Abstract

An increasing body of evidence suggests that tumors might originate from a few transformed cells that share many properties with normal stem cells. However, it remains unclear how normal stem cells are transformed into cancer stem cells. Here, we demonstrated that mutations causing the loss of tumor suppressor Sav or Scrib or activation of the oncogene Ras transform normal stem cells into cancer stem cells through a multistep process in the adult Drosophila Malpighian Tubules (MTs). In wild-type MTs, each stem cell generates one self-renewing and one differentiating daughter cell. However, in flies with loss-of-function sav or scrib or gain-of-function Ras mutations, both daughter cells grew and behaved like stem cells, leading to the formation of tumors in MTs. Ras functioned downstream of Sav and Scrib in regulating the stem cell transformation. The Ras-transformed stem cells exhibited many of the hallmarks of cancer, such as increased proliferation, reduced cell death, and failure to differentiate. We further demonstrated that several signal transduction pathways (including MEK/MAPK, RhoA, PKA, and TOR) mediate Rasṕ function in the stem cell transformation. Therefore, we have identified a molecular mechanism that regulates stem cell transformation, and this finding may lead to strategies for preventing tumor formation in certain organs.

Keywords: Drosophila, Malpighian Tubules, Stem cell, Cancer stem cell, Tumor suppressor, Sav, Scrib, Oncogene, Ras

Introduction

Recent studies suggest that tumors may originate from a few transformed cells with stem-cell characteristics, called cancer stem cells (Reya et al., 2001; Kim and Dirks, 2008). This hypothesis is based on observations that some solid tumors and leukemias contain small numbers of self-renewing cells that can re-generate an entire tumor mass when transplanted into mice (Al-Hajj et al., 2003; Lapidot et al., 1994; OṕBrien et al., 2007; Ricci-Vitiani et al., 2007; Singh et al., 2004). In the brain, these cancer stem cells often express markers of normal stem cells and remain dependent on the niche microenvironments that regulate normal stem cells (Calabrese et al., 2007). In mouse intestine, normal stem cells are the cells-of-origin for cancer and are susceptible to neoplastic transformation (Barker et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2009). Conventional cancer therapies designed to block cell proliferation may not always affect these stem cells, due to their unique properties (Michor et al., 2005). Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanisms of stem cell regulation and transformation is an important prerequisite for developing new therapeutic strategies.

Besides the germline stem cells systems, the Drosophila adult stem cells such as intestinal stem cells (ISCs) are emerging as an important model to study genes and signal regulating the tissue homeostasis in steady-state and challenging condition (Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006; Ohlstein and Spradling, 2006; Buchon et al., 2009; Jiang et al., 2009; Cronin et al., 2009; Amcheslavsky et al., 2009; Chatterjee and Ip, 2009.) We identified that the adult Malpighian Tubules (MT) is maintained by multipotent RNSC in Drosophila (Singh et al., 2007). The Malpighian Tubules (MTs) of Drosophila, which function as the fly kidney, is another model system for studying adult stem cell regulation and transformation in a genetic model organism (Singh et al., 2007). The adult Drosophila has two pairs of MTs, a long anterior pair and a short posterior pair, which converge onto the alimentary canal through common ureters (Pugatcheva and Mamon, 2003; Sözen et al., 1997; Wessing and Eichelberg, 1978). Each tubule of the longer anterior pair can be divided into four compartments: initial, transitional, main (secretory), and proximal (reabsorptive). The last of these can be further divided into a lower tubule and a ureter. We recently identified multipotent renal and nephric stem cells (RNSCs) among the “tiny” cells in the lower tubules and ureters of the MTs (Singh et al., 2007). An RNSC can produce a new RNSC and an immature daughter, a renablast (RB), through asymmetric division. The RB has two potential fates. In the region of the lower tubules and ureters, the RB can become a mature renalcyte (RC) in about 5 days, through endoreplication. Alternatively, the RB can move toward the distal upper tubules and differentiate into a type I or II cell in the transitional and initial segments. In addition, autocrine JAK-STAT signaling regulates the self-renewal of these stem cells (Singh et al., 2007).

