Abstract

The remarkable regeneration capability of plant tissues or organs under culture conditions has underlain an extensive practice for decades. The initial step in plant in vitro regeneration often involves the induction of a pluripotent cell mass termed callus, which is driven by the phytohormone auxin and occurs via a root development pathway. However, the key molecules governing callus formation remain unknown. Here we demonstrate that Arabidopsis LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES DOMAIN (LBD)/ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2-LIKE (ASL) transcription factors are involved in the control of callus formation program. The four LBD genes downstream of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTORs (ARFs), LBD16, LBD17, LBD18 and LBD29, are rapidly and dramatically induced by callus-inducing medium (CIM) in multiple organs. Ectopic expression of each of the four LBD genes in Arabidopsis is sufficient to trigger spontaneous callus formation without exogenous phytohormones, whereas suppression of LBD function inhibits the callus formation induced by CIM. Moreover, the callus triggered by LBD resembles that induced by CIM by characteristics of ectopically activated root meristem genes and efficient regeneration capacity. These findings define LBD transcription factors as key regulators in the callus induction process, thereby establishing a molecular link between auxin signaling and the plant regeneration program.

Keywords: LBD, callus formation, auxin, regeneration, Arabidopsis

Introduction

Plant cells have been widely believed to have pluripotency because most of the already differentiated organs or tissues from higher plants are capable of regenerating new organs or even whole plants under appropriate culture conditions 1, 2. The in vitro regeneration programs of plants are mainly mediated by phytohormones auxin and cytokinin 3, 4. Remarkably, a low auxin/cytokinin ratio in medium promotes shoot regeneration while a high ratio stimulates root formation; and an optimal ratio of auxin/cytokinin induces the formation of callus 3, 5. In a commonly used Arabidopsis regeneration system, the pieces of organs (explants) are pre-incubated on auxin-rich callus-inducing medium (CIM) to form callus. Subsequent cultures of callus on shoot-inducing medium (SIM) or root-inducing medium (RIM) with different auxin/cytokinin ratios lead to the regeneration of shoots or roots, respectively 5, 6. Similar manipulations have been extensively employed for in vitro propagation and gene transformation in a wide variety of plant species for more than half a century 2.

Callus induction is often the initial step in a typical in vitro plant regeneration system. Because callus has an unorganized structure and high regeneration capability, callus induction has long been believed to be a process whereby already differentiated cells dedifferentiate to acquire pluripotency 7, 8, 9. The gene expression and proteomic profile analyses of Arabidopsis root or cotyledon explants on CIM showed that profound changes occurred in both the transcriptome and proteome during callus induction 6, 10, 11. However, since direct organogenesis has been observed when some of plant tissues or organs were cultured on SIM or RIM 12, 13, there is another possibility that some kind of pre-existing cells within explants are potentially stem cell-like, and might selectively proliferate to form callus. The developmental events during callus induction were characterized in Arabidopsis only recently. Atta et al. 12 showed that the calluses from root and hypocotyl explants were originated from xylem pericycle or pericycle-like cells, and callus formation occurred similar to the establishment of lateral root meristems with a characteristic of expression of a few root meristem-marker genes. A recent work also suggested that callus formation in Arabidopsis aerial organs, such as cotyledon and petal, was via activation of a root development pathway 14. These studies implicate that callus formation may not be a simple reprogramming process, and that ectopic activation of the root development program appears to be a common mechanism underlying callus induction 14. Although auxin has been shown to be essential for the callus induction process 3, 15, the molecular link between auxin signaling and callus induction has never been established in the in vitro plant regeneration system.

The LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES DOMAIN (LBD) (also known as ASL for ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2-LIKE) proteins belong to a family of plant-specific transcription factors, characterized by an N-terminal-conserved LOB/AS2 domain with a CX2CX6CX3C motif and a Leu zipper-like sequence 16, 17. The LBD family comprises 43 members in Arabidopsis, 35 in rice and 57 in poplar 18, 19, 20, 21. Functional characterization of several LBD members revealed that LBD genes play critical roles in defining lateral organ boundaries and regulating many aspects of plant development, including root, leaf, inflorescence and embryo development. For example, the founding member of this family, Arabidopsis LBD6/AS2, is involved not only in a regulatory loop that maintains shoot meristem and defines lateral organ boundary antagonistically with SHOOT MERISTEMLESS 22, but also in the control of leaf polarity and flower development by interacting with AS1, a MYB transcription factor 23, 24. Arabidopsis LBD30 and LBD18 positively regulate xylem differentiation in leaf and root 25, and poplar LBD1 is involved in the regulation of secondary growth 26. Importantly, LBD genes are critical for root development in both dicots and monocots. Arabidopsis LBD16, LBD29 and LBD18 have been found to be direct or indirect targets of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTORs (ARFs), ARF7 and ARF19, to synergistically regulate lateral root formation 27, 28, demonstrating that LBD genes are directly involved in the auxin signal cascades in lateral root patterning. Rice CROWN ROOTLESS1 and maize rootless concerning crown and seminal roots, two close homologues of Arabidopsis LBD29, regulate the formation of monocot-specific crown roots 29, 30, 31. Recent studies also indicate that some of LBD members, such as Arabidopsis LBD37, LBD38, LBD39 and rice LBD37, are involved in the regulation of anthocyanin and nitrogen metabolism 32, 33.

Here we report that the callus induction in Arabidopsis regeneration is mediated by LBD genes. We show that the four LBD genes downstream of ARFs, LBD16, LBD17, LBD18 and LBD29, are highly induced by CIM, and that overexpression of each of the LBD genes promotes callus formation in the absence of exogenous phytohormones, while suppression of LBD function inhibits the callus induction process. We also provide evidence that LBD-directed callus formation resembles callus induction by CIM. These results identify LBD transcription factors as key regulators that mediate auxin signals and direct callus formation in the in vitro plant regeneration program.

