Background: RNF8 and RNF168 are essential RING-E3 ubiquitin ligases that catalyze the formation of Lys-63 ubiquitin chains in the DNA damage response (DDR).

Results: We solved the crystal structures and probed the activity of RNF8 and RNF168 in vitro.

Conclusion: RNF168 likely acts downstream of RNF8 given its deficient activity.

Significance: Our data provide structural and catalytic insight into the relative activities of RNF8 and RNF168.

Keywords: DNA Damage Response, E3 Ubiquitin Ligase, Protein Complexes, Protein Structure, Ubiquitylation, Lys-63 Ubiquitylation, RING Domain, RNF168, RNF8

Abstract

The repair of DNA double strand breaks by homologous recombination relies on the unique topology of the chains formed by Lys-63 ubiquitylation of chromatin to recruit repair factors such as breast cancer 1 (BRCA1) to sites of DNA damage. The human RING finger (RNF) E3 ubiquitin ligases, RNF8 and RNF168, with the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating complex Ubc13/Mms2, perform the majority of Lys-63 ubiquitylation in homologous recombination. Here, we show that RNF8 dimerizes and binds to Ubc13/Mms2, thereby stimulating formation of Lys-63 ubiquitin chains, whereas the related RNF168 RING domain is a monomer and does not catalyze Lys-63 polyubiquitylation. The crystal structure of the RNF8/Ubc13/Mms2 ternary complex reveals the structural basis for the interaction between Ubc13 and the RNF8 RING and that an extended RNF8 coiled-coil is responsible for its dimerization. Mutations that disrupt the RNF8/Ubc13 binding surfaces, or that truncate the RNF8 coiled-coil, reduce RNF8-catalyzed ubiquitylation. These findings support the hypothesis that RNF8 is responsible for the initiation of Lys-63-linked ubiquitylation in the DNA damage response, which is subsequently amplified by RNF168.

Introduction

Among the various forms of DNA damage that must be identified and repaired by eukaryotic cells to maintain genomic stability, double strand breaks are particularly deleterious, as even a single double strand break can cause cell cycle arrest (1, 2). Homologous recombination (HR)3 is an essential pathway for the repair of these inevitable DNA lesions. HR relies on a diverse set of post-translational modifications to recruit downstream repair factors, including the breast cancer-associated protein BRCA1, to chromatin surrounding the double strand break to promote its repair.

HR is initiated by the recognition of the double strand break by factors such as the MRN complex, that lead to the activation of ataxia telangiectasia mutate (ATM) kinase, which phosphorylates multiple targets within proximity of the damage (3). Phosphorylation of the C-terminal tail of the histone variant H2AX by ATM facilitates the association of the scaffold protein mediator of DNA damage checkpoint 1 (MDC1) at these sites (4). MDC1 is then phosphorylated on multiple residues, which results in the binding of the E3 ubiquitin ligase, RNF8, via a selective interaction between the RNF8 forkhead-associated domain and one of three pThr-Gln-Xaa-Phe motifs in MDC1 (5, 6). RNF8 also contains a RING domain that functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase and interacts with the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme heterodimer, Ubc13/Mms2, to ubiquitylate histones near the lesion (6–8). It is thought that a second E3 ligase, RNF168, is then recruited to the growing ubiquitin chains via its motifs that interact with ubiquitin (MIUs), and, through an interaction between its RING domain and Ubc13/Mms2, amplifies the ubiquitin chains initiated by RNF8 (9, 10). Receptor-associated protein 80 (RAP80) then specifically binds to the ubiquitin chains through its tandem ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIMs), and through an interaction with the adapter protein Abraxas, BRCA1 is recruited (11–13). Finally, the ubiquitin signal is attenuated by the Ubc13 inhibitory factor, OTU domain ubiquitin binding 1 (OTUB1) (14).

Ubiquitylation catalyzed by Ubc13/Mms2 generates a unique form of polyubiquitin characterized by linkages between Lys-63 of one ubiquitin and the C-terminal carboxylate of the next ubiquitin in the chain, and unlike Lys-48-linked chains, Lys-63-linked polyubiquitylation does not target the substrate for proteolysis. Ubc13/Mms2 consists of a catalytic E2, Ubc13, which contains an active site cysteine that forms a thioester linkage with the C terminus of ubiquitin, thereby activating it for polyubiquitin chain formation. Mms2 is an E2-like protein that interacts with Ubc13 and facilitates the binding of the acceptor ubiquitin in an orientation to promote isopeptide bond formation between Lys-63 of the acceptor ubiquitin and the C-terminal thioester of the donor ubiquitin (15–19). The participation of Ubc13/Mms2 in distinct pathways is dependent on its interactions with different E3 partners. For example, interactions with the dimeric RING E3, TRAF6, recruits Ubc13 to the NF-κB signaling pathway, whereas interactions with the U-box E3, CHIP, enables Ubc13 to ubiquitylate chaperone-bound proteins (20, 21). Ubc13, as well as related E2s such as UbcH5, are selectively inhibited by OTUB1, a deubiquitylating enzyme, which binds the Ubc13∼Ub conjugate, likely directly inhibiting attack of the acceptor ubiquitin and blocking binding of RING E3 proteins (22, 23).

Although both RNF8 and RNF168 are important Ubc13 partners in the HR DNA repair pathway, the structural basis for their distinct functions is unclear. To address the roles of the RING domains of these E3 ligases, we probed their structures and abilities to catalyze Lys-63-linked polyubiquitylation. RNF8 adopts a dimeric structure, stabilized by an extended coiled-coil that is novel in the RING protein family, and interacts with Ubc13 through a surface that is conserved in the TRAF6 RING domain as well as the CHIP U-box. The interaction between RNF8 and Ubc13/Mms2 markedly catalyzes polyubiquitylation. RNF168, in contrast, is a monomeric RING domain, and, although the core RING domain adopts a structure similar to RNF8, it does not bind Ubc13 or catalyze polyubiquitylation to the same extent. Our data show that the RING domain of RNF168 alone is not sufficient for its activity and that it is likely dependent on its additional structural moieties. The ability of RNF8 to build de novo Lys-63 ubiquitin chains points to its role in the initiation of ubiquitylation in HR.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression, Purification, and Mutagenesis

OpenBiosystems cDNA of RNF8 (MHS4771-99611437) was used as a template to clone RNF8345–485 and RN8392–485 into the vector pGEX-6P-1 (GE Healthcare). RNF1681–113 used for structure solution was cloned from an OpenBiosystems cDNA template (MHS1010-7508235) into the pET28a-LIC (GenBank) vector using the In-Fusion CF Dry-Down PCR Cloning kit (Clontech). RNF1681–200 was cloned using the OpenBiosystems cDNA template (MHS1010-7508235) and ligated into pGEX-6P-1. RNF1681–113 used for biochemical assays was also inserted into the vector pGEX-6P-1.

Recombinant GST fusion RNF8 and RNF168 constructs and full-length Ubc13 and Mms2 were expressed in the vector pGEX-6P1 after transformation into Escherichia coli BL21 Gold (Invitrogen). Cells were pelleted, and resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 6.8, 400 mm NaCl, 10 μm ZnSO4 and 1 μl/ml β-mercaptoethanol) and 1× HALT Protease Inhibitor solution (Pierce). Cells were lysed using sonication and the lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 40,000 rcf for 30 min. GST-RNF8 and GST-RNF168 were separated from the cleared lysate via a glutathione-S-Sepharose column and washed with lysis buffer. Recombinant proteins were cleaved from the GST on column with Precision Protease and further purified by gel filtration chromatography. RNF8, Ubc13, and Mms2 were concentrated in gel filtration buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 6.8, 200 mm NaCl, 10 μm ZnSO4, and mm DTT) quantified by a BCA assay, and mixed in a 1:1:1 molar ratio, respectively. The complex was then purified by gel filtration, concentrated in gel filtration buffer, and quantified. Ubc13 and Mms2 were cloned as described previously (19), expressed, and purified in a manner identical to RNF8 and RNF168. Mutants of RNF8, Ubc13, and RNF168 were made using PCR mutagenesis and the recombinant pGEX-6P-1 plasmids as a template. Inserts containing point mutants were then religated into pGEX-6P-1 and sequenced.

RNF1681–113 used in structure solution was purified alternatively. After resuspension in 30 ml/liter bacterial culture of lysis buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 500 mm NaCl, 2 mm imidazole, pH 8.0, 1 mm PMSF, and 1× protease inhibitor (Sigma)), cells were lysed using sonication. A volume of 2.0 ml of settled Talon resin/40 ml of lysate (Clontech) was rocked with unclarified lysate for 60 min at 4 °C and transferred to a column. Protein was eluted with 30 ml of elution buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 500 mm NaCl, 5% glycerol, 250 mm imidazole, pH 8.0) and dialyzed overnight at 4 °C against 50 volumes of dialysis buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm DTT). The His6 tag was cut with thrombin, and the resultant protein was further purified by gel filtration and concentrated.

