Background: Misfolded proteins are degraded via the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway or form aggregates that are cleared by autophagy.

Results: Several yeast ubiquitin ligases protect against aggregate formation and promote aggregate clearance.

Conclusion: A ubiquitin ligase network influences proteostasis by controlling degradation, proteasome regulation, and autophagy.

Significance: Investigating ubiquitin ligase function is important for understanding aggregate formation and clearance.

Keywords: Aggregation, Hsp90, Molecular Chaperone, Proteasome, Protein Kinases, Ubiquitin Ligase, Cytosolic Quality Control, Proteostasis

Abstract

Quality control ubiquitin ligases promote degradation of misfolded proteins by the proteasome. If the capacity of the ubiquitin/proteasome system is exceeded, then misfolded proteins accumulate in aggregates that are cleared by the autophagic system. To identify components of the ubiquitin/proteasome system that protect against aggregation, we analyzed a GFP-tagged protein kinase, Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP, in yeast strains deleted for 14 different ubiquitin ligases. We show that deletion of almost all of these ligases affected the proteostatic balance in untreated cells such that Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregation was changed significantly compared with the levels found in wild type cells. By contrast, aggregation was increased significantly in only six E3 deletion strains when Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP folding was impaired due to inhibition of the molecular chaperone Hsp90 with geldanamycin. The increase in aggregation of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP due to deletion of UBR1 and UFD4 was partially suppressed by deletion of UBR2 due to up-regulation of Rpn4, which controls proteasome activity. Deletion of UBR1 in combination with LTN1, UFD4, or DOA10 led to a marked hypersensitivity to azetidine 2-carboxylic acid, suggesting some redundancy in the networks of quality control ubiquitin ligases. Finally, we show that Ubr1 promotes clearance of protein aggregates when the autophagic system is inactivated. These results provide insight into the mechanics by which ubiquitin ligases cooperate and provide feedback regulation in the clearance of misfolded proteins.

Introduction

Protein quality control processes regulate the folding and degradation of nascent and misfolded proteins. Three distinct cellular machineries regulate such processes, including molecular chaperones, the ubiquitin/proteasome system (UPS),3 and the autophagic system. Whether a misfolded protein is degraded or whether it aggregates depends on the capacity of the UPS to promote efficient degradation. If the UPS capacity is exceeded, then aggregates of misfolded proteins accumulate (1, 2). In mammalian cells, such aggregates or aggresomes contain misfolded proteins, molecular chaperones, and components of the UPS (3). In yeast, distinct aggregate compartments form that are either mobile and ubiquitylated with a juxtanuclear localization (juxtanuclear quality control compartment (JUNQ)), or immobile and non-ubiquitylated (insoluble protein deposit (IPOD)) (4). The JUNQ compartment contains misfolded proteins that can rapidly exchange with the cytosolic environment, which, combined with their ubiquitylation status, suggests they can be substrates for proteasomal degradation. In contrast, the relatively immobile IPOD aggregate compartments lack ubiquitylated proteins and may be cleared via the autophagic system. More recently, additional compartments containing aggregated proteins have been defined on the basis of their interaction with the small heat shock protein, Hsp42 (5). Hsp42 incorporates into aggregates that exist in a more peripheral localization compared with those that are juxtanuclear and yet are distinct from IPOD compartments containing the prion Rnq1. Furthermore, Hsp42 is required for the formation of the peripheral compartments.

The specific role of the UPS in quality control processes depends in part on a growing number of quality control ubiquitin ligases that catalyze ubiquitylation of misfolded proteins. Several ubiquitin ligases, including Hrd1, Doa10, and Rma1, among others, act at the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum to catalyze ubiquitylation of misfolded membrane proteins or proteins destined for secretion (6). Others act in the cytosol to clear misfolded proteins, including the C terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein (CHIP), Cul5, Hul5, Ltn1, Ufd4, Ubr1, the N-recognin and Ubr2 that is important for degradation of N-end rule substrates (7–15). There is some crossover between cytosolic and endoplasmic reticulum quality control pathways because CHIP can function in endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation, and Doa10 catalyzes ubiquitylation of misfolded cytosolic proteins (16, 17). In addition, San1 acts in the nucleus for quality control of misfolded nuclear proteins and for destruction of misfolded proteins that are translocated into the nucleus just for that purpose (13, 18).

The role of molecular chaperones in the quality control process is to promote folding or degradation of nascent or misfolded proteins. How such fate determinations are made is not clear, although it seems likely to depend on the folding potential of the client. The role of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone in such triage decisions has been exploited for therapeutic benefit with several small molecule inhibitors in clinical trials for a variety of tumors (19). These small molecules act by competitively inhibiting the ATPase activity of Hsp90, which is important for the reaction cycle that recruits unfolded proteins from specific co-chaperones and promotes their subsequent folding. Small molecule inhibitors, such as geldanamycin, block client folding and reprogram Hsp90 to promote client protein degradation via the UPS. How the reprogramming occurs is uncertain, but it appears to involve recruitment of ubiquitin ligases, such as CHIP, Cul5, and UBR1 (20, 21). In preclinical models of breast cancer, Hsp90 inhibitors also induce client protein aggregation, especially for overexpressed oncogenes, such as ErbB2 (22).

The cellular response to misfolded protein accumulation is adaptive and results in the increased expression of both molecular chaperone and UPS arms of the quality control process. Molecular chaperones are induced by a variety of proteotoxic stressors, in an acute manner, by activation of the heat shock transcription factors (1). Likewise, the yeast Rpn4 transcription factor is responsible for induction of proteasome subunits (23) and is induced by acute stress and the presence of misfolded membrane proteins (24, 25). The Rpn4 example is particularly intriguing because its stability is dependent on Ubr2, a ubiquitin ligase that is related to Ubr1 but does not function via the N-end rule degradation pathway (26).

The combined actions of proteins involved in the protein homeostasis or proteostasis network, as described above, lead to a healthy balance of protein folding and disposal of misfolded proteins. Upon aging, there is a decline in the capacity of the proteostasis network to function properly and to maintain this balance. This leads to the toxic accumulation of misfolded proteins that can manifest in several late onset disease states. In this report, we address the roles of several ubiquitin ligases in preventing the accumulation of misfolded protein aggregates and in their clearance once formed. We demonstrate that several ubiquitin ligases function together in a network and that Ubr2 acts in a distinct manner to suppress aggregate formation upon proteostatic imbalance.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Yeast Strains, Media, and Chemicals

Yeast strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Gene disruptions were obtained by PCR from the Yeast Knock-out Collection (27). Yeast cultures were grown in YPD medium or in selective dropout medium according to standard protocols (28). Where necessary, G418 sulfate from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA) and nourseothricin from Werner BioAgents (Jena, Germany), were added to a final concentration of 400 and 100 μg/ml, respectively. For the spot tests, single colonies from fresh plates were used in 10-fold serial dilutions in sterile water, and the plates were grown at 30 °C. Geldanamycin (GA) was obtained from Invivogen (San Diego, CA), MG132 was from EMD Chemicals (Gibbstown, NJ), and l-azetidine-2-carboxylic acid (AZC) and cycloheximide were from Sigma.

TABLE 1.

Genotypes of strains used in this study

| Genotype | Source |

|---|---|

| BY4741, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3), pRS423 GAL1 Rnq1mRFP (HIS) | This study |

| BY4741, ubr1::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, ubr2::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, ubr1::kanMX6, ubr2::HIS3, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, san1::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, erg6::natMX4, pRS416 GPD His-Ste11ΔNK444R (URA3) | Ref. 14 |

| BY4741, ubr1::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS416 GPD His-Ste11ΔNK444R (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, ubr1::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3), pYEplac181 (LEU2) | This study |

| BY4741, ubr1::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3), pYEplac181 FLAG-MR1(LEU2) | This study |

| BY4741, ubr1::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3), pYEplac181 FLAG-UBR1 (LEU2) | This study |

| BY4741, erg6::natMX4, pRS416 GPD His-Ste11ΔNK444R (URA3), pPGK-Ub-Pro-LacZ (LEU2) | This study |

| BY4741, ubr1::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS416 GPD His-Ste11ΔNK444R (URA3), pPGK-Ub-Pro-LacZ (LEU2) | This study |

| BY4741, ubr2::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS416 GPD His-Ste11ΔNK444R (URA3), pPGK-Ub-Pro-LacZ (LEU2) | This study |

| BY4741, ubr1::kanMX6, ubr2::HIS3, erg6::natMX4, pRS416 GPD His-Ste11ΔNK444R (URA3), pPGK-Ub-Pro-LacZ (LEU2) | This study |

| BY4741, san1::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS416 GPD His-Ste11ΔNK444R (URA3), pPGK-Ub-Pro-LacZ (LEU2) | This study |

