Background: Aquaglyceroporins are transmembrane proteins that mediate flux of glycerol across cell membranes.

Results: The termini and the transmembrane core of yeast aquaglyceroporin Fps1 interplay to modulate the transport activity.

Conclusion: The pore properties of Fps1 are crucial for restricting channel activity.

Significance: This opens up new dimensions on how the glycerol transport is regulated by aquaglyceroporins.

Keywords: Aquaporin, Gating, Glycerol, Transport, Yeast, AQP, Aquaglyceroporin, Osmoregulation, Transmembrane Core

Abstract

Aquaglyceroporins are transmembrane proteins belonging to the family of aquaporins, which facilitate the passage of specific uncharged solutes across membranes of cells. The yeast aquaglyceroporin Fps1 is important for osmoadaptation by regulating intracellular glycerol levels during changes in external osmolarity. Upon high osmolarity conditions, yeast accumulates glycerol by increased production of the osmolyte and by restricting glycerol efflux through Fps1. The extended cytosolic termini of Fps1 contain short domains that are important for regulating glycerol flux through the channel. Here we show that the transmembrane core of the protein plays an equally important role. The evidence is based on results from an intragenic suppressor mutation screen and domain swapping between the regulated variant of Fps1 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the hyperactive Fps1 ortholog from Ashbya gossypii. This suggests a novel mechanism for regulation of glycerol flux in yeast, where the termini alone are not sufficient to restrict Fps1 transport. We propose that glycerol flux through the channel is regulated by interplay between the transmembrane helices and the termini. This mechanism enables yeast cells to fine-tune intracellular glycerol levels at a wide range of extracellular osmolarities.

Introduction

Water is essential for life, and the ability of a cell to actively maintain water homeostasis during osmotic stress is critical for shape, turgor, and transmembrane transport processes and to ensure proper conditions for biochemical processes. Aquaporins, which facilitate the selective movement of water (orthodox aquaporins) and other small molecules such as glycerol (aquaglyceroporins), have proven to play a key role in osmoadaptation in yeast and many other organisms (1–3). Although the water-transporting orthodox aquaporins have been extensively investigated, the aquaglyceroporins are still poorly characterized at both the molecular and the cellular level. Hence, it is essential to investigate the regulatory mechanisms of these channel proteins for a deeper understanding of their physiological roles in different organisms.

Osmotic stress is caused by changes in the concentration of dissolved molecules in the medium surrounding the cell. Under conditions of high osmolarity stress, bakers' yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae maintains osmotic equilibrium by producing and retaining high concentrations of glycerol as a compatible solute (4, 5). Glycerol is produced by the yeast itself, and the reaction is catalyzed by the glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase enzymes Gpd1 and Gpd2. Consequently, gpd1Δgpd2Δ mutants are unable to synthesize glycerol and are sensitive to high osmolarity conditions (6). The intracellular glycerol concentration in S. cerevisiae is to a large extent determined by the regulated activity of the aquaglyceroporin Fps1, here called ScFps1 (2, 5). Increased external osmolarity causes ScFps1 inactivation/closure to retain intracellular glycerol, whereas decreased external osmolarity causes channel reactivation/opening and fast release of excessive glycerol (2). Cells lacking ScFps1 are sensitive to hypo-osmotic shock due to the inability to quickly release turgor pressure to prevent bursting (2). The protein consists of a transmembrane core with six transmembrane helices (TM1–6)3 and two half-helices situated in loops B and E that fold back into the membrane, forming a seventh pseudo-transmembrane helix, and two termini facing the cytosol (7). The termini (N and C) have been shown to be involved in the regulatory properties of ScFps1, and specific parts of the termini are particularly important for the regulation of the protein transport activity. Those were named the N- and C-terminal regulatory domains (NRD and CRD) (supplemental Fig. S1) (2, 7–9). Deletion or specific point mutations in the regulatory domains result in channels with much higher glycerol transport activity than the wild type protein. Cells expressing these hyperactive versions of ScFps1 are unable to accumulate glycerol and consequently have difficulties in adapting to high osmolarity conditions (2, 7, 9). This can, however, be reversed by intragenic suppressor mutations found in parts of the ScFps1 protein facing the exterior (9). Although most studies on fungal aquaglyceroporins have traditionally been carried out in S. cerevisiae, ScFPS1-like genes are present in many sequenced yeast genomes (10). ScFps1 and its orthologs are here collectively referred to as Fps1 proteins.

Although the N- and C-terminal regulatory domains are highly conserved among the Fps1 orthologs (9), the length and the overall sequence of the termini show poor conservation (10). The variation in length of the hydrophilic extensions leads to proteins with rather different molecular weight. The longest Fps1 can be found in Zygosaccharomyces rouxii (692 residues), Fps1 in S. cerevisiae measures 669 amino acids, whereas the shortest ortholog is Ashbya gossypii Fps1 (476 residues) (10). A. gossypii is a filamentous fungus closely related to yeast and biotechnologically significant for production of riboflavin (11). Like S. cerevisiae, A. gossypii accumulates predominantly glycerol as a compatible solute in response to hyperosmotic conditions, and the glycerol seems to originate from biosynthesis rather than uptake (12).

