Abstract

The seroprevalence of Entamoeba histolytica infection in the residents of seven provinces in China was examined by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with a crude antigen and a recombinant surface antigen, C-Igl, of the parasites. A total of 1,312 serum samples were investigated. The positivity rates for these two antigens were 11.05% and 6.25%, respectively. There was no significant difference in the seropositivity to E. histolytica between men and women. We used a logistic regression model and maximal-likelihood methods to estimate the prevalence of E. histolytica infection from sequential serologic data. Seropositivity in Sichuan, Guizhou, and Sinkiang Provinces was higher than that in Beijing, Shanghai, and Qinghai Provinces. The present study provides an overview of seropositivity to E. histolytica infection in seven provinces in China and use the logistic regression model estimation method to achieve a more accurate measure of amebiasis incidence.

Introduction

Amebiasis is an infection caused by the protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica.1 Amebiasis is a major human gastrointestinal infection affecting approximately 50 million persons worldwide and accounts for more than 100,000 deaths annually.2,3 Another intestinal ameba, E. dispar, is morphologically indistinguishable from E. histolytica, but is nonpathogenic.4 Entamoeba histolytica is unique among amebae because of its ability to disrupt the intestinal mucosa, causing intestinal disease, amebic colitis, and the capacity for further hematogenous spread, thereby producing potentially fatal abscesses and extraintestinal diseases.2,4,5

Amebiasis is a common problem in developing countries.6 The infection is initiated when mature cysts are ingested by hosts.7 Amebiasis is extremely transmissible, with an infectious dose as low as one viable cyst, and is usually acquired from food or water sources contaminated with feces.8 The prevalence rate of this disease is up to 6% in areas that have poor sanitation.9 For example, in a rural community in Mexico, 13.8% of the total population was shown to have asymptomatic E. histolytica infection by a polymerase chain reaction. Furthermore, a high rate of asymptomatic infection (21.4%) was detected fecal samples of persons from Africa and Egypt by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).10,11 The infection patterns differ between developing and developed countries. In the United States and Australia, persons at risk for E. histolytica infection include immigrants, travelers returning from countries with high endemicity, indigenous persons, and men who have sex with men.12,13

However, no data on E. histolytica infection in China are available, except for information on fecal examinations obtained during the first national survey of human parasites in 1992.14 Therefore, the current preliminary study was conducted to estimate the seroprevalence of E. histolytica infection in a population in China. The known symptoms of E. histolytica infection include diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever. Estimates show that in 90% of human cases, the infection is self-limiting and asymptomatic.15x However, positive serologic results are found in most asymptomatic cases infected with E. histolytica; thus, serologic tests are also applicable.16 Serodiagnosis is an important laboratory diagnostic tool for amebiasis, as well as for microscopic detection of pathogens.

Recently, several recombinant E. histolytica antigens have been prepared, and their usefulness for serodiagnosis has been reported.17–19 One of these useful antigens is the glycosylphosphatidylinisotol-anchored 150-kD intermediate subunit (Igl) of galactose- and n-acetyl-D-galactosamine-inhibitable lectin. Recombinant Igl is well recognized in serum samples from patients with amebiasis, but not from patients with other protozoan infections. The C-terminus fragment of Igl is valuable for serodiagnosis of amebiasis.19 In the present study, antibodies against E. histolytica were examined by ELISA using crude E. histolytica antigen and the recombinant fragment of the C-terminus fragment of Igl (C-Igl) of E. histolytica. A total of 1,312 serum samples collected from seven provinces in China had been examined.

Materials And Methods

Ethical considerations.

The serum samples were provided by the National Institute of Parasitic Diseases, Chinese Center of Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC). The CCDC obtained and stored the serum samples from donors during the survey organized and conducted by the Chinese Ministry of Health during 2001–2004. Simple random sampling was conducted to select participants. The Medical Ethics Committee of Fudan University approved the use of the serum samples in the current study, and written informed consent was obtained from the donors. All samples were from rural or urban–rural-integration areas.

Materials.

The serum samples were provided by the National Institute of Parasitic Diseases, CCDC. Crude antigen was prepared from the trophozoites of E. histolytica strain HK9 axenically cultured in a BI-S-33 medium.20 After three washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the trophozoites were suspended in a 1:10 PBS solution, sonicated, and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 30 minutes. The supernate was used as crude antigen to detect antibodies against E. histolytica.19

Methods.

The DNA fragment-coding C terminus of an intermediate subunit of galactose- and n-acetyl-D-galactosamine-inhibitable lectin (C-Igl)21–24 was amplified by using PCR. The oligonucleotide primers used were19 EhIgl-S603: 5′-CCCTCGAGGAAGGACCAAATGCAGAAGAT-3′ and EhIgl-AS1088: 5′-CCCTCGAGTTAAATGCCTTTAGCTCCATT-3′. The DNA fragment coding C-Igl was ligated into the expression vector pET19-b. The plasmid with a correct insert direction was transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21 Star (DE3) pLysS and induced with 1 mM isopropylthiogalactoside for protein expression in Luria–Bertani medium. The recombinant C-Igl protein was harvested as an inclusion body and purified for detecting antibodies against E. histolytica.

