Abstract

The Human Genome Project and HapMap have led to a better appreciation of the importance of common genetic variation in determining cancer risk, created potential for predicting response to therapy, and made possible the development of targeted prevention and therapeutic interventions. Advances in molecular epidemiology can be used to explore the role of genetic variation in modulating the risk for severe and persistent symptoms, such as pain, depression, and fatigue, in patients with cancer. The same genes that are implicated in cancer risk might also be involved in the modulation of therapeutic outcomes. For example, polymorphisms in several cytokine genes are potential markers for genetic susceptibility both for cancer risk and for cancer-related symptoms. These genetic polymorphisms are stable markers and easily and reliably assayed to explore the extent to which genetic variation might prove useful in identifying patients with cancer at high-risk of symptom development. Likewise, they could identify subgroups who might benefit most from symptom intervention, and contribute to developing personalised and more effective therapies for persistent symptoms.

Introduction

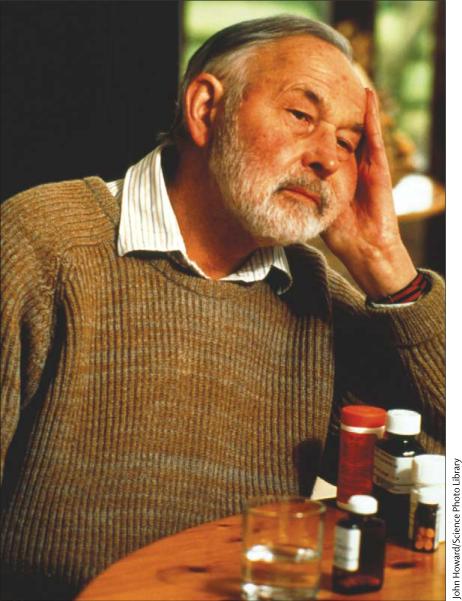

Common symptoms of cancer and cancer treatment significantly impair patients’ daily function and quality of life (figure 1).1 Severe symptoms may negatively influence treatment effectiveness by interrupting treatment. Symptoms are a subjective experience and the tools of assessment rely on patients’ self-reporting. Several scales target symptoms experienced most frequently and are most distressing to patients with cancer.2–6 Scales assessing quality of life also include multiple symptoms and have been used in many studies of symptoms (table 1).7–9

Figure 1.

Pain, depression, and fatigue associated with cancer affect quality of life

Table 1.

Multisymptom assessment and quality of life scales

| Number of Items | Dimensions | Rating | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multisymptom assessment | |||

| Symptom distress scale (SDS)6 | 13 | Severity | 1-5 Likert-type scale, with 5 indicating the most distress |

| Memorial symptom assessment scale (MSAS)4 | 32 | Frequency, severity, distress | 1-4 Likert-type scale, with 4 indicating the highest rating |

| Rotterdam symptom checklist (RSC)5 | 38 | Severity and impairment | 4-point Likert-type scale (not at all, a little, quite a bit, very much) |

| Edmonton symptom assessment system (ESAS)2 | 10 | Severity | Visual analogue scale 0-100 or numeric rating scale 0-10 |

| M D Anderson symptom inventory (MDASI)3 | 19 | Severity and interference | Numeric rating scale 0-10 |

| Quality of life | |||

| Quality-of-life questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ-C30)7 | 30 | Severity, functional effect, global-health status | 4-point Likert-type scale (not at all, a little, quite a bit, very much) |

| Short form 36 (SF-36)9 | 36 | Eight domains, including pain, fatigue or energy, and psychological distress | 5-point Likert (all of the time to none of the time) |

| Functional assessment of cancer therapy (FACT)8 | Module-specific | Several domains including symptoms | 5-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much) |

Pain, depression, and fatigue are prevalent and debilitating symptoms in patients with cancer (figure 1). As many as 60% of patients receiving active cancer treatment report pain, and this estimate increases to 80% for patients with advanced cancer. Up to 50% of patients with cancer meet the criteria for psychological distress, including depression, during the course of their illness.10 As many as 75% of patients have cancer-related fatigue.11 Studies of cancer-related symptoms have several limitations. Symptoms are commonly assessed and treated as separate and mutually exclusive entities (eg, pain, fatigue, and depression). Physical symptoms (pain) are dissociated from cognitive symptoms and affective symptoms (anxiety and depression). Furthermore, symptoms are assessed and reported without stratifying for heterogeneity of disease type, treatment, and response to treatment.12 Studies of predictors of cancer-related symptoms have traditionally focused on disease-related variables (stage of disease), clinical health status (performance status, comorbid conditions), and sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, race, marital status), and have not included mechanism-based assessments. A report by the National Cancer Institute12 called for studies that will help understand the risks for pain, depression, and fatigue in people with cancer. One important gap is the investigation of multiple symptoms of cancer that might identify common biological mechanisms among cancer-related symptoms with imaging, molecular, and other innovative techniques. Advances in molecular technology now allow us to assess common genetic variations that may serve as stable markers of symptom severity, prognosis, and outcome in patients with cancer.