Crystallization and Structure Solution

The RNF8345–485/Ubc13/Mms2 complex was concentrated to 10 mg/ml in storage buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 6.8, 200 mm NaCl, 10 μm ZnSO4, and 1 mm DTT). Crystals were grown using vapor diffusion in 0.075 m sodium acetate, pH 4.5, and 1.0 m ammonium phosphate and grew to ∼200 μm after 1 month. Data were collected at beamline 12.3.1 at the Advanced Light Source. The complex structure was solved by Phaser using the Ubc13/Mms2 crystal structure (PDB ID code 1J7D) as a search model (24). Two molecules of Ubc13/Mms2 were found initially, and RNF8 was built manually into the positive Fo − Fc density. A homology model made up of multiple RING domains built manually in PyMOL and the zinc positions from an anomalous difference map were used as a guide for model building. The model was refined by rigid body refinement in PHENIX (25). The coiled-coil was built using an ideal model generated by the program CCCP (26). Statistics of data collection, processing, and refinement are provided in Table 1. Se-Met derivative data were collected to 9.0 Å. The RNF8345–485/Ubc13/Mms2 complex structure was used as a search model in Phaser against the Se-Met data, and the resulting pdb file was used to calculate an anomalous difference map and determine the methionine positions.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

Values in parentheses are for highest resolution shell.

| Parameter | RNF8345–483/Ubc13/Mms2 | RNF8345–485/Ubc13/Mms2 Se-Met | RNF1681–113 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal parameters | |||

| Space group | P42212 | P42212 | P43212 |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c (Å) | 205.3, 205.3, 235.4 | 204.0, 234.0, 234.2 | 49.7, 49.7, 110.2 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Data collection | |||

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.11585 | 0.97920 | 1.54 |

| Resolution (Å) | 123–4.80 | 200–9.00 | 45.3–2.12 |

| Rsyma | 6.3 (51.3) | 13.5 (35.8) | 12.4 (64.3) |

| I/σI | 24.3 (2.68) | 7.2 (2.66) | 40.1 (5.17) |

| Completeness (%) | 97.8 (99.4) | 73.1 (70.3) | 99.4 (99.7) |

| Redundancy | 6.8 (5.6) | 4.3 (4.4) | 53.4 (54.3) |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 123–4.80 | NAb | 45.3–2.12 |

| No. reflections | 45,858 | NA | 8,384 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 30.1/31.7 | NA | 18.9/21.5 |

| No. atoms | |||

| Protein | 10,547 | NA | 831 |

| Water | 0 | NA | 34 |

| Zinc | 10 | NA | 2 |

| Overall B-factor (Å2) | 175 | NA | 23.5 |

| Root mean square deviations | |||

| Bond lengths | 0.009 | NA | 0.024 |

| Bond angles | 1.44 | NA | 2.42 |

| Ramachandran | |||

| Preferred (%) | 93.2 | NA | 96.0 |

| Allowed (%) | 6.8 | NA | 4.0 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0 | NA | 0 |

a Rsym = Σ|(Ihkl) − <I>|Σ(Ihkl), where Ihkl is the integrated intensity of a given reflection.

b NA, not applicable.

RNF1681–113 crystals were grown at 18 °C using the sitting drop method by mixing equal volumes of protein (10 mg/ml) and crystallization buffer (1.5 sodium malonate, pH 7.3). Suitable crystals were cryoprotected by immersion in 2.4 m sodium malonate, pH 7.3, supplemented with 10% trimethylamine oxide (v/v) prior to freezing in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected using a home source (Rigaku FRE SuperBright). All data sets were integrated and scaled using the XDS package (27). The structure was solved using both molecular replacement and the weak phases derived from a Sulfur-SAD. MOLREP was used for molecular replacement with the model (PDB ID code 3FL2) (28). Automated model building using ARP/wARP, combined with iterative model building using the graphics program COOT, was used to build the final model (29). Maximum-likelihood and TLS refinement in REFMAC5 were used to refine the model (30, 31). Statistics of data collection, processing, and refinement are provided in Table 1. The Protein Data Bank accession codes for the RNF8345–485/Ubc13/Mms2 complex and RNF1681–113 are 4EPO and 3L11, respectively.

Size Exclusion Chromatography

All analytical size exclusion chromatography was done using a Superdex 75 10/300 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) at 4 °C. Various concentrations of free protein and complex were loaded onto the column with a volume of 100 μl and run at 0.5 ml/min using an Akta Purifier (GE Healthcare). An Amersham Biosciences UV-900 was used to detect protein eluting off the column. Column was standardized by running mixed standards (dextrin, BSA, ovalbumin, chymotrypsinogen, and RNase A), each at a concentration of 1 mg/ml and brought to an injection volume of 250 μl.

Multiangle Laser Light Scattering (MALLS)

Three samples of quantified RNF8345–485 and Ubc13 were brought up to a concentration of 200 μm RNF8345–485 and increasing concentrations of Ubc13 (100, 200, and 400 μm) in gel filtration buffer. The injection volume of the mixed samples was 100 μl. Samples were injected over a Superose 6 column, in line with a Wyatt Systems REX to detect protein elution via refractive index, and a DAWN MALLS. Data were analyzed with ASTRA, and molecular mass predictions were normalized to a BSA standard.

Ubiquitylation Assays

100 nm human E1 and 200 nm Ubc13/Mms2 were incubated with 0.25 μm recombinant E3 (RNF8 or RNF168) and brought up to 50 μl in ubiquitylation buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 6.8, 200 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm MgSO4, 10 μm ZnSO4, 0.1 mm DTT, 2 mm ATP, 5 mm creatine phosphate, 0.6 unit/ml creatine kinase, and 0.6 unit/ml inorganic phosphatase) and incubated at 37 °C. Samples were quenched with SDS-PAGE loading buffer at 2, 15, 60, 300, and 1200 min and resolved on a 15% (v/v) polyacrylamide gel. The protein was transferred to a Immobilon-P PVDF membrane and probed with mouse anti-ubiquitin IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were washed and incubated with a 1:10,000 dilution of anti-mouse-linked horseradish peroxidase, and the chemiluminescence reaction was activated using the Super Signal West Hisprobe kit (Pierce). Membranes were imaged by exposure to Kodak Biomax film and scanned.