| BY4741, rpn4::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, rpn4::kanMX6, ubr2::HIS3, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, bre1::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, dia2::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, doa10::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, hrd1::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, hul5::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, ltn1::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, pib1::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, pex10::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, rmd5::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, tom1::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, ufd4::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, doa10::kanMX6, ubr1::LEU2, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, ltn1::kanMX6, ubr1::LEU2, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, ufd4::kanMX6, ubr1::LEU2, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, ufd4::kanMX6, ubr2::HIS3, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, ubc4::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, ubc5::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, rad6::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, doa10::kanMX6, ubr1::LEU2, erg6::natMX4, pRS416 GPD His-Ste11ΔNK444R (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, ltn1::kanMX6, ubr1::LEU2, erg6::natMX4, pRS416 GPD His-Ste11ΔNK444R (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, ufd4::kanMX6, ubr1::LEU2, erg6::natMX4, pRS416 GPD His-Ste11ΔNK444R (URA3) | This study |

| S288C, Rpn4-TT | Open Biosystems |

| S288C, Rpn4-TT, ubr2::kanMX6 | This study |

| S288C, Rpn4-TT, erg6::natMX4 | This study |

| S288C, Rpn4-TT, ubr2::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4 | This study |

| BY4741, pep4::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, pep4::kanMX6, ubr1::LEU2, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, atg5::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

| BY4741, hsp104::kanMX6, erg6::natMX4, pRS316 GAL1 Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (URA3) | This study |

Construction of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP and Fluorescence Microscopy

A 0.7-kb GFP fragment from YEpS3gFp (gift from Dr. JP Hirsch) was ligated to NotI/SacII sites of pRS316 GAL1 plasmid, resulting in pRS316 GAL1 GFP plasmid. Ste11ΔNK444R was PCR-amplified from p416GPDHis-Ste11ΔNK444R (gift from Dr. J. L. Johnson) and subcloned to SpeI/NotI sites of pRS316 GAL1 GFP, resulting in pRS316 GAL1 ste11ΔNK444R-GFP plasmid (Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP). Yeast strains containing Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP were grown overnight in SD medium containing glucose and then transferred into SD medium containing 2% raffinose, followed by induction using 2% galactose. An A600 of 3 was collected for each sample from the galactose cell suspension and was treated with GA or DMSO for 1 h in a nutator at 30 °C. 15 min before the end of the incubation time, Hoechst 33258 (Invitrogen) at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml was added to the cells to stain the DNA. For the microscopy chase experiments, after the 1-h treatment with GA, MG132 (100 μm) and/or cycloheximide (200 μg/ml) was added, and images were taken at different times. Cells were viewed with a Nikon inverted fluorescence microscope, Eclipse Ti-E, under the ×60 objective. Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP was viewed using the FITC filter, and Hoechst-stained nuclei were viewed using the DAPI filter. Quantifications were done using the Volocity software by PerkinElmer Life Sciences.

Aggregation Assay and Western Blot Analysis

Yeast cells were grown to log phase, and an A600 of 6 was collected for each sample. Cells were pelleted down by centrifuging for 3 min at 3000 rpm and resuspended in 200 μl of selective SD medium. Cells were then treated with DMSO or GA (50 μm) and incubated in a 30 °C rotator for 1 h. Cells were then collected by centrifugation. The cell pellets were resuspended in 250 μl of lysis buffer (0.1% Nonidet P-40, 50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mm EDTA, 1% glycerol, 1 mm PMSF, and 1× protease inhibitor EDTA-free mixture; Roche Applied Science) and were added into prechilled glass beads (0.5 mm) in 0.5-ml Eppendorf tubes. The cells were lysed in a bead beater at 4 °C with two 30-s bursts with a 30-s interval in between. The tubes were pierced with a 25-gauge needle, and the extract was eluted by centrifugation for 1 min at 2000 rpm. The supernatant was transferred into new tubes and was centrifuged for 1 min at 3000 rpm. The supernatant was again collected and transferred into new tubes and centrifuged for 15 min at 15,000 × g. After centrifugation, the soluble fraction (supernatant) was removed and transferred into new tubes. The insoluble fraction (pellet) was washed twice with 400 μl of wash buffer (2% Nonidet P-40, 50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mm EDTA, and 1% glycerol) and centrifuged for 15 min at 15,000 × g. After the washes, the insoluble fraction was resuspended in lysis buffer, and 2× SDS sample buffer was added to the same volume in both soluble and insoluble fraction samples. The samples were then boiled for 5 min, and equal volumes were analyzed in 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, as described previously (29). Antibodies used were anti-HIS (Sigma), anti-PGK1, anti-GFP (Invitrogen), and anti-β-gal (Promega, Madison, WI). Western blots, if necessary, were quantified using a Licor Odyssey Infrared imaging system. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism software (version 4; GraphPad).

RNA Extraction and Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from 15-ml cultures of an A600 1–2, using the method of Schmitt et al. (30). Removal of residual contaminating DNA was achieved using the RNase-free DNase kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Primers for LacZ and Act1 were designed using the LightCycler Probe Design 2 software. One-step RT-PCRs were performed using a homemade 2× RTB buffer containing 100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 20 mm KCl, 10 mm (NH4)2SO4, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.2% Tween 20, 0.2 mg/ml non-acetylated BSA (Sigma-Aldrich). The final reaction mix also contained 1:30,000 SYBR Green (Molecular Probes, Inc., Carlsbad, CA), Transcriptor Reverse Transcriptase (24 units/ml; Roche Applied Science), Protector RNase Inhibitor (60 units/ml; Roche Applied Science), and FastStart Taq DNA Polymerase (50 units/ml; Roche Applied Science). The reactions were assembled in a 10-μl total volume and run in the LightCycler 2.0 system (Roche Applied Science). Analysis of the products was done with LightCycler software version 4.1 using the ACT1 gene as a reference.

β-Galactosidase Assay

Yeast cultures were grown, from an overnight culture, in SD medium to log phase. Cells were harvested and washed once with water. The cell pellets were resuspended in 200 μl of extract buffer (20 mm Hepes-KOH, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, 5 mm DTT, 1 mm PMSF, and 1× protease inhibitor EDTA-free mixture; Roche Applied Science) and were added into prechilled glass beads (0.5 mm) in 0.5-ml Eppendorf tubes. The cells were lysed in a bead beater at 4 °C, with two 25-s bursts with a 25-s interval in between. The tubes were pierced with a 25-gauge needle, and the extract was eluted by centrifugation for 10 min at 4 °C. Assays for β-galactosidase activity were performed using 20 μl of protein extract and 780 μl of Z buffer (60 mm Na2HPO4·7H2O, 40 mm NaH2PO4·H2O, 10 mm KCl, 1 mm MgSO4·7H2O, and 50 mm β-mercaptoethanol). Reactions were started by the addition of 200 μl of a 4 mg/ml solution of o-nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside (in 0.1 m NaPO4 buffer, pH 7.0). The reactions were incubated for 60 min at 30 °C. The β-galactosidase activity was determined by measuring the absorbance at A420 in a Beckman DU 650 spectrophotometer. The absorbance at A420 was normalized to the protein content as determined by the Bradford assay, and the results were graphed as a percentage of the wild type. Assays were done in triplicate to determine S.E.

Pulse-Chase Analysis

The pulse-chase analysis to measure Rpn4 half-life was performed as described (31) using a pulse labeling time of 3 min.

RESULTS

Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP Aggregation Can Be Stimulated by Hsp90 Inhibition or Expression of RNQ1

