Abstract

Context

The nature of the relationship of dissociation to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is controversial and of considerable clinical and nosological importance.

Objective

To examine evidence for a distinct subtype of PTSD characterized by high levels of dissociation.

Design

A latent profile analysis of cross-sectional data from structured clinical interviews indexing DSM-IV symptoms of current PTSD and dissociation.

Setting

VA Boston and New Mexico VA Healthcare Systems.

Participants

492 Veterans and their intimate partners, all of whom had histories of trauma. Participants reported exposure to a variety of traumatic events including combat, childhood physical and sexual abuse, partner abuse, motor vehicle accidents, and natural disasters, with most participants reporting exposure to multiple types of traumatic events. Forty-two percent of the sample met criteria for a current diagnosis of PTSD.

Main Outcome Measures

Item-level scores on the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale.

Results

A latent profile analysis suggested a three class solution: a low severity subgroup, a high PTSD severity subgroup characterized by elevations across the 17 core symptoms of the disorder, and a small but distinctly dissociative subgroup that comprised 12% of individuals with a current diagnosis of PTSD. The latter group was characterized by severe PTSD symptoms combined with marked elevations on items assessing flashbacks, derealization, and depersonalization. Individuals in this subgroup also endorsed greater exposure to childhood and adult sexual trauma compared to the other two groups suggesting a possible etiologic link with the experience of repeated sexual trauma.

Conclusions

Results support the subtype hypothesis of the association between PTSD and dissociation and suggest that dissociation is a highly salient facet of posttraumatic psychopathology in a subset of individuals with the disorder.

Symptoms of dissociation are thought to play an important role in the development and maintenance of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and related disorders. Peritraumatic dissociation is a diagnostic criterion for acute stress disorder and has been shown to prospectively predict the development of PTSD.1, 2 Dissociative symptoms can also co-occur with PTSD and are thought to interfere with the emotional activation and processing necessary for successful treatment with prolonged exposure therapy.3, 4 Though the relationship of dissociation to PTSD is of considerable clinical and nosological importance, the nature of the association between these phenomena remains a source of controversy. One empirically testable model for this association proposes that dissociation is primarily characteristic of a distinct subset, or subtype of individuals with PTSD.5–10 The primary aim of this study was to evaluate this hypothesis using latent class analysis in a large sample of trauma-exposed Veterans and their trauma-exposed partners.

The dissociative subtype hypothesis posits that dissociation is present primarily in a distinct subset of individuals with PTSD and is characterized by blunted or inhibited emotional and physiological responses to internal and external trauma-related stimuli.10 Prior studies using taxometric analysis,9 examination of the distribution of dissociative symptoms,8 and signal detection analysis,7 have provided preliminary support for this hypothesis. For example, Waelde, Silvern, & Fairbank9 performed taxometric analyses on items from the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES11) drawn from a sample of trauma-exposed Vietnam Veterans. Results provided evidence for a discontinuous distribution of DES scores and a distinct subgroup, or taxon, of cases at the severe end of that distribution who also exhibited elevated levels of PTSD.

The aim of this study was to replicate and extend these findings using latent class analysis, a contemporary approach to the multivariate evaluation of typological hypotheses. Latent profile analysis (LPA) is a form of latent class analysis used in the evaluation of continuous (i.e., dimensional) observed scores and partitions cases in a dataset into latent, or unobserved, categorical classes. Thus, LPA defines homogenous subgroups of individuals within a dataset based on broad characteristics that are not directly measured. In this study, clinical interview-based data on the 17 core DSM-IV PTSD symptoms along with 3 items reflecting dissociation from the associated features section of the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS12) were analyzed.

This study also provided an opportunity to evaluate the relationship between trauma exposure, dissociation, and PTSD as trauma is thought to play a primary etiologic role in the development of both PTSD and dissociation. In the case of dissociation symptoms, repeated and severe early childhood trauma has been theorized to disrupt the normal development, consolidation, and integration of personality and cognitive processes, leading to the development and persistence of dissociative symptoms into adulthood.13–16 Childhood emotional maltreatment (i.e., psychological abuse and neglect) has also been shown to be associated with dissociation in adulthood.17, 18 However, it is not clear that dissociation is uniquely associated with early developmental trauma, as dissociation has also been reported in samples of individuals exposed to adult trauma, including combat,19, 20 and major accidents.21 Thus, a second aim of this study was to compare the association between different types of trauma and dissociation.

One limitation of prior research in this area is that most studies have relied on self-report measures of dissociative symptoms such as the DES.11, 22 Critics have raised concerns about the construct validity, longitudinal stability, and predictive utility of the measure.23 Though efforts have been undertaken to improve the DES, critics have argued that revised versions (i.e., the DES-Taxon24) still do not adequately identify those with dissociative disorders and may be unduly influenced by non-pathological, or normative experiences that fall along the boundary of pathological dissociation.25 This study utilized a structured clinical interview administered by trained clinicians to quantify the prevalence of dissociation, as defined as reduction in awareness of surroundings, derealization, and depersonalization, in individuals with trauma histories, so as to better examine the association between dissociation and PTSD.