Here, we screened for mutants that affect RNSC self-renewal and differentiation, using the positively marked mosaic lineage (PMML) labeling technique (Kirilly et al., 2005) and the MARCM (mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker) system (Lee and Luo, 1999). These screens revealed that mutations causing the loss of tumor suppressor Scribble (Scrib) or Salvador (Sav) function or the constitutive activation of the Ras oncogene caused RNSC overproliferation and resulted in tumor growth. Genetic experiments suggested that Ras functions downstream of Scrib and Sav in regulating stem cell transformation. We further analyzed the genes and signal transduction pathways that might mediate Rasṕ function in RNSC transformation. Our results suggested that Scrib/Sav and Ras transform RNSCs by a multistep process involving several signal transduction pathways.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila Stocks

All crosses were done at 25°C unless otherwise indicated. The following fly stocks used in this study were described in FlyBase unless otherwise specified: hs-FLP UAS-srcEGFP, FRT52B (y) (yellow-FRT-Gal4), and FRT52B(w)(white-Actin5C-FRT) UAS-EGFP were provided by T. Xie; UAS-DaPKCCAAXWT and UAS-DaPKCΔN were provided by C. Doe and S. Campuzano; Cyclin E-LacZ and hpo42-47 were provided by D. J. Pan; UAS-RafK497M was provided by M. Stern; DcoB3 was provided by D. Kalderon; FRT82B-Scrib1 and FRT82B-Scrib2 were provided by D. Bilder; FRT82B-Sav3 and FRT82B-wtslatsX1 were provided by I. Hariharan; savshrp-5 and savshrp-6 were provided by G. Halder; UAS-RasV12, UAS-RafGof, UAS-PI3KDN, UAS-RhoAN19, UAS-RhoAV14, Pnt-LacZ, Diap-LacZ, DaPKC k06403 , lgl4, TorΔP, Stat92Ej6C8, FRT82B piM, AyGal4 UAS-GFP, FRT40A-tub-Gal80, FRTG13-tub-Gal80, FRT82B-tub-Gal80, SM6, hs-Flp, and TM3, Sb, hs-Flp were obtained from Bloomington stock center; All UAS-RANi lines were obtained from the VDRC stock center.

Generate GFP-marked RNSC clones

To generate GFP-marked mutant clones using the MARCM system, flies with the following genotypes were used:

FRT40A UAS-RasV12, TorΔP/FRT40A-tub-Gal80; AyGal4 UAS-GFP/TM3, Sb, hs-Flp

FRT40A UAS-RasV12, DcoB3 /FRT40A-tub-Gal80; AyGal4 UAS-GFP/TM3, Sb, hs-Flp

FRTG13 DaPKCK06403 /FRTG13-tub-Gal80; AyGal4 UAS-GFP/TM3, Sb, hs-Flp

FRTG13 UAS-RasV12, DaPKCK06403 /FRTG13-tub-Gal80; AyGal4 UAS-GFP/TM3, Sb, hs-Flp

SM6, hs-Flp/ AyGal4 UAS-GFP; FRT82B-tub-Gal80/ FRT82B piM

SM6, hs-Flp/ AyGal4 UAS-GFP; FRT82B-tub-Gal80/ FRT82B RasC40b

SM6, hs-Flp/ AyGal4 UAS-GFP; FRT82B-tub-Gal80/ FRT82B Scrib1

SM6, hs-Flp/ AyGal4 UAS-GFP; FRT82B-tub-Gal80/ FRT82B Sav3

SM6, hs-Flp/ AyGal4 UAS-GFP; FRT82B-tub-Gal80/ FRT82B UAS-RasV12

SM6, hs-Flp/ AyGal4 UAS-GFP; FRT82B-tub-Gal80/ FRT82B UAS-RasV12, Stat92Ej6C8

SM6, hs-Flp/ AyGal4 UAS-GFP; FRT82B-tub-Gal80/ FRT82B RasC40b, Scrib1

SM6, hs-Flp/ AyGal4 UAS-GFP; FRT82B-tub-Gal80/ FRT82B RasC40b, Sav3

To generate GFP-marked clones that overexpressed certain genes using the PMML system, flies with the following genotypes were used:

