Abstract

The well-documented higher rates of depression among sexual minority youth are increasingly viewed by developmentalists as a byproduct of the stigmatization of sexual minority status in American society and of the negative impact this stigma has on the processes associated with depression. This study attempted to spur future research by testing Hatzenbuehler’s (2009) psychological mediation framework to investigate the ways in which peer harassment related to sexuality puts young people at risk by influencing the cognitive, social, and regulatory factors associated with depression. Analyses of 15 year olds in the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development revealed that sexual minority status was largely associated with depressive outcomes via harassment, which was subsequently associated with depression via cognitive and social factors. Results point to various avenues for exploring the importance of the social world and self-concept for the outcomes of sexual minority adolescents in the future.

Keywords: sexual minority status, harassment, self-concept, depression

The past decade of research on mental health in sexual minority (i.e. gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender) youth has focused on the identification of the processes that account for the disparities seen between this group and the general population. Hatzenbuehler (2009) summarized two major theoretical perspectives that have been employed to address these disparities. First, the minority stress perspective calls for attention to social definitions of and responses to sexual minorities that increase the potential stress experienced in their everyday lives (Meyer, 2003). Much like theories of stigma in multiple disciplines (Goffman, 1963; Link & Phelan, 2001), this perspective argues that sexual minority status itself does not matter so much as the norms, values, mores, and related processes of the social contexts in which sexual minority individuals live. Indeed, higher rates of stressful experiences, anticipation of these stressful experiences, and the internalization of negative biases—the principal causes of minority stress—are well-documented links between sexual minority status and mental health in adolescence and adulthood (Almeida, Johnson, Corliss, Molnar, & Azrael, 2009; Bos, Sandfort, De Bruyn & Hakvoort, 2008; Loosier & Dittus, 2010; Meyer, 2003; Toomey, Ryan, Diaz, Card & Russell, 2010; Ueno, 2010). This framework, however, fails to identify how these processes are associated with the individual-level psychological factors responsible for the development of psychopathology (Hatzenbuehler, 2009).

Second, psychological process models emphasize the similarity in the etiology of mental health problems across different groups (Hatzenbuehler, 2009). This body of research highlights the cognitive, emotion regulation, and social factors that increase an individual’s risk of developing mental health problems, suggesting that these processes are highly similar in both sexual minority and non-sexual minority individuals (Diamond & Lucas, 2004; Saewyc, 2011). Although this framework helps to embed the study of sexual minority mental health within the larger context of developmental psychopathology, it does less to identify the sources of discrepancy found between sexual minority and sexual majority mental health that are repeatedly found in the etiological literature (Hatzenbuehler, 2009).

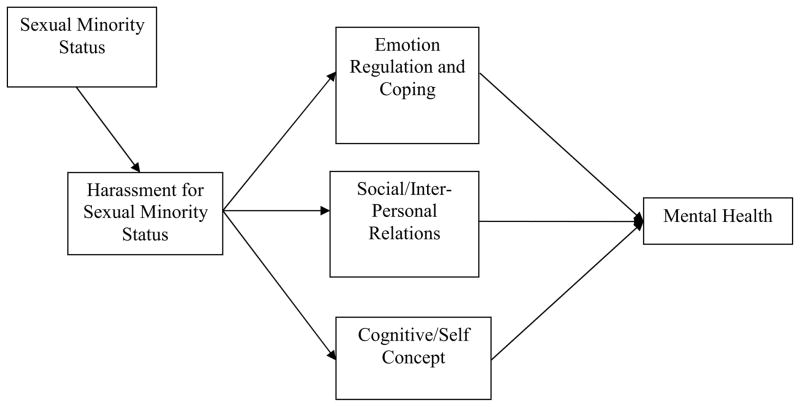

Hatzenbuehler (2009) combined these two theoretical approaches to develop the psychological mediation framework, in which increased exposure to distal stressors by sexual minority individuals negatively influences the cognitive, regulatory, and social mechanisms associated with the development of psychopathology, placing the individual at increased risk for negative mental health outcomes (see Figure 1). Our aim was to conduct an exploratory test of this model by examining depressive outcomes in sexual minority and sexual majority youth in a nationally-derived sample, focusing particularly on harassment perceived as occurring due to sexual minority status.

Figure 1.

Psychological Mediation Framework (adapted from Hatzenbuehler, 2009)

Harassment and its Socioemotional, Cognitive, and Regulatory Correlates

The psychological mediation framework suggests that certain experiences are more common in sexual minority populations that impact the social, regulatory, and cognitive factors subsequently associated with increases in the likelihood of depressive outcomes. Viewing peer harassment as a key factor in the psychosocial functioning of sexual minority youth is warranted and developmentally appropriate given the intense social dynamics of American secondary schools (Crosnoe, 2011). Indeed, evidence suggests that sexual minority youth face higher rates of name calling, threats, and interpersonal violence than non-sexual minority youth (Espelage, Aragon, Birkett & Koenig, 2008; Kosciw, Greytak, Diaz & Bartkiewicz, 2010; Toomey, McGuire & Russell, 2011) and documents the negative mental health outcomes associated with these kinds of harassment experiences (Birkett, Espelage & Koenig, 2009; Toomey et al., 2010; Williams, Williams, Pepler & Craig, 2005). Youth’s interpretation of harassment as stemming from sexual minority status may be linked with mental health problems over and above general harassment, as these perceptions feed and are fed by internalized homophobia constructs highlighted by the Minority Stress Model (Meyer, 2003). Of particular interest in light of psychological process models is that experiences of harassment due to sexual minority status are more common among, but not exclusive to, sexual minority adolescents, and that harassment relating to sexual minority status also has negative effects regardless of actual sexual minority status (Birkett et al., 2009; Poteat & Espelage, 2007; Reis & Saewyc, 1999).