Results

LBD16, LBD17, LBD18 and LBD29 are dramatically and rapidly induced by CIM

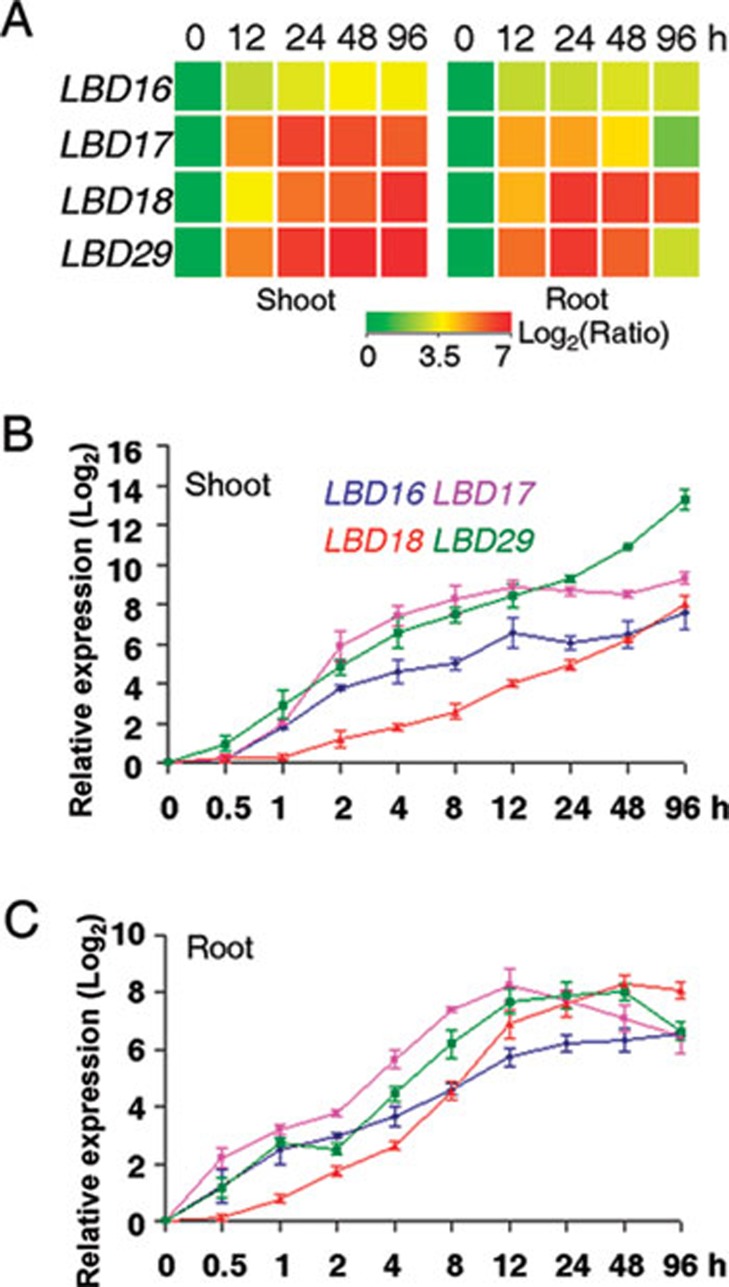

To identify key regulators mediating callus formation in the plant regeneration system, we used the Affymetrix Arabidopsis ATH1 GeneChips and analyzed the genome-scale transcriptomes of both root and shoot (aerial organs) explants of Arabidopsis seedlings after incubation on CIM. Previous studies have indicated that incubation of Arabidopsis root and hypocotyl explants on CIM for 3-5 days is sufficient to result in visible callus initiation from xylem pericycles 8, 12, and that callus formation in multiple organs follows a same root development pathway 12, 14. We therefore compared gene expression profiles between original explants and those incubated on CIM for 12, 24, 48 and 96 h, respectively, and focused on the genes that were up or downregulated by CIM in both shoot and root explants. Among a set of differentially expressed genes identified (GEO accession number GSE29543), the four LBD genes, LBD16, LBD17, LBD18 and LBD29, were dramatically upregulated by CIM in both explants (from 7- to 212-fold) (Figure 1A). To validate this result, we further performed quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) and examined their expression levels in the explants transferred to CIM. As shown in Figure 1B and 1C, the four LBD genes were also early responsive to CIM, among which LBD16, LBD17 and LBD29 were apparently induced by CIM within 1 h, while induction of LBD18 occurred slightly later. These results demonstrate that the four LBD genes are rapidly and highly induced by CIM during callus induction.

Figure 1.

LBD16, LBD17, LBD18 and LBD29 are highly induced in root and shoot explants during callus induction. (A) Clustering displays of the relative expression ratios (log2) of LBD16, LBD17, LBD18 and LBD29 in shoot and root explants on callus inducing medium (CIM). Root and shoot explants from ten-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings were incubated on CIM for 0, 12, 24, 48 and 96 h, and the relative expression level of each LBD gene at each time point on CIM was versus to that of original explants (at 0 h). Data showed the averages of three independent microarray experiments. (B-C) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses of the expression of LBD16 (blue), LBD17 (purple), LBD18 (red) and LBD29 (green) in shoot (B) and root (C) explants on CIM. The expression level of each gene at each time point after normalized to ACTIN2 was versus to that at 0 h, and the data (log2) from three biological replicates were shown as means ± SD.

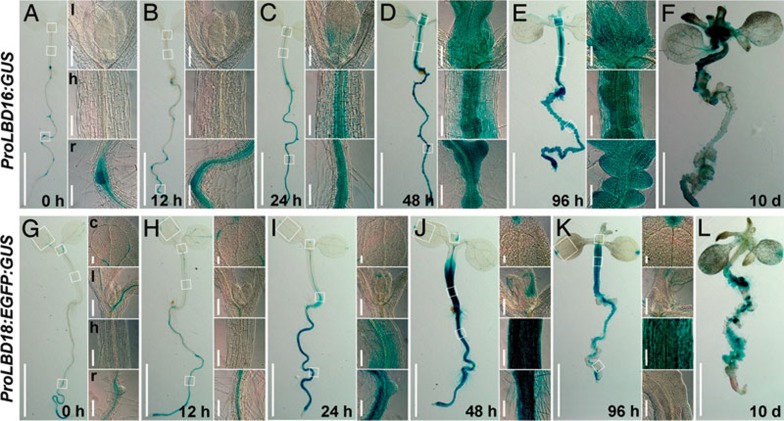

Temporal and spatial expression of LBD16 and LBD18 during callus formation

Previous studies showed that LBD16 and LBD17 were expressed in young lateral roots and LBD29 in lateral root primordia, while LBD18 was more ubiquitously detected in most organs 19, 28, 34. To investigate the temporal and spatial expression of LBD genes during callus induction, we chose LBD16 and LBD18 as the representatives and carefully examined their expression patterns during callus induction using ProLBD16:GUS and ProLBD18:EGFP:GUS transgenic seedlings. Consistent with previous observations 27, 28, 35, LBD16 was only expressed in LRP, root stele nearby LRP and emerged lateral roots (Figure 2A). However, after seedlings were incubated on CIM for 12 h, GUS staining expanded to the stele of elongation zone in primary roots (Figure 2B), and subsequently to leaves and the vascular tissues of both roots and hypocotyls after 24 h (Figure 2C). The GUS activity was significantly enhanced from 48 to 96 h in these organs where callus was initiating (Figure 2D and 2E), and then declined in formed calluses at 10 days (Figure 2F). Similarly, although LBD18 was originally expressed in the vascular tissues of shoots and stele of the elongation zone in primary roots (Figure 2G), the ectopic induction of LBD18 by CIM was observed in both roots and hypocotyls where callus formation occurred subsequently (Figure 2H-2L). These observations strongly suggest that the dynamic expression of these LBD genes correlates with the callus initiation process.

Figure 2.

Temporal and spatial expression of LBD16 and LBD18 during callus induction. (A-F) Temporal and spatial expression of LBD16 assayed by ProLBD16:GUS reporter gene. Five-day-old seedlings (A) and those incubated on CIM for 12 h (B), 24 h (C), 48 h (D), 96 h (E) and 10 days (F) were assayed for GUS staining for 4 h. Insets showed the enlarged images of regions in different organs circled by squares. (G-L) Expression of LBD18 assayed by GUS staining. Five-day-old ProLBD18:EGFP:GUS transgenic seedlings (G) and those incubated on CIM (H-L) were assayed for GUS staining for 3 h. l, leaf; h, hypocotyl; r, root; c, cotyledon. Bars = 2 mm in seedlings, and 100 μm in insets.

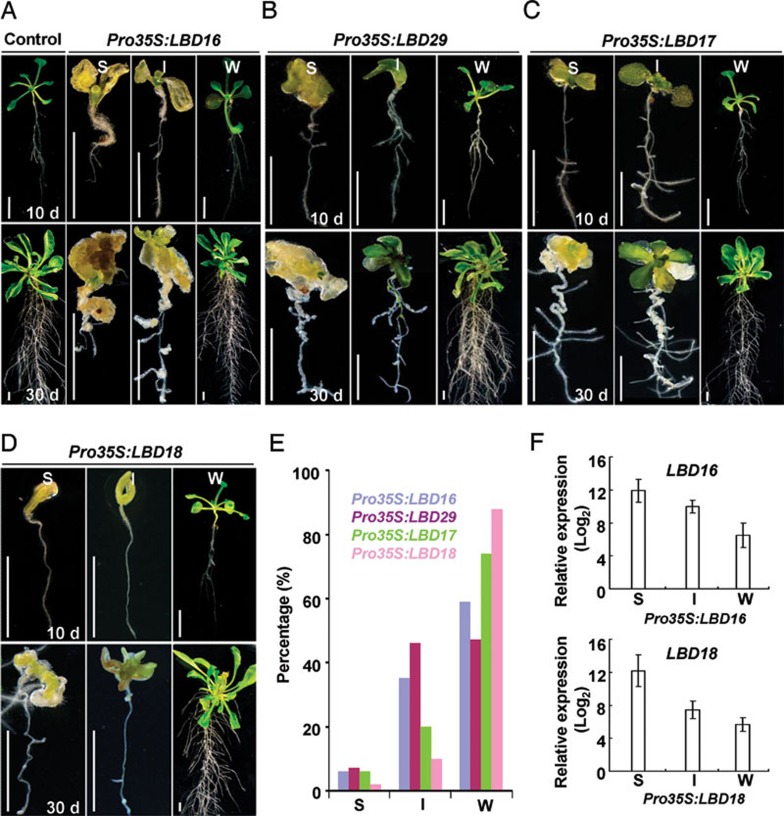

Overexpression of LBD genes is sufficient to trigger callus formation without exogenous phytohormones