Basic principles of molecular epidemiology

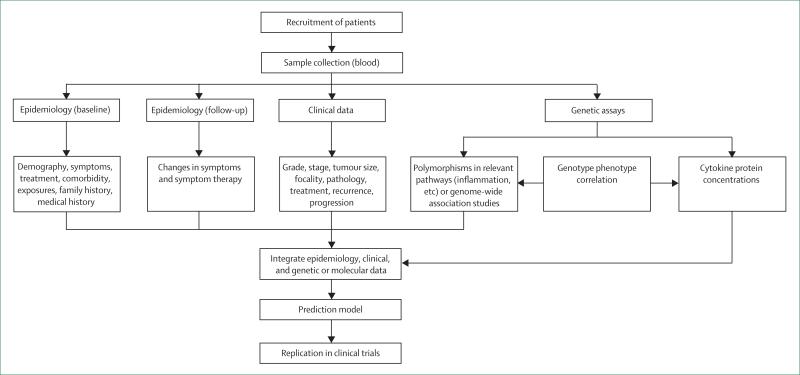

Neither genetics nor environment alone is responsible for producing individual variation. Molecular epidemiology provides the tools for understanding the extent of interaction between genetic and non-genetic factors in cancer-related symptoms. Whereas traditional epidemiological approaches have identified subgroups at higher risk for symptoms (by gender, age-group, and racial or ethnic groups), molecular epidemiology integrates the use of biological markers that measure events at the physiological, cellular, and molecular levels. Molecular epidemiology represents the confluence of sophisticated advances in molecular biology and field-tested epidemiological methods. Integrating the use of molecular epidemiology methods (figure 2), improves the understanding of biological mechanisms and improves assessments of individual and group risks by providing person-specific information (genetic profile). Such an approach also has potential for exploring individual variation in symptom expression.

Figure 2.

Molecular epidemiology approach to cancer-related symptoms

Genetic variation

The Human Genome Project and the HapMap Project provide a preliminary draft of human genetic variation. The most common form of DNA variation are differences in a single base pair (ie, single nucleotide polymorphisms [SNPs]), which occur about every 1000 bases in the genome of 3 billion base pairs. Many of these SNPs do not have an effect on function, whereas others may predispose individuals to disease or influence their response to drugs. There are also other less common genetic variations including duplications, insertions, deletions, copy number variations, rearrange ments, and transpositions.

SNPs that affect the function of the gene product, including those in the coding region, promoter, 3′ untranslated region (UTR), and 5′ UTR of the gene are typically investigated in genetic association studies. Computerised algorithms such as Polymorphism Pheno-typing (PolyPhen) and Sort Intolerant from Tolerant (SIFT) for predicting the functional effects of SNPs are used to prioritise SNPs for genetic-association studies in complex diseases. SNPs with minor allele frequency of more than 5% are good candidates for genetic association study of complex diseases because they are common in the population and thus yield better power to detect association with a complex disease.13–15

Adjacent SNPs on a single chromatid may be statistically and physically associated. A haploytpe, a combination of alleles at multiple linked loci that are transmitted together, can unambiguously identify all other polymorphic sites in its region. Thus, instead of searching for individual SNPs, investigators can focus on patterns of a few SNPs that define each haplotype. This information is valuable for investigating the genetics behind common diseases, and is collected by assessing the extent of linkage disequilibrium blocks in different ethnic or racial groups, as in the HapMap project. The identification of many SNPs in the human genome, coupled with advances in molecular technology and statistical methods, has enabled assessment of complex gene–environment and gene–gene interactions for cancer-related symptoms.

Studies in molecular and genetic epidemiology

Linkage studies

Linkage is the most effective approach to the identification of rare genetic variants with mendelian inheritance and high penetrance (expressed phenotype or trait). In linkage studies, the families are the sampling units and the analyses focus on familial inheritance patterns. The results of linkage studies can provide evidence for major gene effects on susceptibility to disease-related traits. The observations in a linkage study consist of the disease status and marker information of related individuals in families. Genetic linkage studies have been reported for pain16 and major depression disorder.17 However, there is limited information on genetic linkage studies of fatigue. The linkage methodology is not directly applicable for identifying genes of cancer-related symptoms because the phenotype is not well defined for other family members who do not have cancer.

Association studies: candidate-gene and genome-wide association

In contrast to linkage studies, association studies do not investigate familial inheritance patterns and are generally done in unrelated individuals. Both hypothesis-driven (candidate-gene, pathway-based) and hypothesis-generating (ie, genome-wide association) approaches have been used to identify genes for complex diseases.

Association studies of genetic polymorphisms and susceptibility to symptoms in patients with cancer have mostly used the candidate gene approach. In this hypothesis-driven approach, researchers use knowledge of polymorphisms and gene functions in the candidate gene, investigating one or a few selected polymorphisms at a time. These studies have yielded informative but conflicting results. Chanock and colleagues18 provide a comprehensive review of these limitations.

The recognition that complex diseases are multigenic and that polymorphisms in the same pathway might have a combined effect in the cause of complex diseases, led to the application of a pathway-based multigenic approach to association studies. Several studies of complex diseases such as cancer have shown the usefulness and encouraging results of this approach.19 However, although comprehensive, the pathway-based approach still relies on a-priori knowledge of SNPs and gene functions and on biological plausibility. Furthermore, there is concern about false-positive associations among the multiple comparisons being analysed. Although there has been a limited application of the pathway-based approach in the study of cancer-related symptoms, evidence suggests a role for the inflammation pathway in cancer and cancer-related symptoms,20–22 which might serve as a potential target for the study of the molecular mechanism for cancer-related symptoms.

