Abstract

Chronic anxiety is a common and debilitating result of traumatic brain injury (TBI) in humans. While little is known about the neural mechanisms of this disorder, inflammation resulting from activation of the brain's immune response to insult has been implicated in both human post-traumatic anxiety and in recently developed animal models. In this study, we used a lateral fluid percussion injury (LFPI) model of TBI in the rat and examined freezing behavior as a measure of post-traumatic anxiety. We found that LFPI produced anxiety-like freezing behavior accompanied by increased reactive gliosis (reflecting neuroimmune inflammatory responses) in key brain structures associated with anxiety: the amygdala, insula, and hippocampus. Acute peri-injury administration of ibudilast (MN166), a glial cell activation inhibitor, suppressed both reactive gliosis and freezing behavior, and continued neuroprotective effects were apparent several months post-injury. These results support the conclusion that inflammation produced by neuroimmune responses to TBI play a role in post-traumatic anxiety, and that acute suppression of injury-induced glial cell activation may have promise for the prevention of post-traumatic anxiety in humans.

Key words: lateral fluid percussion injury, neuroinflammation, post-traumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

The long-term consequences of traumatic brain injury (TBI) include a heightened risk of neuropsychiatric disorders, of which anxiety disorders are the most prevalent (Moore et al., 2006; Rao and Lyketsos, 2000; Vaishnavi et al., 2009). Studies of the etiology of anxiety disorders implicate exaggerated responses of the amygdala and insula (Carlson et al., 2011; Rauch et al., 1997; Shin and Liberzon, 2010; Simmons et al., 2006; Stein et al., 2007), impaired inhibition of the medial prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate (Davidson, 2002; Milad et al., 2009; Shin and Liberzon, 2010; Shin et al., 2006), and decreased hippocampal volume (Bremner et al., 1995; Sapolsky, 2000; Shin et al., 2006). Yet, whether and how TBI induces neurochemical, structural, and functional abnormalities in these structures is poorly understood.

There is increasing evidence that excessive inflammatory actions of the neuroimmune system may contribute to the development of anxiety disorders following TBI (Gasque et al., 2000; Hoge et al., 2009; Shiozaki et al., 2005; Spivak et al., 1997; Tucker et al., 2004; von Känel et al., 2007). Microglial cells are the first line of defense and primary immune effector cells in the central nervous system (CNS), and respond immediately to even small pathological changes from damaged cells, producing proinflammatory cytokines and toxic molecules that compromise neuronal survival (Aloisi, 2001; Gehrmann, 1996; Gonzalez-Scarano and Baltuch, 1999; Town et al., 2005). This rapid microglial response often precedes the more delayed, yet prolonged activation of astrocytes, and is thought to be involved with the onset and maintenance of astrogliosis (Graeber and Kreutzberg, 1988; Hanisch, 2002; Herber et al., 2006; Iravani et al., 2005; McCann et al., 1996; Zhang et al., 2010). It is well established that microglia and astrocytes are activated during the innate immune response to brain injury, leading to the expression of high levels of proinflammatory cytokines, most notably interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). While glial activation is typically neuroprotective (Aloisi, 2001; Farina et al., 2007), the chronic inflammatory responses and exaggerated proinflammatory cytokine levels observed following injury initiate neurotoxic processes resulting in secondary tissue damage (Gasque et al., 2000; Hailer, 2008; Lehnardt, 2010; Simi et al., 2007), neuronal death (Beattie et al., 2010; Brown and Bal-Price, 2003; Schmidt et al., 2005; Sternberg, 1997), secondary injury cascades (Ansari et al., 2008a,2008b; Bains and Shaw, 1997; Cernak et al., 2001b,2001a), and neuronal hyperexcitability (Beattie et al., 2010; Hailer, 2008; Riazi et al., 2008; Rodgers et al., 2009), all of which may contribute to the dysfunction of brain regions associated with anxiety.

Recently developed animal models of post-traumatic anxiety (Baratz et al., 2010; Fromm et al., 2004; O'Connor et al., 2003; Jones et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2010; Sönmez et al., 2007; Vink et al., 2003; Wagner et al., 2007) permit examination of the possible contributions of brain inflammation. Tests of post-traumatic anxiety in these models have typically included standard measurements of exploratory preference in mildly stressful environments, such as an open-field or elevated-plus testing apparatus. However, it has been frequently noted that measures of exploratory preference may be confounded by a marked overall decrease in exploration in brain-injured animals (Fromm et al., 2004; O'Connor et al., 2003; Vink et al., 2003). Decreased exploration cannot be attributed to TBI-induced motor deficits since numerous studies report only transient (∼ 1 week) deficits following trauma (Baratz et al., 2010; Bouilleret et al., 2009; Cutler et al., 2005,2006a,2006b; Dixon et al., 1996; Fassbender et al., 2000; Frey et al., 2009; Goss et al., 2003; Kline et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2010; Taupin et al., 1993; Wagner et al., 2007; Yan et al., 1992). Rather, TBI-induced decreases in exploration have been attributed to the indirect effects of freezing (a primary component of the rodent's natural defensive behavior repertoire; Blanchard and Blanchard, 1988), suggesting an abnormally heightened response to stress in brain-injured rats (O'Connor et al., 2003; Fromm et al., 2004; Vink et al., 2003).

Based on these results, we tested the hypothesis that trauma-induced innate immune responses contribute to the development of anxiety-like behaviors in rats by directly examining freezing responses to a minor (novel environment), and major (foot-shock) stressor, following lateral fluid percussion injury (LFPI; a clinically-relevant animal model of human closed-head injury). We also tested the effectiveness of a glial cell activation inhibitor, ibudilast (MN166), in attenuating post-injury freezing behavior and reducing reactive gliosis in brain regions associated with hyperexcitability in anxiety disorders.

Methods

Sixty adult virus-free male Sprague-Dawley rats (275–325 g; Harlan Laboratories, Madison, WI) were housed in pairs in temperature-controlled (23±3°C) and light-controlled (12-h:12-h light:dark cycle) rooms with ad libitum access to food and water. All procedures were performed in accordance with the University of Colorado Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines for the humane use of laboratory rats in biological research. The rats were randomly assigned to 1 of 10 groups (n=6/group). Six groups (surgically-naïve, sham-operated, sham-operated + vehicle, sham-operated + MN166, LFPI + vehicle, and LFPI + MN166) were shocked immediately after behavioral testing at 1 month post-surgery (sham surgery or LFPI in the experimental rats). Surgically-naïve rats received no injections or surgery, whereas sham-operated rats received surgery but were not injected. The final four groups received sham or LFPI surgery and either vehicle injections or MN166 treatment. Another four groups (sham-operated + vehicle, sham-operated + MN166, LFPI + vehicle, and LFPI + MN166) were run separately in a sucrose preference test to assess anhedonia (the inability to experience pleasure, a core symptom of human depression), without exposure to stressors (anxiety tests and foot shock).