In this study, we aim to reveal the specific characteristics of the Fps1 glycerol channel regulation. First, we show that the Fps1 ortholog in A. gossypii, AgFps1, is a hyperactive aquaglyceroporin when expressed in S. cerevisiae and hence an optimal Fps1 ortholog to study in comparison with ScFps1 to reveal the mechanisms governing Fps1 channel regulation. Second, we demonstrate that the hyperactivity of AgFps1, as well as the regulated activity of ScFps1, is not solely dependent on the termini. Third, we identify a suppressor mutation in the sixth transmembrane domain of a hyperactive mutant of ScFps1 that restricts channel activity, and we show that the corresponding amino acid in AgFps1 suppresses the hyperactivity of AgFps1. Taken together, the physiological data and the transport studies presented here clearly demonstrate the impact of the transmembrane core for Fps1 channel activity. Based on these data, we propose that the pore properties of the channel directly affect ScFps1 channel activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and Plasmids

The S. cerevisiae strain used in this study is W303-1A (MATa leu2-3/112 ura3-1 trp1-1 his3-11/15 ade2-1 can1-100 GAL SUC2 mal0) with additional deletions in fps1::HIS3 (2) and gpd1::TRP1 gpd2::URA3 (6)). All constructs were cloned in YEp181myc, a 2μ LEU2 plasmid with the c-myc epitope attached to the carboxyl terminus of the ScFPS1 and AgFPS1 alleles (2, 9). All sequences of primers used for cloning are listed in supplemental Table S1. The ORF of AgFPS1 was cloned behind the ScFPS1 promoter by fusion PCR, using primers 1–4. The fusion PCR product and YEp181myc vector were cleaved using restriction enzymes HindIII and BamHI, ligated, and subsequently transformed into E. coli Top 10 cells. For cloning of chimeras, the N and C termini were amplified with PCR using primers with ∼20 bases annealing to the 5′ and 3′ sequences of the termini and an additional ∼30 bases with homology to the flanking regions of the termini-coding sequences of the other FPS1 or in the YEp181myc vector. The exact fusion points for the chimeras are depicted in supplemental Fig. S1 and Fig. 3A. For AgFPS1-NSc, the N terminus of ScFPS1 was amplified using primers 5 and 6, and YEp181myc-AgFPS1 plasmid was cleaved with NcoI. For AgFps1-CSc, the C terminus of ScFPS1 was amplified using primers 7 and 8, and the YEp181myc-AgFPS1 plasmid was cleaved with SmaI. For ScFPS1-NAg, the N terminus of AgFPS1 was amplified using primers 9 and 10, and YEp181myc-ScFPS1 plasmid was cleaved with XhoI. For ScFPS1-CAg, the C terminus of AgFPS1 was amplified using primers 11 and 12, and the YEp181myc-ScFPS1 plasmid was cleaved with SmaI. The PCR products and cleaved vectors were combined by gap repair after co-transformation into yeast (13). Plasmids were rescued from yeast and transformed into E. coli for amplification.

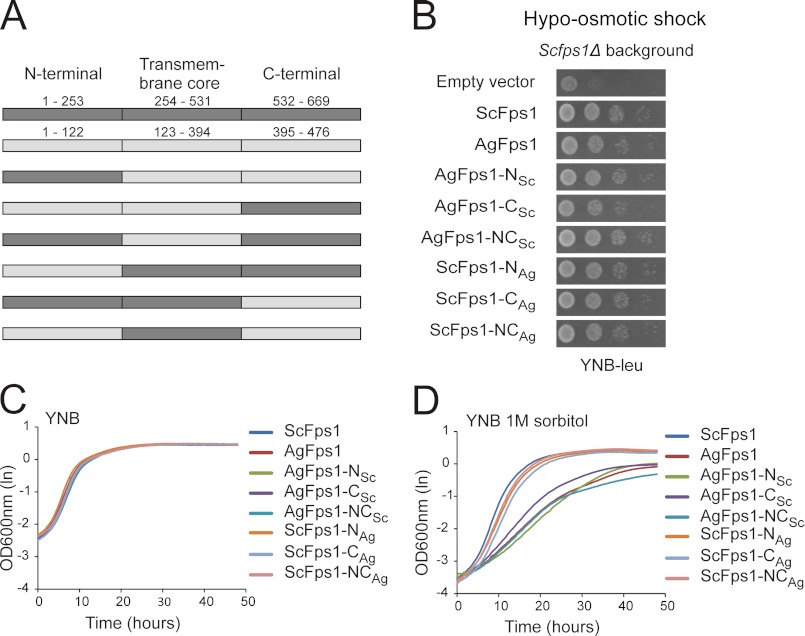

FIGURE 3.

Determination of the role of the transmembrane core in controlling Fps1 activity. A, sketch of ScFPS1 and AgFPS1 chimeras. Different combinations of the N and C termini and the transmembrane cores of ScFPS1 and AgFPS1 were fused together and expressed under the control of the ScFPS1 promoter in the YEp181myc plasmid. The numbers refer to the first and the last amino acids of each part of the chimera. For further details, see supplemental Fig. S1. B, growth phenotype of the Scfps1Δ mutant carrying empty plasmid or FPS1 alleles, pregrown on 1 m sorbitol and shifted to low osmolarity (no sorbitol). Increased survival rate when compared with cells with empty plasmid indicates functional channels. C and D, growth curves, monitored in a Bioscreen automatic reader, of Scfps1Δ cells expressing wild type and chimera proteins cultured in YNB medium (C) and in YNB medium containing 1 m sorbitol (D). Expression of hyperactive channels affects growth in high osmolarity medium. OD indicates optical density.

For intragenic suppressor mutation analysis, random mutations were introduced by transforming YEpmyc-ScFPS1 containing a point mutation N228A into the E. coli strain XL1-Red used for random mutagenesis from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA), following the manufacturer's recommendations. Transformants were grown in LB medium supplemented with 100 μg/μl ampicillin for 24 h, and thereafter, plasmids were isolated (Qiagen miniprep kit).

