Abstract

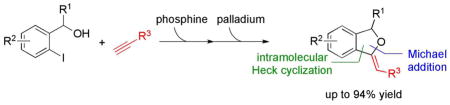

In this study we used sequential-catalysis—PPh3-catalyzed nucleophilic addition followed by Pd(0)-catalyzed Heck cyclization—to construct complex functionalized alkylidene phthalans rapidly, in high yields, and with good stereoselectivities (E:Z ratios of up to 1:22). The scope of this Michael–Heck reaction includes substrates bearing various substituents around the alkylidene phthalan backbone. Applying this efficient sequential-catalysis, we accomplished concise total syntheses of 3-deoxyisoochacinic acid, isoochracinic acid, and isoochracinol.

The rapid and efficient transformation of simple chemical building blocks into complex molecular structures remains one of the greatest challenges in synthetic organic chemistry. Traditional one-pot/one-transformation chemical processes are less than ideal for many reasons, including time, materials, and cost. Chemists are fascinated by tandem, cascade, and sequential-catalysis processes because they eliminate the need to isolate and purify intermediates.1 Accordingly, many groups have developed multi-catalyst systems that promote two or more chemical transformations in a single flask.2 These multi-step/single-flask operations minimize the time and cost of delivering complex molecular architectures from simple starting materials in a facile and efficient manner.

As part of a program aimed at advancing the scope of nucleophilic phosphine catalysis3 and realizing its potential for efficient multi-step/single-flask transformations, our group has developed a sequential-catalytic process, namely a tandem nucleophilic phosphine/palladium-catalyzed reaction sequence, for the construction of complex heterocycles from readily obtainable starting materials.

At present there are few routes available for the synthesis of highly functionalized phthalans, with most of them requiring reactions of elaborate disubstituted alkynes through iodocyclization,4 intramolecular Michael addition,5 or Wacker-type oxypalladation involving the use of palladium.6 One-pot transformations, while rare,7 are restricted in substrate scope and provide low yields and low stereoselectivity. Therefore, the challenge remains to develop concise one-pot procedures for the production of highly functionalized alkylidene phthalans with high efficiency and stereoselectivity.

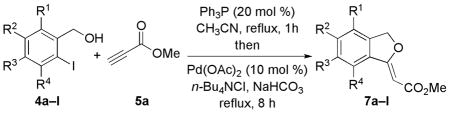

In this regard, we became interested in the tertiary phosphine–assisted nucleophilic Michael addition of alcohols onto activated acetylenes to give functionalized β-benzyloxy acrylates.8,9 With the goal of using these highly versatile β-benzyloxy acrylate intermediates for further generation of molecular complexity, we envisioned a subsequent cross-coupling event to take advantage of the compatibility of phosphines and palladium. Initially, in the presence of a phosphine, Michael addition of o-iodobenzyl alcohol to a propiolate generates a β-(o-iodobenzyloxy)acrylate. Then, employing the pre-existing phosphine as a ligand to promote the reduction of Pd(II) to Pd(0),10 the β-(o-iodobenzyloxy)acrylate undergoes intramolecular Heck cyclization.11 Joining these two transformations into a one-pot Michael–Heck procedure allows the synthesis of highly functionalized alkylidene phthalans.

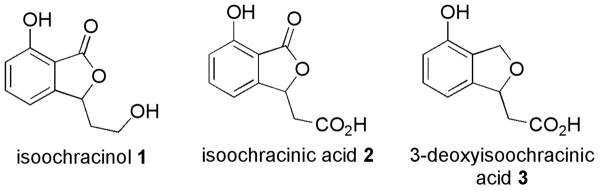

We suspected that a tandem Michael–Heck approach would offer rapid access to a group of rare fungal metabolites—isoochracinol (1), isoochracinic acid (2), and 3-deoxyisoochracinic acid (3)—from the genus Cladosporium.12 Among these compounds, 3-deoxyisoochracinic acid (3) exhibits antibacterial activity, inhibiting the growth of B. subtilis, a known cause of food poisoning (Figure 1).13

Figure 1.