hs-Flp UAS-srcEGFP/+; FRT52B(w) UAS-EGFP/ FRT52B(y)

hs-Flp UAS-srcEGFP/+; FRT52B(w) UAS-EGFP/ UAS-RasV12 FRT52B(y)

hs-Flp UAS-srcEGFP/+; FRT52B(w) UAS-EGFP/ FRT52B(y); UAS-RafGof/+

hs-Flp UAS-srcEGFP/+; FRT52B(w) UAS-EGFP/ FRT52B(y);UAS-DaPKCCAAXWT/+

hs-Flp UAS-srcEGFP/+; FRT52B(w) UAS-EGFP/ UAS-RhoAV14 FRT52B(y)

hs-Flp UAS-srcEGFP/+; FRT52B(w) UAS-EGFP/ UAS-RasV12 FRT52B(y); UAS-RhoAN19/+

hs-Flp UAS-srcEGFP/+; FRT52B(w) UAS-EGFP/ UAS-RasV12 FRT52B(y); UAS-RafK497M/+

hs-Flp UAS-srcEGFP/+; FRT52B(w) UAS-EGFP/ UAS-RasV12 FRT52B(y); UAS-PI3KDN /+

hs-Flp UAS-srcEGFP/+; FRT52B(w) UAS-EGFP/ UAS-RasV12 FRT52B(y); UAS-Dsor1 RNAi/+

hs-Flp UAS-srcEGFP/+; FRT52B(w) UAS-EGFP/ UAS-RasV12 FRT52B(y); UAS-other RNAi/+

One- or two-day-old adult females with the correct genotype were heat-shocked once (for PMML) or six times (for MARCM) (37°C, 60 min) for three consecutive days, with an interval of 8–12 hours between heat shocks. The flies were transferred to fresh food daily after heat shock, and their MTs were processed for staining at the indicated times.

Immunofluorescence staining and microscopy

The MTs were dissected in cold PBS and fixed for 30 min in 4% formaldehyde in PBS. After several washes with PBT (PBS plus 0.1% Triton X-100), the samples were preabsorbed in 5% normal goat serum in PBT overnight at 4°C. The MTs were then incubated in primary antibody diluted in PBT for 2 hours at room temperature. After several washes with PBT, the MTs were incubated with secondary antibody diluted in PBT for 1 hour at room temperature. After several more washes with PBT, the MTs were mounted in Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI. Confocal images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM510 system, and processed using Adobe Photoshop CS3.

The following antibodies were used: rabbit polyclonal anti-STAT92E antibody (1:1000); rabbit polyclonal anti-dMyc antibody (1:2000; gift from D. Stein); rabbit polyclonal anti-DaPKC antibody (1:200; Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA); rabbit polyclonal anti-Baz antibody (1:1000; gift from A. Wodarz); rabbit polyclonal anti-Scrib antibody (1:1000; gift of C. Doe); rabbit polyclonal anti-YKI antibody (1:1000; gift of D. J. Pan); rabbit polyclonal anti-pCdc2 antibody (1:500; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA); rabbit polyclonal anti-pH3 antibody (1:500; Upstate, Lake Placid, NY); Chicken polyclonal anti-GFP antibody (1:3000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA); mouse monoclonal anti-β-Gal antibody (1:200; Clontech, Mountain View, CA); rat monoclonal anti-DE-cadherin antibody (1:50; gift from T. Uemura); mouse monoclonal anti-Armadillo N7A1 (1:20; DSHB); mouse monoclonal anti-Cyc E (1:5; gift from H. Richardson); mouse monoclonal anti-DIAP (1:50; gift from B. Hay); mouse monoclonal anti-D-pERK (1:50, Sigma, St Louis, MO); mouse monoclonal anti-γ-tubulin (1:50, Sigma). Secondary Abs were goat anti-mouse, goat anti-rat, goat anti-rabbit, and goat anti-chicken IgG conjugated to Alexa 488, Alexa 568, or Alexa 633 (1:500; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Results

Tumor suppressors Scrib and Sav control the proliferation and fate determination of stem cells in adult Drosophila MTs

To identify genes that regulate stem cell self-renewal and differentiation in adult Drosophila MTs and posterior midgut, we screened genes that are known to play important roles in cell-fate regulation in other systems, using both the PMML (Kirilly et al., 2005) and the MARCM system (Lee and Luo, 1999). These methods allow the generation of an individual homozygous mutant (the MARCM system) or the overexpression (the PMML technique) of stem cell clones that express GFP in an otherwise heterozygous, GFP-negative background. From these screens, we found that the loss-of-function mutation of Scrib or Sav or the activation of Ras caused RNSCs/RBs overproliferation and resulted in tumor growth.

