Abstract

Methods for isobaric tagging of peptides, iTRAQ or TMT, are commonly used platforms in mass spectrometry based quantitative proteomics. These two methods are very often used to quantitate proteins in complex samples, e.g., serum/plasma or CSF supporting biomarker discovery studies. The success of these studies depends on multiple factors, including the accuracy of ratios of reporter ions reflecting quantitative changes of proteins. Because reporter ions are generated during peptide fragmentation, the differences of chemical structure of iTRAQ balance groups may have an effect on how efficiently these groups are fragmented and thus how differences in protein expression will be measured. Because 4-plex and 8-plex iTRAQ reagents do have different structures of balanced groups, it has been postulated that indeed differences in protein identification and quantitation exist between these two reagents. In this study we controlled the ratios of tagged samples and compared quantitation of proteins using 4-plex versus 8-plex reagents in the context of a highly complex sample of human plasma using ABSciex 4800 MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer and ProteinPilot 4.0 software. We observed that 8-plex tagging provides more consistent ratios than 4-plex without compromising protein identification, thus allowing investigation of eight experimental conditions in one analytical experiment.

Keywords: iTRAQ, isobaric tag, multiplexing, 4-plex, 8-plex, shotgun proteomics, MALDI-TOF/TOF

Introduction

One major goal of proteomic profiling is an accurate quantitation of proteins in samples with high complexity and high dynamic range of protein concentrations, such as body fluids (serum, plasma, CSF, etc). Because high confidence peptide/protein identification and at the same time high confidence quantitation is a highly challenging task, multiple analytical approaches have been developed based on separation of proteins in-gel (2DE DIGE) and/or gel-free platform utilizing various methods of metabolic or chemical labeling.1 Each quantitative platform, including isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ), has strengths and limitations that have been experimentally compared.2

iTRAQ was developed in the early 2000s to be applied for the multidimensional protein identification technology (MudPIT) approach in which proteins are fragmented with trypsin or other proteolytic enzyme and subsequently chemically labeled with isobaric tags. This platform became a central technology in modern proteomics research; it is being widely used in all areas of research with great utility.3−8 As much as this approach seems to be straightforward, many aspects of this proteomic platform add sources of variability, and these limit the confidence in the output of protein identification and quantitation. The variability is introduced in multiple steps of sample preparation, efficiency of chemical tagging, performance of instrumentation, and method of acquisition used, as well as software (algorithms) and thresholds defined for database searches. Importantly, 4-plex and 8-plex tags provide overlapping mass of reporter ions; however, their balance groups are different, which has been postulated to have an impact on yield of fragmentation in collision induced dissociation (CID) leading to bias in quantitation.

Nevertheless, iTRAQ-based quantitation is an attractive method in global proteomic quantitation. First, it can be used after processing of any sample, e.g., cell lysates and proteins obtained from organelles, and as such is not limited to only those systems that can accommodate incorporation of stable isotopes during cell culture. Second, iTRAQ accommodates multiplexing up to 8 conditions/samples. Third, software for protein identification and quantitation is fairly well developed and tested in numerous experimental settings.

Recently Pichler and co-workers found that peptide labeling with 4-plex tags yields higher identification rates compared to 8-plex tags.9 This conclusion is of concern since experimental designs using 8-plex allow a much greater level and ease of comparison. For example, a study of one control and seven experimental conditions can be performed in one 8-plex experiment but would require at least three 4-plex experiments (running the control and up to three experimental samples in each). This increases the amount of control sample needed, labor and supplies, and chromatography and mass spectrometry time and likely introduces a source of variability.

The goal of this study was to compare experimental ratios of highly complex samples tagged with 4-plex versus 8-plex reagents in controlled ratios. We used ProteinPilot 4.0 software for data analysis, which is associated with the ABSciex 4800 MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Ammonium phosphate, α-cyano-4-hydroxycinammic acid (CHCA), and trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) were from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). HPLC grade water and acetonitrile (MeCN; ACN) were from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Sample Processing

Human plasma samples were shipped on dry ice from University of California–San Diego (UCSD) to University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) and on arrival remained frozen. HIV was inactivated in all samples by addition of 10 μL of freshly prepared 10% Triton X-100 and 50 μL of a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich St. Louis, MO) per 1 mL of sample. After 30 min samples were aliquoted, and those unused were stored at −80 °C. A 250 μL portion from each sample was filtered using a 0.2 μm spin filter and immunodepleted using an IgY14 column (Sigma-Aldrich) to remove the following proteins: albumin, α1-antitrypsin, IgM, haptoglobin, fibrinogen, α1-acid glycoprotein, apolipoprotein A-I and A-III, apolipoprotein B, IgG, IgA, transferrin, α2-macroglobulin, and complement C3. Flow-through fractions containing unbound proteins were concentrated using a Vivaspin 15R (Sartorius, Aubagne, France). Protein concentration was determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA). A total of 400 μg of proteins was pooled, and then aliquots of 50 μg of proteins were used in order to perform the iTRAQ labeling.