Rapid advances in molecular and genetic technology coupled with the progress of the International HapMap Project have made genome-wide scanning approaches possible for understanding the molecular epidemiology of complex diseases. Whole-genome (genome-wide) scanning, hypothesis-free approaches allow for the examination of hundreds of thousands of SNPs at a time. With the inclusion of up to hundreds of thousands of SNPs in a single DNA chip, an increasing number of markers throughout the genome can be analysed efficiently. Although genome-wide association studies are effective for identifying genetic factors contributing to complex diseases (eg, obesity, diabetes), there has been little use of these approaches in research because of the cost and the need for very large samples sizes for replication studies. No genome-wide association studies of cancer-related symptoms have been reported.

Genotyping technologies

Rapidly emerging high-throughput technologies have made genotyping of large numbers of samples feasible and accurate. Genotyping typically includes the generation of allele-specific products for SNPs followed by their detection for genotype determination. Most genotyping technologies include the PCR amplification step of a desired SNP-containing region. PCR amplification is done at first to introduce specificity and increase the number of molecules for detection after allelic determination. Several robust genotyping platforms are available. High-density, whole-genome SNP array from Illumina or Affymetrix can query over 1 million SNPs on a single chip whereas custom designed SNP arrays can interrogate up to tens of thousands of SNPs simultaneously. Illumina's GoldenGate assay can assess 384–1536 SNPs together and 96 samples in parallel. Applied Biosystems’ SNPlex platform can assay up to 48 SNPs in one individual reaction and 384 samples on a single plate. Sequenom's iPLEX Gold assay can multiplex up to 40 SNPs and measure 384 samples together. Finally, Applied Biosystems’ Taqman assay is the gold-standard for genotyping individual SNPs. With four standard PCR machines, more than 6000 samples can be genotyped in an 8 h working day and may cost as little as US$0·01–0·10 per SNP, thus allowing for the clinical application of genotype profiling in large cohorts of patients.

Genetic-association studies of pain, depression and fatigue

Pleiotropy is the situation in which a given gene influences more than one trait. Pleiotropic actions of genes result in the genetic correlation of traits, because allelic variation in a gene will influence all traits in which that gene participates.16 Except for one study,23 genetic association studies of pain, depression, and fatigue in patients with cancer (table 2)24–28 have mainly focused on SNPs in genes involved in the pharmacokinetics and pharamcodynamics (ABCB1, OPRM1, CYP2D6) of opioids, the drug of choice for cancer pain.

Table 2.

Genetic association studies of pain, depression, and fatigue in patients with cancer

| Gene | Genotype | Population | Phenotype | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klepstad (2004)24 | COMT and opioid receptor, mu 1 (OPRM1) | OPRM1 -118A/G; -172 G/T, IVS2+31, IVS2+691 | 207 white patients admitted for cancer pain treatment | Morphine consumption and serum concentration | GG homozygotes need high morphine dose with high serum concentration |

| Rakvag (2005)25 | Catechol-O-Methyl-Transferase (COMT) | COMT 158 | 207 white patients with cancer receiving palliative care admitted for pain treatment | Morphine consumption | People with valine in protein need more morphine |

| Wang (2006)26 | Cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) | CYP2D*10 (100C→T inducing Pro34Ser) | 70 Chinese patients with gastric cancer admitted for gastrectomy | Tramadol consumption (2, 4, 24 and 48 h), pain visual analogue scale | Consumption of tramadol in group without CYP2D6*10 allele is higher than in other groups at 4, 24, and 48 h after surgery; no difference in pain intensity |

| Reyes-Gibby (2007)27 | COMT and opioid receptor, mu 1 (OPRM1) | COMT 158 and -118A/G | 207 white patients admitted for cancer pain treatment | Morphine consumption | People with valine allele need more morphine; those with COMT Met and OPRM1 A combination require lowest morphine for achieving pain relief |

| Campa (2007)28 | ATP-binding cassette B1 (ABCB1)) | ABCB13435C/T | 137 white patients with cancer, 77 of 137 had metastatic disease | Verbal rating scale (5-point Likert scale) and numeric rating scale (0-10) | Pain relief significantly associated with ABCB1; combination of C/C of ABCB1 and G/G of OPRM1 lowers response to morphine. |

| Reyes-Gibby (2007)23 | Tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF), interleukin 6 (IL6), and interleukin 8 (IL8) | TNF -308G/A; IL6 -174 G/C; IL8 -251T/A | 606 patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: 446 white, 125 African-American, and 35 Latin American | Numeric rating (0-10) of pain severity | Variation in IL8 -251T/A was a significant factor for severe pain for white patients |

Opioid pathway and cancer-related symptoms

As the most important target for morphine, polymorphisms of the mu opiod receptor gene, OPRM1, on human chromosome 6q24–q25 have been primary candidates for genetic influences on the efficacy of opioids.29 Klepstad and colleagues24 assessed the influence of the 118A→G OPRM1 polymorphism in a heterogeneous sample of Norwegian patients with cancer admitted for pain treatment. People who were homozygous for the variant G allele needed about twice the amount of morphine doses needed by patients homozygous for the A allele to achieve adequate pain relief (225 mg per day, 95% CI 136–313 vs 97 mg per day, 77–119; p<0·0001). The same group25 also assessed the influence of the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene, COMT, on chromosome 22q11.21 on opioid dose in the same samples of patients. The Val158Met polymorphism affects the activity catechol-O-methyltransferase. Patients with homozygous for valine (n=44) needed more morphine (155 mg per day [106–203]) than heterozygotes (n=96, 117 mg per day [97–137]) and methionine homozygotes (n=67, 95 mg per day [71–119]; p<0·0001).