The RNSCs in the adult Drosophila MTs are small diploid cells in the region of the lower tubules and ureters (Singh et al., 2007). In wild-type MTs, an RNSC can produce a new RNSC and an immature diploid daughter RB, through asymmetric division. The RB can become a mature RC in the lower tubules and ureters. The RCs are polyploid, with a large nucleus. Both RNSCs and RBs are diploid with a small nucleus, express Stat92E protein, and are Armadillo (Arm) and DE-Cadherin (DE-Cad) positive. The only known detectable difference between RNSCs and RBs is that the JAK-STAT signaling (measured by a Stat92E-GFP reporter) is stronger in RNSCs than in RBs (Singh et al., 2007). However, since it is still very difficult to distinguish RNSCs from RBs precisely, we will discuss them together as RNSCs/RBs.

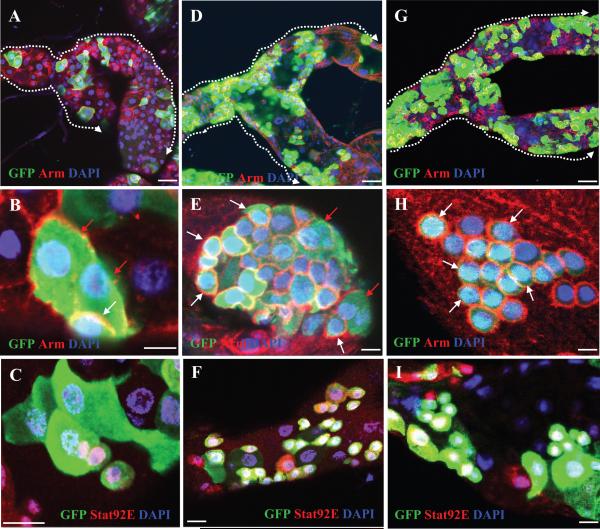

We generated GFP-positive marked clones in the MTs of wild-type controls or scrib (scrib1) or sav (sav3) strong loss-of-function mutants using the MARCM system (Lee and Luo, 1999; Figure 1). In the wild-type MT, GFP-marked clones were rare, and usually only a few clusters appeared in each pair of MTs (Figure 1A). Each control GFP+ clone usually but not always had one RNSC and one RB (i.e., small nucleus, diploid, Arm and Stat92E positive; Figure 1B and C, white arrow) and several RCs (i.e., large nucleus, polyploid, Arm and Stat92E negative; Figure 1B and C, red arrows; Figure S1D and G) 6 days after clonal induction (ACI). In contrast, there were many GFP-marked clones in the scrib and sav mutants, and usually lots of clusters were seen in each pair of MTs (Figure 1D and G). These MTs were significantly enlarged (supporting information (SI) Figure S1B and C), and their mitotic index was significantly increased compared to wild-type clones (0.76 for n=17 MTs with wild-type clones compared to 4.57 for n=14 MTs with scrib clones and 4.33 for n=12 MTs with sav clones). Each GFP+ mutant cluster typically contained multiple RNSCs/RBs (diploid, Arm and Stat92E positive; Figure 1E, F, H and I; Figure S1E, F, H and I) and a few RCs (polyploid, Arm and Stat92E negative; Figure 1E, F, H, and I). The proportion of GFP+ cells that were RNSCs/RBs was significantly increased in both the scrib and sav mutant clones compared with wild-type clones. The average ratio of RNSCs/RBs to RCs was 11.1:1 (611/55) in 6 MTs with scrib mutant clones, 10.8:1 (522/51) in 6 MTs with sav mutant clones, and 0.88:1 (50/57) in 5 MTs with wild-type clones. We conclude that, while wild-type RNSCs go through an asymmetric division to generate one RNSC and one RB, scrib and sav mutant RNSCs often result in increased RNSC/RB production, and that while wild-type RNSCs are relatively quiescent and only divide infrequently, scrib and sav mutant RNSCs are more active and divide frequently.

