Abstract

Purpose

The effectiveness of an opioid rotation to parenteral hydromorphone in advanced cancer patients has never been investigated. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the analgesic efficacy and side effects of parenteral hydromorphone on serious cancer-related pain.

Methods

We included 104 consecutive advanced cancer patients who were extensively pretreated with opioids. They were rotated to parenteral hydromorphone because they failed to achieve adequate pain relief on other opioids. Pain intensity and side effects were daily assessed. The moment of adequate pain control was defined as the first of at least 2 consecutive days when the mean pain intensity at rest was ≤4 (on a 0–10 numeric rating scale) and side effects were tolerable.

Results

The reasons for rotation to parenteral hydromorphone were inadequate pain control with/without expected delivery problems due to high opioid dosages (n = 61) and intolerable side effects with persistent pain (n = 43). Adequate pain control was achieved in 86 patients (83%) within a mean of 5 days. Eight of 86 patients still had side effects, but these were scored as acceptable. The mean pain intensity at rest decreased from 5.4 [standard deviation (sd) = 2.1] to 2.4 (sd = 1.5; p < 0.001). The median failure-free treatment period was 57 days and covered a substantial part of the median survival of 78 days in the responding patients.

Conclusions

In advanced cancer patients with serious unstable cancer-related pain refractory to other opioids, continuous parenteral administration of hydromorphone often results in long-lasting adequate pain control and should be considered even after extensive pretreatment with opioids.

Keywords: Hydromorphone, Pain, Neoplasm, Parenteral infusions, Analgesics, Opioids

Introduction

Pain is a serious problem in patients with advanced solid cancer. Two thirds of these patients experience pain of whom 20% grade their pain as moderate to severe [1]. The World Health Organization set up guidelines for treating chronic cancer pain up to high doses of around-the-clock opioids, striving for an acceptable pain control for the majority of cancer patients [2, 3]. However, despite following these guidelines accurately, 10–30% of patients do not achieve adequate pain relief, mainly because of uncontrolled side effects restraining them from further dose increment [3]. For these patients, an opioid rotation, a change in opioid or route of administration has been shown to be beneficial in several studies [4, 5]. Parenteral administration of opioids (here defined as subcutaneous or intravenous) is especially useful for rapid titration in case of severe pain, but it is also indicated for patients with pain in whom dose escalations are needed to doses that are no longer convenient for oral use [6, 7]. When high doses of opioids are indicated, potent opioids that can still be delivered in small volumes are necessary, especially when subcutaneous administration is desirable [8]. When parenteral treatment fails, more invasive techniques like epidural and intrathecal opioid treatment are possible, although these techniques are more expensive and hazardous [9].

Hydromorphone is a semisynthetic derivate of morphine, with comparable efficacy and side effects to morphine when administrated subcutaneously in low concentrations [10]. Since hydromorphone is more lipophilic than other opioids [10, 11], it can be administrated subcutaneously in highly concentrated solutions, making it particularly useful for subcutaneous administration when high doses of opioids are needed [7, 10, 12]. Based on this knowledge, it can be hypothesized that in case of inadequate pain control and/or uncontrolled side effects in patients who already use opioids in high doses for moderate to severe pain, rotating from a certain opioid to parenteral hydromorphone might be a useful alternative. In practice, this situation will especially occur in cancer patients with progressive disease for whom antitumor therapy is no longer available and life expectancy, therefore, is limited. These patients are also often treated with earlier opioid rotations in an effort to treat pain with tolerable side effects. However, data on the effect of parenteral hydromorphone in such patients are lacking.

We therefore performed a descriptive, retrospective study in extensively pretreated advanced cancer patients with inadequate pain control or uncontrolled side effects on the current opioids who were rotated to parenteral hydromorphone. The objective of this study was to investigate the analgesic efficacy and side effects of opioid rotation to parenteral hydromorphone, continuously administrated, on serious cancer-related pain among this patient population.

Methods

Data were collected in our 13-bed Unit for Palliative Care and Symptom Control (PCSC unit) in the Erasmus MC Daniel den Hoed Cancer Center in the Netherlands. Most of the patients admitted to our PCSC unit have already been set on pain medication by their general practitioner or treating physicians, either from the cancer center or from other hospitals. Patients with severe pain despite the use of around-the-clock opioids or patients who suffer intolerable side effects to the used opioids are admitted for titration of parenteral opioids. At our PCSC unit, we generally use morphine or fentanyl for parenteral administration, depending on the opioid used before. In general, opioid rotation to another opioid is used in case of inadequate pain control combined with limiting opioid-related side effects; otherwise, dose escalation is applied with the opioid in use. Patients who suffer intolerable side effects on morphine and fentanyl and patients with persistent pain despite multiple dose escalations, particularly when high doses of subcutaneous opioids are needed to such an extent that delivery problems (are expected to) occur because of needed volumes, can be rotated to parenteral hydromorphone. The decision for rotating to parenteral hydromorphone is made by our multidisciplinary pain team. In general, patients who are rotated to parenteral hydromorphone start with 50–75% of the equianalgesic dose of the former opioid to allow for incomplete cross tolerance [13]. Published equianalgesic dose tables were used [11, 14, 15]. The subcutaneous route is preferred unless the infusion volume of the opioid administrated per hour is too large. Parenteral hydromorphone is not commercially available in the Netherlands, but can be prepared by our hospital pharmacy in a concentration of 10 mg/ml.