The three types of mediators highlighted by the psychological mediation framework are social functioning, cognitive schemas, and emotion regulation. Starting with social and interpersonal factors, sexual minority youth report lower levels of social support (Needham & Austin, 2010; Williams et al., 2005), with support from both parents and peers having an important buffering function regarding negative outcomes (Espelage et al., 2008; Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995; Needham & Austin, 2010; Ryan, Russell, Huebner, Diaz & Sanchez, 2010; Sheets & Mohr, 2009; Williams et al., 2005). Much of the adolescent’s social environment is encapsulated by the school context (Crosnoe, 2011), and the school environment may be particularly important for sexual minority youth (Russell, 2002; Russell, Seif, & Truong, 2001). As such, adolescents’ perceptions of the school environment are an important facet of the social mechanisms influencing sexual minority outcomes. Previous research suggests that sexual minority youth have more negative perceptions of the school environment (Galliher, Rotosky & Hughes, 2004; Pearson, Muller & Wilkinson, 2007; Rostosky, Owens, Zimmerman & Riggle, 2003) and that these perceptions influence the association between sexual minority status and mental health (Birkett et al., 2009; Espelage, 2008; Pearson et al., 2007).

Hatzenbuehler’s model also highlights several cognitive mechanisms. Self-concept is a cognitive mechanism as it reflects the informational framework that individuals use to make sense of themselves (Berzonsky, 2004). Sexual minority youth may have more negative self-concepts than sexual majority youth (Galliher et al., 2004). Developing a coherent self-concept is a key task in adolescence (Evans, 1994; Marsh, Parada & Ayotte, 2004; Ward, Sylva, & Gresham, 2010), and may be particularly challenging for youth at elevated risk for peer victimization (Bellmore & Cillesen, 2006; Galliher et al., 2004), suggesting that self-concept can influence the mental health of youth experiencing elevated rates of victimization.

Finally, recent research suggests that the taxing of emotion regulation efforts by experiences of stigma may be a major mechanism by which experiences of prejudice lead to mental illness in minority populations (Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema & Dovidio, 2009). Sexual minority status in adolescence in particular has been linked to poorer emotion regulation and subsequent internalizing problems (Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008). Furthermore, victimization in general is also associated with regulatory difficulties (Rudolf, Troop-Gordon & Flynn, 2009; McLaughlin, Hatzenbuehler, & Hilt, 2009), suggesting that the individual level factors that increase the likelihood of victimization may increase the likelihood of emotion regulation difficulties as well.

Also of note are associations among social support, emotion regulation, and self-concept that support the simultaneous examination of these factors. For example, perceiving schools to be of higher socioemotional quality is associated with stronger self-concepts and better peer relations (Maddox & Prinz, 2003; Shochet, Homel, Cockshaw & Montgomery, 2008). The potential for overlap between these three concepts strongly suggests the possibility of shared variance in determining adolescent outcomes, supporting their simultaneous examination.

Depressive Symptoms among Sexual Minority Youth

Although the psychological mediation framework applies to multiple mental health outcomes, depressive outcomes are particularly relevant when studying adolescents. First, depression occurs at increasing rates across adolescence (Cole et al., 2002) and has a detrimental effect across multiple developmental outcomes including increased likelihood of poor mental health, lowered educational attainment, and lowered income in late adolescence and early adulthood (Dekker, Ferdinand, van Lang, Bongers, van der Ende & Verhulst, 2007; Fergusson, Boden & Horwood, 2007; Jonssson, Bohman, Hjern, von Knorring, Olsson & von Knorring, 2010). Second, a rich body of research links the social (e.g. peer relations, parental support, social skills), cognitive (e.g. self-worth, self concept), and regulatory (e.g. emotion identification, coping style) factors outlined in the psychological mediation framework to depressive outcomes in adolescence using prospective, longitudinal designs (Burwell & Shirk, 2006; Ciarrochi, Heaven, & Supavadeeprasit, 2008; McLaughlin et al., 2009; Montague, Enders, Dietz, Dixon & Cavendish, 2008; Needham, 2008; Prinstein & Aikins, 2004; Ward, Sylva, & Gresham, 2010). Third, elevated rates of depressive symptoms have been well documented among sexual minority adolescents (Galliher et al., 2004; Loosier & Dittus, 2010; Poteat, Aragon, Espelage & Koenig, 2009; Safren & Heimberg, 1999). Finally, previous research has suggested the important role of sexual minority stressors, such as harassment, in adolescent depression (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009; Toomey et al., 2010).

The Current Study

Social, self-concept, and regulatory factors play a key role in determining adolescents’ vulnerability to depressive symptoms, and they have been highlighted in the psychological mediation framework (Hatzenbuehler, 2009) as conduits in the association between prejudice and stigma and sexual minority mental health. As discussed above, the associations among cognitive, regulatory, and social factors and adolescent depression has been previously examined, yet this framework has not been fully tested through the simultaneous examination of these inter-related constructs. The current study offers the unique opportunity to test the mediating role of the inter-related cognitive, regulatory, and social factors in the association between sexual minority status and depressive outcomes with the goal of illuminating which of these factors plays the most important role in determining depressive outcomes in sexual minority youth.

The NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD) is uniquely suited for an exploratory examination of this model. A multi-state sample of youth who were 15 years of age during the most recent data collection, the SECCYD has a sufficient subsample of youth identifying as sexual minorities, provides multi-method data to capture the focal constructs, and allows for differences by gender, general harassment, family socioeconomic status, race, family structure, and maternal depression to be taken into account.

The first goal was to examine the unique role of harassment due to sexual minority status, by testing it as a mediator in the association between sexual minority status and cognitive, social, and regulatory factors. Sexual minority status was anticipated to be indirectly associated with these factors via harassment due to sexual minority status, such that harassment would be associated with poorer self-concept, less perceived support from parents, poorer friendship quality, lower perceived quality of the school environment, and poorer self-regulation. The second goal was to examine the association of these cognitive, social, and regulatory factors with youths’ self reported depression, controlling for a number of factors commonly associated with depression such as family income, maternal education, maternal depression, and depression from earlier in adolescence. Poorer sense of self-concept, less perceived support from parents, poorer friendship quality, lower school attachment, and poorer self-regulation were all expected to be associated with increased rates of depressive symptoms. The third goal was to examine the indirect associations between sexual minority factors and depression, testing whether the associations of both perceived harassment due to sexual minority status and sexual minority status itself with depression were completely accounted for by corresponding differences in the cognitive, social and regulatory factors.

