Abstract

The current research examines whether self-consciousness subscales have prognostic value in the relationship between perceived norms and drinking and if that differs among college men and women. Results indicate that self-consciousness moderates gender differences in the relationship between perceived social norms and drinking. A strong positive relationship was found between perceived norms (descriptive and injunctive) and drinking for men relative to women and this was more pronounced among individuals who were lower in public self-consciousness. Similarly, the relationship between perceived injunctive norms and drinking was significantly stronger among men than women and this was more pronounced among individuals who were higher in private self-consciousness or social anxiety. These results highlight the important influence of social factors in salient peer reference groups. This is promising information for future research attempting to identify useful indicators of candidates who would most benefit from social norms interventions. This also underscores the relevance of future norms based interventions using self-consciousness as a potential moderator of intervention efficacy.

Keywords: self-consciousness, social norms, alcohol use, campus organizations, college students

1.1 Introduction

The negative effects of heavy drinking among college students are numerous and include damaged property, poor class attendance, hangovers, trouble with authorities, injuries, and even fatalities (Hingson, Heeren, Winter, & Wechsler, 2005; Wechsler, Davenport, Dowdall, Moeykens, & Castillo, 1994; Wechsler & Isaac, 1992; Wechsler, Lee, Kuo, & Lee, 2000). Further, high percentages of non-binge drinking students who live in residence halls reported experiencing secondhand effects of their peers’ drinking (Wechsler et al., 2002). Both the primary (to the self) and secondary (to others) effects of excessive alcohol use in this highly social environment have prompted college administrators and researchers to examine the underlying causes of this high-risk behavior.

Over the years, a considerable amount of research has focused on the social attributes associated with individuals who engage in high-risk drinking, as social factors are known to play an important and distinct role in human behavior and decision making. During college, peers are the major means of support and guidance for most students, exerting greater impact on behavioral decisions than biological or familial influences (Berkowitz & Perkins, 1986; Borsari & Carey, 2001). As a result, social influences have been identified as among the strongest and most consistent predictors of heavy drinking in the college environment (Borsari & Carey, 2003; Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Larimer, 2007b; Perkins, 2002; Wood, Read, Palfai, & Stevenson, 2001).

1.1 The Social Norms Approach

One approach that relies on college student influences on one another is the social norms approach to college student drinking (Berkowitz, 2004; Perkins, 2003). This approach suggests that peers influence alcohol use both directly (i.e., explicit suggestions to drink) and indirectly (i.e., perceived norms) (Borsari & Carey, 2001; Kandel, 1985). Perceived norms are beliefs about how members of one’s social group think and act. They are typically distinguished as being of two types: descriptive norms (what people actually do; behavior) and injunctive norms (what people feel is right; attitudes). Both types of norms assist individuals in determining acceptable and unacceptable social behavior (Cialdini, Reno, & Kallgren, 1990) and have been found to be uniquely associated with drinking among college students (e.g., Neighbors, et al., 2007b).

Researchers have observed that there are consistent discrepancies between perceived and actual norms (e.g., Borsari & Carey, 2003). This discrepancy is often explained by attribution theory, which purports that students have limited knowledge about the actual behaviors and attitudes of other students. As the student observes others drinking heavily, it is assumed that such excessive use is typical, resulting in elevated norms (Perkins, 2002). As a result, overestimations of heavy drinking frequency are proposed to further increase [heavy] drinking, while underestimations of abstinence or moderate drinking presumably discourage individuals from engaging in those healthier behaviors. Perceived norms are much more powerful predictors of personal consumption than actual norms of school peers (Perkins, Haines, & Rice, 2005). Similarly, compared to their own attitudes, students consistently estimate that typical students are more comfortable with (Prentice & Miller, 1993) and more approving of (Perkins & Berkowitz, 1986) alcohol use and this too is purported to have an effect on their behavior.

1.2 Moderators of Drinking: Self-Consciousness

In addition to social influences, a variety of individual differences has been studied in tandem with alcohol consumption. It has generally been found that including various dispositional traits in the study of alcohol use may lend some predictive and explanatory value. In an attempt to predict drinking and problematic use among college students, studies have utilized such factors as vulnerability to peer pressure (Johnson, 1986), drinking motives (i.e. social, mood enhancement, conformity, coping; Cooper, 1994), personality type (Ham & Hope, 2003) and expectations about the effects of alcohol (Christiansen, Smith, Roehling, & Goldman, 1989). Self-consciousness (SC) is yet another variable of prognostic value, albeit less studied than others. Self-consciousness assesses the extent to which individuals direct attention inward or outward (Fenigstein, Scheier, & Buss, 1975). This tendency typically occurs in a non-verbal fashion and appears to be an important behavioral determinant of interaction with others. As previously noted, the acquisition of perceived norms is also often based on unspoken cues and it too is a consistent predictor of behavior. Thus there may be an association between SC, perceived norms and subsequent drinking.

The SC domain encompasses preoccupation with one’s and others’ behaviors, sensitivity to inner feelings and emotions, introspective behavior, and concerns about others’ evaluation of one’s own physical appearance and presentation (Fenigstein et al., 1975). This construct has typically been defined by three subscales. Individuals high in private SC are concerned with attending to their inner thoughts and feelings. Reflections deal with the self and are attuned to one’s needs, thoughts, wants, and ideas. Public SC refers to awareness of the self as a social object that is both influenced by, and affects others. An individual high in public SC exhibits various behaviors based on reactions of others to the self. As such, there is concern with self presentation and a strong emphasis is placed on one’s social interactions and behaviors. Social anxiety is the third subscale and refers to a general discomfort felt in the presence of others. This may take the form of nervousness that arises in reaction to the process of self-focused attention, such as private and public SC.

