Abstract

Research has yet to examine the relationship between financial well-being and community reintegration of veterans. To address this, we analyzed data from n=1,388 Iraq and Afghanistan War Era Veterans who completed a national survey on post-deployment adjustment. The results indicated that probable major depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and traumatic brain injury were associated with financial difficulties. However, regardless of diagnosis, veterans who reported having money to cover basic needs were significantly less likely to have post-deployment adjustment problems such as criminal arrest, homelessness, substance abuse, suicidal behavior, and aggression. Statistical analyses also indicated that poor money management (e.g. incurring significant debt or writing bad checks) was related to maladjustment, even among veterans at higher income levels. Given these findings, efforts aimed at enhancing financial literacy and promoting meaningful employment may have promise to enhance outcomes and improve quality of life among returning veterans.

Keywords: Veterans, Financial Well-Being, Post-Deployment Adjustment, Homelessness

A vital challenge faced by Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans returning home from combat is achieving financial well-being. This goal— which encompasses a sense of material security, the ability to make ends meet, opportunities to grow financially through work, and possessing knowledge and judgment to make good money management decisions1–3 —is not accomplished by all veterans post-deployment, and some struggle to afford basic needs. Veterans are not immune to economic downturns faced by civilians, and multiple deployments have been shown to disrupt family life4,5 which can reduce financial well-being and thereby increase financial strain. Other financial problems that have been identified among Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans include: predatory lending practices, with scammers often located near military bases; mismanagement of, or lack of experience with, finances by younger service members; and lack of an emergency savings plan.6

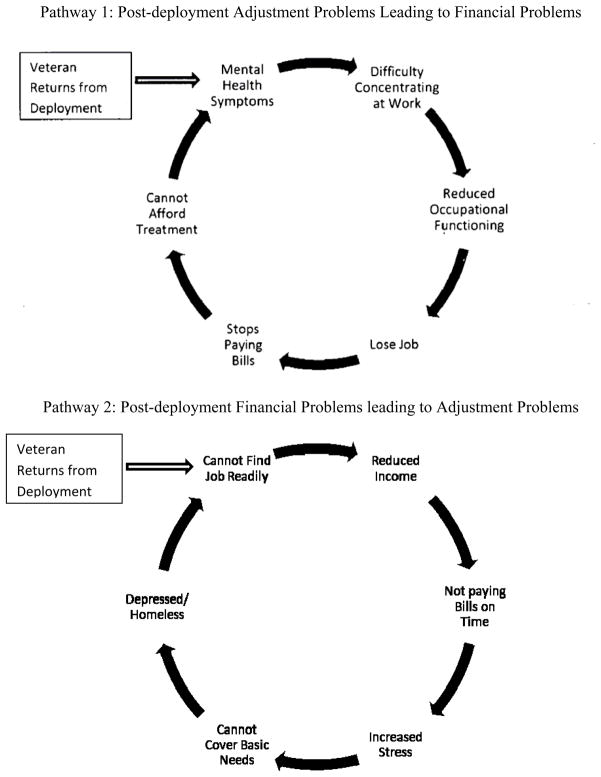

Financial strain could link to post-deployment problems in different ways (see Figure 1). One could postulate that posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), traumatic brain injury (TBI), or major depressive disorder (MDD) related to war experience7,8 might lead to disability entailing financial problems such as less income, unemployment, and debt. Substance abuse, which often co-occurs with these disorders, may further exacerbate money management difficulties experienced by veterans.9–11 Conversely, returning from deployments requires possible retraining for civilian work, making it more difficulty to find employment. If this is the case, then such veterans may be at risk of having lower income and more difficulty paying bills. Indeed, veterans comprise up to 41% of the homeless population12–15 and studies of homeless veterans have revealed an increased risk of criminal arrest and difficulty accessing vocational resources.12,13,16

FIGURE 1.