Method

Participants

The SECCYD began in 1991 (for additional details see NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2005, and http://www.nichd.nih.gov/research/supported/seccyd.cfm) by recruiting parents of newborns from hospitals in 10 sites. The original sample included 1,364 families. Adolescents in the current study (n = 957, of whom 487 were girls) participated in data collection up through age 15, when they completed a self-report measure of depression (descriptive statistics available in Table 1). Data were drawn from assessments in multiple settings, including lab visits, home visits, and phone interviews.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for sexual minority and sexual majority adolescents

| Sexual Minority Adolescents | Sexual Majority Adolescents | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Mean | SD | Min | Max. | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | |

| Depression | 3.34* | 3.77 | 0.00 | 18.00 | 1.94 | 2.54 | 0.00 | 12.00 |

| Cognitive mediators | ||||||||

| Self-concept | 3.31* | 0.57 | 1.70 | 4.00 | 3.56 | 0.39 | 1.10 | 4.00 |

| Regulatory mediators | ||||||||

| Self-reported regulation | 11.55 | 3.66 | 3.00 | 20.00 | 12.13 | 3.09 | 2.00 | 20.00 |

| Maternal-reported regulation | 12.37* | 2.99 | 5.00 | 20.00 | 14.01 | 3.39 | 2.00 | 20.00 |

| Social interpersonal mediators | ||||||||

| Friendship quality | 4.25 | 0.50 | 2.25 | 4.96 | 4.16 | 0.56 | 2.21 | 5.00 |

| Maternal warmth and support | 27.83 | 5.63 | 14.00 | 36.00 | 28.95 | 5.41 | 9.00 | 36.00 |

| School environment factor | ||||||||

| School attachment | 3.22 | 0.61 | 1.60 | 4.00 | 3.30 | 0.57 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Negative school environment | 3.10 | 0.84 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 3.17 | 0.68 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Teacher bonding | 2.13* | 0.09 | 1.17 | 3.50 | 1.89 | 0.54 | 1.00 | 3.83 |

| Sociedemographic factors | ||||||||

| Family income (divided by 1,000) | 68.35* | 84.15 | 2.50 | 450.00 | 105.64 | 113.92 | 2.50 | 1,000.00 |

| Mother’s education | 13.45* | 2.58 | 7.00 | 21.00 | 14.51 | 2.43 | 7.00 | 21.00 |

| Maternal depression | 15.40* | 10.40 | 0.00 | 39.00 | 10.25 | 9.73 | 0.00 | 54.00 |

| Grade 6 depression | 2.24* | 3.08 | 0.00 | 14.00 | 2.05 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 19.00 |

| General victimization | 0.64 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 0.00 | 4.00 |

p < .01

Measures

Sexual minority status

Sexual orientation was established by a question asking if youths’ preferred romantic partners were girls, boys and girls, or boys.

Harassment due to sexual minority status

Youth were asked if, in the past year, they had been harassed because of their sexual orientation.

Depression

Depression was assessed in both grade 6 and at age 15 using the Short Form of the Child Depression inventory, comprised of the ten best discriminating and most consistent items from the Child Depression Inventory (Kovacs, 1992). This self-reported scale had an internal consistency of 0.80 (0.81 for sexual minority youth) and was significantly correlated with the long form version (r = 0.89), with higher scores being indicative of more depressive symptoms. The same scale was also used to assess the child’s self reported depression in grade 6, which was used as a control variable in the model (See Table 1 for descriptive statistics).

Self concept

Youth self concept was assessed using the Identity subscale of the Psychosocial Maturity Inventory (Greenberger, 1976) which includes questions addressing self-esteem and clarity of self. Other subscales from this measure were excluded as they were not theoretically relevant to the Psychological Mediation Model. The Identity subscale contains 10 items with higher scores reflecting better and more coherent self-concept (e.g., reversed scored I’m the sort of person who can’t do anything well, I never know what I’m going to do next), has a total Cronbach’s alpha of 0.77, an alpha of .84 for sexual minority youth, and was included as an observed variable in the current model.

Self-regulation

Self regulation was assessed using both primary caregiver (generally mother’s) and youths’ reported self control subscale from the Social Skills Rating System (Gresham & Elliot, 1990). This subscale includes 10 items, with higher scores indicating better regulation, and addresses the youth’s ability to self-regulate in emotionally challenging situations. The scale includes specific items addressing the youth’s ability to refuse unreasonable tasks politely, the youths’ ability to control their temper in conflict situations, and if the youth speaks in an appropriate tone of voice in the home (Maternal Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83, 0.87 for sexual minority adolescents; Adolescent Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74, 0.68 for sexual minority adolescents). These two scales were loaded onto a single factor for the current analyses.

Friendship quality

Friendship quality with the participant’s best friend was included as an observed variable as friendship is a major source of social support during adolescence. Adolescent perception of friendship quality with a best friend was assessed using a 29-item measure based on the Friendship Quality Questionnaire, with higher numbers of items reflecting higher friendship quality (Parker & Asher, 1993). Items addressed aspects of friendship including companionship and recreation, validation and caring, help and guidance, intimate disclosure, conflict and betrayal (reverse scored), and conflict resolution, and had a total Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 (0.85 for sexual minority youth).

Parental support

Youth described the warmth of their primary caregivers with 9 items that were summed into a single scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92; 0.90 for sexual minority youth) with higher scores reflecting greater maternal warmth. This scale assessed the youth’s perceptions of their primary caregiver’s caring and attentive behavior with questions such as “how often does your mother let you know she really cares about you” and “how often does your mother listen carefully to your point of view?” It was included as an observed variable due to the importance of parental warmth and support in determining adolescent mental health outcomes.