RESULTS

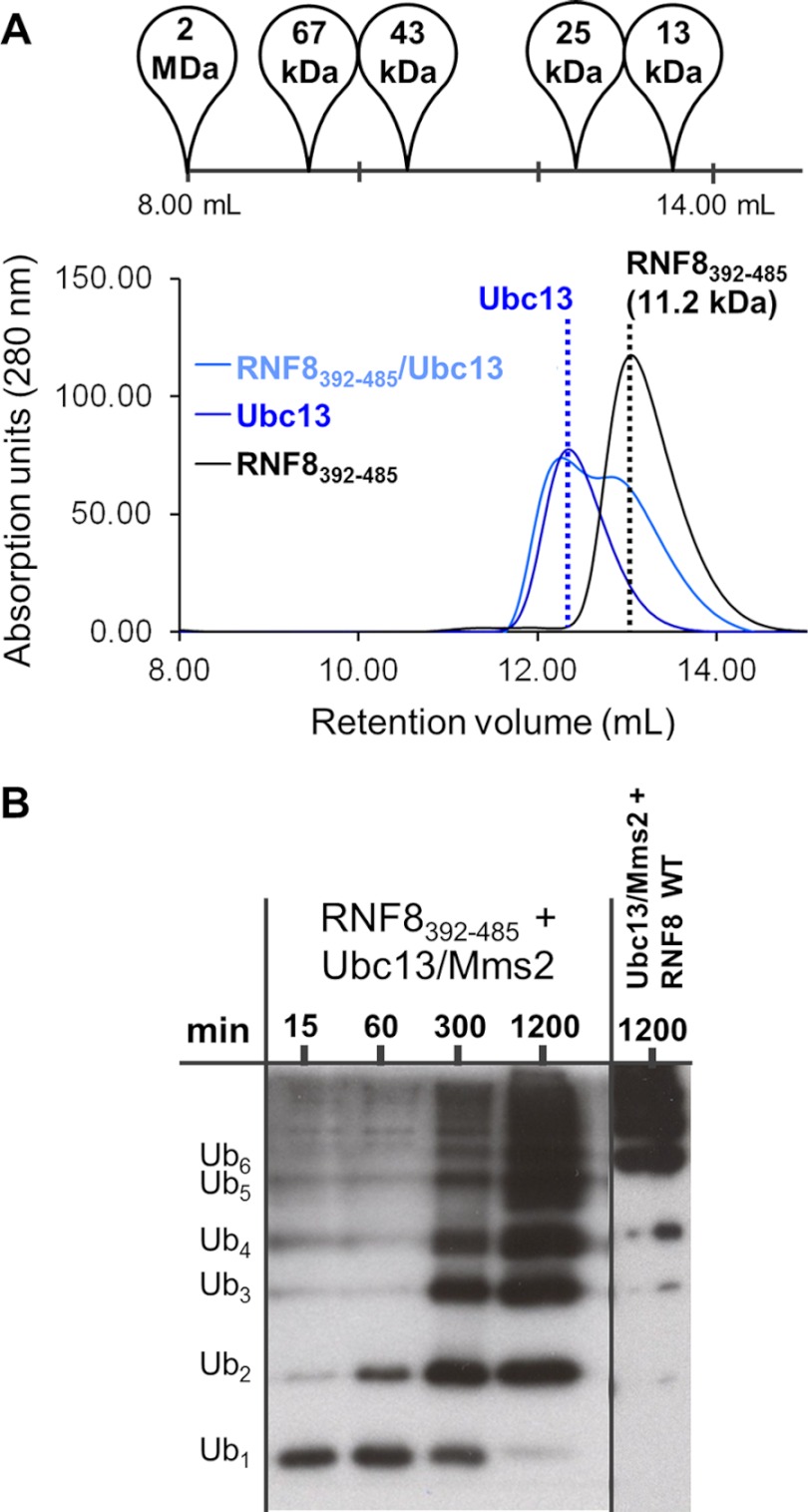

RNF8345–485 Interacts with and Activates Ubc13/Mms2 in Vitro

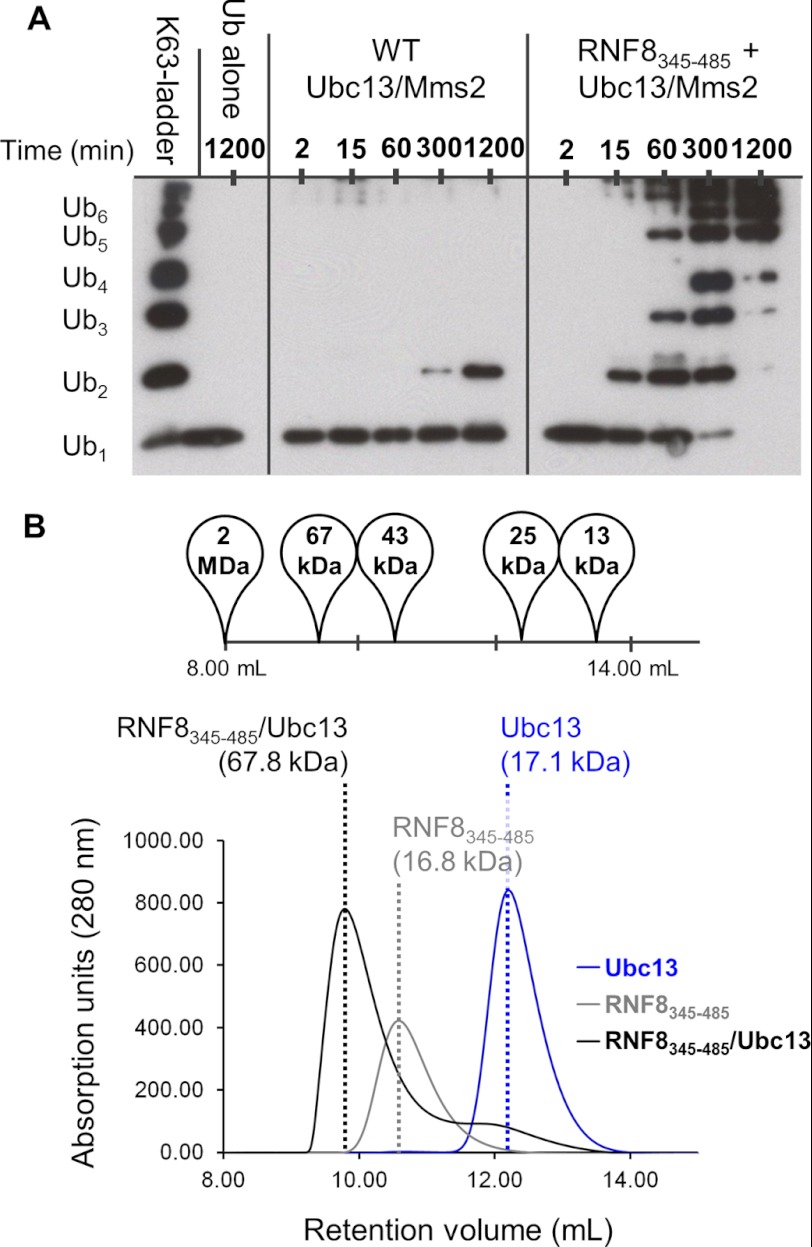

We set out to uncover a minimal, RING-containing domain of RNF8 for detailed structural and functional studies. Secondary structure predictions suggested that large N- and C-terminal helices flank the RING domain (supplemental Fig. S1A). This is consistent with previous reports of a possible coiled-coil N-terminal to the RING domain (32). A construct encompassing both of these predicted helices and the RING domain (RNF8345–485) was expressed, purified, and used in an in vitro ubiquitylation assay to test its ability to build Lys-63-linked ubiquitin chains in combination with the E2 heterodimer, Ubc13/Mms2. RNF8345–485 catalyzes the formation of ubiquitin chains efficiently in vitro, whereas Ubc13/Mms2 alone catalyzes the formation of only diubiquitin after 20 h at 37 °C (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

RNF8345–485 binds Ubc13/Mms2 to catalyze Lys-63-linked polyubiquitylation. A, RNF8345–485 enhances Ubc13/Mms2 polyubiquitylation. B, RNF8345–485 forms a complex with Ubc13 as determined by SEC. Peak elution volume is marked by a dotted line, and composition and molecular mass is labeled above. The elution volumes of size standards are shown above.

Next, we used size exclusion chromatography (SEC) to test for stable interactions between RNF8345–485 and Ubc13/Mms2. RNF8345–485/Ubc13 elutes with a lower retention volume compared with free RNF8345–485, indicating a direct interaction between Ubc13 and RNF8 (Fig. 1B). The ternary complex of RNF8345–485/Ubc13/Mms2 forms a complex with a slightly lower retention volume than the RNF8/Ubc13 complex (supplemental Fig. S1B). The presence of all three components in the complex was verified by mass spectrometry. As expected, RNF8345–485 shows no interaction with Mms2 alone, confirming that the ternary complex between RNF8345–485 and Ubc13/Mms2 occurs between RNF8 and Ubc13 (supplemental Fig. S1B). An electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) titrating increasing Ubc13/Mms2 heterodimer into a constant concentration of RNF8 confirmed complex formation of RNF8345–485 and Ubc13/Mms2 (supplemental Fig. S1C).

The Crystal Structure of the RNF8345–485/Ubc13/Mms2 Complex

We crystallized and determined the structure of the RNF8345–485/Ubc13/Mms2 complex to 4.8 Å resolution, with three complexes in the asymmetric unit. The Ubc13/Mms2 heterodimer was used as a search model, and maps phased with two copies of Ubc13/Mms2 revealed clear Fo − Fc difference electron density of a 2-fold symmetric RNF8345–485 dimer (supplemental Fig. S2A). Analysis of an anomalous difference map revealed peaks for the positions of the pairs of zinc atoms coordinated within each of the RING domains, and an anomalous difference map calculated from a crystal containing selenomethionine-substituted RNF8345–485 was used to establish the amino acid sequence register of RNF8 (supplemental Fig. S2B). Immediately evident is a coiled-coil-mediated dimer formed between the helices N-terminal to the RING domain of the two protomers of RNF8 (Fig. 2A, and supplemental Fig. S2A). This is consistent with the observations from SEC, which show that RNF8345–485 is retained in the column and elutes at a much smaller retention volume than that expected for a 16.8-kDa protein, likely because of dimer formation and a larger Rg due to an elongated structure (Fig. 1B). The N termini of the coiled-coil helices form crystal contacts with the Mms2 of a complex related by crystal symmetry. Two of the complexes observed in the crystallographic asymmetric unit contain one RNF8 dimer and one Ubc13/Mms2 heterodimer. In the third complex a single RNF8 protomer lies on a crystallographic 2-fold axis, forming a complex that consists of one RNF8 dimer and two Ubc13/Mms2 heterodimers. In the two complexes that contain only one bound Ubc13 per RNF8 dimer, the Ubc13 binding surface of the unbound RNF8 protomer is not occluded, and based on the relative zinc positions in the two RNF8 RING domains, the structure does not seem to be distorted. Nevertheless, no interaction with Ubc13 is visible in the electron density. Conversely, the third complex that sits on the 2-fold axis is necessarily symmetrical, with both protomers of the RNF8 dimer interacting with a Ubc13/Mms2 heterodimer (supplemental Fig. S2C). In this structure, the coiled-coil is not visible in the electron density. This is likely because the crystal packing is such that the tip of the coiled-coil cannot make contacts with symmetry mates, as is observed in the other two complexes, resulting in increased flexibility.