The G519S point mutation in ScFPS1 was created using site-directed mutagenesis approach (Stratagene) with primers 13 and 14, and G382S in AgFPS1 was created with primers 15 and 16. All constructs were sequenced to ensure correct ORFs and intact C-terminally fused myc tags.

Deletion of AgFPS1 was done by amplification of the GEN3 cassette (with primers 17 and 18) from plasmid pFAGEN3, kindly provided by Professor Jürgen Wendland at the Carlsberg Laboratory (14). The YEp181myc-AgFPS1 plasmid was linearized with NcoI and NheI, which cleave in the middle of AgFPS1 and remove ∼200 bp of the ORF. Insertion of the cassette into AgFPS1 was done using the yeast gap repair method. Successful insertion of the cassette was confirmed by PCR. The plasmid containing the cassette was rescued from yeast and transformed and propagated in E. coli. The deletion cassette with flanking homology to AgFPS1 was amplified by PCR, using primers 19 and 20, and transformed by electroporation into the A. gossypii leu2 strain (15), referred to as wild type, as described elsewhere (16). Correct integration of the deletion cassette into target locus and disruption of the AgFPS1 ORF in the homokaryotic Agfps1 null mutant were confirmed by PCR (14).

Growth Conditions and Growth Assays

Plate growth assays were performed as described previously (9). For liquid medium cultivation, cells pregrown in YNB-leu for 24 h were used to inoculate fresh YNB-leu medium with or without 1 m sorbitol as osmotic stress agent in Bioscreen plates. Bioscreen was set as described elsewhere (17) using a Labsystems Bioscreen C (Oy Growth Curves Ab Ltd., Helsinki, Finland). Sporulation of A. gossypii was done as described elsewhere (18). Purified A. gossypii spores were germinated and grown in YPD (2% yeast extract, 1% peptone, 2% glucose) with the addition of the antibiotic G418 at 200 μg/ml for mutant selection when required and in YNB (1.7 g/liter YNB without ammonium sulfate without amino acids, 0.77 g/liter CSM, 2 g/liter asparagine, and 1 g/liter myo-inositol) supplemented with 2% glucose or 2% glycerol.

Isolation of Intragenic Suppressor Mutations

Randomly mutated YEp181myc FPS1-N228A plasmids were transformed into an Scfps1Δ strain using the lithium one-step transformation protocol (19). Yeast cells were spread on selective medium (YNB-leu), and the transformants were restreaked on fresh medium before replica plating onto YNB-leu (positive control) and YNB-leu plus 0.8 m NaCl (selective). Cells were grown for 2–4 days, and positive clones were retested in growth assays for both hyperosmotic and hypo-osmotic shock. Plasmids were recovered from positive transformants, checked by restriction analysis, propagated in E. coli Top10 cells, and then retransformed into the Scfps1Δ strain for additional testing. Plasmids were also transformed into the gpd1Δgpd2Δ mutant and tested for growth on xylitol. All ScFPS1 alleles from transformants that scored positive in the tests were completely sequenced.

Glycerol Accumulation Measurements

For intracellular glycerol accumulation measurements, cells were pregrown in 50 ml of YNB-leu 2% glucose to mid-log phase (A600 of 0.5–0.7). At t = 0, NaCl was added to the medium to a final concentration of 0.8 m, and 1-ml aliquots were withdrawn at t = 5, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 min. Cells were harvested and resuspended in 1 ml of water and boiled at 100 °C for 10 min, and supernatants were stored in −20 °C. A600 was determined at all time points. IC [glycerol] was determined with a commercial kit (Roche Applied Science). Reaction was scaled down 12 times to a final reaction volume of 250 μl. Measurements were performed in a 96-well plate format using a Polar Star Omega plate reader (BMG Labtech). The mean value of [glycerol]/A600 ± S.D. (n = 3) was plotted against time.

Glycerol Transport Measurements

Yeast cells were grown in liquid YNB medium to an A600 of ∼1.2, harvested, washed, and resuspended in ice-cold MES buffer (10 mm MES, pH 6.0) to a density of 30 mg of cells/ml. Glycerol uptake was measured by adding glycerol to a final concentration of 100 mm “cold” glycerol plus 40 μm [14C]glycerol (142.7 mCi/mmol; Amersham Biosciences) as described previously (2, 9). The uptake assays were repeated at least three times, and the values are given with S.D.

Modeling of Fps1

To model the three-dimensional structure of the transmembrane core of ScFps1, we made use of the three-dimensional structure of the earlier published bacterial aquaglyceroporin, GlpF (20). The sequence of ScFps1 was threaded onto the structure of GlpF by using the “Fit raw sequence” command in SWISS-PDB viewer (21). The new structure, with the ScFps1 sequence, was inspected using PyMOL, and parts of the structure that looked sterically hindered were removed. The representative figure (see Fig. 5A) was made in PyMOL, representing the final model of ScFps1 (22).

