Abstract

Introduction

Acute pain is a hallmark of sickle cell disease (SCD) for which frequent hospital admissions may be required, affecting the quality of life of patients.

Objectives

To characterise the relationship between adult patient self-reported sickle cell pain, mood and quality of life during and after hospital admissions.

Design

Longitudinal study across three time-points.

Setting

Secondary care, single specialist sickle cell centre.

Participants

510 adult patients with SCD admitted to hospital daycare or inpatient units.

Outcome measures

Self-assessments of pain, mood and health-related quality of life with health utility (measured on the EQ-5D) on admission, before discharge and at 1-week postdischarge.

Results

Mood, general health and quality of life showed significant steady improvements with reduction of pain in patients with SCD on admission to hospital, before discharge and at 1-week follow-up (p<0.01). Health utility scores derived from the EQ-5D showed a negative association with pain in regression analysis over the three time-points.

Conclusion

Examining health-related quality of life and health utility in relation to pain during hospital admissions is valuable in terms of targeting appropriate psychological interventions within the context of a multidisciplinary approach to managing sickle cell pain. This has implications for healthcare costs.

Article summary

Article focus

Acute pain is a hallmark of SCD for which hospital admissions may be required.

This study explores the relationship between patient self-assessments of pain, mood and health-related quality of life with health utility (measured on the EQ-5D) during and after hospital admissions.

Key messages

Mood, general health and quality of life steadily improve with reduction of pain during and after an acute sickle cell pain episode.

A multidimensional approach to assessing sickle cell pain in hospital is useful. This helps to identify comorbidities such as mood changes that may affect length of stay with healthcare cost implications.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Health utility indices for an in-patient sickle cell pain population are reported for the first time. Quality of life and emotional changes are also highlighted.

Nonetheless, this is based on information from one setting and may be different from others.

Introduction

Pain associated with vaso-occlusion in sickle cell disease (SCD) is a life-long persistent and significant problem, which has profound medical, psychological and social implications for affected patients and their families. Recurrent acute pain episodes in SCD are variable for which frequent hospitalisations may be required.1 2 More than 90% of hospital admissions of patients with SCD in the UK have been shown to be for acute pain treatment,3 and the management of acute painful episodes continues to pose a challenge for haematologists.

Sickle cell pain assessment is a crucial and difficult task. Accurate estimation of this pain is important in its control and management. Inadequate treatment for sickle cell pain continues to be an important problem, and a major issue is the restricted assessment methods utilised. First, similar to other types of pain, there is no medical assessment or physiological measure of sickle cell pain that is objective. Pain assessment and treatment in patients with SCD have historically been based on the opinion of clinical staff within a particular medical setting. This may have led to discrepancies between their ratings of pain severity or the amount of pain relief required and that of patients, as highlighted in an earlier study.4 Second, pain experiences in SCD are multidimensional, and quite importantly in sickle cell pain, other dimensions including emotional stress, mood, activity levels and general health factors have to be considered.5 Moreover, inadequate pain management seems to greatly reduce quality of life in all types of patients with pain and across all ages, with consequences such as anxiety, fear and sleep disturbance.6 Appropriate pain care models have been shown to improve quality of life in SCD.7 In order to address these issues and their clinical implications with respect to the assessment and treatment of sickle cell pain within a hospital setting, a multidimensional assessment tool was developed.

Patients with sickle cell pain who are admitted to Central Middlesex Hospital in London are treated with morphine (or alternative opioid) via a patient-controlled analgesia pump as standard. The multidisciplinary approach to the clinical management of sickle cell pain includes routine psychological assessments, which have been incorporated into the inpatient protocols and allow for appropriate interventions. These patient self-complete assessments were referred to as the ‘Sickle Cell Patient Self Assessment of Own Health State’ (figure 1), which are administered on admission, before discharge and at 1 week after discharge (by telephone call from a psychologist). This assessment tool is mainly a combination of health-related quality of life (HRQoL)/health utility obtained from the EuroQol EQ-5D8 and pain status measures. The EQ-5D is a standardised instrument for use as a measure of health outcome and health utility, which provides a simple descriptive profile and a single index value for health status. Pain status includes assessments of pain intensity and pain relief; there is also a mood score. The present study is based on a retrospective audit review of standard psychological assessments in adults with sickle cell pain admitted to Central Middlesex Hospital over a 5-year period until the end of 2010.