The ELISA was performed with serum samples in 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plates (Greiner Bio One, Frickenhausen, Germany) in duplicate. The wells of the ELISA plates containing 5 μg of crude antigen or 100 ng of recombinant C-Igl diluted with coating buffer (0.01 M Na2CO3, 0.035 M NaHCO3, pH 9.6), were incubated overnight at 4°C in a moist chamber. The plates were washed with PBS-Tween and then treated with PBS containing 1% skimmed milk for 1 hour. A total of 100 μL of serum samples diluted to 1:400 with PBS were added to the wells and incubated for 1 hr at room temperature. After washing with PBS-Tween, the wells were incubated with 100 μL of horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-human IgG (diluted to 1:1,000 with 1% skimmed milk; MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) for 1 hour at room temperature. After subsequent washing with PBS-Tween, the wells were incubated with 200 μL of substrate solution (0.4 mg/mL of o-phenylenediamine in citric acid–phosphate buffer, pH 5.0, containing 0.001% hydrogen peroxide) for 30 minutes. The reaction was halted by the addition of 50 μL of 2.5 M H2SO4. The optical density at 490 nm was recorded by using an ELX800 universal microplate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT). The cut-off point for a positive result was defined as an optical density at 490 nm > 3 SD above the mean positivity rates for healthy controls.

Statistical analysis.

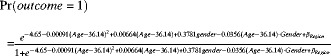

Statistical analysis was performed by using SAS software version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The chi square test was first used to test the independence of sex, region, and age category for every 10 years of age. A logistic regression model with a general form was applied, and the probability (Pr) was calculated according to the equation

where y = 1 if the serum had a positive result in the C-Igl/crude antigen test, and y = 0 if the serum had a negative result.25 The association between each variable and each outcome was explored by means of multivariate logistic regression modeling, with visual inspection acting as an auxiliary. The model building procedure incorporates the stepwise forward selection method. The main effect of variables that we were interested in remained in the model. High order effect of continuous variables and interaction terms were added according to the significance of likelihood ratio tests on the condition that marginality restrictions were observed to construct hierarchical models. Overall, a value P < 0.05 was considered statistical significant. Age was treated as a continuous variable in logistic regression models, and was mean centered to avoid multicollinearity caused by its high order effects. The C-Igl and crude antigen tests were regarded as two separate experimental tests. Thus, the same analysis was applied to both tests.

Results

The ELISA reactivity to E. histolytica target antigens from residents of seven provinces in China is shown in Table 1. The age of the study participants ranged from 0 to 85 years (mean ± SD age = 36.14 ± 16.35 years). For 678 males and 634 females, mean ± SD age values were 35.83 ± 16.70 and 36.47 ± 15.98 years, respectively. In Table 1, the total positivity rate of the C-Igl test was 6.25% (5.31% for males and 7.26% for females). However, the difference between the values was not significant. Average C-Igl positivity rates of females and males in every age group and the mean C-Igl positivity rates of serum samples in the different provinces are also shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients tested for C-Igl and crude antigens of Entamoeba histolytica in China

| Characteristic | No. tested | No. (%) positive for C-Igl | No. (%) positive for crude antigens | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1,312 | 82 (6.25) | 145 (11.05) | |

| Sex | NS (0.023) | |||

| M | 678 | 36 (5.31) | 62 (9.14) | |

| F | 634 | 46 (7.26) | 83 (13.09) | |

| Age, years | NS (0.002) | |||

| ≤ 10 | 72 | 3 (4.17) | 4 (5.56) | |

| 11–20 | 154 | 5 (3.25) | 16 (10.39) | |

| 21–30 | 286 | 24 (8.39) | 48 (16.78) | |

| 31–40 | 318 | 25 (7.86) | 42 (13.21) | |

| 41–50 | 216 | 13 (6.02) | 20 (9.26) | |

| 51–60 | 148 | 9 (6.08) | 9 (6.08) | |

| 61–70 | 93 | 3 (3.23) | 6 (6.45) | |

| > 70 | 25 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Province | < 0.001 | |||

| Beijing | 188 | 2 (1.05) | 12 (6.38) | |

| Shanghai | 130 | 5 (3.85) | 9 (6.92) | |

| Sichuan | 142 | 10 (7.04) | 22 (15.49) | |

| Guangxi | 189 | 6 (3.17) | 18 (9.52) | |

| Guizhou | 285 | 41 (14.39) | 50 (17.54) | |

| Qinghai | 190 | 1 (0.53) | 5 (2.63) | |

| Sinkiang | 188 | 17 (9.04) | 29 (15.43) |

Based on chi-square test for homogeneity. NS = not significant.

