The striking advances made in recent years in understanding the mechanisms that regulate transcription of viral genes by the cellular RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) have greatly intensified efforts to develop new antiviral compounds that disrupt this key step and therefore can be used to fight human disease. Many viruses have developed unique strategies to target the host cell transcription machinery to the viral genome and to enhance RNAPII transcription in a manner and timing that is critical to the execution of the virus life cycle in infected cells. Virus-encoded transcription factors that interface directly with the host cell transcription machinery are especially attractive targets for developing drugs that can disrupt viral gene expression without affecting the normal process of transcriptional control at cellular genes.

Inhibitors of HIV-1 provide an important paradigm for this approach because of the urgent need for new therapies that either can complement existing treatment regimens or can be used to combat drug-resistant viral variants that arise during the course of available treatments. In the current issue of the Proceedings, a highly innovative approach is proposed by Dickinson et al. (1) to block HIV-1 replication through disrupting the ability of host cell proteins to bind to the viral enhancer. The experimental design involves targeting synthetic ligands to preselected regulatory DNA sequences in the HIV-1 enhancer. These compounds mimic the DNA recognition properties of regulatory proteins and form stable and specific complexes with duplex DNA, generating specific “footprints” in DNase I protection assays. By directing such compounds to sequences that immediately flank or partially overlap the DNA-recognition element rather than to the core recognition motif itself, the investigators reasoned that the ligands will act selectively on the HIV-1 enhancer without affecting the transcription of cellular genes.

The specific DNA-binding ligands used by Dickinson et al. (1) are 9- and 11-residue hairpin polyamides that contain N-methylimidazole (Im) and N-methylpyrrole (Py) amino acids, which have been shown to bind to minor groove sequences of DNA with affinities and specificities that are comparable or better than those of many cellular enhancer-binding proteins (for review, see ref. 2). A series of elegant studies from the laboratory of P. B. Dervan have demonstrated that the DNA-binding specificity of these compounds arises from the cross-pairing of Py and Im amino acids within the polyamide (3–6). Thus, G-C base pairs in DNA are targeted by Im/Py pairs in the polyamide, C-G pairs are targeted by Py/Im pairs, and A-T or T-A sequences are targeted by Py/Py pairs. In this manner, it is possible to synthesize ligands that, in principle, will bind to any preselected 6- or 7-bp DNA recognition site. Recent studies have shown that such ligands can block the DNA-binding and transcriptional activities of gene-specific transcription factors in vitro and in vivo (7, 8). Unlike oligodeoxyribonucleotides, which also can form triple helices with specific DNA sequences and can disrupt DNA-bound factors, polyamides have been shown to be readily permeable to cells, and, consequently, the effects of these synthetic ligands on gene expression and virus replication can be assessed directly in cultured cells.