In this retrospective study, consecutive patients with nociceptive pain set on parenteral hydromorphone between December 2004 and June 2010 were included, thereby using the unit’s standard systematic registration of pain intensity and side effects. Baseline characteristics including age, gender, type of cancer, tumor status, antitumor therapy (radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy), prior analgesic prescription, pain intensity, side effects, and the reason for rotation to hydromorphone were obtained from medical records. Reasons for rotation to hydromorphone were classified as inadequate pain control {pain intensity >4 [on a 0–10 numerical rating scale (NRS)] or uncomfortable} often while reaching the maximum feasible volume for subcutaneous administration of morphine or fentanyl, and intolerable (moderate to severe; see next paragraph) opioid-induced side effects (i.e., nausea or vomiting, constipation, confusion, somnolence, hallucinations, and myoclonus). In case of a combination of intolerable side effects and persistent pain or delivery problems of subcutaneous administration of large volumes, the reason for rotation was classified as intolerable side effects.

After starting parenteral administration of hydromorphone, pain intensity and side effects were recorded twice daily. Patients were asked to rate their pain intensity at rest and with movement on the NRS [16]. The mean pain scores were calculated as the means of two pain intensity scores per day for pain at rest and pain with movement separately. Side effects were systematically rated using a Likert scale as none, mild, moderate, or severe. Side effects were further dichotomized into tolerable (none or mild) or intolerable (moderate or severe) categories. The used dosages of the different opioids were converted to oral morphine equivalent daily doses (MED, in milligrams per day) according to published equianalgesic dose tables: oral morphine 60 mg/day = parenteral morphine 20 mg/day = transdermal fentanyl 25 μg/h = parenteral fentanyl 25μg/h = oral oxycodone 30 mg/day = oral hydromorphone 8 mg/day = parenteral hydromorphone 4 mg/day [11, 14, 15].

The effectiveness of continuous administration of parenteral hydromorphone was evaluated by determining the percentage of patients whose pain got adequately controlled with continuous administration of parenteral hydromorphone without intolerable side effects, the change in mean pain intensity at rest and mean pain with movement in these patients, and the time needed to achieve adequate pain control. The moment that adequate pain control was reached was defined as the first day of at least 2 consecutive days in which the mean pain score at rest was 4 or less [17, 18], or in case pain measurement was not reported, patients and physicians were documented to be satisfied both in the absence of intolerable side effects. Moreover, to get an impression of the duration of the effect of parenteral hydromorphone, the failure-free period was determined among all patients who reached adequate pain control after rotation to parenteral hydromorphone. Failure-free period was defined as the period from the start of hydromorphone until death or the application of more invasive techniques. In some patients pain was adequately controlled with dosages of hydromorphone for which rotation back to an oral or transdermal opioid formulation was feasible. These patients were not considered as failures on parenteral hydromorphone and therefore were included in the calculation of the failure-free treatment period. Overall survival was calculated from the start of hydromorphone until death or end of the study.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Science for Windows version 15.0. Descriptive statistics was used to describe patients’ sociodemographic and medical characteristics. Differences in mean pain intensity overtime were tested with the t test. The failure-free treatment period and overall survival was visualized using the Kaplan–Meier method. July 31, 2010 was the censoring date for survival. Reported p values are two tailed, and p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

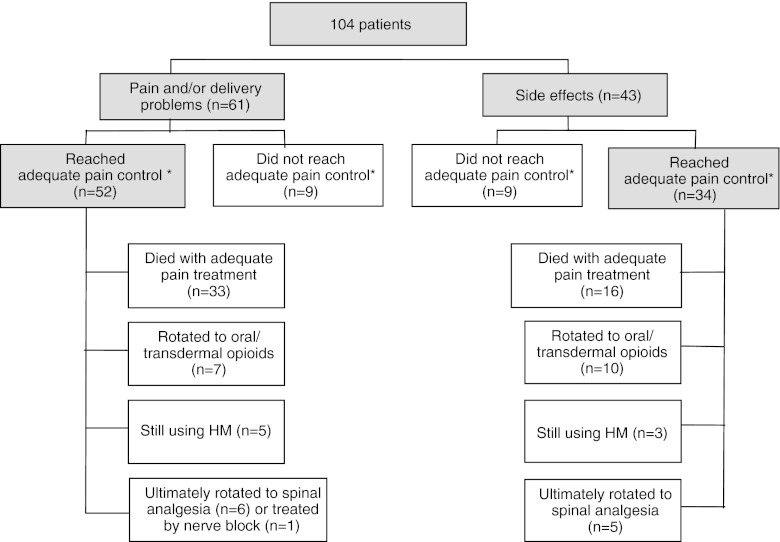

One hundred and four consecutive patients were rotated to hydromorphone between December 2004 and June 2010. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. All patients had advanced cancer, predominantly lung (18%), urological (17%), breast (14%), gastrointestinal (14%), or gynecological carcinoma (9%). The main reasons for rotation to parenteral hydromorphone were inadequate pain control combined with/without expected delivery problems due to high opioid dosages [n = 61, (59%)] and intolerable side effects with persistent pain [n = 43 (41%); Fig. 1].

