Abstract

Objectives

Being one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality in developed countries, ischaemic heart disease's (IHD) incidence and mortality present clear differences between and within countries. Several authors already proposed possible explanations based on the demography, environmental factors, diet and level of urbanisation. This study reflects the Portuguese reality concerning IHD, by analysing the geographical distribution of hospital admissions and mortality due to this condition, in Portugal, and its association with demography, economical factors and the distribution of healthcare resources at the regional level.

Design

Ecological study.

Setting

Data from all Portuguese Public Hospitals were obtained using the National Registry of Hospital Admissions, between 2000 and 2007, and data on demography, economical factors and health resources distribution were obtained from the National Institute of Statistics.

Participants

Aggregated statistics on hospital admissions and mortality were computed for 278 counties based on almost 200 000 admissions.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Mortality rate; hospital admissions rate.

Results

The geographical distribution of non-adjusted mortality and hospital admission showed an inner/coastal pattern but no North/South gradient was clear. Counties with higher economical development had significantly higher mortality and admission rates. However, healthcare resources distribution was not significantly associated with IHD hospital admission and mortality. When adjusted for age, gender, economic development and health resources distribution, there was still unexplained geographical variation both in hospital admissions and mortality rates.

Conclusion

A pattern in the geographic distribution of incidence and mortality of IHD was clear even after the adjustment for age and gender. Economical variables were the ones presenting the strongest association. These types of analysis may be very helpful for the definition of health policies, in particular to identify priority regions for disease prevention and guidelines for healthcare resources distribution.

Article summary

Article focus

The geographic distribution of both hospital admissions and mortality rate due to IHD in Portugal.

The association of hospital admissions and death rate due to IHD and demography, economical factors and the distribution of healthcare resources at regional level.

Key messages

IHD was positively associated with economical power.

The distribution of healthcare resources presented no statistically significant association with both hospital admissions and mortality rate due to IHD.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Data used were originated from a national database containing hospital admissions to all Portuguese Public Hospitals between 2000 and 2007.

There is no recent information about geographical differences in diet in Portugal.

Introduction

In this article, we describe the Portuguese geographical pattern of ischaemic heart disease (IHD) incidence and mortality and exploit its association with demographic, economic power and distribution health resources distribution across regions. IHD is one of the leading causes of death in Europe but large variations on both mortality and incidence rates are observed between1 2 and within3–5 countries. For example, Muller-Nordhorn et al1 showed substantial differences in the standardised mortality rate (SMR) between countries in a recent report of cardiovascular mortality across European countries. France had the lowest rate of 65 deaths per 100 000 inhabitants and Latvia the highest one with 461 deaths per 100 000 inhabitants. In this list, Portugal appears with the second lowest SMR (87/100 000). Nevertheless, IHD remains as a leading cause of death and major cause of disability in Portugal.6 Additionally, cardiovascular diseases represent the main source of expense for the Portuguese National Health System according to OECD Health Data 20057 and, as a result, have been a concern for both clinicians and health policy authorities.

The variation of SMR across countries has been explained by heterogeneity in the geographical distribution of risk factors such as demography, diet, smoking, obesity, sedentary behaviour and environment8 but also differences in the economical development of the regions and distribution of medical care resources.9 10 These associations can be found at country level as well, and their report may provide valuable directions for research and public health measures.

This study reflects the Portuguese reality, but its methodology can be generalised to other applications. Moreover, in this study, we exploit a specific direction and we explore statistical associations between demographic factors, socioeconomic indicators, availability of health resources and geographical location and the incidence and mortality of IHD in Portugal, based on hospital admissions. From the perspective of socioeconomic differences, we use the Purchasing Power Index (PPI) of each county to characterise its economical power. From the perspective of the supply, we collected data referring to healthcare facilities, such as hospitals and human resources available in each county. Our main practical implication will be that having identified high- and low-risk regions, we will acknowledge at what extent demography, economical and health resources distribution are associated with incidence and mortality of IHD. A distinctive point of this paper is that we propose that income or income inequality, as in Massing et al,11 is important factors are associated with mortality rates. In fact, the more affluent societies are known to suffer from a higher incidence of certain diseases such as cardiovascular diseases. This is indicative of a different lifestyle, which is more prone to higher cardiovascular risk.