The positivity rates of the crude antigen test were 11.05% for the total sample, 9.14% for the males, and 13.09% for the females. Sex, age, and province were all significant risk factors in the crude antigen test. In general, the samples from females 11–20 and 21–30 years of age in the provinces of Sichuan, Guizhou, and Sinkiang were more likely to be positive in the C-Igl and the crude antigen tests.

The age groups 21–30 and 31–40 years of age had the highest positivity rates, and age groups 41–50 and 51–60 years of age also had higher positivity rates than the other groups, but the differences in comparison of those of other age groups were not significant.

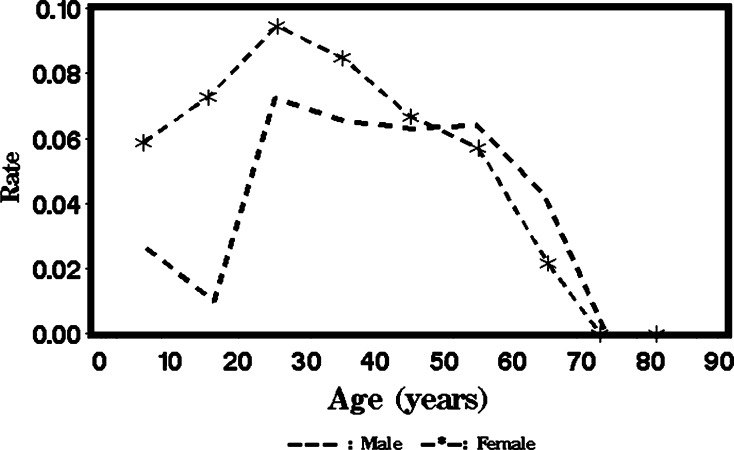

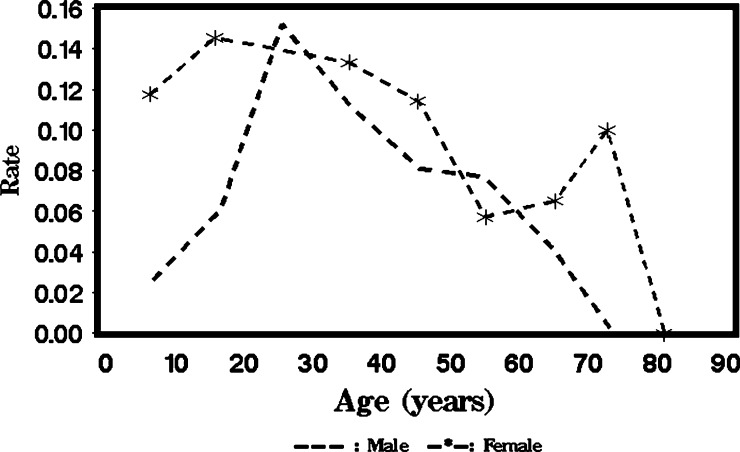

We grouped persons by an age of every 10 years and plotted the positivity rate against the midpoint age of each group for C-Igl (Figure 1 ) and for crude antigen (Figure 2 ). For males and females, the positivity rate of the C-Igl test increased with age until an age of 25 years and then decreased with age (Figure 1). A linear age effect is probably inadequate to capture this trend. Thus, it is reasonable to perform a formal statistical test for the quadratic term or even higher order effect for age. Meanwhile, at young ages, a higher positivity rate for C-Igl seems to be related to females compared with males. Nevertheless, the difference tends to decrease with age, and at ages > 50 years, the positivity rate for the C-Igl test was slightly higher in males than in females. This pattern suggests that an interaction might exist and prompts statistical testing on interaction terms between age and sex effects. Similar features justify testing a high-order age effect and interaction terms for crude antigen tests (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Mean positive seroprevalence rates for C-Igl of Entamoeba histolytica in China in each age group for males versus females.

Figure 2.

Mean positive seroprevalence rates for crude antigen of Entamoeba histolytica in China in each age group for males versus females.

The stepwise model building procedure starts from the simplest model. The main effect of age, sex, and region remained in the model regardless of statistical significance because these three variables are of study interest. When the quadratic age effect was added, at one degree of freedom, the deviance of model decreased 3.9432 for C-Igl and 6.5968 for crude antigen. Likelihood ratio tests suggest that the quadratic term of age has significant effect on C-Igl (P = 0.047061) and crude antigen P = 0.010216). Furthermore, adding an age × sex interaction led to a reduction of deviance at one degree of freedom (4.2765 for C-Igl and 1.7491 for crude antigen). Likelihood ratio tests detected a significant age × sex interaction on C-Igl (P = 0.038642) but not on crude antigen (P = 0.18599). No interaction involving region or the sex gender × age × age interaction was shown to be significant by using likelihood ratio tests. The final model for C-Igl (Table 2) contains the quadratic age effect and age × sex interaction and the main effect of age, sex, and region. The final model for crude antigen (Table 2) includes the same effects except for the age × sex interaction. Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit tests demonstrated that either model fits the data well, (P = 0.9499 for C-Igl and 0.8395 for crude antigen (Table 2, Supplemental Table 1, and Supplemental Table 2).

