Abstract

Objectives.

This study examines coresident relationships in assisted living (AL) and identifies factors influencing relationships.

Methods.

We draw on qualitative data collected from 2008 to 2009 from three AL communities varying in size, location, and resident characteristics. Data collection methods included participant observation, and informal and formal, in-depth interviews with residents, administrators, and AL staff. Data analysis was guided by principles of grounded theory method, an iterative approach that seeks to discover core categories, processes, and patterns and link these together to construct theory.

Results.

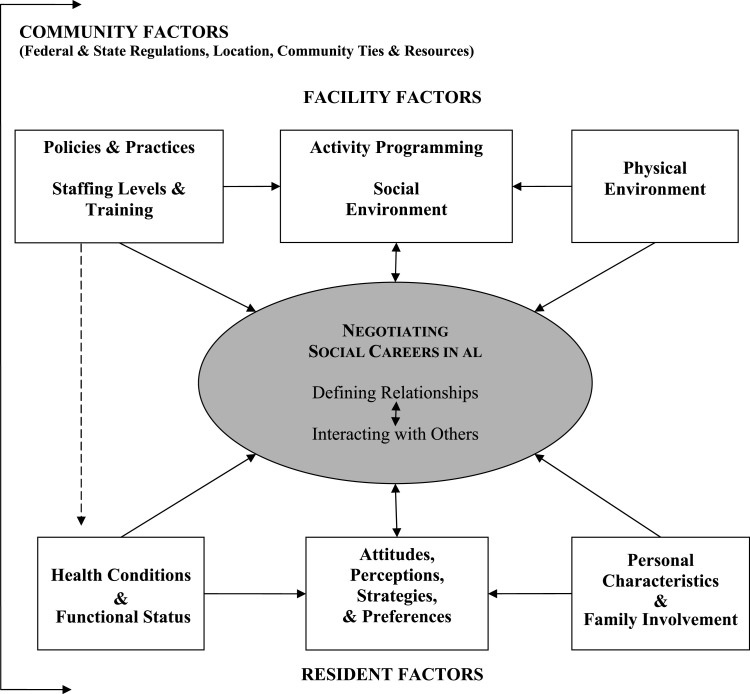

The dynamic, evolutionary nature of relationships and the individual patterns that comprise residents’ overall experiences with coresidents are captured by our core category, “negotiating social careers in AL.” Across facilities, relationships ranged from stranger to friend. Neighboring was a common way of relating and often involved social support, but was not universal. We offer a conceptual model explaining the multilevel factors influencing residents’ relationships and social careers.

Discussion.

Our explanatory framework reveals the dynamic and variable nature of coresident relationships and raises additional questions about social career variability, trajectories, and transitions. We discuss implications for practice including the need for useable spaces, thoughtful activity programming, and the promotion of neighboring through staff and family involvement.

Keywords: Assisted living, Qualitative methods, Social careers, Social relationships, Social support

Social relationships—the recurrent patterns of interaction with others—have profound effects on individuals’ physical and mental well being throughout the life course (Antonucci, Birditt, & Akiyama, 2009). The protective influences of supportive social relationships are especially important in later life when the risk of social isolation and loneliness increases alongside decreases in social network size and activity that commonly accompany life course transitions such as widowhood and health decline (Antonucci, Akiyama, & Takahashi, 2004). Family members can be key sources of support for older adults, but friends are more influential for well being, feelings of self-worth, and morale than are family (Keller-Cohen, Fiori, Toler, & Bybee, 2006). To the extent that relationships with age-peers are reciprocal and satisfying, they can make up for the absence or loss of a partner and help prevent loneliness (Adams & Blieszner, 1995).

Increasingly, later life for older adults will include the transition to assisted living (AL), which, similar to other senior housing and care settings, simultaneously offers and limits social opportunities (Eckert, Carder, Morgan, Frankowski, & Roth, 2009). These nonmedical, community-based living environments provide shelter, board, 24-hr protective oversight, and personal care services to nearly one million individuals nationwide (Golant, 2008). AL encompasses a range of settings that vary in size, service provision, regulatory standards, funding, fees, and resident characteristics (Polivka & Salmon, 2008). The typical resident is White, female, 87 years old, and requires assistance with approximately two activities of daily living (National Center on Assisted Living, 2009). Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias are prevalent with estimates ranging from nearly half (Ball, Perkins, Hollingsworth, & Kemp, 2010) to 67.7% (Leroi et al., 2006). Although functional decline, cognitive and or physical, is the basis of most decisions to move to AL, moves also often are precipitated by loss of a spouse and increased social isolation (Ball, Perkins, Hollingsworth, Whittington, & King, 2009), magnifying the importance of social relationships in AL.

AL residents have varying social opportunities. Some retain active community connections (Yamasaki & Sharf, 2011). Others depend exclusively on those who visit, work, and live in AL for interaction (Ball et al., 2005). Although family support is important, some residents have none and most family members are not available daily (Ball et al., 2000, 2005). Meanwhile, staff-resident relationships can be significant to residents (Ball et al., 2005; Eckert, Zimmerman, & Morgan, 2001) but staff often have little time to socialize (Ball, Lepore, Perkins, Hollingsworth, & Sweatman, 2009; Kemp, Ball, Hollingsworth, & Lepore, 2010).

AL research suggests resident–resident relationships influence life satisfaction (Park, 2009), subjective well-being (Street & Burge, 2012), and quality of life (Ball et al., 2005; Street, Burge, Quadagno, & Barrett, 2007). Few studies, however, have examined systematically coresident connections and research is somewhat inconclusive (Eckert et al., 2001). For instance, a qualitative study of two AL settings found that residents formed few social bonds (Frank, 2002). Yet, Ball and colleagues (2000, 2004, 2005) found evidence of continuing lifelong patterns of self-isolation alongside friend- and family-like ties, helping relationships, and cliques (Perkins, Ball, Whittington, & Hollingsworth, 2012).