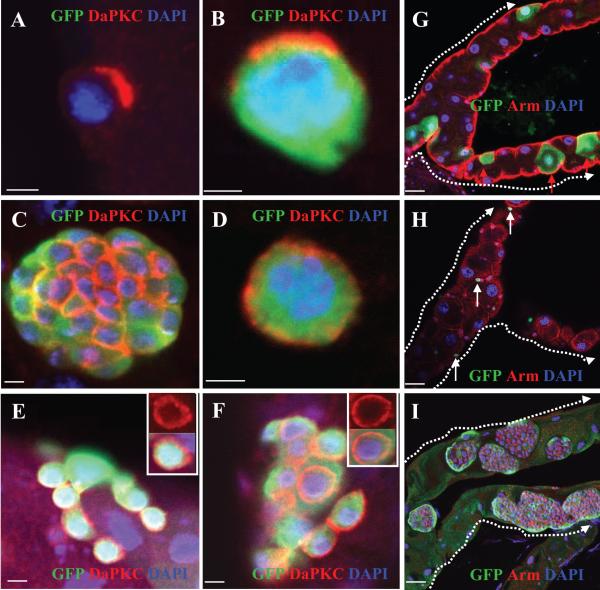

Figure 1.

The tumor suppressors Scrib and Sav regulate RNSC proliferation.

MTs with GFP-marked wild-type (A-C), scrib1 (D-F), and sav3 (G-I) MARCM clones, were stained with the indicated antibodies. White arrows indicate RNSCs, while red arrows indicate the large RCs in (B, E, and H). Dashed arrows in (A, D, G) point from the ureter to the upper tubules. Scale bars in (A, D, G) represent 10 μm; in all other panels represent 5 μm.

We also analyzed mutant clones of other components in the Scrib and Sav pathways. In the Scrib pathway, we analyzed either strong or null mutant alleles (Bilder et al., 2000) of lethal giant larvae (lgl4) and disc-large (dlgm52); in the Sav pathway, we analyzed either strong or null mutant alleles (Harvey et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2003) of warts (wtslatsX1) and hippo (hpo42-47). Among these mutants, only RNSC clones of wtslatsX1 significantly overproliferate as seen in RNSC clones of scrib1 and sav3 (Figure S2A, B, and data not shown), suggesting that either only selective members in these two pathways regulate RNSC self-renewal or other genes compensate loss-of function of lgl, dlg, and hpo in regulating RNSCs.

We also examined protein expression of Scrib and Yorkie (YKI, a downstream transcriptional coactivator in the Sav pathway). Scrib is mainly expressed in differentiated RCs while YKI is expressed in both RNSCs/RBs and RCs (Figure S2C and D). The Scrib and Sav pathways may function to block RNSC differentiation.

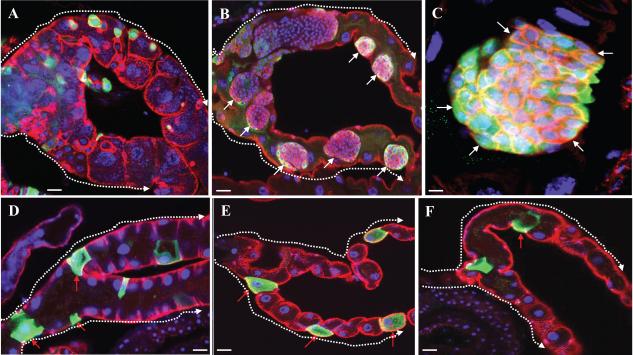

The oncogene Ras functions downstream of Scrib and Sav to regulate RNSC transformation