Overall, in other industrialised countries, previous studies have showed that there is significant variation of the incidence and mortality rate of IHD between and within European Countries. Portugal lacks a specific study of this problem, which is another of the innovative features of this paper. Additionally, several factors have been described as associated with these observed distributions of cardiovascular mortality.

Next, we explain our methodology and the database that we have used. It follows a discussion of the main findings and a presentation of the conclusions and some guidelines for future research.

Methods

Data sources

The national registry of Hospital Admissions includes information on all patients admitted to Portuguese Public Hospitals. We used all admissions, between 2000 and 2007, of adult patients (18 years or older) with main diagnosis of IHD (ICD-9 codes: 410–414). Patients discharged alive in <24 h were excluded given the improbability of having suffered any acute episode of IHD and thus presenting a high risk of misdiagnosis. The information retrieved included age, sex, patient's address, hospital admission, dates of admission and discharge and outcome at discharge (death or alive). It was not possible to identify multiple episodes of hospital admissions occurring for the same patient. Therefore, one patient may contribute multiple times for the number of events used in the calculation of the incidence rate.

The average number of hospital admissions per year and the number of hospital deaths were used as proxies of the national incidence and mortality rate for IHD.12 We computed the crude incidence and mortality rates by dividing the number of patients admitted for each county by the total population of the county above 18 years old. Patient's county was determined by his residency postal code. The term death rate is sometimes used in the results section to distinguish inhospital deaths among patients admitted with IHD.

Regional data on demography, economics and Healthcare resources distribution were obtained through the National Institute of Statistics (http://www.ine.pt). We used the size of population per county, together with age and sex, as the demographic characterisation of the counties. The county's population also provides some indication about the degree of urbanisation. The PPI was the economical variable used and served as a proxy of the Economical status of the population across the regions. The PPI indicates the purchasing power level of a region per inhabitant, in the comparison to the national average. It is a summary index of 17 economical variables that include, for example, income per capita, electric consumption, taxes and number of vehicles per capita, among others. It is represented as a base 100 index, meaning that if a region has a PPI of 110, it is 10% above the national average.

Regarding the healthcare resources, several indicators were obtained for each county: existence of a hospital in the county, existence of more than one primary care centre (all counties have at least one primary care centre), number of physicians per inhabitant, number of nurses per inhabitant, number of pharmacies and the average number of medical appointments per year and per inhabitant. The choice of these variables was driven by their availability at county level.

Finally, the geographic coordinates of each county were taken as the geometric centre of the county and were used to model the geographic variations of incidence and mortality.

Statistical analysis

Geographically, the Portuguese population is not uniformly distributed regarding age and sex. Therefore, we calculated the standardised admission ratio (SAR) and the SMR for each county using direct standardisation for sex and age group. The variables PPI, number of pharmacies, number of physicians, number of nurses and number of medical appointments were log transformed given the skewness of their distribution. For the same reason, the dependent variables SAR and SMR were also log transformed.

The association between demographic, economical and health resources variables with SAR and SMR was analysed using Pearson's correlations and simple linear regressions. The geographic distribution of both crude admission and mortality rates and SAR and SMR were modelled using a semiparametric regression for latitude and longitude. The predictive values of the semiparametric model were plotted in a heat-colour map of Portugal. Multivariable linear regression was then used to simultaneously adjust the association of the different covariates with SAR and SMR. The variables for the final model were selected in a stepwise fashion according to their statistical significance. Finally, the residuals of the linear model, representing the unexplained variation of SAR and SMR across the counties, were modelled using a semiparametric model for latitude and longitude. The fitted values of this model were again presented as a heat-colour map.

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS V.19.0 (Chicago, Illinois, USA) and R2.10.1 and the significance level was set at 0.05 for all the inferences.