Lateral fluid percussion injury

LFPI rats were anesthetized with halothane (4% induction, 2.0–2.5% maintenance) and mounted in a stereotaxic frame. The LFPI used in this study has been described previously (Frey et al., 2009; McIntosh et al., 1989; Thompson et al., 2005). A PV820 Pneumatic PicoPump (World Precision Instruments, Inc., Sarasota, FL) was used to deliver standardized pressure pulses of air to a standing column of fluid. A 3.0-mm-diameter craniotomy was centered 3 mm caudal to the bregma and 4.0 mm lateral to the sagittal suture, with the exposed dura remaining intact. A female Luer-Lok hub (inside diameter 3.5 mm) was secured over the craniotomy with cyanoacrylate adhesive. Following hub placement, the animal was removed from the stereotaxic frame and connected to the LFPI apparatus. The LFPI apparatus delivered a moderate impact force (2.0 atmospheres; 10 msec). The injury cap was then removed, the scalp was sutured, and the rats were returned to their home cages for recovery. Sham-operated rats underwent identical surgical preparation, but did not receive the brain injury.

Ibudilast (MN166) administration

MN166 (MediciNova Inc., San Diego, CA) is a relatively non-selective phosphodiesterase inhibitor with anti-inflammatory actions via glial cell attenuation, which has been found to reduce glia-induced neuronal death through the suppression of nitric oxide, reactive oxygen species, and proinflammatory mediators (Mizuno et al., 2004; Rolan et al., 2009). Treated rats received a 5-day dosing regimen of once-daily MN166 injections (10 mg/kg, 1 mL/kg subcutaneously in corn oil) 24 h prior to LFPI, the day of surgery and LFPI, and 3 days following LFPI. Weight was recorded prior to each dosing, and treatment was administered at the same time each day to maintain constant levels across a 24-h period. Dose selection was based on prior animal pharmacology results (Ledeboer et al., 2007), demonstrating MN166 to be safe and well tolerated, yielding plasma concentration-time profiles commensurate with high-dose regimens in clinical development. MN166 administered using this regimen yields plasma and CNS concentrations that are linked to molecular target actions, including most potently, macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) inhibition (Cho et al., 2010), and secondarily, phosphodiesterase (PDE)-4 and PDE-10 inhibition (Gibson et al., 2006). The relevance of MIF inhibition in disorders of neuroimmune function such as neuropathic pain has recently been well demonstrated (Wang et al., 2011). Such dosing regimens have clearly been linked to glial attenuation in other animal models (Ledeboer et al., 2007), and the anti-inflammatory actions of MN166 have recently been shown to suppress cerebral aneurysms in a dose-dependent manner (Yagi et al., 2010).

Tests of motor, vestibular, and locomotive performance

Baseline testing of motor, vestibular, and locomotive performance in all groups was conducted immediately prior to surgery, and again following a 1-week recovery period. These tests included ipsilateral and contralateral assessment of forelimb and hindlimb use to assess motor function, locomotion, limb use, and limb preference (Bland et al., 2000,2001), toe spread to assess gross motor response (Nitz et al., 1986), placing to assess visual and vestibular function (Schallert et al., 2000; Woodlee et al., 2005), a catalepsy rod test to assess postural support and mobility (Sanberg et al., 1988), bracing to assess postural stability and catalepsy (Morrissey et al., 1989;Schallert et al., 1979), and air righting to assess dynamic vestibular function (Pellis et al., 1991a,1991b). Scoring ranged from 0 (severely impaired) to 5 (normal strength and function). The individual test scores were summed and a composite neuromotor score (0–45) was then generated for each animal. In addition to the composite neuromotor score, limb-use asymmetry was assessed during spontaneous exploration in the cylinder task, a common measure of motor forelimb function following CNS injury in rats (Schallert et al., 2000,2006), and post-injury locomotor activity was assessed through distance traveled on a running wheel. Both tasks were scored for 5 min under red light (∼ 90 lux).

Behavioral measures

A novel environment was used to assess freezing behavior in response to a minor stressor (Dellu et al., 1996). The environment consisted of a standard rat cage with one vertically-striped and one horizontally-striped wall. No aversive stimuli were introduced in this context and no conditioning occurred. The rats were tested (5 min), and the percent of freezing behavior was assessed. Freezing was defined as the absence of movement except for heartbeat/respiration, and was recorded in 10-sec intervals.

Freezing behavior in the novel environment was measured before and after administration of a foot shock in a separate shock apparatus. The shock apparatus consisted of two chambers placed inside sound-attenuating chests. The floor of each chamber consisted of 18 stainless steel rods (4 mm diameter), spaced 1.5 cm center-to-center and wired to a shock generator and scrambler (Colbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA). An automated program delivered a 2-sec/1.5-mA electric shock. The rats were transported in black buckets and shocked immediately upon entry to the chambers. Following shock, the rats were returned to their home cages.

A sucrose preference test was also performed in separate groups of rats that did not receive foot shock or testing in the novel environment. This task is commonly used to measure anhedonia in rodent models of depression (Monleon et al., 1995; Willner, 1997). The sucrose preference task was included because anxiety and depression share high rates of co-morbidity in humans (Moore et al., 2006), and was assessed as a possible confound to freezing behavior, due to possible co-occurrence of depression-like behavior. The rats were first habituated to sucrose solution, and were tested during the dark phase of the light/dark cycle to avoid the food and water deprivation necessary when testing during the light phase. Day 1 and day 2 consisted of habituation, day 3 and day 4 were baseline (averaged), and day 5 was the first test day. The rats were presented with two pre-weighed bottles containing 2% sucrose solution or tap water for a period of 4 h. Thirty minutes into the task the bottles were swapped to force preference and counter for placement effects. Total sucrose intake and sucrose preference, calculate by: (sucrose intake/(sucrose intake + water intake * 100), were measured.

Timeline for behavioral testing

Following a 2-week recovery period from sham operation or LFPI in experimental animals, all groups except those to be evaluated for sucrose preference were tested in the novel context. Testing was performed at 2 weeks, and 1, 2, and 3 months post-surgery. Shock was delivered after behavioral testing was completed at the 1-month time point. Tests for sucrose preference were performed at 2 weeks, 1 month, and 3 months post-surgery, with no intervening foot shock.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunoreactivity for OX-42 (targets CD11b/c, a marker of microglial activation), and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; a marker of astrocyte activation) were measured using an avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase (ABC) reaction (Loram et al., 2009). Brain sections (12 μm) were cut on a cryostat and mounted onto poly-L-lysine-coated slides and stored at −80°C. Sections were post-fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min at room temperature, then treated with 0.03% H2O2 for 30 min at room temperature. The sections were incubated at 4°C overnight in either mouse anti-rat OX-42 (1:100; BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Jose, CA), or mouse anti-pig GFAP (1:100; MP Biomedicals, Aurora, OH). The next day, the sections were incubated at room temperature for 2 h with biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). The sections were washed and incubated for 2 h at room temperature in ABC (1:400; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and reacted with 3′,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Glucose oxidase and β-D-glucose were used to generate hydrogen peroxide. Nickelous ammonium sulfate was added to the DAB solution to optimize the reaction product. The sections were air-dried overnight and then dehydrated with graded alcohols, cleared in Histo-Clear, and cover-slipped with Permount (Fisher Scientific, Fairlawn, NJ). Densitometric analysis was performed using Scion Image software.

Image analysis

The slides were viewed with an Olympus BX-61 microscope, using Olympus Microsuite software (Olympus America, Melville, NY), with bright-field illumination at 10×magnification. The images were opened in ImageJ, converted into gray scale, and rescaled from inches to pixels. Background areas were chosen in the white matter or in cell-poor areas close to the region of interest (ROI). The number of pixels and the average pixel values above the set background were then computed and multiplied, giving an integrated densitometric measure (integrated gray level). Four measurements were made for each ROI; the measurements were then averaged to obtain a single integrated density value per rat, per region. All measurements were taken while blind to treatment group.