Mutations that activate the oncogene Ras have been identified in more than 30% of all types of human tumors (Barbacid, 1987). We found that activation of the oncogene Ras caused RNSC overproliferation and resulted in tumorous growth in MTs (Figure 2). We generated GFP-positive marked clones in wild-type control MTs or in MT cells expressing a constitutively activate form of Ras (RasV12) using the MARCM technique (Lee and Luo, 1999; Figure 2). In the wild type MTs, the GFP+ clones were rare and usually only a few clusters were seen in the lower tubules and ureters of each pair of MTs (Singh et al 2007; Figure 2A) 6 days ACI; each cluster usually contained one RNSC and one RB (both are diploid, Arm-positive, DE-Cad-positive, and Stat92E-positive) and several RCs (polyploid, Arm-negative, DE-Cad-negative, and Stat92E-negative) (Figure 2A, 3B, and 3D). In contrast, GFP+ cells in MTs expressing constitutively activate Ras, formed large tumorous masses in the lower tubules, ureters, and main segments (Figure 2B, 2C, 3A, and 3C). All the cells in the RasV12 clones had a small nucleus (diploid) and coexpressed Arm, DE-Cad, and Stat92E (Figure 2B, 2C, 3A, and 3C). The mitotic index of the RasV12 clones was significantly greater than that of the wild-type clones (0.96 for n=14 MTs with wild-type clones compared to 20.44 for n=16 MTs with RasV12 clones). No differentiated RCs were detected in the RasV12 clones (Figure 2B, 2C, 3A, and 3C). These observations suggest that activation of the Ras oncogene results in RNSCs that overproliferate and fail to differentiate.

Figure 2.

The oncogene Ras functions downstream of Scrib and Sav in regulating RNSC transformation.

GFP+ clones were generated in the MTs of flies of the indicated genotypes by the MARCM technique and stained with the indicated antibodies. A, Wild-type control clones generated in the FRT82B piM MTs. B and C, UAS-RasV12 mutant clones. D, RasC40b mutant clones. E, RasC40b, scrib1 mutant clones. F, RasC40b, sav3 mutant clones. Green: GFP; red: Arm; blue: DAPI. White arrows indicate RNSCs; red arrows indicate the large RCs. Dashed arrows in (A, B, D, E, F) point from the ureter to the upper tubules. Scale bars in (A, B, D, E, F) represent 10 μm; in C represents 5 μm.

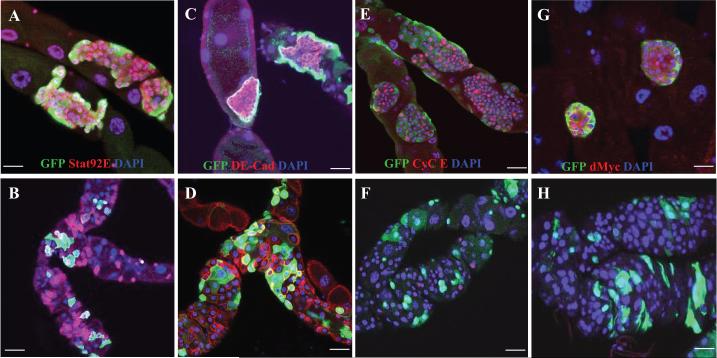

Figure 3.

Activated Ras blocks the differentiation and promotes the proliferation of RNSCs.

GFP+ clones were generated in the MTs of RasV12 (A, C, E, G) or wild-type (B, D, F, H) flies by the PMML technique and stained with the indicated antibodies. Scale bars in A, C, E, and G represent 7.5 μm; Scale bars in B, D, F, and H represent 10 μm.

To determine Rasṕ function in regulating RNSCs under physiological conditions, we generated clones in a Ras-null mutant (RasC40b; Hou et al., 1995) using the MARCM system (Lee and Luo, 1999). Marked clones homozygous for the Ras-null mutants were generated in the MTs and identified by GFP expression. Only a few differentiated RCs (4.86 RCs and 0.29 RNSC/RBs for n=7 MT with RasC40b clone compared to 11.40 RCs and 10.00 RNSC/RBs for n=5 MT with wild-type clone) (large nucleus and Arm negative) were detected in the Ras-null mutant MTs (Figure 2D). Together with the above results from mutants with activated Ras, these Ras-null phenotypes suggested that normal Ras signaling promotes RNSC proliferation and blocks stem-cell differentiation.