Measures of SC have been employed in studies involving a variety of behaviors, including alcohol use. Early research into the effects of SC and related self-aware states on the consumption of alcohol found that alcohol interferes with the self-aware state by inhibiting processes related to the encoding of self-relevant information. By inhibiting these encoding processes, alcohol decreases the correspondence of behavior with personal standards of conduct and also decreases one’s [negative] self-evaluation of performance, which in essence, serves as a protective factor for cognitive dissonance (Hull 1981). Further research by Hull and Young (1983) supported the previous finding of alcohol as a mechanism to reduce a negative self-aware state. Subjects were randomly given success or failure feedback on an intellectual task. They then participated in a wine tasting experiment in which the amount of alcohol consumed was a function of SC and the quality of personal performance. Subjects higher in private SC who had received failure feedback drank significantly more wine than did subjects higher in private SC who received success feedback. Therefore, individuals may avoid alcohol consumption to retain a positive self-aware state, but increase alcohol consumption to reduce negative self-conscious affect. A similar finding examining this relationship with social anxiety and perceived norms was shown in a study by Neighbors and colleagues (2007a). They found that the relationship between perceived norms and drinking was stronger for male students who had higher social anxiety. This reaffirms a general consensus in alcohol research that peer influence is particularly important among males. A study by Prentice and Miller (1993) indicates that among college students, drinking is a greater part of the male social identity, relative to the female social identity. They also found that men perceive that they will be evaluated more negatively than do women if they don’t drink. Further, drinking makes up a larger part of college men’s self concept, than for women (Neighbors, Walker, & Larimer, 2003). Thus gender was included as a potential moderator in the current study with the anticipation that males will be more heavily influenced by perceived peer norms.

Research has also demonstrated how environmental factors and individual differences within a social group may yield important information affecting the drinking behavior and influences circulating in that group. Recent research focused on SC and drinking within Greek organizations (Park, Sher, & Krull, 2006). Although the authors acknowledged an over-sampling of individuals with a family history of alcoholism, their findings demonstrated that the effect of Greek membership on drunkenness frequency was moderated by private and public SC as well as by gender. Being high in private and public SC among fraternity members was found to function as a protective factor for drunkenness. However, for sorority members, higher private SC was associated with more drinking.

1.3 Limits of Previous Research

Other research pertaining to SC and alcohol has had limitations relating to population and alcohol use variables. Specifically, some college participant samples are narrow in external validity as they may not be representative of the general college population. Self-consciousness studies have used samples consisting of only first year students (Neighbors et al., 2007a), only second year students (Plüddemann, Theron, & Steel, 1999), or students enrolled in introductory psychology courses (Carver, Antoni, & Scheier, 1985; Santee & Maslach, 1982). All of these studies represent mostly under-age drinkers. Another gap in SC research involves variability in the measurement of alcohol consumption, ranging from reliable quantity-based measures (e.g. average number of drinks per drinking occasion; e.g., Hull & Young, 1983), to more precarious subjective alcohol use variables, such as frequency of ‘drunkenness’ (e.g., Park et al., 2006; Plüddemann et al.). Thus, previous research is limited by restrictive samples of convenience, discrepant measures of alcohol use, and other methodological limitations including shortening the SC scale (Plüddemann et al.).

1.4 The Current Study

The current study included a large and ethnically diverse sample, representative of both age and class year of college students, to evaluate potential moderating relationships among SC, perceived norms and alcohol use. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the moderating influence of all three SC subscales on the well-established relationship between perceived norms and drinking. In general we expected to replicate previous research indicating positive associations between perceived norms and drinking and that these relationships would be stronger among men relative to women. Moreover, we expected that relationships between perceived norms and drinking would be moderated by private SC, public SC, and social anxiety. As this relationship with social anxiety has been preliminarily investigated using only perceived descriptive norms (Neighbors et al., 2007a), we expected to extend the previous results by indicating a stronger relationship between perceived injunctive norms and drinking among more socially anxious students, particularly men.

Predictions for private SC and public SC were less clear. Due to the attributes associated with public SC such as elevated levels of awareness of the social self, we hypothesized that the relationship between perceived norms and drinking would be stronger for students higher in public SC, and particularly men. Finally, private SC has been shown to be linked with individuals who are less likely to conform to group pressure. Therefore we hypothesized that the relationship between perceived descriptive norms and drinking would be stronger for those who were lower in private SC. Conversely, the perception of others’ attitudes and permissiveness towards the use of alcohol (injunctive norms) may appear most accurate if/when it is in harmony with one’s actual attitudes. Thus, we predicted that the relationship between perceived injunctive norms and drinking would be stronger for those who were higher in private SC.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

A local Institutional Review Board approved the current study, which was part of a larger social norms intervention study designed to reduce alcohol consumption by correcting misperceptions of group-specific drinking behaviors. Participants for the study were recruited from fraternities, sororities, and service organizations at a midsize western university. Service organizations are groups of students who meet regularly and work together to perform service to the university and outside communities. Each group provided a membership list with members’ email addresses. In total, 1438 students from all 20 campus organizations (7 fraternities; 7 sororities; 6 service organizations) were invited to participate. Of those invitees, 1,168 participated in the data collection process, yielding a high rate of recruitment (81%). In total, 70% of participants were female, with 24% of participants from fraternities, 56% from sororities, and 20% from service organizations. The high percentage of females reflects the much higher proportion of female to male membership in these organizations. Age varied, with 13% 18 years old, 27% 19 years old, 31% 20 years old, 28% 21 years or older, and 1% “declined to state.” Nineteen percent were first-year students, 31% were sophomores, 29% were juniors, and 21% were seniors. Finally, the ethnic makeup of the sample was 66% Caucasian, 13% Hispanic, 7% mixed, 7% Asian/Pacific Islander, 3% African American, 3% “other,” and 1% “declined to state.”