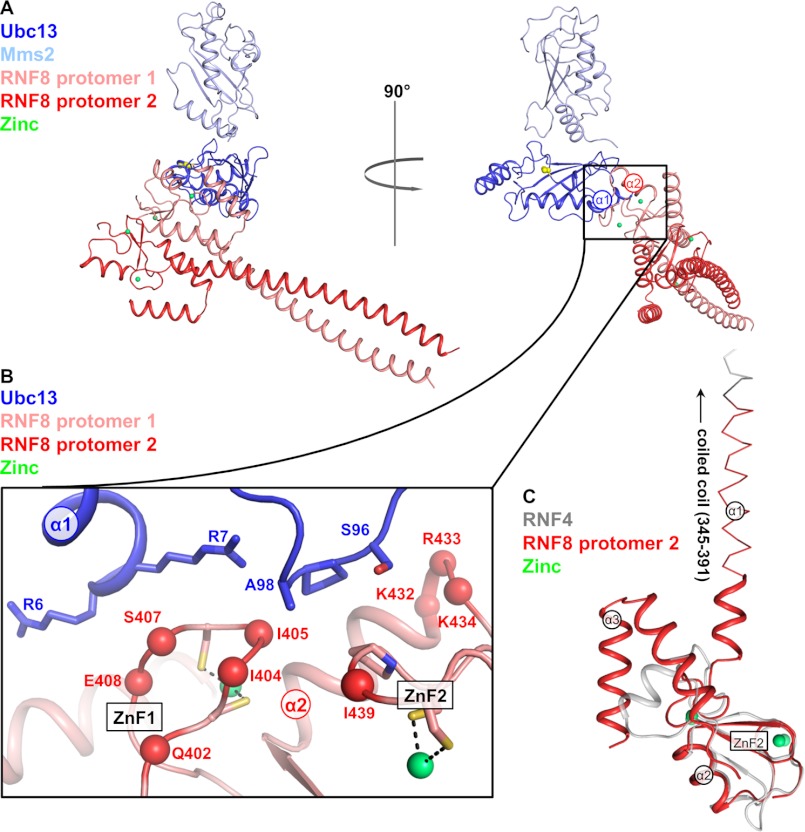

FIGURE 2.

Crystal structure of RNF8345–485/Ubc13/Mms2. A, two orientations of the crystal structure of the RNF8/Ubc12/Mms2 ternary complex. The RNF8 protomer interacting with Ubc13 is shown in salmon, and the unbound RNF8 protomer is shown in red. Ubc13 is shown in dark blue, and Mms2 is shown in light blue. The catalytic Cys-87 in Ubc13 is shown as yellow spheres, and the Zn atoms coordinated by the ZnFs of RNF8 are shown as green spheres. B, RNF8/Ubc13 binding interface. Important residues in complex formation are shown as spheres on RNF8 and sticks on Ubc13. RNF8 is shown in salmon, and Ubc13 is shown in dark blue. The Ser-Pro-Ala motif is highlighted with dots. C, alignment of a single RNF8 protomer with the crystal structure of RNF4 (PDB ID code 2XEU). RNF8 is shown in red, and RNF4 is shown in gray. The coiled-coil is shown as a line, and important structural features are labeled. The truncated construct of RNF8 lacks the coiled-coil as indicated by the transition between lines and scheme.

The structural similarity of RNF8 with other RING domains is shown with an alignment of the RING domain of RNF4 (Fig. 2C). The RING domain of RNF8 contains two prominent zinc fingers (ZnF1 and ZnF2) and an α-helix (α2) immediately following an internal two-stranded antiparallel β-sheet (β1 and β2). RNF8 contains an extended N-terminal helix (α1) preceding ZnF1 that forms the coiled-coil, as well as a C-terminal helix (α3), both of which form the RNF8 dimerization interface. N- and C-terminal helices are also found in other RING domain-containing protein dimers, including BRCA1-BARD1, TRAF6, and CHIP, although none of these contains an extended dimeric coiled-coil (20, 21, 33).

Although the crystal structure is low resolution, certain potential contacts can be identified between RNF8 and Ubc13. The ZnFs of the bound protomer of RNF8 interact with Ubc13, with Pro-438, Ile-439, Ile-404, and Ile-405 positioned to contact the Ser-Pro-Ala motif on Ubc13, similar to interactions observed between the RING domains of both TRAF6 and CHIP with Ubc13 (Fig. 2B). In the crystal structure of TRAF6 bound to Ubc13, Asp-57 just N-terminal to the first ZnF also makes electrostatic contacts with basic residues in α1 of Ubc13 (20). The conformation around Asp-57 in TRAF6 is not conserved in RNF8, but polar and acidic residues near ZnF1 (including Gln-402, Ser-407, and Glu-408) still come into proximity with the basic surface of Ubc13 α1.

The Stoichiometry of the RNF8/Ubc13 Complex Is 1:1 in Vitro

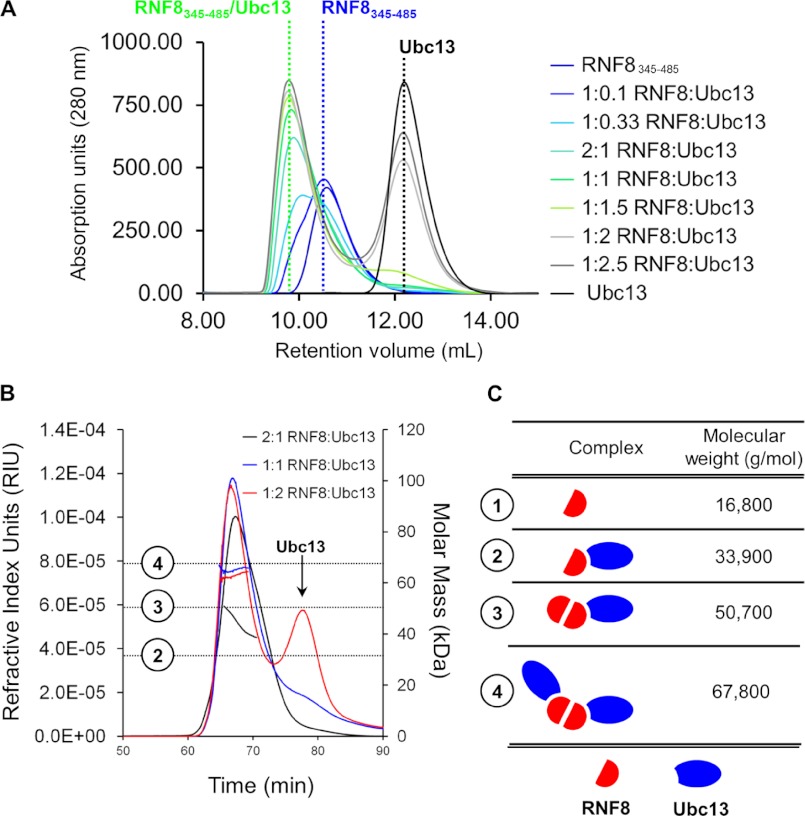

Interestingly, complexes with both 2:1 and 1:1 RNF8:Ubc13 ratios are observed in the crystal structure. Previously, RNF4 and RAD18 were shown to form an asymmetric complex with their corresponding E2 enzymes, with one RING domain dimer binding to one E2 (34, 35). To identify whether or not RNF8 forms an asymmetric complex, we performed a titration of Ubc13 into a constant concentration of RNF8345–485 on a gel filtration column (Fig. 3A). As the amount of Ubc13 is increased, the complex peak reaches its maximum height at a RNF8345–485:Ubc13 ratio of 1:1. Additional complex is not formed in the presence of excess Ubc13, suggesting a 1:1 stoichiometry. To verify this result, we ran MALLS on purified samples of the RNF8/Ubc13 complex at three different molar ratios (Fig. 3B). At a 2:1 molar ratio of RNF8345–485:Ubc13, the molecular mass prediction across the complex peak has a pronounced negative slope, indicating a heterogeneous species, likely consisting of both RNF8/Ubc13 complexes and free RNF8. At a molar ratio of 1:1 RNF8345–485:Ubc13, the molecular mass prediction is a constant 65.3 ± 2 kDa across the peak, corresponding to an RNF8 dimer bound to two Ubc13 monomers (complex 4 in Fig. 3C), and the molecular mass prediction does not change significantly under conditions of excess Ubc13 (Fig. 3B). Other possible complexes illustrated in Fig. 3C are not consistent with the predictions observed with MALLS. Taken together, these data suggest that each protomer of RNF8 within a dimer can independently bind a Ubc13/Mms2 heterodimer in solution.

