Background: The intracellular signaling pathway leading to lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)-induced Egr-1 expression has been largely unknown.

Results: PKCδ-mediated activation of ERK and JNK is required for LPA-induced Egr-1 expression.

Conclusion: This study provides the first evidence of PKCδ regulation of ERK and JNK activation in LPA signaling and the role of PKCδ/ERK/JNK in LPA-induced gene expression.

Significance: Identified intracellular molecules may serve as therapeutic targets.

Keywords: Cell Signaling, Lipids, Protein Kinases, Signal Transduction, Vascular Biology, Vascular Disease

Abstract

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) modulates vascular cell function in vitro and in vivo via regulating the expression of specific genes. Previously, we reported that a transcriptional mechanism controls LPA-induced expression of Egr-1 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Egr-1 is a master transcription factor mediating the expression of various genes that have been implied to modulate a broad spectrum of vascular pathologies. In this study, we determined the essential intracellular signaling pathway leading to LPA-induced Egr-1 expression. Our data demonstrate that activation of ERK1/2 and JNK, but not p38 MAPK, is required for LPA-induced Egr-1 expression in smooth muscle cells. We provide the first evidence that MEK-mediated JNK activation leads to LPA-induced gene expression. JNK2 is required for Egr-1 induction. Examining the upstream kinases that mediate ERK and JNK activation, leading to Egr-1 expression, we found that LPA-induced activation of MAPKs and expression of Egr-1 are dependent on PKC activation. We observed that LPA rapidly activates PKCδ and PKCθ. Overexpression of dominant-negative PKCδ, but not dominant-negative PKCθ, diminished activation of ERK and JNK and blocked LPA-induced expression of Egr-1 mRNA and protein. We also evaluated LPA receptor involvement. Our data reveal an intracellular regulatory mechanism: LPA induction of Egr-1 expression is via LPA cognate receptor (LPA receptor 1)-dependent and PKCδ-mediated ERK and JNK activation. This study provides the first evidence that PKCδ mediates ERK and JNK activation in the LPA signaling pathway and that this pathway is required for LPA-induced gene regulation as evidenced by Egr-1 expression.

Introduction

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)2 is produced by activated platelets (1) and is formed in oxidized LDL (2). High concentrations of LPA have been found in human atherosclerotic lesions (2) and human serum (1, 3). Accumulated evidence indicates that LPA influences vascular cell functions, including smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation, migration, and dedifferentiation, which are controlled by LPA-induced gene expression (for review, see Ref. 4).

Previously, we have shown that LPA markedly induces Egr-1 (early growth response gene-1) expression in vascular SMCs (5). Egr-1, a zinc finger transcription factor, activates a set of genes implicated in the pathogenesis of restenosis and atherosclerosis with subsequent thrombosis. The products of these genes include proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, growth factors, coagulation factors, and matricellular modulators, such as tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-2, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, CD44, platelet-derived growth factor A- and B-chains, fibroblast growth factor-2, transforming growth factor-β1, tissue factor, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, urokinase-type plasminogen activator, 5-lipoxygenase, thrombospondin, and metalloproteinases (6, 7). Thus, Egr-1 plays a vital role in regulating the expression of a set of important genes, leading to vascular diseases. An important step toward understanding the mechanism of vascular diseases is understanding the intracellular mechanism by which Egr-1 expression is regulated in vascular cells in response to lipid mediators that are accumulated in the vascular environment. In a previous study, we demonstrated that transcriptional regulation controls LPA-induced egr-1 gene expression and that both the cAMP response element and serum response element motifs of the egr-1 promoter are required for LPA-induced egr-1 promoter activation (5). In the present study, we sought to determine the intracellular signaling pathway leading to LPA-induced Egr-1 expression. Our results demonstrate the roles of LPA receptors and the specific PKC and MAPK in regulation of Egr-1 expression in vascular SMCs. We discovered several previously unrevealed intracellular molecular links in the LPA signaling pathway and their functions in LPA-induced gene expression.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

LPA (1-oleoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphate) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Phosphate buffer was from Sigma-Aldrich. TRIzol reagent and the ThermoScript RT-PCR system were from Invitrogen. The RNeasy kit was from Qiagen. GeneAmp PCR core reagents were from Applied Biosystems. [32P]dCTP was from MP Biochemicals (Solon, OH). The DNA labeling kit was from GE Healthcare. U0126, SB203580, SP600125, GF109203X, rottlerin, and Ki16425 were from BIOMOL International (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Antibodies against phospho-MEK, phospho-ERK, phospho-p38, phospho-JNK, phospho-PKCα (Ser-657), phospho-PKCα/βII (Thr-638/Thr-641), pan-phospho-PKCβII (Ser-660), phospho-PKCδ (Tyr-311), phospho-PKCϵ (Ser-729), phospho-PKCζ/λ (Thr-410/Thr-403), phospho-PKCθ (Thr-538), JNK1, JNK2, JNK3, and PKD/PKCμ were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). The antibody against Egr-1 was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), and antibodies against PKCδ and PKCθ were from BD Transduction Laboratories. Primers of rat LPA receptors used in conventional PCR and real-time PCR were from Operon Technologies (Alameda, CA). For conventional PCR, the following primers were used: LPA receptor 1 (LPA1), AGC TGC CTC TAC TTC CAG C (forward primer) and TTG CTG TGA ACT CCA GCC AG (reverse primer); LPA2, CCT ACC TCT TCC TCA TGT TC (forward primer) and TAA AGG GTG GAG TCC ATC AG (reverse primer); and LPA3, GGC AAG CGG ATG GAC TTT (forward primer) and CAT GTC CTC GTC CTT GTA CG (reverse primer). For real-time PCR, the following primers were used: LPA1, ATC ACT GTC TGC GTG TTC ATC AT (forward primer) and ATG GAA GCG GCG GTT GA (reverse primer); LPA2, GGT AGC CGT CTA CAC ACG AAT TTT (forward primer) and GCT CTG CCA TGC GTT CAA (reverse primer); LPA3, GGA AGT TCC ACT TTC CCT TCT ACT AC (forward primer) and GCG ATT CCG GCA AAG AAA T (reverse primer); and β-actin, CAC CCG CGA GTA CAA CCT TC (forward primer) and CCC ATA CCC ACC ATC ACA CC (reverse primer).