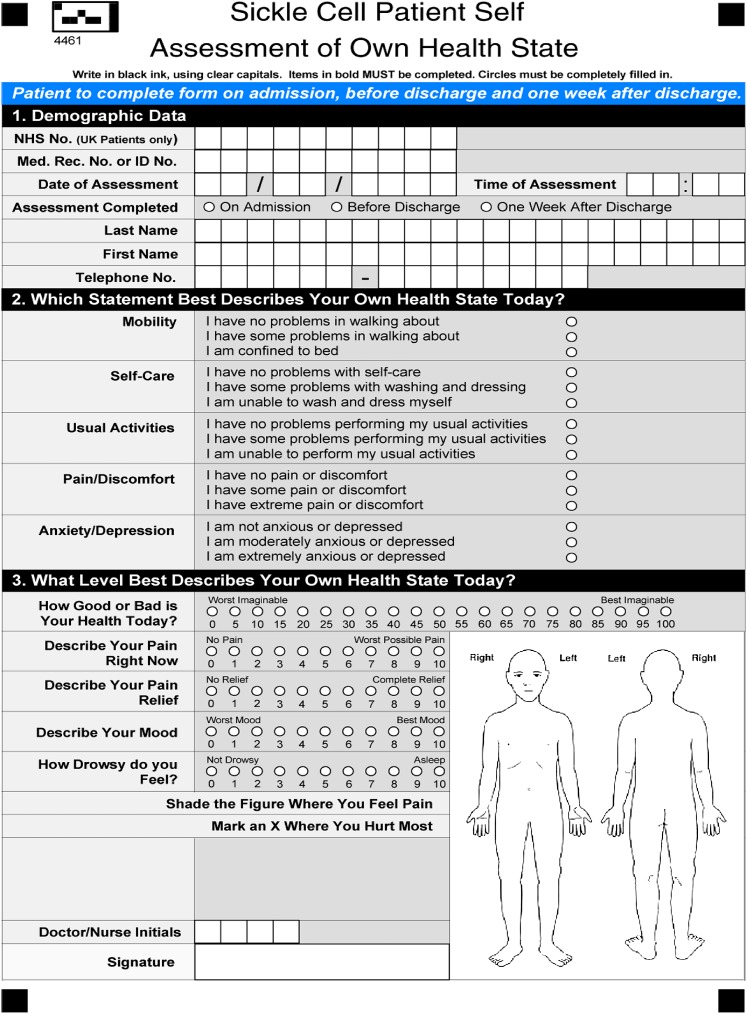

Figure 1.

Pain and health-related quality of life assessment form.

Objective

The main aim of the study was to define the relationship between adult patient self-reported sickle cell pain, mood and HRQoL across three time-points during and after hospital admissions. Using empirical data to explore and characterise this relationship could strengthen the case for biopsychosocial interpretation and a multidisciplinary approach to the clinical management of patients with SCD within an acute hospital setting, which incorporates psychological assessments and interventions.

Methods

This is a longitudinal hospital-based study examining data from a retrospective audit review. Therefore, no specific research questions or hypotheses were proposed, and formal ethics approval was not required. The ‘Sickle Cell Patient Self Assessment of Own Health State’ form comprises three sections (figure 1). The first section taken from the standardised EQ-5D measures HRQoL in five dimensions: mobility; self-care; usual activities; pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression at three levels (1) no problems, (2) some problems and (3) extreme problems. There is also a visual analogue scale to record self-rated health state on a scale of 0 (worst imaginable) to 100 (best imaginable). The second section is adapted from the Memorial Pain Assessment Card,9 a standardised measure of pain which provides ratings of pain intensity 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain), pain relief 0 (no relief) to 10 (complete relief), mood 0 (worst mood) to 10 (best mood) and drowsiness 0 (not drowsy) to 10 (asleep) on Visual Analogue Scales (VAS). The final section requires patients to indicate the location of their pain on a diagram of the body.