Hypothesized Associations between Post-Deployment Financial and Adjustment Problems

Despite the role that money likely plays in veteran community readjustment and attention in the popular press to veteran employment and adjustment issues,17 to our knowledge there has been little research examining the impact of veterans’ financial status or financial literacy on post-deployment adjustment. There are a number of questions where data could inform policies and interventions to alleviate post-deployment adjustment problems. Do psychological injuries such as PTSD, MDD, or TBI relate to financial characteristics of veterans? Does a veteran having money to cover basic needs (e.g., shelter, food, clothes) relate to fewer post-deployment adjustment problems, such as homelessness, suicidal ideation, criminal arrest, or even aggression? How does poor money management, as opposed to lower income alone, link to worse outcomes for veterans? What are some possible pathways between financial strain and post-deployment problems? The current study thus examines these questions through analysis of a national sample of Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans representing members of all military branches and reserves who have served since September 11, 2001.

Methods

Study Population

The National Post-Deployment Adjustment Survey (NPDAS) is part of a larger study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health to develop tools to screen for adjustment problems among veterans. For the NPDAS, the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) Environmental Epidemiological Service in May 2009 randomly selected a sample of N=3000 from all separated veterans and reservists who served in the U.S. military after September 11, 2001. The sample was stratified by gender, and women veterans were oversampled to ensure a large enough statistical power to analyze data for women veterans. In total, n=1,388 completed the survey, which yielded a 56% corrected-response rate (n=63 had incomplete addresses or were deceased and n=438 had incorrect addresses). Our response rate was comparable or exceeded recent national surveys of Iraq and Afghanistan military service members.18–20

Close examination found no significant bias in the final sample. Gender ratios did not differ significantly between responders and nonresponders. States with the largest military populations (CA, TX, FL, GA, NC, VA, PA) were similarly represented in response groups, and respondent demographics corresponded to known military demographics. The average age was 36 years for responders and 34 years for non-responders. Responder military branch (52% Army, 18% Air Force, 16% Navy, 13% Marines, and 1% Coast Guard) approximated the actual composition of the U.S. Armed Forces.21 Race/ethnicity ratios mirrored the current military breakdown (70% Caucasian and 30% African-American, Hispanic, or other). The final sample represented 50 states, Washington D.C., and 4 territories.

Procedure

After obtaining approval from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and Durham VA Medical Center Institutional Review Boards, the current survey used the Dillman Method22 to optimize response rate by making multiple and varied contacts with respondents and using mailings containing elements that connect personally with recipients. The online and print surveys were identical; 80% of respondents completed the survey online and 20% completed the print version. Prior to the primary survey, a pilot study of 500 surveys was used to identify unanticipated technical problems. Pilot study respondents received $40 for completing the survey and those who completed the survey during the remainder of the study period were reimbursed $50. Overall, 15% of the total sample took the survey during in the pilot phase and 85% completed the survey during in the main study. Apart from a $10 difference in participant payment, procedures were identical for both phases of the survey.

To analyze for differences in survey medium or reimbursement rate, the sample was compared on demographic and clinical variables. No significant differences between survey media or reimbursement rates were detected with Bonferroni adjustment, which is used when making multiple comparisons. Pooled data generated the final sample of N=1,388 Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans.

Measures

Financial Well-Being

Veterans were asked about their employment, annual income, and unsecured debt (excluding mortgages and car loans). The Quality of Life Index was used to inquire about perceived material security23 (coded as 0 if not satisfied with financial situation and coded as 1 if satisfied). The Quality of Life Interview24 was used to measure veterans’ ability to make ends meet and cover basic needs (food, shelter, clothes, transportation, social activities, and medical care). If the participant indicated having money to cover all these needs in the past year, this was coded as ‘1’; otherwise, the veteran was seen as being unable to meet basic needs, coded as ‘0’. Items from the Financial Capacity Instrument25 were used to assess whether in the past year participants: wrote bad checks, fell victim to a money scam, had their lights or power shut off, or were referred to a collection agency. Endorsement of ‘yes’ to any of these items, or report of an unsecured debt of greater than $40,000, was operationalized as “poor” money management; if participants said no to all these items and did not report unsecured debt greater than $40,000, this was operationalized as “good” money management.