Quality of the school environment

Perceived socioemotional quality of the school environment was assessed with a latent factor that combined School Attachment (5 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.76), Teacher Bonding (3 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.61), and Negative Attitudes Towards School (6 items, Cronbach’s α = 0.69). These subscales had similar Cronbach’s alphas when restricted to sexual minority adolescents (School Attachment α = .72; Teacher Bonding α = .74; Negative Attitudes α = .61). These subscales were drawn from the What My School is Like Questionnaire, adapted from the New Hope Study (Duncan, Huston, & Weisner, 2007), with higher scores on School attachment and Teacher Bonding scales reflecting greater perceived quality of the school environment, and higher scores on the Negative Attitudes Towards Schools reflecting more negative associations. These subscales include items addressing children’s feelings about the safety, fairness, and quality of the school environment, and were included as a latent factor to assess the student’s perceptions of the school environment.

Control variables

Perceived victimization was assessed using the Peer Relationships Questionnaire, which was taken from the University of Illinois Aggression Scale (Espelage & Holt, 2001). General victimization was controlled to focus on the specific role of harassment due to sexual minority status, rather than more general experiences of victimization. This scale had four items (Cronbach’s α = 0.85, α = 0.92 for sexual minority youth) that asked the child to rate the number of times they were picked on, made fun of, called names and hit or pushed. A modest correlation was found between general victimization and harassment due to sexual orientation (r = .16, p < .01), suggesting that while related, the two represented separate constructs.

Socioeconomic status was measured using reports of maternal years of education and total family income (which was divided by 1,000 for the current analyses). Additionally, maternal depression was controlled for with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (Radloff, 1997). Participants were also asked about their race/ethnicity (81% white, 12% African American, 1% Asian or Pacific Islander, less than 1% Native American, 5% other). Finally, family structure was dichotomized according to father presence (63% of participants had their biological father present in the home).

Plan of Analyses

This basic model was tested with structural equation modeling (SEM) in Mplus 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010), as the data largely met normality assumptions. SEM establishes the fit between a proposed model and the actual covariance matrix, using a χ2 significance test, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), which is considered good at 0.06 or below, and a comparative fit index (CFI), which is considered good at 0.93 or above (Byrn, 1994; Stieger, 1990). SEM allows for the estimation of latent constructs (in this case school attachment and self-regulation). Mplus employs maximum likelihood (FIML), which uses existing correlations to estimate missing data, and allows for the assessment of both direct and indirect paths. Indirect pathways (e.g., between sexual minority status variables and depressive outcomes) are calculated using the Delta method. Finally, Mplus output can be used to calculate a measure of effect size for the association among variables. This effect size reflects the percentage of a standard deviation change occurring in the outcome as a result of a unit of increase in the predictor variable. This percentage was calculated by dividing the unstandardized coefficient for the predictor variable by the square root of the variance of the outcome variable.

Results

Initial descriptive findings suggested that four boys and six girls reported exclusive interest in same-sex partners, and seven boys and 23 girls reported romantic interest in both same and opposite sex partners. Youth reporting either same or both sex attraction were collapsed into a single sexual minority group. With regards to harassment due to sexual minority status, 34 youth reported being harassed once or twice, 8 reported being harassed more than twice, and the rest reported no harassment (i.e., 16 boys and 26 girls reported harassment). Youth were then dichotomized according to having experienced harassment due to their sexual orientation or not. Fourteen percent of youth who reported same-sex attraction experienced harassment due to their sexual orientation, while three percent of youth reporting only opposite-sex attraction reported harassment due to their sexual orientation. As such, overlap between orientation and harassment due to orientation did exist but was not absolute. Most likely, the sexual majority youth reporting this kind of harassment believed they were being harassed due to perceived sexual minority status. Another possible but unlikely explanation, however, would be that youth were harassed for being heterosexual.

In line with the first goal of the study, the first part of the model linked sexual minority status with harassment due to sexual minority status. As anticipated, the sexual minority status coefficient was significant and positive, such that sexual minority status was associated with 110% of a standard deviation increase in the likelihood of harassment. Table 2 presents results (standardized β coefficients) from the SEM capturing the paths in the conceptual model. The model fit the data well, as evidenced by the fit indices.

Table 2.

Standardized model results

| Intervening Variables | Outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Self-concept | Friendship | Parental Warmth | School Attachment | Self-regulation | Depression | |

| Sexual Minority Factors | ||||||

| Sexual minority status | −.10** | .06 | −.04 | .00 | −.11 | .02 |

| Harassment b/c sexual minority | −.10** | .07* | .01 | −.14** | −.12* | .04 |

| Psychosocial Factors | ||||||

| Self-concept | −.16** | .15** | .36** | .48** | −.33** | |

| Friendship quality | −.16** | −.19** | −.19** | −.24** | .07* | |

| Parental warmth and support | .15** | −.19** | .25** | .28** | .04 | |

| School attachment | .36** | −.19** | .25** | .71** | −.19** | |

| Self-regulation | .48** | −.24** | .28** | .71** | −.02 | |

| Control variables | ||||||

| Family Income | .08* | −.06 | .00 | .11** | .29** | −.01 |

| Maternal Education | .10** | −.02 | .05 | .20** | .36** | .13** |

| Gender (female) | −.03 | −.08* | .16** | .11** | .11t | .20** |

| Race (white) | .04 | −.02 | −.03 | .14** | .24** | .05 |

| Family structure (father present) | .12** | −.03 | .07* | .15** | .28** | .05t |

| Maternal depression | −.17** | .06* | −.02 | −.15** | −.30** | .05t |

| Victimization | −.34** | .23** | −.11** | −.26** | −.31** | .11** |

| Depression (grade 6) | −.34** | .13** | −.07* | −.19** | −.36** | .12** |

Model fit: χ2 = 182.62, df = 46, p < .001, RMSEA = .056, CFI = .94, SRMR = .03. R2 depression = .39. Note: Correlations among control variables were also estimated.

p < .05,

p < .01, t = p <.10.