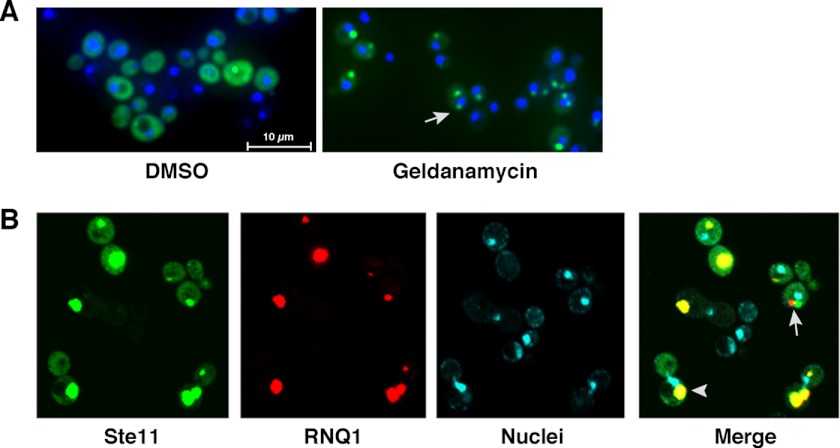

We developed an inducible model to study the function of the quality control apparatus in protein aggregation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The model utilizes a GFP fusion with a protein kinase that serves as a reporter for protein stability and aggregation. The protein kinase construct is a previously reported catalytically inactive kinase domain of Ste11 (Ste11ΔNK444R) that still requires the Hsp90 chaperone machinery for proper folding (14, 32). We prepared a GFP fusion with Ste11ΔNK444R (Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP) and expressed it to a high level from a galactose-inducible promoter. Expression of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP in wild type yeast resulted in diffuse fluorescence with the occasional puncta (Fig. 1A, left). Upon treatment of the cells with the Hsp90 inhibitor, GA, there was a change in the appearance of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP from diffuse to largely punctate, with one to two and occasionally more puncta per cell (Fig. 1A, right). Notably, some of the puncta formed in a juxtanuclear location (Fig. 1A, right, arrow), whereas others were more peripheral, similar to those quality control deposition sites described previously by others (4, 5). Importantly, simultaneous treatment of the translation inhibitor, cycloheximide, with GA resulted in the complete absence of puncta of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP, suggesting that the observed aggregation was specific to newly made proteins (not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Hsp90 inhibition with GA or expression of RNQ1 promotes aggregation of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP in the cytosol. A, WT cells expressing Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP under the control of the GAL1-10 promoter were treated with DMSO (left) or 25 μm GA (right) for 1 h. The nuclei were visualized by Hoechst staining. Images were collected using a Nikon Inverted Eclipse Ti epifluorescence microscope from live yeast cells with a ×60 dry lens. Image overlay was performed using ImageJ software. B, WT cells co-expressing Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (green) and RNQ1-mRFP (red) under the control of the GAL1-10 promoter. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst. The Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregates colocalized (arrowhead) or not (arrow) with the Rnq1 aggregates.

We next examined whether the Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregates were related to those formed by the prion protein Rnq1 (33). The rationale for this approach was based on previous studies that showed that the peripheral aggregates may represent IPOD aggregates that contain a mixture of both prion and non-prion proteins, as described in one study (4), or a distinct quality control compartment, as described more recently by Specht et al. (5). Surprisingly, expression of RNQ1 led to a profound shift toward Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregation even in the absence of geldanamycin. These aggregates largely overlapped with the prion aggregates (Fig. 1B, arrowhead), but not always (Fig. 1B, arrow). Our model for protein quality control using Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP therefore has some unique properties because its aggregation state is influenced by Hsp90 inhibition and prion expression. The latter finding is of great significance because it has been observed previously that expression of RNQ1 is required for aggregation of polyglutamine and formation of other yeast prions, such as [PSI+] and [URE3] (33, 34). This is the first example where RNQ1 expression influences the aggregation state of a protein not normally associated with aggregate formation.

Ubr1 and Ubr2 Have Opposing Roles in Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP Aggregation

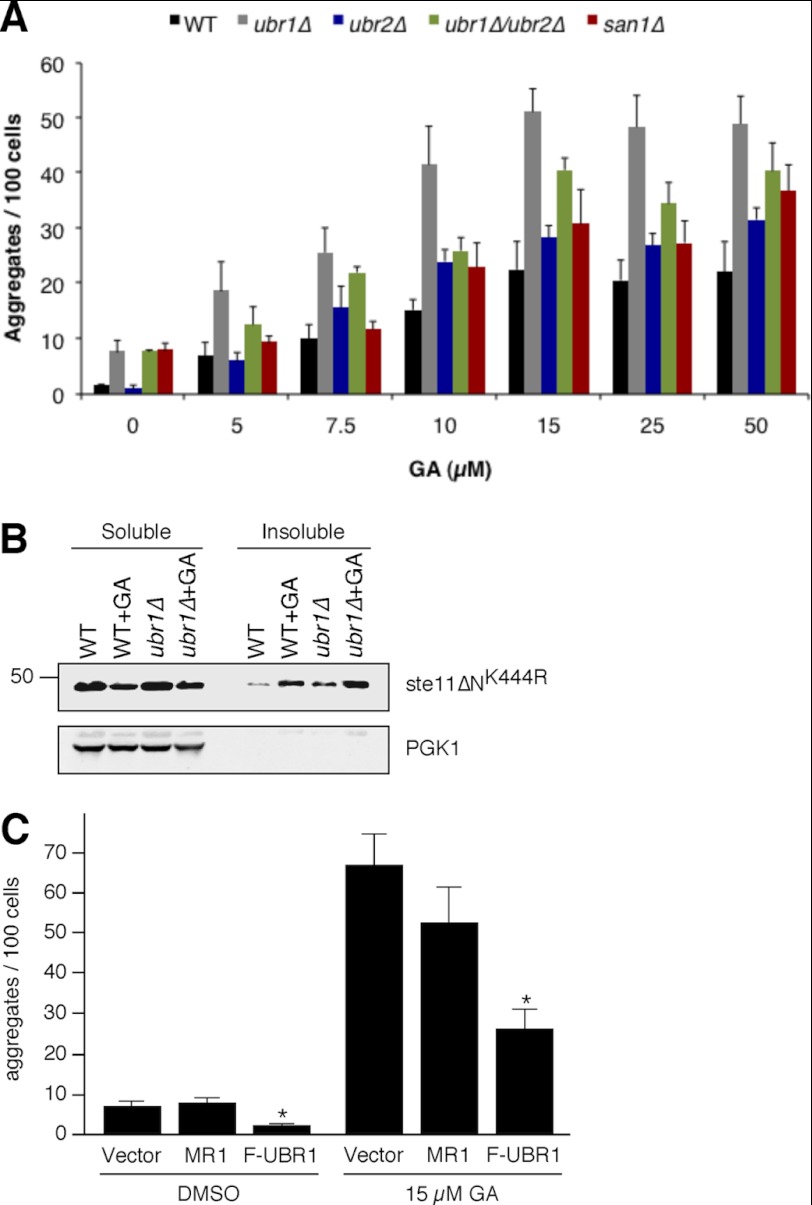

We reported recently that Ubr1, Ubr2, and San1 ubiquitin ligases were important for the degradation of several protein kinases, including Ste11ΔNK444R, upon Hsp90 inhibition with GA or in cells expressing a mutant form of the kinase-specific co-chaperone CDC37 (14). As noted above, however, there is also considerable aggregation of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP upon Hsp90 inhibition. To determine whether Ubr1, Ubr2, or San1 protected cells against protein kinase aggregation, we assayed the effect of GA treatment on the appearance of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregates in cells deleted for each ubiquitin ligase (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Ubr1 protects against aggregate formation. A, WT cells or cells deleted for different E3 ligases expressing Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP were treated with different concentrations of GA or DMSO for 1 h. Aggregates were counted in several hundred cells as visualized by Hoechst. The quantification was performed using Volocity software (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The graph shows the number of aggregates formed per 100 cells (n = 3; error bars, S.E.). B, WT and ubr1Δ cells expressing Ste11ΔNK444R from the GPD promoter were treated with DMSO or 50 μm GA for 1 h. Shown is Western blot analysis of protein extracts prepared using 0.1% Nonidet P-40. The soluble and insoluble fractions were separated at 15,000 × g for 15 min. C, ubr1Δ strains overexpressing wild type UBR1 (F-UBR1), a RING domain UBR1 mutant (MR1), or the empty vector were analyzed for formation of aggregates. The graph shows the quantification of the results from three independent experiments (error bars, S.E.). The difference between the number of aggregates in ubr1Δ cells expressing only the empty vector and ubr1Δ cells expressing F-UBR1 is statistically significant in the presence and in the absence of GA (nonparametric t test; *, p = 0.05).

We first determined the concentration dependence for GA-induced Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregation. The number of puncta were quantified from several hundred cells for each condition and expressed as the number of aggregates per 100 cells. Hoechst staining was used to visualize the nuclei, and our calculations were based on one nucleus per cell. This approach demonstrated that for wild type cells, the effect saturated at 15 μm GA with ∼22% of cells containing aggregates (Fig. 2A).

When a GA titration experiment was performed in the E3 deletion cells, the most profound effect was observed in the ubr1Δ mutant (Fig. 2A). In this case, there was a ∼5-fold increase in the number of puncta even without GA treatment compared with wild type cells (from 1.5 to 7.5 aggregates/100 cells). In the presence of GA, there was a 2-fold increase in the number of puncta at all concentrations tested, from 5 to 50 μm. By contrast, deletion of UBR2 had little effect by itself on Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregation upon GA treatment, although there was a small decrease in the number of puncta in the absence of GA compared with wild type cells (from 1.5 to 0.9 aggregates/100 cells). However, deleting UBR2 in the ubr1Δ mutant had the surprising effect of partially suppressing the ubr1Δ phenotype with respect to puncta formation in the presence of GA. In all cases, the number of puncta in ubr1Δ/ubr2Δ double mutants was intermediate between the number found in ubr1Δ GA-treated cells and ubr2Δ GA-treated cells. The role of San1 ubiquitin ligase was also determined, but the number of puncta that formed in san1Δ cells was only slightly greater compared with WT at most concentrations of GA except for the highest amount used at 50 μm.