Results

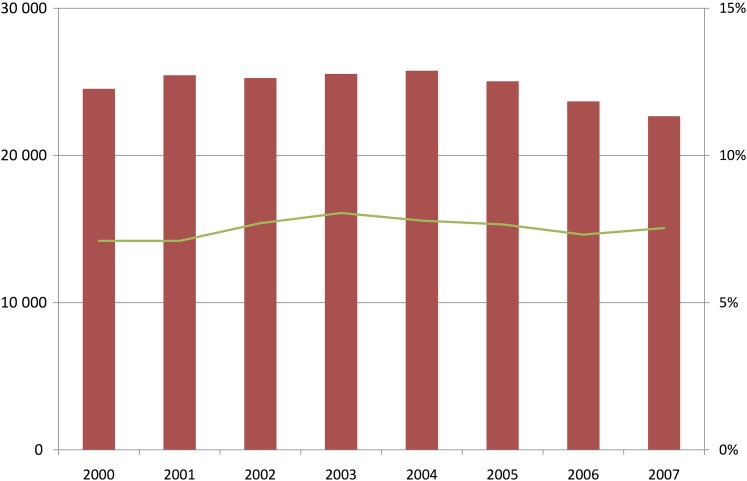

From 2000 to 2007, there were almost 200 000 admissions to 95 public hospitals in mainland Portugal, with IHD (ICD-9410-414) as main diagnosis, 65.4% of which were men. Seven and a half per cent of the admitted patients died (n=14 912). Death was significantly higher in women (10.5% vs 6.0% in men, p<0.001). Admitted patients had a mean (SD) age of 67 (12) years, a median (5th percentile, 95th percentile) length of inhospital stay of 6 (1, 21). In this period, the number of hospital admissions showed a slight decline, especially in the last years (24 527 admissions in 2000 vs 22 665 admissions in 2007). Death rate remained relatively constant over the years, around 7.5% (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Evolution of hospital admissions (bars) and fatality rate (line) of Ischemic Heart Disease in Portugal from 2000 to 2007.

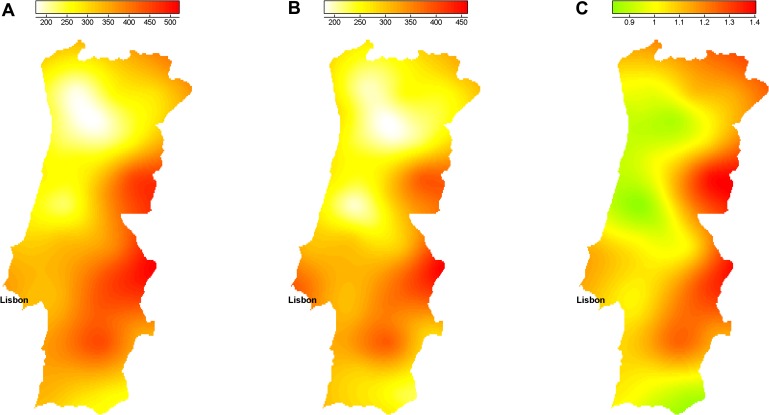

Admission and mortality rates were compared across the 278 counties. Admission rate presented a high geographic variability (figure 2A). A coast-interior pattern is clearly identified, especially in the centre region. Overall, the north coast region presented the lowest admission rate, while the centre-interior region presented the highest. The lowest admission rate was registered in Vizela (14.3 admissions per 100 000 inhabitants per year), a county located in the north interior. On the other hand, Covilhã, a county located in the centre-interior, registered the highest admission rate (701 admissions per 100 000 inhabitants per year).

Figure 2.

(A) Geographical distribution of the crude admission rate, (B) geographical distribution of the Standardized Admission Ratio and (C) geographical distribution of the residuals of the linear multiple regression. Legend refers to rates per 100 000 inhabitants.