2.2 Design and Procedure

Each member of each organization was invited to participate in an online Web-based survey during spring 2006. The survey took approximately 20 minutes to complete and all groups received nominal stipends (ranging from $125 – $250 depending on group size) for participation of their members. Participants were assured that all data were confidential and nothing about their individual or specific group responses would be communicated to any university personnel. All participants gave informed consent before completing the survey. The survey began with an assessment of demographic variables including age, sex, class year, group membership, and ethnicity.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Alcohol consumption

Before answering questions about drinking behavior, participants were presented with the definition of a standard drink (defined as a drink containing one-half ounce of ethyl alcohol — one 12 oz. beer, 8 oz. of malt liquor, one 4 oz. glass of wine, or one 1.25 oz. shot of 80 proof liquor). They were then given a self-report quantity and frequency index to assess alcohol use indicating how many days they drank alcohol in the previous month and the average number of drinks consumed on each drinking occasion. An “average standard drinks per month” variable was then computed for analyses by multiplying the frequency of drinking days by the average number of drinks per drinking occasion.

2.3.2 Self-consciousness

The 23-item Self-Consciousness Scale (Fenigstein et al., 1975) was used to measure SC. It is comprised of three distinct subscales assessing private SC (e.g. “I’m always trying to figure myself out”), public SC (e.g. “I’m concerned about what other people think of me”), and social anxiety (e.g. “It takes me time to overcome my shyness in new situations”. Participants’ responses were based on 5-point Likert scales ranging from 0 (extremely uncharacteristic) to 4 (extremely characteristic). Each subscale had adequate reliability: private SC (α = .71), public SC (α = .81), and social anxiety (α = .78).

2.3.3 Perceived norms

All questions assessing perceptions of normative group behavior utilized a sex and group specific reference group, directly referring to the name of the organization to which each member belonged. Participants responded to two questions about perceived injunctive norms. These items were taken from the House Acceptability Questionnaire (Larimer, 1992) and assessed a typical member’s perception of the group’s acceptability of two alcohol-related behaviors; “becoming intoxicated at a party,” and “missing a class because you are hung-over.” Response options ranged from: 1 = “Not Acceptable” to 7 = “Very Acceptable.” These two items have previously demonstrated adequate reliability with college students (Larimer, Cronce, Lee, & Kilmer, 2004) and revealed a significant correlation within our study for group perception (r = .36, p < .001).

Five modified CORE alcohol and drug survey questions (CORE, 2005) asked participants to estimate the drinking practices of a typical member of their group. These questions assessed perceived descriptive norms. Each question had response options ranging from one to nine. Again, these responses yielded perceived group norms. The first question assessed the frequency of drinking behavior (1 = “Never to 6 times a year” to 9 = “Everyday”). Question 2 assessed the quantity that was typically drunk during an average drinking occasion (1 = “None” to 9 = “13 or more drinks”). Question 3 assessed the quantity of drinks consumed per week (1 = “None” to 9 = “22 or more drinks”). Question 4 assessed the quantity of drinks drunk during the peak drinking occasion of the past 30 days (1 = “None” to 9 = “22 or more drinks”). Finally, question 5 assessed frequency of heavy episodic drinking asking how many times in the last two weeks a typical member of their group consumed four (female)/five (male) or more drinks in a two hour period (1 = “Never” to 9 = “10 or more times”). These five questions revealed adequate reliability (α = .88). For analyses, individual responses from the five descriptive norms questions (questions asking about “a typical member of your group”) were averaged together to form a perceived descriptive norm composite variable, while the two injunctive questions were averaged to form a perceived injunctive norms composite variable.

2.4 Analysis strategy

Inter-correlations among all primary study variables by gender are provided in Table 1. Hierarchical multiple regression (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003) was chosen as the primary analytic strategy with two regression analyses conducted. Separate analyses were conducted for perceived injunctive and descriptive norms to reduce the complexity of analyses and number of product terms and because previous research has found independent effects of descriptive and injunctive norms on college student drinking (e.g., Neighbors et al., 2007b). Moreover, recent research has suggested that injunctive norms may operate quite differently from descriptive norms even when they are relatively highly correlated with each other, with results depending more heavily on specification of the reference group in comparison to descriptive norms (Neighbors et al., in press). Thus in order to reduce the complexity of the analyses (i.e., number of regression terms) and because previous research has suggested the importance of considering descriptive norms and injunctive norms independently, we elected to analyze them in separate regression analyses. In subsequent analyses we examined the impact of controlling for injunctive norms in the descriptive norms analyses and controlling for descriptive norms in the analysis of injunctive norms. Results did not differ appreciably from those presented below. Importantly all statistically significant interactions remained significant.

Table 1.

Correlation matrix for study variables by gender. Note: Top half above the diagonal are correlations among females; bottom half below the diagonal are correlations among males.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Average standard drinks per month | - | .04 | −.02 | −.12** | .42** | .22** |

| 2. Public self-consciousness | −.15** | - | .59** | .34** | .02 | .06 |

| 3. Private self-consciousness | −.15** | .68** | - | .16** | .03 | .09* |

| 4. Social anxiety | −.06 | .28** | .12* | - | −.06 | −.03 |

| 5. Perceived descriptive norm | .60** | −.04 | −.15* | −.02 | - | .35** |

| 6. Perceived injunctive norm | .31** | .10 | .08 | −.01 | .48** | - |

Indicates a significant correlation at p < .01,

Indicates a significant correlation at p < .05

Gender was dummy coded (men = 1, women =0). All other predictors were mean centered to facilitate interpretation of interactions and to reduce multicollinearity. Twenty-five participants (2.1% of the sample) reported drinking in excess of 140 drinks per month. Following suggestions from Tabachnick and Fidell (2001), the drinking variable was windsorized to reduce the influence of outliers. Outliers were recoded to the highest value not considered to be an outlier. Scores of 140 drinks per month or higher represented 1.5% of the sample and were recoded to 139.43.