Of the 43 LBD members in the Arabidopsis genome, the expressions of LBD16, LBD17, LBD18 and LBD29 are all inducible by auxin 28, 36, a phytohormone required for callus induction in in vitro plant regeneration 15. More importantly, LBD16, LBD29 and LBD18 have been shown to regulate lateral root formation, a pathway that callus formation may follow 12, 14, 27, 28. Therefore, we hypothesized that the ectopic expression of LBD genes induced by CIM may be responsible for the auxin-induced callus formation program. To test this, we ectopically expressed LBD16, LBD17, LBD18 or LBD29 under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter in Arabidopsis, respectively. As expected, the recovered T1 transgenic seedlings overexpressing each of the four LBD genes exhibited a varied degree of spontaneous callus formation when grown on medium without exogenous phytohormones (Figure 3). We generally categorized the phenotypes into strong, intermediate and weak types. Of 610 Pro35S:LBD16 transgenic seedlings recovered, ∼6% of seedlings (strong) exhibited an early arrest of postembryonic development and all their organs directly developed into calluses, ∼35% of seedlings (intermediate) developed with completely callused aerial organs and partially callused roots, and ∼59% of seedlings (weak) had more lateral roots with visible calluses (Figure 3A and 3E). Similarly, autonomous callus formation was also observed in various organs of recovered transgenic seedlings overexpressing LBD29, LBD17 or LBD18, respectively (Figure 3B-3D). Moreover, qRT-PCR analyses with Pro35S:LBD16 and Pro35S:LBD18 transformants clearly demonstrated that the varied degrees of callus-forming phenotype correlated with the expression levels of LBD transgenes (Figure 3F). These findings indicate that ectopic expression of the LBD genes is sufficient to trigger callus formation in vivo.

Figure 3.

Ectopic expression of LBD genes triggers spontaneous callus formation in vivo. (A) Phenotype of recovered Pro35S:LBD16 T1 seedlings with strong (S), intermediate (I) or weak (W) type. Ten-day-old control and Pro35S:LBD16 transgenic seedlings (upper panel) were grown on B5 medium without exogenous phytohormones for 20 days (lower panel). Bars = 5 mm. (B-D) Morphology of recovered S, I or W type seedlings overexpressing LBD29 (B), LBD17 (C) and LBD18 (D). Ten-day-old seedlings (upper panel) were grown on B5 medium without phytohormones for 20 days (lower panel). Bars = 5 mm. (E) Percentages of S, I or W type transgenic seedlings described in A-D. Total transgenic seedlings examined for Pro35S:LBD16, Pro35S:LBD29, Pro35S:LBD17 and Pro35S:LBD18were 610, 700, 620 and 480, respectively. (F) Expression of LBD16 or LBD18 in recovered Pro35S:LBD16 or Pro35S:LBD18 transgenic seedlings with S, I or W phenotypes. The relative levels (log2) of LBD expression in LBD transgenic seedlings versus to that in control were shown as means ± SD from three biological replicates.

Although the recovered Pro35S:LBD transgenic seedlings could spontaneously form callus in their organs, the phenotypes and percentages of each category varied among the seedlings harboring different LBD genes. Overexpression of LBD17 or LBD29 was able to trigger callus formation in both root and shoot organs similar to that of LBD16, whereas the phenotypes were comparatively weaker (Figure 3A-3C). In contrast, overexpression of LBD18 only resulted in callused cotyledons (Figure 3D). On the other hand, overexpression of LBD16 or LBD29 led to more than 40% of the seedlings showing strong or intermediate phenotype, whereas only about 25% and 16% of seedlings could be categorized under the two categories among LBD17 and LBD18 transformants (Figure 3E), respectively. These observations suggest that the function of the four LBD members in callus formation is not completely redundant but differential for various organs.

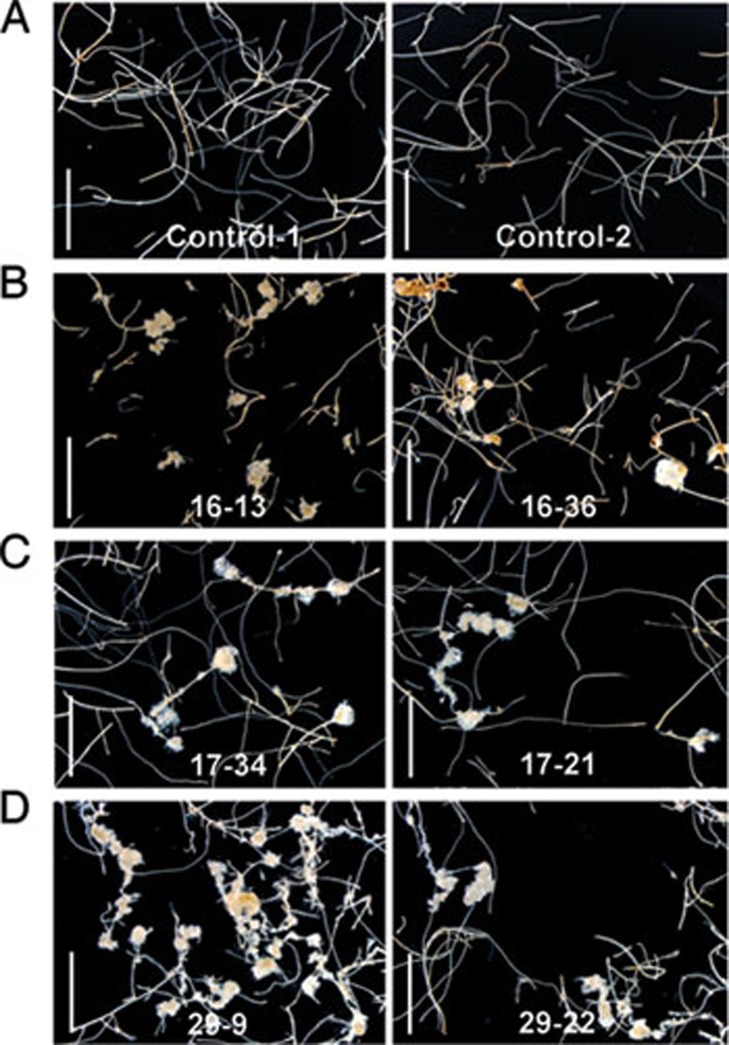

When grown in soil, the transgenic plants overexpressing different LBD genes exhibited a similar morphological defect with stunted organs, and only those with a relatively weak phenotype could produce T2 progenies (Supplementary information, Figure S1). Visible calluses were still formed in the root or hypocotyl of weak T2 LBD16, LBD17 and LBD29 transgenic plants (Supplementary information, Figure S2). We excised root fragments from these weak T2 plants and cultured them on medium without exogenous phytohormones, and surprisingly, some of the root explants from T2 progenies of LBD16, LBD17 or LBD29 transgenic plants could autonomously develop into calluses (Figure 4), confirming that ectopic expression of LBD genes is also sufficient to trigger callus formation in vitro.

Figure 4.