Aims and Hypotheses

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate evidence for a dissociative subtype of posttraumatic psychopathology. We hypothesized that a LPA of the core PTSD and dissociative symptoms would yield evidence of a distinct subtype characterized by elevated levels of dissociation and specific PTSD symptoms that are conceptually linked to dissociation, namely: flashbacks (B3), psychogenic amnesia (C3), and emotional numbing (C6). We also evaluated potential demographic and trauma exposure correlates of dissociation and predicted that individuals in the dissociative subgroup would show higher mean scores on an index of childhood sexual abuse compared to those without dissociation.

Method

Participants

Participants were 559 Veterans and their spouses or intimate partners who enrolled in recent studies at U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. Of these, 18 were omitted from analyses because they withdrew from study participation and 15 were terminated by study staff due to problems conforming to interview requirements, yielding a subsample of 526 study completers. Of these, 64% were male and 73% were Veterans; the mean age of the sample was 51.3 (range: 21–75). One hundred sixty-six participants were cohabitating intimate partners of Veterans who were recruited into the study along with their veteran partner. Individuals self-reported their race and ethnicity as follows: 82% White, 13% Black or African American, 8% American Indian or Alaskan Native, 4% race unknown and less than 1% reported being Asian or Pacific Islander; in addition, 13% reported their ethnicity as Hispanic or Latino. As this study focused on psychopathological responses to trauma, only data from individuals (Veterans or their partners) who reported trauma exposure, as defined by DSM-IV PTSD Criterion A, were included in the data analyses (n = 492, 94% of the full sample). We included Veterans and their partners because doing so increased our sample size, yielded more statistical power, and improved the study generalizability by extending the work to trauma-exposed women and non-Veterans.

Procedure

This research was reviewed and approved by the appropriate human subjects and scientific review boards, namely: the Institutional Review Board (human subjects) and Research and Development committees at the VA Boston Healthcare System, the Institutional Review Board at the Boston University School of Medicine, the Scientific Review Committee at the New Mexico VA Health Care System, and the Human Research Review Committee at the University of New Mexico. Participants provided written informed consent and were compensated for their time. Study participants were recruited through medical databases, flyers, clinician referrals, and a recruitment database. The procedure involved administration of a series of self-report measures and structured diagnostic interviews, including the CAPS. Interviewers were advanced psychology graduate students, postdoctoral psychology clinicians, and licensed clinical psychologists who received extensive training prior to data collection. All interviews were videotaped and 31% of the CAPS recordings were later viewed by a blind independent rater for purposes of quality control and evaluating inter-rater reliability.

Measures

The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS12)

The CAPS is a 30-item structured diagnostic interview that assesses the frequency and severity of the 17 DSM-IV PTSD symptoms and 5 associated features, including three dissociation symptoms: reduction in awareness of surroundings, derealization, and depersonalization. The CAPS was used to determine current PTSD diagnostic status using a validated DSM-IV scoring rule.26 Dimensional severity scores were calculated by summing the frequency and intensity ratings for each of the 17 items. The CAPS has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity.12, 27

Internal consistency of CAPS item severity scores in this study was high (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = .91). Inter-rater reliability based on secondary ratings of the CAPS video recordings was good (kappa = .65) for current PTSD diagnoses and excellent for current severity score ratings (intraclass correlation coefficient = .98). In addition, intraclass correlation coefficients for the three dissociation items were high (mean = .79, range: .72 – .87).

Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ28)

The TLEQ is a self-report measure that assesses exposure to 21 different events that meet the DSM-IV PTSD Criterion A1 definition for a traumatic event. For each traumatic event endorsed, a follow-up question assesses if the individual meets DSM-IV PTSD Criterion A2. The number of times the event was experienced is also assessed on a 7-point scale ranging from “never” to “more than five times.” The TLEQ exhibits good test-retest reliability over a two-week interval (mean kappa = .63, mean percent agreement = 86%), excellent content and convergent validity with interview-based measures of trauma exposure (mean percent agreement = 92%) and is predictive of PTSD status.28 In this study, we analyzed data only for traumatic events that met the DSM-IV PTSD Criteria A1 and A2.