In the first analysis, average drinks per month (referred to henceforth as drinking) was specified as the dependent variable and main effects of gender, perceived descriptive norms, private SC, public SC and social anxiety were entered at step 1. Seven two-way product terms evaluating two-way interactions between gender, perceived descriptive norms, and each of the three SC variables were entered at step 2. Three product terms evaluating three-way interactions among gender, perceived descriptive norms and each of the SC variables were entered at step 3. The evaluation of interactions in hierarchical multiple regression analysis have been described in detail elsewhere (Cohen et al., 2003). Briefly, unlike traditional ANOVAs which include true and uncorrelated independent variables, in a regression framework, variables are typically correlated as are their product terms. It is customary to include predictor variables in a first analysis (i.e., Step 1), followed by two-way product terms which are tested in a subsequent model (Step 2) by adding relevant two-way product terms which control for each other as well as the main effects of the predictor variables. Similarly, three-way interactions are tested in a subsequent model (Step 3) by adding relevant three-way product terms to all of the terms included in Step 2. Statistical significance of predictors and interactions are evaluated in the model (or on the step) at which they are first entered and are typically not reported in subsequent steps in presenting the results. All predictors in a given model control for the influence of all other predictors in the same model and significance tests of regression coefficients are derived from Type III sums of squares.

Regression equations for each step of the analysis examining descriptive norms were as follows:

Step 1: y’drinking = Intercept + B1*gender +B2*perceived descriptive norms (DNORM) + B3*private SC (PVSC) + B4*public SC (PUSC) +B5*Social Anxiety (SA)

Step 2: y’drinking = Intercept + B1*gender +B2*DNORM + B3*PVSC + B4*PUSC +B5*SA + B6* Gender*DNORM + B7*Gender*PVSC +B8*Gender*PUSC + B9*Gender*SA + B10*DNORM*PVSC + B11*DNORM*PUSC + B12*DNORM*SA

Step 3: y’drinking = Intercept + B1*gender +B2*DNORM + B3*PVSC + B4*PUSC +B5*SA + B6* Gender*DNORM + B7*Gender*PVSC +B8*Gender*PUSC + B9*Gender*SA + B10*DNORM*PVSC + B11*DNORM*PUSC + B12*DNORM*SA + B13* Gender*DNORM*PVSC + B14* Gender*DNORM*PUSC + B15*Gender*DNORM*SA

In the second hierarchical analysis we followed the identical strategy replacing perceived descriptive norms with perceived injunctive norms. Effect size (d) was calculated using the formula (Rosenthal & Rosnow, 1991).

Significant interactions were interpreted following methods described in detail by Aiken and West (1991). Predicted cell means were graphed specifying high and low values as one standard deviation above and below their respective means. Tests of simple slopes were conducted to evaluate the statistical significance of slopes at high and low values of the relevant moderator.

3. Results

3.1 Regression using descriptive norms

Multiple regression results evaluating drinking as a function of gender, descriptive norms, private SC, public SC and social anxiety are in Table 2. Results at step 1 indicated that men and individuals higher in perceived descriptive norms reported significantly more drinking. Further, higher levels of social anxiety, and to a lesser extent, private SC (p = .07) were associated with less drinking. Public SC was not uniquely associated with drinking.

Table 2.

Regression results for “average standard drinks per month” as a function of sex, self consciousness, and perceived descriptive norms.

| Predictor | B | SE B | β | t | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: R2 = .36*** | |||||

| Gender | 11.24 | 2.00 | 0.15 | 5.63*** | 0.36 |

| Perceived Descriptive Norm (DNORM) | 13.14 | 0.71 | 0.51 | 18.52*** | 1.18 |

| Private Self-Consciousness (PVSC) | −0.38 | 0.21 | −0.06 | −1.79†** | 0.11 |

| Public Self-Consciousness (PUSC) | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.81*** | 0.05 |

| Social anxiety (SA) | −0.52 | 0.20 | −0.07 | −2.63*** | 0.17 |

| Step 2: R2 Δ = .02*** | |||||

| Gender X DNORM | 6.69 | 1.42 | 0.18 | 4.72*** | 0.30 |

| Gender X PVSC | 0.15 | 0.47 | 0.01 | 0.32*** | 0.02 |

| Gender X PUSC | −1.40 | 0.55 | −0.11 | −2.52*** | 0.16 |

| Gender X SA | 0.70 | 0.47 | 0.05 | 1.48*** | 0.09 |

| DNORM X PVSC | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.55*** | 0.03 |

| DNORM X PUSC | −0.01 | 0.20 | 0.00 | −0.05*** | 0.00 |

| DNORM X SA | −0.22 | 0.17 | −0.04 | −1.30 | 0.08 |

| Step 3: R2 Δ = .01** | |||||

| Gender X DNORM X PVSC | 0.09 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.25*** | 0.02 |

| Gender X DNORM X PUSC | −1.12 | 0.40 | −0.17 | −2.81*** | 0.18 |

| Gender X DNORM X SA | 0.50 | 0.35 | 0.06 | 1.42 | 0.09 |

Note.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Gender was dummy coded (Women = 0, Men = 1).