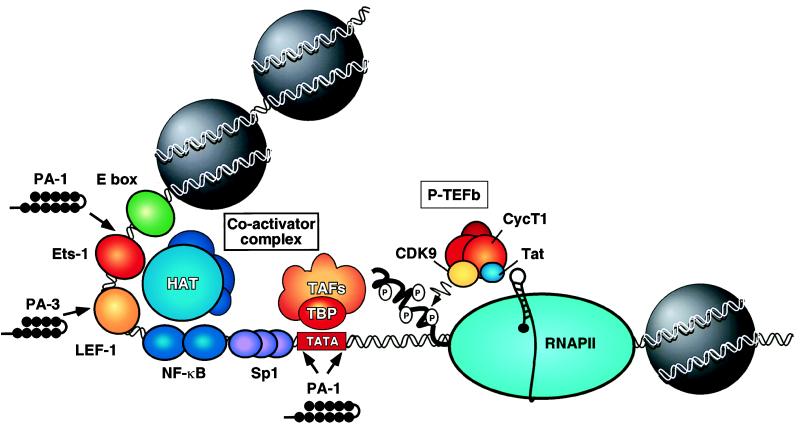

The target in the current study is the HIV-1 transcription unit, which contains a TATA box motif, Sp1 binding sites in the promoter, and an upstream enhancer region recognized by NF-κB, LEF-1, Ets-1, and proteins that bind the Ebox motif, such as USF and TFE-3 (Fig. 1; for review of the HIV-1 enhancer, see ref. 9). These factors are critical for initiation of viral transcription; however, transcription complexes formed at the HIV-1 promoter are blocked strongly at an early step in elongation by a “pause” hairpin that forms at the very 5′ end of the viral RNA (10), as well as by negative elongation factors present in the RNAPII initiation complex (11–13). To overcome this block to elongation, HIV-1 encodes a regulatory protein, Tat, which enters the nucleus and functions as an HIV-1 promoter-specific transcription factor. Tat interacts with a positive transcription elongation factor complex (P-TEFb; refs. 11, 14, and 15), which contains the cdc2-related kinase CDK9, the cyclin T1 protein, and other, as yet unidentified subunits. Binding of Tat to the CycT1 subunit tethers the P-TEFb complex to the nascent TAR RNA element (16) in a step that enhances phosphorylation of the RNAPII carboxyl-terminal domain (CTD) and effectively overcomes the block to elongation (14–17; for review, see refs. 18–20). Of interest, levels of cyclin T1 protein and CDK9/P-TEFb kinase activity are induced strongly in cytokine-activated lymphoid cells (15, 21), concomitant with greatly increased levels of nuclear NF-κB. As a result, Tat acts in a synergistic manner with the HIV-1 enhancer-binding proteins to induce viral transcription strongly in activated T cells and macrophages.

Figure 1.

View of the integrated HIV-1 proviral transcription control region. Shown are the recognition sites for the HIV-1 enhancer-binding factors. The enhancer promotes initiation of RNAPII transcription through the recruitment of a coactivator complex(es) that contains associated histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activities. Transcription initiation also requires the binding of Sp1 to the promoter, as well as the TATA-binding protein, TBP, and associated factors (TAFs). The HIV-1-encoded transcription factor Tat interacts with the cyclin T1 subunit of P-TEFb to direct the P-TEFb complex to nascent TAR RNA and enhance elongation of RNAPII transcription. The binding sites for polyamides used by Dickinson et al. (1) to target HIV-1 promoter and enhancer sequences are shown: Polyamide 1 (PA-1) blocks binding of TBP and ETS-1 whereas Polyamide 3 (PA-3) blocks the binding of the lymphoid enhancer-binding factor LEF-1.

To attack the HIV-1 enhancer, Dickinson et al. (1) targeted two different minor-groove DNA-binding proteins: TBP, which recognizes the TATA box in the HIV-1 promoter, and LEF-1 (22), a lymphoid cell-enriched enhancer-binding factor related to the high mobility group (HMG-1) protein family, which binds to the enhancer. These factors were disrupted by using two different polyamides: PA-1, which binds to sequences flanking the HIV-1 TATA box as well as a sequence that overlaps the Ets-1 binding site in the enhancer, and PA-3, which binds to sequences overlapping the LEF-1 site. PA-1 and PA-3 were shown to compete for binding of these transcription factors to the HIV-1 promoter and inhibit HIV-1 transcription in vitro. When tested for their ability to affect HIV-1 replication in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), the individual polyamides reduced virus replication modestly, as measured by the release of the viral capsid antigen p24. In combination, however, the two polyamides inhibited virus replication dramatically. Thus, replication of the T cell tropic virus isolate WEAU 1.6 dropped to levels below detection after 6–8 days of incubation with PA-1 and PA-3. The polyamides also significantly disrupted replication of a macrophage-tropic virus isolate (SF 162). The polyamides were maximally effective at 1 μM and were as effective as azidothymidine (AZT) under parallel conditions, with much less evidence of gross cellular toxicity in cell viability assays. The inhibition of virus replication did not appear to be an indirect effect of the polyamides on activation of host cell proteins because PA-1 and PA-3 in combination did not affect the expression of a number of cellular genes involved in T cell activation nor did they influence transcription of the T cell surface receptors CD4 or CD8. The polyamides appeared to block HIV-1 replication selectively because control polyamides failed to interfere with virus replication under conditions in which PA-1 and PA-3 reduced virus replication by a factor of 10. Taken together, these results provide very intriguing evidence that polyamides can be useful inhibitors of HIV-1.