Trypsin Digest and Sample Processing

A 50 μg sample of proteins was precipitated with ethanol, by adding 10 vol of cold ethanol (200 proof) to each sample, incubating for 3 h at −20 °C, and centrifuging at 13,000g for 15 min at 4 °C. Proteins pellets were washed with 1 mL of 70% ethanol and dried in a SpeedVac (Thermo Scientific). Subsequent solutions were provided by iTRAQ reagent kits (Applied Biosystem, Carlsbad, CA).

Dried proteins were solubilized with dissolution solution, and proteins were denaturated with 1 μL of denaturant reagent. Protein reduction with reducing reagent was performed for 1 h at 60 °C. According to the manufacturer protocol, samples used for iTRAQ 4-plex were alkylated with 84 mM iodoacetamide for 30 min at room temperature, whereas for iTRAQ 8-plex we used the cysteine blocking solution from the iTRAQ kit for 10 min at room temperature.

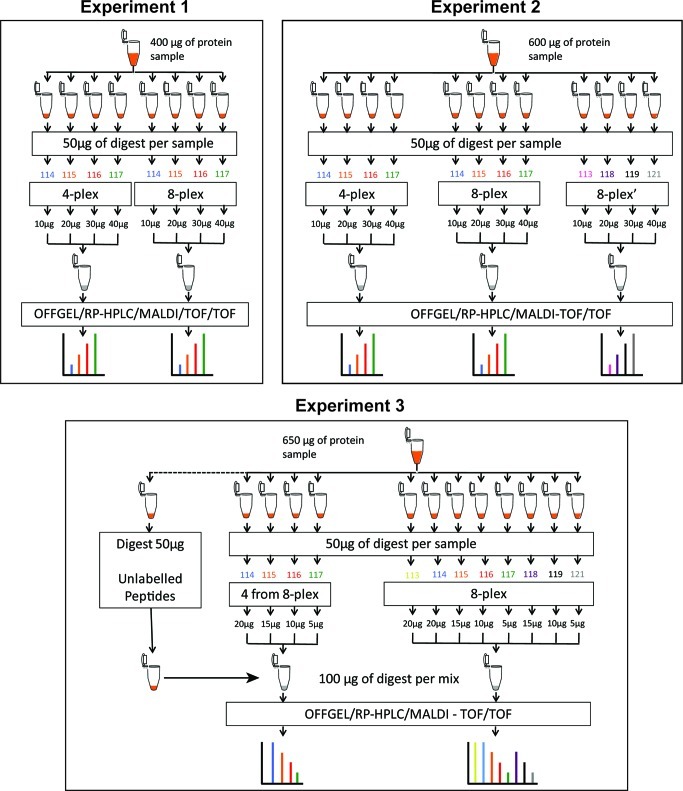

Samples were split and trypsin digested in parallel. Trypsin from ABI was reconstituted at 1 μg/μL with Milli-Q water, and 10 μg of trypsin was added to each sample. Digestion was performed for 16 h at 37 °C. After digestion, peptides were labeled with iTRAQ label reagent (ABI); 4-plex labeling was performed for 1 h at room temperature, and after the incubation the reaction was quenched with 100 μL of mQ water for 30 min at room temperature. The 8-plex labeling was performed for 2 h at room temperature. Labeled peptides were combined in one tube; we mixed a known quantity of peptides from each tag (see experimental design, Figure 1). Finally, pooled peptides were dried with the SpeedVac.

Figure 1.

Layout of experimental design. Samples used in all three experiments (400, 600 and 650 μg) were taken from the same larger pool of immunodepleted plasma samples (see Materials and Methods for details of immunodepletion). In all experiments regardless how much tagged peptides were used for analyses, 50 μg of peptide digest was always used for iTRAQ tagging to eliminate any effect of the tag to peptide ratio between experiments.

Samples were cleaned up using mixed cation exchange (MCX) column (Water Corp., Milford, MA). Labeled peptides were solubilized with 1 mL of 0.1% formic acid, passed through the column, and then the column was washed with 5% methanol, 0.1% formic acid solution, and then with HPLC grade methanol. Peptides were eluted with 1.4% NH4OH in methanol.

Samples were dried and reconstituted in 1.44 mL of 0.1% formic acid. Then, 360 μL of reconstituted sample was supplemented with 1.44 mL of OFFGEL solution. Next, samples were fractionated on the basis of their isoelectric point (pI) using 3100 OFFGEL Fractionator (Agilent, Inc. Santa Clara, CA). OFFGEL strips were rehydrated for 15 min at room temperature with 40 μL of OFFGEL solution. Peptide samples were loaded onto gel strips, splitting them equally between all 12 wells. Separation was performed for 20,000 V·h.

Collected fractions were cleaned with C-18 spin columns, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, fractions were adjusted to 5% acetonitrile (ACN) and 0.5% trifluoracetic acid (TFA) and passed through activated columns. Columns were washed twice with a 5% ACN, 0.5% TFA solution, and peptides were eluted with a 70% ACN, 0.1% TFA solution. Peptides were finally dried and stored at −80 °C until further use.