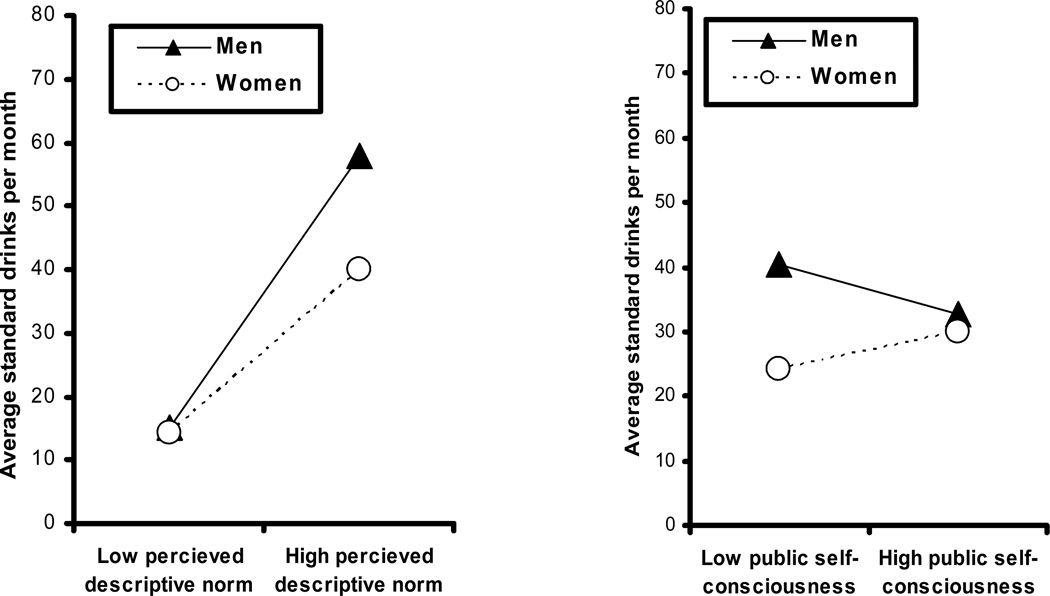

Results at step 2 indicated a significant interaction between gender and perceived descriptive norms and between gender and public SC. Figure 1 (left) presents the two-way interaction between gender and descriptive norms and reveals a stronger relationship between perceived descriptive norms and drinking among men relative to women. Tests of simple slopes indicated that while the relationship between perceived descriptive norms and drinking was stronger for men (β = .65, p < .001) than women (β = .39, p < .001) it was positive and significant for both. Figure 1 (right) presents the two-way interaction between gender and public SC. Tests of simple slopes suggested a significant positive relationship between public SC and drinking among women (β = .09, p < .05) and a trend for a negative relationship between public SC and drinking in men (β = −.11, p < .10).

Figure 1.

Two-way interactions involving gender—perceived descriptive norms (left) and public SC (right).

Results at step 3 indicated a significant three way interaction, qualifying both of the above described two-way interactions, among gender, perceived descriptive norms, and public SC. Figure 2 presents this three-way interaction and suggests that the stronger relationship between perceived descriptive norms and drinking for men relative to women was more pronounced among individuals who were lower in public SC. Moreover, tests of simple two-way interactions revealed a significant gender difference in the relationship between perceived descriptive norms and drinking among individuals who were lower in public SC (β = .31, p < .001) whereas this interaction was not significant among individuals who were higher in public SC (β = .02, p = ns).

Figure 2.

Three-way interaction among gender, perceived descriptive norms, and public SC

3.2 Regression using injunctive norms

Multiple regression results evaluating drinking as a function of gender, injunctive norms, private SC, public SC and social anxiety are in Table 3. Results at step 1 were consistent with previous regression analyses indicating more drinking among men than women and less drinking among individuals who were higher in private SC and social anxiety. In addition, individuals with more permissive perceived injunctive norms reported more drinking.

Table 3.

Regression results for “average standard drinks per month” as a function of sex, self-consciousness, and perceived injunctive norms.

| Predictor | B | SE B | β | t | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: R2 = .18*** | |||||

| Gender | 23.41 | 2.09 | 0.32 | 11.20*** | 0.71 |

| Perceived Injunctive Norm (INORM) | 6.14 | 0.77 | 0.23 | 8.02*** | 0.51 |

| Private Self-Consciousness (PVSC) | −0.65 | 0.24 | −0.10 | −2.78*** | 0.18 |

| Public Self-Consciousness (PUSC) | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.04 | 1.04*** | 0.07 |

| Social anxiety (SA) | −0.63 | 0.22 | −0.09 | −2.84** | 0.18 |

| Step 2: R2 Δ = .03*** | |||||

| Gender X INORM | 7.03 | 1.73 | 0.14 | 4.07*** | 0.26 |

| Gender X PVSC | −0.78 | 0.51 | −0.07 | −1.53*** | 0.10 |

| Gender X PUSC | −1.17 | 0.59 | −0.10 | −1.98*** | 0.13 |

| Gender X SA | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.04 | 1.11*** | 0.07 |

| INORM X PVSC | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.57*** | 0.04 |

| INORM X PUSC | −0.19 | 0.20 | −0.04 | −0.93*** | 0.06 |

| INORM X SA | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Step 3: R2 Δ = .02*** | |||||

| Gender X INORM X PVSC | 1.00 | 0.43 | 0.11 | 2.35*** | 0.15 |

| Gender X INORM X PUSC | −1.54 | 0.46 | −0.16 | −3.33*** | 0.21 |

| Gender X INORM X SA | 1.42 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 3.51*** | 0.22 |

Note.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Gender was dummy coded (Women = 0, Men = 1).

Results at step 2 were also consistent with results from the previous regression analyses and indicated a significant interaction between gender and perceived injunctive norms and between gender and public SC. Graphs of these interactions were comparable to those presented in Figure 1. Tests of simple slopes revealed, as with perceived descriptive norms, while the relationship between perceived injunctive norms and drinking was stronger for men (β = .42, p < .001) than women (β = .16, p < .001) it was positive and significant for both. With respect to the interaction between gender and public SC, tests of simple slopes again suggested a significant positive relationship between public SC and drinking among women (β = .09, p < .05) but the relationship between public SC and drinking among men was not significant (β = −.07, p = ns).