Although these initial results are very promising, how selective are the polyamide inhibitors, and how certain are we of the mechanism of virus inhibition? Because the polyamides recognize relatively short stretches of DNA (6–7 bp), they will bind at many sites throughout the viral genome. Although PA-1 and PA-3 were shown to block HIV-1 transcription in vitro, no experiments were presented that demonstrate inhibition of HIV-1 transcription in vivo, either in transient expression assays or in the virus replication studies. One could imagine that the polyamides will interfere with the binding of other proteins, such as HMG-1, to the HIV-1 genome and may disrupt other steps in the virus life cycle, such as nuclear import of the viral preintegration complex or virus integration into the host cell genome. It is not clear that inhibition occurs through the targeted DNA site, although future studies of mutant viruses could be used to establish that the HIV-1 enhancer and TATA box are required for inhibition by PA-1 and PA-3.

The HIV-1 TATA box and upstream Ets-1 binding element are, in principle, excellent targets for inhibition by polyamides because these sequences are highly conserved among virus isolates and are important for virus replication. By contrast, the LEF-1 recognition element is not an ideal target because the LEF-1 binding site is present in only ≈30% of the HIV-1 isolates that have been sequenced to date and because LEF-1 is not expressed in macrophages. Indeed, if PA-3 acts only to block binding of LEF-1, it should be ineffective in macrophages. Another limitation of the strategy proposed here is that it relies on the conservation of the factor binding sites as well as the sequences that surround these sites because these are the motifs to which the polyamide is targeted. However, these sequences will not be conserved necessarily among different viruses, and, in particular, there is no selective pressure for HIV-1 to maintain nonessential sequences in the vicinity of any given transcription factor binding site. For example, inspection of the sequence for various viral isolates reveals that some lack the binding site for PA-1, PA-3, or both. Therefore, specific polyamides might affect only certain virus isolates, or they may act in a cell-specific manner, depending on the expression pattern of the transcription factor. Given the short recognition site (6–7 bp) of these hairpin polyamides, it is likely that they will bind and disrupt the expression of some cellular genes. Indeed, PA-3 was shown to block binding of the TFIIIA protein to the 5S RNA gene and to inhibit transcription of the 5S gene in vivo (7, 8) at levels 10× below those used to inhibit HIV-1 replication.

Perhaps the most significant problem with the strategy proposed here is the ease with which HIV-1 can mutate and evolve to evade chemical inhibitors, as well as the existing genetic evidence indicating that no single transcription control element is absolutely essential for virus replication. Compounding this problem further is the need to target the polyamides to nonessential DNA sequences. As a result, HIV-1 may escape readily from polyamide inhibitors simply by mutating the targeted binding site. Although in principle this problem could be countered with additional polyamides directed against the newly evolved virus sequences, this possibility seems implausible given that infected individuals may have multiple viruses with different enhancer sequences at any given time.

In summary, the approach adopted by Dickinson et al. (1) does not address fully the problems intrinsic to inhibiting a complex virus such as HIV-1. Nevertheless, the observation that simple cell-permeable compounds such as polyamides can significantly reduce virus replication in vivo with low apparent toxicity to the cell represents a very encouraging step forward. The development of polyamides with high affinity and specificity and broad target site recognition is a remarkable achievement that greatly advances our ability to manipulate the binding of proteins to DNA. These site-specific inhibitors should be applicable to a diverse spectrum of problems in current biological research. With respect to viruses, polyamides could be especially useful as specific inhibitors of virus-encoded DNA-binding transcription factors. For example, the HTLV-I-encoded transcriptional activator Tax forms a complex with the cellular transcription factor CREB and extends its binding to include unique sequences in the minor groove of the DNA that flank the CREB binding site (23, 24). Consequently, a polyamide directed to this location might disrupt the binding of the Tax–CREB complex to the HTLV-I promoter, without affecting normal CREB activity in the cell. Undoubtedly, there also will be many important applications for site-specific polyamides in processes other than transcription (e.g., DNA replication, recombination, and repair) that are mediated by specific DNA-binding proteins.