The second part of the model linked harassment due to sexual minority status to self-concept, maternal warmth, friendship quality, school attachment, and regulation. Harassment due to sexual minority status was directly associated with poorer self-concept, lower self-regulation, and lower levels of school attachment by 50%, 60%, and 70% of a standard deviation, respectively. Unexpectedly, higher friendship quality was also associated with higher rates of harassment due to sexual minority status, such that 32% of a standard deviation increase in friendship quality was observed for adolescents reporting this kind of harassment. Harassment due to sexual orientation was not directly associated with lower reported parental warmth.

Direct and indirect associations between sexual minority status and self-concept, maternal warmth, friendship quality, school attachment, and regulation were also examined, although we had anticipated that these associations would occur via harassment due to sexual minority status. This was true for self-concept (β = −0.02, p < 0.01), school attachment (β = −0.03, p < 0.01), and self- regulation (β = −0.02, p < 0.05). Sexual minority status, however, was directly associated with 48% of a standard deviation decrease in self-concept.

In line with the second goal of this study, the third part of the model tested the associations between self-concept, maternal warmth, friendship quality, school attachment, and self-regulation and depressive outcomes. When examining these associations, maternal education, maternal depression, race/ethnicity, family structure, family income, depression from 6th grade, gender and general victimization were controlled. Negative perceptions of the school environment and less positive self-concept both predicted increases in depression by 37% and 80% of a standard deviation, respectively. Depression was also significantly predicted by a number of the control variables, including general victimization (see Table 2 for further details). Somewhat surprisingly, a positive association between friendship quality and depression was found in the current model (in which higher scores reflected better friendship quality), such that each standard deviation increase in reported friendship quality was associated with 12% of a standard deviation increase in depression.

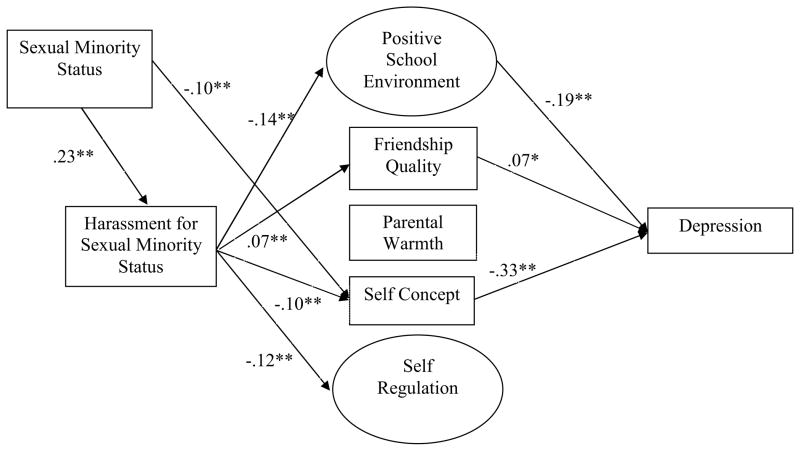

Finally, in line with the third goal, indirect, but not direct, paths between sexual minority status and depression and between harassment due to sexual minority status and depression were significant, as anticipated by the mediation framework. Specific indirect paths were found between harassment due to sexual minority status and depression via the school environment (β = 0.03, p < 0.01) and self-concept (β = 0.03, p < 0.01). Significant indirect effects were also found between sexual minority status and depression via self-concept (β = 0.03, p < 0.05), harassment and self-concept (β = 0.01, p <00.05), and harassment and the school environment (β = 0.01, p < 0.01). These findings suggest that sexual minority status was associated with depression via some of the mediators proposed by the psychological mediation framework.

To summarize, the psychological mediation framework was partially supported by the current data, such that sexual minority status was primarily associated with depression via harassment due to sexual minority status. Harassment due to sexual minority status was subsequently associated with depression via lowered sense of self-concept, and negative perceptions of the school environment (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Summary of the tested model (only significant pathways shown)

Discussion

This study focused on the small number of youth in an extant sample of typically developing children who reported same sex attraction and harassment believed to be due to their actual or perceived sexual orientation. The goal was to test the psychological mediation framework put forward by Hatzenbuehler (2009), such that multiple interrelated factors were tested simultaneously in relation to the associations among sexual minority status, harassment due to sexual minority status, and depression.

Perhaps most importantly, findings from this study suggest that the link between sexual minority status and depression occurred primarily via the greater likelihood of perceived harassment occurring due to sexual minority status, supporting the initial research hypothesis. Additionally, the direct and indirect effects of harassment on both the mediating variables and depression were larger for harassment that those for sexual minority status, supporting previous research emphasizing the importance of harassment in the mental health of sexual minority youth (Birkett et al., 2009; Toomey et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2005).

In particular, perceived harassment due to sexual minority status was significantly associated with lower levels of self-concept, more negative perceptions of the school environment, and poorer self-regulation. With regards to the second and third research goals, the school environment and self-concept were both determinants of depressive outcomes in the current sample, and it was via these factors that sexual minority status and harassment due to sexual minority status were associated with elevated rates of depression. The mediating role of the school environment suggests the importance of social factors in mental health during adolescence (Brown & Larson, 2009), supporting previous research identifying the school context as a central factor in adolescent wellbeing in general and among sexual minority youth in particular (Crosnoe, 2011; Russell, 2002; Russell, et al., 2001). The study of peer mechanisms within the school environment via network and other sociometric data is a potentially fruitful avenue of future research, (Crosnoe, 2011; Graham, Bellmore & Juvonen, 2003; Juvonen, Nishina & Graham, 2000).

The mediating role of self-concept reflects the importance of this construct in adolescent mental health (Auerbach, Abela, Ho, McWhinnie & Czajkowska, 2010; Chang, 2001; Evans, 1994; Sebastian, Burnett & Blakemore, 2008). Indeed, although this study included a measure of self-concept that reflected a number of inter-related self-concept constructs, this measure was extremely important in mediating between sexual minority status and depressive outcomes. Sexual minority status, however, was also directly associated with poorer self-concept. One of the limitations in using existent datasets to examine outcomes in sexual minority youth is that these datasets generally contain little information on constructs particular to sexual minority development (Horn, Kosciw & Russell, 2009). Although harassment due to sexual minority status is a major stressor experienced by sexual minority youth, the direct associations between sexual minority status and self-concept may reflect the fact that this was the only sexual-minority related stressor examined. And, although harassment is a particularly relevant stressor in adolescence, other stressors, including internalized stigma, may be important to sexual minority mental health (Frost, Parsons & Nanin, 2007; Radkowsky & Siegel, 1997; Saewyc, 2011).