Variation in coresident relationships in AL indicates the potential influence of facility factors. Some studies suggest smaller facilities and those with physical layouts that promote interaction have the highest level of coresident closeness (Ball et al., 2005; Eckert et al., 2001). Whether or not residents with dementia are integrated, with other residents in a facility also can affect the social environment (Eckert et al., 2009). Admission and discharge policies are likely to be influential. For instance, certain facilities do not admit or retain residents with severe dementia (Chapin & Dobbs-Kepper, 2001; Street, Burge, & Quadagno, 2009) or a history of mental illness (Ball et al., 2005). These practices shape resident populations and consequently affect residents’ social relationships and the overall social environment, in part because of the connection between functional status and stigmatization of residents in AL (Ball et al., 2005; Dobbs et al., 2008; Perkins et al., 2012). Moreover, facilities often cater to specific resident populations (Ball et al., 2009), including for example, a particular class (Perkins, Ball, Whittington, & Combs, 2004) or racial or ethnic group (Ball et al., 2005), making resident-facility fit potentially important. Residents arrive with differing histories and experiences (Yamasaki & Sharf, 2011), but homogeneity, including shared religious beliefs and ethnicity, can promote connections (Ball et al., 2005; Eckert et al., 2001).

Resident relationships likely vary by individual factors. Women tend to have larger and more varied networks than men (Antonnuci, 1990), who are greatly outnumbered by women in later life and have fewer opportunities for same-sex friendships, especially in AL. Research involving married couples in AL indicates they are a minority and that spouses often emphasize relationships with one another to the exclusion of others (Kemp, 2008, 2012). Hearing and speech impairments (Hubbard et al., 2003), incontinence (Eckert et al., 2009), as well as cognitive functioning and language skills (Keller-Cohen et al., 2006), also can influence interaction. So too can residents’ relationship strategies. Research shows higher functioning AL residents often avoid frailer residents, especially those with cognitive impairment (Dobbs et al., 2008; Eckert et al., 2009). Finally, Burge and Street (2010) found a positive relationship between contact with community-dwelling family and friends and quality of coresident relationships in AL.

Existing research on AL residents’ connections suggests they are important, yet variable, and apt to be influenced by a range of multilevel factors. Few studies, however, have examined in-depth the social processes underlying coresident relationships, and none has methodically examined influential factors. The significance of social relationships, paired with the demand for AL, lead us to address existing knowledge gaps with the following aims: (a) to understand how residents experience coresident relationships in AL, including the underlying social processes, the nature and meaning, and attitudes and expectations regarding relationships; and (b) to understand how individual-, facility-, and community-level factors shape coresident relationships in AL.

Design and Methods

Data for this analysis are drawn from a 3-year (2008–2011), externally funded, mixed-methods study, “Negotiating Social Relationships in Assisted Living: The Resident Experience.” The overall aim was to learn how to create environments that maximize residents’ ability to negotiate and manage their relationships with other residents. We collected data in eight AL sites, which varied in size, location, ownership, and resident profiles. A ninth site was added only to increase the number of quantitative surveys. Facilities were selected and studied in two phases. The present analysis uses qualitative data from the three facilities studied in Phase 1 and was completed while the second phase of data collection was ongoing. The three settings analyzed in this paper are unique in their own right by having resident populations not found in Phase 2 facilities. Cross-case analysis of Phase 1 facilities provides the unique opportunity to focus in-depth on individual-, facility-, and community-level factors that shape the social environment in AL facilities that vary along lines of resident race, ethnicity, and culture. A strong suit of our grounded theory approach will be our ability to synthesize these findings with ongoing analysis of data from Phase 2 facilities, which were selected for other distinct characteristics such as size, design, ownership, and location. Table 1 describes select setting characteristics. The project was approved by Georgia State University's Institutional Review Board. For purposes of anonymity, we use pseudonyms.

Table 1.

Select Characteristics by Setting (2008–2009)

| Characteristic | Feld Housea | Oakridgea | Pineview |

| Capacity/average census | 42/22 | 55/45 | 68/66b |

| Number of residents during study period | 41 | 65 | 83 |

| For profit | No | Yes | Yes |

| Ownership | Private | Corporate | Corporate |

| Monthly fee range | $2,300–$3,800 | $2,700–$5,295 | $2,985–$4,195 |

| Race or culture | White 99% Jewish | African American | Mostly White |

| Percent men | 15 | 34 | 22 (A), 17 (B) |

| Married couples | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| Sibling pairs | — | — | 2 |

| Number in wheelchairs | 16 | 14 | 16 (A), 14 (B) |

| Percent with dementia (AL) | 44 | 34 | 21 |

| Dementia care unit | No | Yes | No |

| Age range | 52–99 | 54–102 | 73–98 |

| Number of deaths | 11 | 5 | 13 |

Notes. aFigures exclude extra care and dementia care unit residents.

Totals reflect Buildings A and B combined.

Data Collection

Hollingsworth, Kemp, and Ball engaged in data collection and led teams of trained sociology and gerontology graduate researchers in Feld House, Oakridge, and Pineview, respectively. Table 2 provides data collection information by type and location. Each team conducted participant observation and informally interviewed administrative and care staff, residents, and visitors, including community-dwelling friends and family. The number of researchers assigned and the amount of time spent in each home depended on facility census. Over a 1-year period, visits occurred three to four times weekly, varied by days and times, and were documented in detailed field notes. Owing to our yearlong time frame, we spoke with, observed, and/or learned about all AL workers and residents and many visitors. Additionally, we conducted in-depth, qualitative interviews with all AL administrators and activity staff and certain care workers purposively selected for knowledge of residents and their relationships. Interviews inquired about residents’ social relationships and relevant facility policies and practices. We also invited all residents with three or more months facility tenure and the cognitively ability to give informed consent to participate in surveys. Of the 87 residents invited to participate, 21 declined, citing lack of interest, privacy, or health issues. Surveys gathered data on residents’ personal and health characteristics, functional status, and support needs, as well as their social networks. Residents also were asked to explain the nature of their coresident relationships. Additionally, we used theoretical sampling based on our research questions and emerging themes (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) to select 28 residents for in-depth interviews based on variation in: gender, functional status, marital and family status, facility tenure, race, ethnicity, and age. One resident declined to be interviewed. Interviews addressed residents’ AL life, particularly social relationships, including: the nature of coresident relationships; when, where, and how often they interacted with other residents; strategies for getting to know others; and perceptions of how various resident and facility factors affect coresident relationships. All formal interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed, and, as with surveys, were conducted in-person at a time and location selected by participants.