Off Line LC–MS/MS Analysis

Subsequent fractionation of OFFGEL fractions was performed off-line using Tempo LC system with automatic high density spotting onto MALDI target plates. Peptides were solubilized in 12 μL of 0.1% TFA, and 10 μL of samples were loaded onto a ProteoCol C18 trap cartridge (Michrom Biosources, Auburn, CA) and washed for 20 min at 9 μL/min. Gradient of separation was obtained using a ratio between two buffers: water/ACN/TFA (98:2:0.1) (Buffer A) and water/ACN/TFA (2:98:0.1) (Buffer B). To perform the separation, the subsequent gradient was applied by altering Buffer B percentage: time 0–5 min, 5% to 15%; 5–52 min, 15% to 35%; 52–54 min, 35% to 80%; 54–64 min, 80%; 64–65 min, 80% to 5%; and 65–72, min 5%. Peptide elution was monitored with a UV cell at 214 nm absorbance. After the UV cell, eluted peptides were mixed with a matrix solution (1.2 mg/mL in 75% ACN and 0.1% TFA solution) at a flow rate 1 μL/min using a Harvard Apparatus syringe pump. Fractions were spotted every 30 s, and the voltage applied to the plate during spotting was 2.8 kV.

Spotted fractions were submitted for data acquisition on a 4800 MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (ABI). MS spectra were acquired from 800 to 3000 m/z, for a total of 1000 laser shots by an Nd:YAG laser operating at 355 nm and 200 Hz. Laser intensity remains fixed for all the analyses. MS/MS analyses were performed using 2 kV collision energy with air as CID gas. Metastable ions were suppressed, for a total of 1000 laser shots.

Protein identification and quantification were performed with ProteinPilot 4.0 software using Paragon algorithm. The search parameters were as follows: iTRAQ 4-plex (peptide labeled), carbamidomethylation of cysteine, NCBI database (created on December 2011) restricted to Homo sapiens, iTRAQ 8-plex (peptide labeled), methylthioalkylation of cysteine, NCBI database (created on December 2011) restricted to Homo sapiens, for iTRAQ 4-plex and 8-plex, respectively.

Results

Our experimental design (Figure 1) used one large pool of human plasma immunodepleted of the 14 most abundant proteins. Regardless of how much of the resulting peptides was used to create final ratios, we always used 50 μg during the reaction for iTRAQ labeling. This approach eliminated potential variability that might be associated with efficiency of chemical labeling when ratios to tag and peptides are not uniform. After tagging, peptides were mixed in 1:2:3:4 ratios. In Experiment 1 we used 114, 115, 116, and 117 tags from 4-plex and from 8-plex kits and combined the following amount of labeled peptides (separately for the 4-plex and 8-plex) to achieve a 1:2:3:4 ratio from each kit: 10 μg (114), 20 μg (115), 30 μg (116), and 40 μg (117). In Experiment 2 we repeated these conditions and added a third sample in which the 113, 118, 119, and 121 tags from the 8-plex kit were used and peptides again mixed in a 1:2:3:4 ratio. However, in Experiment 3 we compared labeling of 114, 115, 116, and 117 tags from the 8-plex kit to labeling with all eight tags from the same 8-plex kit. Relative to the first two experiments, we scrambled tag assignment to the amount of peptides used, which allowed us to limit another potential bias (tag effect). In Experiment 3 we also added 50 μg of non-labeled peptides to the sample labeled with four tags to make up for the difference between amounts of peptides between those labeled with all eight tags. In all three experiments we used the same conditions for fractionation based on isoelectric point and subsequently RP-HPLC in TempoLC plate spotter. All data were processed by the same version of ProteinPilot with the same version of database.

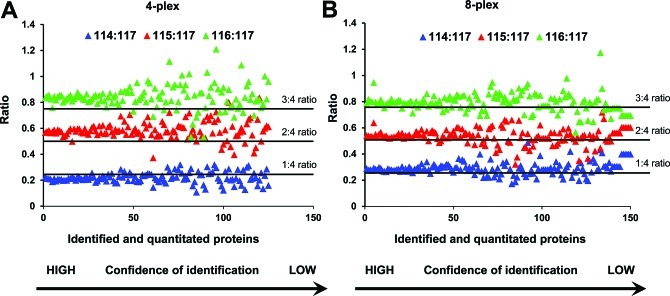

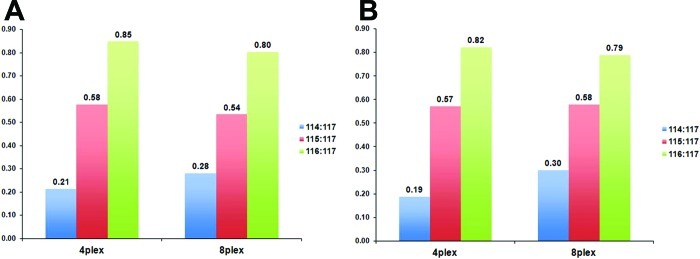

In Figure 2 we show the results derived from Experiment 1. All ratios were calculated relative to peptides tagged with 117 reporter ion. Ideally we should observe ratios of 0.25 (114:117), 0.5 (115:117), and 0.75 (116:117). Here we have made two observations. First, as confidence of protein identification decreases (plotted on the x-axis), the ratios for individual proteins (plotted on the y-axis) become more dispersed and the groups start to overlap. Second, when we used tags from the 4-plex kit, ratios of 114:117 showed lower than expected values, whereas when we used tags from the 8-plex kit the ratio of 114:117 was as expected (0.25). The two other ratios were very similar for both kits, and all were slightly higher than expected.