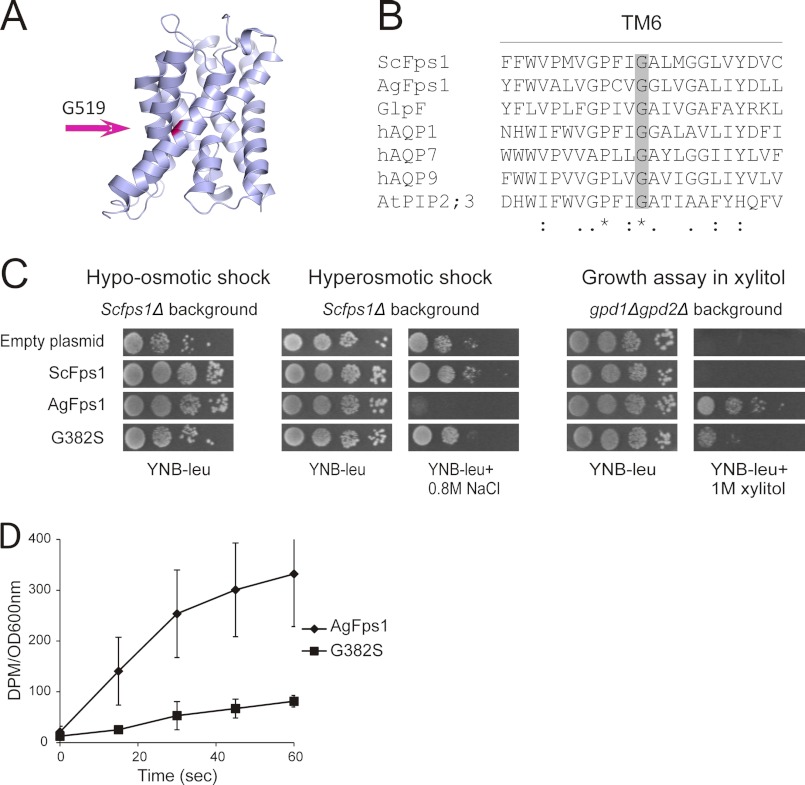

FIGURE 5.

Mutation of a conserved glycine in TM6 negatively affects glycerol transmembrane flux. A, structural model of the ScFps1 transmembrane core using the E. coli aquaglyceroporin GlpF structure as template. B, alignment of the TM6 from ScFps1, AgFps1, and other aquaporins or aquaglyceroporins from E. coli, human, and Arabidopsis thaliana. C, growth phenotypes of the Scfps1Δ transformed with empty plasmid or plasmids containing ScFPS1 alleles. Increased survival rate when compared with cells with empty plasmid indicates functional channels. Poor growth on NaCl in the Scfps1Δ mutant and growth on xylitol in the gpd1Δgpd2Δ mutant indicate hyperactive ScFps1 channels. D, influx of glycerol into Scfps1Δ mutant expressing AgFPS1 and AgFps1-G382S as a measure for AgFps1 channel activity. High influx indicates a hyperactive channel. Measurements were performed at least three times and error bars indicate S.D.

RESULTS

Fps1 from A. gossypii Mediates Glycerol Flux

ScFps1 has been reported previously to facilitate both uptake and export of glycerol in S. cerevisiae (5, 23). To investigate whether the ScFps1 ortholog AgFps1 is a functional glycerol channel in A. gossypii, the AgFPS1 ORF was deleted, and Agfps1Δ homokaryons were identified by PCR. To determine whether growth is affected by deletion of AgFPS1, YNB medium with either glucose or glycerol as carbon source was inoculated with wild type or Agfps1Δ spores, and postgermination growth was monitored after 18 h by bright field microscopy. Although growth of wild type and Agfps1Δ mycelium was identical in YNB supplemented by glucose, Agfps1Δ cultured in YNB glycerol medium displayed numerous nongerminated, needle-shaped spores and less filamentous growth when compared with wild type, suggesting slower growth of the deletion mutant (Fig. 1A). Further, glycerol influx in wild type and Agfps1Δ cells grown in YNB with glycerol was determined by measuring accumulation of [14C]glycerol over time. In accordance with growth phenotypes, the glycerol uptake assay confirmed that AgFps1 facilitates glycerol influx as Agfps1Δ showed a significantly slower glycerol accumulation when compared with wild type (Fig. 1B). ScFps1 also mediates transmembrane flux of arsenite in yeast (24). To address whether arsenite is a substrate for AgFps1, we monitored germination and subsequent growth of wild type and Agfps1Δ deletion mutant in the presence of arsenite. The observed growth phenotypes after 18 h clearly establish that the Agfps1Δ deletion mutant is less affected by arsenite than wild type (Fig. 1C), which is in agreement with the arsenite-resistant phenotypes observed for budding yeast lacking ScFPS1 (24).

FIGURE 1.

AgFps1 mediates glycerol flux in A. gossypii. A, growth of wild type and Agfps1Δ at 18 h after the addition of YNB supplemented with 2% glucose or 2% glycerol to spores. B, influx of glycerol in wild type and Agfps1Δ grown in YNB supplemented with 2% glycerol as a measure of AgFps1 channel activity. Measurements were performed at least three times, and error bars indicate S.D. C, growth of wild type and Agfps1Δ at 18 h after the addition of YPD with or without arsenite to spores. A and C, filamentous growth is indicated by white arrows, and nongerminated, needle-shaped spores are shown by black arrows. More needle-shaped spores indicate less efficient germination and growth.

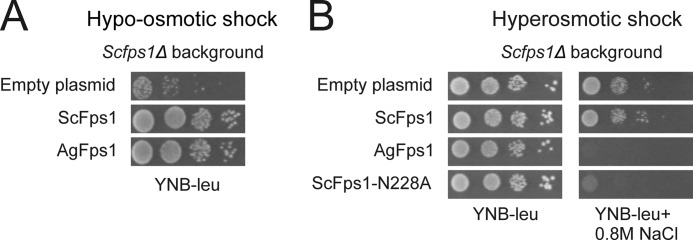

AgFps1 Is a Hyperactive Glycerol Channel

The sequence similarity between ScFps1 and AgFps1 and the fact that A. gossypii accumulates glycerol upon osmotic stress (4) suggest that AgFps1 could be involved in osmoregulation. To determine whether AgFps1 is a regulated channel like ScFps1, complementation analysis was performed by heterologous expression of AgFps1 in the S. cerevisiae fps1Δ strain. Growth assays upon hypo-osmotic stress showed that expression of AgFps1 confers a survival advantage, suggesting that AgFps1 acts as a functional glycerol transporter when expressed in S. cerevisiae (Fig. 2A). Next, the ability of yeast cells expressing AgFps1 to adapt to and grow in high osmolarity conditions was tested. Cells were exposed to 0.8 m NaCl, and the growth was monitored up to 3 days. As previously published, cells expressing ScFps1 survive the increase in external osmolarity as the activity of ScFps1 is diminished under these conditions, and thus, cells can accumulate glycerol (2, 9). However, cells expressing AgFps1 clearly render an osmosensitive phenotype, similar to that seen for cells expressing a hyperactive version of ScFps1, ScFps1-N228A, which contains a mutation in the N-terminal regulatory domain (Fig. 2B) (9). Hence, AgFps1 behaves as a hyperactive channel when expressed in S. cerevisiae.