To determine the epistatic relationships between Ras and the tumor suppressors scrib and sav, we generated double-mutant clones of RasC40b scrib1 or of RasC40b sav3 using the MARCM system. All of these double-mutant clones had only a few differentiated RCs (Figure 2E and F; larger nucleus and Arm negative), like the single Ras-null mutant, suggesting that Ras functions downstream or parallel of the two tumor suppressors in regulating RNSC fate.

Scrib cooperates with a Ras gain-of-function mutation to promote tumor progression and cell invasion in Drosophila imaginal tissues (Brumby and Richardson, 2003; Pagliarini and Xu, 2003), and human Scrib cooperates with H-Ras to promote cell invasion in mammalian cultured cells (Dow et al., 2008). To examine whether the constitutively-active RasV12 would cooperate with loss-of-function Scrib or Sav mutants in regulating RNSC transformation, we generated double mutant clones of RasV12 scrib1 or RasV12 sav3, using the MARCM system. All these double mutant clones looked exactly like the RasV12 mutant clones, and no additional phenotypes were observed (data not shown). We also transplanted the GFP+ double-mutant RNSCs into the abdomen of wild-type adult hosts and found that the transformed stem cells (just like the RasV12-transformed RNSCs) rapidly proliferated, and never migrated to other organs, suggesting that they are not metastatic tumors. Together, these findings suggested that the two tumor suppressors function upstream or parallel of Ras and do not cooperate with Ras to promote tumor progression or cell invasion in MTs.

The Ras-transformed stem cells exhibit hallmarks of cancer

We assayed additional markers to distinguish the normal RNSCs and transformed RNSCs caused by the loss-of-function mutation of scrib or sav or activated Ras. We found that regulators of the cell cycle and proliferation, Cyclin E (Cyc E), phosphorylated Cdc2 (pCdc2), Drosophila Myc (dMyc), and phosphorylated ERK (pERK), were barely expressed in normal RNSCs but were very strongly expressed in the RasV12-transformed RNSCs (Figure 3E-H, Fig. 4A-B, and Figure S3A); however, a transcriptional reporter of cyc E (cycE-lacZ; Duman-Scheel et al., 2002) was not expressed in either normal or RasV12-transformed RNSCs (Figure S3B; data not shown), suggesting that the elevated Cyc E in the transformed RNSCs was not due to an increase in cyc E transcription.

Figure 4.

Activated Ras blocks the cell death and promotes the migration of RNSCs. GFP+ clones were generated in the MTs of RasV12 (A, C, E) or wild-type (B, D, F) flies by the PMML technique and stained with the indicated antibodies. Scale bars in A, C, and E represent 7.5 μm; Scale bars in B, D, and F represent 10 μm.

Reduced cell death is another hallmark of human cancer. We observed that the apoptosis inhibitor DIAP and its transcriptional reporter diap1-lacZ (Ryoo et al., 2002) were dramatically elevated in the RasV12-transformed RNSCs compared with their levels in wild-type RNSCs (compare Figure 4C with D and 4E with F). We also directly examined cell death in MTs containing GFP+ clones homozygous for RasV12, using an Apoptag kit, and did not detect any cell death (data not shown).

In Drosophila larval neuroblasts, disrupting the cell polarity impairs fate specification during stem-cell division and eventually drives the neuroblasts into malignancy (Gonzalez, 2007). We examined the distribution of two cell-polarity markers, Bazooka (Baz) and Drosophila atypical protein kinase C (DaPKC), and found that all of the Ras-transformed RNSCs showed uniform cortical Baz and DaPKC expression, but in the wild-type RNSCs, these proteins formed an apical crescent (compare Fig. 5C and D with A and B; compare Fig. S4A with B), indicating that the activated Ras disrupted RNSC polarity and maybe asymmetric division as well.

Figure 5.

Change in cell polarity alone is insufficient to transform RNSCs.

GFP+ clones were generated in the MTs of flies of the indicated genotypes by the MARCM (B-G and I) or the PMML (H) technique and stained with the indicated antibodies. A and B, Wild-type MT and control clones generated in the FRT82B piM MTs. C and D, UAS-RasV12 mutant clones. E, scrib1 mutant clones. F, sav3 mutant clones. G, DaPKCk06403 mutant clones. H, UAS-DaPKCCAAXWT mutant clones. I, UAS-RasV12, DaPKCk06403 mutant clones. White arrows in H indicate RNSCs; red arrows in G indicate the large RCs. Dashed arrows in (G, H, I) point from the ureter to the upper tubules. Scale bars in (A-F) represent 5 μm; in (G-I) represent 10 μm.