Although we observed differences in the formation of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregates in these mutant strains as described above, the kinase was expressed in similar amounts in all strains (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B). Furthermore, each of the mutant strains exhibited similar growth characteristics in the absence and presence of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP expression (supplemental Fig. S1C).

We confirmed the role of Ubr1 in protecting against Ste11ΔNK444R aggregation using biochemical fractionation. For these experiments, we determined the amount of Nonidet P-40-insoluble Ste11ΔNK444R in GA-treated cells by Western blot. The results of these experiments showed a strong correlation between the decrease in soluble Ste11ΔNK444R and increased insoluble Ste11ΔNK444R upon GA treatment of wild type cells (Fig. 2B). In addition, there was a large increase in the amount of Nonidet P-40-insoluble Ste11ΔNK444R in ubr1Δ cells.

The contribution of Ubr1 to Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP quality control was further investigated by overexpressing UBR1 in the ubr1Δ mutant (Fig. 2C). In this case, the number of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregates that formed in the presence of GA was reduced to levels normally observed in wild type cells, confirming the UBR1 dependence of the phenotype. This finding also demonstrates that aggregate formation is limited by factors other than Ubr1 concentration because there is no further reduction beyond the levels observed in the wild type strain upon UBR1 overexpression. However, the increase in the number of aggregates observed in ubr1Δ cells is a reflection of the loss of Ubr1 catalytic activity. This was determined by expressing a catalytically inactive form of UBR1 (MR1; C1220S (35)). In this case, there was very little reduction in the amount of puncta induced by GA treatment compared with ubr1Δ alone with an empty vector (Fig. 2C).

In summary, inhibition of Hsp90 promotes degradation and aggregation of newly synthesized Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP, and Ubr1 appears to have a protective role in preventing aggregate formation, probably by aiding in the disposal of the misfolded kinase. UBR2 deletion by itself does not affect aggregate formation to a large extent, although it acts to partially compensate for the loss of UBR1.

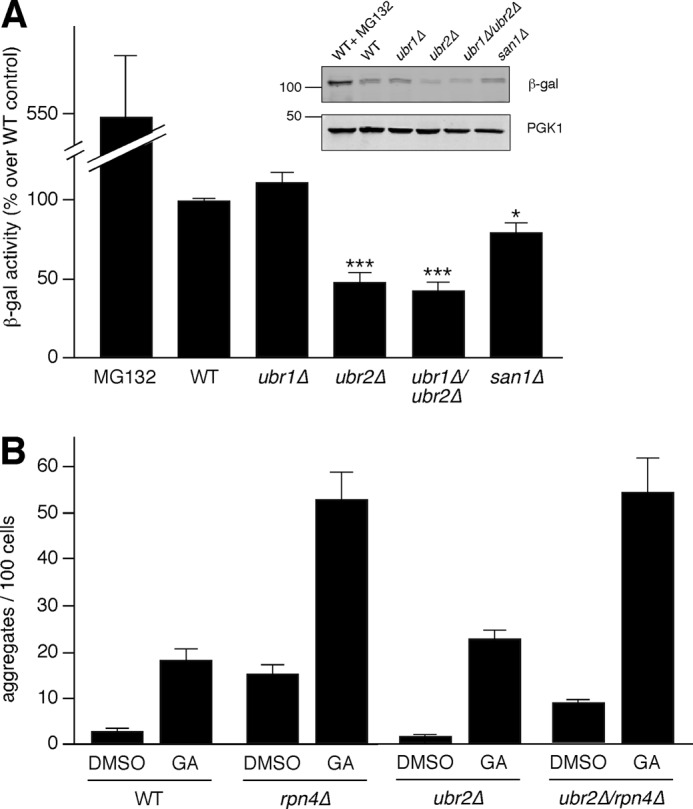

Formation of Misfolded Protein Aggregates Is Controlled by Rpn4

Ubr2 has an important role in the quality control network by regulating the stability of Rpn4, which modulates the expression of genes encoding proteasome subunits (26). As described above (Fig. 2A), deletion of UBR2 led to partial suppression of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP in the absence of UBR1. One possible explanation is that deletion of UBR2 led to increased proteasome concentration even in the ubr1Δ strain, and this resulted in partial suppression of aggregate formation in the ubr1Δ/ubr2Δ double mutant as compared with the ubr1Δ alone (Fig. 1B). As a first step toward testing this hypothesis, we analyzed proteasome activity in ubr1Δ cells that were also deleted for UBR2. This was accomplished by measuring the activity of an unstable form of LacZ, Ub-Pro-βGal (36). As expected, we observed a significant decrease in β-galactosidase activity and protein levels in cells deleted for UBR2 (Fig. 3A), although there was a similar amount of Ub-Pro-βGal mRNA from all strains tested, including ubr2Δ (supplemental Fig. S2A). This increase in proteasome activity was also observed in the ubr1Δ/ubr2Δ strain, thereby correlating the increase in proteasome activity with a decrease in aggregate formation in ubr1Δ/ubr2Δ double mutant cells compared with ubr1Δ alone. We further tested whether the ubr2Δ phenotype was directly dependent on Rpn4. As shown in Fig. 3B, deletion of RPN4 led to a large increase in Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregation compared with wild type cells in the presence of GA. Furthermore, this increase occurred to a similar extent in ubr2Δ/rpn4Δ double mutants (Fig. 3B), strongly supporting the hypothesis that Ubr2 modulated Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregation via its effects on Rpn4 stability.

FIGURE 3.

Increased proteasomal function in ubr2Δ strains, via Rpn4 stabilization, correlates with a decrease in aggregate formation. A, a Ub-Pro-LacZ reporter was analyzed for proteasome function in WT, ubr1Δ, ubr2Δ, ubr1Δ/ubr2Δ, and san1Δ strains. As a control, WT cells were treated with 50 μm MG132 for 1 h before cell lysis. The graph shows β-galactosidase activity, as a percentage of WT, in the indicated strains (n = 6; error bars, S.E.; ***, p ≤ 0.0001; *, p ≤ 0.05). Inset, Western blot analysis of Ub-Pro-LacZ correlates with β-galactosidase activity. B, WT, rpn4Δ, ubr2Δ, and ubr2Δ/rpn4Δ strains expressing Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP were treated with 15 μm GA for 1 h (n = 4; error bars, S.E.).

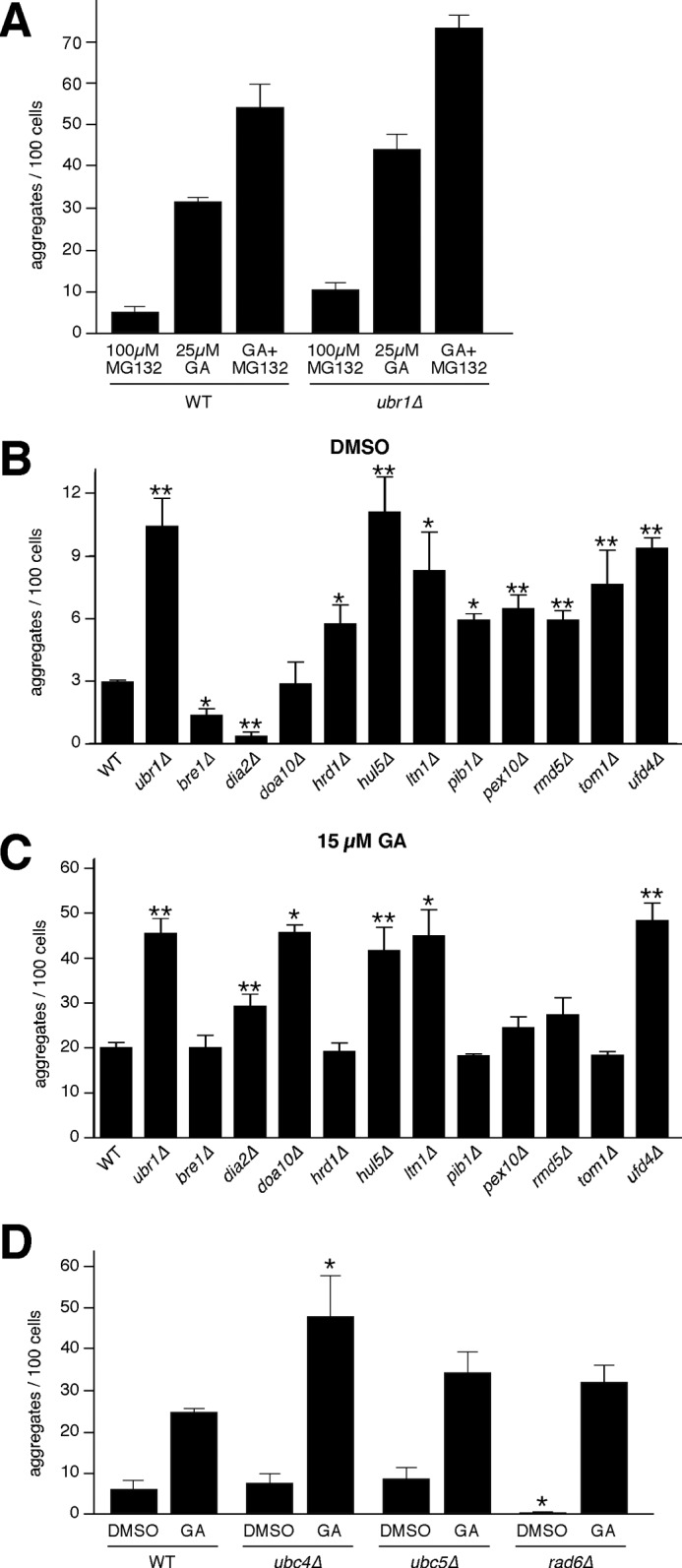

A Network of Ubiquitin Ligases Protects against Aggregate Formation and Is Cytoprotective