Figure 2.

Correlation between confidence of protein identification and ratios of iTRAQ reporter ions. Data presented in this figure are from Experiment 1 in Figure 1. Proteins were plotted by decreasing value of confidence of identification (x axis) and ratios that were calculated as relative to 117 reporter ion (y axis). (A) Plot for 114, 115, and 116 m/z reporter ions from iTRAQ 4-plex kit. (B) Ratios for the same m/z set of reporter ions from iTRAQ 8-plex kit.

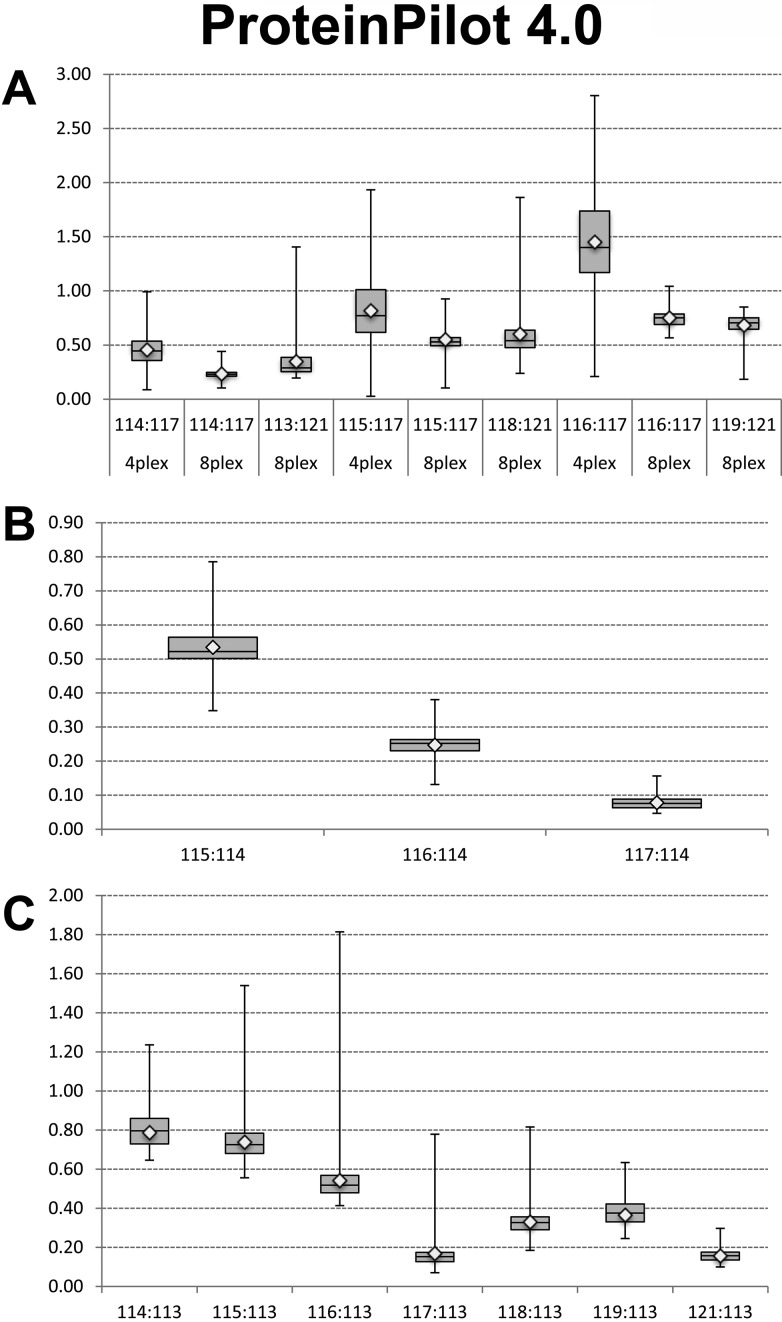

In Figure 3 we present a comprehensive comparison of ratios derived from all three experiments as a box-plot analysis. As shown in panel A, comparison of the ratios from Experiment 2 shows a greater dispersion of data when tags from the 4-plex kit were used. Comparison of the box (containing the values from 25% to 75% of the ratios) reveals that the tags from the 8-plex that have reporter masses similar to those of the 4-plex have a tighter distribution than those from the 4-plex. In panel B we present analysis of the spread of ratios for tags 115, 116, and 117 from the 8-plex kit relative to the 114 tag when labeled samples were mixed with an equal amount of non-labeled peptides. In this experiment measured ratios indicated that the presence of non-labeled peptides skewed results toward lower than expected values, which would have been 0.75 (115/114), 0.50 (116/114), and 0.25 (117/114), respectively. Dispersion of ratios was highest for 115/114 and lowest for 117/114. In panel C we show comparison of ratios from the second part of Experiment 3 in which we used all tags from the 8-plex kit; however, samples were mixed in 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, and 1:4 ratios and all were calculated as relative to the 113 tag. In this data set experimental ratios matched expected values for the following tags: 115/113 was 0.75, 116/113 was 0.5. Ratios for tags 117/113 and 121/113 were comparable to each other; however, both were below the 0.2 mark while we expected them to be at the 0.25 mark. Ratios of 118/113, 119/113, and 114/113 were skewed to lower values quite substantially in some instances. Besides the fact that higher ratios had a larger spread of values in the top and bottom quartiles, there was no obvious pattern of systematic skew of data in either the top or bottom quartiles across all comparisons.

Figure 3.

Box-plot of the ratios comparing effect of tags from iTRAQ 4-plex and 8 plex kits. Data presented are from Experiment 2 in panel A and from Experiment 3 in panels B and C. (A). Ratios were calculated as relative to the highest amount of peptides tagged with 117 for 4-plex and 8-plex and 121 for 8-plex only. Therefore, the first three box-plots represent a 1:4 ratio (expected value 0.25), the second three box-plots represent a 1:2 ratio (expected value 0.5), and the third set of box-plots represents a 3:4 ratio (expected value 0.75). (B). Box-plot analysis of ratios from tagging peptides with 114, 115, 116, and 117 tags from 8-plex kit and mixed with an equal amount (50 μg) of non-labeled peptides. Ratios were calculated relative to 114 iTRAQ tag. (C). Box-plot analysis of ratios of peptides tagged with all 8 tags from 8-plex kit. The amount of peptide digest was the same (100 μg) as in panel B.