Ectopic expression of LBD genes promotes callus formation in vitro. (A-D) Morphology of root explants of control and weak Pro35S:LBD lines on B5 medium without exogenous phytohormones. The root explants of two independent T2 lines harboring an empty vector (Control-1, Control-2) (A), Pro35S:LBD16 (16-13, 16-36) (B), Pro35S:LBD17 (17-34, 17-21) (C) and Pro35S:LBD29 (29-9, 29-22) (D) were cultured on B5 hormone-free medium for 40 days. Bars = 5 mm.

To determine whether the ectopic expression of LBD may have simply influenced auxin biosynthesis in vivo, we used an auxin reporter system, DR5:GUS 37, to visualize the accumulation of endogenous auxin in Pro35S:LBD29 transgenic seedlings. Compared to that in control, GUS activity in Pro35S:LBD29 seedlings was not elevated (Supplementary information, Figure S3A), indicating that overexpression of LBD does not enhance auxin biosynthesis in vivo. Moreover, incubation of seedlings on the medium with aminoethoxyvinylglycine, a newly recognized auxin biosynthesis inhibitor 38, did not affect spontaneous callus formation in Pro35S:LBD29 transgenic plants (Supplementary information, Figure S3B). These results exclude the possibility that LBD-triggered callus formation is due to the changes in auxin biosynthesis or accumulation.

Suppression of LBD function inhibits callus formation

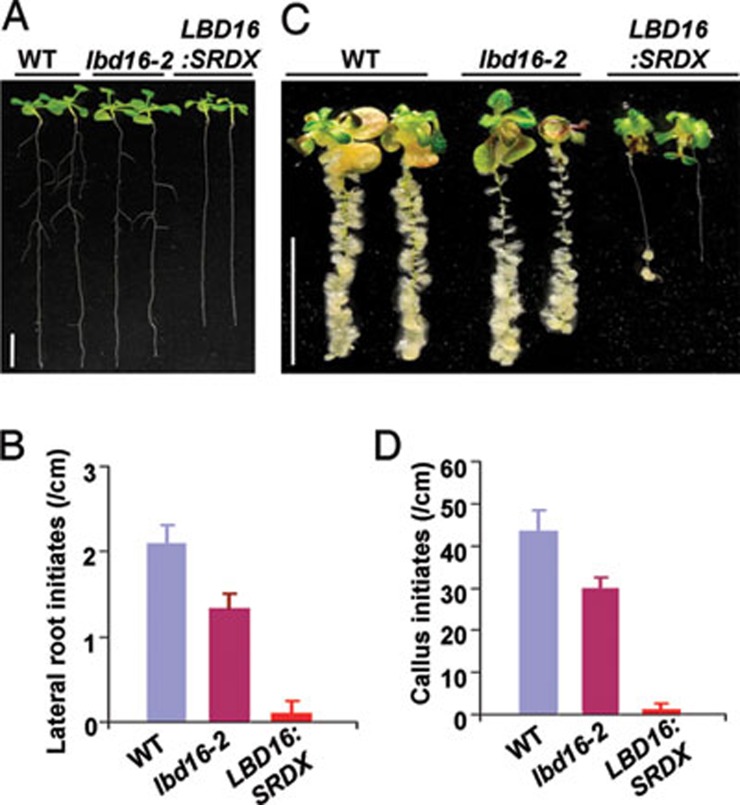

To further explore the function of LBD genes during callus formation, we obtained T-DNA insertion mutants, lbd16-2 and lbd18-1, two mutants that are publicly available among the four LBD genes. lbd18-1 is a null mutant of LBD18 gene (Supplementary information, Figure S4A and S4C) 27, and lbd18-1 seedlings did not show a distinguishable defect in lateral root initiation and CIM-induced callus formation (Supplementary information, Figure S5). By contrast, lbd16-2 seedlings had a reduced number of lateral roots (Figure 5A and 5B), and CIM-induced callus formation was apparently attenuated in lbd16-2 (Figure 5C and 5D). It should be noted that a low level of truncated LBD16 transcripts was expressed in lbd16-2 (Supplementary information, Figure S4A and S4B). To further overcome the functional redundancy of LBD members, we used a chimeric repressor-silencing technology 39 by expressing a LBD16:SRDX (SUPPERMAN repression domain) chimera under the control of CaMV 35S promoter, which converts the LBD16 transcriptional activator to a repressor that dominantly represses LBD function in transgenic plants 28. As expected, repression of LBD function dramatically blocked the lateral root initiation and CIM-induced callus formation in Pro35S:LBD16:SRDX transgenic seedlings (Figure 5A-5D). These results clearly demonstrate that LBD transcription factors are required for the auxin-induced callus formation program.

Figure 5.

Suppression of LBD function inhibits lateral root initiation and callus formation. (A) Morphology of nine-day-old wild type (WT), lbd16-2 and homozygous Pro35S:LBD16:SRDX (LBD16:SRDX) transgenic seedlings (from left to right). Bars = 10 mm. (B) Quantification of lateral root initiates on the primary roots of seedlings in A. The lateral root densities were shown as means ± SD (n = 10). (C) Callus-forming phenotype of WT, lbd16-2 and Pro35S:LBD16:SRDX seedlings on CIM. Five-day-old seedlings were incubated on CIM containing 0.2 μg/ml 2,4-D for 12 days. Bars = 10 mm. (D) Quantified callus initiates formed on the primary roots of seedlings in C. Callus initiates were examined with the seedlings on CIM for 5 days, and initiate densities were shown as means ± SD (n = 10).