Unlike results for perceived descriptive norms, regression results at step 3 considering perceived injunctive norms indicated significant three way interactions among gender, perceived injunctive norms, and all three SC subscales. Figures 3, and 4 present interactions among gender, perceived injunctive norms, and private SC; and gender, perceived injunctive norms, and social anxiety, respectively. The graph of interaction between gender, perceived injunctive norms, and public SC looked similar to Figure 2 (gender X descriptive norms X public SC) and is therefore not included. Taken in turn, simple two-way interactions revealed that gender did not moderate the relationship between perceived injunctive norms and drinking among individuals who were lower in private SC (β = .04, p = ns) whereas, among those who were higher in private SC, the relationship between perceived injunctive norms and drinking was significantly stronger among men than women (β = .25, p < .001). In contrast, and consistent with results for perceived descriptive norms, among those who were lower in public SC, there was a significant gender difference in the relationship between perceived injunctive norms and drinking, being stronger for men (β = .29, p < .001). But among those who were higher in public SC, the relationship between perceived injunctive norms and drinking did not differ between men and women (β = .01, p = ns). Finally, with respect to social anxiety, among those who were less socially anxious, gender did not moderate the relationship between perceived injunctive norms and drinking (β = .02, p = ns) whereas among more socially anxious participants, the relationship between perceived injunctive norms and drinking was stronger for men than women (β = .27, p < .001).

Figure 3.

Three-way interaction among gender, perceived injunctive norms, and private SC

Figure 4.

Three-way interaction among gender, perceived injunctive norms, and social anxiety

3.3 Type of organization

While not of central interest to the research aims the data provided an opportunity to evaluate differences as a function of type of organization (Fraternity/Sorority vs. Service). Independent samples t-tests revealed that Greek students (Fraternity/Sorority) differed significantly from Service students. Specifically, Greek students were lower in private self-consciousness, t (1166) = −3.66, p < .001, d = −.21, and social anxiety, t (1166) = −2.05, p < .05, d = −.12, but drank considerably more, t (1164) = 8.57, p < .001, d = .50, and had higher descriptive norms t (1001) = 10.90, p < .001, d = .69, and injunctive norms, t (1003) = 2.23, p < .05, d = .14, compared with service students. We also examined whether inclusion of type of organization as a covariate in the regression analyses influenced the results. For the analysis of descriptive norms inclusion of type of organization did not meaningfully impact any of the results with the exception that the marginally significant association between private self-consciousness and drinking (p = .07) was no longer marginally significant (p = .15). All significant effects including interactions remained significant. Similarly, in the analysis for injunctive norms, results were unchanged with the exceptions that the previously significant association between private self-consciousness and drinking (p = .01) became marginally significant (p = .08) and the previously significant interaction between public self-consciousness and gender (p=.05) became marginally significant (p = .09) when including type of organization as a covariate. All other effects, including the three 3-way interactions remained statistically significant.

4. Discussion

The current study evaluated the relationship among gender, perceived norms, SC, and alcohol consumption in a sample of college students from various campus organizations. As expected, perceived norms and SC played significant roles with respect to drinking. There were direct effects of social anxiety and private SC on drinking, as each was associated with less alcohol consumption. Consistent with previous research, men and individuals with high perceived descriptive norms and those with more permissive perceived injunctive norms reported significantly more drinking. Two-way interactions revealed a moderation effect of gender on the relationship between perceived norms and drinking with the relationship between both perceived injunctive and descriptive norms and drinking stronger for men than women. Further and consistent with previous research (Neighbors et al., 2007a), social anxiety moderated the relationship between perceived norms (albeit only for injunctive norms) and drinking and this was primarily evident among men.

Given the lack of relevant previous literature, the findings related to private SC and public SC as moderators of relationships between perceived norms and drinking are more difficult to interpret. The stronger relationship between perceived descriptive norms and drinking for men relative to women was more pronounced among individuals who were lower in public SC, not higher in public SC as we had anticipated. Similarly, the hypothesis that the relationship between perceived descriptive norms and drinking would be stronger for those who were lower in private SC, was not supported. With respect to injunctive norms, results displayed significant three way interactions among gender, perceived injunctive norms, and all three SC subscales. Specifically, among those who were higher in private SC, the relationship between perceived injunctive norms and drinking was significantly stronger among men than women, as anticipated. In contrast, and consistent with results for perceived descriptive norms, among those who were lower in public SC, there was a significant gender difference in the relationship between perceived injunctive norms and drinking, again being stronger for men. It is worth noting that the two-way and three-way interactions with gender were evident despite the disproportionately female composition of the sample.