In the same patients, Reyes-Gibby and colleagues assessed the potential joint effects of the COMT and OPRM1 gene variants in the clinical efficacy of morphine.27 Carriers of the OPRM1 AA and catechol-O-methyltransferase Met/Met genotypes required the lowest morphine dose to achieve pain relief (87 mg per day [95% CI 57–116]) and those with neither Met/Met nor AA genotype needed the highest morphine dose (147 mg per day, 100–180). The significant joint effects for the Met/Met and AA genotypes (odds ratio 0·278 [95% CI 0·102–0·756]; p<0·0001) persisted, even after controlling for demographic and clinical variables in the multivariable analyses.

Campa and colleagues28 also assessed the importance of the OPRM1 118A→G polymorphism on morphine pain relief in 137 patients with cancer of Italian origin. AA homozygotes had greater reduction in pain than GG homozygotes. They also assessed the 3435C→T SNP of ABCB1, a major determinant of morphine bioavailability, and found that TT homozygotes experienced significantly greater pain relief than homozygous wild-type CC carriers. The two genes also have a significant joint effect on morphine pain relief: patients homozygous for OPRM1 AA and ABCB1 TT had greater pain reduction (change in pain severity score=4·8, 95% CI 4·21–5·39, p<0·0001) compared with people homozygous for OPRM1 AA but with CC or CT genotypes of ABCB1 (3·1, 2·72–3·48) or with other allele combinations (1·3; 0·65–1·95).

These studies suggest that genetic factors play a part in determining patients’ responses to opioids. However, there has been limited investigation on genetic susceptibility to the development of pain, fatigue, and depressed mood in patients with cancer. Since there are few data on the influence of genetic polymorphism in the occurrence of these traits, and in view of the cost of genome-wide association studies, an effective approach to identify initial polymorphisms is the candidate gene approach in a defined pathway. In this approach, candidate genes are chosen on the basis of the known pathophysiology of the disease. Published research implicates cytokines in the biology of cancer, and converging lines of evidence from basic and clinical studies suggest cytokines as a common biological mechanism for severe and persistent symptoms and vulnerability to severe symptoms.

Epidemiological study of the molecular basis of cancer-related symptoms

Symptoms involve phases that can be described as symptom production (caused mainly by the cancer process, such as nociceptive input from bone metastases), symptom perception (which takes place at the level of the CNS), and symptom expression (influenced by the disease pathology but also by learned responses, sociocultural factors, etc).30 The type of cancer, stage of disease, location of tumour, and type and extent of therapy are also obvious factors to be considered in explaining the variability of symptom expression. The multiphase process of symptom production, perception, and expression provide several opportunities for risk factors, including genetic factors, to operate and interact.

Cytokines as potential markers for cancer-related symptoms

Originally proposed for epidemiological studies of cancer, the unifying premise of the integrative molecular epidemiology approach was that the same genes that are implicated in cancer risk might also be involved in the modulation of cancer outcomes.31 As an example of an integrative epidemiology concept, a recent study of patients with lung cancer patients showed that polymorphisms in cytokine genes, IL1A and IL1B, were important risk factors32 and a study of the same patients showed that cytokine genes were also important in the risk for pain severity.23 However, the strength of the associations between individual polymorphisms in cytokine genes and symptoms is not likely to be clinically applicable. We advance a hypothesis-driven pathway-based approach assessing polymorphisms in a panel of cytokine genes as potential markers for genetic susceptibility for cancer-related symptoms.

Cytokines and cancer

Cytokines are soluble proteins or glycoproteins that act as mediators of cell-to-cell communications and are integral to the function of immune cells. Cytokines are pleiotropic and their multiple overlapping functions depend on their local concentration, the type and the maturational stage of the responding cell, and the presence of other cytokines and their mediators. The roles of cytokines in the biology of various neoplastic disorders have been extensively studied. Cytokines are aberrantly produced by cancer cells, macrophages, and other phagocytic cells.33,34

Cytokines and pain

The classical view of pain-transmission suggests that when a painful stimulus is encountered, peripheral pain-responsive Aδ and C nerve fibres are excited. These axons relay action potentials to the spinal-cord dorsal horn. Neurotransmitters are then released by the sensory neuron and these chemicals bind to and activate postsynaptic receptors on pain-transmission neuron the cell bodies of which are in the dorsal horn. Axons of the pain-transmission neurons then ascend to the brain, carrying information about the painful event to higher centres. More recently, a non-classical view of pain has emerged, suggesting that proinflammatory cytokines released by activated glial cells in response to inflammation or other cytokines, nerve trauma, or both cause hyperexcitability in pain transmission neurons and exaggerated release of substance P and excitatory aminoacids from presynpatic terminals produces an exaggerated pain response.35 This view was later supported by studies showing that intrathecal administration of cytokine attenuated or increased pain.36 Cancer might also lead to activation of glia in CNS regions linked to the production of sickness response and able to produce proinflammatory cytokines. Studies also suggest that cytokines released during inflammation or tissue damage (as in the cancer process) modify the activity of nociceptors contributing to pain hyper sensitivity. Other studies suggest that chemokines might produce increased sensitivity to pain via direct actions on chemokine receptors expressed by nociceptive neurons.37

Cytokines and depression

Depression has been associated with increases in circulating concentrations of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin 6 in adults with major depression,38 and in people with depression associated with chronic medical disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis,39 cancer,40 and cardiovascular disease.41 Exaggerated activation of the inflammatory response following acute psychological stress, with greater increases of interleukin 6 and activation of nuclear factor κB, a transcription factor that signals the inflammatory cascade,42 has been observed. Anisman and colleagues43 reported increases in circulating concentrations of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) α and interleukin 1 in patients with depression including late-life depressive disorder. A large cohort of patients with depression also had high plasma concentrations of interleukin 12. Other studies of depressive disorders also suggest that serum TNFα is significantly higher in patients with depression than in people without depression.44 Irwin and Miller45 review the influence of cytokines in depression associated with cancer and cancer treatment and their potential for treatment.