Tissue Culture

SMCs were prepared from explants of excised aortas of rats as described previously (8). Cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were made quiescent by incubation in serum-free DMEM for 48 h. LPA was dissolved in PBS, and a final concentration of 25 μm was used.

Northern Blot Analysis

Total cellular RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA (6–8 μg) was subjected to denaturing electrophoresis on formaldehyde-agarose gels. RNA was blotted onto Nytran membranes (Schleicher & Schüll) and hybridized with radiolabeled cDNA probes as described previously (5).

Western Blot Analysis

Rat SMCs were rinsed with cold PBS and lysed in Western blot lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 8 m urea, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, and protease inhibitors) with sonication for 20 s on ice. Cellular proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore). Membranes were then probed with the specific antibodies, and the specific protein bands were visualized by ECL Plus (GE Healthcare).

Adenoviral Constructs and Adenoviral Infection of SMCs

Adenoviruses encoding PKCθ were constructed as previously described (9). Adenoviral wild-type and dominant-negative PKCδ constructs were kindly provided by Dr. Motoi Ohba (Showa University, Tokyo, Japan). SMCs in DMEM containing 10% FBS were infected for 24 h with either wild-type or dominant-negative PKC isotypes.

Conventional RT-PCR Assay

Expression of LPA receptor mRNA was evaluated by RT-PCR. Total RNA was isolated from SMCs using an RNeasy mini-prep kit (Qiagen). The first strand of cDNA was reverse-transcribed using the ThermoScript RT-PCR system. The cDNA products were amplified using GeneAmp PCR core reagents. The amplification conditions were as follows: 2 min at 95 °C; 25–31 cycles for 45 s at 95 °C, 45 s at 55 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C; followed by a final extension for 5 min at 72 °C. The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1.0% agarose gel.

Real-time PCR Assay

The primers were designed using Primer Express 3.0 software (Applied Biosystems). Real-time PCR was performed on an ABI 7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) under the following conditions: 95 °C for 10 min and 40 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min.

siRNA Treatment

Cells were transfected with non-silencing, JNK1, or JNK2 siRNA (Qiagen) for 48 h using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen) following the instructions provided by the manufacturer. On day 3, cells were starved for 24 h prior to LPA treatment.

Statistical Analysis

The means ± S.E. were calculated using Excel statistical Software, and statistical significance (p value) was determined by Student's two-tailed t test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Activation of ERK and JNK MAPKs Is Required for LPA-induced Egr-1 Expression

We previously demonstrated that a transcriptional mechanism controls LPA-induced egr-1 gene expression (5). Our results further showed that nuclear serum response factor (SRF) and cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) mediate LPA-induced egr-1 gene transcription in SMC nuclei (5). However, the upstream intracellular signaling pathway, which leads to LPA-induced Egr-1 expression, has been elusive. To first determine whether MAPKs are involved in LPA-induced Egr-1 expression, we measured LPA-induced MAPK activation. Rat SMCs were starved for 48 h prior to LPA treatment. At various time points of LPA treatment, SMCs were washed with PBS and lysed for the detection of intracellular phosphorylation of various MAPKs: ERK, JNK, and p38 MAPK. As shown in Fig. 1A, LPA markedly and transiently induced activation of ERK kinase (MEK), ERK, JNK, and p38 MAPK in SMCs. The activation peaks of these kinases in SMCs by LPA were at ∼2–5 min.

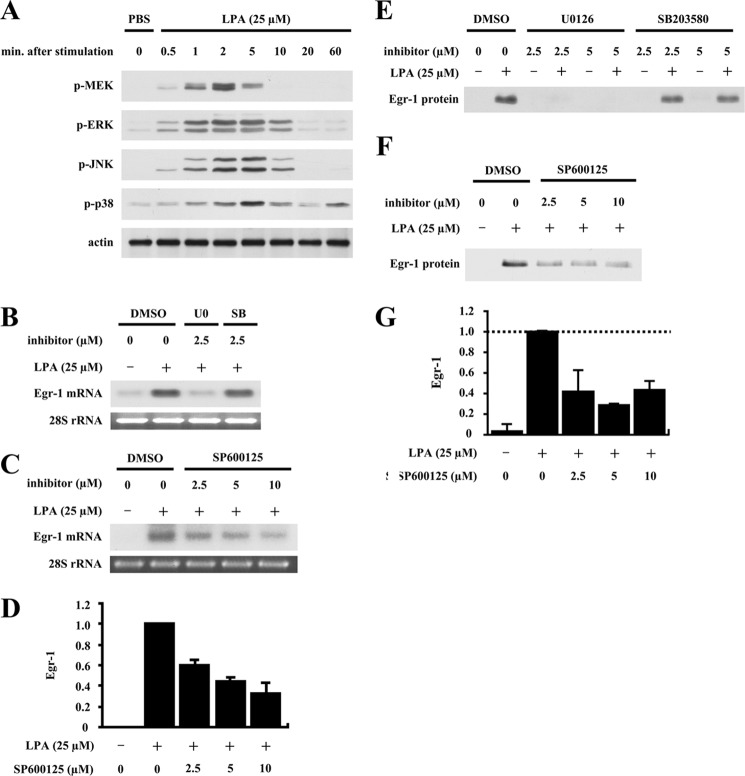

FIGURE 1.