Although several of the focal mediators supported the psychological mediation framework, others did not. Of particular note was the positive association between harassment due to sexual minority status and improved friendship quality as well as the subsequent association between higher friendship quality and higher reported depression. These findings may reflect the role of co-rumination, a process occurring within friendships in which the repeated and non-constructive discussion of problems is associated with increased risk of mood disorder (Rose, 2002; Stone, Hankin, Gibb & Abela, 2011). Indeed, co-rumination leads to both improved friendship quality as well as higher rates of internalizing problems, (Rose, Carlson & Waller, 2007), and rumination is associated with experiences of victimization (Barchia & Bussey, 2010). Friendship quality may also be higher for youth who experience persistent social stressors. Some previous research examining the mediating role of family support also indicates that sexual minority youth reporting higher levels of family support also reported higher levels of peer harassment, suggesting that these youth may use family support at a coping mechanism to deal with these negative experiences (Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995). The youth experiencing harassment in the current study may report closer friendships either as a protective response to their environment, or as a result of ruminative patterns within these close friendships.

The findings for self-regulation supported the first half of the model, in that poorer self-regulation was associated with sexual minority status via harassment due to sexual minority status, but not the second, as self-regulation was not subsequently associated with depression. These findings likely reflect the nature of the kind of regulation measured, which focused primarily on the down-regulation of aggressive behaviors. Indeed, previous research linking self-regulation with mental health outcomes in sexual minority and sexual majority populations has focused on negative regulatory constructs, such as rumination and suppression (Abela, Brozina & Haigh, 2002; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008), methods of regulation that are more closely associated with depressed affect (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1993), and are also disrupted by victimization experiences (Inzlicht et al., 2006). These findings add to the literature by suggesting that experiences of homophobia-related discrimination influence regulatory abilities associated with aggression, but future studies may wish to examine a variety of regulatory constructs in the examination of the psychological mediation framework.

The lack of information on sexual minority development may also explain the non-significant association between sexual minority variables and parental warmth and support (D’Augelli, Hershberger & Pilkington, 1998; Ryan et al., 2010; Needham & Austin, 2010). This divergence from past research may reflect that the association between maternal warmth and psychological functioning in sexual minority youth is not as strong when examined in the context of other factors, but it may also suggest methodological and developmental differences particular to the current study. Previous research has focused on youth who (1) were reporting support specifically for their sexual minority status, (2) had disclosed their sexual minority status to their parents, or (3) were older than the participants in the SECCYD (D’Augelli et al, 1998; Needham & Austin, 2010; Ryan et al., 2010). The participants in this study were 15 years of age, and did not provided information on their disclosure status. As the likelihood of disclosure of sexual minority status increases with age (Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000), any lack of association between sexual minority variables and parental factors may reflect that the youth in the current study had not disclosed their sexual minority status to their parents.

This study offered a unique opportunity to examine the psychological mediation framework. Several additional limitations, however, need to be addressed. Although we were able to control for previous history of depression, the majority of the data used in the current model was drawn from a single time period. The potential for a dynamic intertwining among different trajectories is central to many major developmental perspectives and needs to be thoroughly examined in the future (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998; Elder, 1998). This dynamic association may be particularly salient for the association between school attachment and victimization. Although victimization has been conceptualized as preceding school attachment (Wei & Williams, 2004), the social development model suggests that school attachment variables are associated with norms that subsequently reduce involvement in bullying behavior, which may ultimately alter the likelihood of victimization (Catalano, Haggerty, Oesterle, Fleming & Hawkins, 2004). Furthermore, some research with sexual minority youth suggests that it is the combination of self-acceptance and family support that is most strongly associated with positive mental health among sexual minority adolescents (Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995). In what areas of life are sexual minority youth—or youth harassed because of sexuality—at risk? Can risks in one domain filter into other domains over time, and can developmental competencies offer protection in other domains in which such youth are at risk?

Asking youth about the preferred gender of romantic partners assesses only one aspect of the complex behavioral, physical attraction, and identity components that are associated with sexual minority status (Saewyc, 2011; Savin-Williams & Ream, 2007; Sell, 2007). Furthermore, the ability to compare across gender was limited by sample size. The generalizability of these findings to larger samples using different assessments of sexual minority status may be limited, and future research using both identity or behavior based assessments of sexual minority status in larger samples may have different findings.

Most existing research, including this study, has a limited assessment of harassment (Almeida et al., 2009; Bos et al., 2008). Unpacking disparities in mental health due to sexual minority status may require a more thorough understanding of the nature of this harassment. Indeed, experiences such as witnessing victimization of others or exposure to negative stereotypes can influence mental health outcomes (Rivers, Poteat, Noret & Ashhurst, 2009), and were not measured here. Indeed, the current study focused on the role of perceived harassment due to sexual minority status, although general victimization was also included in the analyses, and was directly associated with depressive outcomes, reflecting previous work linking these variables (Nylund, Bellmore, Nishina & Graham, 2007; Pedersen, Vitaro, Barker & Borge, 2007; Troop-Gordon & Ladd, 2005). The distinction between harassment due to sexual minority status and more general victimization was made by the youth themselves, and may not accurately reflect the motivations of their victimizers. Harassment due to sexual minority status was modestly associated with general victimization, suggesting that the two are related but perhaps separate constructs. Future research may benefit by examining the factors associated with perceiving harassment as resulting from sexual minority status, and comparing the outcomes of these kinds of harassment experiences to more general victimization.

