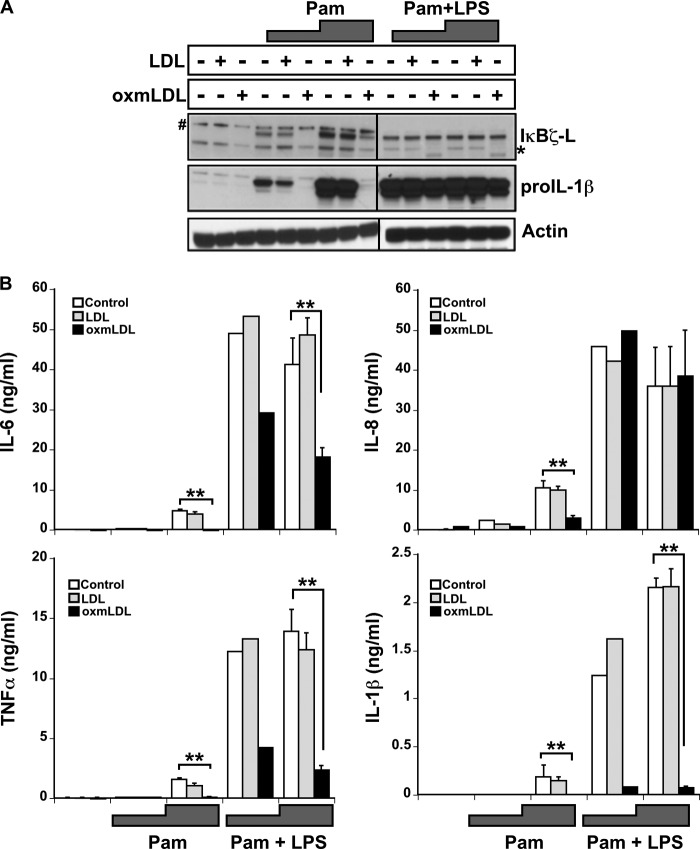

Monocyte Response to oxmLDL in the Presence of TLR2 Agonist

oxmLDL has been reported to activate proinflammatory responses in concert with TLR2 (22), and the scavenger receptor CD36 is a co-receptor for TLR2 (6, 7). Therefore, to evaluate the ability of oxmLDL to function in the presence of a TLR2-specific ligand, freshly isolated CD14+ human monocytes were incubated with oxmLDL and the TLR2 ligand PamCSK4 either alone or in combination with LPS for 6 h. The expression of IκBζ and pro-IL-1β was insignificant in response to LDL and oxmLDL (Fig. 6A). As expected, PamCSK4 (Pam) increased the expression of IκBζ and pro-IL-1β (10, 23). However, the TLR2-dependent PamCSK4 effect on IκBζ and pro-IL-1β was not augmented by the addition of LDL, mimicking the LDL- and TLR4-dependent LPS response (Fig. 3). Indeed, the expression of IκBζ as well as pro-IL-1β was suppressed in response to the combination stimulus of oxmLDL and PamCSK4.

FIGURE 6.

Monocyte response to oxmLDL in the presence of TLR2 agonist. Monocytes (2 × 106/ml) were treated for 6 h with LDL and oxmLDL (25 μg/ml) in the presence and absence of PamCSK4 (Pam) (5 and 50 ng/ml, respectively) or PamCSK4 with LPS (100 ng/ml). A, cell lysates immunoblotted for IκBζ, pro-IL-1β, and actin expression. B, protein expression for IL-6, IL-8, and TNFα as analyzed by ELISA. The immunoblots are representative of three independent experiments, and the bar values display the mean ± S.E. for three independent experiments (the bar values for the low dosage PamCSK4 treatment average two experiments). Vertical lines have been inserted to indicate repositioned gel lanes. * and # represent nonspecific bands. ** represents p < 0.05.

The expression of IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, and TNFα followed a similar pattern of expression as IκBζ and pro-IL-1β, with no change in the protein expression upon treatment with LDL or oxmLDL alone, but an increase upon treatment with PamCSK4 (Fig. 6B). This IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, and TNFα response was not affected by native LDL provided with PamCSK4, but was down-regulated 2–5-fold in response to treatment with oxmLDL and PamCSK4 (p < 0.05). The addition of LPS to the PamCSK4, although enhancing overall cytokine responses, showed a similar pattern of oxmLDL-induced cytokine suppression (p < 0.05) except for IL-8 (p = not significant) akin to the previous observation in human monocytes in response to oxmLDL and LPS. Thus, oxmLDL also suppresses human monocyte responses to both TLR2 and TLR4 ligands.