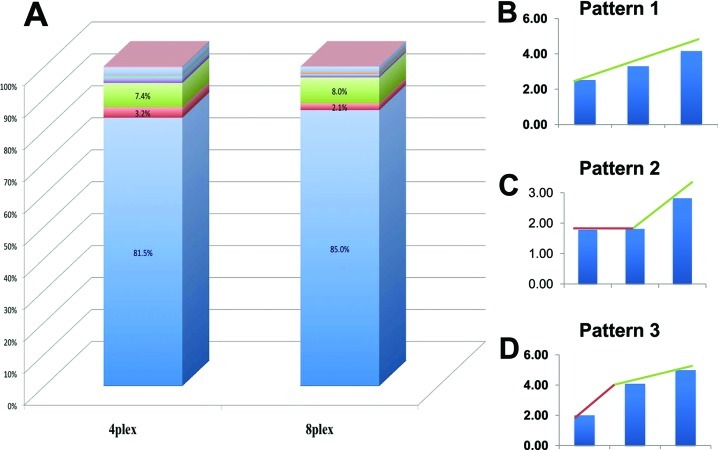

While manually analyzing ratios for individual peptides labeled with the different tags, we have found three predominant patterns of ratios regardless of whether the 4-plex or 8-plex assay was used (Figure 4B). Among them, linear dependence (pattern 1, Figure 4B) is the most desirable and expected and is representative of more than 80% of all patterns found (Figure 4A). More than 90% of peptides (Figure 4A) are included when these three patterns are combined. Although more than 80% of peptides showed linear ratios, we were interested in what impact the non-linear patterns have on the overall quantitative ratio of a protein and whether these non-linear patterns may skew quantitation. To investigate such possibility we selected two proteins: serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade G, member 1 precursor and hemopexin precursor. The peptides that contributed to the overall ratios of these two proteins contained a mixture of the three predominant peptide ratios as presented in Figure 4. Results of this analysis are presented in Figure 5 and indicate that despite having a mixture of all three patterns of peptide ratios, protein quantitation still shows linearity.

Figure 4.

Observed patterns of peptides’ ratios. Ideally, all peptides labeled with iTRAQ tags should show quantitative and linear ratios representing controlled mixing of protein samples. In reality, we have found seven non-linear or no change patterns representing less than 20% of the total number of peptides (A). Expected linear pattern is shown in panel B, and the two most predominant non-linear patterns are shown in panels C and D, respectively. When combined, these three patterns represent more than 90% of peptides. Data are based on Experiment 1 (Figure.1).

Figure 5.

Impact of non-linear peptide ratio on quantitative protein ratios. Two proteins, serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade G, member 1 precursor and hemopexin precursor, were selected for this comparison. Selection was based on the fact that in both cases overall protein ratios were calculated based on peptides representing a mixture of patterns 1, 2, and 3 shown in Figure 4. In both instances, Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade G, member 1 precursor (A) and hemopexin precursor (B) proteins showed overall linearity of ratios despite a mixture of linear and non-linear peptide ratios.