Statistical Analyses

We first evaluated the distribution of the dissociation severity scores in the sample. Next, we used LPA to evaluate evidence for a dissociative subtype of PTSD. We submitted current (i.e., past month) item-level severity scores on the CAPS to the LPA. These scores reflect the 17 core PTSD criteria and the 3 associated features of reduction in awareness of surroundings, derealization, and depersonalization. As individuals in the dataset were nested within couples (i.e., meaning that not all observations were independent of one another), we specified this complex structure in our model script and employed a robust covariance matrix estimator so that the standard errors would not be biased by the non-independence of these observations.29–31 We began by evaluating the fit of a 2-class model and systematically increased the number of latent classes in the model until it was evident that the addition of latent classes was not warranted. To determine this, we evaluated the following indices of comparative model fit. First, the p-value associated with the the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test32 (LMR-A) was evaluated; this statistic compares the fit of the specified class solution to a model with one less class. A p-value < .05 suggests that the specified model provides a better fit to the data relative to a model with one less class. In contrast, p-values ≥ .05 suggest that a more parsimonious class solution is favored (i.e., fewer classes are needed to accurately reflect the data). An additional statistic, the bootstrap likelihood ratio test,33 has been shown to outperform the LMR-A in the selection of the correct number of classes34, but we were unable to evaluate this statistic as our efforts to account for the complex data structure meant that this statistic could not be produced by the statistical modeling program. We also evaluated the Bayesian information criterion35 (BIC), which has been shown to perform well in simulation studies.34 Lower relative values on the BIC indicate improved model fit. The LPA was conducted with the Mplus version 5.2 statistical modeling software.36 After determining the best class solution, we used latent class membership as a between-subjects variable in one-way ANOVAs and chi square analyses to examine demographic, trauma, and PTSD-symptom differences among the latent classes.

Results

Rates of PTSD and Dissociation

Forty-two percent of the full sample (50% of the Veterans and 20% of the partners) met DSM-IV criteria for current PTSD and 63% of the full sample (72% of the Veterans and 38% of the partners) met DSM-IV criteria for a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD. On the CAPS dissociation items, 27.5% of the sample met criteria for current reduction in awareness, 5.4% met for depersonalization, and 7.2% met for derealization. We evaluated the distribution of the three dissociation items and found that the scores on these items were not normally distributed (histograms available from first author). Specifically, 70% of the participants received a score of 0 on the reduction in awareness item while a greater percentage of participants (over 90%) received a severity score of 0 on the derealization and depersonalization items.

LPA of PTSD and Dissociation Symptoms

The LPA was performed on the severity scores for the 17 DSM-IV PTSD symptoms and the 3 dissociation items. The two and three class models converged fully but the four class model resulted in a failure to replicate the best loglikelihood value, despite increasing the number of random start values for this analysis. This suggests that a local maxima was reached (i.e., the best overall solution for the analysis was not obtained), that the parameter estimates may be unreliable, and that the model had attempted to extract too many classes.33 Based on this, we rejected the four class model and the two and three class models were compared more closely. As shown in Table 1, the LMR-A p-value for the three class model was not significant (suggesting that the three class model was not superior to a two class model), however, other indicators suggested the superiority of the three class model. Specifically, the three class model yielded a lower BIC, higher entropy, and good discrimination among the classes. Given this pattern of results, and given evidence that the BIC is better than the LMR-A at informing the best class solution,34 we retained the three class model as the best fitting one. In this model, 51% were classified into group 1, 43% into group 2, and 6% into group 3. The mean probability of class membership was excellent and suggested good discrimination among the classes (.98 for class 1, .98 for class 2, and .99 for class 3).

Table 1.

Fit of Competing Models

| Model | Loglikelihood | BIC | Entropy | LMR-A p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Class | −21135.515 | 42649.137 | .94 | < .001 |

| 3 Class | −20568.202 | 41644.680 | .96 | .35 |

| 4 Class | −20311.698a | 41261.839 | .96 | .67 |

Note. BIC = Bayesian information criterion; LMR-A = Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test;

The best loglikelihood value was not replicated, despite increasing the number of random starts. This can be an indication that too many classes were extracted and/or that a local maxima was reached and the parameter estimates may not be reliable or replicable.