We sought to determine if Ubr1 played a predominant role in protecting against Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregation or whether other E3s contributed to the machinery that limits aggregate formation. As a first step, we established an upper limit for aggregate formation by inhibiting the proteasome with MG132, using a concentration that is known to prevent degradation of misfolded protein kinases (14). In GA-treated wild type cells, proteasome inhibition led to increased aggregate formation by ∼1.7-fold compared with GA-treated cells alone (Fig. 4A). A similar increase was recorded in the ubr1Δ mutant, suggesting that other components of the UPS, besides Ubr1, contribute to protecting against aggregate formation. We therefore analyzed the role of 11 different ubiquitin ligases for their ability to modulate formation of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregates in the absence and presence of GA. Several of these E3s have been shown previously to function in quality control processes, including, Doa10, Hrd1, Hul5, Ltn1, Rmd5, and Ufd4 (9, 15, 16, 37, 38), whereas others, including Bre1, Dia2, Pib1, Pex10, and Tom1, have not. In the absence of GA, there was an increase in Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregate formation in all of the deletion strains with the exception of bre1Δ, dia2Δ, and doa10Δ compared with the wild type (Fig. 4B). This shows that perturbation in many different cellular degradation systems leads to an increase in basal levels of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP probably due to imbalance in the UPS. By contrast, aggregate formation in the presence of GA was specific to a more selected group of quality control E3s, including Doa10, Hul5, Ltn1, and Ufd4 (Fig. 4C). This group also included Dia2, although the increase in Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregation was weaker in this strain than for the others. The levels to which Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregated in each of these deletion mutants were similar to those observed for deletion of UBR1.

FIGURE 4.

Function of quality control E3s and E2s in protecting against aggregate formation. A, WT and ubr1Δ cells expressing Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP were treated with 100 μm MG132, 25 μm GA, or both compounds for 1 h. Pictures were taken with the epifluorescence microscope and quantified using Volocity software (n = 3; error bars, S.E.). The additive effect of MG132 and GA in accumulation of aggregates in both WT and ubr1Δ strains suggests involvement of other E3s. B, different E3s were tested for aggregate formation in the presence of DMSO for 1 h. WT and ubr1Δ cells were used as controls (n ≥ 3; error bars, S.E.; non-parametric t test; *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01). C, as in B, only the strains were treated with 15 μm GA for 1 h. D, cells deleted for different E2s were tested for aggregate formation after 1 h of treatment with 15 μm GA or DMSO. The graph represents the quantified results of three independent experiments and the statistical analysis using a nonparametric t test (n = 3; error bars, S.E.; *, p = 0.05).

E2 enzymes related to the actions of Ubr1 and Ufd4 were also required for proper clearance of misfolded Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP (Fig. 4D). In this case, following GA treatment, there was a statistically significant effect of deleting UBC4 (39) but not UBC5 or RAD6, which is known to function with Ubr1 and Ubr2. The lack of effect of deleting RAD6 may reflect its competing role in promoting clearance of misfolded proteins via Ubr1 and in ubiquitylation of Rpn4, via Ubr2, which controls proteasome expression (26, 35). This may explain why we observed reduced levels of basal Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregation in the rad6Δ mutant in comparison with untreated wild type cells (Fig. 4D).

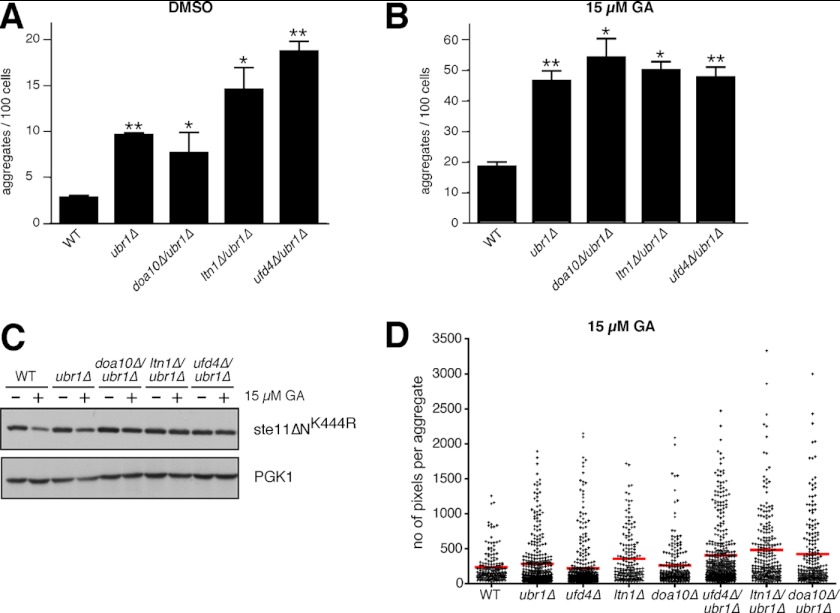

We prepared double mutants of ubr1Δ with several of the quality control E3s described above to assess whether they work redundantly to prevent aggregation. These double mutants, which included doa10Δ/ubr1Δ, ltn1Δ/ubr1Δ, and ufd4Δ/ubr1Δ, were analyzed in the absence and presence of GA (we constructed an hul5Δ/ubr1Δ mutant, but it failed to propagate under the conditions necessary for Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP expression). In the absence of GA, doa10Δ/ubr1Δ, ltn1Δ/ubr1Δ, and ufd4Δ/ubr1Δ mutants all displayed enhanced levels of aggregated Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP compared with the wild type. These levels were especially enhanced in the ufd4Δ/ubr1Δ double mutant because the levels of uninduced Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP rose to levels observed in GA-treated wild type cells (Fig. 5, compare A with B). In contrast, the number of aggregates observed after GA treatment was not significantly different for the double mutants compared with the ubr1Δ mutant alone (∼50 puncta/100 cells; Fig. 5B), although Western blot analysis showed that there was almost complete inhibition of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP degradation in the double mutant strains treated with GA (Fig. 5C). Although it was unexpected that the numbers of aggregates in the double mutants would be similar compared with the ubr1Δ mutant alone, we did observe an increase in the range of sizes for the Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregates, as measured by pixels per aggregate. As shown in Fig. 5D, the range of aggregate size in ubr1Δ, ufd4Δ, ltn1Δ, and doa10Δ mutants was greater than that observed in wild type cells, although the mean size is not that much different for any of the single mutant strains. The range in aggregate size was further increased in double mutants between ubr1Δ and ufd4Δ or ltn1Δ or doa10Δ. Furthermore, there was an increase in the mean aggregate size by 1.7–2-fold compared with the wild type in these double mutants (Fig. 5D).

FIGURE 5.

Effects of double E3 deletions on aggregate formation and size. A, double mutants between ubr1Δ and doa10Δ, ltn1Δ, or ufd4Δ were tested for aggregate formation after 1 h of treatment with DMSO. The results were quantified and graphed as previously (n ≥ 3; error bars, S.E.; non-parametric t test; *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01). WT and ubr1Δ cells were used as controls. The double mutants ubr1Δ/ltn1Δ and ubr1Δ/ufd4Δ appear to form more aggregates than WT or ubr1Δ cells under normal conditions (DMSO). B, as in A except that the strains were treated with 15 μm GA for 1 h. None of the double mutants tested had substantially more aggregates/100 cells than the ubr1Δ strain after GA treatment. C, WT, ubr1Δ, doa10Δ/ubr1Δ, ltn1Δ/ubr1Δ, and ufd4Δ/ubr1Δ cells expressing Ste11ΔNK444R from the GPD promoter were treated with DMSO or 15 μm GA for 1 h. Western blot analysis of protein extracts prepared using 1% SDS. PGK1 is used as a loading control. D, the size (number of pixels) of aggregates from WT, ubr1Δ, ufd4Δ, ltn1Δ, doa10Δ, and their double mutants with ubr1Δ after treatment with 15 μm GA for 1 h is presented in a dot plot. Each dot corresponds to the size of one aggregate, whereas the average size of the aggregates for each strain is shown with a red line. All aggregates from two different experiments are plotted. Mean size values are 237.2 pixels for WT, 285.7 pixels for ubr1Δ, 223.0 pixels for ufd4Δ, 358.6 pixels for ltn1Δ, 261.0 pixels for doa10Δ, 405.5 pixels for ubr1Δ/ufd4Δ, 481.7 pixels for ubr1Δ/ltn1Δ, and 426.5 pixels for ubr1Δ/doa10Δ cells.