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Number | |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (sd) | 57 (13.5) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 57 (55%) |

| Female | 47 (45%) |

| Stage of disease | |

| Metastatic disease | 91 (88%) |

| Local recurrence | 13 (13%) |

| More than one pain location | 82 (79%) |

| Anticancer treatment at start hydromorphone | |

| No anticancer therapy | 84 (81%) |

| Radiotherapy (within 2 weeks before start) | 12 (12%) |

| Chemotherapy | 5 (5%) |

| Hormonal therapy | 3 (3%) |

| Use of atc opioids until start hydromorphonea | |

| Oral morphine | 5 (5%) |

| Parenteral morphine | 14 (13%) |

| Transdermal fentanyl | 38 (37%) |

| Parenteral fentanyl | 41 (39%) |

| Oral oxycodone | 6 (6%) |

| Oral hydromorphone | 5 (5%) |

| Oral morphine equianalgesic dose (mg), median (range) | 600 (72–2,592) |

| Atc opioids ever used before hydromorphone | |

| Fentanyl (transdermal or parenteral) | 92 (88%) |

| Morphine (oral or parenteral) | 66 (63%) |

| Oxycodone (oral) | 30 (29%) |

| Tramadol (oral) | 21 (20%) |

| Hydromorphone (oral) | 7 (7%) |

| Methadone (oral) | 1 (1%) |

HM hydromorphone, SD standard deviation, atc around the clock

aFive patients used combination of analgesics

Fig. 1.

Opioid rotation to parenteral hydromorphone: summary of indications and clinical effectiveness. Asterisk indicates adequate pain control = mean pain score in rest ≤4 (or when patients and physicians were satisfied) in the absence of intolerable side effects

All patients had received opioids before the start of parenteral hydromorphone (Table 1); 19 patients (18%) used morphine, and 79 patients (76%) used fentanyl as last opioid before the start of hydromorphone. Patients included in this study had serious cancer-related pain, which became obvious in the fact that most patients were extensively pretreated; 91 patients (88%) had been treated with two or more opioid rotations (drug and/or route) before rotating to hydromorphone. In addition, before rotating to parenteral hydromorphone, 74% of the patients had ever used at least two different types of opioids and 31% at least three different opioid types (Table 1).

The median oral MED was 600 mg/day (range 72–2,592 mg/day) before the start of hydromorphone (Table 1). Ninety-one patients were rotated to subcutaneous administration and 13 patients to intravenous administration of hydromorphone. The median oral dose of hydromorphone at start was 48 mg/day (range 5–216 mg).

Achievement of pain control

Adequate pain control (without intolerable side effects) was achieved in 86 out of 104 patients (83%) within a mean of 5.0 days [standard deviation (sd) = 3.4; Fig. 1]. There was no relationship between number of opioids patients used before rotating to hydromorphone and percentage of patients achieving adequate pain control on parenteral hydromorphone. Before this rotation, 54 patients (52%) had side effects [mostly somnolence (n = 22) or nausea (n = 18)]. Eight of the 86 patients had side effects at adequate pain control [mostly nausea (n = 3), constipation (n = 4)], although these patients and their physicians were satisfied with the management of the side effects and both were unwilling to change policy. The mean pain intensity at rest in these 86 patients significantly decreased from 5.4 (sd = 2.1) to 2.4 (sd = 1.5; n = 78; p < 0.001). The mean pain intensity with movement significantly decreased from 7.4 (sd = 1.6) to 3.8 (sd = 1.5; n = 53; p < 0.001).

Among the 61 patients who were rotated to hydromorphone mainly because of inadequate pain control with/without (expected) volume problems with parenteral administration, 52 (85%) reached adequate pain control. In addition, a subgroup analysis, comparing patients with and without expected delivery problems due to high opioid dosages, showed similar percentage of patients receiving adequate pain control (90% vs. 83%; p = 0.47). Among the 43 patients who were rotated to hydromorphone mainly because of opioid-related side effects, adequate pain control with tolerable side effects was reached in 34 (79%, Fig. 1). In both groups of successfully treated patients, mean pain intensity scores at rest and with movement decreased significantly with titration of hydromorphone (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pain intensity scores in patients successfully rotated to parenteral hydromorphone

| Total (n = 86) | Pain (n = 52) | Side effects (n = 34) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | |

| Daily dose hydromorphone (mg), median (range) | 48 (5–144) | 48 (5–144) | 48 (12–144) | 65 (10–144) | 24 (5–72) | 34 (5–96) |

| Pain at rest, mean (sd) | 5.4 (2.1) | 2.4 (1.5)* | 5.7 (2.2) | 2.6 (1.5)* | 4.8 (1.8) | 2.1 (1.4)* |

| Pain with movement, mean (sd) | 7.4 (1.6) | 3.8 (1.5)* | 7.5 (1.7) | 3.5 (1.6)* | 7.1 (1.6) | 4.2 (1.4)* |