Statistical analyses

Results are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM). Analyses for all behavioral variables used analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures (time after injury), and treatment as the independent variable. The integrated density from the histology was only conducted at one time point, and utilized one-way ANOVAs to compare regions between groups. Data were analyzed using SPSS software, and in all cases statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Neuromotor composite scores of the brain-injured groups (LFPI + MN166 and LFPI + vehicle) did not significantly differ from controls [F(3,20)=0.803, p=0.508]. Rats in all groups consistently received normal scores on forelimb and hindlimb use, toe spread, placing, catalepsy rod, bracing, and air righting tests, indicating no impairments in motor, vestibular, or locomotive functioning due to TBI. There were also no significant between-group differences in limb-use asymmetry observed for contralateral [F(5,29)=0.544, p=0.741] and ipsilateral [F(5,29)=0.428, p=0.826] forelimb use during vertical exploratory behavior in the cylinder task, indicating no limb-use bias due to injury (Fig. 1A). No significant between-group differences were found in locomotor performance as evidenced by distance traveled during the running wheel activity [F(5,29)=0.069, p=0.996], revealing no post-injury impairments in locomotion (Fig. 1B). There were no significant between-group differences in the sucrose preference task [F(3,21)=0.338, p=0.798], indicating no impairments in hedonic states post-injury.

FIG. 1.

Cylinder task and running wheel activity at 1 week post-injury. (A) For LFPI rats, the mean number of spontaneous forelimb placements (ipsilateral and contralateral) during exploratory activity in the cylinder test did not differ from controls at 1 week post-injury. A reduction was seen in contralateral limb use in injured rats, but this reduction did not reach significance (p=0.741). (B) For LFPI rats, the mean change in distance traveled in the running wheel did not significantly differ from controls at 1 week post-injury. Data represent mean±standard error of the mean (LFPI, lateral fluid percussion injury).

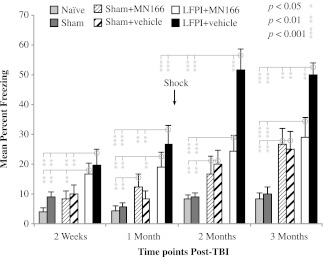

Despite normal motor, vestibular, and locomotive function, LFPI produced large increases in freezing behavior when rats were placed in a novel context [Fig. 2; F(5,30)=9.539, p<0.0001]. Exposed only to this minor stressor (i.e., at 2-week and 1-month post-injury measurements conducted prior to shock), LFPI rats injected with either MN166 or vehicle (Fig. 2, white and black bars, respectively) froze approximately twice as long as naïve or sham-operated rats (Fig. 2; light and dark grey bars, respectively; p<0.01). At the 2- and 3-month measurement time points, following the additional major stressor of shock (arrow in Fig. 2), freezing in both naïve and sham-operated rats remained constant at approximately 10%. Freezing in LFPI rats treated with MN166 remained consistently higher than their controls (p<0.001) but, while appearing higher compared to earlier post-injury measurements in the same animals, this increased freezing compared to naïve and sham-operated rats before (1 month) and following (2 months) shock did not reach significance (p=0.316). By contrast, LFPI + vehicle rats nearly doubled their freezing time, to approximately 50% (Fig. 2, black bars) compared to pre-shock values (p<0.001), freezing approximately twice as long as LFPI + MN166 rats (p<0.001), and five times as long as naïve and sham-operated controls (p<0.001), at the 2- and 3-month post-injury time points.

FIG. 2.

Freezing behavior in a novel context. Both surgically-naïve and sham-operated rats froze approximately 5–10% at post-surgical measurement points before (2 weeks and 1 month) after (2 and 3 months) foot shock (arrow). In contrast, LFPI rats froze significantly longer (∼ 20%) than controls before shock. After shock, untreated LFPI rats (LFPI + vehicle) nearly doubled their freezing time (∼ 50%), whereas treated LFPI rats (LFPI + MN166) showed only a slight increase (∼25%), that did not reach significance (p=0.316). The effects of injection alone (sham + MN166 and sham + vehicle) were to increase freezing behavior compared to un-injected naïve and sham-operated rats, particularly at the 2- and 3-month post-shock measurement time points, when freezing in these rats could not be distinguished from LFPI rats treated with MN166. Data represent mean±standard error of the mean (LFPI, lateral fluid percussion injury; TBI, traumatic brain injury).

The behavioral effects of injections alone, independent of LFPI, are reflected in the sham-surgery groups with injections of either MN166 or vehicle (Fig. 2, narrow and broad diagonal lines, respectively). Sham-operated rats tended to freeze more than un-injected naïve and sham-operated controls, reaching significance for both groups at the 2- and 3-month measurement time points (p<0.01), and suggesting that injections alone are aversive and can contribute to subsequent freezing. However, even at pre-shock measurement points, LFPI animals that received the same injections of MN166 or vehicle froze significantly more than injected controls (p<0.01), indicating substantial enhancement of freezing produced by LFPI. This effect became more apparent following shock, when LFPI + vehicle rats froze twice as long as the injected controls (p<0.001). By contrast, LFPI + MN166 rats were not distinguishable from either injected control group following shock, suggesting that their elevated freezing compared to naïve and sham-operated animals was the result of injections alone, and that MN166 eliminated the exaggerated freezing response to shock characterizing LFPI + vehicle rats.

OX-42 and GFAP immunoreactivity (reflecting microglia and astrocytic activation) was assessed in the insula, amygdala, and hippocampus in brain-injured rats for comparison to sham-operated and surgically-naïve rats. Representative images (40×), showing GFAP immunoreactivity in several of these regions, are shown in Figure 3, revealing normal astrocyte morphology in surgically-naïve and sham-operated rats. LFPI + vehicle rats showed clear signs of reactive astrocytes (Fig. 3, bottom row). LFPI rats treated with MN166 (Fig. 3, third row) were difficult to differentiate from sham-operated or surgically-naïve control groups.

FIG. 3.

Representative images depicting GFAP immunoreactivity (reflecting astrocytic activation) as assessed in the hippocampus, amygdala, and insula at 3 months post-injury. LFPI rats injected with vehicle showed clear signs of reactive astrocytes (bottom row), while naïve and sham-operated rats appeared to have normal astrocyte morphology. LFPI rats treated with MN166 (third row from top) were difficult to differentiate from surgically-naïve and sham-operated animals (LFPI, lateral fluid percussion injury; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; BLA, basolateral amygdala; CE, central amygdala).

Densitometry of GFAP labeling in all areas examined confirmed that activation of astrocytes was significantly greater in LFPI compared to all other groups in the insula [Fig. 4A, left bars; F(3,19)=13.17, p<0.0001], amygdala [Fig. 4B, left bars; F(3,18)=7.54, p<0.002], and hippocampus [Fig. 4C, left bars; F(3,15)=8.47, p<0.002]. In contrast, no differences in GFAP labeling were observed between the surgically-naïve, sham-operated, and LFPI + MN166 groups, in any of the regions examined. While MN166-treated LFPI rats were not distinguishable from surgically-naïve or sham-operated controls, post-hoc analyses revealed that LFPI + vehicle rats had significantly greater astrocyte activation in all three brain regions compared to controls (Fig. 4A–C): insula (p<0.002 versus the surgically-naive, sham-operated, and LFPI + MN166 groups), amygdala (p<0.02 versus the surgically-naive, sham-operated, and LFPI+MN166 groups). and hippocampus (p<0.03 versus the surgically-naive, sham-operated and LFPI + MN166 groups).