Table 2.

Data Collection by Type and Location (2008–2009)

| Feld House | Oakridge | Pineview | Total | |

| Number of researchers | 2 | 3 | 4 | 9 |

| Participant observation (hr/visits) | 403/134 | 578/178 | 691/209 | 1,672/521 |

| Interviews (n) | ||||

| Administrator | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Activity staff | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Care staff | 1 | 3 | 4 | 8 |

| Resident | 5 | 9 | 13 | 27 |

| Resident surveysa (n) | 19 | 19 | 28 | 66 |

Note. aAll but three residents (one in Feld and two in Pineview) who were interviewed also participated in the survey.

Data Analysis

Our qualitative analysis was informed by principles of grounded theory method (GTM)—an approach used to understand and develop theory about social processes (Charmaz, 2006; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Social relationships are formed, maintained, and terminated through social processes, making GTM highly appropriate for our purposes. GTM consists of a constant comparative method of inquiry in which data collection, hypothesis generation, and analysis occur simultaneously (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). GTM involves a three-stage coding process. All co-authors, with other research team members, developed, discussed, and refined coding categories throughout the data collection process. Three senior team members coded, verified one another’s coding, and worked together to achieve consensus. We used the qualitative software, NVivo 8.0 to facilitate data management and analysis. Notably, our team approach to data collection and analysis and inclusion of multiple participant types and modes of data collection afford triangulation and enhance credibility.

Coding procedures followed those outlined by Strauss and Corbin (1998). We used line-by-line or open coding to look for concepts based on the data and guided by our research questions. Initial codes included, for example, greeting, gossiping, and distancing. Next, axial coding involved linking categories and making connections between the data indicating relationships, conditions, context, and consequences. We noted, for example, that certain community-level factors join key facility- and resident-level factors, which intersect to shape relationships. Finally, we integrated and refined categories to form a larger conceptual scheme through selective coding, organizing our categories around our core category, “negotiating social careers in AL.” This category represents our data’s central “story line”; namely, residents’ experiences with coresident relationships are worked out over time and assume different configurations and trajectories. Consistent with GTM, we returned to the literature with our findings (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) and discovered that Humphrey (1993: 166) coined the term, “social career” to represent lifelong social participation patterns. His work builds on Johnson (1976: 157–158), who, following Goffman (1961), suggests careers “relate to a particular life activity” (e.g., work, family), but additionally notes the existence of different “career lines” (e.g., worker, spouse). We adapt the concept to refer to a specific “career line” in AL and to capture the totality of AL residents’ coresident relationships and the dynamism and variation generated by time and context.

Results

Negotiating Social Careers in AL

Our core category, “negotiating social careers in AL” offers an explanatory framework for understanding coresident relationships, including individual and shared experiences and continuity and change. Relationship experiences varied among residents as well as for residents across time and relationship partner. On an ongoing basis, residents negotiated (i.e., worked out) their relationships with their fellow residents and consequently their social careers in AL—a process that involved defining (and redefining) relationships and interacting with others and one shaped by a variety of multilevel factors.

Social careers in AL began upon relocation when coresidents typically were unknown and were forged throughout residents’ tenure. Careers were personalized, varying in duration, composition (e.g., “They’re [all] just acquaintances” or “They’re all friends”), and content (e.g., friendly/neighboring or unfriendly/antineighboring). Overall levels of social engagement and attachment also ranged considerably and were stable or changeable over time. One resident explained her career:

When I first came here, I enjoyed some of the activities. After awhile, I got where I was tired. I was hard of hearing. I couldn’t hear everything and now I just enjoy reading and sitting here really by myself and I have the friends at tables. We chat and enjoy each other at the tables and that’s really about my only communication with others here.

Fieldnotes describe Sally’s social career, as told by a staff member, Dora:

When Sally first came to Feld, she was very isolated and never came out of her room. Dora specifically asked two of the more outgoing female residents to make an effort to include her. Eventually Sally opened up and now is very social.

Some careers reflected lifelong social patterns and preferences: “I’m a bit peculiar. I love people, but I don’t socialize that much. My mother always said, ‘Don’t get too close to people.’” For others, relocation and accompanying transitions represented change to lifelong social patterns or “career breaks” (Humphrey, 1993: 172).

Defining and Redefining Residents’ Relationships

Defining coresident relationships was a key process in negotiating residents’ social careers in AL. Relationships varied widely by resident and relationship partner, yet we found similar types of connections across facilities. “Stranger” often defined others upon move in. A new Feld resident commented, “Everyone here are strangers.” Even those with greater tenure continued to define some or all others as strangers. A Pineview resident of 4 months remarked, “I don’t have any relationships with the people who live here.” Implying more familiarity, residents frequently characterized others as “acquaintances.” One explained, “I have acquaintances here, but don’t get too involved.” Another said, “I know faces.” Occasionally residents were enemies, including a Feld resident who described her rival, saying, “I hate her. She is no damn good.” Cliques also developed across sites, more so among women than men.

Sometimes residents developed friendships. Some residents perceived friendships as “artificial” or “by circumstance,” occurring, as one Pineview man explained, “simply because they live in the same place.” Residents also distinguished AL friendships from ones they considered “real.” A female resident from Pineview noted, “[I] consider a lot of them friends, but don’t have the ‘I have something I want to tell you relationship.’” A male resident from Feld House echoed: “I mean they’re all friends [but] I don’t confide in them, you know what I mean. We’re all separate. It’s not like when you’re younger.” Other residents acknowledged a difference but viewed AL friendships as meaningful and beyond situational. A Feld resident spoke of her friendship with a coresident who passed away, noting, “I’m glad that we had the good times … . I don’t think it was the intensity that one would have with a 40-year old friend … there wasn’t any reason for it to be.”

Several romantic partnerships developed, including an Oakridge resident who reported meeting his “Sweetie Peatie.” For a few, other residents became “just like family.” Fewer still were connected by blood or marriage (see Table 1).

Interacting With Others

Coresident interaction influenced and was influenced by how residents defined relationships and consequently was an important process associated with negotiating social careers. We observed two general ways of interacting: neighboring and antineighboring.