*p < 0.001

T0 baseline, T1 at adequate pain control

Eighteen patients (17%) did not reach adequate pain control. Six patients died before reaching adequate pain control with parenteral hydromorphone (2–13 days); two of them were treated with palliative sedation in their terminal phase because of refractory pain and dyspnea. Twelve patients failed because of inadequate pain control and/or uncontrolled side effects. Ten of them were given spinal analgesia; one patient received a nerve block, and in one patient the intervention used was unknown.

Duration of effect on hydromorphone and overall survival

Among the 86 patients who achieved adequate pain control on parenteral hydromorphone, 74 patients (86%) did not undergo further invasive procedures, 49 patients (57%) died while still on parenteral hydromorphone, 17 patients (20%) were rotated to oral or transdermal opioids, and 8 patients (9%) were still using parenteral hydromorphone at the time of data collection. Eleven patients ultimately rotated to spinal analgesia and 1 patient received a nerve block (Fig. 1).

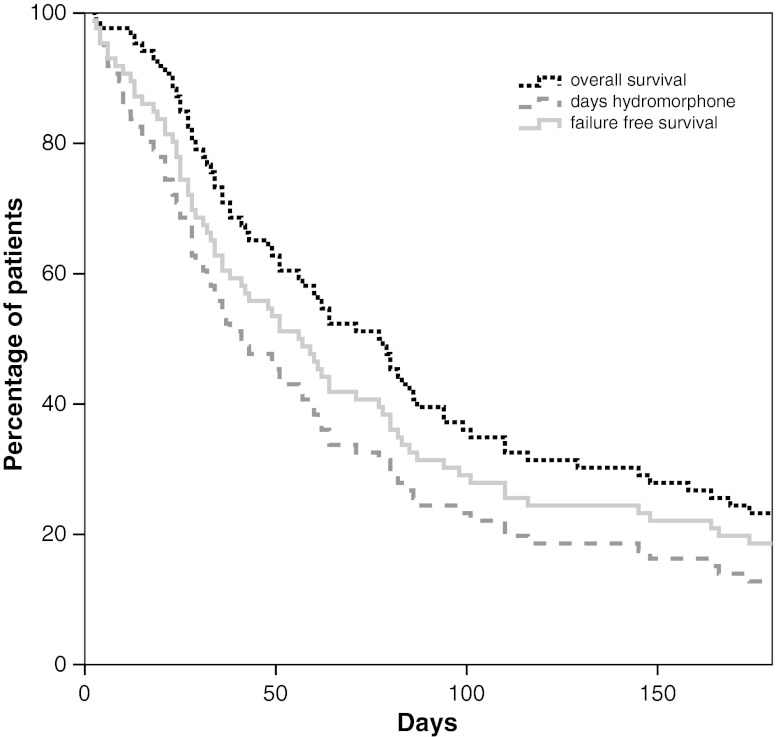

The median failure-free treatment period of the 86 responding patients was 57 days (range 2–1,094 days), whereas their median duration of survival was 78 days (range 3–1,094 days). At the end of follow-up, ten patients were still alive (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Failure-free treatment duration and overall survival in patients who reached adequate pain control on parenteral hydromorphone (n = 86). Overall survival was calculated from the start of hydromorphone until death or end of the study (black dotted line); duration of hydromorphone use (grey dashed line). Failure-free survival was defined as the period from the start of hydromorphone until death or the application of more invasive techniques (light grey line)

Other possible influencing factors

At baseline, 100 patients (96%) used adjuvant analgesics while rotated to parenteral hydromorphone (Table 3). Ninety one of them used two or more adjuvant analgesics at baseline. In the 86 patients who reached adequate pain control, adjuvant analgesics were changed in 41 of them (Table 3). For example, six patients already used S(+)-ketamine before starting parenteral hydromorphone, three of them stopped with S(+)-ketamine before their pain was adequately treated. Thirteen other patients started with S(+)-ketamine between the start of parenteral hydromorphone and the moment adequate pain control was achieved (Table 3). A subgroup analysis comparing patients with and without the use of S(+)-ketamine showed similar percentages of patients achieving adequate pain control (87% vs. 82%, p = 0.54). Although a longer period was needed to achieve adequate pain control in those patients who used S(+)-ketamine compared to those who did not (median of 7 vs. 3 days; p = 0.004), the median dosage of hydromorphone at start and at the moment of reaching adequate pain control was similar in both groups. Haloperidol was added in four patients to control their side effects. Dexamethasone was added in three patients while having radiotherapy (Table 3). Thirteen patients received radiotherapy within 2 weeks before starting parenteral hydromorphone or during therapy with hydromorphone (Table 1) and achieved adequate pain control within a median of 6 days.