DISCUSSION

Atherosclerotic plaques represent focal areas of inflammation characterized by subintimal accumulations of monocytes that become “foamy” macrophages by taking up lipids (2, 24–27). oxmLDL, which is critically important in the pathogenesis of plaque formation, binds to the scavenger receptor, CD36, on monocytes and macrophages inducing foam cell formation that have been linked to the pathogenesis of plaque formation (20, 28–34). The binding of oxmLDL to CD36 occurs in concert with the TLRs, notably TLR2 and TLR4, which have been linked to the downstream signal transduction and activation of the proinflammatory response (6, 7, 21, 35–40). Additionally, bacterial infections due to Chlamydia pneumoniae and Porphyromonas gingivalis activate TLR2 and TLR4, thereby inducing proatherogenic immune responses (41–43). These studies strongly implicate the involvement of pathogen recognition pathways of innate immune sensors in the development of atherosclerotic plaques.

This study evaluates the role of LDL and oxmLDL in the development of proinflammatory response in human monocytes and macrophages. Although the expression of the proinflammatory mediators IκBζ, IL-6, and IL-8 in human monocytes was significant in response to the standard preparation of oxmLDL, limulus amebocyte lysate assays discovered a significant level of endotoxin contamination in these standard samples. Because plasma lipoproteins have been noted to serve as transport vehicles for TLR ligands such as endotoxin, to eliminate the contamination concern, preparations of LDL and oxmLDL were created under stringent conditions (9). Human monocytes treated with the low endotoxin preparations of LDL and oxmLDL showed no significant change in of expression of IκBζ, IL-6, and IL-8 as compared with untreated controls. Furthermore, we confirmed that this dramatic difference between the two preparations of LDL/oxmLDL toward the expression of proinflammatory mediators was not a consequence of differences in the electronegative and peroxide content of the two preparations. This suggested that endotoxin contamination accounted for the true nature of oxmLDL effects on the expression of proinflammatory mediators and cytokines (Fig. 1). Additionally, other intermediate forms of LDL (mmLDL, oxLDL, and oxmLDL), when prepared in a stringent manner, also failed to induce cytokine release. These results further suggest the possibility that many previous studies linking different forms of oxidized LDL to proinflammatory cytokines may have been confounded by indirect TLR activation rather than a direct response of these modified lipoproteins binding to its receptor.

However, it is conceivable that effects of oxidized LDL on inflammation may represent a cooperative effect between the oxidized lipoproteins and pathogen-associated molecular patterns. Therefore, having ruled out an effect of oxmLDL alone, we turned to study the monocytic response to the combination stimulus of oxmLDL with the TLR4 ligand, LPS. The effect of TLR4 stimulation by LPS in monocytes has been previously documented (11, 44). To our surprise, the combination of oxmLDL and LPS dramatically down-regulated the expression of pro-IL-1β and the release of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNFα. Measurement of lactate dehydrogenase release confirmed that this suppression in cytokine release was not associated with cell death (supplemental Fig. S4). Of note, prior studies in murine systems also reported an oxmLDL-mediated immune suppression (45, 46). Additionally, the protein expression of IκBζ and the release of IL-8 remained unaffected, further validating the lack of cell toxicity in response to the combination of oxmLDL and LPS. Because cytokine release was not affected in samples treated with LPS and Cu2+ alone (data not shown), we eliminated the possibility that this down-regulation was a byproduct of Cu2+ present in the oxmLDL.

Although the detailed mechanisms responsible for the suppressive effects of oxmLDL are not included in the present study, the results provide some important clues. Firstly, evaluation demonstrated that the suppressive effect of combination stimulus of oxmLDL and LPS on IL-1β release was a consequence of down-regulation of IL-1β gene expression. Also, it appears that IL-6 and TNFα are also likely regulated by a decrease in mRNA responses (although not reaching the statistical significance seen with IL-1β). Evidence exists that oxidized phospholipids and oxysterol content of oxidized LDL down-regulate LPS-induced NFκB-mediated responses, thus leading to the hypothesis that lipid oxidation products may promote the shift from an acute inflammatory response to a chronic state (47, 48). Thus, it is conceivable that suppression of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFα is a consequence of a similar mechanism.