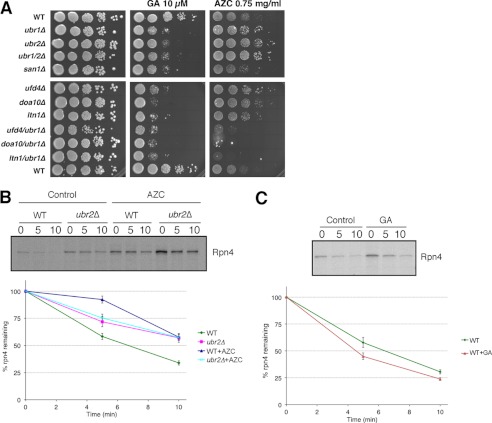

Accumulation of misfolded proteins can be toxic, although there is currently some debate about the cytoprotective nature of large protein aggregates (40). We therefore tested whether the ubiquitin ligases under study were cytoprotective under conditions that promoted protein misfolding. Two agents of protein misfolding were used for these experiments: GA, to inhibit Hsp90 and cause misfolding of Hsp90 clients including protein kinases, and azetidine 2-carboxylic acid, a proline analog that competitively incorporates with l-proline and results in a more general stress response (41, 42). Deletion of DOA10, LTN1, SAN1, UBR1, or UBR2 resulted in a greater sensitivity to GA compared with the wild type (Fig. 6A). Importantly, the double mutants failed to display any further sensitivity at the concentration of GA tested (e.g. doa10Δ versus doa10Δ/ubr1Δ in Fig. 6A), suggesting that each has distinct and perhaps non-overlapping substrate specificities. By contrast, plating the same strains on AZC resulted in markedly different outcomes that were strain-specific. Notably, the ubr2Δ strain showed a strong resistance to AZC compared with the wild type. Other single deletion mutants that also displayed greater resistance to AZC compared with the wild type included ubr1Δ, doa10Δ, ufd4Δ, and ltn1Δ to a lesser degree. The san1Δ mutant had a similar sensitivity to the wild type strain. Furthermore, and in contrast to the behavior of the single mutants, double mutants of ubr1Δ with any of doa10Δ, ltn1Δ, or ufd4Δ resulted in hypersensitivity to AZC, suggesting that they function together in redundant pathways under conditions of a general proteotoxic stress.

FIGURE 6.

Effects of GA and AZC on cell growth, Rpn4 induction, and stability. A, 10-fold serial dilutions of cells were spotted on plates containing YPD medium with or without 10 μm GA and 0.75 mg/ml AZC. The plates were grown at 30 °C for 3 days and then photographed. B, pulse-chase analysis of TAP-tagged Rpn4 in WT and ubr2Δ cells in the presence or absence of AZC. The cells were treated with 50 mm AZC for 45 min, labeled with 100 μCi/ml [35S]methionine for 3 min, and chased with the addition of cold methionine and cycloheximide for 5 and 10 min. Rpn4-TAP was immunoprecipitated using TAP antibody and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The graph shows the quantification of six independent pulse-chase experiments by a PhosphorImager to determine the degradation rate of Rpn4-TAP (n = 6; error bars, S.E.). C, pulse-chase analysis of TAP-tagged Rpn4 in WT cells in the presence or absence of 50 μm GA. The pulse-chase experiment was done as in B. The graph represents the quantified results of six independent pulse-chase experiments (n = 6; error bars, S.E.).

The resistance of the ubr2Δ mutant to AZC (Fig. 6) may reflect increased proteasomal activity (e.g. Fig. 3) via stabilized Rpn4. Indeed, we observed induction and Ubr2-dependent stabilization of Rpn4 in the presence of AZC (Fig. 6B), similar to the findings of others using canavanine (43). Rpn4 was also induced by GA treatment but not stabilized (Fig. 6C), and this did not lead to any difference in growth sensitivity of the ubr2Δ strain compared with other E3 deletion mutants (Fig. 6A). These findings suggest that the growth suppression phenotype of the ubr2Δ and ubr1Δ mutants may result from factors that might operate independently of or perhaps in addition to, in the case of ubr2Δ, increased proteasome activity.

A Role for Ubiquitin Ligases and the Proteasome in the Clearance of Aggregated Proteins

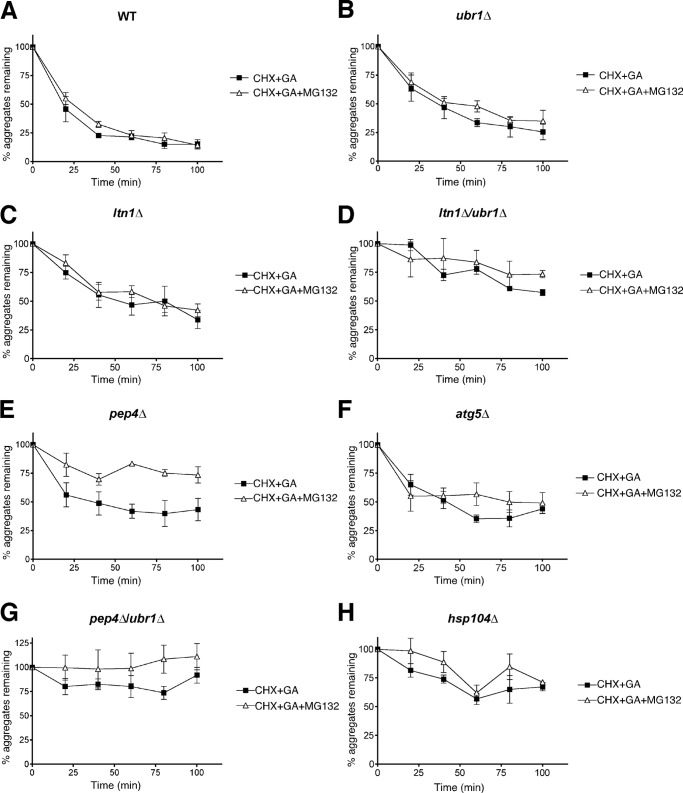

Previous studies suggested that JUNQ or perinuclear quality control compartments contain ubiquitylated proteins that might undergo reversible aggregation. Such a finding is significant in view of the ability of Hsp104 to facilitate solubilization and refolding of aggregated proteins (44). By contrast, it is also commonly accepted that aggregated proteins can be cleared by the autophagic system via digestion in the lysosome/vacuole (33), which in mammalian cells can be facilitated by ubiquitylation (45). We therefore sought to examine the mechanisms that lead to the clearance of aggregated forms of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP. For these experiments, we analyzed the fate of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregates in GA-treated cells after cycloheximide treatment to prevent further synthesis. After a chase period of 100 min, the percentage of aggregates that remained in wild type cells was reduced to ∼10% of the value when the cycloheximide was added, with a t½ of less than 25 min (Fig. 7A, WT). Proteasome inhibition with MG132 did not change the kinetics of clearance, suggesting that the aggregates were not dissolved via the UPS or that the autophagic system could compensate for loss of UPS function. Clearance of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregates in cells deleted for UBR1 or LTN1 occurred at a slightly reduced rate compared with the wild type strain, and proteasome inhibition had no further effect (Fig. 7, B and C). The roles of Ubr1 and Ltn1 were probed further by examining a double mutant (Fig. 7D). In this case, notably, there was a strong reduction in aggregate clearance, and ∼70% of the aggregates formed initially remained after 100 min. Because MG132 treatment seemed not to affect aggregate clearance in ubr1Δ or ltn1Δ mutants any further, our findings suggest that these two E3s act redundantly in aggregate clearance but in a manner that is independent of the proteasome.

FIGURE 7.

Clearance of aggregates by proteasomal and vacuolar degradation. WT (A), ubr1Δ (B), ltn1Δ (C), ltn1Δ/ubr1Δ (D), pep4Δ (E), atg5Δ (F), pep4Δ/ubr1Δ (G), and hsp104Δ (H) cells expressing Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP were treated with 25 μm GA for 1 h to form aggregates. The fate of the aggregates was followed by the addition of cycloheximide at 200 μg/ml with or without 100 μm MG132. Images of the aggregates were collected and quantified as previously (n = 3; error bars, S.E.).