Table 3.

Adjuvant (analgesic) medication

| All patients (n = 104) | All patients who reached adequate pain control (n = 86) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| At the start of hydromorphone treatment, n (%) | At the start of hydromorphone treatment, n (%) | At adequate pain control, n (%) | |

| Acetaminophen | 89 (86) | 74 (86) | 74 (86) |

| NSAIDs | 77 (74) | 65 (76) | 68 (79) |

| S(+)-ketamine | 9 (9) | 6 (7) | 16 (19) |

| Antidepressants | 19 (18) | 16 (19) | 11 (13) |

| Anticonvulsants | 48 (46) | 39 (45) | 15 (18) |

| Dexamethasone | 5 (5) | 5 (6) | 8 (9) |

| Haloperidol | 15 (14) | 10 (12) | 14 (16) |

| Methylphenidate | 3 (3) | 3 (4) | 4 (5) |

NSAIDs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Discussion

In the present study, we have shown that parenteral hydromorphone is highly effective in advanced cancer patients with serious cancer-related pain who were extensively pretreated with opioids. Eighty-three percent of the patients achieved adequate pain control with tolerable side effects within a mean of 5 days. Moreover, among 86% of these patients, the pain was adequately controlled until death without the need of further invasive procedures. The median failure-free treatment period of 57 days covered a substantial part of the median survival of 78 days in the responding patients. Thus, in advanced cancer patients with severe cancer-related pain despite the use of several lines of opioids, rotation to continuous parenteral administration of hydromorphone seems an elegant, highly effective option.

For patients who fail on a certain opioid, opioid rotation is regularly used, either as a change in the opioid drug or as a change in the route of administration. However, it is unknown whether opioid rotation is the choice to make in extensively pretreated cancer patients. In Table 4 all currently published prospective and retrospective studies on opioid rotation are described. In most studies the patient population was unclearly described. Moreover, only five studies gave some indication that advanced cancer patients were included in the study [19–23]. Unfortunately, these studies reported only over a short period of follow-up (7–28 days) and clear information on previous opioid use was lacking (Table 4). Finally, none of these studies reported a rotation to parenteral hydromorphone. Thus, with the current study, we are the first to show that an opioid switch to parenteral hydromorphone in a well-described, extensively pretreated advanced cancer patient population is a suitable and highly effective possibility.

Table 4.

Prospective and retrospective studies of opioid rotation in chronic cancer-related pain

| Reference | Number | Kind of rotation | Number of previous rotations | Mean follow-up (days) | MED mean (mg/day) | RR (%) | Effectiveness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain intensity | Side effects | |||||||

| Sawe et al. [27] | 14 | Various opioids (po/im) → Me (po) | N/A | 7 | N/A | 79 | N/A | N/A |

| Slover [28] | 5 | M, HM, or O (po/iv) → F (td) | N/A | 28 | 156 | 60 | Decreased | Constipation decreased, Drowsiness increased |

| Morley et al. [29] | 5 | M (po)→Me (po) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 80 | Decreased | N/A |

| Bruera et al. [30] | 37 | HM (sc) → Me (pr/po) | N/A | 40 | 4,140 | 84 | Decreased | N/A |

| Cherny et al. [31] | 80 | Various drugs and/or routes | 2 | N/A | N/A | 100 | Decreased | Decreased |

| Paix et al. [32] | 11 | M (po/sc/epi) → F (sc) | N/A | 32 | 245 | 73 | No difference | Decreased |

| De Stoutz et al. [33] | 80 | Various opioids → various opioids | N/A | N/A | 1,731a | 73 | Decreased | Decreased |

| De Conno et al. [34] | 196 | Various opioids → Me (po) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No difference | No difference |

| Maddocks et al. [21] | 13 | M (po/sc) → O (sc) | 0–1 | N/A | N/A | 69 | No difference | No difference |

| Hagen and Babul [35] | 44 | HM (po) ↔ O (po) | N/A | 149 | 229 | 70 | No difference | No difference |

| Ripamonti et al. [36] | 38 | M (po/sc/iv) → Me (or) | N/A | 3 | 145a | 100 | No difference | No difference |

| Ashby et al. [19] | 49 | Various opioids → various opioids, | N/A | 10 | 72a | 65 | Decreased | Decreased |

| Gagnon et al. [37] | 63 | M or HM (sc) → O (sc) | N/A | N/A | 342 | 51 | No difference | No difference |

| Mercadante et al. [38] | 24 | M (po) → Me (po) | N/A | 48 | 125 | 79 | Decreased | Decreased |

| Kloke et al. [39] | 103 | Various drugs → various drugs | 1.38 | N/A | N/A | 65 | N/A | N/A |

| Lee et al. [40] | 55 | Various opioids → HM (po) | 1.29 | N/A | 145.5 | 60 | Decreased | Decreased |