Secondly, the suppression of mRNA levels is not global; IκBζ mRNA levels remain unchanged, whereas IL-8 mRNA expression increases in response to the combined LPS oxmLDL stimulation. Enhanced expression of IL-8 in response to oxmLDL has been reported in endothelial cells and macrophages (49–51). Nevertheless, this increased mRNA expression of IL-8 did not lead to a concomitant increase in the protein expression of IL-8. This discrepancy in the gene and protein expression levels for IL-8 suggests a disconnect in the post-transcriptional regulation of IL-8 mRNA upon treatment with the combination of LPS and oxmLDL. Thus, taken as a whole, the differences in mRNA and protein levels between IL-8 and other cytokines suggest that the suppressive effect of oxmLDL is not due to a global inhibition of endotoxin detection by monocytes.

The effect of oxmLDL on cytokine responses was less dramatic in mature macrophages. Macrophages, like monocytes, failed to respond to purified oxmLDL. In contrast to the inhibition seen with monocytes, combining oxmLDL with LPS did not suppress the expression of IκBζ, pro-IL-1β, IL-6, or TNFα in human macrophages. This observation was true despite similar surface expression of CD36 as well as TLR4 in the two cell populations (52). This suggests that the lack of inhibition in human macrophages may be a consequence of regulatory changes in gene expression associated with differentiation from monocyte to macrophage In this regard, in agreement with our findings, a recent study has demonstrated the lack of significant changes in the LPS-induced proinflammatory responses mediated by oxmLDL-treated proinflammatory M1 macrophages (53). The same study also reports anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages as the predominant cells that take up oxidized LDL and progress to inflammatory M1 macrophages upon subsequent exposure to LPS, consequently expressing proinflammatory cytokines.

Although the occurrence of a similar switching event mediated by the combination of oxmLDL and LPS in our system is subject to future study, the phenotype of human monocytes treated with oxmLDL and LPS in our study suggests their commitment to a unique macrophage lineage. Signaling mediated by oxidized LDL in monocytes has been shown to activate the expression of PPARγ, a negative regulator of proinflammatory signaling that has been shown to direct human monocytes into alternative M2 macrophages (54, 55). Although we confirm an increase in PPARγ expression system (supplemental Fig. S2), the evaluation of other M2-specific genes revealed inconsistent changes. IL-1RII followed the PPARγ pattern, but IL-10 and IL-1RN were actually suppressed, and MRC-1 demonstrated no significant change in response to oxmLDL. Taken as a whole, this expression pattern suggests that despite the lack of a concerted commitment to a classic M2 macrophage phenotype, human monocytes upon treatment with oxmLDL generally exhibit a unique anti-inflammatory phenotype.

Because the oxmLDL receptor, CD36, is better characterized as a modulator of TLR2 function as compared with TLR4, the TLR2 ligand PamCSK4 was also tested for potential synergy with oxmLDL (6, 8). Although PamCSK4 in combination with oxmLDL consistently suppressed the expression of proinflammatory mediators as well as IκBζ and IL-8, oxmLDL suppressed the induction of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFα but not IκBζ and IL-8 when PamCSK4 was combined with LPS (Fig. 6). The rescue of the expression of IκBζ and IL-8 by the addition of LPS to oxmLDL and PamCSK4 suggests that signaling mediated by TLR4 overcomes the suppressive effect of oxmLDL on PamCSK4-induced expression of IκBζ and IL-8. These findings imply that the suppressive effect of oxmLDL may be more specific to TLR2 signaling events, consistent with the proven cooperativity between CD36 and TLR2 (6, 8).

In conclusion, our studies demonstrate that LDL and oxmLDL are unable to elicit an active proinflammatory response from human monocytes and macrophages when prepared in a low endotoxin environment. Moreover, we demonstrate that oxmLDL suppresses the LPS-induced expression and release of specific proinflammatory mediators and cytokines. Furthermore, the suppressive effect of oxmLDL for the expression and release of proinflammatory cytokines and mediators was more specific to TLR2 signaling as compared with TLR4 signaling. Thus, our findings not only contradict the popular concept of proinflammatory signaling mediated by oxmLDL but also suggest that oxmLDL cooperates negatively with TLR ligands for specific human monocyte proinflammatory responses.