Rare fungal metabolites

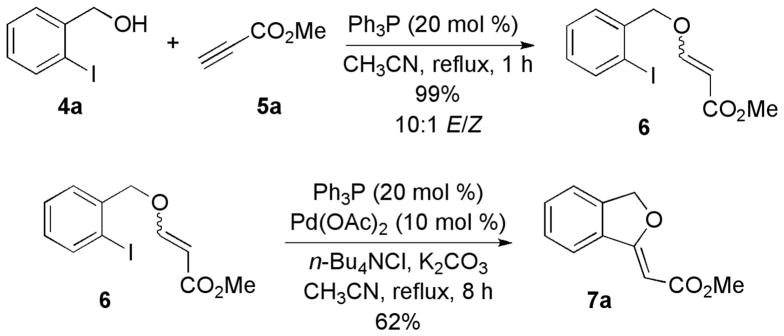

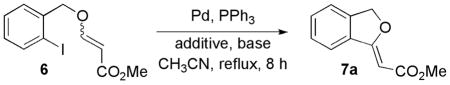

Before proceeding to the one-pot transformation, we investigated the efficiency of each reaction step. Slowly adding methyl propiolate into a solution of o-iodobenzyl alcohol and PPh3 in MeCN under reflux under Ar provided methyl β-(o-iodobenzyloxy)acrylate in 99% isolated yield after purification (Scheme 1). This Michael reaction produced a 10:1 mixture of E and Z isomers, which we separated and characterized unambigiously.14 We then subjected the mixture of β-(o-iodobenzyloxy)acrylates to Heck conditions, cleanly affording the target annulation product 7a, isolated as the major (Z) isomer.15

Scheme 1.

Stepwise Formation of an Alkylidene Phthalan

To incorporate this nucleophilic phosphine-catalyzed Michael addition into a sequential-catalysis process, we explored the possibility of executing the Pd(0)-catalyzed Heck cyclization without isolation of the β-(o-iodobenzyloxy)acrylate intermediate. First, using PPh3 to catalyze the Michael addition, we formed the desired Michael adduct rapidly. Next, were introduced Pd(OAc)2, tetrabutylammonium chloride (TBACl), and K2CO3 to the same flask. After 8 h, we isolated the major cyclic alkylidene phthalan 7a in 76% yield as the Z isomer, with complete consumption of the β-(o-iodobenzyloxy)acrylate intermediate 6 (Scheme 2). The one-pot procedure was operationally simpler and more efficient (76% yield) than the two-pot process (61%).

Scheme 2.

Preliminary Investigation of Sequential-Catalysis

Based on the yields of our two-pot synthesis, we targeted the Heck reaction to optimize the overall reaction efficiency (Scheme 1). The reaction rate decreased dramatically, providing only a trace of product, in the absence of TBACl (Table 1, entries 1 and 2), which is known to improve the yields of Heck reactions.16 From a screening of palladium catalysts, Pd(OAc)2 appeared to be the optimal Heck cyclization catalyst in the presence of PPh3, TBACl, and K2CO3 in MeCN under Ar (entry 6). To further improve the product yield, we screened several bases, with NaHCO3 emerging to give the highest efficiency, providing the Heck reaction product in 80% yield (entry 8). In the subsequent one-pot procedure, we obtained the phthalan 7a in 74% yield (Table 2, entry 1).

Table 1.

Optimization of Conditions for Heck Annulationa

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | palladium | additive | base | temp (°C) | yield (%)b |

| 1c | Pd(OAc)2 | – | Ag2CO3 | 66 | <5 |

| 2 | Pd(OAc)2 | – | Et3N | 82 | <5 |

| 3 | Pd(Ph3P)4 | nBu4NCl | K2CO3 | 82 | 0 |

| 4 | Pd2(dba)3 | nBu4NCl | K2CO3 | 82 | 0 |

| 5 | Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 | nBu4NCl | K2CO3 | 82 | 54 |

| 6 | Pd(OAc)2 | nBu4NCl | K2CO3 | 82 | 62 |

| 7 | Pd(OAc)2 | nBu4NCl | Ag2CO3 | 82 | 0 |

| 8 | Pd(OAc)2 | nBu4NCl | NaHCO3 | 82 | 80 |

| 9 | Pd(OAc)2 | nBu4NCl | Et3N | 82 | 74 |

| 10 | Pd(OAc)2 | nBu4NCl | PMPd | 82 | 59 |

Reaction conditions: 6 (0.5 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol %), PPh3 (20 mol %), nBu4NCl (0.5 mmol), base (1 mmol), CH3CN (10 mL), under Ar.