Roles of ERK, JNK, and p38 MAPKs in LPA-induced Egr-1 expression. A, dynamic activation of MAPKs in vascular SMCs in response to LPA stimulation. Starved rat aortic SMCs were stimulated with LPA (25 μm) for various times. Phosphorylation of MAPKs was detected by Western blotting. Because LPA was dissolved in PBS, PBS was used as a system control. β-Actin was used as a loading control (Ctr). B, effect of U0126 or SB203580 on LPA-induced Egr-1 mRNA accumulation. SMCs were pretreated with U0126 (U0) or SB203580 (SB) at 2.5 μm for 40 min, followed by LPA stimulation for 30 min. Egr-1 mRNA expression was detected by Northern blot analysis using 32P-labeled rat Egr-1 cDNA fragments. Because U0126 or SB203580 was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), a sample treated with dimethyl sulfoxide alone served as a control. 28 S rRNA was used as a loading control. C, effect of SP600125 on LPA-induced Egr-1 mRNA expression. SMCs were pretreated with various doses of SP600125 for 40 min and then stimulated with LPA for 30 min. Egr-1 mRNA expression was determined by Northern blot analysis. Conditions were as described for B. D, the results of the Northern blot analysis were quantified by densitometry. Data are means ± S.E. from three experiments (p < 0.01, each SP600125 + LPA sample versus LPA-alone sample). E, effect of U0126 or SB203580 on LPA-induced Egr-1 protein expression. SMCs were pretreated with U0126 or SB203580 at various doses as indicated for 40 min, and cells were then stimulated with LPA for 1 h. Egr-1 protein synthesis was detected by Western blot analysis. F, effect of SP600125 on LPA-induced Egr-1 protein expression. SMCs were pretreated with SP600125 at various doses for 40 min, followed by LPA treatment for 1 h. Egr-1 protein expression was detected by Western blot analysis. G, the results of Western blot analysis were quantified by densitometry. Data are means ± S.E. from three experiments (p < 0.01, each SP600125 + LPA sample versus LPA-alone sample).

To determine which of these kinases are involved in LPA-induced Egr-1 expression, we tested whether pretreatment with the ERK kinase (MEK) inhibitor U0126, p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580, or JNK inhibitor SP600125 had any effect on LPA-induced Egr-1 expression. As shown in Fig. 1B, pretreatment of SMCs with 2.5 μm U0126, but not with 2.5 μm SB203580, completely blocked LPA-induced Egr-1 mRNA expression. SP600125 dose-dependently blocked LPA-induced Egr-1 mRNA (Fig. 1, C and D). These data show that activation of MEK/ERK and JNK is required, but p38 does not play a role in LPA-induced egr-1 gene expression in SMCs. We next evaluated the effects of these specific inhibitors on LPA-induced Egr-1 protein synthesis. Consistent with the data shown in Fig. 1 (B–D), pretreatment of cells with 2.5 and 5.0 μm U0126 completely blocked LPA-induced Egr-1 protein expression; however, SB203580 at two effective doses (2.5 and 5.0 μm) had no effect on LPA-induced Egr-1 protein synthesis (Fig. 1E). We also observed that SP600125 dose-dependently blocked Egr-1 protein expression (Fig. 1, F and G). These results indicate that LPA activation of MEK/ERK and JNK is required for Egr-1 protein expression, whereas p38 MAPK does not have a role. Therefore, the data shown in Fig. 1 demonstrate that LPA-induced Egr-1 expression depends on the MEK/ERK and JNK cascades.

PKC Mediates MAPK Activation, Leading to LPA-induced Egr-1 Expression

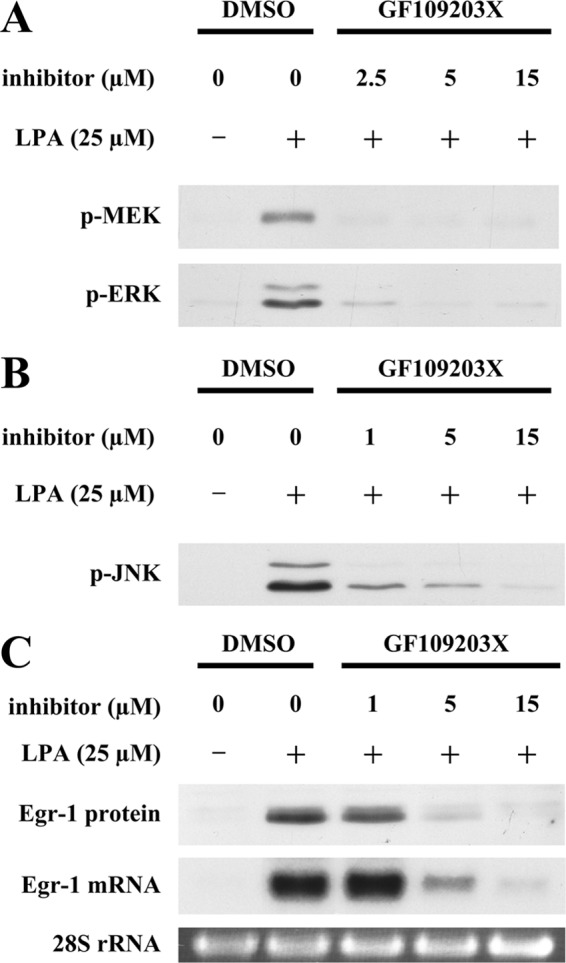

To search for the upstream intracellular mediator that controls ERK and JNK MAPK activation, leading to LPA-induced Egr-1 expression, we examined the role of PKC in MAPK activation and Egr-1 synthesis. Pretreatment of SMCs with the general PKC inhibitor GF109203X dose-dependently blocked LPA-induced activation of MEK, ERK, and JNK (Fig. 2, A and B), as well as LPA-induced expression of Egr-1 mRNA and protein (Fig. 2C). These results indicate that PKC-mediated activation of MEK/ERK and JNK leads to LPA induction of Egr-1 expression.

FIGURE 2.

Role of PKC in LPA-induced ERK and JNK activation and Egr-1 expression. Starved SMCs were pretreated with GF109203X at various doses for 40 min, and cells were then stimulated with LPA for 5 min for analysis of MAPK phosphorylation, for 30 min for analysis of Egr-1 mRNA accumulation, and for 1 h for analysis of Egr-1 protein accumulation. A, phosphorylation of MEK and ERK was detected by Western blot analysis. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide. B, phosphorylation of JNK was examined by Western blot analysis. C, expression of Egr-1 mRNA and protein was examined by Northern and Western analyses. 28 S rRNA was used as a loading control.