These findings serve as a point of departure from which to examine the psychological mediation framework. They support the importance of social context and self-concept in mediating between stressors such as harassment due to sexual minority status and mental health outcomes, such as depression. The SECCYD is a good starting point for such research, allowing us to sketch out basic ideas. Yet, it does not allow us to unpack processes involved in the mechanisms preliminarily explored here, and, of course, the sample contains only a small number of youth who identified as sexual minorities or reported experiencing harassment related to sexual minority status, making it difficult to compare across sexual minority subtype, gender, or ethnicity. This exploratory analysis, while based on a limited sample size, is telling regarding the role that self-concept and school environment factors play in determining depressive outcomes in sexual minority adolescents, with future data collection likely being necessary.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of a postdoctoral fellowship to the first author from Fonds Québécois de la Recherche sur la Société et la Culture, a faculty scholar award to the second author from the William T. Grant Foundation, and a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R24 HD42849, PI: Mark Hayward) to the Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin. Opinions reflect those of the authors and not necessarily those of the granting agencies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Almeida J, Johnson RM, Corliss HL, Molnar BE, Azrael D. Emotional distress among LGBT youth: The influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38(7):1001–1014. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9397-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach RP, Abela JRZ, Ho MR, McWhinnie CM, Czaikowska Z. A prospective examination of depressive symptomology: Understanding the relationship between negative events, self-esteem, and neuroticism. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29(4):438–461. [Google Scholar]

- Barchia K, Bussey K. The psychological impact of peer victimization: Exploring social-cognitive mediators of depression. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33(5):615–623. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellmore AD, Cillessen AHN. Reciprocal influences of victimization, perceived social preference, and self-concept in adolescence. Self and Identity. 2006;5(3):209–229. [Google Scholar]

- Berzonsky MD. Identity processing style, self-construction, and personal epistemic assumptions: A social-cognitive perspective. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2004;4:303–315. [Google Scholar]

- Birkett M, Espelage DL, Koenig B. LGB and questioning students in schools: The moderating effects of homophobic bullying and school climate on negative outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38(7):989–1000. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9389-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos HMW, Sandfort TGM, de Bruyn EH, Hakvoort EM. Same-sex attraction, social relationships, psychosocial functioning, and school performance in early adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(1):59–68. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Larson J. Peer relationships in adolescence. In: Steinberg L, editor. Handbook of adolescent psychology, vol 2: Contextual influences on adolescent development. 3. Hoboken, NJ US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2009. pp. 74–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. Ecology of developmental processes. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Volume 1: Theorectical models of human development. 5. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1998. pp. 993–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Burwell RA, Shirk SR. Self processes in adolescent depression: The role of self-worth contingencies. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16(3):479–490. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Haggerty KP, Oesterle S, Fleming CB, Hawkins JD. The importance of bonding to school for healthy development: Findings from the Social Development Research Group. Journal of School Health. 2004;74:252–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EC. Life stress and depressed mood among adolescents: Examining a cognitive–affective mediation model. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2001;20(3):416–429. [Google Scholar]

- Ciarrochi J, Heaven PCL, Supavadeeprasit S. The link between emotion identification skills and socio-emotional functioning in early adolescence: A 1-year longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescence. 2008;31(5):565–582. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Tram JM, Martin JM, Hoffman KB, Ruiz MD, Jacques FM, Maschman TL. Individual differences in the emergence of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: a longitudinal investigation of parents and child reports. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:156–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R. Fitting in, standing out: Navigating the social challenges of high school to get an education. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Hershberger SL, Pilkington NW. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families: Disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(3):361–371. doi: 10.1037/h0080345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker MC, Ferdinand RF, van Lang Natasja DJ, Bongers IL, van dE, Verhulst FC. Developmental trajectories of depressive symptoms from early childhood to late adolescence: Gender differences and adult outcome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48(7):657–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan G, Huston A, Weisner T. Higher Ground: New Hope for working families and their children. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH., Jr The life course as developmental theory. Child Development. 1998;69(1):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Aragon SR, Birkett M, Koenig BW. Homophobic teasing, psychological outcomes, and sexual orientation among high school students: What influence do parents and schools have? School Psychology Review. 2008;37(2):202–216. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Holt MK. Bullying and victimization during early adolescence: Peer influences and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2001;2(2–3):123–142. [Google Scholar]

- Evans DW. Self-complexity and it’s relation to development, symptomatology and self-perception during adolescence. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 1994;24(3):173–182. doi: 10.1007/BF02353194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Recurrence of major depression in adolescence and early adulthood, and later mental health, educational and economic outcomes. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;191(2):335–342. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Parsons JT, Nanín JE. Stigma, concealment and symptoms of depression as explanations for sexually transmitted infections among gay men. Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12(4):636–640. doi: 10.1177/1359105307078170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galliher RV, Rostosky SS, Hughes HK. School belonging, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms in adolescents: An examination of sex, sexual attraction status, and urbanicity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33(3):235–245. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Prentice-Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Bellmore A, Juvonen J. Peer victimization in middle school: When self- and peer views diverge. Journal of Applied School Psychology. 2003;19(2):117–137. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Bond L. Unpublished manuscript, Program in Social Ecology. University of California; Irvine: 1976. Technical manual for the Psychosocial Maturity Inventory. [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliot SN. The Social Skills Rating System. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Systems; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(5):707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49(12):1270–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J. How does stigma ‘get under the skin’?: The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science. 2009;20(10):1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger SL, D’Augelli AR. The impact of victimization on the mental health and suicidality of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Horn SS, Kosciw JG, Russell ST. Special issue introduction: New research on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: Studying lives in context. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38(7):863–866. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inzlicht M, McKay L, Aronson J. Stigma as ego depletion: how being the target of prejudice affects self-control. Psychological Science. 2006;17:262–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson U, Bohman H, Hjern A, von Knorring L, Olsson G, von Knorring A. Subsequent higher education after adolescent depression: A 15-year follow-up register study. European Psychiatry. 2010;25(7):396–401. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Nishina A, Graham S. Ethnic diversity and perceptions of safety in urban middle schools. Psychological Science. 2006;17(5):393–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) New York: Multi-health Systems, Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Diaz EM, Bartkiewicz MJ. The 2009 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. New York: GLSEN; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Loosier PS, Dittus PJ. Group differences in risk across three domains using an expanded measure of sexual orientation. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2010;31(5–6):261–272. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox SJ, Prinz RJ. School bonding in children and adolescents: Conceptualization, assessment, and associated variables. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6(1):31–49. doi: 10.1023/a:1022214022478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Parada RH, Ayotte V. A multidimensional perspective of relations between self-concept (self description questionnaire II) and adolescent mental health (youth self-report) Psychological Assessment. 2004;16(1):27–41. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hilt LM. Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking peer victimization to internalizing symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(5):894–904. doi: 10.1037/a0015760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague M, Enders C, Dietz S, Dixon J, Cavendish WM. A longitudinal study of depressive symptomology and self-concept in adolescents. The Journal of Special Education. 2008;42(2):67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Needham BL. Reciprocal relationships between symptoms of depression and parental support during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37(8):893–905. [Google Scholar]