Callus triggered by LBD resembles that induced by CIM

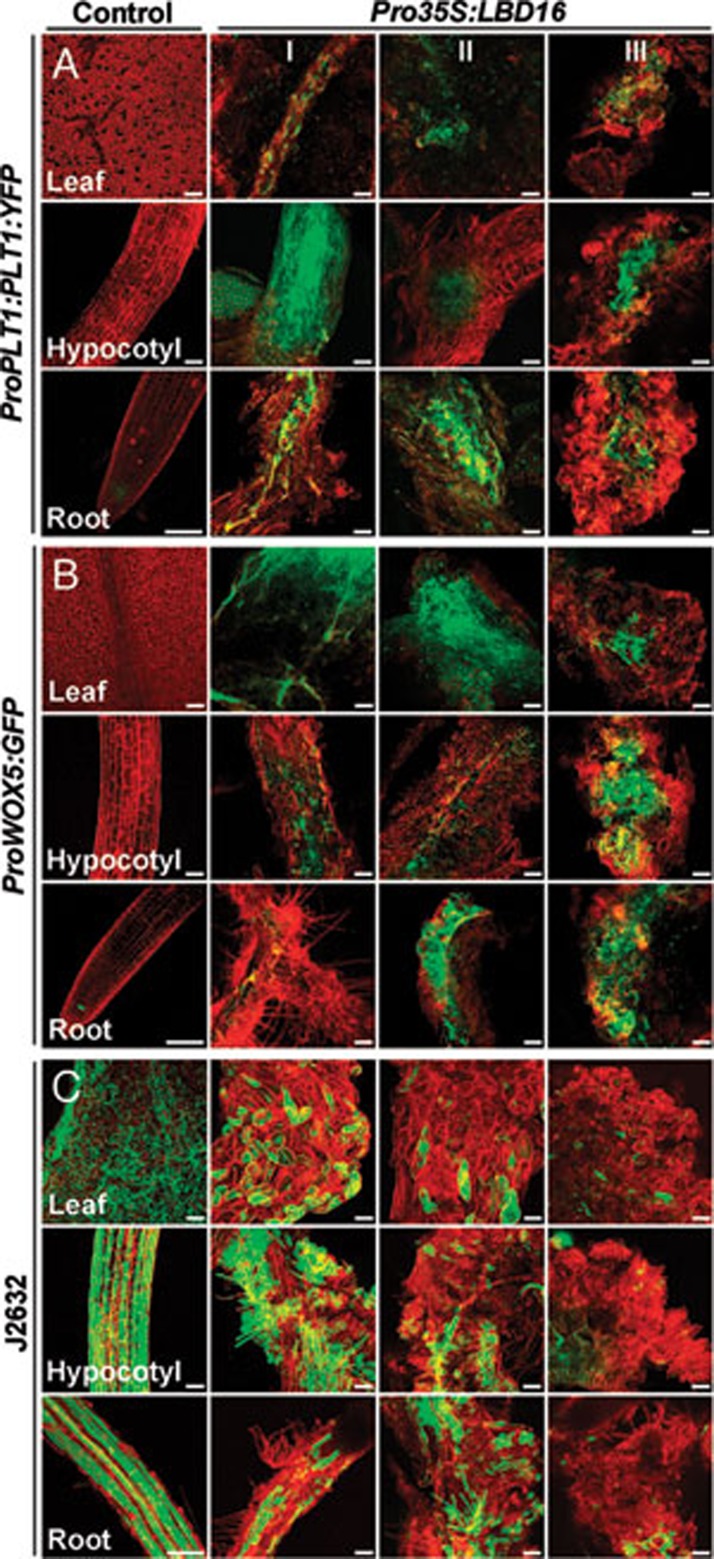

The callus derived from multiple organs on CIM resembles the tip of root meristem by enriched expression of root meristem genes 12, 14. To investigate the molecular property of the callus triggered by LBD genes, we examined the expression of three cell-type markers, ProPLT1:PLT1:YFP, ProWOX5:GFP and J2632, in T1 Pro35S:LBD16 and Pro35S:LBD29 transgenic seedlings, respectively. The expression of ProPLT1:PLT1:YFP, a marker specific for root stem cells 40, was confined only in the quiescent center (QC) and stem cells of root meristem in control seedlings (Figure 6A). However, the fluorescent signals were ectopically visualized in hypocotyl and vascular tissues of leaf and root in Pro35S:LBD16 seedlings (Figure 6A). Such signals were continuously observed when these organs developed into callused structures, and finally were present in the internal region of formed calluses (Figure 6A). Similarly, a dramatic activation of ProWOX5:GFP, a marker specific for root QC cells 41, was observed not only in leaf, hypocotyl and root but also in calluses derived from these organs in Pro35S:LBD16 transgenic seedlings (Figure 6B). By contrast, the signals of J2632, a marker for epidermis 42, declined gradually from all examined organs as callus formation occurred progressively (Figure 6C). Consistently, ectopic activation of ProPLT1:PLT1:YFP and ProWOX5:GFP was further observed in multiple organs and derived calluses in Pro35S:LBD29 seedlings (Supplementary information, Figure S6). These observations illustrate that LBD-triggered callus formation resembles callus induction on CIM by ectopic activation of the root development pathway.

Figure 6.

Root meristem genes are ectopically activated in Pro35S:LBD16 transgenic seedlings. (A) Expression of the root stem cell marker ProPLT1:PLT1:YFP in control and Pro35S:LBD16 seedlings. (B) Expression of the root QC marker ProWOX5:GFP in control and Pro35S:LBD16 seedlings. (C) Expression of the epidermal marker J2632 in control and Pro35S:LBD16 seedlings. The cell-specific marker lines without Pro35S:LBD16 construct were used as controls, and the cell marker signals (green) projected by confocal Z-stacks were overlaid with signals of organs stained with propidium iodide (red). I, II and III indicated organs at callus initiating, forming and growing stages, respectively. Bars = 100 μm.

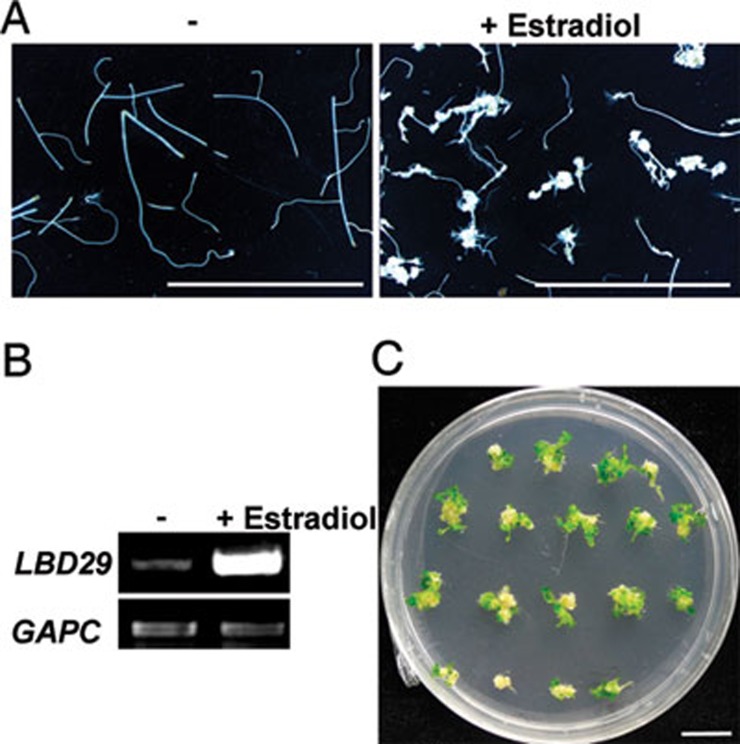

We further investigated the regeneration capability of the callus triggered by LBD using root explants of transgenic plants carrying a chemical-inducible OLexA-46 promoter:LBD29 (ProXVE:LBD29) 43. As expected, calluses were formed from the root explants when LBD29 expression was induced by 17-β-estradiol (Figure 7A and 7B). We then transferred the calluses to SIM, and found that shoot regeneration took place efficiently from these calluses derived from ProXVE:LBD29 root explants (Figure 7C), indicating that, similar to those induced by CIM, LBD-directed callus cells have acquired the pluripotency required for subsequent regeneration.

Figure 7.

LBD-directed callus has regeneration capacity on shoot inducing medium. (A) Callus-forming phenotype of root explants from ProXVE:LBD29 seedlings on the medium without (–) or with (+)17-β-estradiol. Root explants were cultured on the hormone-free B5 medium without or with 10 μM 17-β-estradiol for 50 days. (B) RT-PCR analysis of LBD29 expression in the root explants in A. (C) Shoot regeneration from calluses derived from ProXVE:LBD29 root explants. The calluses in A were transferred to shoot inducing medium (SIM) for 13 days and photographed. Bars = 5 mm.