One point of interest that Pichler and co-workers found was that for samples labeled with iTRAQ 8-plex, the number of peptide-spectrum matches and unique peptides was more than 70% lower and the number of protein groups more than 60% lower, as compared to iTRAQ 4-plex.9 We identified 72 proteins with 99% and 98 with 66% confidence, respectively, using the 4-plex iTRAQ kit, and 64 and 90 proteins for the respective thresholds when we used the 8-plex iTRAQ kit. When we used a 50% confidence cutoff level, we found that samples labeled with 8-plex showed a decrease in identifications of only 13% at the peptide level and 19% at the protein level, and when compared to 4-plex these differences were not statistically significant. It is important to note that Pichler et al. performed their quantitation and identification using a LTQ Orbitrap and CID-HCD hybrid method and searches were performed using Mascot and Proteome Discoverer. We used MALDI 4800 with ProteinPilot 4.0 with Paragon Algorithm, which has an impact on the number of proteins identified.

Discussion

iTRAQ, as with any other analytical tool, is under continuous scrutiny by scientists looking for ways of most accurate measurements in quantitative proteomics.10−12 Because global profiling with quantitation is a multistep experiment, the final output may depend on wide range of factors ultimately contributing to skewed or even false positive results. One solution to prevent contribution of errors originating from iTRAQ data analyses is tightening thresholds; however, this approach must be used with caution because it may easily lead to loss of important information. Therefore, iTRAQ is being constantly evaluated and each study emphasizes different aspects of this approach. Gan and co-workers assessed the reliability of iTRAQ from perspective of different types of replicate analyses and took into account technical, experimental, and biological variations.2 Mahoney and co-workers reported that measured variability was a function of mean abundance, fold changes were biased toward the null, and variance of a fold change was a function of protein mass and abundance.10 Ow and co-workers13 evaluated the quantitative dynamic range of iTRAQ quantitation in high- and low-complexity samples. Although their study has similarities in experimental design, there are also important differences, including the use of non-mammalian samples to create a high complexity background, spiking in strategy to measure ratios, strong cation exchange (SCX) separation in first dimension, and a qTOF mass spectrometry platform. In a subsequent paper14 the authors used a similar strategy of spiking in known proteins to evaluate accuracy and precision of iTRAQ based quantitation and proposed spiking as a method to address accuracy and variance-stabilizing normalization to address the issue of precision.14 In another study evaluating accuracy of quantitation using iTRAQ ratios Thingholm and co-workers used whole HeLa cell lysate as a model sample and focused on phosphopeptides after enrichment on a TiO2 column.15 The authors used ESI as ionization mode and a LTQ XL Orbitrap as mass spectrometry platform. They reported correlation between reductions in identification efficiency with the size of the isobaric tag. Taking all these studies together, we have gained knowledge into understanding the iTRAQ platform; however, our study presented here offers insight from a different perspective. Here we perform a calculated experiment using immunodepleted human plasma, a body fluid that is highly complex and has a high dynamic range of protein concentration. Another way our study differs significantly is that we use a MALDI-TOF/TOF platform, followed by ProteinPilot 4.0 data analysis, both of which are offered from and supported by ABSciex, the manufacturers of iTRAQ. Other groups focused on software and mathematical models for iTRAQ data analyses and comparing algorithms across many platforms.16−19 Despite the collective effort, many outstanding questions related to accuracy and sources of variability in iTRAQ technique20 remain to be addressed, and more systematic studies with direct comparisons across mass spectrometry platforms, complexity of samples, and sample preparation methods are needed to fully understand bias resulting from iTRAQ quantitation.

We were intrigued by the report of Pichler and co-workers showing that peptide labeling with 4-plex tags yields higher identification rates compared to 8-plex tags.9 The authors used a LTQ Orbitrap mass spectrometer, CID-HCD hybrid method, and Proteome Discoverer Software (Thermo Scientific). The authors attributed the differences in yields to differences in chemical structures of balance groups and concluded that balance groups used in 8-plex tags are less susceptible to fragmentation. However on the basis of our previous experience we found not only that were the differences in peptide and protein identifications low but that the 8-plex tags resulted in increased confidence of quantitation with limited impact on protein identification. Taking this together we decided to test this effect using a systematic experimental approach to examine this as well as the accuracy of ratios obtained from intensities of the reporter ions with simplified experimental design to remove as much bias as possible. We intentionally chose human plasma because of our past work on biomarker discovery in body fluids (CSF, serum, and plasma analyses) and because it constitutes a highly complex mixture of proteins with high dynamic range of relative concentrations.21−28 Plasma/serum and CSF have been used in many biomarker discovery studies, including using iTRAQ platform; however, in many instances validation using larger population of clinical samples was disappointing, leaving questions about the sources of such disconnect unanswered. We used one large sample of immunodepleted plasma securing identical material for all experiments. Biological variability, although very important, was not an objective of our study, and pooling multiple samples averaged levels of proteins in the mix. Importantly, we used a MALDI-TOF/TOF 4800 mass spectrometer and ProteinPilot software with Paragon Algorithm, which are different than those used by Pichler and co-workers.9

We have found that 8-plex tags performed with higher quantitation accuracy than the same (by m/z of reporter ions) tags from 4-plex reagent, providing experimental ratios closer to theoretical ratios without dramatically affecting peptide or protein identification. Also, when confidence of protein identification decreases, the spread of ratios increases in both instances, however, to a lesser extent when 8-plex tags are used (Figure 3A). Therefore we conclude that more consistent ratios would be due to more complete CID fragmentation of tags using MALDI mass spectrometry. Box-plot analysis of ratios from subsequent experiments showed that spread of ratios is much tighter in two middle quartiles when 8-plex tags are used. Additionally, labeling peptides with 8-plex tags yielded more peptides with linear dependence of calculated iTRAQ ratios, thus better reflecting the ratio of controlled mixing.