| Mercadante et al. [41] | 50 | M (po) → Me (po) | N/A | 4 | 180a | 80 | Decreased | Decreased |

| Santiago-Palma et al. [42] | 18 | F (iv) → Me (iv) | N/A | 4 | 1,159a | 89 | Decreased | Sedation decreased |

| Enting et al. [5] | 100 | Various opioids (po/td) → various opioids | N/A | 2 | 240a | 71 | Decreased | Decreased |

| McNamara [43] | 19 | M (po) → F (td) | N/A | 14 | 60–120 | 47 | No difference | Sleepiness decreased, drowsiness decreased |

| Moryl et al. [44] | 13 | Me (po/iv) → various opioids (iv) | 1–2 | 1 | 6,946b | 8 | Increased | Dysphoria increased |

| Tse et al. [22] | 37 | M (po) → Me (po) | N/A | 14 | 120a | 73 | Decreased | Decreased |

| Benitez-Rosario et al. [20] | 17 | F (td) → Me (po) | N/A | 7 | 360a | 80 | Decreased | Decreased |

| Mercadante et al. [45] | 31 | F (td) → Me (po) or vv | N/A | 3 | 360 | 81 | Decreased | Decreased |

| Morita et al. [46] | 20 | M (po) → F (td/iv/sc) | N/A | 7 | 64 | 90 | Decreased | Delirium score decreased |

| Muller-Busch et al. [23] | 161 | Various opioids → various opioids | N/A | 28 | 204 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Narabayashi et al. [47] | 25 | M (po) → O (po) | N/A | 2.3 | 44 | 84 | Decreased | Decreased |

Abbreviations: po per os, pr per rectal, td transdermal, sc subcutaneous, iv intravenous, im intramuscular, HM hydromorphone, M morphine, Me methadone, O oxycodone, F fentanyl, vv visa versa, N/A not available, RR response rate, definitions differ, MED oral morphine equivalent daily doses prerotation opioid

aMedian instead of mean

bA 13.5:1 conversion was used

In advanced cancer patients, subcutaneous administration of opioids is preferable to intravenous administration since it is more useful in the outpatient setting, has a lower risk of complications like infections, and is less expensive [12, 24]. Since hydromorphone can be administered in high concentrations in very low volumes subcutaneously, it has been found to be useful when high doses of opioids are needed [12]. In our center, the maximum volume given subcutaneously is 2 ml/h for morphine and hydromorphone and 4 ml/h for fentanyl. Morphine and hydromorphone are available in concentrations of 10 mg/ml, fentanyl in a concentration of 50 μg/ml. In a substantial part of our patients, it was not possible to titrate morphine or fentanyl subcutaneously anymore because of too large volumes needed. To circumvent this problem, higher concentrations of opioids per milliliter could be prepared. However, in our experience, this often leads to an unacceptable high percentage of annoying local skin infiltrations.

There are several limitations that should be considered in interpreting the results of our study. First, it is a retrospective study. However, even though the definitions of the outcome measures were made retrospectively, the patients were evaluated prospectively for pain intensity and side effects. Due to the retrospective design, we were not able to give a complete overview of the analgesics patients had used before they were treated in our hospital. It is thus likely that the analgesics presented in Table 1 are an underestimation of the previously used analgesics. Second, this study was a single-center study, which hampered the extrapolation of the results. Third, adequate pain control could be due to concomitant treatment with S(+)-ketamine or undergoing radiotherapy instead of an effect of hydromorphone alone. A pain-reducing effect of using S(+)-ketamine could not be excluded, although it seems not very likely. Besides the pain-reducing effect, S(+)-ketamine has been suggested to restore opioid sensitivity for its analgesic effects thereby diminishing the opioid doses needed to achieve adequate pain control. Due to the fact that the success rate in patients with and without S(+)-ketamine was the same in the subgroup analysis, the main effect we found in this study is most likely caused by hydromorphone. As far as radiotherapy is concerned, the effect of radiotherapy on pain relief can be expected after 2–4 weeks [25, 26]. Given the fact that patients with radiotherapy received adequate pain control within a median of 6 days, a pain-reducing effect of radiotherapy in these patients cannot be fully excluded.

In conclusion, in patients with advanced cancer and serious unstable cancer-related pain refractory to other opioids, parenteral continuous administration of hydromorphone seems effective and should be considered even after extensive pretreatment with opioids. In this vulnerable patient population, often in their last weeks to months of life, adequate pain management is of the utmost importance. However, until now, opioid rotation is used by trial and error. For individual patients, underlying factors related to beneficial and detrimental effects of specific opioids are unknown. For optimizing patient-tailored opioid therapy, insights in underlying pharmacodynamic mechanisms are eagerly awaited.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest. None of the authors has any financial disclosures.