Specific PKC Isotypes Are Involved in LPA Induction of Egr-1 Expression in SMCs

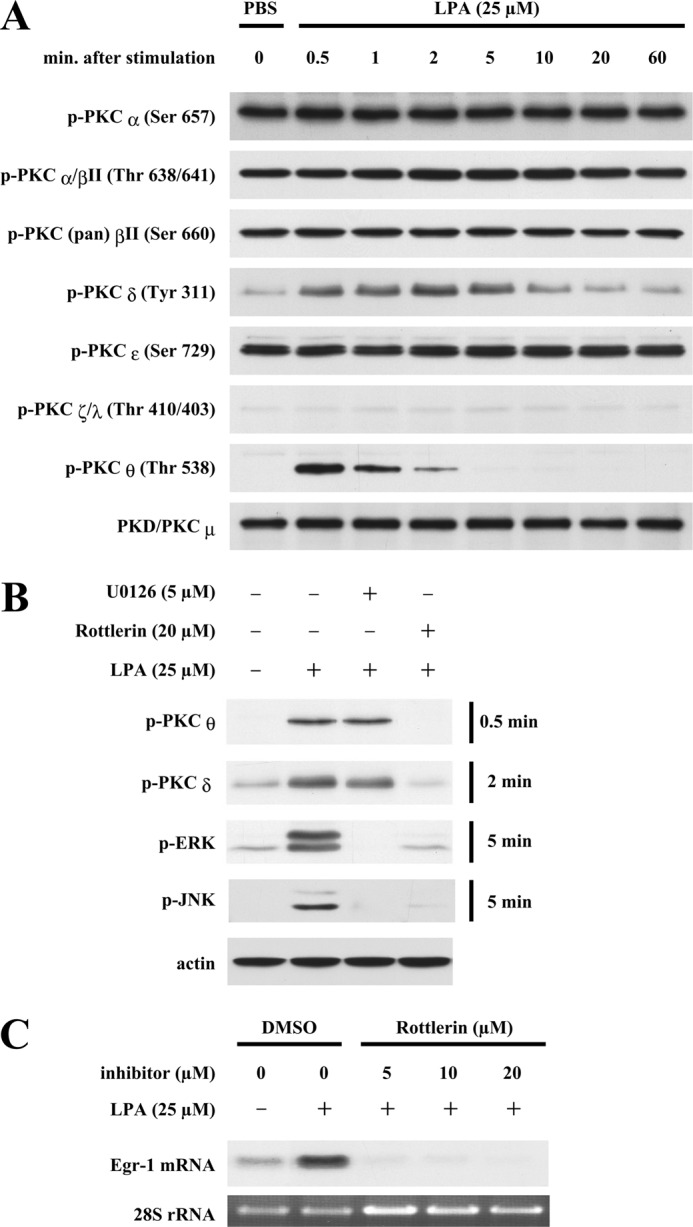

To determine the specific PKC isotype function in LPA induction of Egr-1 expression, we evaluated activation of specific PKC isotypes in SMCs in response to LPA stimulation. As shown in Fig. 3A, PKCδ and PKCθ were activated very rapidly and markedly by LPA, with phosphorylation peaks at ∼30 s and 2 min. However, there was no significant phosphorylation detected for other isotypes of PKC in response to LPA (Fig. 3A), suggesting that novel PKC group members PKCδ and PKCθ may be involved in LPA-induced Egr-1 expression.

FIGURE 3.

Preliminary evaluation of PKC involvement in LPA-induced MAPK activation and Egr-1 expression. A, dynamic phosphorylation of PKCs in SMCs in response to LPA stimulation. Starved SMCs were stimulated with LPA for various time periods as indicated. Phosphorylation of various PKC isotypes was detected by Western blot analysis using specific antibodies against various phosphorylated sites of PKC isotypes. Expression of PKCμ served as an internal control. B, effect of U0126 or rottlerin on LPA-induced phosphorylation of PKCδ, PKCθ, ERK, and JNK. SMCs were pretreated with U0126 and rottlerin for 40 min, and cells were then treated with LPA for various time periods as indicated. Phosphorylation of PKCδ, PKCθ, ERK, and JNK was examined by Western blot analysis. β-Actin served as a loading control. C, effect of rottlerin on LPA induction of Egr-1 expression. SMCs were pretreated with rottlerin at various doses for 40 min, and cells were then stimulated with LPA for 30 min. Egr-1 mRNA expression was detected by Northern blot analysis. 28 S rRNA served as a loading control. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

We next tested the roles of PKCδ and PKCθ in Egr-1 expression using the pharmacological compound rottlerin, which has been reported to inhibit the activity of PKCθ (10) and PKCδ (11). As shown in Fig. 3B, pretreatment of SMCs with 20 μm rottlerin completely blocked LPA-induced phosphorylation of PKCθ, PKCδ, ERK, and JNK, suggesting that activation of PKCθ and PKCδ may be involved in ERK and JNK activation. Conversely, in a reciprocal experiment, we tested whether ERK activation has a feedback effect on activation of PKCθ and PKCδ or has a role in activation of PKCθ and PKCδ. Our results show that 5 μm U0126, a specific MEK inhibitor, completely blocked activation of ERK, a substrate of MEK, but had no effect on phosphorylation of PKCθ and PKCδ (Fig. 3B), indicating that MEK and ERK are not the upstream regulators of either PKCθ or PKCδ and do not have an effect on activation of PKCθ and PKCδ. Furthermore, we observed that rottlerin at a low dose of 5 μm completely inhibited LPA-induced Egr-1 mRNA expression (Fig. 3C). Together, these data support the possibility that LPA-induced activity of PKCθ and PKCδ may regulate activation of their downstream molecules ERK and JNK, leading to Egr-1 expression.

MEK/ERK-regulated JNK Activation Leads to LPA-induced Gene Expression in Vascular SMCs

LPA activation of MAPK in various cell types has been reported (12–15); however, the cross-talk between individual MAPK family members in LPA signaling is not well documented compared with that in growth factor signaling. Especially, MEK/ERK-regulated JNK activation in LPA signaling that leads to LPA induction of gene expression has not been revealed. We observed that U0126 at a low dose of 5 μm completely blocked activation of ERK (a substrate of MEK) and JNK, indicating that MEK/ERK activation is required for LPA-induced JNK phosphorylation and activation (Fig. 3B). This result, together with the results shown in Fig. 1, indicates that MEK/ERK-regulated JNK activation leads to LPA-induced gene expression. To the best of our knowledge, these data document that the cross-talk between the MEK/ERK pathway and the JNK pathway in LPA signaling contributes to LPA-induced gene expression as evidenced by Egr-1 expression.