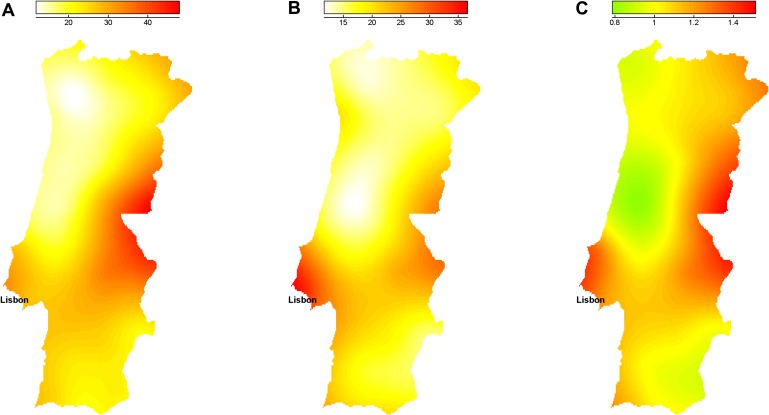

The county with lowest death rate was also Vizela (no deaths in 20 admissions), and the county with highest death rate is located in the north interior (Aguiar da Beira with 18.6% in 70 admissions). There was a high variability of the crude mortality rate across the country (figure 3A). The north half of the country presented a clear coast-interior pattern with the north coast showing the lowest mortality rate. Although not as clearly defined, the bottom half of the country suggests an opposite coast-interior pattern. The region around Lisbon, with the highest population density, also showed an elevated crude mortality rate.

Figure 3.

(A) Geographical distribution of the crude mortality rate, (B) geographical distribution of the Standardized Mortality Rate (SMR) and (C) geographical distribution of the residuals of the linear multiple regression. Legend refers to rates per 100 000 inhabitants.

After adjustment for age and gender, the patterns observed in the distribution of standardised admission rate (SAR) were in general similar to those observed with the crude rate. The patterns of SMR were generally intensified. However, the crude mortality rate in the interior regions tended to smooth out, when adjusted for age and gender. Also, the counties around Lisbon area were among the highest SMR in the country (eg, one of its counties, Loures, had the highest SMR—53 deaths per 100 000 inhabitants per year—in the country). Figures 2B and 3B show the geographical distribution of SAR and SMR, respectively.

Health resources distribution and socio-demographic indicators are presented in table 1. The PPI shows large differences across the counties with a minimum of 46 (in Vinhais) and a maximum of 236 (in Lisbon), indicating large disparities regarding the distribution of the economical power in mainland Portugal. The uneven distribution of population also points out the great differences found between regions; a pattern of coast-interior is clear with higher population density in the coast regions. Also, a north-south pattern may be identified, even though Lisbon has the highest population density, north regions tend to be more densely populated than south regions.

Table 1.

Distribution of health resources and social-economic indicators in the country

| Men, n (%) | 129 445 (65.4) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 67.4 (12.4) |

| Length of stay, median (P5, P95) | 6 (1, 21) |

| Population size, median (P5, P95) | 12 946 (3110, 122 174) |

| Purchasing Power Index, median (P5, P95) | 67.9 (49.2, 119.1) |

| Number of medical appointments (inhabit/year), median (P5, P95) | 3.2 (2.0, 4.8) |

| Number of nurses (1000 inhabit/county), median (P5, P95) | 2.0 (0.9, 9.4) |

| Number of physicians (1000 inhabit/county), median (P5, P95) | 1.1 (0.3, 4.6) |

| Number of pharmacies (1000 inhabit/county), median (P5, P95) | 0.3 (0.2, 0.8) |

| No hospital in the county, n (%) | 197 (70.9) |

| Only one primary healthcare centre in the county, n (%) | 250 (89.9) |

The distribution of health resources across the country was also markedly different. The country average number of physicians observed was 3.6/1000 inhabitants, ranging from 0 in two counties of the centre interior (Oleiros and Pampilhosa da Serra) to 23.6 in a county of the centre coast (Coimbra). Along with the physicians, the mean of nurses per 1000 inhabitants in Portugal was 5.0, ranging from 0.1 in three counties located in the interior of the country (Reguengos de Monsaraz, Sardoal e Vizela) to 24.7 also in Coimbra. Concerning pharmacies per 1000 inhabitants, 0.3 was the country mean, also ranging from 0.2 in several counties to 1.3. Seventy-one per cent (n=197) of the counties do not have a hospital (neither public nor private) and most of the counties (90%, n=250) have only one primary healthcare centre.