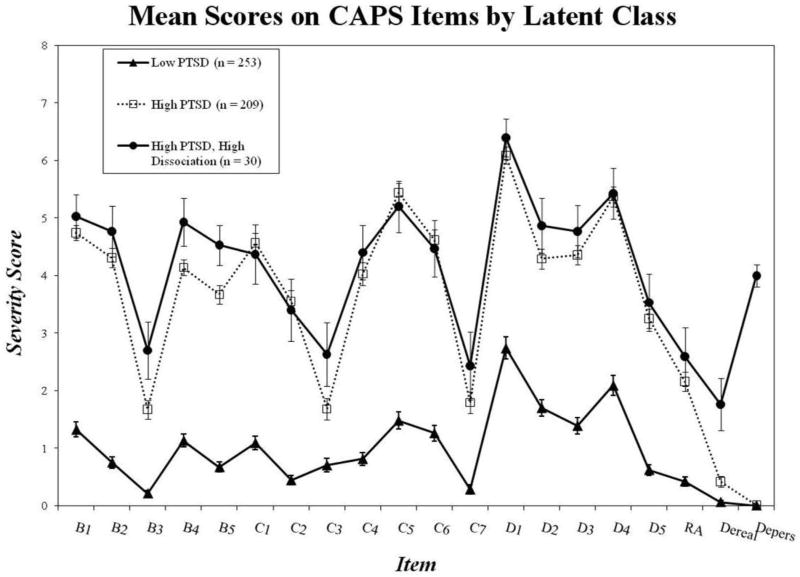

Figure 1 shows the profile of the CAPS items as a function of the three latent classes. As shown in Figure 1, class 1 tended to have very low scores on all symptoms while classes 2 and 3 had higher scores on all of the PTSD symptoms and appeared to primarily differ from one another in that class 3 scored higher on items reflecting derealization and depersonalization. Based on this pattern of results we identified class 1 as the “low PTSD” group, class 2 as the “high PTSD” group, and class 3 as the “high PTSD/high dissociation” group. Nearly twelve percent of individuals with a current diagnosis of PTSD were assigned to the latent dissociative group.

Figure 1. Mean Scores on CAPS Items by Latent Class.

Note. The Figure shows the pattern of mean PTSD and dissociative symptom severity scores on the CAPS as a function of latent class. Mean scores on PTSD criterion B3, and on the derealization and depersonalization items differed significantly between the two high PTSD groups. There was a trend to suggest a significant difference between the two high PTSD groups on PTSD criterion C3 (p = .10) and PTSD criterion B5 (p = .05). CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; RA = reduction in awareness; dereal = derealization; depers = depersonalization.

Differences in PTSD Symptoms as a Function of Latent Class Membership

We then used final class membership as a between subjects variable in ANOVAs and chi square analyses evaluating differences in PTSD symptoms as a function of latent class membership. The ANOVAs evaluating mean symptom severity differences on each of the CAPS items as a function of latent class membership were all statistically significant at the p < .001 level. Follow-up pairwise comparison’s using Tukey’s tests revealed that the majority of the overall F-tests were statistically significant as a function of the two high PTSD groups evidencing higher mean severity on each item relative to the low PTSD group. There were three instances in which pairwise comparisons revealed differences between the two high PTSD groups. Specifically, the dissociative group evidenced a mean score (M = 4.93, SD = 2.27) on PTSD Criterion B3 (flashbacks) that was greater than the high PTSD group (M = 1.67, SD = 2.28), which was in turn greater than the mean score of the low PTSD group (M =.21, SD = .83; overall F [2, 489] = 56.32, p < .001). The dissociative group also scored higher on derealization (M = 1.76, SD = 2.44) relative to the high PTSD group (M = .42. SD = 1.22), with the latter group scoring higher than the low PTSD group (M = .06, SD = .53; overall F [2, 481] = 35.13, p < .001). The dissociative group also evidenced higher mean ratings on depersonalization (M = 4.0, SD = 1.0) relative to the high PTSD group (M = .01, SD = .14) and the low PTSD group (M = 0, SD = 0), which did not differ from one another (overall F [2, 479] = 3258.69, p < .001).

Pairwise comparisons also revealed two instances in which the two high PTSD groups tended to diverge from one another, though the mean differences failed to reach the standard significance level of p < .05. Specifically, there was a statistical trend suggesting that the dissociative group scored higher on PTSD criterion B5 (trauma cued physiological reactivity) relative to the high PTSD group (M = 4.53, SD = 1.93 versus M = 3.67, SD = 2.30, respectively; p-value associated with Tukey’s comparison = .052). Similarly, there was a trend suggesting that individuals from the dissociative group scored higher on PTSD Criterion C3 (psychogenic amnesia) relative to the high PTSD group (M = 2.63, SD = 3.03 versus M = 1.68, SD = 2.70, respectively, p-value associated with Tukey’s comparison = .098).

We next evaluated the extent to which rates of PTSD differed across the latent classes. Chi square analysis revealed no differences between the rate of current PTSD diagnosis among the two high PTSD groups, however the two high PTSD groups evidenced higher rates of PTSD (80% of both groups) relative to the low PTSD group (6%), overall χ2 (2, n = 492) = 276.42, p < .001. Conversely, 11.65% of cases with a current diagnosis of PTSD fell in the dissociative group. As 20% of the dissociative group did not meet criteria for a current diagnosis of PTSD, we evaluated the severity of their symptoms and found that the mean CAPS severity score among those without PTSD in the dissociative group was 50.67 (SD = 15.38), which suggest significant PTSD symptoms even among those who failed to meet criteria for the diagnosis.

Demographic and Trauma Exposure Differences between the Latent Classes

Chi square tests revealed demographic differences among the three latent classes (statistics available from first author) but follow-up pairwise testing showed that these differences were limited to contrasts between the low versus high PTSD groups. There were no differences between the two high PTSD groups with respect to gender, race, ethnicity, age (as determined by ANOVA), marital status, veteran status, era of service, military branch, involvement in mental health counseling, or use of psychiatric medications.