Data were extracted from a hospital computer server-based electronic system of consecutive cases of patients who were admitted over the 5-year period. The data set was deidentified by removal of patients' personal information for the purposes of the audit, and subsequent statistical analyses for the study. These included patients admitted to the hospital day-care centre and inpatient units via the Accident and Emergency (A&E) department. There were three assessment time-points: T1—on admission to hospital, T2—before discharge from hospital, T3—7 days postdischarge from hospital (telephone). Initial statistical analyses of demographic characteristics and clinical characteristics included all patients.

The relationship between pain and HRQoL was examined by combining all the data points across three time-points since this was of initial interest and unique to this study. Health utility values were calculated from the EQ-5D using a special calculator tool with data from various countries presented by Szende et al.10 UK health utility data are based on the time trade-off valuation method with weights derived from 3395 UK adults first reported by Kind et al.11 The relationship between pain score and EQ-5D-derived health utility was explored. Preliminary analysis showed that there was no significant interaction between time-point and pain score in predicting utility (ie, although pain score decreased and utility increased over time, the relationship between the two variables remained constant). Therefore, data from all three time-points were combined in a single analysis. This approach meant that it was necessary to account for within-person correlation, so a random-effects time-series regression model with patient ID as a panel variable was used (xtreg command in Stata V.8.0). Polynomial functions of pain score were explored to improve model fit. Patient age and sex were not significant predictors of utility (either as individual variables or in interaction with pain score), so these covariates were not included in the model.

Results

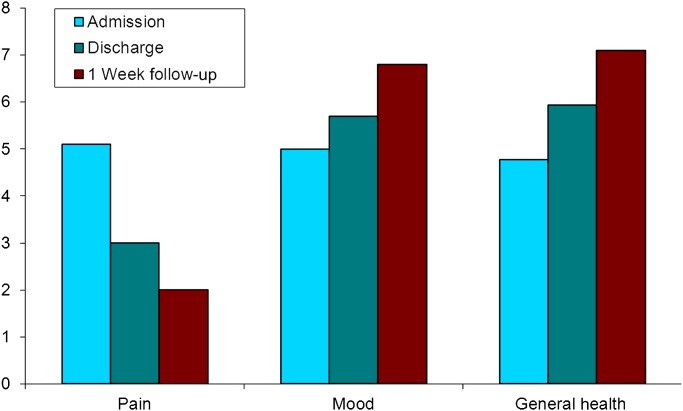

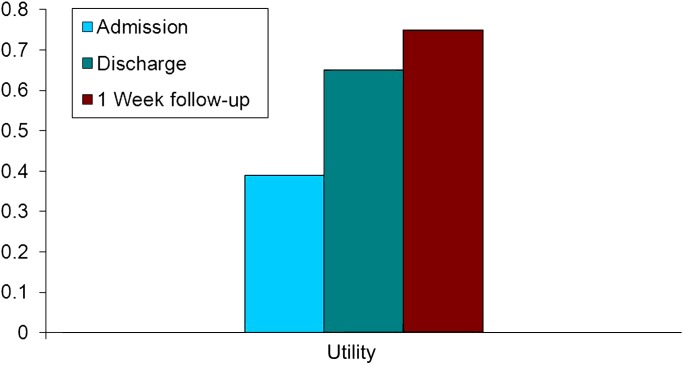

There were 510 admissions in total. Most of the patients had more than one hospital admission for acute sickle cell pain during the study period. Demographic characteristics of the patients are presented in table 1. Day-care cases were excluded from t test analyses and figures 2 and 3 (not from the utility analysis, figure 4, as described above). The average length of stay for inpatient hospital admissions with uncomplicated pain episodes at Central Middlesex Hospital is about 3 days, whereas patients treated in day care are discharged within the same day, meaning the data are not comparable hence day-care cases were removed from the analyses. Pain, mood and general health status scores obtained from inpatient cases are presented in figure 2; in addition, their health utility values obtained from the EQ-5D are presented in figure 3.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of adult patients with sickle cell disease