Neighboring.—

On balance, resident interactions generally were supportive and pleasant. We refer to these friendly behaviors as “neighboring social support”—a term used by Wethington and Kavey (2000, p. 190) in their study of community-dwelling older adults to “characterize friendly but not necessarily close or intimate relationships between” neighbors. In AL, neighboring can be fostered by a shared sense of place and of, as one resident explained, “all [being] somewhat incapacitated in some kind of way.”

Neighboring sometimes began and ended with pleasantries and characterized social careers. One Pineview resident explained, “Right now I really have no relationships other than greeting them.” An Oakridge resident noted, “When I see them, we speak. That’s all. I don’t have no special friends.” Other residents found companionship through neighboring, frequently by “do[ing] things together” or visiting. Conversations transpired during structured and informal activities. Residents discussed a variety of topics, including their families, the past, television, sports, religion, and politics. Joking, gossiping, flirting, and teasing occurred frequently. Occasionally, visiting took place in residents’ rooms and was indicative of more intimate relationships such as good friends, romantic partners, and family.

Regardless of relationship type, neighboring also could involve sharing, concern, and helping. Residents shared food, books, newspapers, CDs, glasses, walkers, and musical talent. They routinely expressed concern for one another, particularly related to illness or frailty. One resident commented, “I worry about [my neighbor] and I’ll mention something to [the staff] if I think it needs [their] attention. I have nothing in common with her other than I worry about her.” Residents in all facilities helped one another by pushing wheelchairs, giving directions, monitoring dietary needs and preferences, providing reminders about and meals and activities, and assisting with eating. More personal or intimate support, such as assistance with dressing, was exchanged mainly between spouses and siblings.

Antineighboring.—

Some interactions represented the antithesis of neighboring and ran the gamut from established enmity to transitory hostility. We observed bullying, name-calling, intolerance, gossiping, shunning, harassing, disagreements, and physical confrontation. Negative behaviors typically were displayed during organized activities, meals, and informal gatherings and usually involved but were not exclusive to enemies, clique members, and troublemakers. For example, during an activity at Feld, a researcher noted: “Irving said something to Hillary and she told him, ‘Get away you slob!’ A staff person [told him] to go on the other side of the room … Irving started aggravating Hillary from across the room. He yelled out to Hillary, ‘Hey Chubby.’” A Highland resident, whose romance with a male resident was fodder for gossip among a clique of women said, “I think they talk about me real bad.” Along with cliques, gossip created and maintained boundaries, simultaneously excluding certain residents while creating bonds among others (see also Perkins et al., 2012).

Factors Influencing Coresident Relationships

Coresident relationships were influenced by intersecting multilevel factors. Figure 1 illustrates these factors and their influence on relationships, interactions, and, consequently, residents’ social careers. Community-level factors set the context and join facility- and resident-level factors, which intersect. In turn, these experiences influence activity programming and a facility’s social environment, as well as residents’ attitudes, preferences, and strategies. Each level is elucidated below.

Figure 1.

Factors influencing residents’ social relationships and careers in assisted living.

Community

Defined as those external to facilities, community factors operated on three levels. At the federal level, facilities are bound by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Designed to protect individual’s privacy in a communal setting, HIPAA interfered with residents’ knowledge of one another during times of illness-related relocation (e.g., hospitalization) and was a barrier to neighboring. Oakridge’s administrator explained, “It would be like you sitting with somebody all your life or for the last five years of your life and then they’re gone [and] you can’t explain what happened … they think it’s ridiculous and they get very upset.” At the state level, although interpretations varied across facilities, AL regulations often impeded aging in place, and, once relocated to another setting, usually a nursing home, most relationships “don’t continue.” Finally, local community characteristics influenced relationships. Atlanta’s robust Jewish community influenced the resident profile and activity programming at Feld House. Nearby churches made similar supportive contributions to Oakridge and Pineview. Numerous residents at both facilities had previous or common community connections, often through churches and schools. Pineview’s small-town location further promoted community ties.

Facility

The main facility-level factors influencing residents’ social relationships in AL included: size; physical and social environment; policies and practices; staffing characteristics; and activity programming. Within these broad categories, two factors (mealtimes and lack of policies governing coresident interaction) operated in common ways across facilities. Yet on balance across-facility differences meant little uniformity. Below we discuss commonality before illustrating the specifics of each setting.

Commonalities.—

Mealtimes were key and affected coresident relationships similarly across facilities. Mealtimes structured daily routines, offered social venues, and were essential to relationship building. We observed greeting, conversations, tiffs, expressions of concern, helping, and sharing. Seating typically depended on “availability” and “assessment,” which often was a trial and error process. In each site, although few formal policies governed relationships, helping (e.g., pushing wheelchairs) was permitted albeit with informal guidelines. Feld House’s activity director explained, “If someone doesn’t like it” residents “need to stop.” Oakridge’s activity director noted, “Safety is our number one thing; so as long as there’s not a risk of their safety, we don’t mind helping one another.” Beyond these influences, however, each facility differed in combinations of factors influencing relationships.

Feld House.—

The average census was 22 residents, which enhanced familiarity but limited potential interaction partners. The mostly Jewish population promoted a basic level of commonality. One staff member observed, “Being Jewish is the one unifying thing. If nothing else, you’re Jewish.” High levels of family and community involvement fostered a sense of community.

Feld’s physical design impeded relationships. One staff member commented, “Whoever designed it didn’t do a good job of thinking about older people in wheelchairs and walkers. The space, we don’t have enough as far as activities.” Only the dining room accommodated all residents but remained closed outside of mealtimes. Small conversation areas and a TV room went largely unused. Although the sunroom was where most activities took place, it was where staff placed the more severely impaired residents, who slept regularly, rarely talking. Less impaired residents avoided this space. Severely impaired residents were further segregated during meal times in a separate dining room. Nevertheless, several staff practices promoted familiarity and included: encouraging residents to communicate and share information about personal histories and families and introducing new residents in small groups.

Transitions in Feld’s activity program demonstrated the importance of hiring decisions. A supervisor described an activity director who was dismissed, saying: “Gloria is not trained to do her job and she has no clue as to how to motivate residents to interact.” We observed Gloria discouraging residents from talking and ignoring or putting them down. Her replacement created a robust activity program, with certain activities organized around Jewish culture and individualized. Still, the relatively high level of impairment at Feld was a relationship barrier. Higher functioning residents habitually complained about being unable to relate to others, saying, for example, most “are gone [and] can’t remember.” A lenient policy regarding dying in place led to frequent deaths, resulting in a reluctance of some residents to pursue coresident connections.