FIGURE 2.

Characterization of AgFps1 by heterologous expression in S. cerevisiae. Growth phenotypes of the Scfps1Δ transformed with empty plasmid or plasmids containing FPS1 alleles were determined. A, Scfps1Δ mutants carrying empty plasmid, ScFPS1, or AgFPS1 were shifted from high (1 m sorbitol) to low (no sorbitol) osmolarity. A higher proportion of cells surviving the hypo-osmotic shock when compared with cells with empty plasmid indicates a functional Fps1 channel. B, growth phenotype of the Scfps1Δ mutant carrying empty plasmid, ScFPS1, AgFPS1, or ScFPS1-N228A in the absence (control) or presence of 0.8 m NaCl. Failure to grow on salt medium indicates expression of a hyperactive channel.

The Transmembrane Core Restricts the Activity of Fps1

Because AgFps1 is hyperactive upon expression in S. cerevisiae, the amino acid sequences of the N and C termini of ScFps1 and AgFps1 were compared. The regulatory domains were found to be highly conserved yet not identical, whereas the remaining portion of the termini showed poor conservation (supplemental Fig. S1). To determine whether the unrestricted glycerol flux in AgFps1 is due to termini properties, the N and C termini including the regulatory domains (NRD and CRD) were exchanged for the corresponding extensions in ScFps1, and vice versa, creating AgFps1-NSc, AgFps1-CSc, and AgFps1-NCSc and ScFps1-NAg, ScFps1-CAg, and ScFps1-NCAg (Fig. 3A, supplemental Fig. S1). All constructs proved to be functional as the expressed proteins could complement the growth defect of Scfps1Δ cells upon hypo-osmotic shock (Fig. 3B). Although growth was indistinguishable in YNB liquid medium (Fig. 3C), cells expressing the hyperactive channel AgFps1 as well as all the AgFps1 chimeras (with termini from ScFps1) showed an osmosensitive phenotype (i.e. reduced growth) in sorbitol-containing medium. On the other hand, cells expressing ScFps1 or the ScFps1 chimeras (with termini from AgFps1) showed no osmosensitivity (Fig. 3D). Thus, the hyperactivity of AgFps1 upon expression in S. cerevisiae is independent of the N- and C-terminal regulatory domains, and the transmembrane core must therefore play an essential role in restricting the transport activity of Fps1 channels.

A Transmembrane Core Glycine Residue Is Essential for ScFps1 Channel Activity

To obtain more specific information on how glycerol flux through Fps1 channels is regulated, we sought for intragenic suppressors of the N228A hyperactive variant of ScFps1. Cells containing ScFps1-N228A plasmids with potential suppressor mutations were screened for osmotolerance on plates containing 0.8 m NaCl. Of hundreds of transformants screened, 34 osmoresistant colonies were obtained. Because regain of osmotolerance can be either a consequence of an intragenic suppressor mutation that restores regulated glycerol flux through ScFps1-N228A or an abolished transport because a second mutation creates a nonfunctional channel, all hyperosmosis-resistant transformants were tested for survival after a hypo-osmotic shock. A gain-of-function mutation is a rarer event than a loss-of-function mutation, and hence, the majority of the osmotolerant transformants proved to be sensitive to hypo-osmotic shock, suggesting that they contain nonfunctional ScFps1 derivatives. Interestingly, however, we found one transformant, expressing ScFps1-N228A with the G519S suppressor mutation situated in TM6 that could both withstand a hypo-osmotic shock and survive hyperosmotic stress (Fig. 4A). The single mutant variant of the gene was generated; cells expressing ScFps1-G519S could also survive osmotic shocks in both directions, suggesting that ScFps1-G519S is a functional channel (Fig. 4A). In addition, we monitored growth of the gpd1Δgpd2Δ double mutant expressing the different ScFps1 variants. The gpd1Δgpd2Δ double mutant is unable to produce glycerol and hence cannot grow at elevated osmolarity caused by salt or by various polyols including xylitol. Expression of hyperactive aquaglyceroporins mediates uptake and intracellular accumulation of xylitol as compatible solute (substituting glycerol), thereby allowing growth (8). Although the gdp1Δgpd2Δ double mutant cells expressing ScFps1-N228A grew well on xylitol-containing plates, cells expressing ScFps1, ScFps1-N228A/G519S, or ScFps1-G519S did not grow on xylitol (Fig. 4A), indicating diminished transport under hyperosmotic stress conditions. To investigate whether growth phenotypes observed upon hyperosmotic conditions indeed are a result of the ability to accumulate glycerol, intracellular glycerol levels were measured over time after hyperosmotic shock. Cells expressing wild type ScFps1 rapidly accumulated glycerol under hyperosmotic conditions, whereas the N228A mutation caused poor accumulation due to a hyperactive channel activity. Interestingly, the N228A/G519S mutant, as well as the G519S single mutant, resulted in accumulation profiles comparable with wild type (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that growth of ScFps1-N228A/G519S during salt stress is indeed associated with glycerol accumulation. As a measure for channel transport activity, we next determined glycerol influx into Scfps1Δ cells expressing different ScFPS1 alleles by measuring the accumulation of [14C]glycerol in the cells over time. These data correlate well with the degree of sensitivity to 0.8 m NaCl (Fig. 4A) as the ScFps1-N228A shows a much higher transport capacity than wild type ScFps1 (Fig. 4C). The ScFps1-N228A/G519S double mutant, as well as ScFps1-G519S single mutant, transported much less glycerol than ScFps1-N228A during the first 60 s. In fact, both N228A/G519S and G519S transformants accumulated [14C]glycerol with profiles similar to ScFps1-expressing cells (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these data suggest that the ScFps1-N228A/G519S (and the G519S) mutant channels transport enough glycerol to mediate relief of excessive turgor pressure and survival upon hypo-osmotic conditions, yet allow glycerol to accumulate under high osmolarity conditions. Thus, a point mutation in the transmembrane core can overcome the hyperactivity caused by a mutation in NRD, emphasizing the importance of the transmembrane core in restricting channel activity.