Acknowledgments

We thank Freweine Berhe, Jennifer Hollyfield, and Amy Gross for technical assistance through the course of this study. We also thank the Dorothy M. Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute (DHLRI) Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Analysis Core for assistance with the flow cytometry experiments.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 HL089440 (to M. D. W). This work was also supported by an American Heart Association Great Rivers Affiliate predoctoral fellowship (to Y. K.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

- oxmLDL

- oxidatively modified low density lipoprotein

- mmLDL

- minimally modified LDL

- oxLDL

- oxidized LDL

- Bis-Tris

- 2-(bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino)-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- IL-1R

- interleukin-1 receptor

- PPARγ

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ.

REFERENCES

- 1. Carter A. M. (2005) Inflammation, thrombosis, and acute coronary syndromes. Diab. Vasc. Dis. Res. 2, 113–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Libby P., Theroux P. (2005) Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. Circulation 111, 3481–3488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Parthasarathy S., Raghavamenon A., Garelnabi M. O., Santanam N. (2010) Oxidized low density lipoprotein. Methods Mol. Biol. 610, 403–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Greaves D. R., Gordon S. (2009) The macrophage scavenger receptor at 30 years of age: current knowledge and future challenges. J. Lipid Res. 50, (suppl.) S282–S286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Silverstein R. L., Febbraio M. (2009) CD36, a scavenger receptor involved in immunity, metabolism, angiogenesis, and behavior. Sci. Signal 2, re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hoebe K., Georgel P., Rutschmann S., Du X., Mudd S., Crozat K., Sovath S., Shamel L., Hartung T., Zähringer U., Beutler B. (2005) CD36 is a sensor of diacylglycerides. Nature 433, 523–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jimenez-Dalmaroni M. J., Xiao N., Corper A. L., Verdino P., Ainge G. D., Larsen D. S., Painter G. F., Rudd P. M., Dwek R. A., Hoebe K., Beutler B., Wilson I. A. (2009) Soluble CD36 ectodomain binds negatively charged diacylglycerol ligands and acts as a co-receptor for TLR2. PLoS. One 4, e7411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Triantafilou M., Gamper F. G., Haston R. M., Mouratis M. A., Morath S., Hartung T., Triantafilou K. (2006) Membrane sorting of Toll-like receptor (TLR)-2/6 and TLR2/1 heterodimers at the cell surface determines heterotypic associations with CD36 and intracellular targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 31002–31011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hansson G. K., Hermansson A. (2011) The immune system in atherosclerosis. Nat. Immunol. 12, 204–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamamoto M., Yamazaki S., Uematsu S., Sato S., Hemmi H., Hoshino K., Kaisho T., Kuwata H., Takeuchi O., Takeshige K., Saitoh T., Yamaoka S., Yamamoto N., Yamamoto S., Muta T., Takeda K., Akira S. (2004) Regulation of Toll/IL-1-receptor-mediated gene expression by the inducible nuclear protein IκBζ. Nature 430, 218–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Seshadri S., Kannan Y., Mitra S., Parker-Barnes J., Wewers M. D. (2009) MAIL regulates human monocyte IL-6 production. J. Immunol. 183, 5358–5368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Santanam N., Parthasarathy S. (1995) Paradoxical actions of antioxidants in the oxidation of low density lipoprotein by peroxidases. J. Clin. Invest. 95, 2594–2600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Raices R. M., Kannan Y., Bellamkonda-Athmaram V., Seshadri S., Wang H., Guttridge D. C., Wewers M. D. (2009) A novel role for IκBζ in the regulation of IFNγ production. PLoS. One 4, e6776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kannan Y., Yu J., Raices R. M., Seshadri S., Wei M., Caligiuri M. A., Wewers M. D. (2011) IκBζ augments IL-12- and IL-18-mediated IFNγ production in human NK cells. Blood 117, 2855–2863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Herzyk D. J., Allen J. N., Marsh C. B., Wewers M. D. (1992) Macrophage and monocyte IL-1β regulation differs at multiple sites: messenger RNA expression, translation, and post-translational processing. J. Immunol. 149, 3052–3058 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marsh C. B., Gadek J. E., Kindt G. C., Moore S. A., Wewers M. D. (1995) Monocyte Fcγ receptor cross-linking induces IL-8 production. J. Immunol. 155, 3161–3167 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marsh C. B., Lowe M. P., Rovin B. H., Parker J. M., Liao Z., Knoell D. L., Wewers M. D. (1998) Lymphocytes produce IL-1β in response to Fcγ receptor cross-linking: effects on parenchymal cell IL-8 release. J. Immunol. 