Oakridge.—

With twice the average census, Oakridge offered more opportunity for coresident ties. All residents were African American, and many were college-educated professionals, providing commonality. The administrator explained: “They understand certain cultural heritage and the familiarity, all about relationships and education.”

The physical environment offered common spaces with comfortable seating conducive to resident interaction, including a spacious lobby, sunroom, front porch, and seating areas by the elevator and in hallways on both floors. Residents used these spaces to observe, sleep, visit, and await meals. Staff encouraged residents, even the most impaired, to gather in common spaces before and after meals, which facilitated relationships and allowed residents with dementia to have regular interaction and meaningful relationships.

Staff encouraged participation in activities, including: daily exercise, games, religious services, outings, and activities centered on African American culture (e.g., Gospel Hour, jazz performances, community speakers, and trips to African American theater, dance, and music events). The activity director explained, “My goal is to make sure that our residents are engaged with one another, the staff, engaged with their family members and visitors. [We] encourage them to participate.” Sometimes activities were tailored to resident interest, such as gardening or walking. Men had special activities, including well-attended Happy Hours and dinners out. Women occasionally had separate activities, including bingo and dinners out.

Staff were familiar with residents’ biographies and tried to connect residents. One explained, “I try to group them where they’ll be with their own kind, a little group of people that they can have something in common together.” Residents often aligned according to function, occupation, and educational backgrounds. Consequently, cliques developed among residents who shared meals and formal and informal activities.

Numerous mechanisms helped residents get acquainted. New residents were introduced in resident council meetings and the newsletter, paired with “buddies,” and identified by signs outside their rooms. Still, residents felt, “They don’t openly tell us that we have a new resident.” The newsletter featured a resident of the month and announced birthdays, and a computer in the reception area occasionally featured resident photos. Families visited regularly and were informed about activities and events. Together with other environmental influences, these practices promoted a sense of community.

Pineview.—

Pineview consisted of two, one-story AL buildings with a total capacity of 68 and two, three-story buildings for independent residents. Another building, the Clubhouse, housed the administrative offices, dining room for independent residents, beauty shop, library, game room, and TV lounge. All buildings were connected by covered walkways and surrounded by grassy areas. AL buildings had identical layouts with resident rooms opening directly off common areas, including the dining room, which doubled as an activity space. Although offering the greatest opportunity for interaction partners among the three sites, several factors impeded the development of a sense of community.

The physical layout created some opportunities for interaction. Each AL apartment had a back patio, which when used by residents in neighboring apartments became spaces that promoted interaction. Fieldnote data note residents “who share a porch” “sitting and talking” or “smoking” together. The beauty shop promoted interaction and information exchange, particularly among women. The distances between buildings, however, and the heavy exit doors and exposure to the elements were barriers to cross-campus interaction, except for the most determined and functional residents. The lack of common spaces conducive to informal interaction was noted by the administrator:

If we had a nice big room that they could play bingo in and maybe had a place to get up in the morning and go talk over the morning newspaper and what’s going on today in the activities. I don’t find they do that as much in the dining because it’s an open space and that’s their dining area that has a whole different function.

Activity staff planned activities, held at different times and locations, for all residents. Daily exercise and weekly activities (e.g., current events, word games) took place in each AL building with staggered schedules. A book group, card games, Happy Hour, and special events took place in the Clubhouse. Church services and movies happened in the independent buildings. Although all activities were open to all residents, intermingling was limited largely because staff members did not promote or facilitate attendance across buildings or consistently remind residents about activities. Their limited knowledge of residents (partly because of the large census and their office locations) constrained their ability to connect residents with commonalities and individualize activities. Moreover, activity staff typically included short-term high school volunteers or part-time staff with limited experience.

One AL building housed residents with greater frailty levels, resulting in less familiarity. Staff habitually transported more impaired residents to their rooms after meals, contributing to their isolation. Even higher functioning residents rarely lingered in the dining room, and for many, their pathways to meals largely determined acquaintances with others. In the other AL building, a group of residents regularly visited in the dining room before and after meals, in part because certain care staff joined them.

New residents were announced in the monthly newsletter (often not distributed to AL residents), yet little else routinely was done to integrate them into the community. According to the activity director, new residents were “given an activity calendar and a newsletter.” Residents who relocated from the independent buildings sometimes had prior coresident connections.

Resident Factors

Residents’ personal characteristics, family involvement, health conditions, and functional status directly influenced relationships. As shown in Figure 1, these factors also influenced and interacted with attitudes, preferences, and behaviors to shape relationships.

Characteristics.—

Age, race, and culture were influential. Some younger residents (e.g., >70 years) felt they did not “fit in,” and disliked living with “all of the old people.” Yet others helped older residents. Being at opposite ends of the spectrum earned residents such labels as “the young one” or “the oldest.” Similarity in age offered a degree of commonality.

Race was unifying at Oakridge. Although Pineview staff and residents said race had no effect, certain White residents made racist comments and directed racial epithets at Black staff, making racism part of the environment. At Feld House, certain residents distinguished between “European” and “American Jews,” with the former feeling alienated. In all homes, regional identities were influential. “Northerners” described feeling “different” and having little “in common.” Similarity created connections (e.g., “A fellow New Yorker, that’d be great.”).

Most residents felt gender had little influence, but relationship opportunities were gendered. Men had fewer same-sex and more opposite-sex relationship opportunities compared to women and were more likely partnered. Married couples, romantic partners, and siblings had built-in companionship. This interdependence, particularly if caregiving was involved, limited coresident relationships, but sometimes was preferred. One husband said, “My day revolves around what she’s going to do, where she’s going to be.” Interdependence also could exacerbate the death or discharge of a partner because lack of other AL relationships.

Friendships were more apt to develop between those with similar backgrounds. Oakridge’s administrator noted, “Friendships have also developed by professions. You got a group of tables that are just teachers and you got a couple men that have been in the military.” Meanwhile, perceived differences could be influential. Illustrating the influences of social class and appearance, a retired teacher at Oakridge avoided certain residents noting, “I don’t know how some of these residents pay to live here because they look like they don’t belong.” Clique membership often was based on physical appearance.