In contrast, differences between the two high PTSD classes were found in comparisons of exposure to traumatic events that met the DSM-IV PTSD Criterion A1 and A2 definition of a traumatic event. As shown in Table 2, ANOVAs revealed that individuals in the dissociative latent class reported more childhood (prior to age 13) sexual abuse as well as more sexual abuse as an adult (age 18+) relative to the high or low PTSD classes. Differences between the two high PTSD groups were specific to the sexual abuse variables: all other trauma exposure variables evidenced differences between the low and high PTSD classes only or no group differences at all.

Table 2.

Trauma Exposure Differences Among the Three Latent Classes

| Trauma Type | % Reporting Exposure

|

# of Times Traumatic Event Occurred

|

ANOVA Results

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Sample (n = 492) | Full Sample (n = 492) M (SD) |

Group 1: Low PTSD (n = 253) M (SD) |

Group 2: High PTSD (n = 209) M (SD) |

Group 3: HighPTSD/High Diss (n = 30) M (SD) |

Overall F (df), p-value | Pairwise Comparisons | |

| Childhood Sexual Abuse | 22 | .86 (1.92) | .66 (1.65) | .95 (2.02) | 1.90 (2.81) | 5.91 (2, 482), p = .003 | 3 > 2 & 1 |

| Childhood Phys Abuse | 35 | 1.73 (2.58) | 1.29 (2.34) | 2.28 (2.76) | 1.67 (2.67) | 8.32 (2, 481), p < .001 | 2 > 1 |

| Adult Sexual Abuse | 15 | .37 (1.13) | .24 (.78) | .44 (1.31) | .97 (1.83) | 6.34 (2, 479), p = .002 | 3 > 2 > 1 |

| Phys Abuse by Partner | 26 | .90 (1.83) | .81 (1.71) | .90 (1.83) | 1.66 (2.58) | 2.81 (2, 485), p = .06 | |

| Combat | 38 | 1.86 (2.61) | 1.16 (2.20) | 2.48 (2.78) | 3.37 (2.92) | 21.57 (2, 486), p < .001 | 3 & 2 > 1 |

| Armed Robbery | 29 | .53 (1.03) | .46 (.99) | .62 (1.10) | .47 (.86) | 1.38 (2, 483), p = .25 | |

| Natural Disaster | 31 | .93 (1.66) | .61 (1.35) | 1.23 (1.85) | 1.47 (2.08) | 9.98 (2, 485), p < .001 | 3 & 2 > 1 |

| Motor Vehicle Accident | 33 | .62 (1.11) | .43 (.84) | .84 (1.33) | .77 (1.22) | 8.45 (2, 485), p < .001 | 2 > 1 |

| Number of Diff Traumas | N/A | 7.07 (4.22) | 5.91 (3.69) | 8.11 (4.30) | 9.70 (4.95) | 23.77 (2, 488), p < .001 | 3 & 2 > 1 |

Note. Possible range on specific trauma exposure variables: 0 to 6. Possible range of number of different traumas: 0 – 23. Diss = dissociation; Diff = different.

Association between Dissociation and PTSD Severity

We also examined correlations between overall PTSD severity (a summary score of the 17 PTSD items on the CAPS), the PTSD symptom cluster severity scores (i.e., reexperiencing, avoidance and numbing, and hyperarousal), dissociation severity (a summary score of the three dissociation items), and severity scores on the three individual dissociation items. As shown in Table 3, overall PTSD severity was moderately correlated with severity scores for the reduction in awareness item (r = .46, p < .001), but showed weak associations with the derealization and depersonalization CAPS items (both rs = .27, ps < .001). Neither derealization nor depersonalization correlated strongly with any of the PTSD symptom clusters (strongest r = .27) while the PTSD symptom clusters showed high levels of covariation with each other (mean r = .69). The dissociation severity summary score showed moderate associations (in the r = .42 - .50 range) with each PTSD variable but this appeared to be largely influenced by scores on the reduction in awareness item, relative to scores on the depersonalization and derealization items. This was evidenced by the greater magnitude of association between the reduction in awareness item and the dissociation summary score (r = .84) relative to that for depersonalization (r = .54) or derealization (r = .68).

Table 3.

Pearson Correlations among PTSD and Dissociative Symptoms

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PTSD Severity | -- | ||||||

| 2. B Sx | .87 | -- | |||||

| 3. C Sx | .92 | .70 | -- | ||||

| 4. D Sx | .88 | .67 | .71 | -- | |||

| 5. Dissociation Sx | .50 | .42 | .46 | .46 | -- | ||

| 6. Reduction in Awareness | .46 | .36 | .43 | .44 | .84 | -- | |

| 7. Derealization | .27 | .23 | .26 | .23 | .68 | .30 | -- |

| 8. Depersonalization | .27 | .27 | .23 | .22 | .54 | .13 | .33 |

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; Sx = symptoms; B = reexperiencing; C = avoidance and numbing; D = hyperarousal. The Dissociation Sx variable is a summary score of the three individual dissociation items evaluated in this study.

