Abstract

A 6-year-old, intact, female miniature Doberman pinscher was evaluated for lethargy, intermittent back pain, and unstable gait. Physical and neurological findings included bradycardia, hypothermia, hyperesthesia, progressive and ascending ataxia, and proprioceptive deficits in all limbs. Laboratory findings and magnetic resonance imaging were consistent with disseminated granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis, confirmed later by microscopy.

A 6-year-old, intact, female miniature Doberman pinscher dog was presented to the referring veterinarian for lethargy and anorexia. The physical examination revealed that the temperature, pulse, and respiration were within normal limits and the only abnormality was the presence of pain on palpation of the lumbar spine. The tentative diagnosis was acute intervertebral disk disease, 2 wk of cage rest was recommended.

One week after the initial presentation, the dog was returned with a complaint of difficulty in walking. The physical examination revealed slight ataxia, decreased proprioception in the hind limbs, and continued pain when the thoracolumbar vertebrae were palpated. Radiography was recommended but declined by the owner. The veterinarian encouraged cage rest for 2 more weeks and offered pain medications, which were also refused. The dog was then taken to a veterinary chiropractor, which provided minor improvement.

Three days after the chiropractic treatment, the dog was referred to a 2nd veterinarian, as she was unstable when she walked and was now knuckling on all 4 limbs. The physical examination revealed that she was hypothermic (36.0°C) and bradycardic (56 beats per minute (bpm)). She walked with difficulty and now displayed forelimb proprioceptive deficits. She was no longer in pain when her spine was palpated; however, she was hyperesthetic.

Requests for a complete blood cell (CBC) count and serum biochemical profile were submitted. The results showed a mild thrombocytosis and decreased levels of amylase, urea, and creatinine (Table 1). An adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation test was conducted, and the result was within the normal range. Thoracic and abdominal radiographs were completed and considered normal. The dog was then referred to the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM).

Table 1.

Initial assessment at the WCVM revealed that the dog was in good body condition. The dog was depressed and minimally responsive. A physical examination confirmed hypothermia (35.4οC), bradycardia (66 bpm), and an arrhythmia (sinus arrest). A neurological examination indicated that all the cranial nerves were intact. The patellar reflexes were hypertonic and there were proprioceptive deficits in all 4 limbs. The dog would lie only in left lateral recumbency and would fall to her left side when she attempted to stand. Pain could not be elicited on palpation of the spine or on manipulation of the neck. The neuroanatomical diagnosis could not be localized to a single lesion.

The dog was mildly dehydrated and received 100 mL of lactated Ringer's solution, SC. A heating pad and several hot water bottles were placed in the dog's kennel to increase her body temperature. Her temperature rose to 38.2οC, but her mentation was deteriorating. An IV catheter was placed to provide direct venous access for maintaining her hydration status. She then received lactated Ringer's solution, IV, at 10 mL/h.

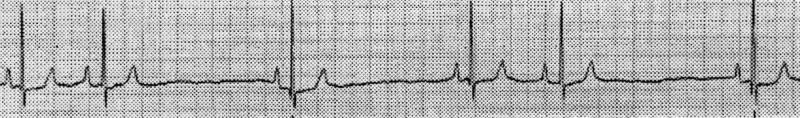

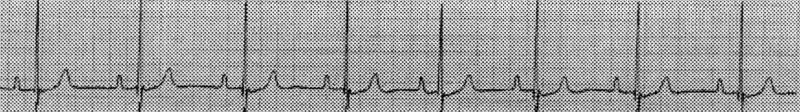

Measurement of serum thyroxine and thyroid stimulating hormone levels confirmed normal thyroid function. Electrocardiography was completed and revealed sinus arrest that was responsive to atropine, thereby suggesting sick sinus syndrome (Figures 1, 2).

Figure 1. Electrocardiogram at rest. Lead II rhythm strip, paper speed = 50 mm/s, 10 mm = 1 mV. Heart rate of 60 bpm and sinus arrest.