FIGURE 4.

Identification of a transmembrane core residue important for channel activity. A, growth phenotypes of the Scfps1Δ transformed with empty plasmid or plasmids containing ScFPS1 alleles. Increased survival rate when compared with cells with empty plasmid indicates functional channels. Poor growth on NaCl in the Scfps1Δ mutant and growth on xylitol in the gpd1Δgpd2Δ mutant indicate hyperactive ScFps1 channels. B, cells were stressed with 0.8 m NaCl to allow accumulation of internally produced glycerol, and intracellular glycerol concentrations/A600 over time was determined. C, influx of glycerol into Scfps1Δ mutant expressing different ScFPS1 alleles as a measure of ScFps1 channel activity. High glycerol influx indicates a hyperactive channel. Measurements were performed at least three times, and error bars indicate S.D. OD indicates optical density.

The Conserved Glycine Also Plays a Critical Role in Glycerol Flux through AgFps1

To pinpoint the structural localization of the Gly-519 amino acid, a three-dimensional model of ScFps1 was generated by threading the sequence onto the GlpF structure, using Swiss PDB Viewer (20, 21). The Gly-519 amino acid is located in the middle of TM6 in ScFps1, in close proximity to TM4 (Fig. 5A). A BLAST analysis of ScFps1 revealed that Gly-519 is very well conserved, not only among Fps1 orthologs but also throughout the kingdom of aquaporins and aquaglyceroporins (Fig. 5B). To address whether a mutation in the corresponding glycine in AgFps1, Gly-382, has the same effect on transport capacity as the G519S mutation has on the hyperactive properties of the ScFps1-N228A channel, Gly-382 was mutated to a serine residue using site-directed mutagenesis. Indeed, although AgFps1 is hyperactive due to transmembrane core properties and not to a mutation in NRD as for ScFps1, the AgFps1-G382S expressing cells were able to withstand both high and low osmolarity stresses (Fig. 5C). Also, growth of gpd1Δgpd2Δ cells expressing AgFps1-G382S on xylitol plates was clearly affected when compared with growth of AgFps1-expressing cells (Fig. 5C). The minor growth detected under these conditions for AgFps1-G382S is, however, indicative for sparse transport of xylitol under high osmolarity conditions when compared with completely abolished transport of ScFps1 (Fig. 5C). In addition, glycerol influx measurements (Fig. 5D) were in good agreement with the growth phenotypes observed on NaCl and xylitol plates (Fig. 5C), demonstrating that the diffusion rate in AgFps1-G382S is lower when compared with AgFps1. Hence, these results suggest that the highly conserved glycine in TM6 in aquaporins and aquaglyceroporins plays a key role for the activity of Fps1 channels.

DISCUSSION

The rate of flux through eukaryotic aquaporins is frequently regulated at the post-translational level by gating or trafficking (25). The hallmark for aquaporins and aquaglyceroporins in yeast is the extended N and C termini. The termini have been suggested to act as a gate to restrict transport and have been reported to be important for survival of the microorganism during rapid environmental changes, such as osmotic pressure or temperature (2, 26). S. cerevisiae aquaglyceroporin Fps1 (here called ScFps1) plays a central role in yeast osmoadaptation by regulating the intracellular glycerol levels (2). Several studies have demonstrated that deletion or substitutions in regulatory domains of the N- and C-terminal extensions of ScFps1 result in channel hyperactivity and constitutive glycerol leakage upon high osmolarity conditions, conferring osmosensitivity to cells (2, 7–9, 27, 28). Here we demonstrate that although the termini are important for regulated glycerol flux, the transmembrane core of the protein plays an equally important role.