LPA of PTSD and Dissociation Symptoms in Individuals with Current PTSD

Finally, we also conducted the LPA in the subset of participants who met DSM-IV criteria for current PTSD (n = 206). We ran this analysis in a manner analogous to the main analyses, controlling for the non-independence of individuals nested within the same couple. The results were unchanged from that using the full sample and the percent of individuals in the dissociative group was equivalent to that for individuals with PTSD when evaluated in the full sample. Specifically, the analysis of participants with current PTSD suggested that 49% of this group were classified into a moderate PTSD group, 40% were classified into a high PTSD group, and 11.5% were classified into a high PTSD/high dissociative group (details available from first author).

Discussion

This study examined the nature of the association between symptoms of dissociation and PTSD. A latent class analysis of CAPS data drawn from a sample of trauma-exposed Veterans and their partners yielded evidence for a three class solution: a low severity class, a high PTSD severity class, and a small (n = 30 or 6% of the entire sample) but distinctly dissociative class. The latter group was characterized by severe PTSD symptoms combined with significant elevations on items assessing flashbacks, derealization, and depersonalization. Individuals in this subgroup also endorsed greater exposure to childhood and adult sexual trauma compared to the other two groups suggesting a possible etiologic link with the experience of repeated sexual trauma. Eighty percent of individuals in the dissociative class met criteria for current PTSD and this subgroup represented approximately 12% of cases with a current diagnosis of PTSD.

Findings of this study contribute to a growing body of research suggesting that dissociative symptoms are symptomatic of a distinct subtype (or taxon) of individuals with posttraumatic psychopathology. This study replicates and extends findings reported by Waelde, Silvern, and Fairbank9 who performed taxometric analyses of DES scores and found evidence for a dissociative subtype characterized by elevated levels of PTSD. As in this study, the proportion of the overall sample assigned to the dissociative taxon was small (9.5% compared to 6% in this study), though the proportion of cases with PTSD was higher in that study (32% in the study by Waelde and colleagues;9 12% in this one). One possible explanation for this difference is that the Waelde et al. study used the DES as the measure of dissociation, which has been shown to be sensitive to non-pathological forms of dissociation. This might inflate the percentage of individuals assigned to the dissociative class relative to our study, which was based on a clinician rated measure of dissociation.

Analyses that examined the bivariate associations between PTSD symptom clusters and dissociation showed weak correlations between PTSD and the derealization and depersonalization items, which largely defined the dissociative subtype. In contrast, the PTSD symptom clusters showed high levels of inter-correlation. This pattern of results appears inconsistent with the notion that dissociation is an essential facet of PTSD for all or most individuals with the disorder, since that hypothesis would predict that dissociation and PTSD symptoms would be more highly inter-correlated. Instead, our results suggest that dissociation is highly salient for a subset of individuals with PTSD. Prior studies that have evaluated the evidence for a linear relationship between PTSD and dissociation have yielded mixed results with some studies showing a strong correlation between symptoms of dissociation and PTSD (i.e., in the r = .60 range5, 37–40) and other work failing to demonstrate this association.20 Future research should aim to clarify the relationship between PTSD and dissociation using psychometric methods for establishing the convergent and discriminant validity of psychological constructs.

This study could not address questions about the extent to which the dissociative subtype was associated with poorer response to PTSD treatment. Although this subtype would be expected to have difficulty accessing and processing the trauma-related memory and emotions that are common elements of successful PTSD treatment,3,4 research designed to evaluate this hypothesis has failed to find support for it.41 Specifically, work by Hagenaars and colleagues41 demonstrated that while individuals with PTSD and high levels of dissociation tended to score higher on PTSD severity at both pre- and post-treatment relative to individuals who were low on dissociation, and were also more likely to retain the PTSD diagnosis at post-treatment, both groups responded equally well to PTSD treatment. In other words, there was no evidence for a group by time interaction effect; this type of interactive effect is necessary to demonstrate that individuals in the dissociative class were less responsive to PTSD treatment. However, failure to find an association between dissociation and treatment response cannot conclusively demonstrate the lack of such an association (i.e., one can never prove the null hypothesis); therefore, additional study of this issue is warranted.