Mutual interests around music, sports, gardening, books, art, travel, and even pornography provided a foundation for relationships. Smoking and drinking created bonds, even among residents with little in common. Residents united over religion (“brings us closer together”), church membership, and politics, despite dissimilar views (e.g., “We have three Democrats and one Republican, and we do disagree there, but we disagree gracefully.”). Findings show personality also influenced relationships. Some residents who described themselves as “very private” or lifelong “loners” preferred to spend time alone rather than interacting in group settings.

Facility-assigned characteristics such as mealtime seating and apartment locations were influential. One resident noted, “I feel closer to those people that I see, those people who are closer to me in the dining area, those people that are closer to me in the hallway, that I pass more often going to and fro.” Although no universal turning point existed, tenure could be important. For example, a new resident explained her reluctance to engage in activities, “I am not ready to go out among these strangers.” Time could increase familiarity and affect social careers. A Pineview resident explained, “When you first meet people, you can kind of tell if that’s the kind of person you want to build a friendship with. And then as it progresses and you find you have more and more things in common, it grows and grows.”

Families.—

Residents who relied mainly on family relationships were limited socially, but it was rare for family members to interfere directly in coresident relationships. However, one Oakridge resident with moderate dementia routinely visited another resident in her room until as a staff member explained, “the family got word [and] didn’t want [her] in there.” Family members successfully promoted relationships by participating in activities, encouraging residents to get out “to meet and greet,” and visiting. Some included other residents—especially friends and romantic partners—on outings for dinner, church, or other events. Lack of family could make coresident relationships more important. One resident described her tablemates saying, “They’re all I’ve got now.”

Health, Functional Status, and Helping.—

Health conditions and functional status were among the most influential factors. More impaired residents often received help from coresidents, especially those in close proximity, which increased familiarity. Certain residents considered helping an important role and facet of their identity. One helper said, “If you see somebody hung up or can’t get around and you have strength to do that, that’s a waste of love [not to help]. If I can do anything to help somebody, it’s pleasing to me.” Helping patterns often were supported by religious beliefs or professional identities, especially among retired helping professionals. A former teacher explained, “Well, there is one lady in particular who needs help in coming back and forth to her room—she’s in a wheelchair.”

Disability could be a basis for exclusion, avoidance, and intolerance. Frequent medical appointments, pain, incontinence, mobility, speech, and hearing difficulties, depression, and dementia all reduced social opportunities, interests, and abilities. Functional decline happened over time, precipitating social career transitions. One resident noted a common challenge, “We can’t be friends like we used to be because she’s just gone downhill tremendously. She says the same thing over and over.”

End-of-life transitions were influential. In addition to the loss of relationship partners, decline and death among coresidents typically were observed by, speculated about, and discussed among residents. Responses to death ranged from indifference, to grief, and/or to a sense of peace, and depended on coresident relationship.

Attitudes, Preferences, and Strategies.—

Attitudes about being in AL or a given facility and toward relationships were pivotal. Attitudes related to residents’ overall social preferences and behaviors, including their generalized and individualized relationship strategies and, consequently, their social careers. Residents’ generalized approaches varied according to their global relationship desires. One explained, “It’s too much trouble to make friends. I don’t care about having them. I am happy in my room.” Others were more open to social engagement. For a few residents, antagonism was the primary strategy, earning them negative reputations, including an Oakridge resident who routinely “lifts his cane off the floor and pokes people with it.” More commonly, residents employed neighboring. The most proactive residents invited interaction and relationships by welcoming new residents, keeping apartment doors open, attending activities, and sitting in public spaces.

Individualized strategies varied widely. Although certain residents took extra steps to connect with others, even those with “annoying” behaviors, some socially distanced themselves from particular residents. One resident distinguished between his generalized and individualized approaches: “I try to be friendly to all of those that I come in contact with. There are some that I don’t go out of my way to be in contact with.” Undesirable behaviors were tolerated more from residents regarded as “sweet” compared to those viewed as “trying to ruin everything” regardless of cognitive status.

Discussion

This article examines coresident relationships in AL across three distinct settings. Informed by principles of GTM, our work presents “negotiating social careers in AL” as an explanatory framework for theorizing the dynamic and variable nature of coresident relationships, the totality of coresident relationships, and variations in social patterns by individuals and over time. Key processes involved in negotiating social careers include defining and redefining relationships and, related, interacting with coresidents. The ways residents defined their relationships echo and build on existing findings about the range of relationships (strangers to friends) previously noted in AL. We offer a conceptual model illustrating the multilevel factors influencing coresident relationships and interactions (including neighboring and antineighboring), and social careers in AL. Our findings advance knowledge of older adults’ social relationships, especially in AL by providing an in-depth account of relationships and influential factors.

Invoking the concept “social career” reveals the dynamic and evolutionary nature of residents’ individualized relationship patterns and experiences and has theoretical implications for understanding social experiences (see Humphrey, 1993). Residents’ social careers in AL were influenced by other “career lines” (Johnson, 1976: 157–158), especially those pertaining to health status and family relationships, and involved lifelong continuity for some and social “career breaks” (see Humphrey, 1993) for others. Our work demonstrates the theoretical value of taking a longer contextual view of relationships and raises questions about different social careers, including career trajectories and transitions in AL, and their influences on resident well being. Future research might wish to build on these ideas.

Our work advances the limited scholarly knowledge of friendship (Pahl, 2000) and suggests individuals can revise the meaning and content of friendship in later life. Some residents did not define AL friendships as “real” because they lacked history or confiding. For others, AL friendships were indistinguishable from the past or different, but equally meaningful. Understanding friendship requires contextualization (see Adams & Allan, 1998) and is another avenue for future study.