Post-Deployment Adjustment Problems

Veterans were asked if they had been arrested, engaged in suicidal behavior, or had suicidal thoughts since returning home from service. Homelessness within the past year was also assessed. The Drug Misuse Screening Test (DAST)26 was used to measure drug misuse (cutoff score = 2), and the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT)27 was used to measure alcohol misuse (cutoff score = 7). Severe violence in the past year was measured by endorsement of items on the Conflict Tactics Scale28 or the MacArthur Community Violence Scale.29 indicating having caused serious harm to others or used a lethal weapon. Items on these scales indicating less severe acts were used to measure other physical aggression in the past year (i.e., kicking, slapping, and getting into fights).

Demographic, Military, and Clinical Covariates

Data were gathered regarding participant age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, income, education, military branch, time since last deployment, and combat exposure. PTSD was measured with the Davidson Trauma Scale;30 a cutoff score of 48 on this measure has shown .82 sensitivity, .94 specificity, and .87 diagnostic efficiency for probable PTSD.31 Using expert consensus guidelines,32 probable TBI was scored positive if head injury during military service was reported with at least one of the following: loss of consciousness, getting “knocked out,” being dazed or “seeing stars,” inability to recall the event immediately post-injury or upon regaining consciousness, experiencing a lapse of more than one hour post-injury before being able to remember new information, or brain surgery. The Patient Health Questionnaire was administered to assess depressive symptoms33, scores above 10 have sensitivity and specificity of .88 for probable MDD.34

Results

Analyses were weighted by gender because women were oversampled to 33% of the current sample but represented an estimated 15.6% of the military at the time of the survey according to Defense Manpower Data Center.21 As such, data were weighted to reflect the latter proportion, adjusting the sampled n=1,388 to a weight-adjusted n=1,102.

19% of participants reported at least a general equivalency or high school diploma, 35% reported some college coursework, and the remaining 46% had a college degree at the associates, bachelors, or graduate level. 48% of respondents served in the reserves or national guard, 80% were enlisted personnel (ranked between E1 and E7), and 15% were commissioned officers (ranked between O1 and O7). 16% indicated that they had served since September 11, 2001 but had not been deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan, 28% had multiple deployments to Iraq or Afghanistan, and 27% reported a deployment longer than one year. The average length of deployment was 10 months and the average time since last deployment was 4.5 years.

Of the psychological and cognitive disorders assessed, 20% of participants screened positive for PTSD, 17% met the criteria for probable TBI, and 24% endorsed symptoms meeting criteria probable MDD. 27% of the sample met the criteria for alcohol misuse, 7% met the criteria for drug misuse, 9% reported a criminal arrest since returning home, and 4% were homeless for a least one day during the previous year. 33% endorsed committing mostly minor aggressive behavior in the past year, with 11% meeting criteria for severe violence. In addition, 17% endorsed suicidal ideation and 5% reported self-harming behavior since returning home.

The median annual income of respondents was approximately $50,000 and 78% reported some employment in the last year. 72% of participants were satisfied with their financial situation, and 58% indicated that they were always able to afford food, clothes, transportation, housing, medical costs, and social activities. However, 43% indicated that treatment costs were a barrier to obtaining psychiatric care. During the previous year, 13% of participants lost a job, 15% wrote bad checks, 21% had been referred to collection agencies, 4% had been victims of money scams, and 5% had utilities or power shut off. 10% of respondents reported an unsecured debt greater than $40,000.

Chi-square analyses were used to test for significant differences and associations between two variables, as opposed to associations occurring by chance. When cell sizes of these comparisons were in the single digits, we employed Fisher’s Exact, which is a powerful statistical procedure that permits testing for significant differences even when there are few participants meeting a criterion.35 This is highlighted in tables when used.