While all the dissociation items that were evaluated in this study occurred rarely in the sample, only derealization and depersonalization distinguished the dissociative group from the other groups and we did not find an association with emotional numbing as predicted by some models of dissociation.10 The CAPS item reflecting a reduction in awareness was endorsed more frequently than the other two dissociative items and was associated with both the high PTSD and the dissociative groups, whereas derealization and depersonalization were characteristic of the dissociative group only. This suggests that it is important to distinguish between normative and pathological dissociation. Normative dissociation has been linked to the construct of absorption42 and is conceptualized as a cognitive trait that is distributed normally in the population. In contrast, derealization and depersonalization reflect a pathological form of dissociation associated with psychiatric diagnoses and functional impairment.24 In this study, these symptoms co-occurred with flashbacks and were linked to greater reports of sexual abuse. This pattern of results is broadly consistent with Janet’s43 original conceptualization of the distinction between pathological and nonpathological dissociation and the etiologic role of early trauma in the former.

Limitations and Conclusions

The findings of this study should be considered in light of its limitations. The dissociation assessment was limited to items contained in the CAPS so its scope was circumscribed compared to longer measures and it would have been useful to evaluate the robustness of our findings using a supplementary measure of dissociation. Another limitation was that trauma was assessed retrospectively via self-report so conclusions about causal links to dissociation should be interpreted with caution. In addition, not all participants in the study met criteria for a current or lifetime PTSD diagnosis and this raises questions about the specificity of these results to the PTSD population and suggests that the dissociative group may be more accurately described as a subtype of individuals with posttraumatic psychopathology. However, evidence that the same pattern of results emerged when evaluated in our subsample of individuals with current PTSD should help to mitigate this concern and demonstrate the relevance of the subtype to the PTSD population specifically. Study generalizability was limited by the exclusive focus on Veterans and their partners and it is possible that the inclusion of non-independent observations may have affected the results, despite our efforts to account for this statistically. Finally, it is possible that the low base rate of dissociative symptoms in this sample restricted the range of scores on such symptoms, resulting in an attenuated relationship between dissociation and PTSD. Despite these limitations, findings of this study provide empirical support for a small but distinct dissociative subtype of PTSD defined by marked elevations in depersonalization, derealization, and flashbacks combined with greater reports of childhood and adult sexual trauma.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by National Institute on Mental Health award RO1 MH079806 and a VA Merit Review Grant awarded to Mark Miller and by a VA Career Development Award to Erika Wolf.

Erika J. Wolf, National Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System & Department of Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine; Mark W. Miller, National Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System & Department of Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine; Annemarie F. Reardon, National Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System; Karen Ryabchenko, PhD, VA Boston Healthcare System; Diane Castillo, VA New Mexico Healthcare System; Rachel Freund, VA New Mexico Healthcare System

Footnotes

None of the authors of this manuscript have a conflict of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Erika J. Wolf, National Center for PTSD at VA Boston Healthcare System & Boston University School of Medicine

Mark W. Miller, National Center for PTSD at VA Boston Healthcare System & Boston University School of Medicine