Neighboring is an important source of social support in the community (Wethington & Kavey, 2000), including age-homogenous settings (Hochschild, 1973). In our study, neighboring was the most common way of relating in AL and a key source of social support for residents. The occurrence of helping and other supportive acts across relationship type, particularly stranger or acquaintance, confirms the potential importance of peripheral (Fingerman, 2009) or weak ties (Granovetter, 1973) in AL. However, we also identified “anti-neighboring” behaviors, which indicate that relationships are not universally supportive and implies potentially negative influences on relationships, including peripheral ties. Living in facilities where the resident population is affinity based (i.e., race, ethnicity, and culture) can promote a sense of community, but does not guarantee against antineighboring, which can result in and stem from stigmatization based on a number of characteristics including age, disability, and class, a finding similar to those of other AL studies (Dobbs et al., 2008; Perkins et al., 2012). Facilities can take steps to promote neighboring and diffuse antineighboring, making these potential intervention areas.

Our conceptual model provides a comprehensive understanding of the multilevel factors influencing relationships. Certain factors such as residents’ age and gender are immutable, but others can be modified to promote relationships. For example, although a community-level factor, HIPAA's influence interfered with residents’ neighboring and could be addressed by facilities. Rather than withholding all information during resident hospitalization, administrators could work with residents and families to determine what, if any, information can disseminated.

As other AL studies have found, facility admission and retention policies are relevant to coresident relationships and affect social opportunities (Ball et al., 2005; Dobbs et al., 2008; Perkins et al., 2012). Aging (i.e., dying) in place is the preference of most residents and their families (Ball et al., 2005; Golant, 2008) and can positively influence relationships by providing continuity in resident connections. Yet, functional decline and death also can negatively affect coresident ties, as was the case in Feld House. Grief counseling for residents may help in this regard.

Our findings indicate the importance of spaces appropriately designed and utilized for social interaction. Oakridge had the most usable spaces whereas Feld’s design was not suitable for frail elders. In both, the combination of physical design and staff practices to encourage (or not) the space use affected residents’ interaction opportunities. Pineview had common spaces that went largely unused, mainly because of staff practices. Yet, it was the only site that permitted dining room use outside of mealtime. Future research might wish to explore the implication of dedicated spaces on relationships. Ultimately, designs that create useable common spaces, especially with a view of facility and community life, outdoor access, comfortable seating, and wheelchair accessibility, better promote interaction.

The importance of mealtimes for relationships makes seating assignment policies and practices consequential. Location can affect social relationships and, hence, careers, meaning the difference between social integration and isolation. Table assignments are driven mainly by pragmatic considerations such as availability, but staff should work with residents to find a good fit and continue to review seating-assignment suitability on a regular basis.

Similar to Keller-Cohen and colleagues (2006), we found promoting involvement in activities offers residents opportunities for more numerous and diverse relationships. Our data suggest activities promote interaction and should be designed to reflect the range of residents’ interests and abilities. A “one size fits all” approach inhibits participation. Best practices at Feld and Oakridge include activities tailored to their specific AL communities and individual residents. Activity programming requires ongoing evaluation. Resident preferences and abilities are apt to change over time alongside their social careers. Our data further indicate that activity programs are as strong as those hired to run them. Like those who provide hands-on care, individuals in staff activity positions typically are low-wage workers with limited education and skills. This bar should be raised, and, at a minimum, facilities should invest resources in programs and hire individuals with the talents required to work effectively with older adults.

As suggested, staff behavior is influential and can directly and indirectly influence coresident interaction (see also Doyle, de Medeiros, & Saunders, 2011). All AL staff should be educated about residents’ social needs and learn how to promote relationships. Oakridge, and to a certain extent Feld, demonstrated best practices. Staff members were familiar with residents and sought to promote interaction. With residents’ permission, we suggest that AL staff should know residents’ histories, interests, values, abilities, and social preferences. Small group activities can be useful in this regard. Practices also should address cognitively and physically impaired residents’ social needs, as was the case at Oakridge, where staff included residents with dementia in activities and encouraged them to spend time in common areas.

Community-building strategies could be used to promote familiarity and, presumably, neighboring. Newsletters, activity calendars, names on doors and dining tables, photos in common areas, resident interviews, and books with resident information are potential strategies. Families can be instrumental to community building in promoting staff–resident familiarity and in helping residents negotiate AL social careers. Greater family integration in facility activities at Feld House and Oakridge was attributable to strong community ties and facility communication. In addition to such practices, facilities also can educate family members about their potential influence (good and bad) on coresident relationships.

Our research has several limitations. First, data come from three facilities, all in Georgia, and do not represent the range of AL environments, including small homes, which house many low income and minority residents. Future research should include these oft-neglected homes (but see Ball et al., 2005; Perkins et al., 2004). Next, our analysis focused exclusively on coresident relationships. These relationships represent one dimension of residents’ social experiences. Understanding the relative importance of coresidents compared with family, staff, and community-dwelling friends, for example, is a matter for further analysis. Third, our effort to identify the multilevel factors affecting relationships meant none was presented in detail. Finally, our analysis draws exclusively on qualitative data and excludes our quantitative data.

Despite limitations, our research offers an explanatory framework, including a conceptual model that advances theorizing of AL residents’ relationships. Industry-wide trends toward admitting and retaining AL residents with greater cognitive and physical impairment could tempt providers to cater to physical over social needs. The changing AL landscape and heightened demand for care make investigating residents’ social needs and developing strategies to optimize relationships timely and imperative.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG030486-01A1 to M.M.B.).

Acknowledgments

A version of this paper was presented at 63rd Annual Meeting of the Gerontological Society of America in New Orleans, Louisiana. The authors wish to thank all those who participated in our study. We thank Mark Sweatman, Emmie Cochrane Jackson, Ailie Glover, Shanzhen Luo, Amanda White, and Terri Wylder for their assistance throughout the data collection process, and we appreciate the feedback and support of Elisabeth O. Burgess, Frank J. Whittington, Yarkasah Peter Paye, Amber Meadows, Vicky Stanley, Karuna Sharma, Navtej Sandhu, and Sophie Carssow.