PKCδ, but Not PKCθ, Activates ERK and JNK, Leading to Egr-1 Expression

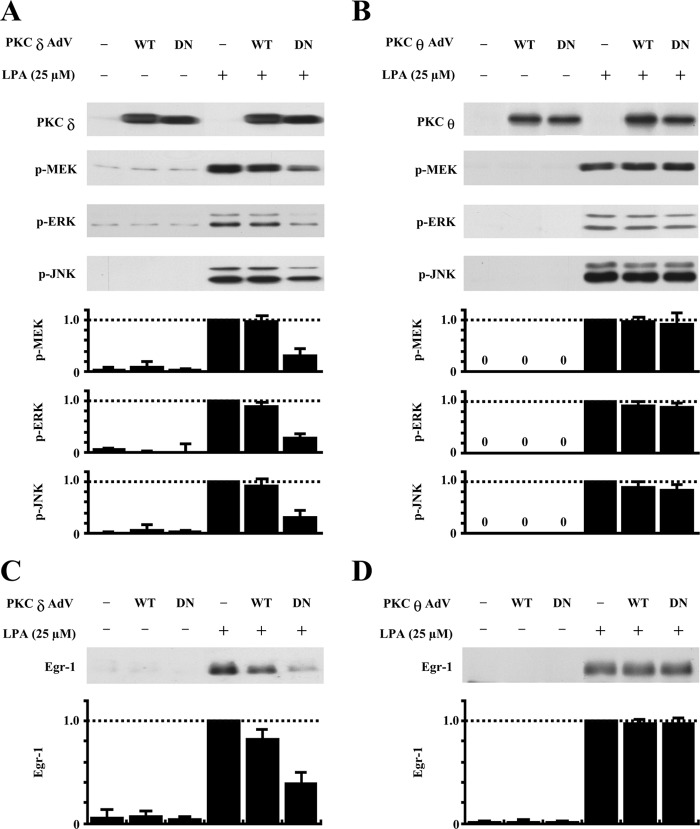

Because the pharmacological compound rottlerin has an inhibitory effect on PKCθ (10) and PKCδ (11) and also considering the possible nonspecific effect of this pharmacological inhibitor, we further evaluated whether and which novel PKC mediates Egr-1 expression via activation of ERK and JNK by employing a dominant-negative approach. We determined the effect of overexpression of dominant-negative PKCδ in adenovirus on activation of ERK and JNK in SMCs as well as on expression of Egr-1 in comparison with the effect of dominant-negative PKCθ. In these experiments, we included wild-type PKCδ or PKCθ as a control. As shown in Fig. 4A, overexpression of dominant-negative PKCδ in SMCs significantly blocked LPA-induced activation of MEK, ERK, and JNK. In contrast, overexpression of dominant-negative PKCθ had no effect on activation of MEK, ERK, and JNK induced by LPA (Fig. 4B). We also observed that neither wild-type PKCδ nor wild-type PKCθ had a significant effect on MAPK activation (Fig. 4, A and B). These results indicate that activated PKCδ, but not activated PKCθ, is required for LPA-induced MEK, ERK, and JNK activation. We next evaluated the effects of dominant-negative PKCδ and dominant-negative PKCθ on Egr-1 expression. As shown in Fig. 4 (C and D), we found that overexpression of dominant-negative PKCδ, but not dominant-negative PKCθ, markedly blocked Egr-1 expression. Overexpression of wild-type PKCδ and PKCθ had no significant effect on Egr-1 expression (Fig. 4, C and D). Therefore, the results shown in Fig. 4 support the conclusion that LPA signaling leads to intracellular activation of both PKCδ and PKCθ, but only activated PKCδ, and not PKCθ, is required for MEK/ERK and JNK activation, which in turn, mediates Egr-1 expression.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of overexpression of dominant-negative and wild-type PKCδ and PKCθ on LPA phosphorylation of MAPKs and Egr-1 expression. A, effect of overexpression of dominant-negative or wild-type PKCδ on LPA-induced MAPK phosphorylation. SMCs were infected with wild-type (WT) and dominant-negative (DN) PKCδ adenoviruses (AdV) for 24 h, followed by LPA treatment for 5 min. Expression of PKCδ protein and phosphorylation of MEK, ERK, and JNK were detected by Western blot analyses (upper panels). The results of Western blot analyses were quantified by densitometry (lower panels). Data are means ± S.E. from three experiments (p < 0.01, dominant-negative PKCδ plus LPA versus LPA alone). B, effect of overexpression of dominant-negative or wild-type PKCθ on LPA-induced MAPK phosphorylation. SMCs were infected with wild-type and dominant-negative PKCθ adenoviruses for 24 h, followed by LPA treatment for 5 min. Expression of PKCθ protein and phosphorylation of MEK, ERK, and JNK were detected by Western blot analyses (upper panels). The results of Western blot analyses were quantified by densitometry (lower panels). Data are means ± S.E. from three experiments. C, effect of overexpression of dominant-negative or wild-type PKCδ on LPA induction of Egr-1 protein expression. Upper panel, the level of Egr-1 protein 1 h after LPA stimulation was examined by Western blot analysis. Lower panel, the results of Western blot analyses were quantified by densitometry. Data are means ± S.E. from three experiments (p < 0.05, dominant-negative PKCδ plus LPA versus LPA alone). Conditions were as described for A and B. D, effect of overexpression of dominant-negative or wild-type PKCθ on LPA induction of Egr-1 protein expression. Upper panel, the level of Egr-1 protein at 1 h after LPA stimulation was examined by Western blot analysis. Lower panel, the results of Western blot analyses were quantified by densitometry. Data are means ± S.E. from three experiments. Conditions were as described for A and B.

JNK2 Is Required for LPA-induced Egr-1 Expression in SMCs

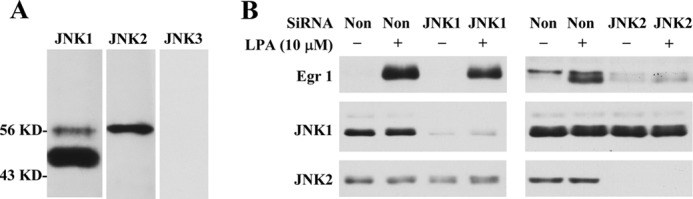

We found that the JNK inhibitor SP600125 dose-dependently blocked LPA-induced Egr-1 expression (Fig. 1, C, D, F, and G) and that ERK kinase (MEK) inhibitor U0126 completely blocked JNK activation (Fig. 3B) and Egr-1 expression (Fig. 1, B and E). These results indicate that MEK-mediated JNK activation is required for LPA-induced Egr-1 expression. To confirm the JNK role in LPA-induced Egr-1 expression, we determined the isoforms of JNK expressed in rat SMCs and their functions in Egr-1 expression. As shown in Fig. 5A, JNK1 and JNK2, but not JNK3, were expressed in SMCs. We next tested whether knockdown of either JNK1 or JNK2 affects LPA-induced Egr-1 expression. Our results show that knockdown of JNK2, but not JNK1, blocked Egr-1 expression (Fig. 5B), indicating that JNK2 is required for the LPA signaling pathway leading to Egr-1 expression.