Annemarie F. Reardon, National Center for PTSD at VA Boston Healthcare System

Karen A. Ryabchenko, VA Boston Healthcare System

Diane Castillo, VA New Mexico Healthcare System

Rachel Freund, VA New Mexico Healthcare System

References

- 1.Ehlers A, Mayou RA, Bryant B. Psychological predictors of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder after motor vehicle accidents. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107(3):508–519. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.107.3.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2008;S(1):3–36. doi: 10.1037/1942-9681.S.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foa EB, Kozak MJ. Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychol Bull. 1986;99(1):20–35. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.99.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaycox LH, Foa EB, Morral AR. Influence of emotional engagement and habituation on exposure therapy for PTSD. J Consult Clin Psych. 1998;66(1):185–192. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson EB, Dalenberg C, McDade-Montez E. Dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder: recommendations for modifying the diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Psychol Trauma. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bremner JD. Acute and chronic responses to psychological trauma: where do we go from here? Am J Psychiat. 1999;156:349–351. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ginzburg K, Koopman C, Butler LD, Palesh O, Kraemer HC, Classen CC, Spiegel D. Evidence for a dissociative subtype of post-traumatic stress disorder among help-seeking childhood sexual abuse survivors. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2006;7(2):7–27. doi: 10.1300/J229v07n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Putnam FW, Carlson EB, Ross CA, Anderson G. Patterns of dissociation in clinical and nonclinical samples. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1996;184(11):673–679. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199611000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waelde LC, Silvern L, Fairbank JA. A taxometric investigation of dissociation in Vietnam Veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18(4):359–369. doi: 10.1002/jts.20034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanius RA, Vermetten E, Loewenstein RJ, Brand B, Schmahl C, Bremner JD, Spiegel D. Emotion modulation in PTSD: Clinical and neurobiological evidence for a dissociative subtype. Am J Psychiat. 2010;167(6):640–647. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein EM, Putnam FW. Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986;174(12):727–735. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198612000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek D, Klauminzer G, Charney DS, Keane TM. Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) Boston, MA: National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Behavioral Science Division-Boston, VA; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu JA, Frey LM, Ganzel BL, Matthews JA. Memories of childhood abuse: Dissociation, amnesia, and corroboration. Am J Psychiat. 1999;156(5):749–755. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terr LC. Childhood traumas: An outline and overview. Am J Psychiat. 1991;148(1):10–20. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van der Hart O, Nijenhuis ERS, Steele K. Dissociation: An insufficiently recognized major feature of complex posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18:413–423. doi: 10.1002/jts.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van der Kolk BA, Pelcovitz D, Roth S, Mandel FS. Dissociation, somatization, and affect dysregulation: The complexity of adaptation to trauma. Am J Psychiat. 1996;153(Suppl):83–93. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.7.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Briere J, Runtz M. Symptomatology associated with childhood sexual victimization in a nonclinical adult sample. Child Abuse Negl. 1988;12(1):51–59. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(88)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandberg D, Lynn S. Dissociative experiences, psychopathology and adjustment, and child and adolescent maltreatment in female college students. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992;101(4):717–723. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.4.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Branscomb LL. Dissociation in combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Dissociation. 1991:413–420. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bremner J, Southwick S, Brett E, Fontana A. Dissociation and posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam combat veterans. Am J Psychiat. 1992;149(3):328–332. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baranyi A, Leithgöb O, Kreiner B, Tanzer K, Ehrlich G, Hofer H, Rothenhäusler H. Relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder, quality of life, social support, and affective and dissociative status in severely injured accident victims 12 months after trauma. Psychosomatics. 2010;51(3):237–247. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.51.3.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carlson E, Putnam FW. An update on the Dissociative Experiences Scale. Dissociation: Progress in the Dissociative Disorders. 1993;6(1):16–27. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giesbrecht T, Lynn S, Lilienfeld SO, Merckelbach H. Cognitive processes in dissociation: An analysis of core theoretical assumptions. Psychol Bull. 2007;134(5):617–647. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.5.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waller N, Putnam FW, Carlson EB. Types of dissociation and dissociative types: A taxometric analysis of dissociative experiences. Psychol Methods. 1996;1(3):300–321. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.3.300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giesbrecht T, Merckelbach H, Geraerts E. The dissociative experiences taxon is related to fantasy proneness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(9):769–772. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318142ce55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weathers FW, Ruscio A, Keane TM. Psychometric properties of nine scoring rules for the Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale. Psychol Assessment. 1999;11(2):124–133. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.11.2.124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keane TM, Brief DJ, Pratt EM, Miller MW. Assessment of PTSD and its comorbidities in adults. In: Friedman MJ, Keane TM, Resick PA, editors. Handbook of PTSD: Science and practice. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kubany ES, Haynes SN, Leisen MB, Owens JA, Kaplan AS, Watson SB, Burns K. Development and preliminary validation of a brief-broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: The Traumatic Events Life Questionnaire. Psychol Assessment. 2000;12:210–224. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muthén B, Asparouhov T. Item response mixture modeling: Application to tobacco dependence criteria. Addict Behav. 2006;31(6):1050–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henry K, Muthén B. Multilevel latent class analysis: An application of adolescent smoking typologies with individual and contextual predictors. Struct Equ Modeling. 2010;17(2):193–215. doi: 10.1080/10705511003659342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muthén BO, Satorra A. Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. Sociological Methodology. 1995;25:267–316. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lo Y, Mendell N, Rubin D. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88:767–778. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLachlan G, Peel D. Finite mixture models. New York: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Modeling. 2007;13:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 5. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; pp. 1998–2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Briere J, Scott C, Weathers F. Peritraumatic and persistent dissociation in the presumed etiology of PTSD. Am J Psychiat. 2005;162(12):2295–2301. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cloitre M, Stolbach BC, Herman JL, van der Kolk B, Pynoos R, Wang J, Petkova E. A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22(5):399–408. doi: 10.1002/jts.20444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaplow JB, Dodge KA, Amaya-Jackson L, Saxe GN. Pathways to PTSD, Part II: Sexually Abused Children. Am J Psychiat. 2005;162:1305–1310. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karatzias T, Power K, Brown K, McGoldrick T. Posttraumatic symptomatology and dissociation in outpatients with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2010;11(1):83–92. doi: 10.1080/15299730903143667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hagenaars MA, van Minnen A, Hoogduin KL. The impact of dissociation and depression on the efficacy of prolonged exposure treatment for PTSD. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48(1):19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tellegen A, Atkinson G. Openness to absorbing and self altering experiencing (“absorption”). A trait related to hypnotic susceptibility. J Abnorm Psychol. 1974;83:268–277. doi: 10.1037/h0036681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Janet P. L’Automatisme psychologique [Psychological automation] Paris: Fálix Alcan; 1889. [Google Scholar]