FIG. 4.

Regional and sub-regional analyses of microglial and astroglial activation in the hippocampus, amygdale, and insula at 3 months post-injury. (A-C) LFPI + vehicle injections induced a significant increase in GFAP labeling in all three regions compared to surgically-naïve, sham-operated, and LFPI + MN166-treated rats. (D) In the insula, OX-42 activation was greater in LFPI rats than in surgically-naïve, sham-operated, and LFPI + MN166-treated rats. There were no significant differences found between surgically-naïve, sham-operated, and LFPI + MN166-treated rats in either analysis. Data represent mean±standard error of the mean integrated densities of immunoreactivity (LFPI, lateral fluid percussion injury; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; BLA, basolateral amygdala; CE, central amygdala).

Analysis of GFAP immunoreactivity in sub-regions of the insula (Fig. 4A, right bars), amygdala (Fig. 4B, right bars), and hippocampus (Fig. 4C, right bars), also revealed no differences between the surgically-naïve, sham-operated, and LFPI + MN166 groups. As in the regional analysis, LFPI + vehicle rats showed increased astrocyte activation over controls in most sub-regions examined. In the insula, LFPI + vehicle rats showed significantly increased GFAP labeling in agranular [F(3,19)=16.778, p<0.0001], dysgranular [F(3,19)=6.042, p<0.005], and granular [F(3,19)=5.277, p<0.008] regions, compared to control groups. In the amygdala, GFAP labeling in LFPI + vehicle rats was significantly increased in the basolateral amygdala (BLA) [F(3,18)=4.050, p<0.023] and central amygdala (CE) [F(3,18)=5.012, p<0.011] nuclei, compared to controls. LFPI + vehicle rats also showed increased GFAP expression in the hippocampus, but this was only significant in CA3 [F(3,18)=3.810, p<0.03], and approached significance in CA1 [F(3,17)=3.234, p=0.055].

LFPI + vehicle rats also showed significantly increased microglia activation compared to control groups as measured by OX-42 labeling, but this was restricted to the insula [Fig. 4D; F(3,19)=5.59, p<0.007]. Analysis of sub-regions of the insula also revealed increases in microglial activation for LFPI + vehicle rats, and post-hoc comparisons showed that LFPI alone significantly increased OX-42 labeling in agranular [F(3,19)=11.186, p<0.0001] and granular [F(3,18)=3.740, p<0.03] areas, and that it approached significance [F(3,19)=2.742, p<0.072] in dysgranular areas. No differences in OX-42 labeling were observed between the surgically-naïve, sham-operated, and LFPI + MN166 groups, in any insular regions examined. No significant between-group differences were found in OX-42 expression for the amygdala or hippocampus.

Discussion

These data suggest a link between injury-induced brain inflammation and post-traumatic anxiety. Rats with LFPI display freezing responses to the minor stress of a novel environment that is 2–3 times normal, and which unlike controls, is nearly doubled by the delivery of a major foot-shock stressor. LFPI also results in marked reactive gliosis in brain regions associated with anxiety. The possibility that post-traumatic brain inflammation and gliosis may contribute to the anxiety-like behavior observed here is supported by the effects of the glial-cell activation inhibitor MN166. MN166 reduces reactive gliosis and TBI-induced freezing behavior, rendering these animals histologically and behaviorally indistinguishable from naïve and sham-operated controls. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report pharmacological immunosuppression resulting in the reduction of anxiety-like behaviors following TBI.

A possible mechanism for neuroimmune-induced post-traumatic anxiety

Our finding of prolonged reactive gliosis in brain structures including, but likely not confined to, the hippocampus, amygdala, and insular cortex, suggests that these structures may contribute to the persistent enhanced freezing of our brain-injured animals in reaction to a novel environment. All three structures have been implicated in rodent research investigating the pathogenesis of anxiety (Canteras et al., 2010; Davidson, 2002; Davis, 1992; Davis et al., 1994; Paulus and Stein, 2006; Rauch et al., 2006; Vyas et al., 2004) and fear behavior in the rat (Liu et al., 2010; Milad et al., 2009; Rosen and Donley, 2006; Sullivan, 2004).

The mechanisms by which immune responses may contribute to dysfunction of these structures remain to be determined. It is well established that LFPI in the rat results in activation of microglia and astrocytes as part of the innate immune response to insult. A number of studies indicate that LFPI-induced reactive gliosis follows a distinct time course, beginning with predominant microglia activation that peaks within a week (Clausen et al., 2009; Grady et al., 2003; Gueorguieva et al., 2008; Hill et al., 1996; Nonaka et al., 1999; Yu et al., 2010), but continues for several weeks and overlaps later with persistent astrocytic activation (D'Ambrosio et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2010). Microglia are resident macrophages and first responders to pathogens and neuronal insults in the CNS. They react rapidly, leading to activation of astrocytes and prolonged disruption of neuronal function (Herber et al., 2006; Iravani et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2009,2010). Several lesion paradigms have also shown a rapid microglial response, followed by delayed astrocyte reaction (Dusart and Schwab, 1994; Frank and Wolburg, 1996; Gehrmann et al., 1991; Liberatore et al., 1999; McCann et al., 1996).

Our results support this well-documented temporal relationship, suggesting that microglial activation precedes astrocytic activation and plays a role in the onset and maintenance of astrogliosis (Graeber and Kreutzberg, 1988; Hanisch, 2002; Herber et al., 2006; Iravani et al., 2005; McCann et al., 1996; Zhang et al., 2010). This time course is consistent with behavioral freezing responses in the present study, appearing rapidly within 2 weeks, but persisting unabated for the 3-month post-injury measurement period. It is also consistent with our immunohistochemistry results, indicating injury-induced astrocytic activation in all three regions of interest, the insula, amygdala, and hippocampus, at 3 months post-injury, but less activation of microglia, which was only significant in the insula. The lower levels of microglia expression are likely due to assessment at 3 months post-injury.

Trauma-related reactive gliosis is well known to result in the release of high levels of proinflammatory cytokines, specifically tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α; Fan et al., 1996; Lloyd et al., 2008; Taupin et al., 1993), interleukin-1β (IL-1β; Fan et al., 1995; Fassbender et al., 2000; Lloyd et al., 2008; Taupin et al., 1993; Yan et al., 2002), and interleukin-6 (IL-6; Lloyd et al., 2008; Taupin et al., 1993; Yan et al., 2002), which are central mediators of neuroinflammation following head injury (Fan et al., 1995,1996; Rothwell and Hopkins, 1995; Rothwell and Strijbos, 1995; Simi et al., 2007). Release of these proinflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-1β and TNF-α, pathologically increases neuronal excitability in all brain regions where it has been measured (Beattie et al., 2010; Maroso et al., 2010; Riazi et al., 2008; Rodgers et al., 2009; Schafers and Sorkin, 2008). While neuronal excitability and proinflammatory cytokine levels were not measured in the present study, neuroinflammation has been implicated in neuronal excitability of the amygdala and insular cortex and anxiety-like behavior by others using c-Fos labeling (Abrous et al., 1999; Ikeda et al., 2003; Kung et al., 2010). These same regions have also consistently been reported to be hyperexcitable in human imaging data across a variety of anxiety disorders (Carlson et al., 2011; Rauch et al., 1997; Shin and Liberzon, 2010; Shin et al., 2006; Simmons et al., 2006; Stein et al., 2007).