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis of seroprevalence of C-Igl and crude antigens of Entamoeba histolytica in China*

| Characteristic | Coefficient ± SE | Odds ratio | 95%% Confidence interval | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −4.6511 ± 0.7301 (−2.8522 ± 0.3238) | < 0.0001 (< 0.0001) | ||

| Age × age | −0.00091 ± 0.000462 (−0.00083 ± 0.000346) | 0.0482 (0.0158) | ||

| Age × sex | −0.0356 ± 0.0176 | 0.0431 | ||

| Age | 0.00664 ± 0.0124 (−0.0180 ± 0.00654) | 0.5908 (0.0060) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| F vs. M | 0.3781 ± 0.2421 (0.4487 ± 0.1840) | 1.566 | (1.092–2.247) | 0.1184 (0.0147) |

| Region† | ||||

| Guangxi vs. Beijing | 1.2904 ± 0.8294 (0.5881 ± 0.3960) | 3.634 (1.800) | 0.715–18.466 (0.829–3.912) | 0.1197 (0.1375) |

| Guizhou vs. Beijing | 2.9080 ± 0.7337 (1.2867 ± 0.3405) | 18.319 (3.621) | 4.349–77.160 (1.858–7.058) | < 0.0001 (0.0002) |

| Qinghai vs. Beijing | −0.7141 ± 1.2309 (−0.9269 ± 0.5453) | 0.490 (0.396) | 0.044–5.466 (0.136–1.152) | 0.5618 (0.0892) |

| Shanghai vs. Beijing | 1.4361 ± 0.8492 (0.2528 ± 0.4615) | 4.204 (1.288) | 0.796–22.208 (0.521–3.181) | 0.0908 (0.5839) |

| Sichuan vs. Beijing | 1.9645 ± 0.7854 (1.0418 ± 0.3817) | 7.131 (2.834) | 1.530–33.246 (1.341–5.989) | 0.0124 (0.0063) |

| Sinkiang vs. Beijing | 2.3298 ± 0.7574 (1.0952 ± 0.3643) | 10.276 (2.990) | 2.329–45.344 (1.464–6.105) | 0.0021 (0.0026) |

Values in parentheses are those for crude antigens.

Beijing was used as the referent.

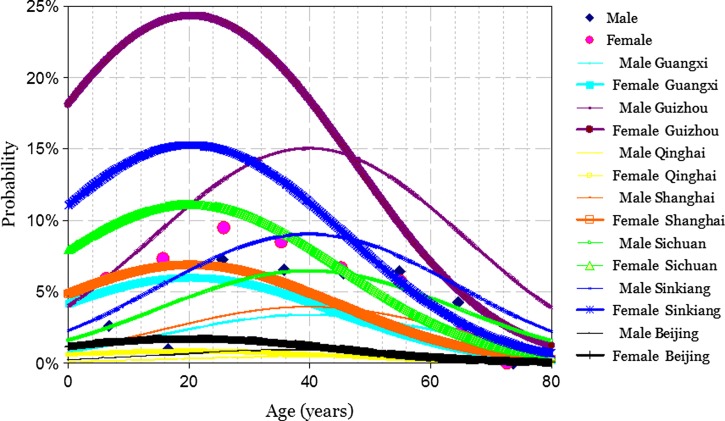

In the logistic regression model for the C-Igl outcome, the dependent variable was the binary variable (1 = positive and 0 = negative outcome for the C-Igl test). The independent variables included the binary variable sex (1 = female and 0 = male), mean-centered age, square of mean-centered age, the interaction term of sex and age, and the six-level categorical variable region. The probability of a positive outcome of C-Igl test is shown in Figure 3 and was calculated according to the equation

|

Figure 3.

Probability of positive C-Igl test result for Entamoeba histolytica in China predicted by the model used.

where βRegion = 1.29 for Guangxi, 2.91 for Guizhou, −0.71 for Qinghai, 1.43 for Shanghai, 1.96 for Sichuan, 2.33 for Sinkiang, and 0 for Beijing.

For persons of the same sex and the same age, the probability of a positive outcome of the C-Igl test is significantly higher in Guizhou, Sinkiang, and Sichuan than in Beijing (odds ratios = 18.32, 10.28 and 7.13, respectively), but Guangxi, Qinghai, and Shanghai did not have significant difference compared with Beijing. The odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are shown in Table 2.