Cytokines and fatigue

Fatigue in patients with cancer can be attributed to changes in cytokine concentrations caused by the disease or its treatment.46 In patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, high pretreatment concentrations of pro inflammatory cytokines are associated with fatigue, appetite loss, and poor performance status.34,47 Fatigued breast cancer survivors were distinguishable from non-fatigued survivors by statistically significant increases in ex-vivo monocyte production of interleukin 6 and TNFα after lipopolysaccharide stimulation, high plasma concentrations of interleukin-1 receptor α and soluble interleukin-6 receptor (CD126), decreased monocyte cell-surface interleukin-6 receptor, and decreased frequencies of activated T lymphocytes.48 In these patients, there was an inverse correlation between soluble and cell-surface interleukin-6 receptors, consistent with inflammation-mediated shedding of receptors, and in-vitro studies confirmed that proinflammatory cytokines induced such shedding. Other studies provide pre liminary evidence of the important role of cytokines in fatigue severity.49

Polymorphisms in candidate cytokine genes

Cytokine genes are highly polymorphic. Polymorphisms found in the regulatory regions, including promoters and UTRs, in many cases can affect in-vitro expression of the gene product. Cancer-related symptoms are complex traits and several genes with small effects are likely to influence vulnerability. The strength of the associations between individual polymorphisms and symptoms is not likely to be clinically applicable. In the most likely clinical application, a combination of multiple polymorphisms would be used as predictors of clinical outcomes comple mentary to known symptom-modulating factors.

The following cytokine genes and their polymorphisms are some of the prominent candidate markers relevant in the study of cancer-related symptoms on the basis of their known biological processes, reports in the literature, the type of SNPs (ie, non-synonymous, 3′UTR, 5′UTR, promoter regions; prediction of functionality based on in-silico approaches, such as SIFT, PolyPhen; and minor allele frequency greater than 5%.

Interleukin 1 participates in activating T cells and inducing the expression of adhesion molecules. The activity of this cytokine is determined by two distinct polypeptides, interleukin 1α and interleukin 1β, and a natural competitive inhibitor, interleukin-1-receptor antagonist (IL1RN). Interleukin 1α, interleukin 1β, and IL1RN are mapped to a closely linked gene cluster on chromosome 2q13–q21. Interleukin 1 has been implicated in pain response50 and might contribute to the variation in postoperative morphine consumption.51 Patients with Alzheimer's disease who are heterozygous for the IL1 –511C→T SNP are three times more likely to develop depressive symptoms than CC homo zygotes.52

Interleukin 2 is a key T-helper-1 cytokine and acts as a growth factor or activator for T cells, natural killer cells, and B cells. This cytokine promotes T-cell proliferation, enhances cytotoxicity, increases the secretion of inter-feron γ and other interleukins, and upregulates the expression of cell-adhesion molecules. IL2 is located on 4q26–q27. A –330T→G SNP in the IL2 promoter region is associated with increased production of interleukin 2.53 The cytokine has been implicated in complex regional pain syndrome54 and painful neuropathies.

Interleukin 4 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that also has proinflammatory activities. This cytokine is a growth factor for B cells and promotes IgE and IgG synthesis and is produced by T-helper-2 cells, CD4+ T cells, and mast cells. Recent data suggest that interleukin 4 might provide a significant immunomodulatory signal protecting against microglia-mediated neurotoxicity.55 This cytokine is associated with the presence of chronic widespread pain56 and painless neuropathies.57

Interleukin 6 is a proinflammatory cytokine released in response to infection, trauma, and neoplasia with key roles in immune and acute-phase response and haemopoiesis. In cancer, high concentrations of circulating interleukin 6 are seen in almost every type of tumour and predict a poor outcome.58 Interleukin 6 has a significant amount of pleiotropism and can modulate the effects of other cytokines, interact with glucocorticoids, and play a part in pain facilitation and enhancement. The –174G→C SNP in the IL6 promoter region leads to decreased production of the cytokine.59,60 GG homozygosity at IL6 –174 is associated with pain in patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.61

One of the major mediators of the inflammatory response, interleukin 8 is secreted by several cell types. Interleukin 8 is a chemical signal that attracts neutrophils at the site of inflammation and is therefore also known as neutrophil chemotactic factor; it is a potent angiogenic factor. IL8 is located on 4q13–q21. Clinical studies show that patients with chronic pain conditions, such back pain,62 postherpetic neuralgia,63 and unstable angina,64 have high concentrations of interleukin 8. A promoter SNP, IL8 –251T→A, affects concentrations of the cytokine.65 Recently, variation in this SNP was found to affect risk for pain severity among newly diagnosed, previously untreated patients with lung cancer.23

Also known as the human cytokine-synthesis inhibitory factor, interleukin 10 inhibits the production of T-helper-1 cells and macrophage function. The two major activities of interleukin 10 include inhibition of cytokine production by macrophages and inhibition of the accessory functions of macrophages during T-cell activation. The effects of these actions cause interleukin 10 to play mainly an anti-inflammatory part in the immune system. Three promoter SNPs have been widely studied: –1082A→G, –819C→T, and –592C→A. The presence of the –1082G allele is associated with increased production of interleukin 10. The–592C→A transversion results in increased promoter activity. Studies suggest that interleukin 10 is associated with pain and that it has a potential role in pain therapy.66