LBD promotes callus formation downstream of ARFs

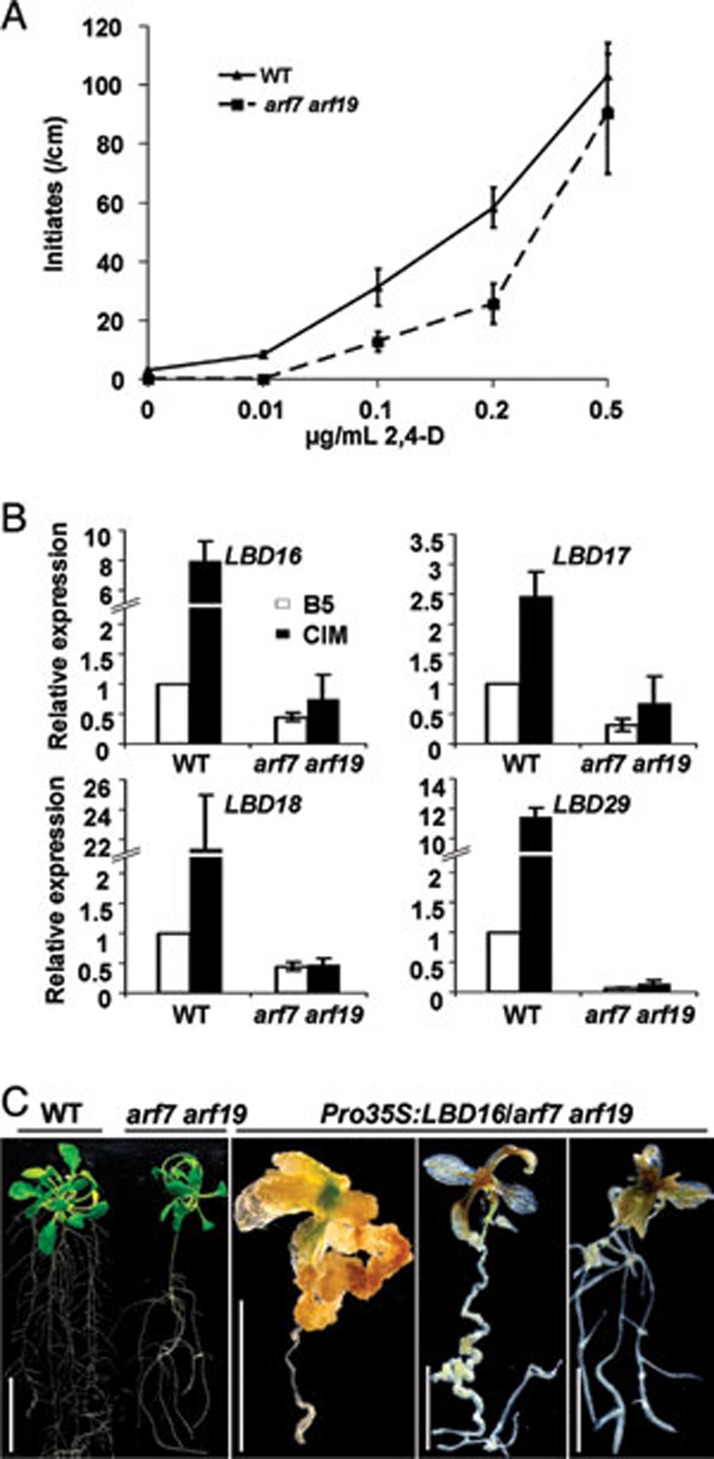

Recent work demonstrated that arf7 arf19 double knockout mutant was severely impaired in lateral root formation and that ARF7 and ARF19 regulated lateral root formation via direct activation of LBD16 and LBD29 28. To provide direct evidence that LBD-mediated callus formation is a part of the auxin signal cascades, we examined the callus-forming phenotype of arf7 arf19 on CIM. As shown in Figure 8A, arf7 arf19 seedlings displayed an impeded callus initiation on CIM with different concentrations of auxin. Further qRT-PCR analysis showed that the ectopic induction of LBD16, LBD17, LBD18 and LBD29 by CIM was dramatically attenuated or abolished in arf7 arf19 (Figure 8B), indicating that these LBD genes function, at least in part, downstream of ARF7 and ARF19 during callus induction. To further confirm this, we overexpressed LBD16 in arf7 arf19, and found that transgenic arf7 arf19 seedlings harboring Pro35S:LBD16 exhibited a varied degree of spontaneous callus initiation in multiple organs (Figure 8C). These observations demonstrate that the four LBD genes are targets of ARFs in directing callus formation.

Figure 8.

LBD acts downstream of ARFs in callus induction. (A) Callus initiation in primary roots of WT and arf7 arf19 seedlings on CIM. Seven-day-old seedlings were cultured on CIM containing indicated concentrations of 2,4-D for 5 days, and the callus initiate densities were shown as means ± SD (n = 12). (B) Expression of LBD16, LBD17, LBD18 and LBD29 in WT and arf7 arf19 seedlings on B5 or CIM. Seedlings were transferred to B5 or CIM medium containing 0.1 μg/ml 2,4-D for 48 h, and the relative expression levels of each LBD from three biological replicates were shown as means ± SD. (C) Spontaneous callus formation in arf7 arf19 seedlings overexpressing LBD16. Ten-day-old WT, arf7 arf19 and recovered Pro35S:LBD16/arf7 arf19 T1 seedlings were grown on hormone-free medium for 20 days. Bars = 20 mm in left panel, and 5 mm in other panels.

Discussion

LBD transcription factors are key regulators to mediate callus formation in plant regeneration

In a typical plant regeneration system, callus induction from explants is often required for the efficient regeneration of somatic embryos or new plants. Although recent studies suggested that the callus derived from multiple Arabidopsis organs was originated from pericycle or pericycle-like cells via a root development pathway 12, 14, the key regulators that govern callus formation remain elusive. Via a genome-scale transcriptome analysis, we identified that four LBD genes were rapidly and ectopically upregulated during the early stages of callus induction using both root and shoot explants. Further analyses revealed that these LBD genes were sufficient to and required for callus formation, and that LBD-directed calluses resembled those induced by CIM, characterized by ectopic activation of root meristem genes and regeneration capability (Figures 6 and 7). Although transgenic seedlings overexpressing each of these LBD genes could not fully recapitulate the callus-forming phenotype observed on CIM, it is likely that the ectopic expression of these LBD members induced by CIM is synergistically responsible for triggering the callus formation process in multiple organs. Furthermore, LBD16, LBD29 and LBD18 have been reported to be involved in the control of lateral root formation 27, 28, thus, our findings further strengthen the notion that callus formation is executed through the ectopic activation of a root development pathway 12, 14. Although the precise molecular mechanism remains unclear, our study clearly demonstrates that LBD transcription factors are key regulators in directing callus formation in a typical in vitro plant regeneration system. In addition, since the LBD family comprises a large number of members in plant genomes, it is likely that other close LBD homologues may also have some effect on callus formation, which might explain why transgenic plants overexpressing Arabidopsis LBD6/AS2 or poplar LBD1 displayed a slightly enhanced callus-forming phenotype 18, 26.

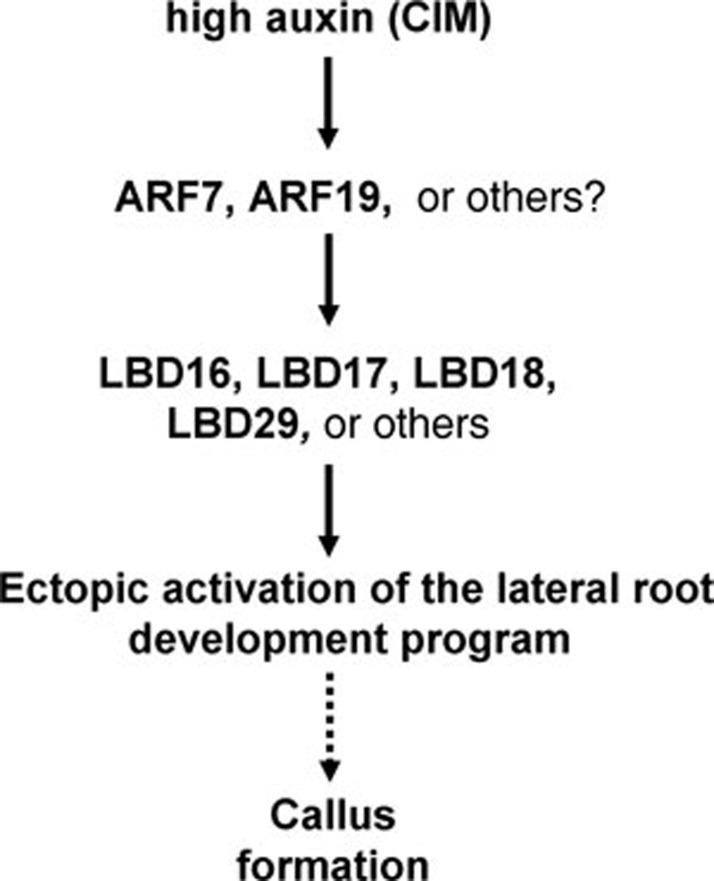

LBD links auxin signaling and callus induction program

Similar to that in Arabidopsis, the CIM used in other in vitro plant culture systems contains a high concentration of auxin, which has been shown to be crucial for callus induction 15. However, the molecular link between auxin signaling and callus formation has never been established. Here, the four LBD genes we identified are all auxin-responsive genes. Previous studies indicated that LBD16, LBD18 and LBD29 are direct or indirect targets of ARF7 and ARF19 to regulate lateral root formation 27, 28. Our analysis of arf7 arf19 double mutant further demonstrates that the four LBD genes are downstream of ARFs in directing callus formation process. Although other LBD homologues may also have an effect on the callus formation, the LBD genes downstream of ARFs obviously link auxin signaling to the callus formation program in a typical plant regeneration system (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

A proposed model for LBD-directed callus formation. Once the seedlings or explants are cultured on CIM, a high concentration of auxin in CIM constantly and ectopically induces the expression of LBD genes downstream of ARFs in multiple organs. The synergistically ectopic expression of these LBD genes triggers callus-forming program through the ectopic activation of root development pathway, thus conferring on cells the pluripotency for in vitro regeneration of new organs or whole plants.