A significant interaction between age and sex effect implies that the odds ratio of a positive result of the C-Igl test between males and females varies with age. Thus, the odds ratio of sex must be estimated with the presence of age. The estimated log odds ratio of a female versus a male from the same region at the age of a years was ln[odds ratio (sex = 1 versus sex = 0, age = a)] = 0.3781 − 0.0356a. The estimator of variance was var{ln[odds ratio(sex = 1 versus sex = 0, age = a)]} = 0.0586088 + 0.003089a2 + 2a(−0.00155), where 0.0586088 is the variance of the sex coefficient, 0.03089 is the variance of age × sex interaction coefficient, and −0.00155 is the covariance of the age and age × sex term. By calculating the endpoints as

and then exponentiating them, the odds ratios and the 95% confidence intervals were obtained. Odds ratios and the 95% confidence intervals calculated for a female versus a male from the same region at the ages of 5, 10, 15, 20, …, 80 years are shown in Table 3. From a younger age to 33 years of age, females have higher rates of positive results for the C-Igl test, and the difference was statistically significant (odds ratios = 1.63–4.42) Among persons > 33 years of age, the difference between males and females loses statistical significance with regard to the C-Igl test. When age is greater than a value between 45 and 50 years, the model suggests a higher probability of positive C-Igl results among males than among females from the same region. However, the difference lacked statistic significance.

Table 3.

Estimated odds ratio of females versus males for a positive result for C-Igl antigen of Entamoeba histolytica in China, controlling for age

| Age, years | Odds ratio | SE | 95% Confidence interval | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 4.4155 | 2.5800 | 1.4048–13.8786 | 0.0110 |

| 10 | 3.6965 | 1.8689 | 1.3722–9.9574 | 0.0097 |

| 15 | 3.0945 | 1.3320 | 1.3310–7.1942 | 0.0087 |

| 20 | 2.5905 | 0.9354 | 1.2765–5.2572 | 0.0084 |

| 25 | 2.1687 | 0.6540 | 1.2009–3.9164 | 0.0103 |

| 30 | 1.8155 | 0.4697 | 1.0933–3.0146 | 0.0212 |

| 35 | 1.5198 | 0.3673 | 0.9465–2.4406 | 0.0832 |

| 40 | 1.2723 | 0.3251 | 0.7711–2.0994 | 0.3459 |

| 45 | 1.0651 | 0.3153 | 0.5962–1.9027 | 0.8313 |

| 50 | 0.8917 | 0.3158 | 0.4454–1.7851 | 0.7461 |

| 55 | 0.7464 | 0.3155 | 0.3260–1.7092 | 0.4890 |

| 60 | 0.6249 | 0.3108 | 0.2358–1.6563 | 0.3445 |

| 65 | 0.5231 | 0.3012 | 0.1692–1.6169 | 0.2604 |

| 70 | 0.4379 | 0.2875 | 0.1209–1.5859 | 0.2085 |

| 75 | 0.3666 | 0.2709 | 0.0861–1.5604 | 0.1745 |

| 80 | 0.3069 | 0.2524 | 0.0612–1.5387 | 0.1510 |

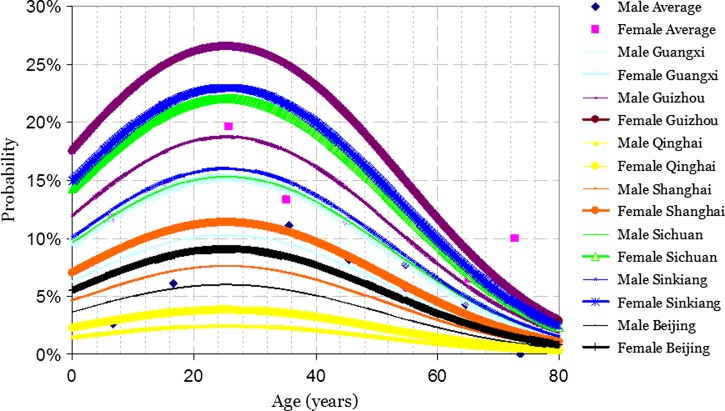

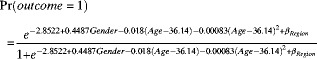

Similarly, a logistic regression model using the outcome of the crude antigen test as the dependent variable was developed (Table 2). This model also included the square of adjusted age. The probability of a positive outcome for the crude antigen test, which is shown in Figure 4, was calculated by using the function obtained from the final logistic regression model

|

Figure 4.

Probability of positive crude antigen test result for Entamoeba histolytica in China predicted by model used.

where βRegion = 0.5881 for Guangxi, 1.2867 for Guizhou, −0.9269 for Qinghai, 0.2528 for Shanghai, 1.0418 for Sichuan, 1.0952 for Sinkiang, and 0 for Beijing.

Comparing persons of the same sex and the same age showed that Guizhou, Sinkiang, and Sichuan differed significantly from Beijing (odds ratios = 3.62, 2.99, and 2.834. respectively). Among persons at the same age from the same region, the odds ratio of a female versus a male was 1.57 for a positive result for the crude antigen test (P = 0.0147). The 95% confidence intervals are shown in Table 2.

Discussion

Although infection with E. histolytica has a worldwide distribution and is common in persons in tropical and subtropical areas of developing countries, it often results in serious medical and socioeconomic problems. However, this protozoan infection does not have a high incidence in China,14 and all data for direct microscopy of fecal samples suggest that E. histolytica infection may be endemic to rural areas of China.26,27 Furthermore, the present prevalence of E. histolytica infection in China is not known.