As shown in Table 1, veterans with probable MDD, PTSD, or TBI were substantially less likely to have money to cover expenses for clothing and social activities than other veterans and more than twice as likely to have been referred to a collection agency. Correspondingly, participants screening positive for these conditions had lower income and were significantly less satisfied with their financial status. Interestingly, this subset of veterans also was less likely to be employed; conversely, they were more likely to be receiving VA disability benefits.

Table 2 illustrates veterans who were able to meet their basic needs were less likely to be homeless, be arrested, misuse alcohol, misuse drugs, endorse suicidal ideation/behavior, or report acts of physical aggression.

TABLE 2.

Financial Ability to Meet Basic Needs and Post-Deployment Adjustment Problems in Iraq/Afghanistan War Veterans

| Probable MDD, PTSD, or TBI (n=387) | No MDD, PTSD, or TBI (n= 715) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Does not meet Basic Needs (n=225) | Meets Basic Needs (n=148) | Chi-Sqr | P-value | Does not meet Basic Needs (n=210) | Meets Basic Needs (n=472) | Chi-Sqr | P-value | |

| Homeless Since Deployment * | 12% (n=36) | 3% (n=6) | 11.437 | 0.0007 | 5% (n=15) | 0.2% (n=1) | 29.2159 | <.0001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Arrested Since Deployment | 21% (n=49) | 6% (n=8) | 17.2286 | <.0001 | 8% (n=17) | 5% (n=23) | 2.7638 | 0.0801 |

|

| ||||||||

| Current Alcohol misuse | 43% (n=101) | 31% (n=47) | 5.7214 | 0.0168 | 24% (n=54) | 19% (n=90) | 3.3614 | 0.0667 |

|

| ||||||||

| Current Drug misuse * | 17% (n=51) | 8% (n=16) | 7.0726 | 0.0029 | 4% (n=12) | 1% (n=8) | 6.8499 | 0.0055 |

|

| ||||||||

| Suicidal Since Deployment * | 14% (n=44) | 3% (n=5) | 18.4819 | <.0001 | 1% (n=4) | 0.3% (n=2) | 3.4542 | 0.0691 |

|

| ||||||||

| Recent Suicidal Ideation | 33% (n=76) | 17% (n=26) | 11.0290 | 0.0009 | 6% (n=13) | 3% (n=13) | 4.5624 | 0.0327 |

|

| ||||||||

| Severe Violence Past Year | 21% (n=48) | 19% (n=28) | 0.2294 | 0.6320 | 10% (n=23) | 4% (n=19) | 11.2641 | 0.0008 |

|

| ||||||||

| Other Physical Aggression Past Year | 58% (n=137) | 35% (n=53) | 19.6607 | <.0001 | 33% (n=73) | 19% (n=93) | 15.5854 | <.0001 |

Note.

Fisher’s Exact Chi-Square used for small cell size.

Table 3 shows that veterans with low income (below median of $50,000 annual) and poor money management skills endorsed the most problems with post-deployment adjustment, whereas those with high income (above median of $50,000 annual) and good money management skills reported the fewest problems. The ‘low income/good money management’ and ‘high income/poor money management’ groups exhibited virtually the same frequency of post-deployment adjustment problems.

TABLE 3.

Interaction between Annual Income and Money Management on Post-Deployment Adjustment Problems

| A | B | C | D | Chi-Square | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Income/Poor Money Management n=264 | Low Income/Good Money Management n=256 | High Income/Poor Money Management n=166 | High Income/Good Money Management n=417 | |||

| Severe Violence in Past Year | 23% (n=57) | 10% (n=26) | 10% (n=16) | 5% (n=20) | 47.9925 | <.0001 |

| Suicidal Since Deployment* | 9% (n=32) | 4% (n=14) | 2% (n=5) | 1% (n=4) | 41.3076 | <.0001 |

| Other Physical Aggression in Past Year | 55% (n=146) | 30% (n=77) | 33% (n=54) | 19% (n=81) | 95.6745 | <.0001 |