Table 2 presents the univariate associations between SAR and socio-demographic, economical and healthcare resource variables. Counties presenting a higher purchasing power, as well as more population, showed a significantly higher SAR (p<0.001 and p=0.010, respectively). Also, the existence of a hospital in the county as well as more than one primary healthcare centre and more pharmacies were associated with the higher SAR (p=0.017, p<0.001 and p=0.009, respectively). Counties with more physicians and more nurses presented a higher SAR (p<0.001). Finally, the number of medical appointments was the only covariate presenting a negative association with SAR (p=0.045).

Table 2.

Association between cardiovascular SAR and health resources availability (primary health centres, pharmacies, nurses, medical appointments, hospitals and physicians), economic factors (PPI) and demographic characteristics (population) across the 278 counties

| Univariate |

Multivariable |

||||

| r | B | p Value | B | p Value | |

| Purchasing Power Index | 0.441 | 1.255 | <0.001 | 1.476 | <0.001 |

| Population size | 0.153 | 0.117 | 0.010 | – | – |

| More than one primary health centre in the county | 0.230 | 0.270 | <0.001 | – | – |

| Existence of a hospital in the county | 0.144 | 0.112 | 0.017 | – | – |

| Number of pharmacies (1000 inhabitants/county) | 0.156 | 0.279 | 0.009 | 0.525 | <0.001 |

| Number of nurses (1000 inhabitants/county) | 0.220 | 0.254 | <0.001 | – | – |

| Number of medical appointments (inhabitants/county) | −0.120 | −0.392 | 0.045 | – | – |

| Number of physicians (1000 inhabitants/county) | 0.352 | 0.272 | <0.001 | – | – |

r, Pearson's correlation; B, linear regression coefficient; PPI, Purchasing Power Index; SAR, standardised admission ratio.

The association between the socio-demographic, economical and healthcare resources variables and SMR is described in table 3. Counties with higher PPI and more population had significantly higher SMR (p<0.001). Also, the number of physicians and nurses was positively associated with the SMR (p<0.001 and p=0.019, respectively). Having more than one primary healthcare centre was also associated with higher SMR (p<0.001). Similarly to the SAR, the number of medical appointments was the only negative association with SMR (p<0.001). The number of pharmacies and the existence of a hospital in the county were not significantly associated with SMR.

Table 3.

Association between cardiovascular SMR and health resources availability (primary health centres, pharmacies, nurses, medical appointments, hospitals and physicians), economic factors (PPI) and demographic characteristics (population) across the 278 counties

| Univariate |

Multivariable |

||||

| r | B | p Value | B | p Value | |

| Purchasing Power Index | 0.452 | 1.585 | <0.001 | 1.696 | <0.001 |

| Population size | 0.279 | 0.262 | <0.001 | – | – |

| More than one primary health centre in the county | 0.296 | 0.429 | <0.001 | 0.210 | 0.017 |

| Existence of a hospital in the county | 0.115 | 0.110 | 0.056 | −0.128 | 0.030 |

| Number of pharmacies (1000 inhabitants/county) | −0.001 | −0.002 | 0.988 | 0.286 | 0.020 |

| Number of nurses (1000 inhabitants/county) | 0.140 | 0.200 | 0.019 | – | – |

| Number of medical appointments (inhabitants/county) | −0.212 | −0.855 | <0.001 | – | – |

| Number of physicians (1000 inhabitants/county) | 0.307 | 0.292 | <0.001 | – | – |

r, Pearson's correlation; B, linear regression coefficient; PPI, Purchasing Power Index; SMR, standardised mortality rate.

Multivariable analysis

When adjusting the geographic distributions of socio-demographic characteristics and economical and health resources availability to each other, the results obtained were substantially different from those obtained in the univariate analysis. PPI and the number of pharmacies remained positively associated with the SAR (p<0.001 for both variables) when adjusting to the other covariates. The remaining variables were not significantly associated with the geographical distribution of SAR after adjustment for PPI and number of pharmacies. The adjusted r2 for the SAR is 0.27.