Figure 2. Electrocardiogram after 0.04 mg/kg bodyweight intravenous atropine. Lead II rhythm strip, paper speed = 50 mm/s, 10 mm = 1 mV. Heart rate increased to 90 bpm at a regular beat.

As the dog's condition was deteriorating, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and cervical spinal cord was conducted for interpretation of T-1 and T-2 weighted images taken in sagittal, dorsal, and transverse planes. There was an increased area of intensity in the brainstem and cranial cervical spinal cord on T-2 weighted images. There was an equivocal decrease in intensity of these same regions on T-1 weighted images. Contrast material (ProHance; Bracco Diagnostics, Mississauga, Ontario) was given (0.2 mL/kg bodyweight (BW)); however, enhancement was not detected. Disseminated granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis (GME) was tentatively diagnosed.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was collected from the lumbar region (L4–L5). Analysis of the CSF revealed a mononuclear pleocytosis consisting predominantly of lymphocytes with a few neutrophils and red blood cells. The protein content was also elevated. These analyses were most consistent with an inflammatory disease, such as GME. The dog was euthanized at the owners' request and the brain and spinal cord were examined using light microscopy.

The brain had numerous vessels surrounded by thick cuffs of epithelioid histiocytic cells and several lymphocytes. The cuffing was most prevalent within the white matter of the brainstem. Mononuclear infiltration of the meninges was mild and multifocal to locally extensive. The infiltration was more pronounced in the depths of the sulci. The brain and meningeal vessels were diffusely congested and occasionally hemorrhagic. The subarachnoid space in all sections of the spinal cord were markedly and diffusely infiltrated by massive numbers of epithelioid histiocytes and lymphocytes. Lymphocytes appeared to be more dominant immediately adjacent to the pia mater, whereas the histiocytes dominated more peripheral zones. These findings were compatible with a diagnosis of disseminated GME.

Granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis is a nonsuppurative inflammatory disease of the canine central nervous system (CNS), characterized by an accumulation of mononuclear cells in the parenchyma and meninges of the brain and spinal cord (1). It is the second most common inflammatory disease of the canine CNS, after canine distemper virus encephalitis (2). The etiological agent of GME is unknown. A T-cell mediated delayed type hypersensitivity of an organ-specific autoimmune disease is suspected (3,4,5). Dogs of any breed can be affected; however, female toy and small breed dogs tend to be at increased risk. It is often a disease of young to middle aged dogs (1 to 8 y), but it can occur at any age (1,2,5,6).

Granulomatous meningoencephalmyelitis can present in 3 different forms: ocular, focal, and disseminated. The ocular form is uncommon and is characterized by acute visual loss, dilated unresponsive pupils, and optic neuritis. It is the slowest to progress and may occur alone or accompanied by the focal or disseminated disease (1). The focal form presents as a granulomatous mass in the cerebral cortex, causing seizures. It manifests as a chronic and progressive disease (2). The disseminated form is rapidly progressive and has lesions distributed throughout the CNS. Clinical signs include neck pain, altered mentation, vestibular dysfunction, paralysis, and seizures (1,5,6).

Granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis is tentatively diagnosed based on history, clinical findings, and CSF analysis. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography (CT) are useful diagnostic tools to detect gross pathological lesions (4). A definitive diagnosis is confirmed at necropsy or by brain biopsy, using light microscopy.

Granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis is usually a progressive disease and the treatment is directed towards relieving clinical signs and inducing remission, rather than providing a cure. Immunosuppressive drugs, radiation therapy, or a combination of these is the recommended therapy (2). Survival times of up to 3 y have been reported; however, dogs with focal GME tend to survive longer than those with multifocal involvement. The prognosis for recovery of animals with disseminated GME is poor.