| Variable | Frequency |

| Gender | |

| Male | 199 (39%) |

| Female | 305 (60%) |

| Unreported | 6 (1%) |

| Location | |

| Inpatient | 463 (91%) |

| Day care | 47 (9%) |

| Mean (SD) | |

| Age | 28.9 (10.2) |

Figure 2.

Pain, mood and general health status scores of adult patients with sickle cell disease (general health scores are scaled down from 100 to 10).

Figure 3.

Health utility indices of adult patients with sickle cell disease.

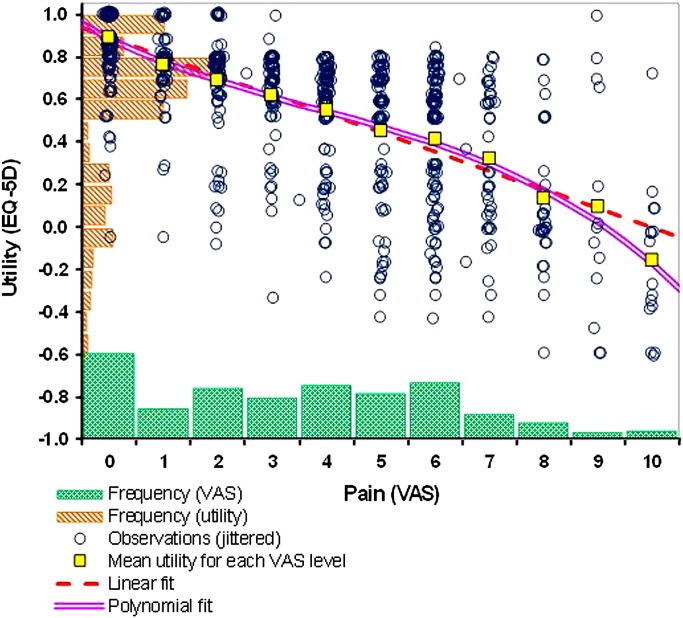

Figure 4.

Relationship between sickle cell pain and health utility. VAS, Visual Analogue Scales.

Pain

There was a significant reduction of pain VAS scores from admission T1 (mean 5.1, SD 2.5) to discharge T2 (mean 3.0, SD 2.4), t=9.29, df=482, p<0.001, and from discharge T2 to 1-week telephone follow-up T3 (mean 2.0, SD 2.2), t=4.69, df=427, p<0.001.

Mood

There was a significant improvement in mood VAS scores from admission T1 (mean 5.0, SD 2.2) to discharge T2 (mean 5.7, SD 2.3), t =−3.23, df =479, p=0.001, and from discharge T2 to 1 week follow-up T3 (mean 6.8, SD 2.2), t =−4.90, df =425, p<0.001.

General health status

Patients' reports of their general health on the VAS in addition showed significant improvements from admission T1 (mean 47.7, SD 22.3) through discharge T2 (mean 59.4, SD 21.7), t =−5.70, df =459, p<0.001, to 1-week follow-up T3 (mean 71.0, SD 20.0), t =−5.63, df =413, p<0.001.

HRQoL and health utility

Furthermore, health utility values derived from the EQ-5D showed that patients significantly got better between T1 (mean 0.39, SD 0.40) and T2 (mean 0.65, SD 0.29), t =−7.95, df =475, p<0.001, and from T2 to T3 (mean 0.75, SD 0.26), t =−3.94, df =421, p<0.001.

Pain and HRQoL/health utility

Figure 4 shows the relationship between pain and health utility for all patients across all three time-points combined. A simple linear model estimates the relationship as: utility =0.890−0.089pain (R2=0.437). A slightly better fit to the data was obtained by introducing square and cube functions to the model: utility =0.887−0.124pain + 0.014pain2−0.001pain3 (R2=0.445).