| Recent Suicidal Ideation | 20% (n=53) | 14% (n=36) | 11% (n=19) | 5% (n=23) | 34.5522 | <.0001 |

| Current Alcohol misuse | 38% (n=101) | 26% (n=67) | 23% (n=38) | 22% (n=90) | 24.6049 | <.0001 |

| Current Drug misuse | 14% (n=37) | 6% (n=15) | 8% (n=14) | 3% (n=11) | 33.6282 | <.0001 |

| Homeless Since Deployment * | 14% (n=46) | 2% (n=6) | 2% (n=4) | 0.4% (n=2) | 99.7498 | <.0001 |

| Arrested Since Deployment | 18% (n=46) | 9% (n=23) | 8% (n=14) | 4% (n=16) | 36.7591 | <.0001 |

Note

Fisher’s Exact Chi-Square used for small cell size.

To examine the association between the financial variables and post-deployment adjustment problems while controlling for covariates, we conducted multiple logistic regression in which variables were only included if they were statistically significant (p<.05). Readers can contact authors if interested in getting the complete results for all variables. The strength of the association is represented by Odds Ratios (OR), which if above 1 connotes increased odds and if below 1 connotes decreased odds. For each, the 95% confidence intervals (CI) of odds ratios are provided, as well.

All eight post-deployment adjustment problems assessed in this study were significantly related to financial characteristics of veterans. Homelessness was associated with lower income (OR=0.27, CI=0.13–0.56, p<0.001), having lights or power shut off in the past year (OR=4.14, CI=1.86–9.26, p<0.001), and perceived lack of financial security (OR=0.70, CI=0.59–0.83, p<0.001). Criminal arrests were linked to job loss in the past year (OR=2.22, CI=1.32–3.73, p=0.025) and having been referred to a collection agency (OR=1.97, CI=1.21–3.20, p=0.006). Alcohol abuse was related to being referred to a collection agency (OR=1.51, CI=1.08–2.12, p=0.017), while drug misuse was predicted by reports of bounced checks in the past year (OR=2.74, CI=1.57–4.78, p=0.0004).

Severe violence was also associated with referral to a collection agency (OR=1.67, CI=1.07–2.61, p=0.025), and other physical aggression was related to costs as a barrier to obtaining mental health care (OR=1.50, CI=1.13–2.20, p=0.0057), having checks bounced in the past year (OR=1.52, CI=1.01–2.29, p=0.046), and being referred to a collection agency (OR=2.20, CI=1.57–3.09, p<.0001). Post-deployment suicidal ideation was related to being unable to afford the cost of basic needs (OR=0.44, CI=0.27–0.70, p<.001) and electrical service being shut off(OR=1.94, CI=1.24–3.04, p=0.0038). Self-harm behavior was associated with being unable to afford the cost of basic needs (OR=0.22, CI=0.10–0.82, p=.019) and electrical service being shut off (OR=3.4, CI=1.43–8.255, p=.0057). These findings provide empirical support to several of the links in the pathways hypothesized in Figure 1 between financial strain and post-deployment adjustment problems.

Discussion

This study documents a strong association between post-deployment adjustment and financial well-being among Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans. The analysis shows lower income and employment among veterans with PTSD, MDD, or TBI, consistent with other research on veterans in the United States36 and United Kingdom20 and in civilian populations.37 At the same time, the data indicated that regardless of diagnosis, veterans who lacked the money needed to meet basic needs were more likely to be arrested, be homeless, misuse alcohol and drugs, demonstrate suicidal behavior, or engage in aggression post-deployment.

Although financial variables were related to adverse outcomes, the data underscored that merely increasing income may not be enough to erase post-deployment adjustment problems: the more robust predictors involved indicators of money mismanagement such as debt, writing bad checks, not paying for basic needs including utilities, and being referred to a collection agency. Importantly, these variables still predicted poor outcome when modeled with individual demographics, military characteristics, and clinical diagnosis. Finally, we found that Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans with higher income but poor money management fared about the same as those with lower income and good money management, emphasizing the dual importance of income and financial management skills.