Dogs with GME usually have an abnormal CSF and its analysis frequently indicates a mononuclear pleocytosis and an increased protein content, as was seen in this case. Magnetic resonance imaging and CT are helpful in the diagnosis of many neoplastic and nonneoplastic brain disorders in animals (7). With regard to GME, MRI is preferred over CT, because it provides visualization of the brain without artifacts induced by the cranial bones, improved anatomic detail, and the ability to differentiate extravascular blood from surrounding structure (8). The MRI results from this case were characteristic of an inflammatory disease with areas of increased intensity on T-2 weighted images, and corresponding areas of decreased intensity on T-1 weighted images.

In this case, lesions were located in the brainstem and cervical spinal cord, and the dog displayed the characteristic clinical signs, such as altered mentation, back pain, hyperesthesia, ataxia, decreased conscious proprioception, exaggerated spinal reflexes, and eventual tetraparesis. Clinical signs were progressive over several weeks. The CBC count, chemical profile, CSF, MRI, and light microscopic findings were consistent with previous reports of disseminated GME (4,9,10). This case differed from those described in the literature by exhibiting hypothermia, bradycardia, and arrhythmia.

Bradycardia has only been reported in 1 case of focal GME in a 2-year-old, spayed female shih tzu; however, the etiology was not reported (11). In the case reported here, the bradycardia was likely due to sinus arrest, a primary disorder of the sinus node that temporarily impedes the generation of the cardiac impulses through surrounding tissue (12). This condition usually responds to atropine, as was seen in this case.

There are no documented cases of GME in which the dog was hypothermic. In contrast, most animals with GME have a fever (2,3). An acquired hypothalamic dysfunction secondary to an intracranial GME lesion may explain the hypothermia in this case (13).

This case illustrates an unusual clinical manifestation of GME.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Drs. David Fowler, Kim Tryon, Tanya Duke, Matt Thompson, and Bruce Grahn for their help with this case. CVJ

Dr. Fisher's current address is 517 Allen Drive, Delta, British Columbia V4M 3B9.

Margaret Fisher will receive an animalhealthcare.ca fleece vest courtesy of the CVMA.

References

- 1.Munana KR, Luttgen PJ. Prognostic factors for dogs with granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis: 42 cases (1982–1996). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998;212:1902–1906. [PubMed]

- 2.Fenner WR. Diseases of the brain. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, eds. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine. vol. 1. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1995:597–598.

- 3.Tipold A. Diagnosis of inflammatory and infectious diseases of the central nervous system in dogs: A retrospective study. J Vet Intern Med 1995;9:304–314. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.LeCouter RA, Grandy JL. Diseases of the spinal cord. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, eds. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine. vol. 1. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1995:608–657.

- 5.Kipar A, Baumgartner W, Vohl C, Gaedke K, Wellman M. Immunohistochemical characterization of inflammatory cells in brains of dogs with granulomatous meningoencephalitis. Vet Pathol 1998;35:43–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Sorjonen DC. Clinical and histopathological features of granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis in dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1990;26:141–147.

- 7.Thomas WB. Non-neoplastic disorders of the brain. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 1999;14(3):125–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Lobetti RG, Pearson J. Magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of focal granulomatous meningoencephalitis in two dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 1996;37:424–427.

- 9.Bailey CS, Higgins RJ. Characteristics of cerebrospinal fluid associated with canine granulomatous meningoencephalitis: a retrospective study. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1986;188:418–421. [PubMed]

- 10.Vandevelde M, Spane JS. Cerebrospinal fluid cytology in canine neurological disease. Am J Vet Res 1977;38:1827–1832. [PubMed]

- 11.Dzyman LA, Tidwell AS. Imaging diagnosis: granulomatous meningoencephalitis in a dog. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 1996;37: 428–430.

- 12.Carr AP, Tilley LP, Miller MS. Treatment of cardiac arrhythmias and conduction disturbances. In: Tilley LP, Goodwin J-K, eds. Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease: Manual of Canine and Feline Cardiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2001: 380–391.

- 13.MacKay BM, Curtis N. Adipsia and hypernatremia in a dog with focal hypothalamic granulomatous meningoencephalitis. Aus Vet J 1999;77:14–17. [DOI] [PubMed]