Discussion

Acute pain episodes are the hallmark of SCD. Furthermore, adults with SCD have been shown to have an impaired HRQoL as compared with the general population with pain and psychological distress being contributors.1 12 Unsurprisingly in this study, there was a significant reduction in pain scores from admission to discharge and at 1-week follow-up. Nonetheless, it was interesting to observe that patients were not completely pain free on discharge and importantly at 1-week follow-up. A large 6-month pain diary study of adult patients with SCD showed that 29% had sickle cell pain everyday.2 This supports the notion that acute pain episodes could develop into a type of chronic sickle cell pain. The ongoing prevalence of pain further highlights the need for a multidimensional approach to pain management that extends beyond hospitalisation and incorporates psychological interventions with coping strategies that can relieve pain and psychological distress while enhancing quality of life postdischarge.

Health utilities are cardinal values that reflect the preferences of an individual—or a society—for different health outcomes. They are measured on an interval scale with zero (0) reflecting states of health equivalent to death and one (1) reflecting perfect health. Some health states are considered to be worse than death and have a negative value. Combined with survival estimates, health utilities can be used to generate quality-adjusted life years for use in cost–utility analyses of medical treatment. The EQ-5D is one of the commonly used HRQoL instruments for measuring health utilities. In this study, HRQoL and health utility values improved over the three time-points. This demonstrates that, although HRQoL in patients with SCD is considerably impaired during acute painful episodes in hospital with improvements after discharge, daily function may not be restored for quite some time and steady-state HRQoL is likely to remain impaired. The mean health utility index of 0.75 at 1-week follow-up is similar to the mean health utility index of 0.72 obtained from SF-36 scores in a comparable UK community-based adult SCD population.1 Studies from USA have also reported similar HRQoL (SF-36) for people with SCD.12 13

Although a correlation between pain and health utility is clearly identifiable in our data set, it is subject to a substantial degree of variability at the individual level. For example, it can be seen in figure 4 that one participant rated their pain level as 9 out of 10, suggesting very intense discomfort, yet identified no health-state limitation on the EQ-5D questions (in the process, answering ‘I have no pain or discomfort’ for the pain dimension of the instrument). Nevertheless, on average, the expected negative correlation between pain score and health utility is observed.

When estimating health utility from pain score, it may be appropriate to prefer the polynomial model to the simple linear fit, on the mathematical basis that it provides a very marginally superior reflection data and also on the theoretical basis that it is more sensitive to high pain scores (producing lower estimated utility values). It is known that EQ-5D measurements are subject to ‘floor’ effects, and it is credible that most people would prefer death to the prospect of spending the rest of their lives with a pain score of 10 (ie, in the most excruciating pain imaginable); this is consistent with a utility value of less than zero for such health states.

Pain is an important dimension in the HRQoL of patients with SCD. Patients with sickle cell pain who are admitted to day care and through A&E seemed to have impaired HRQoL as a result of pain; however, this improved during the course of the admission and at home over 7 days after discharge. In general, HRQoL is a crucial aspect of illness perception from the patient's viewpoint, incorporating psychological, social and disease-related factors. In the absence of a universal cure in SCD, the primary aim of treatment is to reduce the impact of the disease (pain in this case), thus enhancing quality of life.

It should also be noted that HRQoL has a relationship with the psychological well-being and experience in patients with pain, and this is influenced by their coping strategies. These findings could have been influenced by such phenomena.