FIGURE 5.

JNK2 is required for LPA-induced Egr-1 expression in SMCs. A, Western analysis of expression of JNK isoforms. B, effect of knockdown of JNK1 or JNK2 on LPA-induced Egr-1 expression (Western analysis). Non-silencing RNA (non) was used as a control. Treatment conditions were described under “Experimental Procedures.” Egr-1 expression was measured after LPA treatment for 1 h. Knockdown efficiency was determined using the specific antibodies against JNK1 and JNK2.

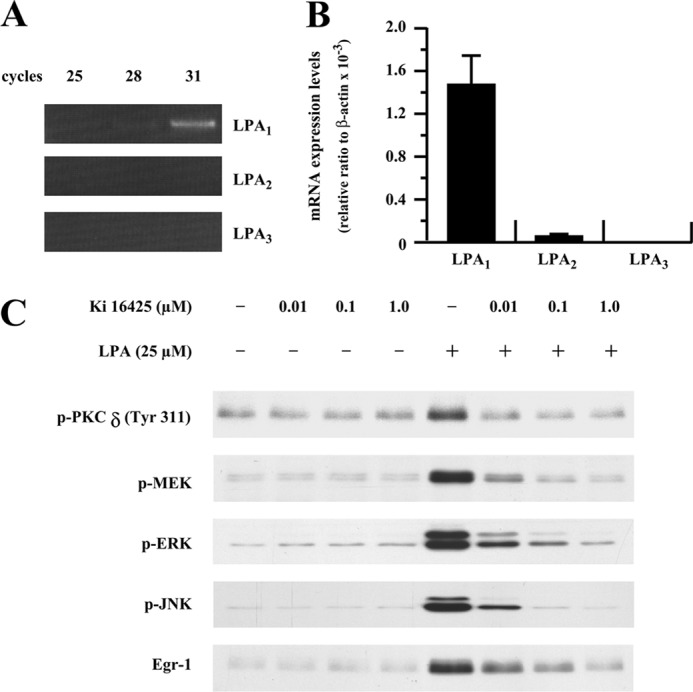

LPA1 Is the Main Receptor Responsible for LPA-induced Egr-1 Expression

LPA is known to mediate gene expression via its cognate G-protein-coupled receptors. Thus far, at least five G-protein-coupled LPA receptors have been reported (16). LPA1, LPA2, and LPA3 share very high homology (16). To determine which LPA receptors mediate the LPA signal leading to Egr-1 expression in SMCs, we performed RT-PCR analyses in various reaction cycles (25–31 cycles) to determine LPA receptor expression levels. As shown in Fig. 6A, we found that LPA1 was expressed predominantly in rat SMCs. The relative abundance of the receptors was determined by real-time PCR analysis with the following ratio: LPA1 ≫ LPA2 > LPA3 (Fig. 6B). To evaluate the role of the predominant form, LPA1, in LPA-induced kinase activation and Egr-1 expression, we pretreated SMCs with various doses of Ki16425, a potent inhibitor of LPA1 and LPA3. As shown in Fig. 6C, pretreatment with Ki16425 dose-dependently blocked activation of PKCδ, MEK, ERK, and JNK and expression of Egr-1, indicating that LPA1 is the major LPA receptor on the plasma membrane that mediates the LPA signal leading to the intracellular activation of PKCδ, which then activates the ERK and JNK pathways, leading to Egr-1 transcription in the nuclei of SMCs.

FIGURE 6.

LPA1 is mainly responsible for LPA-induced Egr-1 expression. A, expression profiles of LPA receptors in SMCs (conventional RT-PCR results). Total RNA of SMCs was extracted, and expression of LPA1, LPA2, and LPA3 was measured by RT-PCR for various cycles as indicated. B, relative abundance of LPA receptors. Real-time PCR assay was performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” C, SMCs were pretreated for 40 min with LPA1/LPA3 antagonist Ki16425 at various doses as indicated, and the cells were then treated with LPA for 2 min for PKCδ phosphorylation, 5 min for MAPK activation, and 1 h for Egr-1 protein analysis. Expression of Egr-1 protein and phosphorylation of PKCδ, MEK, ERK, and JNK were detected by Western blot analyses.

DISCUSSION

LPA, a bioactive phospholipid produced by activated platelets, has been found to accumulate at high concentrations in atherosclerotic lesions. LPA is formed during the oxidation of LDL (2). Evidence has shown that accumulation of this lipid mediator may serve as an important risk factor for development of atherosclerosis and thrombosis (4). LPA affects many functions of various vascular cells through mediating the expression of a variety of genes in these cells. In vascular SMCs, LPA induces expression of several genes, such as the coagulation initiator tissue factor (15), IL-6 (14), monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (17), and Egr-1 (5). Among these genes, Egr-1 is a nuclear transcription factor that reportedly mediates expression of monocyte chemotactic protein-1, IL-6, and tissue factor (18–22), all of which are known to play important roles in the development of atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Therefore, understanding the intracellular signaling pathway leading to expression of the key regulatory transcription factor Egr-1 is essential to understanding how to prevent activation of the Egr-1 pathway and how to minimize the effect of Egr-1 and its downstream target gene products and ultimately to reduce atherogenesis and thrombosis.

In this study, we focused on understanding the intracellular signaling cascade in LPA-stimulated Egr-1 expression in primary rat SMCs. Our data reveal an essential intracellular signaling cascade in the mediation of the LPA signal leading to Egr-1 up-regulation. We demonstrated that LPA via its cognate receptor LPA1 activates PKCδ, which in turn mediates activation of MEK/ERK and JNK, leading to Egr-1 transcription and translation.