Isolated yield.

Reaction in THF.

1,2,2,6,6-Pentamethyl piperidine.

Table 2.

Reactions of 5a with Various o-Iodobenzyl Alcohols

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Nu | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | E:Za,b | yield (%)c |

| 1 | 4a | H | H | H | H | 1:3 | 7a, 74 |

| 2 | 4b | F | H | H | H | 1:4 | 7b, 70 |

| 3 | 4c | H | OBn | H | H | 1:3 | 7c, 65 |

| 4 | 4d | H | OMe | OBn | H | 1:4 | 7d, 52 |

| 5 | 4e | H | OMe | OMe | H | 1:3 | 7e, 72 |

| 6d | 4f | H | OTBS | H | H | 1:6 | 7f, 73 |

| 7 | 4g | H | CF3 | H | H | 1:3 | 7g, 60 |

| 8 | 4h | H | NO2 | H | H | 1:3 | 7h, 45 |

| 9 | 4i | H | Me | H | H | 1:4 | 7i, 71 |

| 10 | 4j | H | H | Me | H | 1:4 | 7j, 76 |

| 11 | 4k | H | H | H | Me | 1:16 | 7k, 94 |

| 12 | 4l | H | H | H | OMe | 1:22 | 7l, 91 |

Ratio determined from the 1H NMR spectrum of the crude product.

The E isomers were difficult to purify and characterize, due to the presence of other byproducts.

Isolated yield of the major (Z) phthalan.

The phthalan 7f was isolated as a phenol (i.e., without the protecting group).

These conditions were also viable for reactions of the alcohol component with various substituents on the benzene ring (Table 2). Accordingly, we isolated highly functionalized alkylidene phthalans as Z isomers in good to excellent yields. Both electron-donating and -withdrawing substituents were compatible with the optimized conditions, although reactions with strongly withdrawing trifluoromethyl and nitro functionalities provided lower yields of the desired alkylidene phthalans (entries 7 and 8). o-Iodobenzyl alcohols bearing substituents ortho to the iodine atom produced the corresponding alkylidene phthalans in excellent yields and high levels of stereoselectivity (entries 11 and 12).

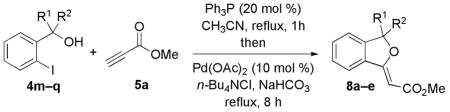

Next, we evaluated the effects of various substituents at the benzylic position of the pronucleophile 4 (Table 3). Monosubstituted pronucleophiles afforded the corresponding alkylidene phthalans in good yields (entries 1–4). Notably, the α-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl alcohol 4p underwent this sequential-catalysis smoothly (entry 4). The gem-dimethyl–substituted benzyl alcohol 4q did not provide its desired product, presumably because of the steric bulk of the tertiary alcohol nucleophile (entry 5).

Table 3.

Reactions of 5a with Various Benzylic Alcohols

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Nu | R1 | R2 | E:Za,b | yield (%)c |

| 1 | 4m | Me | H | 1:3 | 8a, 60 |

| 2 | 4n | Cyclopropyl | H | 1:3 | 8b, 72 |

| 3 | 4o | Ph | H | 1:5 | 8c, 60 |

| 4 | 4p | CF3 | H | 1:4 | 8d, 67 |

| 5 | 4q | Me | Me | — | 8e, 0 |

Ratio determined from the 1H NMR spectrum of the crude product.

The E isomers were difficult to purify and characterize, due to the presence of other byproducts.

Isolated yield of the major (Z) phthalan.

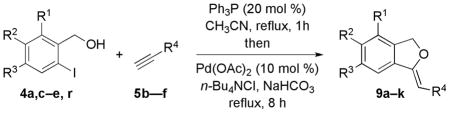

We also subjected an array of electron-deficient acetylenes to the optimized Michael–Heck reaction conditions (Table 4). In addition to benzyl propiolate (5b, entries 1–5), acetylenes with electron-withdrawing acyl and sulfonyl groups afforded their corresponding alkylidene phthalans in good yields (entries 6–10). The ethynyl phosphonate 5f was also a suitable substrate under the reaction conditions, albeit providing the phthalan 9k in low yield (entry 11).

Table 4.