The mechanism by which Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregates are cleared was further investigated using strains deleted in genes that are part of the vacuolar digestion and autophagic systems. We first determined the rate of aggregate clearance upon deletion of PEP4, the protease that is responsible for activating other proteases that would be involved in aggregate digestion in the vacuole after autophagy (46). In pep4Δ cells, there was reduced aggregate clearance by itself, but this effect was strongly enhanced upon proteasome inhibition with MG132 (Fig. 7E). These findings suggest that proteasomes can act in aggregate clearance as a bypass pathway when vacuolar degradation is blocked. In a mutant deleted for ATG5, which controls formation of autophagosomes, there was a similar reduction in aggregate clearance as was found in the pep4Δ mutant (Fig. 7F). However, in this case, there was no effect of MG132 compared with the pep4Δ mutant, perhaps due to the existence of other autophagasome formation pathways that operate in an atg5Δ mutant (47).

The findings presented thus far suggest that some E3s can act via the autophagic pathway but that a bypass pathway involving the proteasome also exists. Further analysis suggested that Ubr1 could act in both pathways because mutants that are deleted for both PEP4 and UBR1 displayed almost complete inhibition of aggregate clearance (Fig. 7G).

The existence of an aggregate clearance pathway that depends on the UPS and perhaps multiple routes to the vacuole suggests that the disaggregating function of Hsp104 might be involved. This appears to be case based on our experiments because there is a sharp reduction in the clearance of aggregates in an hsp104Δ mutant (Fig. 7H).

DISCUSSION

Quality control pathways decline during aging, and this correlates with the onset of several neurodegenerative conditions that are associated with accumulation of protein aggregates (48). In contrast, stabilization or overexpression of factors that promote quality control, such as the transcription factors that regulate expression of molecular chaperones or proteasome subunits, increases longevity or replicative life span (22, 36, 49). Furthermore, genetic manipulation of Caenorhabditis elegans that results in life span extension led to reduced toxicity and aggregation of polyglutamine (15). What has been generally unclear is how different components of the UPS contribute to the protection against aggregate accumulation. In this report, we identify several ubiquitin ligases that have distinct roles in protecting against accumulation of misfolded proteins into aggregates and against acute proteotoxic stress.

We described in this work a new model for analysis of protein quality control, Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP. Our model is unique in that its aggregated state is drug-inducible via inhibition of Hsp90. A second notable feature of this model protein is its ability to be influenced by expression of the prion, RNQ1. Expression of RNQ1 led to a shift toward the aggregated state of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP even under conditions of normal Hsp90 function, suggesting that its conformation is sensitive to the proteostatic health of the cell. This conclusion was supported by the observation that basal levels of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregates increased significantly in strains deleted for 10 different ubiquitin ligases.

In contrast to the rather general effects of perturbing the proteostasis network on basal Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregation, there was a great deal of specificity with which E3s affected aggregation upon acute inhibition of Hsp90 with GA. The E3s involved in this process include several that were found previously to act in quality control processes, including Doa10, Hul5, Ufd4, and Ubr1 (7–15, 38). In addition, we have characterized a new role for Ltn1, which was found to ubiquitylate nascent proteins synthesized in the absence of a stop codon (9), and for the F-box protein, Dia2, which regulates transcription (50). Importantly, these ubiquitin ligases localize to different cellular compartments, suggesting the existence of distinct targeting mechanisms that have yet to be identified and characterized.

The Ubr2 ubiquitin ligase has a role that contrasts with those of these other E3s described above because its capacity to regulate Rpn4 stability (26) results in a distinct phenotype. In this case, deletion of UBR2 leads to Rpn4 stabilization and increased proteasome activity, and this correlates with a decrease in the number of aggregates that accumulate in the ubr1Δ mutant (Figs. 1 and 3). A similar finding was made for the ufd4Δ mutant that is also deleted for UBR2. In this case, we observed a decrease in Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregation in the double mutant compared with the ufd4Δ mutant alone (supplemental Fig. S2B). Furthermore, deletion of RPN4 by itself leads to a large increase in the aggregation of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP, as might be expected under conditions of reduced proteasome expression (Fig. 3B). Our findings therefore suggest that increasing proteasome activity can, to a limited extent, suppress the loss of function of ubiquitin ligases. This would be consistent with a recent report showing that deletion of UBR2 promotes the replicative life span of yeast in an Rpn4-dependent fashion (36).

Based on these combined findings, however, we would have expected that deletion of UBR2 by itself should affect the number of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregates that form upon Hsp90 inhibition with GA. However, as shown in Fig. 2A, the number of aggregates in the ubr2Δ mutant was similar to the number observed in wild type cells. By contrast, the low levels of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP that form in untreated cells were reduced in the ubr2Δ mutant and also upon deletion of the Ubr2 E2 enzyme, RAD6. These findings suggest a model in which increased proteasome concentration can suppress basal aggregation that might occur in a stochastic manner upon protein overexpression (the example being Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP in our case) or AZC treatment (Fig. 6) or that might occur upon aging. However, an acute stress that leads to a large amount of protein aggregation, such as GA treatment, seems to be largely insensitive to increased proteasome concentration until a certain threshold is reached. Such a threshold in our studies appears to occur when the levels of accumulated misfolded protein increase in cells deleted for E3s in the cytosolic quality control network, including UBR1 or UFD4 among others.

The ability of Doa10, Ltn1, Ufd4, and Ubr1 to protect the cells against aggregate formation upon Hsp90 inhibition was further reflected in their role of protecting against a more general proteotoxic stress caused by AZC treatment. A clear redundancy in ubiquitin ligase action was observed in this case, and cells deleted for UBR1 in addition to any of DOA10, LTN1, or UFD4 displayed hypersensitivity to growth on AZC compared with the wild type. Strikingly, the partial resistance of the single mutants to AZC treatment was unexpected and at this time difficult to fully explain. One possibility is that quality control E3s act to eliminate proteins whose folding potential still exists. In this case, elimination of a single E3 results in a decreased degradation and increased levels of proteins that escape triage to fold properly. We observed this previously for ubr1Δ mutants in cells with poorly folding protein kinases, and in at least one case, we observed an increase in protein kinase activity for Tpk2 even when its folding was compromised in a cdc37 mutant strain (14).

In addition to acting to protect cells against aggregate formation, Ubr1 appears to play a role in the clearance of aggregated Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP. This action does not appear to be the primary source of aggregate removal because the autophagy/vacuolar system appears to be responsible for this. Instead, Ubr1 action was only important in a pep4Δ mutant, where vacuolar degradation was inhibited (46). The likelihood is that Ubr1 action in aggregate clearance is integrated into the disaggregating actions of the Hsp104/Hsp70 bichaperone system (Fig. 7) (44). However, the ability of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP aggregates to be cleared by either the autophagic or a UPS-dependent pathway suggests that the aggregates themselves have attributes of both JUNQ and IPOD compartments (4), which seems clear based on their positioning within the cell and their co-localization with [RNQ+] (Fig. 1). We therefore speculate that inhibition of vacuolar proteases results in accumulation of Ste11ΔNK444R-GFP in quality control compartments that maintain their ability to be cleared by the proteasome in an Ubr1-dependent manner.

In summary, our findings demonstrate the existence of a network of ubiquitin ligases with partial overlapping function that protect cells against accumulation of protein aggregates and acute proteotoxic stress. The inclusion of Ltn1 in this cohort of E3s, whose mouse homolog has a role in protecting against neurodegeneration, suggests that the E3 network may play a large role in the etiology of late onset diseases. By contrast, Ubr2 acts in a distinct and opposite capacity to regulate aggregation via its role in controlling Rpn4 abundance. Finally, we have revealed a novel cross-talk between the UPS and the autophagic systems in yeast for the clearance of misfolded proteins through the actions of Ubr1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Navdeep Kaur for technical assistance and Rasheda Sultana for comments on the manuscript. We also thank Drs. Doug Cyr, Jeanne Hirsch, Jill Johnson, Susan Michaelis, and Youming Xie for plasmids.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants U54CA132378 and NCRR 5G12-RR03060 (to City College of New York).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- UPS