Domain swapping experiments between ScFps1 and AgFps1 showed that AgFps1, when expressed in S. cerevisiae, is hyperactive independently of the terminal regulatory domains, indicating that the high transport capacity of the protein is due to properties of the transmembrane core. The importance of the core properties was confirmed by substitution of a glycine in the middle of transmembrane domain six, which resulted in suppression of the hyperactivity of AgFps1, as well as of an ScFps1 variant mutated in NRD (N228A). Interestingly, when Kondo et al. (29) screened a human population for missense mutations in the aquaglyceroporin AQP7, a mutation that converts the corresponding glycine (Gly-264) to a valine was identified. The AQP7-G264V variant was impermeable to glycerol and water, and the individuals homozygous for the mutations demonstrated low levels of plasma glycerol during exercise (29). This glycine in TM6 is one of the few amino acids that are conserved among almost all aquaporins and aquaglyceroporins. In the three-dimensional structures of GlpF (Escherichia coli aquaglyceroporin) and PpAqy1 (Pichia pastoris yeast aquaporin), this particular glycine seems to play an important role for helix formation and to stabilize the whole structure by packing against TM4 and making several van der Waals contacts (20, 26, 30). Further, the TM4 plays a major role in the regulatory mechanisms in yeast aquaporin PpAqy1 by moving outwards and opening the channel upon phosphorylation as well as upon external pressure (26). The structure of PpAqy1 clearly shows that the channel is occluded by the N terminus (restricting water flux). However, molecular dynamic simulations suggest that the opening mechanism requires movements of the TMs as a subsequent event after external stimuli (26). The movement of the transmembrane helices in PpAqy1 upon external stimuli (phosphorylation or mechanical pressure) results in a widening of the pore. Hence, this scenario suggests that the pore size of the channel can influence the transport rate of substrates in aquaporins. Previously, it has been reported that the major selectivity mechanisms of aquaglyceroporins and orthodox aquaporins are steric restraints and hydrophobic effects (20, 31, 32) and that the transport rate is dependent on both the chemical structures and the size of the transported molecules (33). Thus, interplay between the pore size and the chemical structure of the substrate is likely to set the conditions for transport capacity in aquaporins. Similarly, aquaglyceroporins (such as ScFps1, bacterial GlpF, and mammalian AQP9) have been shown to transport polyols with a rate that is dependent on polyol size; the larger the molecule, the slower the diffusion rate (33, 34). Hence, a plausible mechanism for the restricted hyperactivity in Fps1 could be that when the glycine (Gly-519 in ScFps1-N228A or Gly-382 in AgFps1) is substituted to a serine (larger in volume and more polar), the positioning of TM4 would be affected and therefore make the pore tighter and the transport rate slower. Accordingly, the glycine substitution to a larger amino acid, as in AQP7-G264V, clearly affected the transport capacity of the channel (29). Along these lines, we note that uptake of xylitol is not as prominent in the AgFps1-G382S mutant as in AgFps1 (or ScFps1-N228A/G519S when compared with ScFps1-N228A). Differences in pore size could then also explain the more moderate transport rate of ScFps1 when compared with AgFps1.

In summary, we have shown by domain swapping experiments and intragenic suppressor mutation analysis that the ScFps1 transmembrane core properties are essential for restricting glycerol flux. Based on the results presented here and the previously acknowledged importance of the termini, we propose that the N- and/or C-terminal regulatory domains are important for restricting substrate transport rate by influencing the pore properties. Previous work shows that glycerol flux through Fps1 is inhibited by phosphorylation of the NRD (27, 28). Perhaps the NRD and/or CRD bind the transmembrane core and control glycerol flux by keeping the TMs in proper positioning. Changes in the phosphorylation status of the regulatory domains could then result in altered termini binding capacities, and consequently, a fine-tuning of the pore size. A tighter pore then prevents glycerol leakage under high osmolarity conditions, whereas a wider pore enables rapid glycerol export upon hypo-osmotic shock. Elucidating the regulatory mechanisms of ScFps1 is important for a better comprehension of yeast osmoregulation and for a greater understanding of the physiological roles of aquaglyceroporins in different organisms.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Professor Jürgen Wendland and Dr. Andrea Walther at the Carlsberg laboratory for the gift of the pFAGEN3 plasmid and for the help with laboratory issues concerning the deletion of AgFPS1. We thank Karin Rödström at Lund University for help with figures and Peter Dahl and Abraham Ericsson at the University of Gothenburg for help with initial experiments.

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, the Cancer Foundation, Vinnova, and the European Community (AQUAGLYCEROPORIN (Grant RTN35995), SLEEPING BEAUTY (Grant NEST 012674), and FP7 UNICELLSYS (Contract 201142)).

This article contains supplemental Table S1 and Fig. S1.