Reactions with Various Electron-Deficient Acetylenes

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Nu | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | E:Za,b | yield (%)c |

| 1 | 4a | H | H | H | CO2Bn, 5b | 1:5 | 9a, 78 |

| 2 | 4c | H | OBn | H | CO2Bn, 5b | 1:3 | 9b, 51 |

| 3 | 4d | H | OMe | OBn | CO2Bn, 5b | 1:3 | 9c, 43 |

| 4 | 4e | H | OMe | OMe | CO2Bn, 5b | 1:4 | 9d, 67 |

| 5 | 4r | OBn | H | H | CO2Bn, 5b | 1:5 | 9e, 62 |

| 6 | 4a | H | H | H | COMe, 5c | 1:11 | 9f, 75 |

| 7 | 4c | H | OBn | H | COMe, 5c | 1:7 | 9g, 56 |

| 8 | 4e | H | OMe | OMe | COMe, 5c | 1:3 | 9h, 69 |

| 9 | 4a | H | H | H | COPh, 5d | 1:5 | 9i, 68 |

| 10 | 4a | H | H | H | Ts, 5e | 1:3 | 9j, 51 |

| 11 | 4a | H | H | H | PO(OPh)2, 5f | 1:5 | 9k, 16 |

Ratio determined from the 1H NMR spectrum of the crude product.

The E isomers were difficult to purify and characterize, due to the presence of other byproducts.

Isolated yield of the major (Z) phthalan.

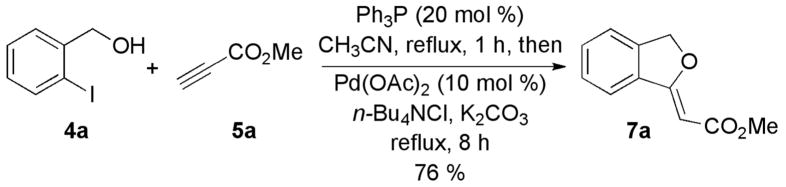

Scheme 3 presents a plausible mechanism for the Michael–Heck reaction, which commences with nucleophilic addition of PPh3 onto the electron-deficient acetylene 5a. The resulting phosphonium vinyl anion 10 deprotonates the pronucleophile 4a to provide the anion 11, which undergoes conjugate addition to another molecule of the acetylene 5a to give the intermediate 12,17,18 protonation of which gives the β-(o-iodobenzyloxy)acrylate 6. This final protonation step produces the alkoxide 11 and propagates the reaction. The Michael adduct 6 can also be generated through an addition/elimination pathway involving 11 and 13 via 14.

Scheme 3.

Proposed Reaction Mechanism

With the introduction of Pd(OAc)2, the pre-existing PPh3 becomes a ligand for Pd(II), reducing it to Pd(0). The active Pd(0) oxidatively inserts into the aryl iodide of the Michael adduct 6, generating the arylpalladium(II) complex 15, which undergoes carbopalladation in a 5-exo-trig manner to form 16. After rotation around the C–C single bond, 17 undergoes stereospecific syn β-hydride elimination to generate the alkylidene phthalan 7a and the palladium(II) halide 18, which, after reductive elimination of HI, regenerates the active Pd(0) species.