Mood changes in terms of anxiety and depression can be associated with sickle cell pain.14 15 General health status is also of importance because it affects the psychological well-being of the patient. Mood and general health improved through admission to 1-week follow-up. In addition to pain, these factors could contribute to length of stay in hospital and would be an interesting area for future research. People with long-term medical conditions including pain frequently use health services and are likely to have comorbid mental health problems such as depression and anxiety.16 The provision of psychological assessments and interventions, in an acute hospital setting, could improve health outcomes by facilitating the use of effective coping strategies1 and managing comorbid mood disorders. This could result in a reduced length of stay in hospital and a reduction in healthcare costs.17

Conclusions

The study yielded results suggesting that a multidimensional approach to the assessment and treatment of patients with SCD admitted to hospital is beneficial. This approach helps to identify problems for which psychological support is required during and after the hospital admission and is in accordance with National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline for the management of patients with chronic illnesses.18 Psychological interventions can be targeted at inpatients to enhance the use of appropriate pain coping techniques, alleviate any comorbid mental health difficulties and ultimately improve quality of life. Together with their usual treatment for sickle cell pain, this will help reduce length of stay and related hospital costs.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Anie KA, Grocott H, White L, et al. Patient self-assessment of hospital pain, mood and health-related quality of life in adults with sickle cell disease. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001274. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001274

Contributors: KAA conceived, designed the study and performed some statistical analyses. HG and LW were responsible for data collection and entry into the study database. GR and MD performed statistical analyses. GC was involved in the study oversight. KAA took the lead in the write up with review and editing by HG, GR, MD and GC. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: KAA was a co-opted expert to the NICE Guideline Development Group for the Sickle Cell Acute Painful Episode. The authors declare that there is no support from any organisation for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: None.

References

- 1.Anie KA, Steptoe A, Bevan DH. Sickle cell disease: pain, coping, and quality of life in a study of adults in the UK. Br J Health Psychol 2002;7:331–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith WR, Penberthy LT, Bovbjerg VE, et al. Daily assessment of pain in adults with sickle cell disease. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:94–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brozović M, Davies SC, Brownell AI. Acute admissions of patients with sickle cell disease who live in Britain. Br Med J 1987;294:1206–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapiro BS, Benjamin LJ, Payne R, et al. Sickle cell-related pain: perceptions of medical practitioners. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997;14:168–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anie KA, Steptoe A. Pain, mood and opioid medication use in sickle cell disease. Hematol J 2003;4:71–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pasero C, Paice JA, McCaffery M. Basic mechanics underlying the causes and effects of pain. In: McCaffery M, Pasero C, eds. Pain: Clinical Manual. St. Louis: Mosby, Inc, 1999:15–34 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benjamin L. Pain management in sickle cell disease: palliative care begins at birth? Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2008:466–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The EuroQol Group EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fishman B, Pasteranak S, Wallenstien SL, et al. The memorial pain assessment card: a valid instrument for the evaluation of cancer pain. Cancer 1987;60:1151–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szende A, Oppe M, Devlin N. eds. EQ-5D Value Sets: Inventory, Comparative Review and User Guide. EuroQol Group Monographs Volume 2. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kind P, Hardman G, Macran S. UK Population Norms for EQ-5D. York Centre for Health Economics, Discussion Paper. York, UK: University of York, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClish DK, Penberthy LT, Bovbjerg VE, et al. Health related quality of life in sickle cell patients: the PiSCES project. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2005;3:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woods KF, Miller MD, Johnson MH, et al. Functional status and well-being in adults with sickle cell disease. J Clin Outcomes Manag 1997;4:15–21 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gil KM, Carson JW, Porter LS, et al. Daily mood and stress predict pain, health care use, and work activity in African American adults with sickle-cell disease. Health Psychol 2004;23:267–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porter LS, Gil KM, Carson JW, et al. The role of stress and mood in sickle cell disease pain: an analysis of daily diary data. J Health Psychol 2005;5:53–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapman DP, Perry GS, Strine TW. The vital link between chronic disease and depressive disorders. Preventing Chronic Dis 2005;3:1–3 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiles JA, Lambert MJ, Hatch AL. ‘The impact of psychological interventions on medical cost offset: a meta-analytic review’. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 1999;6:204–20 [Google Scholar]

- 18.NICE Clinical Guideline 91 Depression In Adults With A Chronic Physical Health Problem. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.