Interleukin 12 stimulates production of interferon γ and TNFα from T cells and natural killer cells, and decreases suppression of interferon γ by interleukin 4. Because interleukin 12 plays a central part in regulating both innate and adaptive immune responses, it might have potent anticancer effects and synergise with several other cytokines for increased immunoregulatory and antitumour activities. This interleukin has been associated with depression.67 An SNP at position 1188 in the 3′ untranslated region (1188A→C) of IL12B modulates gene expression.68

Interleukin 13 is implicated as a central mediator of the physiological changes induced by allergic inflammation in many tissues. This cytokine induces its effects through a receptor with multiple subunits that include the alpha chain of the interleukin 4 receptor. Interleukin 13 modulates hyperalgesia.69

A proinflammatory cytokine involved in the regulation of many biological processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, lipid metabolism, and coagulation, TNFα has been implicated in various diseases, including autoimmune diseases, insulin resistance, and cancer. The possible involvement of TNFα in neoplastic cachexia as well as the neuroprotective function of this cytokine and its important role in pain facilitation and enhancement has also been suggested.70,71 Genetic polymorphisms in the promoter region of TNF could modulate protein expression. The –308G→A transition in the promoter region results in increased expression of TNFα in vitro and in vivo.72

The only member of the type II class of interferons, interferon γ is a dimerised soluble cytokine. This interferon was originally called macrophage-activating factor and is the hallmark cytokine of T-helper-1 cells. Natural-killer cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells also produce interferon γ. Prolonged presence of high concentrations of interferon γ in the CNS might contribute to central sensitisation and persistent pain by reducing inhibitory tone in the dorsal horn.73,74 There seems to be an association between the AA homozygosity –874 A/A, which decreases production of interferon γ, and chronic fatigue syndrome has been suggested.75

Conclusion

Many patients continue to have severe and persistent symptoms even with targeted therapies. Large individual variations in the patients’ response to treatment had been explained as resulting from either disease-related variables (stage of disease), clinical health status (performance status, comorbid conditions), or sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, race, marital status). Advances in molecular technology now allow us to assess the extent to which host genetic variations affect the experience of cancer-related symptoms and response to interventions.

There is ample evidence that polymorphisms in cytokine genes play a part in cancer, and studies also suggest their associations with pain, depression, and fatigue. Applying an integrative approach to understanding the molecular epidemiology of cancer-related symptoms offers the opportunity of providing information on which specific genes could be used for identifying cancer patients that are likely to respond to cancer and symptom therapy. The importance of correlating the genotype status with the circulatory concentrations of the relevant cytokines, as well as those of the main neuroendocrine substances involved in the psycho-neuroendocrine modulation of cytokine network, namely opioid peptides, endocannabinoid agents and pineal indoles should also be considered. Significant opportunities exist for translational research strategies that focus on the management of cancer-related symptoms with new therapies targeting the cytokine pathways (such as the observed diminution in fatigue in patients treated with CNTO328, an interleukin-6 antibody, in clinical trials). Cytokine gene variants might be markers for severe and debilitating symptoms associated with cancer or its treatment. The long-term goal is to use this understanding of polymorphisms in cytokine genes and other genes to foster the development of targeted interventions that are the most effective and least toxic to patients living with cancer.

The future of genetic variation and cancer-related symptom research might need to move more toward a whole-genome association approach. Although cost and the need for large sample size may be challenging, recent major advances in genome-wide-association studies of cancer, cardiovascular diseases, obesity, and diabetes indicate a promising future for such an approach in identifying low-penetrance susceptibility loci of complex genetic traits.

For more on the Human Genome Project see www.genome.gov

For more on the HapMap Project see www.hapmap.org

Search strategy and selection criteria.

Data for this Review were identified by searches of Pubmed for articles published in the past 10 years with the search terms “pain”, “fatigue”, “depression”, “cancer”, “genes”, “polymorphisms”, “cytokines”, “epidemiology”. References were also identified from the reference lists of relevant articles. Only papers published in English were included.