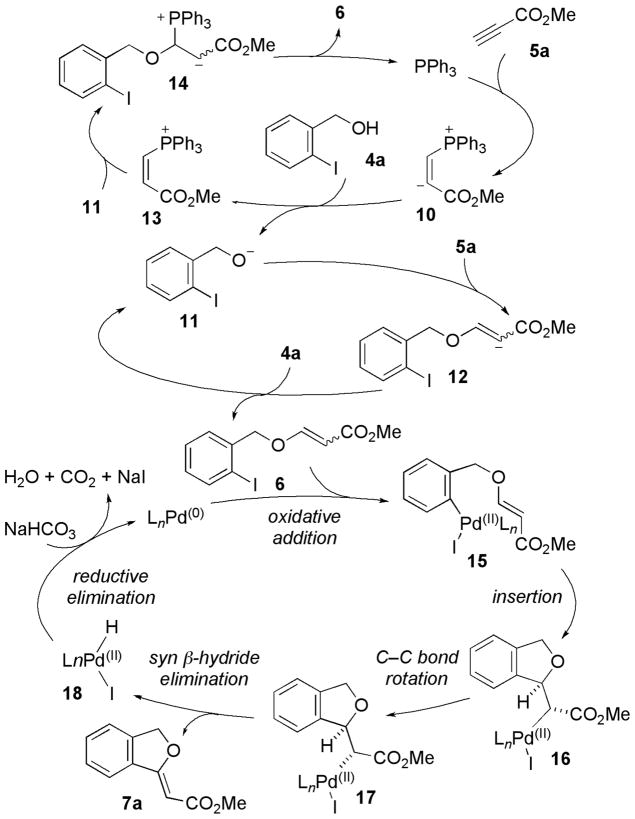

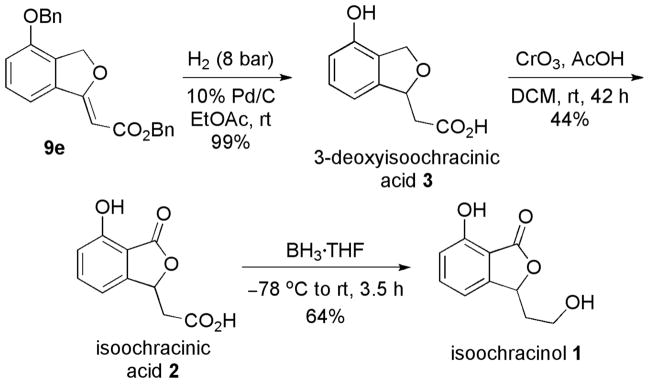

Applying the concept of Michael–Heck sequential-catalysis, we realized brief syntheses (Scheme 4) of isoochracinol (1), isoochracinic acid (2), and 3-deoxyisoochracinic acid (3).12,13 Starting from the alkylidene phthalan 9e, global debenzylation and hydrogenation of the olefin generated the natural fungal metabolite 3-deoxyisoochracinic acid (3) in quantitative yield. Furthermore, benzylic oxidation19 of 3-deoxyisoochracinic acid (3) with CrO3 and AcOH afforded isoochracinic acid (2). BH3·THF-mediated chemoselective reduction of the carboxylic acid moiety of isoochracinic acid (2) delivered isoochracinol (1).

Scheme 4.

Syntheses of the Natural Products 3-Deoxyisoochracinic Acid, Isoochracinic Acid, and Isoochracinol

In conclusion, we have developed Michael–Heck sequential-catalysis into an efficient and facile route toward highly functionalized (Z)-alkylidene phthalans from readily accessible o-iodobenzyl alcohols and electron-deficient acetylenes. The Michael–Heck technology provided the alkylidene phthalan intermediate 9e, which allowed rapid and efficient syntheses of the natural fungal metabolites isoochracinol (1), isoochracinic acid (2), and 3-deoxyisoochracinic acid (3). This method provides an economical (time, materials, cost) gateway to functionalized (Z)-alkylidene phthalans that are amenable to the synthesis of more-complex systems, including natural products.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the NIH (R01GM071779 and P41GM081282).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Characterization data; copies of 1H, 13C, and NOSEY NMR spectra for all compounds; representative experimental procedures. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Tietze LF, Brasche G, Gericke K. Domino Reactions in Organic Synthesis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.For selected recent reviews on multicatalytic concepts, see: Ajamian A, Gleason JL. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:3754. doi: 10.1002/anie.200301727.Lee JM, Na Y, Han H, Chang S. Chem Soc Rev. 2004;33:302. doi: 10.1039/b309033g.Wasilke JC, Obrey SJ, Baker RT, Bazan GC. Chem Rev. 2005;105:1001. doi: 10.1021/cr020018n.Enders D, Grondal C, Hüttl MRM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:1570. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603129.Chapman CJ, Frost CG. Synthesis. 2007:1.Walji AM, MacMillan DWC. Synlett. 2007:1477.