Despite these findings, it is crucial to note that the cross-sectional nature of this study leaves unresolved the causal link between financial problems and post-deployment adjustment. Specifically, this study cannot resolve whether financial problems cause post-deployment adjustment or vice versa. Thus, it may be that financial troubles lead to post-deployment adjustment problems such as homelessness, and that the inability to afford treatment can impede access to mental health services leading to exacerbation of symptoms. However, it may also be that post-adjustment problems lead to financial problems. For example, symptoms of PTSD or MDD could interfere with work attendance and reduce stable employment. In addition, adaptive combat behaviors may be unacceptable in civilian settings, leading to lost income stemming from dissolution of relationships or social support, or even arrests and incarceration. Depression, suicidal ideation, and cognitive dysfunction can also increase the likelihood of decreased productivity, job performance, and job loss.

A third possibility raised by the data is that these pathways co-occur; financial strain and post-deployment are mutually reinforcing, and can create a downward spiral for veterans’ readjustment. Consider a veteran returning from Iraq who needs to pay back debts incurred while deployed. As a civilian, the veteran now has to find a stable job or be retrained for civilian/private-sector employment. However, the veteran may be unable to work immediately if he or she is experiencing symptoms associated with PTSD, MDD, or TBI and may incur additional debts. Increasing debt could contribute to family stress or loss of self-esteem if the veteran cannot adequately contribute to the household. The stress, in turn, may exacerbate symptoms. Problems such as suicidal ideation or physical aggression may emerge, making it even more difficult for the veteran to participate in work or school. Thus, to the extent that financial difficulties and post-deployment adjustment affect one another, policies and educational interventions that address financial literacy38,39 or employment40,41 may be as important as other clinical interventions in reducing post-deployment adjustment problems.

Veterans returning from deployment face the same financial challenges experienced by civilians. However, this study highlights that they may experience additional financial difficulties related to their combat exposure, military training, service connection, multiple deployments, and psychological or cognitive war injury. All of the eight post-deployment adjustment problems examined in our study were significantly related to the financial characteristics of veterans, even after controlling for a wide array of covariates.

It was also noteworthy that veterans with emotional problems had co-occurring financial problems. Money mismanagement and the use of funds to purchase alcohol and drugs occurred more frequently among veterans with disabilities, who typically have the fewest financial resources. Veterans with psychiatric disabilities were also at highest risk of financial exploitation and more likely to have been laid off or fired, which mirrors research findings in civilian populations.42,43 Given these findings, improved money management appears to be important for successful post-deployment adjustment, particularly for veterans with psychiatric and cognitive disabilities, and this topic could be readily (and fruitfully) addressed by the military and VA when soldiers return home.

Limitations in the study should be noted. Although some of the characteristics of nonresponders were unknown (e.g., we did not obtain economic status of nonparticipants), given the lack of substantial differences between responders and nonresponders, and the similarities between the sample and the post-9/11 military population in terms of military branch and race/ethnicity distributions, the current survey does appear to be among one of the most representative to date of Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans. Although we used Fisher’s Exact Test for small cells, a larger sample size could have improved ability to detect differences in these cases. Additional limitations include reliance on self-report and use of cross-sectional data, which restricted causal interpretation. PTSD and MDD were measured with tools based on validation studies whereas TBI was measured based on expert consensus criteria and did not include indices of symptoms. Future research should examine more closely severity and characteristics of TBI and financial well-being in veterans. More study is needed to closely examine the effects of civilian employment and VA disability compensation on post-deployment adjustment. Nonetheless, the current study takes a first step in documenting the complex and potentially deleterious impact of financial strain on post-deployment adjustment among Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans.

TABLE 1.