From a public health perspective, obtaining epidemiologic data on E. histolytica infection in China is important. An overview on the incidence of E. histolytica infection in China could help predict future effects of E. histolytica infection on health care resources, as well as provide opportunities for evaluating the interventions. The use of serologic data to estimate the incidence of infection requires an antibody assay that is sensitive and specific for recent E. histolytica infections. If there were sequential serologic data for E. histolytica infections, the method described in the current study could be used to estimate the incidence. Because E. histolytica is morphologically indistinguishable from E. dispar,28–31 an ELISA was used to investigate the seroprevalence of E. histolytica infections.

Several commercial kits using crude antigen are now available for serodiagnosis of amebiasis, and recombinant C-Igl has a higher specificity than that described in our previous study.19 Another advantage of the recombinant protein is that the use of defined proteins in serodiagnosis facilitates standardization of the assays. Moreover, production of large quantities of recombinant C-Igl may be an economically effective alternative to ameba trophozoite cultivation.32 Therefore, we strongly recommend the use of recombinant C-Igl rather than crude antigen in serodiagnosis.

In the present study, C-Igl, a recombinant antigen, was selected as the diagnostic antigen, in addition to crude antigen. We studied 1,312 serum samples from seven provinces in China. The positivity rates for C-Igl determined by using an ELISA were 1.06% (2 of 188) for Beijing, 3.85% (5 of 130) for Shanghai, 7.04% (10 of 142) for Sichuan, 3.17% (6 of 189) for Guangxi, 14.39% (41 of 285) for Guizhou, 0.53% (1 of 190) for Qinghai, and 9.04% (17 of 188) for Sinkiang. However, the prevalence rates of E. histolytica/E. dispar infection obtained using the direct microscopy of fecal samples in Beijing, Shanghai, Sichuan, Guangxi, Guizhou, Qinghai, and Sinkiang provinces were 0.29%, 0.008%, 0.84%, 1.5%, 2.25%, 0.48%, and 2.4%, respectively.14 Because microscopy has low sensitivity and specificity for detection of amebiasis, these prevalence rates might be underestimates.

Conversely, because the serosurvey detected a sustained antibody response that persisted even after the infection,33,34 it contributed to the higher prevalence of infection in the present study compared with that in the 1992 survey. The seroprevalence we found in the current study provides an overview of E. histolytica infection in China, but does provide information on the incidence of amebiasis. The ELISA using serum samples showed a relatively low positivity rate for E. histolytica infection in Beijing, Shanghai, and Qinghai. Such findings were reasonable for Beijing and Shanghai because of their better sanitation infrastructure and health education programs. In Qinghai Province, the low temperature and dry air are not suitable for survival of E. histolytica cysts.35,36 Higher positivity rates were obtained in Sichuan, Guizhou, and Sinkiang Provinces because of their hygiene and environmental conditions.

Higher seropositivity rates (Table 1) and lower odds ratios (Table 2) were observed when crude antigen was used. The seropositivity rate in ELISA using the crude antigen was higher than that in ELISA using C-Igl. This result can be attributed to the lower specificity of crude antigen, as reported.19,35

The age groups 21–30, 31–40, 41–50 and 51–60 years had higher positivity rates, but the differences when compared with other age groups were not significant. This finding could be caused by their higher populations compared with those of other age groups, or by the fact that persons 21–60 years of age have more social activities and greater opportunity for exposure to E. histolytica. The results also indicated that females have higher seropositivity rates than males (Table 1), which is further represented in the odds ratios shown in Table 2. However, no statistical differences were detected. To our knowledge, there is no sex difference for intestinal amebiasis. However, amebic liver abscess is 3–10 times more common in males.36 The reason for the higher seropositivity of the female population is unclear.

The logistic regression model indicates the presence of some residual spatial autocorrelations after accounting for covariate effects, indicating that the variables used in the models did not capture all spatial variations in the observations.37,38 The logistic regression model described in the present study facilitates generation of incidence data through the novel application of likelihood-based estimation to the analysis of sequential serologic data without any clinical information. The logistic regression model can be used to assess the infection probability of a serum sample, provided the age, sex, and province of the patient are known. However, without any information concerning clinical symptoms, related diseases, or individual customs, predicting the probability of a positive result on the basis of general background information alone is inappropriate. Therefore, the model could only be used for the analyses of a few risk factors. The potential use of this model for incidence is not supported by the data from our study.