Previously, we established that the transcriptional regulation mechanism controls LPA-induced egr-1 gene expression (5). We showed that LPA regulates Egr-1 expression via transcription factors CREB and SRF, which bind to the cis-acting cAMP response element and serum response element in the egr-1 promoter region. These results established a novel role for CREB in mediating LPA-induced gene expression. Additionally, we also showed that LPA-induced protein-DNA binding activity is caused by LPA-induced rapid phosphorylation of CREB and SRF.

In this study, performed to determine the intracellular regulatory mechanism upstream of Egr-1 transcription, our data reveal an essential role for PKCδ in LPA-induced Egr-1 expression. To our knowledge, although LPA signaling has been widely studied, the role of PKCδ in LPA-induced gene expression has been largely unknown. We observed a rapid activation of both PKCδ and PKCθ in vascular SMCs in response to LPA stimulation. Rottlerin, an inhibitor of both PKCδ and PKCθ (10, 11), blunted LPA induction of Egr-1, suggesting that PKCδ, PKCθ, or both may be involved in Egr-1 expression. However, our approach using overexpression of dominant-negative PKCδ or PKCθ defined PKCδ, but not PKCθ, as the essential regulator mediating the LPA signal leading to Egr-1 expression.

Our data further demonstrate that an essential role for PKCδ in LPA-induced Egr-1 expression is via the MEK/ERK-regulated JNK pathway. To date, LPA activation of PKC, MAPK, or PKC/MAPK in various cell types (12–14, 23), LPA activation of PKCδ (24, 25), and PKCδ regulation of IL-8 expression in bronchial epithelial cells (25, 26), as well as ERK involvement in LPA-induced Egr-1 expression (27), have been reported. However, the regulatory relationship between PKCδ and MAPK in the LPA signaling pathway has not been documented. Furthermore, the functional role of PKCδ-activated MAPK in LPA signaling has not been revealed. In this study, our data not only demonstrate that PKCδ mediates activation of MEK/ERK and JNK, but also reveal the functional role of the PKCδ-mediated MEK/ERK and JNK cascade that up-regulates the egr-1 gene. Therefore, these data provide the first evidence of PKCδ regulation of MAPK in the LPA signaling pathway and reveal for the first time that PKCδ-regulated MAPK (ERK and JNK) leads to LPA-induced gene expression in living cells, i.e. LPA induction of Egr-1 expression is mediated by the PKCδ-activated MAPK (ERK and JNK) pathway. In addition, our data demonstrate that the cross-talk between the MEK/ERK and JNK pathways contributes to LPA-induced gene expression. JNK2 is required for LPA-induced Egr-1 expression.

We previously showed that LPA induces Egr-1 transcription via transactivation of the CREB and SRF transcription factors and binding of these transcription factors to the cis-elements in the egr-1 promoter in the nuclei of vascular SMCs (5). Because CREB is one of the major downstream targets of ERK1/2 (28–30) and activation of the SAPK/JNK pathway is required for activation of the chromosomal SRF-controlled reporter gene (31), it is likely that the individual ERK pathway or the MEK/ERK pathway, in conjunction with the JNK pathway, cooperatively mediates Egr-1 expression via the CREB and SRF transcription factors in the nuclei of SMCs.

It is important to note that Egr-1, a zinc finger transcription factor, plays a key master regulatory role in multiple cardiovascular pathological processes, including atherosclerosis, cardiac hypertrophy, ischemia, and angiogenesis (6), and was recently described as a major link between infection and atherosclerosis (32, 33). Our data clearly establish a signaling pathway involving LPA1 and the PKCδ-activated MAPK (ERK and JNK) cascade in regulating LPA induction of Egr-1 synthesis. These results provide new insights into the cellular mechanisms by which LPA exerts its effects in SMCs. The identified intracellular molecules involved in the LPA signaling pathway that leads to the up-regulation of Egr-1 may serve as therapeutic targets in the management of vascular disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Misty Bailey for critical reading of the manuscript and Dr. Motoi Ohba for providing PKCδ constructs.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HL074341 and HL107466 (to M.-Z. C.) and AG026640 (to X. X.).