In the future, it is likely that new generations of polyamides will be developed that recognize larger sequences of DNA with enhanced DNA-binding specificity, which may enhance the efficacy of these drugs and help circumvent any undesired effects on cellular gene activity. Dervan and colleagues recently have extended this technology by designing polyamides that recognize sequences as long as 16 bp (25) and can be targeted to the major groove of DNA (26), which should expand greatly the range of proteins that can be selected for disruption. The extent to which the virus can escape from targeted inhibition by the acquisition of mutations in the polyamide binding sites, and the potential toxicity of polyamides in the body, remain important unresolved questions. As the mechanisms of HIV-1 enhancer activation and Tat transactivation are elaborated further, it is likely that new approaches will be suggested to selectively disrupt HIV-1 transcription in infected cells. Compounds that block the kinase activity of CDK9/P-TEFb already have been shown to be highly effective inhibitors of Tat (11), and drugs that prevent the binding of Tat to cyclin T1 could be even more specific. Combinations of drugs that block Tat and the HIV-1 enhancer would be expected to act in a highly synergistic manner to down-regulate viral transcription in infected cells. Thus, as the transcriptional control mechanisms that regulate HIV-1 gene expression continue to be defined in increasing detail, there is every reason to expect that transcriptional inhibitors will be developed as selective and effective therapeutics for HIV-1.

Footnotes

A commentary on this article begins on page 12890.

References

- 1. Dickinson L A, Gulizia R J, Trauger J W, Baird E E, Mosier D E, Gottesfeld J M, Dervan P B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12890–12895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.12890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wemmer D E, Dervan P B. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:355–361. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White S, Baird E E, Dervan P B. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12532–12537. doi: 10.1021/bi960744i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White S, Baird E E, Dervan P B. Chem Biol. 1997;4:569–578. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geierstanger B H, Mrksich M, Dervan P B, Wemmer D E. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:321–324. doi: 10.1038/nsb0496-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geierstanger B H, Mrksich M, Dervan P B, Wemmer D E. Science. 1994;266:646–650. doi: 10.1126/science.7939719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neely L, Trauger J W, Baird E E, Dervan P B, Gottesfeld J M. J Mol Biol. 1997;274:439–445. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottesfeld J M, Neely L, Trauger J W, Baird E E, Dervan P B. Nature (London) 1997;387:202–205. doi: 10.1038/387202a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones K A, Peterlin B M. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:717–743. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.003441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palangat M, Meier T I, Keene R G, Landick R. Mol Cell. 1998;1:1033–1042. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mancebo H, Lee G, Flygare J, Tomassini J, Luu P, Zhu Y, Peng J, Blau C, Hazuda D, Price D, et al. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2633–2644. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wada T, Takagi T, Yamaguchi Y, Ferdous A, Imai T, Hirose S, Sugimoto S, Yano K, Hartzog G A, Winston F, et al. Genes Dev. 1998;12:343–356. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.3.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu-Baer F, Lane W S, Gaynor R B. J Mol Biol. 1998;277:179–197. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu Y, Pe’ery T, Peng J, Ramanathan Y, Marshall N, Amendt B, Mathews M B, Price D H. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2622–2632. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang X, Gold M, Tang D, Lewis D, Aguilar-Cordova E, Rice A P, Herrmann C H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12331–12336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei P, Garber M, Fang S M, Fischer W H, Jones K A. Cell. 1998;92:451–462. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80939-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parada C A, Roeder R G. Nature (London) 1996;384:375–378. doi: 10.1038/384375a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones K A. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2593–2599. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cullen B R. Cell. 1998;93:685–692. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81431-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emerman M, Malim M H. Science. 1998;280:1880–1884. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrmann, C. H., Carroll, R. G., Wei, P., Jones, K. A. & Rice, A. P. (1998) J. Virol., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Carey M. Cell. 1998;92:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80893-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenzmeier B A, Giebler H A, Nyborg J K. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:721–731. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lundblad J R, Kwok R P, Laurance M E, Huang M S, Richards J P, Brennan R G, Goodman R H. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19251–19259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.19251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trauger J W, Baird E E, Deruan P B. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:3534–3535. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bremer R E, Baird E E, Dervan P B. Chem Biol. 1998;5:119–133. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]