Funding

This study is supported by department funding only.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(9):1437–1449. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Cancer pain relief and palliative care. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1990;804:1–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zech DF, Grond S, Lynch J, Hertel D, Lehmann KA. Validation of World Health Organization Guidelines for cancer pain relief: a 10-year prospective study. Pain. 1995;63(1):65–76. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00017-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fine PG, Portenoy RK, Ad Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence Review and Guidelines for Opioid Rotation Establishing “best practices” for opioid rotation: conclusions of an expert panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(3):418–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enting RH, Oldenmenger WH, van der Rijt CC, Wilms EB, Elfrink EJ, Elswijk I, Sillevis Smitt PA. A prospective study evaluating the response of patients with unrelieved cancer pain to parenteral opioids. Cancer. 2002;94(11):3049–3056. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enting RH, Oldenmenger WH, Van Gool AR, van der Rijt CC, Sillevis Smitt PA. The effects of analgesic prescription and patient adherence on pain in a Dutch outpatient cancer population. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(5):523–531. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar MG, Lin S. Hydromorphone in the management of cancer-related pain: an update on routes of administration and dosage forms. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2007;10(4):504–518. doi: 10.18433/j3vc75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanks GW, Conno F, Cherny N, Hanna M, Kalso E, McQuay HJ, Mercadante S, Meynadier J, Poulain P, Ripamonti C, Radbruch L, Casas JR, Sawe J, Twycross RG, Ventafridda V, Expert Working Group of the Research Network of the European Association for Palliative Care Morphine and alternative opioids in cancer pain: the EAPC recommendations. Br J Cancer. 2001;84(5):587–593. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mercadante S. Problems of long-term spinal opioid treatment in advanced cancer patients. Pain. 1999;79(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray A, Hagen NA. Hydromorphone. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29(5 Suppl):S57–S66. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quigley C, Wiffen P. A systematic review of hydromorphone in acute and chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(2):169–178. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00643-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruera E, MacEachern T, Macmillan K, Miller MJ, Hanson J. Local tolerance to subcutaneous infusions of high concentrations of hydromorphone: a prospective study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1993;8(4):201–204. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(93)90128-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy MH. Pharmacologic treatment of cancer pain. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(15):1124–1132. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610103351507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Portenoy RK, Lesage P. Management of cancer pain. Lancet. 1999;353(9165):1695–1700. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CBO, VIKC (2008) Diagnostiek en behandeling van pijn bij patiënten met kanker. Van Zuiden Communications B.V., Alphen a/d/Rijn