References

- Adams RG, Allan G. Contextualising friendship. In: Adams RG, Allan G, editors. Placing friendship in context. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Adams RG, Blieszner R. Aging well with family and friends. American Behavioral Scientist. 1995;39:209–224. doi:10.1177/0002764295039002008. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC. Social supports and social relationships. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. The handbook of aging and the social sciences. 3rd ed. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Akiyama H, Takahashi K. Attachment and close relationships across the life span. Attachment & Human Development. 2004;64:353–370. doi: 10.1080/1461673042000303136. doi:10.1080/1461673042000303136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Birditt KS, Akiyama H. Convoys of social relations: An interdisciplinary approach. In: Bengston VL, Gans D, Putney NM, Silverstein M, editors. Handbook of theories and aging. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Lepore ML, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Sweatman M. “They are the reasons I come to work”: The meaning of resident-staff relationships in assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies. 2009;23:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2007.09.006. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Kemp CL. Overview of research. In: Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Kemp CL, editors. Frontline workers in assisted living. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2010. pp. 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Whittington FJ, King SV. Pathways to assisted living: The influence of race and class. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2009;28:81–108. doi: 10.1177/0733464808323451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Combs BL. Independence in assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies. 2004;18:467–483. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2004.06.002. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Combs BL. Communities of care: Assisted Living for African American Elders. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Whittington FJ, Perkins MM, Patterson V, Hollingsworth C, King SV. Quality of life in assisted living. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2000;19:304–325. doi:10.1177/0733464808323451. [Google Scholar]

- Burge S, Street D. Advantage and choice: Social relationships and staff assistance in assisted living. Journal of Gerontology: Sciences and Social Sciences. 2010;65:358–369. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp118. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbp118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin R, Dobbs-Kepper D. Aging in place in assisted living: Philosophy versus policy. The Gerontologist. 2001;41:43–50. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.1.43. doi:10.1093/geront/41.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide to qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs D, Eckert JK, Rubinstein B, Keimig L, Clark L, Frankowski AC, Zimmerman S. An ethnographic study of stigma and ageism in residential care or assisted living. The Gerontologist. 2008;48:517–526. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.517. doi:10.1093/geront/48.Special_Issue_III.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle PJ, de Medeiros K, Saunders PA. Nested social groups within the social environment of a dementia care assisted living setting. Dementia. 2011 Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/1471301211421188. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert JK, Carder PC, Morgan LA, Frankowski AC, Roth E. Inside assisted living: The search for home. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert JK, Zimmerman S, Morgan LA. Connectedness in residential care: A qualitative perspective. In: Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Eckert JK, editors. Assisted Living: Needs, practices, and policies in residential care for the elderly. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2001. pp. 292–313. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL. Consequential strangers and peripheral ties: The importance of unimportant relationships. Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2009;1:69–86. doi:10.1111/j.1756-2589.2009.00010.x. [Google Scholar]

- Frank JB. The paradox of aging in place in assisted living. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. New: York: Anchor Books; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Golant SM. The future of assisted living residences. A response to uncertainty. In: Golant SM, Hyde J, editors. The assisted living residence: A vision for the future. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2008. pp. 3–45. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter MS. The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology. 1973;78:1360–1380. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2776392. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild AR. The unexpected community: Portrait of an old age subculture. Los Angeles, CA: Prentice Hall; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard G, Tester G, Downs MG. Meaningful social interactions between older people in institutional settings. Ageing & Society. 2003;23:99–114. doi:10.1017/S0144686X02008991. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey R. Life stories and social careers: Ageing and life stories in an ex-mining town. Sociology. 1993;27:166–178. doi:10.1177/003803859302700116. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ML. That was your life: A biographical approach to later life. In: Munnichs JMA, van den Heuvel WJA, editors. Dependency or interdependency in old age. The Hague, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff; 1976. pp. 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- Keller-Cohen D, Fiori K, Toler A, Bybee D. Social relationships, language and cognition in the ‘oldest old’. Ageing & Society. 2006;26:585–605. doi:10.1017/S0144686X06004910. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL. Negotiating transitions in later life: Married couples in assisted living. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2008;27:231–251. doi:10.1177/0733464807311656. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL. Married couples in assisted living: Adult children’s experiences providing support. Journal of Family Issues. 2012;33:639–661. doi:10.1177/0192513X11416447. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL, Ball MM, Hollingsworth C, Lepore MJ. Connections with residents: “It’s all about the residents for me.”. In: Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Kemp CL, editors. Frontline workers in assisted living. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2010. pp. 147–170. [Google Scholar]

- Leroi I, Samus Q, Rosenblatt A, Onyike C, Brandt J, Baker A, Lyketsoset C. A comparison of small and large assisted living facilities for the diagnosis and care of dementia: The Maryland Assisted Living Study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;22:224–232. doi: 10.1002/gps.1665. doi:10.1002/gps.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Assisted Living. Assisted living resident profile. 2009. Retrieved from http://www.ahcancal.org/ncal/resources/Pages/ResidentProfile.aspx. Last accessed on February 5, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl R. On friendship. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Park NS. The relationships of social engagement to psychological well-being of older adults in assisted living facilities. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2009;28:461–481. doi:10.1177/0733464808328606. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins MM, Ball MM, Whittington FJ, Combs BL. Managing the care needs of low-income board-and-care home residents: A Process of negotiating risks. Qualitative Health Research. 2004;14:478–495. doi: 10.1177/1049732303262619. doi:10.1177/1049732303262619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins MM, Ball MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C. Relational autonomy in assisted living: A focus on diverse care settings for older adults. Journal of Aging Studies. 2012;26:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.01.001. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polivka L, Salmon JA. Assisted living: What it should be and why. In: Golant SM, Hyde J, editors. The assisted living residence: A vision for the future. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2008. pp. 397–418. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. The basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Street D, Burge SW. Residential context, social relationships, and subjective well-being in assisted living. Research on Aging. 2012;34:365–394. doi:10.1177/0164027511423928. [Google Scholar]

- Street D, Burge S, Quadagno J. The effect of licensure type on the policies, practices, and resident composition of Florida assisted living facilities. The Gerontologist. 2009;49:211–223. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp022. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street D, Burge S, Quadagno J, Barrett A. The salience of social relationships for resident well-being in assisted living. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Social Sciences. 2007;62:S129–S134. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.s129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wethington E, Kavey A. Neighboring as a form of social integration and support. In: Pillemer K, Moen P, Wethington E, Glasgow N, editors. Social integration in the second half of life. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2000. pp. 190–210. [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki J, Sharf BF. Opting out while fitting in: How residents make sense of assisted living and cope with community life. Journal of Aging Studies. 2011;25:13–21. doi:1016/j.jaging.2010.08.005. [Google Scholar]