FIGURE 3.

Stoichiometry of the RNF8/Ubc13 interaction. A, titration of increasing Ubc13 (20–500 μm) into a constant concentration of RNF8 (200 μm). Peak elution volumes are indicated by dotted lines, and the composition of each peak is labeled above. B, MALLS of purified samples of RNF8/Ubc13 complexes. The Gaussian curves indicate protein elution based on refractive index, and the horizontal curves indicated predicted molecular mass. C, scheme showing the possible complexes forming in solution. A dimer of RNF8 interacting with a two Ubc13 molecules fits the molecular mass predictions determined by MALLS.

RNF8 Interacts with Ubc13 through Its ZnF Motifs

Our structure reveals that the RNF8 RING finger interacts with Ubc13 in a manner that is similar to that of the RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF6 and the U-box-type E3 ubiquitin ligase, CHIP. This conserved binding interface involves four hydrophobic residues at the tips of the ZnFs in the RING domain (Ile-404, Ile-405, Pro-438, and Ile-439 in RNF8) that contact a conserved Ser-Pro-Ala motif in Ubc13 (Fig. 4A) (20, 21, 36). To demonstrate the function of this interaction in Ubc13-catalyzed ubiquitylation, we generated several point mutations at positions involved in the E2/E3 interaction and tested their activities in ubiquitylation assays. In Ubc13, we mutated the conserved serine and alanine to aspartic acid, generating S96D and A98D. In RNF8, three residues at the tips of the fingers, Ile-404, Ile-405, and Ile-439, were mutated to aspartic acid. I405D was not stable and did not over express, so an alternate mutant, I405A, was purified. This mutation was previously shown to retain RNF8 activity as well as the interaction between RNF8 and Ubc13 in vivo (37).

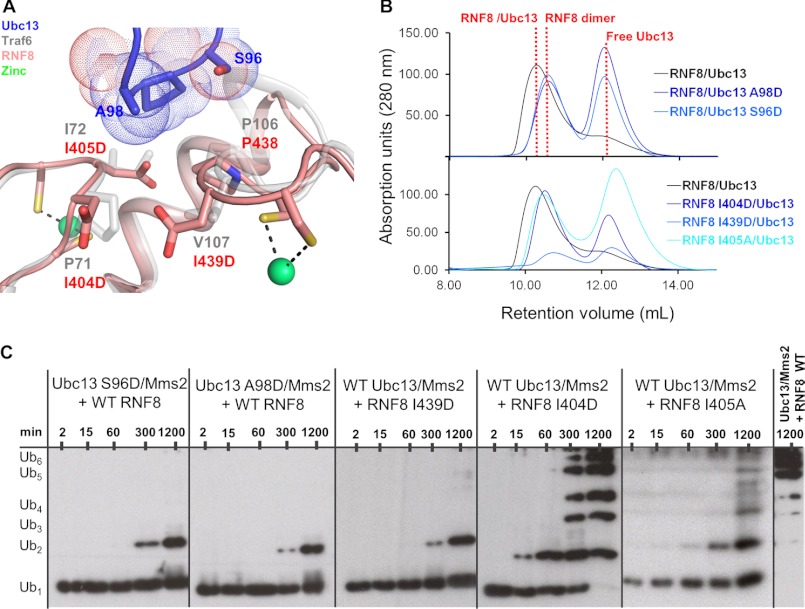

FIGURE 4.

RNF8 interacts with Ubc13 through its ZnFs. A, alignment of the RNF8 RING domain with the crystal structure of the TRAF6 RING domain bound to Ubc13 (PDB ID code 3HCU) showing important residues involved in E2/E3 complex formation. RNF8 is shown in red, TRAF6 RING in gray, and Ubc13 in blue. Aspartic acid side chain rotomers were predicted based on the relative side chain positions in the high resolution TRAF6 RING structure. B, gel filtration of mutant Ubc13 (upper) and RNF8 (lower). Composition is shown above each peak, and peak elution volume is indicated by a dotted line. C, ubiquitylation assays of mutant Ubc13 and RNF8 carried out for the indicated times.

The Ubc13 mutants, S96D and A98D, abolished complex formation as shown by SEC, as did the RNF8 mutants I404D, I405A, and I439D (Fig. 4B). The Ubc13 mutants, as well as RNF8 I439D, do not show any substantial ubiquitylation activity over the levels observed in the absence of RNF8, indicating that these residues are essential for the E2/E3 interaction. Conversely, RNF8 I404D shows ubiquitylation activity only slightly weaker than WT, and RNF8 I405A shows weak ubiquitylation activity, intermediate between that observed for RNF8 I439D and RNF8 I404D. This suggests that, whereas the affinity of the I404D and I405A RNF8 mutants for Ubc13 is reduced, sufficient residual binding remains to catalyze ubiquitin chain formation (Fig. 4C). These results confirm that the ZnFs of RNF8 are likely involved in the interactions with the conserved Ser-Pro-Ala motif in Ubc13, but that not all of the residues are involved equally in the interaction. This is supported by the fact that the residue in the position +1 to Cys-1 in ZnF1 (Ile-404 in RNF8) is not as conserved as the other residues in the RING domain (38).

The Coiled-coil Is Required for Dimerization and Complex Formation

To investigate the function of the coiled-coil, we made RNF8392–485, which contains the RING domain and the C-terminal helix, but a truncated N-terminal helix (Fig. 2C). This construct, lacking the first 47 residues of the active RNF8 (11.2 kDa) has a greatly increased retention time in SEC, consistent with a monomer, and does not show any interaction with Ubc13 (Fig. 5A). However, this construct does have significant catalytic activity, albeit reduced significantly compared with RNF8345–485 (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

RNF8392–485 does not interact tightly with Ubc13 and is deficient in Lys-63-Ub chain formation. A, gel filtration of RNF8392–485 free and with Ubc13. Peak elution volume is indicated with a dotted line, and composition and molecular mass are shown above the peaks. Elution volumes of standards are shown above the graph. B, ubiquitylation time course indicating that RNF8392–485 catalyzes polyubiquitylation less efficiently than RNF345–485.

Based on solvent-exposed surface area calculations, the coiled-coil accounts for roughly one third of the total dimerization interface of RNF8345–485, which explains the reduction in stability of the RNF8 dimer upon its truncation. In addition, the N-terminal helix that forms the coiled-coil extends directly into ZnF1, which contains the residues Ile-404 and Ile-405, both of which are important for the interaction with Ubc13 (Fig. 2B). It is possible that deletion of the coiled-coil results in a collateral destabilization of ZnF1, reducing Ubc13 binding affinity and loss of ubiquitylation activity.

We also examined the possibility that the coiled-coil could harbor cryptic tandem ubiquitin-interacting motifs, similar to the tandem ubiquitin-interacting motifs of RAP80, which facilitate recruitment of RAP80 to Lys-63-ubiquitylated chromatin (8, 13, 39) (supplemental Fig. S3). We mutated Ala-384 on RNF8, which corresponds to a critical ubiquitin binding residue in RAP80; however, this mutation did not interfere with complex formation or ubiquitylation (39). In addition, unlike GST-RAP80, GST-RNF8 immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads did not pull down Lys-63 polyubiquitin ladders, indicating that the RNF8 coiled-coil is unlikely to function as a ubiquitin-binding module.