The use of serologic data to estimate the incidence of infection requires an antibody assay that is sensitive and specific for recent infection. Otherwise, estimation of the infection rate by using clinical surveillance data would be difficult until epidemic peaks are observed. The logistic regression model in this report paper provides an improved tool for estimating incidence. The model can be continuously optimized. For instance, if a new serum sample or updated background information of patients is obtained, some coefficients in the model can be modified by incorporating the information into the model, thereby making it more competent. The application of such methods to epidemiologic research on estimation of covariate effects and predictive mapping has been demonstrated in two studies.39,40 The logistic regression model created in the current study can be used widely in other epidemiologic surveys by simply changing the coefficients in the software. The current analysis provides a more rigorous analytical approach, potentially resulting in more accurate parameters and significant estimates, as well as increased predictive accuracy.41

In summary, gaining an overview of the seropositivity of E. histolytica infection in seven provinces of China, coupled with our logistic regression model estimation method, provide a more accurate measure of incidence and prior probability of the prevalence of infection, thereby facilitating better resource allocation to protect the population from public health concerns. The logistic regression model has general applicability to any sequential serologic data set obtained over a period of changing incidence.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Financial support: This study was supported by grants from the Major Project of the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (No. 2009ZX10004104), the National Science Foundation of China (No. 30771878 and No. 81771594), and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (No. 23117009 and No. 24406013).

Authors' addresses: Bin Yang and Xunjia Cheng, Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, E-mails: scobin3@gmail.com and xjcheng@shmu.edu.cn. Yingdan Chen and Longqi Xu, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute of Parasitic Disease, Shanghai, China, E-mails: cyingdan@yahoo.com.cn and xlongqi@yahoo.com.cn. Liang Wu, Department of Information and Computing Sciences, School of Mathematical Sciences, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, E-mail: wuliang514@gmail.com. Hiroshi Tachibana, Department of Infectious Diseases, Tokai University School of Medicine, Isehara, Kanagawa, Japan, E-mail: htachiba@is.icc.u-tokai.ac.jp.