- 16.Turk DC, Okifuji A. Assessment of patients’ reporting of pain: an integrated perspective. Lancet. 1999;353(9166):1784–1788. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawlor P, Turner K, Hanson J, Bruera E. Dose ratio between morphine and hydromorphone in patients with cancer pain: a retrospective study. Pain. 1997;72(1–2):79–85. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruera E, Pereira J, Watanabe S, Belzile M, Kuehn N, Hanson J. Opioid rotation in patients with cancer pain. A retrospective comparison of dose ratios between methadone, hydromorphone, and morphine. Cancer. 1996;78(4):852–857. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960815)78:4<852::AID-CNCR23>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashby MA, Martin P, Jackson KA. Opioid substitution to reduce adverse effects in cancer pain management. Med J Aust. 1999;170(2):68–71. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1999.tb126885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benitez-Rosario MA, Feria M, Salinas-Martin A, Martinez-Castillo LP, Martin-Ortega JJ. Opioid switching from transdermal fentanyl to oral methadone in patients with cancer pain. Cancer. 2004;101(12):2866–2873. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maddocks I, Somogyi A, Abbott F, Hayball P, Parker D. Attenuation of morphine-induced delirium in palliative care by substitution with infusion of oxycodone. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1996;12(3):182–189. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(96)00050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tse DM, Sham MM, Ng DK, Ma HM. An ad libitum schedule for conversion of morphine to methadone in advanced cancer patients: an open uncontrolled prospective study in a Chinese population. Palliat Med. 2003;17(2):206–211. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm696oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muller-Busch HC, Lindena G, Tietze K, Woskanjan S. Opioid switch in palliative care, opioid choice by clinical need and opioid availability. Eur J Pain. 2005;9(5):571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanks GW, Conno F, Cherny N, Hanna M, Kalso E, McQuay HJ, Mercadante S, Meynadier J, Poulain P, Ripamonti C, Radbruch L, Casas JR, Sawe J, Twycross RG, Ventafridda V. Morphine and alternative opioids in cancer pain: the EAPC recommendations. Br J Cancer. 2001;84(5):587–593. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong D, Gillick L, Hendrickson FR. The palliation of symptomatic osseous metastases: final results of the Study by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Cancer. 1982;50(5):893–899. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820901)50:5<893::AID-CNCR2820500515>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Linden YM, Steenland E, van Houwelingen HC, Post WJ, Oei B, Marijnen CA, Leer JW, Dutch Bone Metastasis Study Group Patients with a favourable prognosis are equally palliated with single and multiple fraction radiotherapy: results on survival in the Dutch Bone Metastasis Study. Radiother Oncol. 2006;78(3):245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sawe J, Hansen J, Ginman C, Hartvig P, Jakobsson PA, Nilsson MI, Rane A, Anggard E. Patient-controlled dose regimen of methadone for chronic cancer pain. Br Med J Clin Res Ed. 1981;282(6266):771–773. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6266.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slover R. Transdermal fentanyl: clinical trial at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1992;7(3 Suppl):S45–S47. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(92)90053-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morley JS, Watt JW, Wells JC, Miles JB, Finnegan MJ, Leng G. Methadone in pain uncontrolled by morphine. Lancet. 1993;342(8881):1243. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92228-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruera E, Watanabe S, Fainsinger RL, Spachynski K, Suarez-Almazor M, Inturrisi C. Custom-made capsules and suppositories of methadone for patients on high-dose opioids for cancer pain. Pain. 1995;62(2):141–146. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00257-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cherny NJ, Chang V, Frager G, Ingham JM, Tiseo PJ, Popp B, Portenoy RK, Foley KM. Opioid pharmacotherapy in the management of cancer pain: a survey of strategies used by pain physicians for the selection of analgesic drugs and routes of administration. Cancer. 1995;76(7):1283–1293. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951001)76:7<1283::AID-CNCR2820760728>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paix A, Coleman A, Lees J, Grigson J, Brooksbank M, Thorne D, Ashby M. Subcutaneous fentanyl and sufentanil infusion substitution for morphine intolerance in cancer pain management. Pain. 1995;63(2):263–269. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Stoutz ND, Bruera E, Suarez-Almazor M. Opioid rotation for toxicity reduction in terminal cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10(5):378–384. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(95)90924-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Conno F, Groff L, Brunelli C, Zecca E, Ventafridda V, Ripamonti C. Clinical experience with oral methadone administration in the treatment of pain in 196 advanced cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(10):2836–2842. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.10.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hagen NA, Babul N. Comparative clinical efficacy and safety of a novel controlled-release oxycodone formulation and controlled-release hydromorphone in the treatment of cancer pain. Cancer. 1997;79(7):1428–1437. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19970401)79:7<1428::AID-CNCR21>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ripamonti C, Groff L, Brunelli C, Polastri D, Stavrakis A, De Conno F. Switching from morphine to oral methadone in treating cancer pain: what is the equianalgesic dose ratio? J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(10):3216–3221. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.10.3216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gagnon B, Bielech M, Watanabe S, Walker P, Hanson J, Bruera E. The use of intermittent subcutaneous injections of oxycodone for opioid rotation in patients with cancer pain. Supp Care Cancer. 1999;7(4):265–270. doi: 10.1007/s005200050259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mercadante S, Casuccio A, Calderone L. Rapid switching from morphine to methadone in cancer patients with poor response to morphine. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(10):3307–3312. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.10.3307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kloke M, Rapp M, Bosse B, Kloke O. Toxicity and/or insufficient analgesia by opioid therapy: risk factors and the impact of changing the opioid. A retrospective analysis of 273 patients observed at a single center. Supp Care Cancer. 2000;8(6):479–486. doi: 10.1007/s005200000153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee MA, Leng ME, Tiernan EJ. Retrospective study of the use of hydromorphone in palliative care patients with normal and abnormal urea and creatinine. Palliat Med. 2001;15(1):26–34. doi: 10.1191/026921601669626431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mercadante S, Casuccio A, Fulfaro F, Groff L, Boffi R, Villari P, Gebbia V, Ripamonti C. Switching from morphine to methadone to improve analgesia and tolerability in cancer patients: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(11):2898–2904. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.11.2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santiago-Palma J, Khojainova N, Kornick C, Fischberg DJ, Primavera LH, Payne R, Manfredi P. Intravenous methadone in the management of chronic cancer pain: safe and effective starting doses when substituting methadone for fentanyl. Cancer. 2001;92(7):1919–1925. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011001)92:7<1919::AID-CNCR1710>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McNamara P. Opioid switching from morphine to transdermal fentanyl for toxicity reduction in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2002;16(5):425–434. doi: 10.1191/0269216302pm536oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moryl N, Santiago-Palma J, Kornick C, Derby S, Fischberg D, Payne R, Manfredi PL. Pitfalls of opioid rotation: substituting another opioid for methadone in patients with cancer pain. Pain. 2002;96(3):325–328. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00465-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mercadante S, Ferrera P, Villari P, Casuccio A. Rapid switching between transdermal fentanyl and methadone in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5229–5234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.13.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morita T, Takigawa C, Onishi H, Tajima T, Tani K, Matsubara T, Miyoshi I, Ikenaga M, Akechi T, Uchitomi Y, Japan Pain RPMaP-OSG Opioid rotation from morphine to fentanyl in delirious cancer patients: an open-label trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30(1):96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Narabayashi M, Saijo Y, Takenoshita S, Chida M, Shimoyama N, Miura T, Tani K, Nishimura K, Onozawa Y, Hosokawa T, Kamoto T, Tsushima T, Advisory Committee for Oxycodone Study Opioid rotation from oral morphine to oral oxycodone in cancer patients with intolerable adverse effects: an open-label trial. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38(4):296–304. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]