- Needham BL, Austin EL. Sexual orientation, parental support, and health during the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39(10):1189–1198. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9533-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. Effects of rumination and distraction on naturally occurring depressed mood. Cognition and Emotion. 1993;7(6):561–570. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund K, Bellmore A, Nishina A, Graham S. Subtypes, severity, and structural stability of peer victimization: What does latent class analysis say? Child Development. 2007;78 (6):1706–1722. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Asher SR. Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson J, Muller C, Wilkinson L. Adolescent same-sex attraction and academic outcomes: The role of school attachment and engagement. Social Problems. 2007;54(4):523–542. doi: 10.1525/sp.2007.54.4.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson S, Vitaro F, Barker ED, Helman Borge AI. Early behavioral dispositions and middle childhood peer rejection and friendship: Direct, indirect and moderated links to adolescent adjustment. Child Development. 2007;78:1037–1051. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Aragon SR, Espelage DL, Koenig BW. Psychosocial concerns of sexual minority youth: Complexity and caution in group differences. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(1):196–201. doi: 10.1037/a0014158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Espelage DL. Predicting psychosocial consequences of homophobic victimization in middle school students. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2007;27(2):175–191. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Aikins JW. Cognitive moderators of the longitudinal association between peer rejection and adolescent depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology: An Official Publication of the International Society for Research in Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. 2004;32(2):147–158. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019767.55592.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radkowsky M, Siegel LJ. The gay adolescent: Stressors, adaptations, and psychosocial interventions. Clinical Psychology Review. 1997;17(2):191–216. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1997;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reis B, Saewyc E. Safe Schools Coalition of Washington. 1999. Eighty-three thousand youth: Selected findings of eight population-based studies. [Google Scholar]

- Rivers I, Poteat VP, Noret N, Ashurst N. Observing bullying at school: The mental health implications of witness status. School Psychology Quarterly. 2009;24(4):211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ. Co-rumination in the friendships of girls and boys. Child Development. 2002;73(6):1830–1843. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Carlson W, Waller EM. Prospective associations of co-rumination with friendship and emotional adjustment: Considering the socioemotional trade-offs of co-rumination. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43(4):1019–1031. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky SS, Owens GB, Zimmerman RS, Riggle ED. Associations among sexual attraction status, school belonging, and alcohol and marijuana use in rural high school students. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26:741–751. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Troop-Gordon W, Flynn M. Relational victimization predicts children’s social-cognitive and self-regulatory responses in a challenging peer context. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(5):1444–1454. doi: 10.1037/a0014858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST. Queer in America: Citizenship for sexual minority youth. Applied Developmental Science. 2002;6(4):258–263. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Seif H, Truong NL. School outcomes of sexual minority youth in the United States: Evidence from a national study. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24(1):111–127. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Russell ST, Huebner D, Diaz R, Sanchez J. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2010;23(4):205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc EM. Research on adolescent sexual orientation: Development, health disparities, stigma, and resilience. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21(1):256–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00727.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Heimberg RG. Depression, hopelessness, suicidality, and related factors in sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67(6):859–866. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams R, Diamond LM. Sexual identity trajectories among sexual-minority youths: Gender comparisons. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2000;29(6):607–627. doi: 10.1023/a:1002058505138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Ream GL. Prevalence and stability of sexual orientation components during adolescence and young adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2007;36:385–394. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian C, Burnett S, Blakemore S. Development of the self-concept during adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2008;12(11):441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell RL. Defining and measuring sexual orientation. In: Meyer IH, Northridge ME, editors. The Health of Sexual Minorities: Public Health Perspectives on Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Populations. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 355–374. [Google Scholar]

- Sheets RL, Jr, Mohr JJ. Perceived social support from friends and family and psychosocial functioning in bisexual young adult college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56(1):152–163. [Google Scholar]

- Shochet IM, Homel R, Cockshaw WD, Montgomery DT. How do school connectedness and attachment to parents interrelate in predicting adolescent depressive symptoms? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(3):676–681. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioural Research. 1990;25:173–180. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone LB, Hankin BL, Gibb BE, Abela JRZ. Co-rumination predicts the onset of depressive disorders during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0023384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, McGuire JK, Russell ST. Heteronormativity, school climates, and perceived safety for gender nonconforming peers. Journal of Adolescence. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz RM, Card NA, Russell ST. Gender-nonconforming lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: School victimization and young adult psychosocial adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46(6):1580–1589. doi: 10.1037/a0020705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troop-Gordon W, Ladd GW. Trajectories of peer victimization and perceptions of the self and schoolmates: Precursors to internalizing and externalizing problems. Child Development. 2005;76:1072–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno K. Same-sex experience and mental health during the transition between adolescence and young adulthood. The Sociological Quarterly. 2010;51(3):484–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2010.01179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward S, Sylva J, Gresham FM. School-based predictors of early adolescent depression. School Mental Health. 2010;2(3):125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Wei H, Williams JH. Relationship Between Peer Victimization and School Adjustment in Sixth-Grade Students: Investigating Mediation Effects. Violence and Victims. 2004;19:557–571. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.5.557.63683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams T, Connolly J, Pepler D, Craig W. Peer victimization, social support, and psychosocial adjustment of sexual minority adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2005;34(5):471–482. [Google Scholar]