References

- 1.WHO/PAHO/UNESCO report A consultation with experts on amoebiasis. Epidemiol Bull. 1997;18:13–14. Mexico City, Mexico, January 28–29, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guerrant RL. Amebiasis: introduction, current status, and research questions. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8:218–227. doi: 10.1093/clinids/8.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stauffer W, Ravdin JI. Entamoeba histolytica: an update. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003;16:479–485. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200310000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diamond LS, Clark CG. A redescription of Entamoeba histolytica Schaudinn, 1903 (Emended Walker, 1911) separating it from Entamoeba dispar Brumpt, 1925. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1993;40:340–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1993.tb04926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sen A, Chatterjee NS, Akbar MA, Nandi N, Das P. The 29-kilodalton thiol-dependent peroxidase of Entamoeba histolytica is a factor involved in pathogenesis and survival of the parasite during oxidative stress. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:664–673. doi: 10.1128/EC.00308-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samie A, Obi LC, Bessong PO, Stroup S, Houpt E, Guerrant RL. Prevalence and species distribution of E. histolytica and E. dispar in the Venda region, Limpopo, South Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:565–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanyuksel M, Petri WA. Laboratory diagnosis of amebiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:713–729. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.4.713-729.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salit IE, Khairnar K, Gough K, Pillai DR. A possible cluster of sexually transmitted Entamoeba histolytica: genetic analysis of a highly virulent strain. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:346–353. doi: 10.1086/600298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh JA. Problems in recognition and diagnosis of amebiasis: estimation of the global magnitude of morbidity and mortality. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8:228–238. doi: 10.1093/clinids/8.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramos F, Moran P, Gonzalez E, Garcia G, Ramiro M, Gomez A, de Leon Mdel C, Melendro EI, Valadez A, Ximenez C. High prevalence rate of Entamoeba histolytica asymptomatic infection in a rural Mexican community. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73:87–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stauffer W, Abd-Alla M, Ravdin JI. Prevalence and incidence of Entamoeba histolytica infection in South Africa and Egypt. Arch Med Res. 2006;37:266–269. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanley SL., Jr Amoebiasis. Lancet. 2003;361:1025–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12830-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Hal SJ, Stark DJ, Fotedar R, Marriott D, Ellis JT, Harkness JL. Amoebiasis: current status in Australia. Med J Aust. 2007;186:412–416. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu SH, Xu LQ, Jiang ZX, Xu SH, Han JJ, Zhu YG, Chang J, Lin JX, Xu FN. Report on the first nationwide survey of the distribution of human parasites in China. Chin J Parasitol Parasitic Dis. 1994;12:241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haque R, Huston CD, Hughes M, Houpt E, Petri WA., Jr Amebiasis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1565–1573. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tachibana H, Kobayashi S, Nagakura K, Kaneda Y, Takeuchi T. Asymptomatic cyst passers of Entamoeba histolytica but not Entamoeba dispar in institutions for the mentally retarded in Japan. Parasitol Int. 2000;49:31–35. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5769(99)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Li E, Jackson TF, Zhang T, Gathiram V, Stanley SL., Jr Use of a recombinant 170-kilodalton surface antigen of Entamoeba histolytica for serodiagnosis of amebiasis and identification of immunodominant domains of the native molecule. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2788–2792. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.11.2788-2792.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soong CJ, Torian BE, Abd-Alla MD, Jackson TF, Gatharim V, Ravdin JI. Protection of gerbils from amebic liver abscess by immunization with recombinant Entamoeba histolytica 29-kilodalton antigen. Infect Immun. 1995;63:472–477. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.472-477.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tachibana H, Cheng XJ, Masuda G, Horiki N, Takeuchi T. Evaluation of recombinant fragments of Entamoeba histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin intermediate subunit for serodiagnosis of amebiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1069–1074. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1069-1074.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diamond LS, Harlow DR, Cunnick CC. A new medium for the axenic cultivation of Entamoeba histolytica and other Entamoeba. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1978;72:431–432. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(78)90144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng XJ, Hughes MA, Huston CD, Loftus B, Gilchrist CA, Lockhart LA, Ghosh S, Miller-Sims V, Mann BJ, Petri WA, Jr, Tachibana H. Intermediate subunit of the Gal/GalNAc lectin of Entamoeba histolytica is a member of a gene family containing multiple CXXC sequence motifs. Infect Immun. 2001;69:5892–5898. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5892-5898.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petri WA, Jr, Chapman MD, Snodgrass T, Mann BJ, Broman J, Ravdin JI. Subunit structure of the galactose and n-acetyl-D-galactosamine-inhibitable adherence lectin of Entamoeba histolytica. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:3007–3012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petri WA, Jr, Schnaar RL. Purification and characterization of galactose- and n-acetylgalactosamine-specific adhesin lectin of Entamoeba histolytica. Methods Enzymol. 1995;253:98–104. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(95)53011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng XJ, Tsukamoto H, Kaneda Y, Tachibana H. Identification of the 150-kDa surface antigen of Entamoeba histolytica as a galactose- and n-acetyl-D-galactosamine-inhibitable lectin. Parasitol Res. 1998;84:632–639. doi: 10.1007/s004360050462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosmer D, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. Second edition. New York: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng YL. An epidemiologic survey on Endoameba histolytica infection. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 1986;7:274–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang TH. Seroepidemiological study on amoebiasis. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 1988;9:217–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haque R, Neville LM, Wood S, Petri WA., Jr Short report: detection of Entamoeba histolytica and E. dispar directly in stool. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:595–596. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.50.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rivera WL, Tachibana H, Silva-Tahat MR, Uemura H, Kanbara H. Differentiation of Entamoeba histolytica and E. dispar DNA from cysts present in stool specimens by polymerase chain reaction: its field application in the Philippines. Parasitol Res. 1996;82:585–589. doi: 10.1007/s004360050169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamzah Z, Petmitr S, Mungthin M, Leelayoova S, Chavalitshewinkoon-Petmitr P. Development of multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction for detection of Entamoeba histolytica, Entamoeba dispar, and Entamoeba moshkovskii in clinical specimens. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:909–913. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nunez YO, Fernandez MA, Torres-Nunez D, Silva JA, Montano I, Maestre JL, Fonte L. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction amplification and differentiation of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar DNA from stool samples. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64:293–297. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shenai BR, Komalam BL, Arvind AS, Krishnaswamy PR, Rao PV. Recombinant antigen-based avidin-biotin microtiter enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for serodiagnosis of invasive amebiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:828–833. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.828-833.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abd-Alla MD, Jackson TG, Ravdin JI. Serum IgM antibody response to the galactose-inhibitable adherence lectin of Entameoba histolytica. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:431–434. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stanley SL, Jr, Jackson TF, Foster L, Singh S. Longitudinal study of the antibody response to recombinant Entamoeba histolytica antigens in patients with amebic liver abscess. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:414–416. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Y, Zhang Y, Yang B, Qi T, Lu H, Cheng X, Tachibana H. Seroprevalence of Entamoeba histolytica infection in HIV-infected patients in China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li E, Stanley SL. Protozoa. Amebiasis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1996;25:471–492. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Batchelor NA, Atkinson PM, Gething PW, Picozzi K, Fevre EM, Kakembo ASL, Welburn SC. Spatial predictions of Rhodesian human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) prevalence in Kaberamaido and Dokolo, two newly affected districts of Uganda. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e563. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wardrop NA, Atkinson PM, Gething PW, Fevre EM, Picozzi K, Kakembo AS, Welburn SC. Bayesian geostatistical analysis and prediction of Rhodesian human African trypanosomiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hay SI, Guerra CA, Gething PW, Patil AP, Tatem AJ, Noor AM, Kabaria CW, Manh BH, Elyazar IR, Brooker S, Smith DL, Moyeed RA, Snow RW. A world malaria map: Plasmodium falciparum endemicity in 2007. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000048. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Craig MH, Sharp BL, Mabaso ML, Kleinschmidt I. Developing a spatial-statistical model and map of historical malaria prevalence in Botswana using a staged variable selection procedure. Int J Health Geogr. 2007;6:44. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-6-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clements AC, Lwambo NJ, Blair L, Nyandindi U, Kaatano G, Kinung'hi S, Webster JP, Fenwick A, Brooker S. Bayesian spatial analysis and disease mapping: tools to enhance planning and implementation of a schistosomiasis control programme in Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:490–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.