Financial Status and Psychological Injuries in Iraq/Afghanistan War Veterans

| Screened Positive for MDD, PTSD, or TBI (n= 387) | Screened Negative for MDD, PTSD, or TBI (n=715) | Chi-Sqr | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has Money to Cover : | ||||

| Food | 81% (n=314) | 95% (n=681) | 57.4357 | <.0001 |

| Clothing | 66% (n=253) | 90% (n=641) | 96.7373 | <.0001 |

| Housing | 81% (n=313) | 93% (n=664) | 35.5632 | <.0001 |

| Medical Care | 65% (n=251) | 85% (n=604) | 55.1509 | <.0001 |

| Social Activities | 43% (n=167) | 73% (n=520) | 93.0746 | <.0001 |

| Transportation | 58% (n=224) | 82% (n=582) | 70.8869 | <.0001 |

| All of above | 39% (n=152) | 69% (n=489) | 87.6971 | <.0001 |

| In past year: | ||||

| Lost a job | 22% (n=83) | 9% (n=61) | 36.3169 | <.0001 |

| Bad Check | 24% (n=90) | 10% (n=72) | 34.5683 | <.0001 |

| Referred to collection agency | 33% (n=127) | 14% (n=95) | 58.6980 | <.0001 |

| Lights turned off | 10% (n=38) | 2% (n=14) | 32.9399 | <.0001 |

| Victim of Scam | 6% (n=21) | 3% (n=20) | 4.6201 | 0.0316 |

| Other Financial Data | ||||

| Income> $50000? % Yes | 37% (n=144) | 61% (n=437) | 57.5604 | <.0001 |

| Unsecured Debt> $40000? %Yes | 13% (n=51) | 8% (n=55) | 8.9586 | .003 |

| Employed Past Year? %Yes | 68% (n=262) | 84% (n=599) | 37.0906 | <.0001 |

| Satisfied with Financial Status? | 52% (n=199) | 84% (n=602) | 135.8390 | <.0001 |

| Receives VA Disability Benefits? | 56% (n=213) | 25% (n=172) | 105.8156 | <.0001 |

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our sincere thanks to the participants who volunteered for this study. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institutes of Health, or the Department of Education.

Funding Source:

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by the Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, the Office of Research and Development Clinical Science, Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH080988), and the Department of Education, National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (H133G100145).