Attenuation of post-traumatic anxiety with MN166

Meta-analysis of the impact of pharmacological treatments on behavioral, cognitive, and motor outcomes after TBI in rodent models (Wheaton et al., 2011) indicates that of 16 treatment strategies evaluated to date, improved cognition and motor function have been reported, but few treatments have improved behaviors related to psychiatric dysfunction in general, and anxiety in particular. Exceptions to this are recent promising reports of treatments such as magnesium sulfate to limit excitotoxic damage (Fromm et al., 2004; O'Connor, 2003; Vink et al., 2003), and resveratrol to limit excitotoxicity, ischemia, and hypoxia (Sönmez et al., 2007), both increasing open-field exploration (resulting from decreased freezing), and therefore presumably decreasing post-injury anxiety.

Glial-targeted immunosuppression has also been found to be neuroprotective following TBI in rodents, resulting in increased structural preservation and improved functional outcomes (Hailer, 2008), including recent reports that MN166 significantly attenuated brain edema formation, cerebral atrophy, and apoptosis in neuronal cells following ischemic brain injury in rats, increasing neuronal survival rates (Lee et al., 2011). MN166 may reduce neuronal damage in regions involved in anxiety, mitigating the role of glial activation, neurotoxicity, and hyperexcitability in the subsequent development of anxiety-like behaviors. While not focused on post-traumatic anxiety, MN166 has been found to reduce intracellular calcium accumulation (Yanase et al., 1996), apoptosis, functional damage, and passive avoidance behaviors, following a transient ischemia model in rats (Yoshioka et al., 2002). Increasing evidence supports neuroinflammation, chronic inflammatory responses, proinflammatory cytokines, neuronal hyperexcitability, and secondary injury cascades in the pathophysiology of post-traumatic anxiety. The mechanisms of the effect of MN166 on TBI-induced anxiety-like behavior are not fully known. However, the results of this study provide evidence of a neuroprotective role for MN166 in attenuating and perhaps preventing development of post-traumatic anxiety.

Further exploration of the relationship between TBI, neuroimmune responses, neurocircuitry, and anxiety disorders, is important to better understand the sequelae of TBI, and will aid in the development of effective treatment strategies. The development of anxiety disorders following TBI is a complex and multifaceted problem, and finding treatments that work will require multifaceted approaches. The injury itself initiates many complex biological events, including glial activation, breakdown of the blood–brain barrier, excitotoxicity, and chronic neuroinflammation. While the primary injury often cannot be prevented, it may be possible to reduce the sequelae of secondary injury, leading to better functional and behavioral recovery following TBI. The present results, using peri-injury treatment with MN166 to prevent post-traumatic freezing behavior, not only suggest a role for neuroimmune inflammation in anxiety physiology, but similarly successful results with post-injury treatment could result in clinically-useful new agents to prevent post-traumatic anxiety in humans.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command grant PR100040, the Craig Hospital Gift Fund, a University of Colorado Innovative Seed Grant, Autism Speaks Pilot Study grant 7153, National Institutes of Health grant NS36981 to D.S.B., and National Institutes of Health grants DA024044, DA01767 to L.R.W.

Author Disclosure Statement

Kirk W. Johnson is chief science officer of MediciNova Inc., the pharmaceutical firm providing MN166 for this research. No other competing financial interests exist.