- LPA

- lysophosphatidic acid

- SMC

- smooth muscle cell

- LPA1

- LPA receptor 1

- SRF

- serum response factor

- CREB

- cAMP response element-binding protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Eichholtz T., Jalink K., Fahrenfort I., Moolenaar W. H. (1993) The bioactive phospholipid lysophosphatidic acid is released from activated platelets. Biochem. J. 291, 677–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siess W., Zangl K. J., Essler M., Bauer M., Brandl R., Corrinth C., Bittman R., Tigyi G., Aepfelbacher M. (1999) Lysophosphatidic acid mediates the rapid activation of platelets and endothelial cells by mildly oxidized low density lipoprotein and accumulates in human atherosclerotic lesions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 6931–6936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baker D. L., Desiderio D. M., Miller D. D., Tolley B., Tigyi G. J. (2001) Direct quantitative analysis of lysophosphatidic acid molecular species by stable isotope dilution electrospray ionization liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 292, 287–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cui M. Z. (2011) Lysophosphatidic acid effects on atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Clin. Lipidol. 6, 413–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cui M. Z., Laag E., Sun L., Tan M., Zhao G., Xu X. (2006) Lysophosphatidic acid induces early growth response gene-1 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells: CRE and SRE mediate the transcription. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26, 1029–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khachigian L. M. (2006) Early growth response-1 in cardiovascular pathobiology. Circ. Res. 98, 186–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blaschke F., Bruemmer D., Law R. E. (2004) Egr-1 is a major vascular pathogenic transcription factor in atherosclerosis and restenosis. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 5, 249–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brock T. A., Alexander R. W., Ekstein L. S., Atkinson W. J., Gimbrone M. A., Jr. (1985) Angiotensin increases cytosolic free calcium in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension 7, I105–I109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cazzolli R., Craig D. L., Biden T. J., Schmitz-Peiffer C. (2002) Inhibition of glycogen synthesis by fatty acid in C2C12 muscle cells is independent of PKCα, PKCϵ, and PKCθ. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 282, E1204–E1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Springael C., Thomas S., Rahmouni S., Vandamme A., Goldman M., Willems F., Vosters O. (2007) Rottlerin inhibits human T cell responses. Biochem. Pharmacol. 73, 515–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gschwendt M., Müller H. J., Kielbassa K., Zang R., Kittstein W., Rincke G., Marks F. (1994) Rottlerin, a novel protein kinase inhibitor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 199, 93–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Howe L. R., Marshall C. J. (1993) Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates mitogen-activated protein kinase activation via a G-protein-coupled pathway requiring p21ras and p74raf-1. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 20717–20720 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hordijk P. L., Verlaan I., van Corven E. J., Moolenaar W. H. (1994) Protein tyrosine phosphorylation induced by lysophosphatidic acid in Rat-1 fibroblasts. Evidence that phosphorylation of MAP kinase is mediated by the Gi-p21ras pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 645–651 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hao F., Tan M., Wu D. D., Xu X., Cui M. Z. (2010) LPA induces IL-6 secretion from aortic smooth muscle cells via an LPA1-regulated, PKC-dependent, and p38α-mediated pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 298, H974–H983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cui M. Z., Zhao G., Winokur A. L., Laag E., Bydash J. R., Penn M. S., Chisolm G. M., Xu X. (2003) Lysophosphatidic acid induction of tissue factor expression in aortic smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23, 224–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chun J., Hla T., Lynch K. R., Spiegel S., Moolenaar W. H. (2010) International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXVIII. Lysophospholipid receptor nomenclature. Pharmacol. Rev. 62, 579–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kaneyuki U., Ueda S., Yamagishi S., Kato S., Fujimura T., Shibata R., Hayashida A., Yoshimura J., Kojiro M., Oshima K., Okuda S. (2007) Pitavastatin inhibits lysophosphatidic acid-induced proliferation and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in aortic smooth muscle cells by suppressing Rac-1-mediated reactive oxygen species generation. Vascul. Pharmacol. 46, 286–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ohtani K., Egashira K., Usui M., Ishibashi M., Hiasa K. I., Zhao Q., Aoki M., Kaneda Y., Morishita R., Takeshita A. (2004) Inhibition of neointimal hyperplasia after balloon injury by cis-element “decoy” of early growth response gene-1 in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Gene Ther. 11, 126–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Prince J. M., Ming M. J., Levy R. M., Liu S., Pinsky D. J., Vodovotz Y., Billiar T. R. (2007) Early growth response-1 mediates the systemic and hepatic inflammatory response initiated by hemorrhagic shock. Shock 27, 157–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cui M. Z., Parry G. C., Oeth P., Larson H., Smith M., Huang R. P., Adamson E. D., Mackman N. (1996) Transcriptional regulation of the tissue factor gene in human epithelial cells is mediated by Sp1 and Egr-1. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 2731–2739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cui M. Z., Penn M. S., Chisolm G. M. (1999) Native and oxidized low density lipoprotein induction of tissue factor gene expression in smooth muscle cells is mediated by both Egr-1 and Sp1. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 32795–32802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mechtcheriakova D., Wlachos A., Holzmüller H., Binder B. R., Hofer E. (1999) Vascular endothelial cell growth factor-induced tissue factor expression in endothelial cells is mediated by Egr-1. Blood 93, 3811–3823 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Corven E. J., Groenink A., Jalink K., Eichholtz T., Moolenaar W. H. (1989) Lysophosphatidate-induced cell proliferation: identification and dissection of signaling pathways mediated by G-proteins. Cell 59, 45–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Budnik L. T., Mukhopadhyay A. K. (2002) Lysophosphatidic acid-induced nuclear localization of protein kinase Cδ in bovine theca cells stimulated with luteinizing hormone. Biol. Reprod. 67, 935–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cummings R., Zhao Y., Jacoby D., Spannhake E. W., Ohba M., Garcia J. G., Watkins T., He D., Saatian B., Natarajan V. (2004) Protein kinase Cδ mediates lysophosphatidic acid-induced NF-κB activation and interleukin-8 secretion in human bronchial epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 41085–41094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhao Y., He D., Saatian B., Watkins T., Spannhake E. W., Pyne N. J., Natarajan V. (2006) Regulation of lysophosphatidic acid-induced epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation and interleukin-8 secretion in human bronchial epithelial cells by protein kinase Cδ, Lyn kinase, and matrix metalloproteinases. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 19501–19511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reiser C. O., Lanz T., Hofmann F., Hofer G., Rupprecht H. D., Goppelt-Struebe M. (1998) Lysophosphatidic acid-mediated signal transduction pathways involved in the induction of the early-response genes prostaglandin G/H synthase-2 and egr-1: a critical role for the mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 and for Rho proteins. Biochem. J. 330, 1107–1114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vanhoutte P., Barnier J. V., Guibert B., Pagès C., Besson M. J., Hipskind R. A., Caboche J. (1999) Glutamate induces phosphorylation of Elk-1 and CREB, along with c-Fos activation, via an extracellular signal-regulated kinase-dependent pathway in brain slices. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 136–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gelain D. P., Cammarota M., Zanotto-Filho A., de Oliveira R. B., Dal-Pizzol F., Izquierdo I., Bevilaqua L. R., Moreira J. C. (2006) Retinol induces the ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation of CREB through a pathway involving the generation of reactive oxygen species in cultured Sertoli cells. Cell. Signal. 18, 1685–1694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chung W. C., Ryu S. H., Sun H., Zeldin D. C., Koo J. S. (2009) CREB mediates prostaglandin F2α-induced MUC5AC overexpression. J. Immunol. 182, 2349–2356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alberts A. S., Geneste O., Treisman R. (1998) Activation of SRF-regulated chromosomal templates by Rho family GTPases requires a signal that also induces H4 hyperacetylation. Cell 92, 475–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bea F., Puolakkainen M. H., McMillen T., Hudson F. N., Mackman N., Kuo C. C., Campbell L. A., Rosenfeld M. E. (2003) Chlamydia pneumoniae induces tissue factor expression in mouse macrophages via activation of Egr-1 and the MEK-ERK1/2 pathway. Circ. Res. 92, 394–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rupp J., Hellwig-Burgel T., Wobbe V., Seitzer U., Brandt E., Maass M. (2005) Chlamydia pneumoniae infection promotes a proliferative phenotype in the vasculature through Egr-1 activation in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 3447–3452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]