Footnotes

Please note there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Strumpel B. Economic means for human needs. Institute for Social Research; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porter NM, Garman ET. Money as a measure of financial well-being. American Behavioral Scientist. 1992;35:820–826. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Commission of Financial Literacy and Education. Promoting Financial Success in the United States: National Strategy for Financial Literacy. Washington, D.C: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sayers SL, Farrow VA, Ross J, Oslin DW. Family problems among recently returned military veterans referred for a mental health evaluation. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009 Feb;70(2):163–170. doi: 10.4088/jcp.07m03863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McFarlane AC. Military deployment: The impact on children and family adjustment and the need for care. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2009 Jul;22(4):369–373. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832c9064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine. Returning home from Iraq and Afghanistan: Preliminary assessment of readjustment needs of veterans, service members, and their families. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoge CW, Castro C, Messer S, McGurk D, Cotting D, Koffman R. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan: Mental health problems and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351(1):13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanielian T, Jaycox L. Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Santa Monica (CA): RAND Corp; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenkins R, Bhugra D, Bebbington P, et al. Debt, income and mental disorder in the general population. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38(10):1485–1493. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black RA, Rounsaville BJ, Rosenheck RA, Conrad KJ, Ball SA, Rosen MI. Measuring money mismanagement among dually diagnosed clients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2008;196(7):576–579. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31817d0535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marmot MG. Inequalities in health. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:134–136. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Copeland LA, Miller AL, Welsh DE, McCarthy JF, Zeber JE, Kilbourne AM. Clinical and demographic factors associated with homelessness and incarceration among VA patients with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Public Health. 2009 May;99(5):871–877. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.149989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA. Jail incarceration, homelessness, and mental health: A national study. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:170–177. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegel CE, Samuels J, Tang DI, Berg I, Jones K, Hopper K. Tenant outcomes in supported housing and community residences in New York City. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(7):982–991. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenheck R, Frisman L, Chung AM. The proportion of veterans among homeless men. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:466–469. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.3.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kertesz SG, Weiner SJ. Housing the chronically homeless: High hopes, complex realities. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301(17):1822–1824. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zoroya G. Jobless rates for young and female vets climbed in late 2011. USA Today. 2012 Jan 8;2012 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riddle MS, Sandersa JW, Jones JJ, Webb SC. Self-reported combat stress indicators among troops deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: An epidemiological study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2008 Jul;49(4):340–345. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beckham JC, Becker ME, Hamlett-Berry KW, et al. Preliminary findings from a clinical demonstration project for veterans returning from Iraq or Afghanistan. Military Medicine. 2008;173(5):448–451. doi: 10.7205/milmed.173.5.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iversen A, Nikolaou V, Greenberg N, et al. What happens to British veterans when they leave the armed forces? European Journal of Public Health. 2005 Apr;15(2):175–184. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Defense Manpower Data Center. FY2009 Annual Demographic Profile of Military Members in the Department of Defense and US Coast Guard. Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method. 3. New York: John Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrans CE, Powers MJ. Psychometric assessment of the Quality of Life Index. Research in Nursing & Health. 1992 Feb;15(1):29–38. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770150106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehman AF. The well-being of chronic mental patients: Assessing their quality of life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1983;40:369–373. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790040023003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marson DC, Savage R, Phillips J. Financial capacity in persons with schizophrenia and serious mental illness: Clinical and research aspects. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:81–91. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skinner HA. The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addictive Behaviors. 1982;7:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradley KA, Bush KR. Screening for problem drinking: comparison of CAGE and AUDIT. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1998;13(6):379–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steadman HJ, Silver E, Monahan J, et al. A classification tree approach to the development of actuarial violence risk assessment tools. Law and Human Behavior. 2000 Feb;24(1):83–100. doi: 10.1023/a:1005478820425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davidson JRT, Book SW, Colket JT, et al. Assessment of a new self-rating scale for posttraumatic stress disorder: The Davidson Trauma Scale. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:153–160. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonald SD, Beckham JC, Morey RA, Calhoun PS. The validity and diagnostic efficiency of the Davidson Trauma Scale in military veterans who have served since Sept 11th, 2001. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruff RM, Iverson GL, Barth JT, Bush SS, Broshek DK. Recommendations for diagnosing a mild traumatic brain injury: A National Academy of Neuropsychology education paper. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2009;24(1):3–10. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acp006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1967;6(4):278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001 Sep;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agresti A. An Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zivin K, Bohnert ASB, Mezuk B, et al. Employment status of patients in the VA health system: Implications for mental health services. Psychiatric Services. 2011 Jan;62(1):35–38. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.1.pss6201_0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cook JA. Employment barriers for persons with psychiatric disabilities: Update of a report for the President’s Commission. Psychiatric Services. 2006 Oct;57(10):1391–1405. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.10.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pang MF. Boosting financial literacy: Benefits from learning study. Instructional Science. 2010 Nov;38(6):659–677. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allen SF, Miller J. A community initiative to support family financial well-being. Community, Work & Family. 2010 Feb;13(1):89–100. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenheck RA, Mares AS. Implementation of supported employment for homeless veterans with psychiatric or addiction disorders: Two-year outcomes. Psychiatric Services. 2007 Mar;58(3):325–333. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Penk W, Drebing CE, Rosenheck RA, Krebs C, Van Ormer A, Mueller L. Veterans Health Administration transitional work experience vs. job placement in veterans with co-morbid substance use and non-psychotic psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2010;33(4):297–307. doi: 10.2975/33.4.2010.297.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elbogen EB, Tiegreen J, Vaughan C, Bradford D. Money management, mental health, and psychiatric disability: A recovery-oriented model for improving financial skills. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2011;34:223–231. doi: 10.2975/34.3.2011.223.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hill RP, Kozup JC. Consumer experiences with predatory lending practices. Journal of Consumer Affairs. 2007 Sum;41(1):29–46. [Google Scholar]