Control of cell pluripotency in plants

In animals, the induction of pluripotent stem (iPS) cells is mediated by enforced expression of a few transcription factors, including Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog 44. Such ectopic expression of transcription factors leads to the reprogramming of somatic cells into iPS cells 45. However, counterparts of these transcription factors are not found in plant genomes, suggesting that the mechanism underlying the control of cell pluripotency in plants may differ from that in animals. In plants, callus induction is similar to the induction of iPS cells in animals because most of the callus cells are pluripotent. Our finding demonstrates that callus induction in plants is also modulated by ectopic expression of plant-specific LBD transcription factors. Consistent with this, the Arabidopsis WOUND-INDUCED DEDIFFERENTIATION 1, a member of plant-specific AP2/ERF transcription factor family, was recently identified to regulate the wound-induced cell dedifferentiation, a process during which similar calluses are formed in the wounded sites of explants 46. Therefore, despite evolutionary divergence of key regulators, transcriptional regulation seems to be a common mechanism underlying the control of formation of pluripotent cells in both kingdoms.

Surprisingly, AP2/ERF-mediated cell dedifferentiation was found not to follow the root development program 46, suggesting that there may be multiple pathways involved in the regulation of cell pluripotency in plants. It is likely that, in plants, different pathways may act to mediate different growth or environment stimuli to control cell pluripotency in a coordinative manner, thus conferring on plant tissues or cells a high regeneration capacity both in vivo and in vitro. This might also explain why the root explants of weak LBD transgenic seedlings could easily form callus without exogenous phytohormones. Finally, it is fascinating that the formation of a highly organized lateral root or unorganized calluses is dependent on the LBD abundance determined by a low- or high-auxin level. A future challenge is to elucidate different downstream molecular events triggered by different LBD levels, which would also help clarify whether callus induction in plants involves cell reprogramming as does the induction of iPS cells in mammals.

Materials and Methods

Plant growth and culture conditions

Seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana were germinated on 1/2 Murashige-Skoog (MS) medium (1/2 MS salts, 1% sucrose, 0.6% agar) at a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod at 22 ± 1 °C. For LBD expression analysis, seedlings or explants were transferred to the CIM (B5 medium supplemented with 0.5 μg/ml 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and 0.05 μg/ml kinetin) 5 for the times indicated. To observe the callus-forming phenotype in vivo and in vitro, LBD transgenic seedlings or their root explants harboring an empty vector or a Pro35S:LBD construct were grown on B5 medium without exogenous phytohormones. To investigate the regeneration capacity of callus induced by LBD, calluses were induced from root explants of ProXVE:LBD29 transgenic seedlings on the B5 medium with 10 μM 17-β-estradiol and subsequently transferred to SIM 5. To examine their sensitivity to auxin, lbd16-2 (SALK_040739), lbd18-1 (SALK_038125), arf7 arf19 and the homozygous Pro35S:LBD16:SRDX seedlings were cultured on CIM with varied concentrations of 2,4-D.

Microarray

Arabidopsis ATH1 GeneChips (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, USA) were used for gene expression profile analysis as described 6. Three independent biological replicates were performed at each time points. Affymetrix GeneChip Microarray Suite version 5.0 software was used to monitor the signals for individual genes, and background correction and normalization with the log2 scale RMA procedure were performed as described previously 47. The corrected P-value threshold was set to 0.05. The data set is available in the public repository Gene Expression Omnibus upon publication (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with the accession number GSE29543.

RNA isolation and gene expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated using a guanidine thiocyanate extraction buffer 48. qRT-PCR was performed with a Rotor-Gene 3000 thermocycler (Corbett Research, Sydney, Australia) with the SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II kit (Takara, Dalian, China), and all qRT-PCRs were carried out in three technical repeats and three biological replicates for each sample. The efficiency of amplification was assessed to the transcripts of ACTIN2. The relative expression values were calculated using a modified 2−ΔΔCT method 49. GUS activity was assayed with the method described previously 50. The primers used for gene expression analysis are listed in Supplementary information, Table S1.

Plasmid construction and Arabidopsis transformation

A 1.7-kb genomic DNA fragment of the LBD16 promoter upstream of start codon was amplified by PCR and cloned into pBI101 for generation of ProLBD16:GUS construct. The coding regions of LBD16, LBD17, LBD18 and LBD29 were cloned into pVIP96 50 for generation of Pro35S:LBD16, Pro35S:LBD17, Pro35S:LBD18 and Pro35S:LBD29 constructs, respectively, and a LBD16 fused with SRDX transcriptional repression domain (LDLDLELRLGFA) linker sequence 39 was used to generate Pro35S:LBD16:SRDX construct. The coding region of LBD29 was cloned into pER10 vector for generating ProXVE:LBD29 construct 43. All plasmids were introduced into Arabidopsis by Agrobacterium tumefaciens with a floral dip method 51. The primers used for plasmid constructions can be found in Supplementary information, Table S1.

Confocal microscopy

For confocal imaging, seedlings were stained lightly with propidium iodide (50 μg/ml), and immediately visualized under a confocal microscope. All images were taken under a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope. The propidium iodide fluorescence was excited at 593 nm and collected at 610-680 nm using a pinhole of 1 a.u., and GFP or YFP fluorescence was excited at 488 nm and collected at 495-550 nm with a pinhole setting of 2 a.u. using sequential scanning. All images were collected using a constant beam intensities and settings. The Z-stacks were reconstructed into a projection view with Zeiss LSM software, and at least 20 seedlings from each genotype were carefully imaged.

Accession numbers

The sequence data for the genes mentioned in this work can be found in Arabidopsis Genome Initiative as follows: LBD16 (At2g42430), LBD17 (At2g42440), LBD18 (At2g45420), LBD29 (At3g58190), ARF7 (At5g20730), ARF19 (At1g19220), WOX5 (At3g11260), PLT1 (At3g20840) and ACTIN2 (At3g18780).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to ABRC and Drs Ben Scheres (Utrecht University, Netherlands), Jim Haseloff (University of Cambridge, UK), Nam-Hai Chua (Rockefeller University, USA) for providing the seeds and constructs used in this study. This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2007CB948200) and by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30900108 and 30821007).

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Material

Morphology of transgenic plants overexpressing LBD genes.

Enhanced callus formation in weak Pro35S:LBD transgenic plants.

LBD-directed callus formation is not attributable to auxin biosynthesis.

Molecular characterization of Lateral root initiation and callus formation in lbd18-1. and lbd18-1.

Lateral root initiation and callus formation in lbd18-1.

Ectopic activation of root meristem genes in Pro35S:LBD29 transgenic seedlings.

Primers used in this study.