Concerning the analysis of SMR, counties with higher PPI and having more than one primary healthcare centre had a higher SMR (p<0.001 and p=0.017, respectively) after adjustment. The existence of a hospital in the county, which was not statistically significant in the univariate analysis, became negatively associated with SMR (p=0.020) indicating that counties with a hospital had lower SMR. Also, pharmacies became positively associated with SMR (p=0.030) when adjusting for the other covariates. The remaining variables (physicians, nurses, medical appointments and population size), which alone presented a significant association with SMR, were no longer significant after adjustment for PPI, more than one primary healthcare centre, existence of a hospital and number of pharmacies in the county. The adjusted r2 for the SMR is 0.24.

Unexplained variation of the SAR and SMR

Figures 2C and 3C present the geographic distribution of the unexplained variation of the SAR and SMR obtained through the regression residuals. Regions coloured in green indicate lower levels of hospital admissions and mortality than the one predicted by the model; regions coloured in yellow present a number of hospital admissions and mortality similar to those predicted by the multiple linear regression and regions coloured in red indicate areas where hospital admissions and mortality were higher than predicted by the respective models. There is a clear coast-interior pattern with the interior regions presenting higher SAR and SMR than the ones explained by socio-demographic, economical and health resources factors.

Discussion

We found a high variability, within the country, in the mortality and hospital admissions rates of patients with IHD. This heterogeneity was attenuated when the rates were adjusted for age and sex but large discrepancies can still be observed among the different counties. Economical differences and geographic distribution of health resources were associated with both mortality and admission rates but did not fully explain the regional variation of these rates. In any case, the PPI as a proxy of economical development and urbanisation of a region appeared as one of the strongest factors associated with both mortality and hospital admissions.

An exposure to city stress is the explanation provided by Christenfeld et al13 for the fact that both residents and visitors to NYC were 155% and 134% above the expected proportion (ie, the national average). However, they don't report actual measures of such stressed lifestyle. Also, an urban effect associated to IHD mortality has been proposed in several countries. For example, in Perisse et al14 and in McNutt et al,15 the suggested explanations for that phenomenon are lifestyle, socio-economic differences, eating habits and professional stress. A Norwegian study by Nafstad et al16 showed that urban air pollution might increase the risk of men dying, due to respiratory diseases, cancer or from IHD with an adjusted risk factor of 1.08%. Also, a Northern Irish study by O'Rilley et al17 suggested that urban areas tend to have higher mortality rates from all causes, mainly from respiratory diseases, IHDs and circulatory diseases, being air pollution the explanation pointed out to these findings. This is also a plausible explanation for the current findings, since there are more research findings of this sort, however none in the Portuguese case. A confirmation will depend on future work involving data regarding air pollution and others.

Another interesting finding was the positive association of mortality rate with the number pharmacies and primary healthcare centres, when adjusting for other factors, suggesting a higher mortality in counties with more pharmacies and more than one primary healthcare centre. A possible explanation for this association may be the residual confounding of an urban effect. In fact, counties with more pharmacies and more primary healthcare centres correspond to those with higher level of urbanisation, and the adjustment using the multivariable regression may not have fully eliminated this bias.

There was no association between the number of physicians or nurses and the mortality rates. These variables represent the supply side and the quantity of care. Although there are differences in the quantity of physicians and nurses across the hospitals, this was not validated as an explanation for the differences in mortality. This predicted effect was probably offset by other variables since there is a significant relationship if they are the single regressors of SMR.

There are important limitations in this study. We used hospital mortality of patients admitted with IHD as a proxy of the real IHD mortality rate. Also, we were not able to identify readmissions, so a patient may contribute more than one time to the incidence of IHD. However, these two errors are likely to be similar across all regions and therefore not affecting the comparability across counties.

Finally, given the nature of the ecological design, all the significant results found in the analysis are limited to statistical interpretation and no causality should be drawn from these associations. Even if we had data on all confounders, the adjustments that in the multivariable model would not remove the ecological bias, as explained by Greenland and Morgenstern.18

However, these results are useful to point new directions for research. Some interesting associations with SMR were observed, in particular, the economic dimension (here depicted by PPI), which are usually absent from the published literature and should be further investigated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the support given by the research project HR-QoD (quality of data (outliers, inconsistencies and errors) in hospital inpatient databases: methods and implications for data modelling, cleansing and analysis (project PTDC/SAU—ESA/75660/2006), sponsored by the Portuguese National Foundation of Science.)