Overall, these findings suggest that the relationships between perceived norms and drinking vary differentially as a function of self-consciousness (SC subscales) and gender. First, perceived norms are more strongly associated with drinking for men than women. Previous research shows that students’ perceptions of heavy drinking men are more positive than perceptions of heavy drinking women (Prentice & Miller, 1993). Men appear to be more strongly reinforced in their perceptions and behavior regarding heavy drinking. Secondly, the current findings suggested that the gender differences in the relationships between perceived norms and drinking were more pronounced among lower levels of public SC and higher levels of private SC. These results are in some ways inconsistent with previous research suggesting that individuals higher in public SC are more susceptible to pressure to conform (Fenigstein, 1979; Froming & Carver, 1981; Scheier, 1980). One possible explanation is that public SC may be associated with responding to social desirability in self-report assessments of alcohol use. Thus, those who are lower in public SC may be more willing to report social influences on their drinking whereas those who are higher in public SC might be more reluctant to admit susceptibility to peer influences on their drinking. Alternatively, and more speculatively, public SC may to some extent reflect experience in social interactions involving drinking. Individuals who are lower in public SC may have different social networks and/or may be less likely to find themselves in social situations that involve drinking. Thus, when these individuals are in drinking situations, their drinking may model the behavior of those around them without explicit consideration of other’s approval or expectations. Moreover, perceived norms can be thought of as proxies for salient environmental drinking cues. It is possible that men who are lower in public SC, when in such environments, may drink more as a function of these cues without engaging in conscious reflection of how their behavior fits or doesn’t fit with the group. Consistent with this explanation are suggestions that the social context of fraternal organizations may overpower otherwise influential individual differences related to drinking (Larimer, Irvine, Kilmer, & Marlatt, 1997). Similar results were found in a study evaluating controlled orientation as a moderator of susceptibility to peer influences on drinking. Controlled orientation, which is conceptually related to public SC, was associated with greater susceptibility to peer influences on drinking, but only among non-fraternity men (Knee & Neighbors, 2002).

Alternatively, evidence suggests that the causal direction of the relationship between norms and drinking is reciprocal. Norms influence drinking but one’s own drinking also influences perceptions of others drinking (Neighbors, Dillard, Lewis, Bergstrom, & Neil, 2006). Thus, while perceived norms may influence behavior, it is also the case that at least sometimes perceptions of others’ drinking are a reflection of one’s own behavior. This may be particularly true among less publicly SC individuals, who rather than thinking consciously about how others drink, simply use their own behavior as a reference. Perceptions of other group members’ behavior and attitudes may not as strongly influence these individuals’ decisions to drink, as they are lower in public SC and not particularly interested in conforming to perceived standards of the group.

The later explanation might also be applicable with respect to private SC. The current study suggests that among those who were higher in private SC, the relationship between perceived injunctive norms and drinking was significantly stronger among men then women. Individuals higher in private SC hold a strong awareness of inner aspects of the self, such as private beliefs, attitudes, and values. As such, these individuals may also use their own behavior as a reference with regard to the formation of their perceived injunctive norms. Research indicates that these individuals are less susceptible to pressure to conform in groups (Froming & Carver, 1981; Scheier, 1980). They are more autonomous and independent in social settings and when faced with social demands (Buss, 1980; Fenigstein, 1987). Therefore higher endorsements of private SC are likely to reflect higher levels of perceived permissiveness towards drinking and lower levels of private SC are likely to reflect lower levels of perceived permissiveness towards drinking. This would serve to reinforce a more privately self-conscious individual’s attitudes by providing them with a seemingly more reliable internal frame of reference, as opposed to public SC, which seeks more external guides. One’s own values around alcohol would be understood as congruent with their perception of others, whereby reducing any cognitive dissonance that arises from a discrepancy in perceptions versus reality. Again, this result holds true for men, presumably because social influences appear to be stronger for male college students.

Finally, and consistent with expectations, the relationship between perceived injunctive norms and drinking was higher among students who are more socially anxious, and this interaction was also more true for men. To those individuals higher in social anxiety, personal and social faux pas may carry more subjective weight, leading to a greater susceptibility to peer influences. This finding builds upon previous research finding a three-way interaction of gender, social anxiety, and perceived drinking norms among first-year students (Neighbors et al., 2007a). The current study found this to be the case with perceived injunctive norms among members of social organizations and this lends support for the importance of behaviors and attitudes judged to be accepted in these groups.

4.1 Limitations

Limitations exist in the current study. Data that were used in analyses were collected retrospectively via self-report and are therefore susceptible to participant error in memory. However, studies and literature reviews suggest that self-report data is often valid and reliable among both adult and adolescent populations (Babor, Steinberg, Del Boca, & Anton, 2000; Brener, Billy, & Grady, 2003). Second, considering the important role that perceived injunctive norms play in the relationship with SC and drinking, future studies should look at how other injunctive norms might impact perceptions and drinking behavior. In addition, participants were all members of social organizations on campus. Research suggests that misperceptions of proximal reference groups are more likely to influence drinking behavior than misperceptions of distal reference groups (Borsari & Carey, 2003; Lewis & Neighbors, 2006). Additional research is needed with general campus populations to verify the relationships observed. Finally, the research is limited by the absence of additional group membership variables (e.g., length of group membership or group identity) that might help further explain or provide additional context to the present results.

4.2 Conclusion

The results of this study provide further implications for targeted interventions. Larimer, Turner, Mallett, and Geisner, (2004) call for targeted interventions with Greek organization members focusing on injunctive norms as well as descriptive norms. They found that correcting both misperceived descriptive and injunctive norms reduced heavy alcohol use within these organizations. The present findings suggest that men who perceive others in their group as permissive of alcohol-related behaviors and who report higher rates of private SC, social anxiety, and lower rates of public SC, drink more than other group members. This is promising for future research attempting to identify useful indicators of candidates who would most benefit from social norms interventions. If interventions and prevention efforts can be tailored to the most specific group possible (e.g. sex-specific) and based on characteristics that each member embodies (i.e., high private or low public SC), than perhaps those efforts will be more effective. Also, future norms based interventions should use SC as a potential moderator of intervention efficacy. Finally, more research is needed in the area of the bi-directional relationship between norms and drinking. Previously unidentified variables may also cause one’s own drinking to influence perceived norms. In sum, the present research extends previous findings regarding the relationships between SC and drinking and gender differences in the associations between social norms and drinking.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant from the Alcoholic Beverage Medical Research Foundation and Grant U18 AA015451-01 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Joseph W. LaBrie, Loyola Marymount University; Associate Professor; Director, Heads UP; Department of Psychology; 310-338-5238; jlabrie@lmu.edu; 1 LMU Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90045