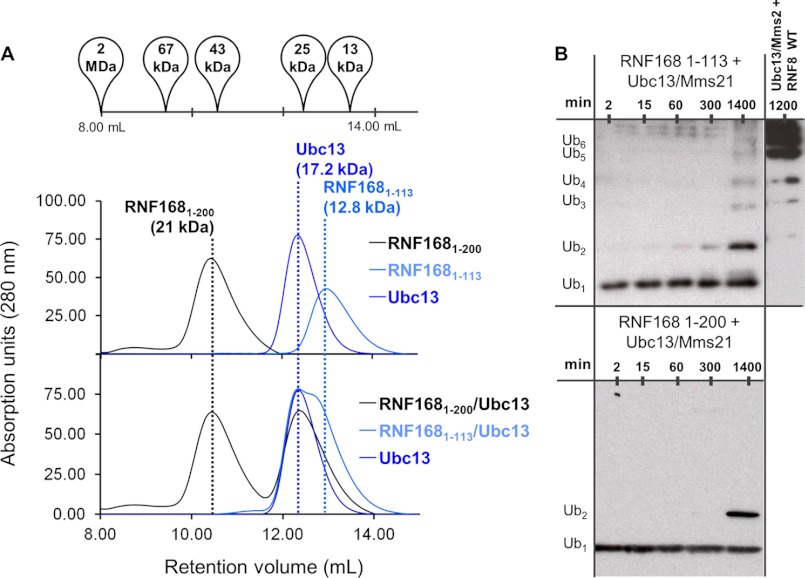

RNF168 Has Deficient Ubiquitylation Activity in Vitro

We next wanted to examine any possible differences in the structural and functional characteristics of RNF168 relative to RNF8. The two E3 ligases bear no significant sequence similarity outside of the core RING domains. Two RNF168 fragments were successfully purified. The construct 1–113 (12.8 kDa) contains only the RING domain and a small C-terminal extension, and 1–200 (23.1 kDa) contains the RING domain as well as one of two MIUs thought to be important for RNF168 function (10) (supplemental Fig. S1A). We were unable to purify full-length RNF168 containing the second MIU. Both constructs of RNF168 were deficient in forming Lys-63 ubiquitin chains in vitro; both RNF1681–113 and RNF1681–200 catalyze the formation of only very low levels of Lys-63 polyubiquitin ladders after 24 h at 37 °C (Fig. 6B). These data agree with previous reports that suggest that the second MIU in RNF168 is essential to its function (9). RNF1681–200 elutes at a volume consistent with a dimer on SEC, which is in agreement with a predicted coiled-coil in the region surrounding the first MIU domain. RNF1681–113, which lacks the predicted coiled-coil, runs as a monomer on SEC (Fig. 6A). In addition, neither RNF1681–113 nor RNF1681–200 shows any detectable binding to the Ubc13/Mms2 heterodimer in vitro by SEC, suggesting that the affinity for Ubc13 of these constructs is likely much weaker than that of RNF8345–485 (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Complex formation and ubiquitylation activity of RNF1681–113 and RNF1681–200. A, gel filtration of purified RNF168 constructs. Peak elution volume is indicated by a dotted line. Size and composition is labeled above each peak. Oligomerization is determined by elution volume relative to the standard elution volumes, shown above. B, ubiquitylation assays of RNF1681–113 and RNF1681–200.

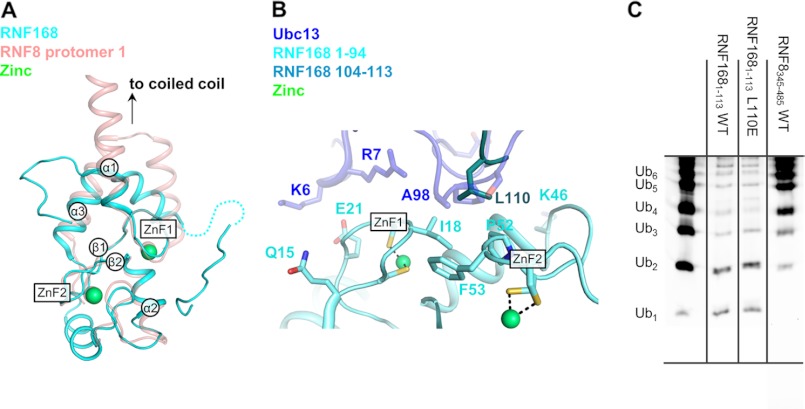

RNF168 Crystal Structure Shows Partial Occlusion of the Ubc13 Binding Site

The crystal structure of RNF1681–113 was solved to 2.12 Å resolution with a single molecule of RNF168 in the asymmetric unit. As expected, the RING domains of RNF8 and RNF168 show significant structural homology. The sequence identity between RNF8 and RNF168 is ∼40%, and their core RING domains align with a root mean square deviation of 1.13 Å (Fig. 7A). The ZnFs, helix α2, and β-sheets 1 and 2 align very closely with RNF8. The N-terminal and C-terminal helices found in RNF8 are also conserved in RNF168. However, the N-terminal helix is very short, only about 5 residues; and the C-terminal helix, although kinked as in RNF8, is also shorter (Fig. 7A). This truncation of the dimerization interface in RNF168 compared with RNF8 may explain why this RING domain does not form a dimer in solution. A coiled-coil is predicted in RNF168 C-terminal to the RING domain around resides 170–200 (10) and is likely the main interface required if dimerization of RNF168 in fact occurs.

FIGURE 7.

Crystal structure of RNF1681–113 shows partial occlusion of the Ubc13 binding site. A, crystal structure of RNF1681–113 (cyan) aligned with a single protomer of RNF8345–485 (red) in schematic representation. Important structural features are labeled. Zn atoms are shown as green spheres. B, potential binding interface of RNF168 and Ubc13 created by a structural alignment of RNF1681–113 with RNF8345–485. Conserved residues in the ZnFs of RNF168 are shown as sticks. The C-terminal tail of RNF1681–113 occluding the Ubc13 binding site is shown in dark green. RNF168 is shown in cyan, and Ubc13 is shown in semitransparent dark blue. C, ubiquitylation assay using RNF1681–113 L110E.

Although the RNF168 RING domain shows only very weak ubiquitylation activity in vitro, its catalysis of Ubc13/Mms2 mediated Lys-63-ubiquitin chains in HR has been shown previously (9, 10). ZnF1 in RNF168 retains the absolutely conserved hydrophobic residue (Ile-18) that is important for the RNF8/Ubc13 interaction, as well as Pro-52 in ZnF2 (Fig. 7B). The region near ZnF1 in RNF8 that interacts with Ubc13 is very similar in RNF168, with conserved residues Gln-15 and Glu-21 in a position to interact with α1 of Ubc13. In RNF168, it is possible that these residues may also contribute to binding. However, the presence of a glycine residue (Gly-17) in ZnF1 as opposed to a hydrophobic residue (Ile-404 in RNF8) may partially explain the reduced affinity of RNF168 for Ubc13.

Intriguingly, an alignment of the RNF168 structure onto one protomer of RNF8 positions Ubc13 into the likely binding site of RNF168, with the conserved Ser-Pro-Ala motif contacting the ZnF motifs in RNF168. However, residues C-terminal to the RNF168 RING domain (104–113) loop back around and Leu-110 partially occludes the Ubc13 binding site (Fig. 7B). To test whether this is biologically relevant, we mutated Leu-110 to a glutamic acid in an attempt to disrupt this interaction and thereby enhance Ubc13 binding. However, this mutant still fails to bind to Ubc13 as assayed by SEC (data not shown) and does not show increased ubiquitylation activity compared with WT (Fig. 7C). The relevance of the interaction of Leu-110 with the RNF168 RING ZnFs observed in the crystal structure is unclear.

DISCUSSION

RNF8 Likely Initiates Lys-63 Ubiquitylation in HR

The specific roles of RNF8 and RNF168 in the generation of Lys-63-linked polyubiquitin chains near the sites of DNA damage are still unclear. Here, we have probed the function of the structured regions of these proteins which encompass their RING domains. We show that in vitro, the dimeric RNF8 RING domain binds tightly to Ubc13 and catalyzes polyubiquitylation in a manner that is partially dependent upon its ability to form a dimer through its coiled-coil. Conversely, the monomeric RNF168 RING domain, RNF1681–113, does not interact tightly with Ubc13, resulting in deficient ubiquitylation activity compared with RNF8. The larger RNF1681–200, which contains a region predicted to form a coiled-coil and likely dimerizes, does not interact with Ubc13 and does not catalyze significant ubiquitylation activity.

Previous reports have suggested that although RNF8 initiates ubiquitylation at sites of DNA damage, RNF168 is required to amplify the signal (9, 10). The fact that the RNF8 RING has a much higher intrinsic affinity for Ubc13 than does the RNF168 RING is consistent with the proposed roles of RNF8 and RNF168 in the generation of Lys-63 polyubiquitin chains in the DNA damage response. We propose that the highly active RNF8 RING is able to build de novo chains, whereas RNF168 appears to be much more dependent on the presence of its MIU domains, which likely serve to target RNF168 to preinitiated chains. The affinity of full-length RNF168 for the polyubiquitin chains may make up for the inherently poor Ubc13 binding activity of its RING domain.