- TM

- transmembrane

- NRD

- N-terminal regulatory domain

- CRD

- C-terminal regulatory domain

- AQP

- aquaporin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Preston G. M., Agre P. (1991) Isolation of the cDNA for erythrocyte integral membrane protein of 28 kilodaltons: member of an ancient channel family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 11110–11114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tamás M. J., Luyten K., Sutherland F. C., Hernandez A., Albertyn J., Valadi H., Li H., Prior B. A., Kilian S. G., Ramos J., Gustafsson L., Thevelein J. M., Hohmann S. (1999) Fps1p controls the accumulation and release of the compatible solute glycerol in yeast osmoregulation. Mol. Microbiol. 31, 1087–1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. von Bülow J., Müller-Lucks A., Kai L., Bernhard F., Beitz E. (2012) Functional characterization of a novel aquaporin from Dictyostelium discoideum amoebae implies a unique gating mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 7487–7494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Förster C., Marienfeld S., Wilhelm R., Krämer R. (1998) Organelle purification and selective permeabilization of the plasma membrane: two different approaches to study vacuoles of the filamentous fungus Ashbya gossypii. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 167, 209–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Luyten K., Albertyn J., Skibbe W. F., Prior B. A., Ramos J., Thevelein J. M., Hohmann S. (1995) Fps1, a yeast member of the MIP family of channel proteins, is a facilitator for glycerol uptake and efflux and is inactive under osmotic stress. EMBO J. 14, 1360–1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ansell R., Granath K., Hohmann S., Thevelein J. M., Adler L. (1997) The two isoenzymes for yeast NAD+-dependent glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase encoded by GPD1 and GPD2 have distinct roles in osmoadaptation and redox regulation. EMBO J. 16, 2179–2187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hedfalk K., Bill R. M., Mullins J. G., Karlgren S., Filipsson C., Bergstrom J., Tamás M. J., Rydström J., Hohmann S. (2004) A regulatory domain in the C-terminal extension of the yeast glycerol channel Fps1p. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 14954–14960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Karlgren S., Filipsson C., Mullins J. G., Bill R. M., Tamás M. J., Hohmann S. (2004) Identification of residues controlling transport through the yeast aquaglyceroporin Fps1 using a genetic screen. Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 771–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tamás M. J., Karlgren S., Bill R. M., Hedfalk K., Allegri L., Ferreira M., Thevelein J. M., Rydström J., Mullins J. G., Hohmann S. (2003) A short regulatory domain restricts glycerol transport through yeast Fps1p. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 6337–6345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pettersson N., Filipsson C., Becit E., Brive L., Hohmann S. (2005) Aquaporins in yeasts and filamentous fungi. Biol. Cell 97, 487–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kato T., Park E. Y. (2012) Riboflavin production by Ashbya gossypii. Biotechnol. Lett. 34, 611–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Förster C., Marienfeld S., Wendisch V. F., Krämer R. (1998) Adaptation of the filamentous fungus Ashbya gossypii to hyperosmotic stress: Different osmoresponse to NaCl and mannitol stress. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 50, 219–226 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oldenburg K. R., Vo K. T., Michaelis S., Paddon C. (1997) Recombination-mediated PCR-directed plasmid construction in vivo in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 451–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Walther A., Wendland J. (2008) PCR-based gene targeting in Candida albicans. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1414–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wendland J., Dünkler A., Walther A. (2011) Characterization of α-factor pheromone and pheromone receptor genes of Ashbya gossypii. FEMS Yeast Res. 11, 418–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wendland J., Philippsen P. (2001) Cell polarity and hyphal morphogenesis are controlled by multiple Rho-protein modules in the filamentous ascomycete Ashbya gossypii. Genetics 157, 601–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Warringer J., Ericson E., Fernandez L., Nerman O., Blomberg A. (2003) High-resolution yeast phenomics resolves different physiological features in the saline response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 15724–15729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jorde S., Walther A., Wendland J. (2011) The Ashbya gossypii fimbrin SAC6 is required for fast polarized hyphal tip growth and endocytosis. Microbiol. Res. 166, 137–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gietz R. D., Woods R. A. (2002) Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol. 350, 87–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fu D., Libson A., Miercke L. J., Weitzman C., Nollert P., Krucinski J., Stroud R. M. (2000) Structure of a glycerol-conducting channel and the basis for its selectivity. Science 290, 481–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guex N., Peitsch M. C. (1997) SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18, 2714–2723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. DeLano W. L. (2010) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.3r1, Schrödinger, LLC, New York [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sutherland F. C., Lages F., Lucas C., Luyten K., Albertyn J., Hohmann S., Prior B. A., Kilian S. G. (1997) Characteristics of Fps1-dependent and -independent glycerol transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 179, 7790–7795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wysocki R., Chéry C. C., Wawrzycka D., Van Hulle M., Cornelis R., Thevelein J. M., Tamás M. J. (2001) The glycerol channel Fps1p mediates the uptake of arsenite and antimonite in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 40, 1391–1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Törnroth-Horsefield S., Hedfalk K., Fischer G., Lindkvist-Petersson K., Neutze R. (2010) Structural insights into eukaryotic aquaporin regulation. FEBS Lett. 584, 2580–2588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fischer G., Kosinska-Eriksson U., Aponte-Santamaría C., Palmgren M., Geijer C., Hedfalk K., Hohmann S., de Groot B. L., Neutze R., Lindkvist-Petersson K. (2009) Crystal structure of a yeast aquaporin at 1.15 Å reveals a novel gating mechanism. PLoS Biol. 7, e1000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mollapour M., Piper P. W. (2007) Hog1 mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation targets the yeast Fps1 aquaglyceroporin for endocytosis, thereby rendering cells resistant to acetic acid. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 6446–6456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thorsen M., Di Y., Tängemo C., Morillas M., Ahmadpour D., Van der Does C., Wagner A., Johansson E., Boman J., Posas F., Wysocki R., Tamás M. J. (2006) The MAPK Hog1p modulates Fps1p-dependent arsenite uptake and tolerance in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 4400–4410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kondo H., Shimomura I., Kishida K., Kuriyama H., Makino Y., Nishizawa H., Matsuda M., Maeda N., Nagaretani H., Kihara S., Kurachi Y., Nakamura T., Funahashi T., Matsuzawa Y. (2002) Human aquaporin adipose (AQPap) gene. Genomic structure, promoter analysis and functional mutation. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 1814–1826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bansal A., Sankararamakrishnan R. (2007) Homology modeling of major intrinsic proteins in rice, maize, and Arabidopsis: comparative analysis of transmembrane helix association and aromatic/arginine selectivity filters. BMC Struct. Biol. 7, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hub J. S., de Groot B. L. (2008) Mechanism of selectivity in aquaporins and aquaglyceroporins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 1198–1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Walz T., Hirai T., Murata K., Heymann J. B., Mitsuoka K., Fujiyoshi Y., Smith B. L., Agre P., Engel A. (1997) The three-dimensional structure of aquaporin-1. Nature 387, 624–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Heller K. B., Lin E. C., Wilson T. H. (1980) Substrate specificity and transport properties of the glycerol facilitator of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 144, 274–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Karlgren S., Pettersson N., Nordlander B., Mathai J. C., Brodsky J. L., Zeidel M. L., Bill R. M., Hohmann S. (2005) Conditional osmotic stress in yeast: a system to study transport through aquaglyceroporins and osmostress signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 7186–7193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]