Justin F. Hummer, Loyola Marymount University; Senior Research Associate, Heads UP; 310-338-7770; jhummer@lmu.edu; 1 LMU Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90045

Clayton Neighbors, University of Washington, Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 206-685-8704, claytonn@u.washington.edu, 4225 Roosevelt Way NE Box 354694 Seattle, WA 98105-6099

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Steinberg K, Del Boca F, Anton R. Talk is cheap: Measuring drinking outcomes in clinical trials. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:55–63. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz AD. The social norms approach: Theory, research, and annotated bibliography. 2004 (Available at http://www.edc.org/hec/socialnorms/theory.html). [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz AD, Perkins HW. Problem drinking among college students: A review of recent research. Journal of American College Health. 1986;35:21–28. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1986.9938960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A metaanalytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Billy JO, Grady WR. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: Evidence from the scientific literature. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:436–457. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH. Self-consciousness and social anxiety. San Francisco, CA: Freeman; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Antoni MH, Scheier MF. Self-consciousness and self-assessment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;48:117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen BA, Smith GT, Roehling PV, Goldman MS. Using alcohol expectancies to predict adolescent drinking behavior at one year. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:93–99. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Reno RR, Kallgren CA. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:1015–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Reasons for drinking among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-dimensional measure of drinking motives. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- CORE Institute. Southern Illinois University, Carbondale: Author; 2005. CORE Alcohol and Drug Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Fenigstein A. Self-consciousness, self-attention, and social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1979;37:75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Fenigstein A. On the nature of public and private self-consciousness. Journal of Personality. 1987;55:543–554. [Google Scholar]

- Fenigstein A, Scheier MF, Buss AH. Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1975;45:522–527. [Google Scholar]

- Froming WJ, Carver CS. Divergent influence of private and public self-consciousness in a compliance paradigm. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1981;15:159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Hope DA. College students and problematic drinking: A review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:719–755. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: Changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull JG. A self-awareness model of the causes and effects of alcohol consumption. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1981;90:586–600. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.90.6.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull JG, Young RD. The self-awareness reducing effects of alcohol consumption: Evidence and implication. In: Suls J, Greenwald AG, editors. Psychological perspectives on the self. Vol 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. pp. 159–190. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KA. Informal control networks and adolescent orientations toward alcohol use. Adolescents. 1986;21:767–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. On processes of peer influences in adolescent drug use: A developmental perspective. Advances in Alcohol & Substance Abuse. 1985;4:139–163. doi: 10.1300/J251v04n03_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knee CR, Neighbors C. Self-determination, perception of peer pressure, and drinking among college students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2002;32:522–543. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Seattle: University of Washington; 1992. Alcohol use and the Greek system: An exploration of fraternity and sorority drinking. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM, Lee CM, Kilmer JR. Brief intervention in college settings. Alcohol Research and Health. 2004;28:94–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Irvine DL, Kilmer JR, Marlatt GA. College drinking and the Greek system: Examining the role of perceived norms for high-risk behavior. Journal of College Student Development. 1997;38:587–598. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Mallett KA, Geisner IM. Predicting drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems among fraternity and sorority members: Examining the role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:203–212. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Social norms approaches using descriptive drinking norms education: A review of the research on personalized normative feedback. Journal of American College Health. 2006;54:213–218. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.4.213-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Dillard AJ, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL, Neil TA. Normative misperceptions and temporal precedence of perceived norms and drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:290–299. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Fossos N, Woods B, Fabiano P, Sledge M, Frost D. Social anxiety as a moderator of the relationship between perceived norms and drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007a;68:91–96. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007b;68:556–565. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, O’Connor RM, Lewis MA, Chawla N, Lee CM, Fossos N. The relative impact of descriptive and injunctive norms on college student drinking: The role of reference group. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/a0013043. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors, Walker, Larimer Expectancies and evaluations of alcohol’s effects among college students: Self-determination as a moderator. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:292–300. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park A, Sher KJ, Krull JL. Individual differences in the “greek effect” on risky drinking: The role of self-consciousness. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:85–90. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate texts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(Suppl 14):164–172. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW, editor. The social norms approach to preventing school and college age substance abuse: A handbook for educators, counselors, and clinicians. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW, Berkowitz AD. Perceiving the community norms of alcohol use among students: Some research implications for campus alcohol education programming. International Journal of the Addictions. 1986;21:961–976. doi: 10.3109/10826088609077249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW, Haines MP, Rice R. Misperceiving the college drinking norm and related problems: A nationwide study of exposure to prevention information, perceived norms and student alcohol misuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:470–478. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plüddemann A, Theron WH, Steel HR. The relationship between adolescent alcohol use and self-consciousness. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1999;44:10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice DA, Miller DT. Pluralistic ignorance and alcohol use on campus: Some consequences of misperceiving the social norm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:243–256. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, Rosnow RL. Essentials of Behavioral Research: Methods and Data Analysis. 2nd Ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Santee RT, Maslach C. To agree or not to agree: Personal dissent amid social pressure to conform. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1982;42:690–700. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF. Effects of public and private self-consciousness on the public expression of personal beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;39:514–521. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 4th Ed. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B, Castillo S. Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college: A national survey of students at 140 campuses. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;272:1672–1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Isaac N. 'Binge' drinkers at Massachusetts colleges: Prevalence, drinking style, time trends, and associated problems. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1992;267:2929–2931. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.21.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Lee H. College binge drinking in the 1990’s: A continuing problem: Results of the Harvard School of Public Health 1999 College Alcohol Study. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48:199–210. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee HP. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts: Findings from four Harvard School of Public Health study surveys 1993–2001. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Read JP, Palfai TP, Stevenson JF. Social influence processes and college student drinking: The mediational role of alcohol outcome expectations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:32–43. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]