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author is a recipient of KO7CA109043 from the National Institute of Health (NIH/NCI).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Reyes-Gibby CC, Aday LA, Anderson KO, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Pain, depression, and fatigue in community-dwelling adults with and without a history of cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:118–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton symptom assessment system (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson symptom inventory. Cancer. 2000;89:1634–46. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001001)89:7<1634::aid-cncr29>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. The memorial symptom assessment scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:1326–36. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Haes JC, van Knippenberg FC, Neijt JP. Measuring psychological and physical distress in cancer patients: structure and application of the Rotterdam symptom checklist. Br J Cancer. 1990;62:1034–38. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1990.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCorkle R, Young K. Development of a symptom distress scale. Cancer Nurs. 1978;1:373–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–76. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cella D. The functional assessment of cancer therapy-anemia (FACT-An) scale: a new tool for the assessment of outcomes in cancer anemia and fatigue. Semin Hematol. 1997;34(3 suppl 2):13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), I: Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miovic M, Block S. Psychiatric disorders in advanced cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:1665–76. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahlberg K, Ekman T, Gaston-Johansson F, Mock V. Assessment and management of cancer-related fatigue in adults. Lancet. 2003;362:640–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patrick DL, Ferketich SL, Frame PS, et al. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: symptom management in cancer: pain, depression, and fatigue, July 15–17, 2002. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;32:9–16. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/djg014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3812–14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramensky V, Bork P, Sunyaev S. Human non-synonymous SNPs: server and survey. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3894–900. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu Y, Spitz MR, Amos CI, Lin J, Schabath MB, Wu X. An evolutionary perspective on single-nucleotide polymorphism screening in molecular cancer epidemiology. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2251–57. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mogil JS. The genetic mediation of individual differences in sensitivity to pain and its inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7744–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levinson DF. The genetics of depression: a review. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chanock SJ, Manolio T, Boehnke M, et al. Replicating genotypephenotype associations. Nature. 2007;447:655–60. doi: 10.1038/447655a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu X, Gu J, Grossman HB, et al. Bladder cancer predisposition: a multigenic approach to DNA-repair and cell-cycle-control genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:464–79. doi: 10.1086/500848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reyes-Gibby CC, Spitz M, Wu X, et al. Cytokine genes and pain severity in lung cancer: exploring the influence of TNF-alpha-308 G/A IL6-174G/C and IL8-251T/A. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2745–51. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurzrock R. Cytokine deregulation in cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2001;55:543–47. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(01)00140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maier SF, Watkins LR. Immune-to-central nervous system communication and its role in modulating pain and cognition: implications for cancer and cancer treatment. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;12(suppl 1):S125–31. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reyes-Gibby CC, Spitz M, Wu X, et al. Cytokine genes and pain severity in lung cancer: exploring the Influence of TNF-alpha-308 G/A IL6-174G/C and IL8-251T/A. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2745–51. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klepstad P, Rakvag TT, Kaasa S, et al. The 118 A > G polymorphism in the human mu-opioid receptor gene may increase morphine requirements in patients with pain caused by malignant disease. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004;48:1232–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2004.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rakvag TT, Klepstad P, Baar C, et al. The Val158Met polymorphism of the human catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene may influence morphine requirements in cancer pain patients. Pain. 2005;116:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang G, Zhang H, He F, Fang X. Effect of the CYP2D6*10 C188T polymorphism on postoperative tramadol analgesia in a Chinese population. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:927–31. doi: 10.1007/s00228-006-0191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reyes-Gibby CC, Shete S, Rakvag T, et al. Exploring joint effects of genes and the clinical efficacy of morphine for cancer pain: OPRM1 and COMT gene. Pain. 2007;130:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campa D, Gioia A, Tomei A, Poli P, Barale R. Association of ABCB1/MDR1 and OPRM1 gene polymorphisms with morphine pain relief. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83:559–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang JB, Johnson PS, Persico AM, Hawkins AL, Griffin CA, Uhl GR. Human mu opiate receptor. cDNA and genomic clones, pharmacologic characterization and chromosomal assignment. FEBS Lett. 1994;338:217–22. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80368-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dalal S, Del FE, Bruera E. Symptom control in palliative care—Part I: oncology as a paradigmatic example. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:391–408. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spitz MR, Wu X, Mills G. Integrative epidemiology: from risk assessment to outcome prediction. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:267–75. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engels EA, Wu X, Gu J, Dong Q, Liu J, Spitz MR. Systematic evaluation of genetic variants in the inflammation pathway and risk of lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6520–27. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jin P, Panelli MC, Marincola FM, Wang E. Cytokine polymorphism and its possible impact on cancer. Immunol Res. 2004;30:181–90. doi: 10.1385/IR:30:2:181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurzrock R. Cytokine deregulation in cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2001;55:543–47. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(01)00140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maier SF, Watkins LR. Immune-to-central nervous system communication and its role in modulating pain and cognition: implications for cancer and cancer treatment. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17(suppl 1):S125–31. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milligan ED, Sloane EM, Langer SJ, et al. Controlling neuropathic pain by adeno-associated virus driven production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-10. Mol Pain. 2005;1:9. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oh SB, Tran PB, Gillard SE, Hurley RW, Hammond DL, Miller RJ. Chemokines and glycoprotein 120 produce pain hypersensitivity by directly exciting primary nociceptive neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5027–35. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05027.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zorrilla EP, Luborsky L, McKay JR, et al. The relationship of depression and stressors to immunological assays: a meta-analytic review. Brain Behav Immun. 2001;15:199–226. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2000.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zautra AJ, Yocum DC, Villanueva I, et al. Immune activation and depression in women with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:457–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Musselman DL, Miller AH, Porter MR, et al. Higher than normal plasma interleukin-6 concentrations in cancer patients with depression: preliminary findings. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1252–57. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Theroux P, Irwin M. The association between major depression and levels of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1, interleukin-6, and C-reactive protein in patients with recent acute coronary syndromes. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:271–77. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pace TW, Mletzko TC, Alagbe O, et al. Increased stress-induced inflammatory responses in male patients with major depression and increased early life stress. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1630–33. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anisman H, Ravindran AV, Griffiths J, Merali Z. Endocrine and cytokine correlates of major depression and dysthymia with typical or atypical features. Mol Psychiatry. 1999;4:182–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jun TY, Pae CU, Hoon H, et al. Possible association between G308A tumour necrosis factor-alpha gene polymorphism and major depressive disorder in the Korean population. Psychiatr Genet. 2003;13:179–81. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200309000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Irwin MR, Miller AH. Depressive disorders and immunity: 20 years of progress and discovery. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:374–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kurzrock R. The role of cytokines in cancer-related fatigue. Cancer. 2001;92(6 suppl):1684–88. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010915)92:6+<1684::aid-cncr1497>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rich T, Innominato PF, Boerner J, et al. Elevated serum cytokines correlated with altered behavior, serum cortisol rhythm, and dampened 24-hour rest-activity patterns in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1757–64. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Collado-Hidalgo A, Bower JE, Ganz PA, Cole SW, Irwin MR. Inflammatory biomarkers for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2759–66. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schubert C, Hong S, Natarajan L, Mills PJ, Dimsdale JE. The association between fatigue and inflammatory marker levels in cancer patients: a quantitative review. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:413–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Honore P, Wade CL, Zhong C, et al. Interleukin-1alphabeta gene-deficient mice show reduced nociceptive sensitivity in models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain but not post-operative pain. Behav Brain Res. 2006;167:355–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bessler H, Shavit Y, Mayburd E, Smirnov G, Beilin B. Postoperative pain, morphine consumption, and genetic polymorphism of IL-1beta and IL-1 receptor antagonist. Neurosci Lett. 2006;404:154–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCulley MC, Day IN, Holmes C. Association between interleukin 1-beta promoter (-511) polymorphism and depressive symptoms in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004;124:50–53. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.20086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoffmann SC, Stanley EM, Darrin CE, et al. Association of cytokine polymorphic inheritance and in vitro cytokine production in anti-CD3/CD28-stimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes 2. Transplantation. 2001;72:1444–50. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200110270-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Uceyler N, Eberle T, Rolke R, Birklein F, Sommer C. Differential expression patterns of cytokines in complex regional pain syndrome. Pain. 2007;132:195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao W, Xie W, Xiao Q, Beers DR, Appel SH. Protective effects of an anti-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-4, on motoneuron toxicity induced by activated microglia. J Neurochem. 2006;99:1176–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uceyler N, Valenza R, Stock M, Schedel R, Sprotte G, Sommer C. Reduced levels of antiinflammatory cytokines in patients with chronic widespread pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2656–64. doi: 10.1002/art.22026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Uceyler N, Rogausch JP, Toyka KV, Sommer C. Differential expression of cytokines in painful and painless neuropathies. Neurology. 2007;69:42–49. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000265062.92340.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hong DS, Angelo LS, Kurzrock R. Interleukin-6 and its receptor in cancer: implications for translational therapeutics. Cancer. 2007;110:1911–28. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fishman D, Faulds G, Jeffery R, et al. The effect of novel polymorphisms in the interleukin-6 (IL-6) gene on IL-6 transcription and plasma IL-6 levels, and an association with systemic-onset juvenile chronic arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1369–76. doi: 10.1172/JCI2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Terry CF, Loukaci V, Green FR. Cooperative influence of genetic polymorphisms on interleukin 6 transcriptional regulation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18138–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oen K, Malleson PN, Cabral DA, et al. Cytokine genotypes correlate with pain and radiologically defined joint damage in patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2005;44:1115–21. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brisby H, Olmarker K, Larsson K, Nutu M, Rydevik B. Proinflammatory cytokines in cerebrospinal fluid and serum in patients with disc herniation and sciatica. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:62–66. doi: 10.1007/s005860100306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kotani N, Kudo R, Sakurai Y, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid interleukin 8 concentrations and the subsequent development of postherpetic neuralgia. Am J Med. 2004;116:318–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhou RH, Shi Q, Gao HQ, Shen BJ. Changes in serum interleukin-8 and interleukin-12 levels in patients with ischemic heart disease in a Chinese population. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2001;8:30–32. doi: 10.5551/jat1994.8.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hull J, Thomson A, Kwiatkowski D. Association of respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis with the interleukin 8 gene region in UK families. Thorax. 2000;55:1023–27. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.12.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Milligan ED, Sloane EM, Langer SJ, et al. Repeated intrathecal injections of plasmid DNA encoding interleukin-10 produce prolonged reversal of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2006;126:294–308. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee KM, Kim YK. The role of IL-12 and TGF-beta1 in the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morahan G, Huang D, Wu M, et al. Association of IL12B promoter polymorphism with severity of atopic and non-atopic asthma in children. Lancet. 2002;360:455–59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saade NE, Nasr IW, Massaad CA, Safieh-Garabedian B, Jabbur SJ, Kanaan SA. Modulation of ultraviolet-induced hyperalgesia and cytokine upregulation by interleukins 10 and 13. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:1317–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Watkins LR, Maier SF. Immune regulation of central nervous system functions: from sickness responses to pathological pain. J Intern Med. 2005;257:139–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Maier SF, Watkins LR. Cytokines for psychologists: implications of bidirectional immune-to-brain communication for understanding behavior, mood, and cognition. Psychol Rev. 1998;105:83–107. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.105.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wilson AG, Symons JA, McDowell TL, McDevitt HO, Duff GW. Effects of a polymorphism in the human tumor necrosis factor alpha promoter on transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3195–99. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vikman KS, Siddall PJ, Duggan AW. Increased responsiveness of rat dorsal horn neurons in vivo following prolonged intrathecal exposure to interferon-gamma. Neuroscience. 2005;135:969–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vikman KS, Duggan AW, Siddall PJ. Interferon-gamma induced disruption of GABAergic inhibition in the spinal dorsal horn in vivo. Pain. 2007;133:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Carlo-Stella N, Badulli C, De SA, et al. A first study of cytokine genomic polymorphisms in CFS: positive association of TNF-857 and IFNgamma 874 rare alleles. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24:179–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]