The differences in the Ubc13 binding and ubiquitylation activities of RNF8 and RNF168 may also explain why the Ubc13 inhibitor OTUB1 appears to act downstream of RNF168, without impeding RNF8 function at DNA damage foci (14). It is possible that the higher Ubc13 binding affinity of RNF8 may render it less susceptible to OTUB1 inhibition than RNF168. Also, the high intrinsic ubiquitin ligase activity of RNF8 could lead to depletion of the local monoubiquitin pool at nascent DNA damage foci. Because OTUB1 is allosterically regulated by free monoubiquitin (22, 23), this could further reduce OTUB1-mediated inhibition. However, after hand-off of ubiquitylation from RNF8 to RNF168, the weaker inherent Ubc13 binding activity of RNF168 could render this enzyme more susceptible to OTUB1 inhibition. The resultant reduction in ubiquitylation could lead to an increase in the monoubiquitin pool, initiating a feedback mechanism that would lead to shut down of ubiquitylation.

Isoleucines in ZnFs Are Not Equally Important for Ubc13 Interaction

Mutation of RNF8 Ile-405 to an aspartic acid results in an unstable protein that does not express, but mutating this same residue to an alanine results in a stable protein that does not form a tight complex with Ubc13, but is weakly active in a ubiquitylation assay. Because of the proximity of this residue to the hydrophobic face of α2 and Pro-438, it is likely that an aspartic acid cannot be accommodated at this position, and therefore disrupts RNF8 folding. Hydrophobic residues are strongly conserved at this position, which could explain how a substituted alanine may still make, albeit weaker, hydrophobic interactions with the Ser-Pro-Ala motif in Ubc13. Alternatively, an aspartic acid at position Ile-404 disrupts the complex, but does not abrogate ubiquitylation. This position is slightly more solvent-exposed and therefore could more reasonably accommodate a carboxylate group. In addition, a charged residue is sometimes found at this position. For example, the U-box domain of CHIP has a lysine in this position, and it is the aliphatic carbons of this side chain that interact with Ubc13. Finally, I439D abolishes complex formation as well as ubiquitylation. In this position, the negatively charged carboxylate group must be solvent-exposed, and the only solvent access is toward the Ubc13 binding site. This would effectively abrogate binding with Ubc13.

RNF8 May Contact Donor Ubiquitin

Our structural information also provides implications about the mechanism of RNF8-driven ubiquitylation. The crystal structures of other E2/E3 complexes with ubiquitin have revealed that many E3 enzymes may contact both the E2 and the ubiquitin. For example, both the E3 enzymes Rabex-5 and the HECT domain of NEDD4L contact ubiquitin in different ways, possibly to position ubiquitin into a catalytically favorable position (40–42). In addition, it has been shown that Ubc13/Mms2 alone can form Lys-63-linked polyubiquitin chains without the participation of an E3 (43). It is possible that an E3 ligase is required simply to increase the rate of the reaction. In their crystal structure of ubiquitin covalently bound to Ubc13 C87S/Mms2, Eddins et al. showed that the Ubc13/Mms2 heterodimer is poised to form the Lys-63-isopeptide bond between ubiquitin units. They show that the Lys-63 of a noncovalently bound acceptor ubiquitin is aligned to attack the C terminus of the donor ubiquitin (17). The authors suggest that the covalently bound donor ubiquitin is flexibly tethered to Ubc13, and indeed, alternative donor ubiquitin orientations are observed in other covalent E2∼Ub crystal structures (41, 44–46). Alignment of the crystal structure of the covalent Ub∼Ubc13/Mms2 structure with our ternary structure of RNF8 indicates potential contact between RNF8 and the flexible ubiquitin molecule. Lys-432, Arg-433, and Lys-434 (KRK) on α2 of RNF8 (Fig. 2B) form a positive patch that would clash with Lys-6 and Lys-11 in β1 and β2 of ubiquitin as it is positioned in the Eddins et al. structure, thus requiring a change in the ubiquitin orientation. We speculate that upon binding of the RNF8 to Ubc13/Mms2, the RING domain makes contact with the covalently bound ubiquitin, orienting the donor ubiquitin in a manner that enhances its reactivity for nucleophilic attack by the Lys-63 of the acceptor ubiquitin. Because Ubc13 is primarily charged with monoubiquitin, this mode of catalysis is consistent with the idea that RING domains catalyze the formation of ubiquitin chains by sequentially adding a single ubiquitin monomer at a time (47).

The Role of the RNF8 Coiled-coil

Although coiled-coils have been predicted in RING domain-containing proteins previously (8, 9), we have presented the first crystal structure of a homodimeric RING domain stabilized by a coiled-coil. A question that remains concerns the specific role of the coiled-coil and dimerization of RNF8. One role appears to be to stabilize the RNF8 RING domain for interactions with Ubc13; however, other roles are also possible. For example, an overall dimeric oligomeric state of RNF8 could allow the two forkhead-associated domains of the dimer to interact with different phosphorylated protein partners. Indeed, the RNF8 forkhead-associated domain not only interacts with MDC1, but also binds phosphorylated HERC2, a HECT E3 ligase, and RNF8 is required for the participation of both MDC1 and HERC2 in HR (48). It is also possible that both protomers within the RNF8 dimer may participate more directly in the catalysis of ubiquitylation. For example, another dimeric RING E3, RNF4, uses one RING to contact its E2, UbcH5a, whereas the other RING domain appears to contact the covalently attached donor ubiquitin directly (35). Although such a mechanism is formally possible in the RNF8-Ubc13 system, it would require a significant shift in the orientation of the donor ubiquitin from that observed in the Ub∼Ubc13/Mms2 crystal structure (17). Thus, it may be that RNF8 dimerization is essential for the optimal function of both its forkhead-associated and RING domains.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Grochulski, S. Labiuk, and J. Gorin at the Canadian Light Source beamline 08ID-1 (Saskatoon, SK) and S. Classen at the SYBILS beamline (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA) for assisting in the collection of our diffraction data. We also thank Laila Yermekbayeva for protein expression and Lissete Crombet for plasmid cloning services of RNF168.

This work was supported by a research grant from the Canadian Cancer Society.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 4EPO) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- HR

- homologous recombination

- MALLS

- multiangle laser light scattering

- MDC1

- mediator of DNA damage checkpoint 1

- MIU

- motif that interacts with ubiquitin

- OTUB1

- OTU domain ubiquitin binding 1

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- RAP80

- receptor-associated protein 80

- RING

- really interesting new gene

- RNF8

- ring finger protein 8

- RNF168

- ring finger protein 168

- SEC

- size exclusion chromatography

- ZnF

- zinc finger.