References

- Reinert J, Backs D. Control of totipotency in plant cells growing in vitro. Nature. 1968;220:1340–1341. doi: 10.1038/2201340a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe TA. History of plant tissue culture. Mol Biotechnol. 2007;37:169–180. doi: 10.1007/s12033-007-0031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoog F, Miller CO. Chemical regulation of growth and organ formation in plant tissues cultured in vitro. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1957;54:118–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum KD, Sánchez Alvarado A. Slicing across kingdoms: regeneration in plants and animals. Cell. 2008;132:697–710. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valvekens D, Montagu MV, Van Lijsebettens M. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana root explants by using kanamycin selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5536–5540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che P, Gingerich DJ, Lall S, Howell SH. Global and hormone-induced gene expression changes during shoot development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2002;14:2771–2785. doi: 10.1105/tpc.006668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson ML, Warnick DA. Competence and determination in the process of in vitro shoot organogenesis. Dev Biol. 1983;95:288–293. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che P, Lall S, Howell SH. Developmental steps in acquiring competence for shoot development in Arabidopsis tissue culture. Planta. 2007;226:1183–1194. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0565-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary AJ, Che P, Howell SH. Developmental events and shoot apical meristem gene expression patterns during shoot development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2002;32:867–877. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitteti BR, Peng Z. Proteome and phosphoproteome dynamic change during cell dedifferentiation in Arabidopsis. Proteomics. 2007;7:1473–1500. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitteti BR, Tan F, Mujahid H, Magee BG, Bridges SM, Peng Z. Comparative analysis of proteome differential regulation during cell dedifferentiation in Arabidopsis. Proteomics. 2008;8:4303–4316. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200701149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atta R, Laurens L, Boucheron-Dubuisson E, et al. Pluripotency of Arabidopsis xylem pericycle underlies shoot regeneration from root and hypocotyl explants grown in vitro. Plant J. 2009;57:626–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks GS. Shoot induction and organogenesis in vitro: a developmental perspective. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1994;30P:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto K, Jiao Y, Meyerowitz EM. Arabidopsis regeneration from multiple tissues occurs via a root development pathway. Dev Cell. 2010;18:463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon SP, Heisler MG, Reddy GV, Ohno C, Das P, Meyerowitz EM. Pattern formation during de novo assembly of the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Development. 2007;134:3539–3548. doi: 10.1242/dev.010298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husbands A, Bell EM, Shuai B, Smith HM, Springer PS. LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES defines a new family of DNA-binding transcription factors and can interact with specific bHLH proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:6663–6671. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majer C, Hochholdinger F. Defining the boundaries: structure and function of LOB domain proteins. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakawa H, Ueno Y, Semiarti E, et al. The ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana, required for formation of a symmetric flat leaf lamina, encodes a member of a novel family of proteins characterized by cysteine repeats and a leucine zipper. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43:467–478. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuai B, Reynaga-Peña CG, Springer PS. THE LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES gene defines a novel, plant-specific gene family. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:747–761. doi: 10.1104/pp.010926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Yu X, Wu P. Comparison and evolution analysis of two rice subspecies LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES domain gene family and their evolutionary characterization from Arabidopsis. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;39:248–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu QH, Guo AY, Gao G, et al. DPTF: a database of poplar transcription factors. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1307–1308. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida N, Townsley B, Chung KH, Sinha N. Regulation of SHOOT MERISTEMLESS genes via an upstream-conserved noncoding sequence coordinates leaf development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15953–15958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707577104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Xu Y, Dong A, et al. Novel as1 and as2 defects in leaf adaxial-abaxial polarity reveal the requirement for ASYMMETRIC LEAVES1 and 2 and ERECTA functions in specifying leaf adaxial identity. Development. 2003;130:4097–4107. doi: 10.1242/dev.00622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, Li Z, Zhu Y, et al. Arabidopsis genes AS1, AS2, and JAG negatively regulate boundary-specifying genes to promote sepal and petal development. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:566–575. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.113787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyano T, Thitamadee S, Machida Y, Chua NH. ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2-LIKE19/LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES DOMAIN30 and ASL20/LBD18 regulate tracheary element differentiation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20:3359–3373. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yordanov YS, Regan S, Busov V. Members of the LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES DOMAIN transcription factor family are involved in the regulation of secondary growth in Populus. Plant Cell. 2010;22:3662–3677. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.078634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HW, Kim NY, Lee DJ, Kim J. LBD18/ASL20 regulates lateral root formation in combination with LBD16/ASL18 downstream of ARF7 and ARF19 in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:1377–1389. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.143685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okushima Y, Fukaki H, Onoda M, Theologis A, Tasaka M. ARF7 and ARF19 regulate lateral root formation via direct activation of LBD/ASL genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:118–130. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inukai Y, Sakamoto T, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, et al. Crown rootless1, which is essential for crown root formation in rice, is a target of an AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR in auxin signaling. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1387–1396. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.030981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Wang S, Yu X, et al. ARL1, a LOB-domain protein required for adventitious root formation in rice. Plant J. 2005;43:47–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taramino G, Sauer M, Stauffer JL, et al. The maize (Zea mays L.) RTCS gene encodes a LOB domain protein that is a key regulator of embryonic seminal and post-embryonic shoot-borne root initiation. Plant J. 2007;50:649–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin G, Tohge T, Matsuda F, Saito K, Scheible WR. Members of the LBD family of transcription factors repress anthocyanin synthesis and affect additional nitrogen responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3567–3584. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.067041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albinsky D, Kusano M, Higuchi M, et al. Metabolomic screening applied to rice FOX Arabidopsis lines leads to the identification of a gene-changing nitrogen metabolism. Mol Plant. 2010;3:125–142. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura Y, Iwakawa H, Machida Y, Machida C. Characterization of genes in the ASYMMETRIC LEAVES2/LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES (AS2/LOB) family in Arabidopsis thaliana, and functional and molecular comparisons between AS2 and other family members. Plant J. 2009;58:525–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplaze L, Parizot B, Baker A, et al. GAL4-GFP enhancer trap lines for genetic manipulation of lateral root development in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot. 2005;56:2433–2442. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okushima Y, Overvoorde PJ, Arima K, et al. Functional genomic analysis of the AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR gene family members in Arabidopsis thaliana: unique and overlapping functions of ARF7 and ARF19. Plant Cell. 2005;17:444–463. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.028316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov T, Murfett J, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ. Aux/IAA proteins repress expression of reporter genes containing natural and highly active synthetic auxin response elements. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1963–1971. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.11.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soeno K, Goda H, Ishii T, et al. Auxin biosynthesis inhibitors, identified by a genomics-based approach, provide insights into auxin biosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51:524–536. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratsu K, Matsui K, Koyama T, Ohme-Takagi M. Dominant repression of target genes by chimeric repressors that include the EAR motif, a repression domain, in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2003;34:733–739. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aida M, Beis D, Heidstra R, et al. The PLETHORA genes mediate patterning of the Arabidopsis root stem cell niche. Cell. 2004;119:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haecker A, Gross-Hardt R, Geiges B, et al. Expression dynamics of WOX genes mark cell fate decisions during early embryonic patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 2004;131:657–668. doi: 10.1242/dev.00963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engineer CB, Fitzsimmons KC, Schmuke JJ, Dotson SB, Kranz RG. Development and evaluation of a Gal4-mediated LUC/GFP/GUS enhancer trap system in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2005;5:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo J, Niu QW, Frugis G, Chua NH. The WUSCHEL gene promotes vegetative-to-embryonic transition in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2002;30:349–359. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng HH, Surani MA. The transcriptional and signaling networks of pluripotency. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:490–496. doi: 10.1038/ncb0511-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwase A, Mitsuda N, Koyama T, et al. The AP2/ERF transcription factor WIND1 controls cell dedifferentiation in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol. 2011;21:508–514. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Bao F, Li J. Promotive effect of brassinosteroids on cell division involves a distinct CycD3-induction pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2000;24:693–701. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Xie Q, Chua NH. The Arabidopsis auxin-inducible gene ARGOS controls lateral organ size. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1951–1961. doi: 10.1105/tpc.013557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Morphology of transgenic plants overexpressing LBD genes.

Enhanced callus formation in weak Pro35S:LBD transgenic plants.

LBD-directed callus formation is not attributable to auxin biosynthesis.

Molecular characterization of Lateral root initiation and callus formation in lbd18-1. and lbd18-1.

Lateral root initiation and callus formation in lbd18-1.

Ectopic activation of root meristem genes in Pro35S:LBD29 transgenic seedlings.

Primers used in this study.