Skewing of the measured ratios in the 1:1 mixture of tagged and nontagged peptides was an unexpected effect considering that the same amount of peptides tagged with 8-plex yielded ratios close to their theoretical values. In the mixture of tagged and nontagged peptides, for each peptide there were two different precursor ions that yielded identical or very similar fragmentation spectra. All spectra could contribute to confidence of protein identification; however, only half of the spectra contributed to quantitation. If peptide fragmentation used for protein identification and fragmentation of tags used for quantitation are processed by algorithm as separate events and results are merged at the final step, such effect should not be observed. On the other hand, if quantitation and identification is considered by algorithm as one event, 50% of spectra with null quantitation may induce a systematic skew in the calculation of ratios. Therefore, completeness of tagging may have a quite profound effect on quantitative output even if such incomplete tagging is proportional to all of the peptides in the sample. Also results from Experiment 1 may also suggest that ratio can be affected by either low level of precursor ion and thus more fragment ions were under background level and/or poor fragmentation during CID. We observed in other iTRAQ experiments examples in which the intensity of reporter ions was clearly above background providing good quantitation, but CID fragmentation of the tagged peptide was so poor that identification was calculated with confidence below 1% (data not shown).

Summarizing, we provide here experimental evidence that under our experimental conditions, 8-plex tagging is advantageous over 4-plex tagging in two aspects. First, 8-plex tagging provides more consistent ratios without compromising on protein identification. Second, the 8-plex system of tagging allows investigation of eight experimental conditions in one analytical experiment. A question that remains to be addressed is whether, during iTRAQ data acquisition, the peptide and reporter ion fragmentation that leads to identification and quantitation, respectively, should be considered as two separate events or dependent on each other. This would need to be addressed formally in subsequent experiments.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drs. Christie Hunter, Brian L. Williamson, and Sean Seymour from ABSciex, Inc. for critical comments. We would like to thank Ms. Robin Taylor for help in preparation of this manuscript. We thank Melinda Wojtkiewicz from the Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Core Facility at the University of Nebraska Medical Center for providing assistance with mass spectrometry analyses. This work was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health grants 5P01DA026146, 5R01DA030962, 2P30MH062261, and 5P20RR016469 and Nebraska Research Initiative.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