Footnotes

To cite: Ferreira-Pinto LM, Rocha-Gonçalves F, Teixeira-Pinto A. An ecological study on the geographic patterns of ischaemic heart disease in Portugal and its association with demography, economic factors and health resources distribution. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000595. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000595

Contributors: LMF-P: literature review, statistical analysis and article writing. FR-G: interpretation of the results and article writing. AT-P: statistical analysis and article writing.

Funding: LMF-P was supported by Foundation of Science and Technology (Portugal), grant number BII/UNI/0753/SAU/2009.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There is no additional data available.

References

- 1.Muller-Nordhorn J, Binting S, Roll S, et al. An update on regional variation in cardiovascular mortality within Europe. Eur Heart J 2008;29:1316–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sans S, Kesteloot H, Kromhout D. The burden of cardiovascular diseases mortality in Europe. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology on cardiovascular mortality and morbidity statistics in Europe. Eur Heart J 1997;18:1231–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersohn F, Schlattmann P, Roll S, et al. Regional variation of mortality from ischemic heart disease in Germany from 1998 to 2007. Clin Res Cardiol 2010;99:511–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marrugat J, Elosua R, Aldasoro E, et al. Regional variability in population acute myocardial infarction cumulative incidence and mortality rates in Spain 1997 and 1998. Eur J Epidemiol 2004;19:831–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris RW, Whincup PH, Emberson JR, et al. North-south gradients in Britain for stroke and CHD: are they explained by the same factors? Stroke 2003;34:2604–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Portal Da Saude - Doenças Cardiovasculares. Portal Da Saude. Ministério Da Saúde, 1 Oct. 2009. 2012. http://www.min-saude.pt/portal/conteudos/enciclopedia da saude/doencas/doencas do aparelho circulatorio/doencascardiovasculares.htm [Google Scholar]

- 7.OECD OECD Health Update, July 2005. 2012. http://www.oecd.org/document/4/0,3746,en_2649_33929_35101892_1_1_1_1,00.html [Google Scholar]

- 8.Unal B, Critchley JA, Capewell S. Explaining the decline in coronary heart disease mortality in England and Wales between 1981 and 2000. Circulation 2004;109:1101–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avendano M, Kunst AE, Huisman M, et al. Socioeconomic status and ischaemic heart disease mortality in 10 western European populations during the 1990s. Heart 2006;92:461–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mensah GA. Ischaemic heart disease in Africa. Heart 2008;94:836–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Massing MW, Rosamond WD, Wing SB, et al. Income, income inequality, and cardiovascular disease mortality: relations among county populations of the United States, 1985 to 1994. South Med J 2004;97:475–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.May DS, Kittner SJ. Use of Medicare claims data to estimate national trends in stroke incidence, 1985-1991. Stroke 1994;25:2343–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christenfeld N, Glynn LM, Phillips DP, et al. Exposure to New York City as a risk factor for heart attack mortality. Psychosom Med 1999;61:740–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perisse G, Medronho Rde A, Escosteguy CC. Urban space and mortality from ischemic heart disease in the elderly in Rio de Janeiro. Arq Bras Cardiol 2010;94:463–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McNutt LA, Strogatz DS, Coles FB, et al. Is the high ischemic heart disease mortality rate in New York State just an urban effect? Public Health Rep 1994;109:567–70 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nafstad P, Haheim LL, Wisloff T, et al. Urban air pollution and mortality in a cohort of Norwegian men. Environ Health Perspect 2004;112:610–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Reilly G, O'Reilly D, Rosato M, et al. Urban and rural variations in morbidity and mortality in Northern Ireland. BMC Public Health 2007;7:123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenland S, Morgenstern H. Ecological bias, confounding, and effect modification. Int J Epidemiol 1989;18:269–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.