160, 3942–3948 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huh H. Y., Pearce S. F., Yesner L. M., Schindler J. L., Silverstein R. L. (1996) Regulated expression of CD36 during monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation: potential role of CD36 in foam cell formation. Blood 87, 2020–2028 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Podrez E. A., Febbraio M., Sheibani N., Schmitt D., Silverstein R. L., Hajjar D. P., Cohen P. A., Frazier W. A., Hoff H. F., Hazen S. L. (2000) Macrophage scavenger receptor CD36 is the major receptor for LDL modified by monocyte-generated reactive nitrogen species. J. Clin. Invest. 105, 1095–1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rahaman S. O., Lennon D. J., Febbraio M., Podrez E. A., Hazen S. L., Silverstein R. L. (2006) A CD36-dependent signaling cascade is necessary for macrophage foam cell formation. Cell Metab. 4, 211–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Silverstein R. L. (2009) Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and arterial thrombosis: role of the scavenger receptor CD36. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 76, Suppl. 2, S27–S30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Björkbacka H. (2006) Multiple roles of Toll-like receptor signaling in atherosclerosis. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 17, 527–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beutler B. A. (2009) TLRs and innate immunity. Blood 113, 1399–1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aqel N. M., Ball R. Y., Waldmann H., Mitchinson M. J. (1984) Monocytic origin of foam cells in human atherosclerotic plaques. Atherosclerosis 53, 265–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schwartz C. J., Valente A. J., Sprague E. A., Kelley J. L., Suenram C. A., Rozek M. M. (1985) Atherosclerosis as an inflammatory process: the roles of the monocyte-macrophage. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 454, 115–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ross R. (1986) The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: an update. N. Engl. J. Med. 314, 488–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sato T., Takebayashi S., Kohchi K. (1987) Increased subendothelial infiltration of the coronary arteries with monocytes/macrophages in patients with unstable angina: histological data on 14 autopsied patients. Atherosclerosis 68, 191–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ylä-Herttuala S., Palinski W., Rosenfeld M. E., Parthasarathy S., Carew T. E., Butler S., Witztum J. L., Steinberg D. (1989) Evidence for the presence of oxidatively modified low density lipoprotein in atherosclerotic lesions of rabbit and man. J. Clin. Invest. 84, 1086–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Szmitko P. E., Wang C. H., Weisel R. D., de Almeida J. R., Anderson T. J., Verma S. (2003) New markers of inflammation and endothelial cell activation: Part I. Circulation 108, 1917–1923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Biwa T., Sakai M., Shichiri M., Horiuchi S. (2000) Granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plays an essential role in oxidized low density lipoprotein-induced macrophage proliferation. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 7, 14–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Collins R. F., Touret N., Kuwata H., Tandon N. N., Grinstein S., Trimble W. S. (2009) Uptake of oxidized low density lipoprotein by CD36 occurs by an actin-dependent pathway distinct from macropinocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 30288–30297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang W. Y., Li J., Yang D., Xu W., Zha R. P., Wang Y. P. (2010) OxLDL stimulates lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 expression in THP-1 monocytes via PI3K and p38 MAPK pathways. Cardiovasc. Res. 85, 845–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lopes-Virella M. F., Virella G. (2010) Clinical significance of the humoral immune response to modified LDL. Clin. Immunol. 134, 55–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Seshiah P. N., Kereiakes D. J., Vasudevan S. S., Lopes N., Su B. Y., Flavahan N. A., Goldschmidt-Clermont P. J. (2002) Activated monocytes induce smooth muscle cell death: role of macrophage colony-stimulating factor and cell contact. Circulation 105, 174–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krieger M. (1997) The other side of scavenger receptors: pattern recognition for host defense. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 8, 275–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Miller Y. I., Viriyakosol S., Binder C. J., Feramisco J. R., Kirkland T. N., Witztum J. L. (2003) Minimally modified LDL binds to CD14, induces macrophage spreading via TLR4/MD-2, and inhibits phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 1561–1568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miller Y. I., Viriyakosol S., Worrall D. S., Boullier A., Butler S., Witztum J. L. (2005) Toll-like receptor 4-dependent and -independent cytokine secretion induced by minimally oxidized low density lipoprotein in macrophages. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25, 1213–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schroder K., Tschopp J. (2010) The inflammasomes. Cell 140, 821–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Duewell P., Kono H., Rayner K. J., Sirois C. M., Vladimer G., Bauernfeind F. G., Abela G. S., Franchi L., Nuñez G., Schnurr M., Espevik T., Lien E., Fitzgerald K. A., Rock K. L., Moore K. J., Wright S. D., Hornung V., Latz E. (2010) NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature 464, 1357–1361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kawai T., Akira S. (2009) The roles of TLRs, RLRs, and NLRs in pathogen recognition. International immunology 21, 317–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Byrne G. I., Kalayoglu M. V. (1999) Chlamydia pneumoniae and atherosclerosis: links to the disease process. Am. Heart J. 138, S488–S490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yumoto H., Chou H. H., Takahashi Y., Davey M., Gibson F. C., 3rd, Genco C. A. (2005) Sensitization of human aortic endothelial cells to lipopolysaccharide via regulation of Toll-like receptor 4 by bacterial fimbria-dependent invasion. Infect. Immun. 73, 8050–8059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Triantafilou M., Gamper F. G., Lepper P. M., Mouratis M. A., Schumann C., Harokopakis E., Schifferle R. E., Hajishengallis G., Triantafilou K. (2007) Lipopolysaccharides from atherosclerosis-associated bacteria antagonize TLR4, induce formation of TLR2/1/CD36 complexes in lipid rafts, and trigger TLR2-induced inflammatory responses in human vascular endothelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 9, 2030–2039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Akira S., Uematsu S., Takeuchi O. (2006) Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124, 783–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hamilton T. A., Ma G. P., Chisolm G. M. (1990) Oxidized low density lipoprotein suppresses the expression of tumor necrosis factor-α mRNA in stimulated murine peritoneal macrophages. J. Immunol. 144, 2343–2350 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hamilton T. A., Major J. A., Chisolm G. M. (1995) The effects of oxidized low density lipoproteins on inducible mouse macrophage gene expression are gene- and stimulus-dependent. J. Clin. Invest. 95, 2020–2027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Leitinger N. (2005) Oxidized phospholipids as triggers of inflammation in atherosclerosis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 49, 1063–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ohlsson B. G., Englund M. C., Karlsson A. L., Knutsen E., Erixon C., Skribeck H., Liu Y., Bondjers G., Wiklund O. (1996) Oxidized low density lipoprotein inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced binding of nuclear factor-κB to DNA and the subsequent expression of tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1β in macrophages. J. Clin. Invest. 98, 78–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hirose K., Iwabuchi K., Shimada K., Kiyanagi T., Iwahara C., Nakayama H., Daida H. (2011) Different responses to oxidized low density lipoproteins in human polarized macrophages. Lipids Health Dis. 10, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mattaliano M. D., Huard C., Cao W., Hill A. A., Zhong W., Martinez R. V., Harnish D. C., Paulsen J. E., Shih H. H. (2009) LOX-1-dependent transcriptional regulation in response to oxidized LDL treatment of human aortic endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 296, C1329–1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hamilton T. A., Major J. A. (1996) Oxidized LDL potentiates LPS-induced transcription of the chemokine KC gene. J. Leukoc Biol. 59, 940–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Henning L. N., Azad A. K., Parsa K. V., Crowther J. E., Tridandapani S., Schlesinger L. S. (2008) Pulmonary surfactant protein A regulates TLR expression and activity in human macrophages. J. Immunol. 180, 7847–7858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. van Tits L. J., Stienstra R., van Lent P. L., Netea M. G., Joosten L. A., Stalenhoef A. F. (2011) Oxidized LDL enhances proinflammatory responses of alternatively activated M2 macrophages: a crucial role for Krüppel-like factor 2. Atherosclerosis 214, 345–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tontonoz P., Nagy L., Alvarez J. G., Thomazy V. A., Evans R. M. (1998) PPARγ promotes monocyte/macrophage differentiation and uptake of oxidized LDL. Cell 93, 241–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bouhlel M. A., Derudas B., Rigamonti E., Dièvart R., Brozek J., Haulon S., Zawadzki C., Jude B., Torpier G., Marx N., Staels B., Chinetti-Gbaguidi G. (2007) PPARγ activation primes human monocytes into alternative M2 macrophages with anti-inflammatory properties. Cell Metab. 6, 137–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]