REFERENCES

- 1. Huang L. C., Clarkin K. C., Wahl G. M. (1996) Sensitivity and selectivity of the DNA damage sensor responsible for activating p53-dependent G1 arrest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 4827–4832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ciccia A., Elledge S. J. (2010) The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol. Cell 40, 179–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lukas J., Lukas C., Bartek J. (2011) More than just a focus: the chromatin response to DNA damage and its role in genome integrity maintenance. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 1161–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stucki M., Clapperton J. A., Mohammad D., Yaffe M. B., Smerdon S. J., Jackson S. P. (2005) MDC1 directly binds phosphorylated histone H2AX to regulate cellular responses to DNA double-strand breaks. Cell 123, 1213–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huen M. S., Grant R., Manke I., Minn K., Yu X., Yaffe M. B., Chen J. (2007) RNF8 transduces the DNA-damage signal via histone ubiquitylation and checkpoint protein assembly. Cell 131, 901–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mailand N., Bekker-Jensen S., Faustrup H., Melander F., Bartek J., Lukas C., Lukas J. (2007) RNF8 ubiquitylates histones at DNA double-strand breaks and promotes assembly of repair proteins. Cell 131, 887–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kolas N. K., Chapman J. R., Nakada S., Ylanko J., Chahwan R., Sweeney F. D., Panier S., Mendez M., Wildenhain J., Thomson T. M., Pelletier L., Jackson S. P., Durocher D. (2007) Orchestration of the DNA-damage response by the RNF8 ubiquitin ligase. Science, 318, 1637–1640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang B., Elledge S. J. (2007) Ubc13/Rnf8 ubiquitin ligases control foci formation of the Rap80/Abraxas/Brca1/Brcc36 complex in response to DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 104, 20759–20763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Doil C., Mailand N., Bekker-Jensen S., Menard P., Larsen D. H., Pepperkok R., Ellenberg J., Panier S., Durocher D., Bartek J., Lukas J., Lukas C. (2009) RNF168 binds and amplifies ubiquitin conjugates on damaged chromosomes to allow accumulation of repair proteins. Cell 136, 435–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stewart G. S., Panier S., Townsend K., Al-Hakim A. K., Kolas N. K., Miller E. S., Nakada S., Ylanko J., Olivarius S., Mendez M., Oldreive C., Wildenhain J., Tagliaferro A., Pelletier L., Taubenheim N., Durandy A., Byrd P. J., Stankovic T., Taylor A. M., Durocher D. (2009) The RIDDLE syndrome protein mediates a ubiquitin-dependent signaling cascade at sites of DNA damage. Cell 136, 420–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim H., Huang J., Chen J. (2007) CCDC98 is a BRCA1-BRCT domain-binding protein involved in the DNA damage response. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 710–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu Z., Wu J., Yu X. (2007) CCDC98 targets BRCA1 to DNA damage sites. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 716–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang B., Matsuoka S., Ballif B. A., Zhang D., Smogorzewska A., Gygi S. P., Elledge S. J. (2007) Abraxas and RAP80 form a BRCA1 protein complex required for the DNA damage response. Science 316, 1194–1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nakada S., Tai I., Panier S., Al-Hakim A., Iemura S., Juang Y. C., O'Donnell L., Kumakubo A., Munro M., Sicheri F., Gingras A. C., Natsume T., Suda T., Durocher D. (2010) Noncanonical inhibition of DNA damage-dependent ubiquitination by OTUB1. Nature 466, 941–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. VanDemark A. P., Hofmann R. M., Tsui C., Pickart C. M., Wolberger C. (2001) Molecular insights into polyubiquitin chain assembly: crystal structure of the Mms2/Ubc13 heterodimer. Cell 105, 711–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moraes T. F., Edwards R. A., McKenna S., Pastushok L., Xiao W., Glover J. N., Ellison M. J. (2001) Crystal structure of the human ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme complex, hMms2-hUbc13. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 669–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eddins M. J., Carlile C. M., Gomez K. M., Pickart C. M., Wolberger C. (2006) Mms2-Ubc13 covalently bound to ubiquitin reveals the structural basis of linkage-specific polyubiquitin chain formation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 915–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McKenna S., Moraes T., Pastushok L., Ptak C., Xiao W., Spyracopoulos L., Ellison M. J. (2003) An NMR-based model of the ubiquitin-bound human ubiquitin conjugation complex Mms2.Ubc13: the structural basis for lysine 63 chain catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 13151–13158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McKenna S., Spyracopoulos L., Moraes T., Pastushok L., Ptak C., Xiao W., Ellison M. J. (2001) Noncovalent interaction between ubiquitin and the human DNA repair protein Mms2 is required for Ubc13-mediated polyubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 40120–40126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yin Q., Lin S. C., Lamothe B., Lu M., Lo Y. C., Hura G., Zheng L., Rich R. L., Campos A. D., Myszka D. G., Lenardo M. J., Darnay B. G., Wu H. (2009) E2 interaction and dimerization in the crystal structure of TRAF6. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 658–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang M., Windheim M., Roe S. M., Peggie M., Cohen P., Prodromou C., Pearl L. H. (2005) Chaperoned ubiquitylation: crystal structures of the CHIP U box E3 ubiquitin ligase and a CHIP-Ubc13-Uev1a complex. Mol. Cell 20, 525–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wiener R., Zhang X., Wang T., Wolberger C. (2012) The mechanism of OTUB1-mediated inhibition of ubiquitination. Nature 483, 618–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Juang Y. C., Landry M. C., Sanches M., Vittal V., Leung C. C., Ceccarelli D. F., Mateo A. R., Pruneda J. N., Mao D. Y., Szilard R. K., Orlicky S., Munro M., Brzovic P. S., Klevit R. E., Sicheri F., Durocher D. (2012) OTUB1 co-opts Lys48-linked ubiquitin recognition to suppress E2 enzyme function. Mol. Cell 45, 384–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McCoy A. J. (2007) Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 63, 32–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., Richardson J. S., Terwilliger T. C., Zwart P. H. (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grigoryan G., Degrado W. F. (2011) Probing designability via a generalized model of helical bundle geometry. J. Mol. Biol. 405, 1079–1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kabsch W. (1993) Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry and cell constants. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 795–800 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vagin A., Teplyakov A. (2010) Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 22–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cohen S. X., Ben Jelloul M., Long F., Vagin A., Knipscheer P., Lebbink J., Sixma T. K., Lamzin V. S., Murshudov G. N., Perrakis A. (2008) ARP/wARP and molecular replacement: the next generation. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 64, 49–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Winn M. D., Isupov M. N., Murshudov G. N. (2001) Use of TLS parameters to model anisotropic displacements in macromolecular refinement. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 57, 122–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Plans V., Scheper J., Soler M., Loukili N., Okano Y., Thomson T. M. (2006) The RING finger protein RNF8 recruits UBC13 for lysine 63-based self- polyubiquitylation. J. Cell. Biochem. 97, 572–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brzovic P. S., Rajagopal P., Hoyt D. W., King M. C., Klevit R. E. (2001) Structure of a BRCA1-BARD1 heterodimeric RING-RING complex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 833–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hibbert R. G., Huang A., Boelens R., Sixma T. K. (2011) E3 ligase Rad18 promotes monoubiquitination rather than ubiquitin chain formation by E2 enzyme Rad6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 5590–5595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Plechanovová A., Jaffray E. G., McMahon S. A., Johnson K. A., Navrátilová I., Naismith J. H., Hay R. T. (2011) Mechanism of ubiquitylation by dimeric RING ligase RNF4. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 1052–1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zheng N., Wang P., Jeffrey P. D., Pavletich N. P. (2000) Structure of a c-Cbl-UbcH7 complex: RING domain function in ubiquitin-protein ligases. Cell 102, 533–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lok G. T., Sy S. M., Dong S. S., Ching Y. P., Tsao S. W., Thomson T. M., Huen M. S. (2012) Differential regulation of RNF8-mediated Lys-48- and Lys-63-based polyubiquitylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 196–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lovering R., Hanson I. M., Borden K. L., Martin S., O'Reilly N. J., Evan G. I., Rahman D., Pappin D. J., Trowsdale J., Freemont P. S. (1993) Identification and preliminary characterization of a protein motif related to the zinc finger. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 2112–2116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sato Y., Yoshikawa A., Mimura H., Yamashita M., Yamagata A., Fukai S. (2009) Structural basis for specific recognition of Lys-63-linked polyubiquitin chains by tandem UIMs of RAP80. EMBO J. 28, 2461–2468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Penengo L., Mapelli M., Murachelli A. G., Confalonieri S., Magri L., Musacchio A., Di Fiore P. P., Polo S., Schneider T. R. (2006) Crystal structure of the ubiquitin binding domains of rabex-5 reveals two modes of interaction with ubiquitin. Cell 124, 1183–1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kamadurai H. B., Souphron J., Scott D. C., Duda D. M., Miller D. J., Stringer D., Piper R. C., Schulman B. A. (2009) Insights into ubiquitin transfer cascades from a structure of a UbcH5B approximately ubiquitin-HECT(NEDD4L) complex. Mol. Cell 36, 1095–1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee S., Tsai Y. C., Mattera R., Smith W. J., Kostelansky M. S., Weissman A. M., Bonifacino J. S., Hurley J. H. (2006) Structural basis for ubiquitin recognition and autoubiquitination by Rabex-5. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 264–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hofmann R. M., Pickart C. M. (1999) Noncanonical MMS2-encoded ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme functions in assembly of novel polyubiquitin chains for DNA repair. Cell 96, 645–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Serniwka S. A., Shaw G. S. (2009) The structure of the UbcH8-ubiquitin complex shows a unique ubiquitin interaction site. Biochemistry, 48, 12169–12179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hamilton K. S., Ellison M. J., Barber K. R., Williams R. S., Huzil J. T., McKenna S., Ptak C., Glover M., Shaw G. S. (2001) Structure of a conjugating enzyme-ubiquitin thiolester intermediate reveals a novel role for the ubiquitin tail. Structure 9, 897–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sakata E., Satoh T., Yamamoto S., Yamaguchi Y., Yagi-Utsumi M., Kurimoto E., Tanaka K., Wakatsuki S., Kato K. (2010) Crystal structure of UbcH5b∼ubiquitin intermediate: insight into the formation of the self-assembled E2∼Ub conjugates. Structure 18, 138–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pierce N. W., Kleiger G., Shan S. O., Deshaies R. J. (2009) Detection of sequential polyubiquitylation on a millisecond timescale. Nature 462, 615–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bekker-Jensen S., Rendtlew Danielsen J., Fugger K., Gromova I., Nerstedt A., Lukas C., Bartek J., Lukas J., Mailand N. (2010) HERC2 coordinates ubiquitin-dependent assembly of DNA repair factors on damaged chromosomes. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 80–86; supp. pp. 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]