References

- Wu W. W.; Wang G.; Baek S. J.; Shen R. F. Comparative study of three proteomic quantitative methods, DIGE, cICAT, and iTRAQ, using 2D gel- or LC-MALDI TOF/TOF. J. Proteome Res. 2006, 5(3), 651–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan C. S.; Chong P. K.; Pham T. K.; Wright P. C. Technical, experimental, and biological variations in isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ). J. Proteome Res. 2007, 6(2), 821–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owiti J.; Grossmann J.; Gehrig P.; Dessimoz C.; Laloi C.; Hansen M. B.; Gruissem W.; Vanderschuren H. iTRAQ-based analysis of changes in the cassava root proteome reveals pathways associated with post-harvest physiological deterioration. Plant J. 2011, 67(1), 145–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao J. D.; Papavinasasundaram K. G.; Zheng X.; Chavez-Steenbock A.; Wang X.; Lee G. Q.; Av-Gay Y. Convergence of Ser/Thr and two-component signaling to coordinate expression of the dormancy regulon in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285(38), 29239–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manteca A.; Sanchez J.; Jung H. R.; Schwammle V.; Jensen O. N. Quantitative proteomics analysis of Streptomyces coelicolor development demonstrates that onset of secondary metabolism coincides with hypha differentiation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2010, 9(7), 1423–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivonen S. K.; Rokka A.; Ostling P.; Kohonen P.; Corthals G. L.; Kallioniemi O.; Perala M. Identification of miR-193b targets in breast cancer cells and systems biological analysis of their functional impact. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2011, 10(7), M110 005322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freue G. V.; Sasaki M.; Meredith A.; Gunther O. P.; Bergman A.; Takhar M.; Mui A.; Balshaw R. F.; Ng R. T.; Opushneva N.; Hollander Z.; Li G.; Borchers C. H.; Wilson-McManus J.; McManus B. M.; Keown P. A.; McMaster W. R. Proteomic signatures in plasma during early acute renal allograft rejection. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2010, 9(9), 1954–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. K.; Yates J. R. 3rd. Census for proteome quantification. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 2010, Chapter 13, Unit 13.12, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichler P.; Kocher T.; Holzmann J.; Mazanek M.; Taus T.; Ammerer G.; Mechtler K. Peptide labeling with isobaric tags yields higher identification rates using iTRAQ 4-plex compared to TMT 6-plex and iTRAQ 8-plex on LTQ Orbitrap. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82(15), 6549–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney D. W.; Therneau T. M.; Heppelmann C. J.; Higgins L.; Benson L. M.; Zenka R. M.; Jagtap P.; Nelsestuen G. L.; Bergen H. R.; Oberg A. L. Relative quantification: Characterization of bias, variability and fold changes in mass spectrometry data from iTRAQ-labeled peptides. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10(9), 4325–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly L.; Barnett M. H.; Zheng Y. Z.; Gulati T.; Prineas J. W.; Crossett B. Comprehensive tissue processing strategy for quantitative proteomics of formalin-fixed multiple sclerosis lesions. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10(10), 4855–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao J.; Damron F. H.; Basler M.; Digiandomenico A.; Sherman N. E.; Fox J. W.; Mekalanos J. J.; Goldberg J. B. Comparisons of two proteomic analyses of non-mucoid and mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates from a cystic fibrosis patient. Front. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ow S. Y.; Salim M.; Noirel J.; Evans C.; Rehman I.; Wright P. C. iTRAQ underestimation in simple and complex mixtures: “the good, the bad, and the ugly”. J. Proteome Res. 2009, 8(11), 5347–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karp N. A.; Huber W.; Sadowski P. G.; Charles P. D.; Hester S. V.; Lilley K. S. Addressing accuracy and precision issues in iTRAQ quantitation. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2010, 9(9), 1885–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thingholm T. E.; Palmisano G.; Kjeldsen F.; Larsen M. R. Undesirable charge-enhancement of isobaric tagged phosphopeptides leads to reduced identification efficiency. J. Proteome Res. 2010, 9(8), 4045–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onsongo G.; Stone M. D.; Van Riper S. K.; Chilton J.; Wu B.; Higgins L.; Lund T. C.; Carlis J. V.; Griffin T. J. LTQ-iQuant: A freely available software pipeline for automated and accurate protein quantification of isobaric tagged peptide data from LTQ instruments. Proteomics 2010, 10(19), 3533–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadforth I. P.; Dunkley T. P.; Lilley K. S.; Bessant C. i-Tracker: for quantitative proteomics using iTRAQ. BMC Genomics 2005, 6, 145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielow C.; Aiche S.; Andreotti S.; Reinert K. MSSimulator: Simulation of mass spectrometry data. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10(7), 2922–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arntzen M. O.; Koehler C. J.; Barsnes H.; Berven F. S.; Treumann A.; Thiede B. IsobariQ: software for isobaric quantitative proteomics using IPTL, iTRAQ, and TMT. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10(2), 913–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi M.; Anoop V.; Gleddie S.; Harris L. J. Proteomic profiling of two maize inbreds during early gibberella ear rot infection. Proteomics 2011, 11(18), 3675–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederin J. L.; Yu F.; Donahoe R. M.; Fox H. S.; Ciborowski P.; Gendelman H. E. Changes in the plasma proteome follows chronic opiate administration in simian immunodeficiency virus infected rhesus macaques. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012, 120, 105–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederin J. L.; Donahoe R. M.; Anderson J. R.; Yu F.; Fox H. S.; Gendelman H. E.; Ciborowski P. S. Plasma proteomic analysis of simian immunodeficiency virus infection of rhesus macaques. J. Proteome Res. 2010, 9(9), 4721–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciborowski P. Biomarkers of HIV-1-associated neurocognitive disorders: challenges of proteomic approaches. Biomarkers Med. 2009, 3(6), 771–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederin J.; Rozek W.; Duan F.; Ciborowski P. Biomarkers of HIV-1 associated dementia: proteomic investigation of sera. Proteome Sci. 2009, 7, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozek W.; Horning J.; Anderson J.; Ciborowski P. Sera proteomic biomarker profiling in HIV-1 infected subjects with cognitive impairment. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 2008, 2(10–11), 1498–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlautman J. D.; Rozek W.; Stetler R.; Mosley R. L.; Gendelman H. E.; Ciborowski P. Multidimensional protein fractionation using ProteomeLab PF 2D for profiling amyotrophic lateral sclerosis immunity: A preliminary report. Proteome Sci. 2008, 6, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laspiur J. P.; Anderson E. R.; Ciborowski P.; Wojna V.; Rozek W.; Duan F.; Mayo R.; Rodriguez E.; Plaud-Valentin M.; Rodriguez-Orengo J.; Gendelman H. E.; Melendez L. M. CSF proteomic fingerprints for HIV-associated cognitive impairment. J. Neuroimmunol. 2007, 192(1–2), 157–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozek W.; Ricardo-Dukelow M.; Holloway S.; Gendelman H. E.; Wojna V.; Melendez L. M.; Ciborowski P. Cerebrospinal fluid proteomic profiling of HIV-1-infected patients with cognitive impairment. J. Proteome Res. 2007, 6(11), 4189–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]