- ubiquitin/proteasome system

- IPOD

- insoluble protein deposit

- AZC

- l-azetidine-2-carboxylic acid

- JUNQ

- juxtanuclear quality control compartment

- CHIP

- C terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein

- TAP

- tandem affinity purification.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hartl F. U., Bracher A., Hayer-Hartl M. (2011) Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature 475, 324–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tyedmers J., Mogk A., Bukau B. (2010) Cellular strategies for controlling protein aggregation. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 777–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnston J. A., Ward C. L., Kopito R. R. (1998) Aggresomes. A cellular response to misfolded proteins. J. Cell Biol. 143, 1883–1898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kaganovich D., Kopito R., Frydman J. (2008) Misfolded proteins partition between two distinct quality control compartments. Nature 454, 1088–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Specht S., Miller S. B., Mogk A., Bukau B. (2011) Hsp42 is required for sequestration of protein aggregates into deposition sites in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 195, 617–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vembar S. S., Brodsky J. L. (2008) One step at a time. Endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 944–957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Connell P., Ballinger C. A., Jiang J., Wu Y., Thompson L. J., Höhfeld J., Patterson C. (2001) The co-chaperone CHIP regulates protein triage decisions mediated by heat-shock proteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 93–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meacham G. C., Patterson C., Zhang W., Younger J. M., Cyr D. M. (2001) The Hsc70 co-chaperone CHIP targets immature CFTR for proteasomal degradation. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 100–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bengtson M. H., Joazeiro C. A. (2010) Role of a ribosome-associated E3 ubiquitin ligase in protein quality control. Nature 467, 470–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ehrlich E. S., Wang T., Luo K., Xiao Z., Niewiadomska A. M., Martinez T., Xu W., Neckers L., Yu X. F. (2009) Regulation of Hsp90 client proteins by a Cullin5-RING E3 ubiquitin ligase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 20330–20335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Johnson E. S., Ma P. C., Ota I. M., Varshavsky A. (1995) A proteolytic pathway that recognizes ubiquitin as a degradation signal. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 17442–17456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eisele F., Wolf D. H. (2008) Degradation of misfolded protein in the cytoplasm is mediated by the ubiquitin ligase Ubr1. FEBS Lett. 582, 4143–4146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heck J. W., Cheung S. K., Hampton R. Y. (2010) Cytoplasmic protein quality control degradation mediated by parallel actions of the E3 ubiquitin ligases Ubr1 and San1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1106–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nillegoda N. B., Theodoraki M. A., Mandal A. K., Mayo K. J., Ren H. Y., Sultana R., Wu K., Johnson J., Cyr D. M., Caplan A. J. (2010) Ubr1 and Ubr2 function in a quality control pathway for degradation of unfolded cytosolic proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 2102–2116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fang N. N., Ng A. H., Measday V., Mayor T. (2011) Hul5 HECT ubiquitin ligase plays a major role in the ubiquitylation and turnover of cytosolic misfolded proteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 1344–1352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Metzger M. B., Maurer M. J., Dancy B. M., Michaelis S. (2008) Degradation of a cytosolic protein requires endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation machinery. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 32302–32316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Younger J. M., Ren H. Y., Chen L., Fan C. Y., Fields A., Patterson C., Cyr D. M. (2004) A foldable CFTRδF508 biogenic intermediate accumulates upon inhibition of the Hsc70-CHIP E3 ubiquitin ligase. J. Cell Biol. 167, 1075–1085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Prasad R., Kawaguchi S., Ng D. T. (2010) A nucleus-based quality control mechanism for cytosolic proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 2117–2127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Trepel J., Mollapour M., Giaccone G., Neckers L. (2010) Targeting the dynamic HSP90 complex in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 537–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Theodoraki M. A., Caplan A. J. (2012) Quality control and fate determination of Hsp90 client proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 683–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sultana R., Theodoraki M. A., Caplan A. J. (2012) UBR1 promotes protein kinase quality control and sensitizes cells to Hsp90 inhibition. Exp. Cell Res. 318, 53–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marx C., Held J. M., Gibson B. W., Benz C. C. (2010) ErbB2 trafficking and degradation associated with K48 and K63 polyubiquitination. Cancer research 70, 3709–3717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xie Y., Varshavsky A. (2001) RPN4 is a ligand, substrate, and transcriptional regulator of the 26S proteasome. A negative feedback circuit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 3056–3061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Metzger M. B., Michaelis S. (2009) Analysis of quality control substrates in distinct cellular compartments reveals a unique role for Rpn4p in tolerating misfolded membrane proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1006–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hahn J. S., Neef D. W., Thiele D. J. (2006) A stress regulatory network for co-ordinated activation of proteasome expression mediated by yeast heat shock transcription factor. Mol. Microbiol. 60, 240–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang L., Mao X., Ju D., Xie Y. (2004) Rpn4 is a physiological substrate of the Ubr2 ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 55218–55223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brachmann C. B., Davies A., Cost G. J., Caputo E., Li J., Hieter P., Boeke J. D. (1998) Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C. A useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14, 115–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kaiser C., Michaelis S., Mitchell A. (eds) (1994) Methods in Yeast Genetics, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 29. Theodoraki M. A., Kunjappu M., Sternberg D. W., Caplan A. J. (2007) Akt shows variable sensitivity to an Hsp90 inhibitor depending on cell context. Exp. Cell Res. 313, 3851–3858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schmitt M. E., Brown T. A., Trumpower B. L. (1990) A rapid and simple method for preparation of RNA from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 3091–3092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mandal A. K., Theodoraki M. A., Nillegoda N. B., Caplan A. J. (2011) Role of molecular chaperones in biogenesis of the protein kinome. Methods Mol. Biol. 787, 75–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Flom G. A., Lemieszek M., Fortunato E. A., Johnson J. L. (2008) Farnesylation of Ydj1 is required for in vivo interaction with Hsp90 client proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 5249–5258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stein K. C., True H. L. (2011) The [RNQ+] prion. A model of both functional and pathological amyloid. Prion 5, 291–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Meriin A. B., Zhang X., He X., Newnam G. P., Chernoff Y. O., Sherman M. Y. (2002) Huntington toxicity in yeast model depends on polyglutamine aggregation mediated by a prion-like protein Rnq1. J. Cell Biol. 157, 997–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Xie Y., Varshavsky A. (1999) The E2-E3 interaction in the N-end rule pathway. The RING-H2 finger of E3 is required for the synthesis of multiubiquitin chain. EMBO J. 18, 6832–6844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kruegel U., Robison B., Dange T., Kahlert G., Delaney J. R., Kotireddy S., Tsuchiya M., Tsuchiyama S., Murakami C. J., Schleit J., Sutphin G., Carr D., Tar K., Dittmar G., Kaeberlein M., Kennedy B. K., Schmidt M. (2011) Elevated proteasome capacity extends replicative life span in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chu J., Hong N. A., Masuda C. A., Jenkins B. V., Nelms K. A., Goodnow C. C., Glynne R. J., Wu H., Masliah E., Joazeiro C. A., Kay S. A. (2009) A mouse forward genetics screen identifies LISTERIN as an E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in neurodegeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 2097–2103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hwang C. S., Shemorry A., Auerbach D., Varshavsky A. (2010) The N-end rule pathway is mediated by a complex of the RING-type Ubr1 and HECT-type Ufd4 ubiquitin ligases. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 1177–1185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Seufert W., Jentsch S. (1991) Yeast ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes involved in selective protein degradation are essential for cell viability. Acta Biol. Hung. 42, 27–37 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wolfe K. J., Cyr D. M. (2011) Amyloid in neurodegenerative diseases. Friend or foe? Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 476–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Trotter E. W., Berenfeld L., Krause S. A., Petsko G. A., Gray J. V. (2001) Protein misfolding and temperature up-shift cause G1 arrest via a common mechanism dependent on heat shock factor in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 7313–7318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Trotter E. W., Kao C. M., Berenfeld L., Botstein D., Petsko G. A., Gray J. V. (2002) Misfolded proteins are competent to mediate a subset of the responses to heat shock in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 44817–44825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. London M. K., Keck B. I., Ramos P. C., Dohmen R. J. (2004) Regulatory mechanisms controlling biogenesis of ubiquitin and the proteasome. FEBS Lett. 567, 259–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Glover J. R., Lindquist S. (1998) Hsp104, Hsp70, and Hsp40. A novel chaperone system that rescues previously aggregated proteins. Cell 94, 73–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kirkin V., McEwan D. G., Novak I., Dikic I. (2009) A role for ubiquitin in selective autophagy. Mol. Cell 34, 259–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Parr C. L., Keates R. A., Bryksa B. C., Ogawa M., Yada R. Y. (2007) The structure and function of Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteinase A. Yeast 24, 467–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nishida Y., Arakawa S., Fujitani K., Yamaguchi H., Mizuta T., Kanaseki T., Komatsu M., Otsu K., Tsujimoto Y., Shimizu S. (2009) Discovery of Atg5/Atg7-independent alternative macroautophagy. Nature 461, 654–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang Y., Ozawa A., Zaman S., Prasad N. B., Chandrasekharappa S. C., Agarwal S. K., Marx S. J. (2011) The tumor suppressor protein menin inhibits AKT activation by regulating its cellular localization. Cancer Res. 71, 371–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Morley J. F., Morimoto R. I. (2004) Regulation of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans by heat shock factor and molecular chaperones. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 657–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bao M. Z., Schwartz M. A., Cantin G. T., Yates J. R., 3rd, Madhani H. D. (2004) Pheromone-dependent destruction of the Tec1 transcription factor is required for MAP kinase signaling specificity in yeast. Cell 119, 991–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]