References

- Abrous D.N. Rodriguez J. Le Moal M. Moser P.C. Barneoud P. Effects of mild traumatic brain injury on immunoreactivity for the inducible transcription factors c-Fos, c-Jun, JunB, and Krox-24 in cerebral regions associated with conditioned fear responding. Brain Res. 1999;826:181–192. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloisi F. Immune function of microglia. Glia. 2001;36:165–179. doi: 10.1002/glia.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari M.A. Roberts K.N. Scheff S.W. A time course of contusion-induced oxidative stress and synaptic proteins in cortex in a rat model of TBI. J. Neurotrauma. 2008b;25:513–526. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari MA. Roberts K.N. Scheff S.W. Oxidative stress and modification of synaptic proteins in hippocampus after traumatic brain injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008a;45:443–452. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bains J.S. Shaw C.A. Neurodegenerative disorders in humans: the role of glutathione in oxidative stress-mediated neuronal death. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1997;25:335–358. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baratz R. Rubovitch V. Frenk H. Pick C.G. The influence of alcohol on behavioral recovery after mTBI in mice. J. Neurotrauma. 2010;27:555–563. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.0891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie M.S. Ferguson A.R. Bresnahan J.C. AMPA-receptor trafficking and injury-induced cell death. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2010;32:290–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07343.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard D.C. Blanchard R.J. Ethoexperimental approaches to the biology of emotion. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1998;39:43–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.39.020188.000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland S.T. Pillai R.N. Aronowski J. Grotta J.C. Schallert T. Early overuse and disuse of the affected forelimb after moderately severe intraluminal suture occlusion of the middle cerebral artery in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2001;126:33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00243-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland S.T. Schallert T. Strong R. Aronowski J. Grotta J.C. Early exclusive use of the affected forelimb after moderate transient focal ischemia in rats: functional and anatomic outcome. Stroke. 2000;31:1144–1152. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.5.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouilleret V. Cardamone L. Liu Y.R. Fang K. Myers D.E. O'Brien T.J. Progressive brain changes on serial manganese-enhanced MRI following traumatic brain injury in the rat. J. Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1999–2013. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.0943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner J.D. Randall P. Scott T.M. Bronen R.A. Seibyl J.P. Southwick S.M. Delaney R.C. McCarthy G. Charney D.S. Innis R.B. MRI-based measurement of hippocampal volume in patients with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1995;152:973–981. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G.C. Bal-Price A. Inflammatory neurodegeneration mediated by nitric oxide, glutamate, and mitochondria. Mol. Neurobiol. 2003;27:325–355. doi: 10.1385/MN:27:3:325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canteras N.S. Resstel L.B. Bertoglio L.J. Carobrez Ade P. Guimaraes F.S. Neuroanatomy of anxiety. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2010;2:77–96. doi: 10.1007/7854_2009_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson J.M. Greenberg T. Rubin D. Mujica-Parodi L.R. Feeling anxious: anticipatory amygdalo-insular response predicts the feeling of anxious anticipation. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2011;6:74–81. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernak I. Wang Z. Jiang J. Bian X. Savic J. Cognitive deficits following blast injury-induced neurotrauma: possible involvement of nitric oxide. Brain Inj. 2001b;15:593–612. doi: 10.1080/02699050010009559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernak I. Wang Z. Jiang J. Bian X. Savic J. Ultrastructural and functional characteristics of blast injury-induced neurotrauma. J. Trauma. 2001a;50:695–706. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200104000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y. Crichlow G.V. Vermeire J.J. Leng L. Du X. Hodsdon M.E. Bucala R. Cappello M. Gross M. Gaeta F. Johnson K. Lolis E.J. Allosteric inhibition of macrophage migration inhibitory factor revealed by ibudilast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:11313–11318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002716107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen F. Hanell A. Bjork M. Hillered L. Mir A.K. Gram H. Marklund N. Neutralization of interleukin-1beta modifies the inflammatory response and improves histological and cognitive outcome following traumatic brain injury in mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009;30:385–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler S.M. Pettus E.H. Hoffman S.W. Stein D.G. Tapered progesterone withdrawal enhances behavioral and molecular recovery after traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 2005;195:423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler S.M. Van Landingham J.W. Murphy A.Z. Stein D.G. Slow-release and injected progesterone treatments enhance acute recovery after traumatic brain injury. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2006b;84:420–428. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler S.M. Vanlandingham J.W. Stein D.G. Tapered progesterone withdrawal promotes long-term recovery following brain trauma. Exp. Neurol. 2006a;200:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.02.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Ambrosio R. Fairbanks J.P. Fender J.S. Born D.E. Doyle D.L. Miller J.W. Post-traumatic epilepsy following fluid percussion injury in the rat. Brain. 2004;127:304–314. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson R.J. Anxiety and affective style: role of prefrontal cortex and amygdala. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:68–80. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. Rainnie D. Cassell M. Neurotransmission in the rat amygdala related to fear and anxiety. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:208–214. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. The role of the amygdala in fear and anxiety. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1992;15:353–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.002033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellu F. Mayo W. Vallee M. Maccari S. Piazza P.V. Le Moal M. Simon H. Behavioral reactivity to novelty during youth as a predictive factor of stress-induced corticosterone secretion in the elderly—a life-span study in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21:441–453. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(96)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon C.E. Bao J. Long D.A. Hayes R.L. Reduced evoked release of acetylcholine in the rodent hippocampus following traumatic brain injury. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1996;53:679–686. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusart I. Schwab M.E. Secondary cell death and the inflammatory reaction after dorsal hemisection of the rat spinal cord. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1994;6:712–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L. Young P.R. Barone F.C. Feuerstein G.Z. Smith D.H. McIntosh T.K. Experimental brain injury induces differential expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha mRNA in the CNS. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1996;36:287–291. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00274-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L. Young P.R. Barone F.C. Feuerstein G.Z. Smith D.H. McIntosh T.K. Experimental brain injury induces expression of interleukin-1 beta mRNA in the rat brain. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1995;30:125–130. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)00287-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina C. Aloisi F. Meinl E. Astrocytes are active players in cerebral innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassbender K. Schneider S. Bertsch T. Schlueter D. Fatar M. Ragoschke A. Kuhl S. Kischka U. Hennerici M. Temporal profile of release of interleukin-1beta in neurotrauma. Neurosci. Lett. 2000;284:135–138. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00977-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank M. Wolburg H. Cellular reactions at the lesion site after crushing of the rat optic nerve. Glia. 1996;16:227–240. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199603)16:3<227::AID-GLIA5>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey L.C. Hellier J. Unkart C. Lepkin A. Howard A. Hasebroock K. Serkova N. Liang L. Patel M. Soltesz I. Staley K. A novel apparatus for lateral fluid percussion injury in the rat. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2009;177:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromm L. Heath D.L. Vink R. Nimmo A.J. Magnesium attenuates post-traumatic depression/anxiety following diffuse traumatic brain injury in rats. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2004;23:529S–533S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasque P. Dean Y.D. McGreal E.P. VanBeek J. Morgan B.P. Complement components of the innate immune system in health and disease in the CNS. Immunopharmacology. 2000;49:171–186. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(00)80302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrmann. J. Microglia: a sensor to threats in the nervous system? Res. Virol. 1996;147:79–88. doi: 10.1016/0923-2516(96)80220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrmann J. Schoen S.W. Kreutzberg G.W. Lesion of the rat entorhinal cortex leads to a rapid microglial reaction in the dentate gyrus. A light and electron microscopical study. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:442–455. doi: 10.1007/BF00293378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson L.C. Hastings S.F. McPhee I. Clayton R.A. Darroch C.E. Mackenzie A. Mackenzie F.L. Nagasawa M. Stevens P.A. Mackenzie S.J. The inhibitory profile of Ibudilast against the human phosphodiesterase enzyme family. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006;538:39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Scarano F. Baltuch G. Microglia as mediators of inflammatory and degenerative diseases. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1999;22:219–240. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss C.W. Hoffman S.W. Stein D.G. Behavioral effects and anatomic correlates after brain injury: a progesterone dose-response study. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2003;76:231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady M.S. Charleston J.S. Maris D. Witgen B.M. Lifshitz J. Neuronal and glial cell number in the hippocampus after experimental traumatic brain injury: analysis by stereological estimation. J. Neurotrauma. 2003;20:929–941. doi: 10.1089/089771503770195786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeber M.B. Kreutzberg G.W. Delayed astrocyte reaction following facial nerve axotomy. J. Neurocytol. 1988;17:209–220. doi: 10.1007/BF01674208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueorguieva I. Clark S.R. McMahon C.J. Scarth S. Rothwell N.J. Tyrrell P.J. Hopkins S.J. Rowland M. Pharmacokinetic modelling of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of patients following subarachnoid haemorrhage. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008;65:317–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.03026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailer N.P. Immunosuppression after traumatic or ischemic CNS damage: it is neuroprotective and illuminates the role of microglial cells. Prog. Neurobiol. 2008;84:211–233. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch U.K. Microglia as a source and target of cytokines. Glia. 2002;40:140–155. doi: 10.1002/glia.10161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herber D.L. Maloney J.L. Roth L.M. Freeman M.J. Morgan D. Gordon M.N. Diverse microglial responses after intrahippocampal administration of lipopolysaccharide. Glia. 2006;53:382–391. doi: 10.1002/glia.20272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill S.J. Barbarese E. McIntosh T.K. Regional heterogeneity in the response of astrocytes following traumatic brain injury in the adult rat. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1996;55:1221–1229. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199612000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge E.A. Brandstetter K. Moshier S. Pollack M.H. Wong K.K. Simon N.M. Broad spectrum of cytokine abnormalities in panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Depress. Anxiety. 2009;26:447–455. doi: 10.1002/da.20564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K. Onaka T. Yamakado M. Nakai J. Ishikawa T.O. Taketo M.M. Kawakami K. Degeneration of the amygdala/piriform cortex and enhanced fear/anxiety behaviors in sodium pump alpha2 subunit (Atp1a2)-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:4667–4676. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04667.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iravani M.M. Leung C.C. Sadeghian M. Haddon C.O. Rose S. Jenner P. The acute and the long-term effects of nigral lipopolysaccharide administration on dopaminergic dysfunction and glial cell activation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2005;22:317–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones N.C. Cardamone L. Williams J.P. Salzberg M.R. Myers D. O'Brien T.J. Experimental traumatic brain injury induces a pervasive hyperanxious phenotype in rats. J. Neurotrauma. 2008;25:1367–1374. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline A.E. Wagner A.K. Westergom B.P. Malena R.R. Zafonte R.D. Olsen A.S. Sozda C.N. Luthra P. Panda M. Cheng J.P. Aslam H.A. Acute treatment with the 5-HT(1A) receptor agonist 8-OH-DPAT and chronic environmental enrichment confer neurobehavioral benefit after experimental brain trauma. Behav. Brain Res. 2007;177:186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung J.C. Chen T.C. Shyu B.C. Hsiao S. Huang A.C. Anxiety- and depressive-like responses and c-fos activity in preproenkephalin knockout mice: oversensitivity hypothesis of enkephalin deficit-induced posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Biomed. Sci. 2010;17:29. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-17-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledeboer A. Hutchinson M.R. Watkins L.R. Johnson K.W. Ibudilast (AV-411) A new class therapeutic candidate for neuropathic pain and opioid withdrawal syndromes. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2007;16:935–950. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.7.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.Y. Cho E. Ko Y.E. Kim I. Lee K.J. Kwon S.U. Kang D.W. Kim J.S. Ibudilast, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor with anti-inflammatory activity, protects against ischemic brain injury in rats. Brain Res. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehnardt S. Innate immunity and neuroinflammation in the CNS: the role of microglia in Toll-like receptor-mediated neuronal injury. Glia. 2010;58:253–263. doi: 10.1002/glia.20928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberatore G.T. Jackson-Lewis V. Vukosavic S. Mandir A.S. Vila M. McAuliffe W.G. Dawson V.L. Dawson T.M. Przedborski S. Inducible nitric oxide synthase stimulates dopaminergic neurodegeneration in the MPTP model of Parkinson disease. Nat. Med. 1999;5:1403–1409. doi: 10.1038/70978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.R. Cardamone L. Hogan R.E. Gregoire M.C. Williams J.P. Hicks R.J. Binns D. Koe A. Jones N.C. Myers D.E. O'Brien T.J. Bouilleret V. Progressive metabolic and structural cerebral perturbations after traumatic brain injury: an in vivo imaging study in the rat. J. Nucl. Med. 2010;51:1788–1795. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.078626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd E. Somera-Molina K. Van Eldik L.J. Watterson D.M. Wainwright M.S. Suppression of acute proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine upregulation by post-injury administration of a novel small molecule improves long-term neurologic outcome in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:28. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loram L.C. Harrison J.A. Sloane E.M. Hutchinson M.R. Sholar P. Taylor F.R. Berkelhammer D. Coats B.D. Poole S. Milligan E.D. Maier S.F. Rieger J. Watkins L.R. Enduring reversal of neuropathic pain by a single intrathecal injection of adenosine 2A receptor agonists: a novel therapy for neuropathic pain. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:14015–14025. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3447-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroso M. Balosso S. Ravizza T. Liu J. Aronica E. Iyer A.M. Rossetti C. Molteni M. Casalgrandi M. Manfredi A.A. Bianchi M.E. Vezzani A. Toll-like receptor 4 and high-mobility group box-1 are involved in ictogenesis and can be targeted to reduce seizures. Nat. Med. 2010;16:413–419. doi: 10.1038/nm.2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann M.J. O'Callaghan J.P. Martin P.M. Bertram T. Streit W.J. Differential activation of microglia and astrocytes following trimethyl tin-induced neurodegeneration. Neuroscience. 1996;72:273–281. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00526-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh T.K. Vink R. Noble L. Yamakami I. Fernyak S. Soares H. Faden A.L. Traumatic brain injury in the rat: characterization of a lateral fluid-percussion model. Neuroscience. 1989;28:233–244. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90247-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad M.R. Pitman R.K. Ellis C.B. Gold A.L. Shin L.M. Lasko N.B. Zeidan M.A. Handwerger K. Orr S.P. Rauch S.L. Neurobiological basis of failure to recall extinction memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2009;66:1075–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno T. Kurotani T. Komatsu Y. Kawanokuchi J. Kato H. Mitsuma N. Suzumura A. Neuroprotective role of phosphodiesterase inhibitor ibudilast on neuronal cell death induced by activated microglia. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monleon S. D'Aquila P. Parra A. Simon V.M. Brain P.F. Willner P. Attenuation of sucrose consumption in mice by chronic mild stress and its restoration by imipramine. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1995;117:453–457. doi: 10.1007/BF02246218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore E.L. Terryberry-Spohr L. Hope D.A. Mild traumatic brain injury and anxiety sequelae: a review of the literature. Brain Inj. 2006;20:117–132. doi: 10.1080/02699050500443558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey T.K. Pellis S.M. Pellis V.C. Teitelbaum P. Seemingly paradoxical jumping in cataleptic haloperidol-treated rats is triggered by postural instability. Behav. Brain Res. 1989;35:195–207. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(89)80141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitz A.J. Dobner J.J. Matulionis D.H. Pneumatic tourniquet application and nerve integrity: motor function and electrophysiology. Exp. Neurol. 1986;94:264–279. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(86)90101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka M. Chen X.H. Pierce J.E. Leoni M.J. McIntosh T.K. Wolf J.A. Smith D.H. Prolonged activation of NF-kappaB following traumatic brain injury in rats. J. Neurotrauma. 1999;16:1023–1034. doi: 10.1089/neu.1999.16.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor C.A. Cernak I. Vink R. Interaction between anesthesia, gender, and functional outcome task following diffuse traumatic brain injury in rats. J. Neurotrauma. 2003;20:533–541. doi: 10.1089/089771503767168465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus M.P. Stein M.B. An insular view of anxiety. Biol. Psychiatry. 2006;60:383–387. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellis S.M. Pellis V.C. Teitelbaum P. Air righting without the cervical righting reflex in adult rats. Behav. Brain Res. 1991b;45:185–188. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(05)80084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellis S.M. Whishaw I.Q. Pellis V.C. Visual modulation of vestibularly-triggered air-righting in rats involves the superior colliculus. Behav. Brain Res. 1991a;46:151–156. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(05)80108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao V. Lyketsos C. Neuropsychiatric sequelae of traumatic brain injury. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:95–103. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.41.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch S.L. Savage C.R. Alpert N.M. Fischman A.J. Jenike M.A. The functional neuroanatomy of anxiety: a study of three disorders using positron emission tomography and symptom provocation. Biol. Psychiatry. 1997;42:446–452. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(97)00145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch S.L. Shin L.M. Phelps E.A. Neurocircuitry models of posttraumatic stress disorder and extinction: human neuroimaging research—past, present, and future. Biol. Psychiatry. 2006;60:376–382. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riazi K. Galic M.A. Kuzmiski J.B. Ho W. Sharkey K.A. Pittman Q.J. Microglial activation and TNFalpha production mediate altered CNS excitability following peripheral inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:17151–17156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806682105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers K.M. Hutchinson M.R. Northcutt A. Maier S.F. Watkins L.R. Barth D.S. The cortical innate immune response increases local neuronal excitability leading to seizures. Brain. 