- 3.Reviews of phosphine catalysis: Lu X, Zhang C, Xu Z. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:535. doi: 10.1021/ar000253x.Valentine DH, Jr, Hillhouse JH. Synthesis. 2003:317.Methot JL, Roush WR. Adv Synth Catal. 2004;346:1035.Lu X, Du Y, Lu C. Pure Appl Chem. 2005;77:1985.Nair V, Menon RS, Sreekanth AR, Abhilash N, Biju AT. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39:520. doi: 10.1021/ar0502026.Ye LW, Zhou J, Tang Y. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:1140. doi: 10.1039/b717758e.Kwong CK-W, Fu MY, Lam CS-K, Toy PH. Synthesis. 2008:2307.Denmark SE, Beutner GL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:1560. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604943.Ye LW, Zhou J, Tang Y. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:1140. doi: 10.1039/b717758e.Aroyan CE, Dermenci A, Miller SJ. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:4069.Kumara Swamy KC, Bhuvan Kumar NN, Balaraman E, Pavan Kumar KVP. Chem Rev. 2009;109:2551. doi: 10.1021/cr800278z.Cowen BJ, Miller SJ. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:3102. doi: 10.1039/b816700c.Marinetti A, Voituriez A. Synlett. 2010:174.Kolesinska B. Cent Eur J Chem. 2010:1147.Wei Y, Shi M. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:1005. doi: 10.1021/ar900271g.Pinho e Melo TMVD. Monatsh Chem. 2011;142:681.Lalli C, Brioche J, Bernadat G, Masson G. Curr Org Chem. 2011;15:4108.Wang S-X, Han X, Zhong F, Wang Y, Lu Y. Synlett. 2011:2766.López F, Mascareñas JL. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:418. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002366.Zhao QY, Lian Z, Wei Y, Shi M. Chem Commun. 2012;48:1724. doi: 10.1039/c1cc15793k.Fan YC, Kwon O. Phosphine Catalysis. In: List B, editor. Science of Synthesis, Asymmetric Organocatalysis, Vol 1, Lewis Base and Acid Catalysts. Georg Thieme; Stuttgart: 2012. pp. 723–782.

- 4.Mancuso R, Mehta S, Gabriele B, Salerno G, Jenks WS, Larock RC. J Org Chem. 2010;75:897. doi: 10.1021/jo902333y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Mukhopadhyay R, Kundu NG. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:9475. [Google Scholar]; (b) Duan S, Cress K, Waynant K, Ramos-Miranda E, Herndon JW. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:2959. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Gabriele B, Salerno G, Fazio A, Pittelli R. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:6251. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bacchi A, Costa M, Cà ND, Fabbricatore M, Fazio A, Gabriele B, Nasi C, Salerno G. Eur J Org Chem. 2004:574. [Google Scholar]; (c) Peng P, Tang BX, Pi SF, Liang Y, Li JH. J Org Chem. 2009;74:3569. doi: 10.1021/jo900437p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Khan MW, Kundu NG. Synlett. 1999:456. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zanardi A, Mata JA, Peris E. Organometallics. 2009;28:4335. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Michael A. J Prakt Chem/Chem-Ztg. 1894;49:20. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bergmann ED, Ginsburg D, Pappo R. Org React. 1959;10:179. [Google Scholar]; (c) Jung ME. Comp Org Synth. 1991;4:1. [Google Scholar]; (d) Rele D, Trivedi GK. J Sci Ind Res. 1993;52:13. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inanaga J, Baba Y, Hanamoto T. Chem Lett. 1993;2:241. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dieck HA, Heck RF. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96:1133. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heck RF. J Am Chem Soc. 1968;90:5518. [Google Scholar]

- 12.These fungal metabolites exist as racemates in nature.

- 13.Höller U, Gloer JB, Wicklow DT. J Nat Prod. 2002;65:876. doi: 10.1021/np020097y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.We assigned the E and Z isomers based on the coupling constants of their vinyl protons. See the Supporting Information for detailed NMR studies, including 1H, 13C, and NOESY NMR spectra.

- 15.Subjecting the minor E-phthalan to the reaction conditions led to its isomerization to the favored Z form—the major product once the reaction reached equilibrium.

- 16.Jeffery T. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1984:1287. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grossman RB, Comesse S, Rasne RM, Hattori K, Delong MN. J Org Chem. 2003;68:871. doi: 10.1021/jo026425g. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Sriramurthy V, Barcan GA, Kwon O. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12928. doi: 10.1021/ja073754n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sriramurthy V, Kwon O. Org Lett. 2010;12:1084. doi: 10.1021/ol100078w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fan YC, Kwon O. Molecules. 2011;16:3802. doi: 10.3390/molecules16053802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrison IT, Harrison S. Chem Commun (London) 1966:752a. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.