2009;132:2478–2486. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolan P. Hutchinson M. Johnson K. Ibudilast: a review of its pharmacology, efficacy and safety in respiratory and neurological disease. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2009;10:2897–2904. doi: 10.1517/14656560903426189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen J.B. Donley M.P. Animal studies of amygdala function in fear and uncertainty: relevance to human research. Biol. Psychol. 2006;73:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell N.J. Hopkins S.J. Cytokines and the nervous system II: Actions and mechanisms of action. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:130–136. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93890-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell N.J. Strijbos P.J. Cytokines in neurodegeneration and repair. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 1995;13:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(95)00018-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanberg P.R. Bunsey M.D. Giordano M. Norman A.B. The catalepsy test: its ups and downs. Behav. Neurosci. 1988;102:748–759. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.102.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky R.M. Glucocorticoids and hippocampal atrophy in neuropsychiatric disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2000;57:925–935. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafers M. Sorkin L. Effect of cytokines on neuronal excitability. Neurosci. Lett. 2008;437:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schallert T. Behavioral tests for preclinical intervention assessment. NeuroRx. 2006;3:497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.nurx.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schallert T. De Ryck M. Whishaw I.Q. Ramirez V.D. Teitelbaum P. Excessive bracing reactions and their control by atropine and L-DOPA in an animal analog of Parkinsonism. Exp. Neurol. 1979;64:33–43. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(79)90003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schallert T. Fleming S.M. Leasure J.L. Tillerson J.L. Bland S.T. CNS plasticity and assessment of forelimb sensorimotor outcome in unilateral rat models of stroke, cortical ablation, parkinsonism and spinal cord injury. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:777–787. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt O.I. Heyde C.E. Ertel W. Stahel P.F. Closed head injury—an inflammatory disease? Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2005;48:388–399. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin L.M. Liberzon I. The neurocircuitry of fear, stress, and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:169–191. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin L.M. Rauch S.L. Pitman R.K. Amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampal function in PTSD. Ann NY Acad. Sci. 2006;1071:67–79. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozaki T. Hayakata T. Tasaki O. Hosotubo H. Fuijita K. Mouri T. Tajima G. Kajino K. Nakae H. Tanaka H. Shimazu T. Sugimoto H. Cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of anti-inflammatory mediators in early-phase severe traumatic brain injury. Shock. 2005;23:406–410. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000161385.62758.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simi A. Tsakiri N. Wang P. Rothwell N.J. Interleukin-1 and inflammatory neurodegeneration. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007;35:1122–1126. doi: 10.1042/BST0351122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons A. Strigo I. Matthews S.C. Paulus M.P. Stein M.B. Anticipation of aversive visual stimuli is associated with increased insula activation in anxiety-prone subjects. Biol. Psychiatry. 2006;60:402–409. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sönmez U. Sönmez A. Erbil G. Tekmen I. Baykara B. Neuroprotective effects of resveratrol against traumatic brain injury in immature rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2007;420:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spivak B. Shohat B. Mester R. Avraham S. Gil-Ad I. Bleich A. Valevski A. Weizman A. Elevated levels of serum interleukin-1 beta in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 1997;42:345–348. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00375-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein M.B. Simmons A.N. Feinstein J.S. Paulus M.P. Increased amygdala and insula activation during emotion processing in anxiety-prone subjects. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164:318–327. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg E.M. Neural-immune interactions in health and disease. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:2641–2647. doi: 10.1172/JCI119807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan R.M. Hemispheric asymmetry in stress processing in rat prefrontal cortex and the role of mesocortical dopamine. Stress. 2004;7:131–143. doi: 10.1080/102538900410001679310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taupin V. Toulmond S. Serrano A. Benavides J. Zavala F. Increase in IL-6, IL-1 and TNF levels in rat brain following traumatic lesion. Influence of pre- and post-traumatic treatment with Ro5 4864, a peripheral-type (p site) benzodiazepine ligand. J. Neuroimmunol. 1993;42:177–185. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(93)90008-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson H.J. Lifshitz J. Marklund N. Grady M.S. Graham D.I. Hovda D.A. McIntosh T.K. Lateral fluid percussion brain injury: a 15-year review and evaluation. J. Neurotrauma. 2005;22:42–75. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Town T. Nikolic V. Tan J. The microglial “activation” continuum: from innate to adaptive responses. J. Neuroinflammation. 2005;2:24. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-2-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker P. Ruwe W.D. Masters B. Parker D.E. Hossain A. Trautman R.P. Wyatt D.B. Neuroimmune and cortisol changes in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and placebo treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2004;56:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaishnavi S. Rao V. Fann J.R. Neuropsychiatric problems after traumatic brain injury: unraveling the silent epidemic. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:198–205. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink R. O'Connor C.A. Nimmo A.J. Heath D.L. Magnesium attenuates persistent functional deficits following diffuse traumatic brain injury in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2003;336:41–44. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01244-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Känel R. Hepp U. Kraemer B. Traber R. Keel M. Mica L. Schnyder U. Evidence for low-grade systemic proinflammatory activity in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Psychiatric Res. 2007;41:744–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas A. Pillai A.G. Chattarji S. Recovery after chronic stress fails to reverse amygdaloid neuronal hypertrophy and enhanced anxiety-like behavior. Neuroscience. 2004;128:667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A.K. Postal B.A. Darrah S.D. Chen X. Khan A.S. Deficits in novelty exploration after controlled cortical impact. J. Neurotrauma. 2007;24:1308–1320. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F. Xu S. Shen X. Guo X. Peng Y. Yang J. Spinal macrophage migration inhibitory factor is a major contributor to rodent neuropathic pain-like hypersensitivity. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:643–659. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31820a4bf3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton P. Mathias J.L. Vink R. Impact of pharmacological treatments on outcome in adult rodents after traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis. J. Psychopharmacol. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0269881110388331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P. Validity, reliability and utility of the chronic mild stress model of depression: a 10-year review and evaluation. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 1997;134:319–329. doi: 10.1007/s002130050456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodlee M.T. Asseo-Garcia A.M. Zhao X. Liu S.J. Jones T.A. Schallert T. Testing forelimb placing “across the midline” reveals distinct, lesion-dependent patterns of recovery in rats. Exp. Neurol. 2005;191:310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi K. Tada Y. Kitazato K.T. Tamura T. Satomi J. Nagahiro S. Ibudilast inhibits cerebral aneurysms by down-regulating inflammation-related molecules in the vascular wall of rats. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:551–559. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000365771.89576.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanase H. Mitani A. Kataoka K. Ibudilast reduces intracellular calcium elevation induced by in vitro ischaemia in gerbil hippocampal slices. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1996;23:317–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb02830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan F. Li S. Liu J. Zhang W. Chen C. Liu M. Xu L. Shao J. Wu H. Wang Y. Liang K. Zhao C. Lei X. Incidence of senile dementia and depression in elderly population in Xicheng District, Beijing, an epidemiologic study. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2002;82:1025–1028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H.Q. Banos M.A. Herregodts P. Hooghe R. Hooghe-Peters E.L. Expression of interleukin (IL)-1 beta, IL-6 and their respective receptors in the normal rat brain and after injury. Eur. J. Immunol. 1992;22:2963–2971. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka M. Suda N. Mori K. Ueno K. Itoh Y. Togashi H. Matsumoto M. Effects of ibudilast on hippocampal long-term potentiation and passive avoidance responses in rats with transient cerebral ischemia. Pharmacol. Res. 2002;45:305–311. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2002.0949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu I. Inaji M. Maeda J. Okauchi T. Nariai T. Ohno K. Higuchi M. Suhara T. Glial cell-mediated deterioration and repair of the nervous system after traumatic brain injury in a rat model as assessed by positron emission tomography. J. Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1463–1475. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D. Hu X. Qian L. O'Callaghan J.P. Hong J.S. Astrogliosis in CNS pathologies: is there a role for microglia? Mol. Neurobiol. 2010;41:232–241. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8098-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D. Hu X. Qian L. Wilson B. Lee C. Flood P. Langenbach R. Hong J.S. Prostaglandin E2 released from activated microglia enhances astrocyte proliferation in vitro. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009;238:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]