In Drosophila imaginal discs, loss of the class I tumor suppressor Sav results in increased transcription of cyc E and diap1, leading to increased proliferation and reduced apoptosis (Brumby and Richardson, 2005; Saucedo and Edgar, 2007), whereas loss of the class II tumor suppressor Scrib mostly disrupts the apical-basal polarity of the epithelial cells, leading to increased proliferation and failure to differentiate (Brumby and Richardson, 2005; Bilder, 2004). We examined all of the above markers, and found no significant changes in the Cyc E, dMyc, pCdc2, pERK, or DIAP levels in the mutant scrib or sav clones, compared with wild-type RNSCs (data not shown). However, the two cell-polarity markers, Baz and DaPKC, showed uniform cortical distribution in the scrib and sav mutant RNSCs (Figure 5E and F; Baz data not shown).

In summary, RasV12-transformed RNSCs show increased proliferation, reduced apoptosis, disrupted cell polarity, and a failure to differentiate, while the scrib and sav mutant RNSCs show only increased proliferation and disrupted cell polarity, and perhaps ectopic self-renewing divisions that generate more stem cells. Thus, the RasV12-transformed RNSCs share many of the hallmarks of human cancer.

A simple change in RNSC polarity is not sufficient for their transformation

Apically localized DaPKC is an important regulator of the asymmetric division of larval neuroblasts. Overexpression of a constitutively active form, DaPKC-CAAX (a membrane-targeted version of DaPKC) causes the ectopic localization of DaPKC to both the apical and basal cortex, disrupting the neuroblastsṕ asymmetric division, and resulting in stem-cell tumor formation (Lee et al., 2006). In wild-type RNSCs, DaPKC formed an apical crescent (Figure 5A and B), but was uniformly distributed in the cortex of scrib and sav mutant RNSCs (Figure 5E and F) and in RNSCs expressing constitutively active Ras (Figure 5C and D). These observations raised the interesting possibility that the tumorous growth of RNSCs with these mutations might result from the ectopic localization of DaPKC on the cortex. To examine this possibility, we first generated DaPKC mutant clones using the MARCM system. We found that all the DaPKC mutant RNSCs differentiated into RCs (large nucleus and Arm negative; Figure 5G). We also generated clones that expressed two constitutively active forms of DaPKC (DaPKCCAAXWT and DaPKCΔN), using the PMML technique, and observed only a few GFP-positive RNSCs/RBs (diploid and Arm positive; Figure 5H and data not shown) in clones of the two constitutively active forms of DaPKC. Since the loss of DaPKC resulted in RNSC differentiation, and the constitutive activation of DaPKC blocked RNSC proliferation and differentiation, these results suggest that DaPKC may regulate RNSC asymmetric division. However, unlike its function in neuroblasts, the constitutive activation of DaPKC did not result in RNSC overproliferation and tumor formation. We also generated DaPKC RasV12 double mutant clones, and found that the loss of DaPKC did not suppress the tumors generated by RNSCs expressing constitutively active Ras (Figure 5I).

We further examined Baz expression during the cell cycle of RNSCs (Figure S4). Baz formed an apical crescent in non-dividing RNSCs (Figure S4C and L). During metaphase and early anaphase, Baz showed uniform cortical distribution (Figure S4D-F). During late anaphase and cytokinesis, Baz concentrated at the junctions that separate the two newly-formed cells (Figure S4G-I). In larval neuroblasts, Baz formed an apical crescent at metaphase (Figure S4J and K) and is directly co-related with asymmetric cell division. In RNSCs, Baz distribution changes according to cell activation and is not directly co-related with asymmetric cell division.

The above data together suggest that the expression of DaPKC and Baz proteins in RNSCs may serve as an indicator of RNSC activation and is not directly co-related with stem cell asymmetric division. Ras transforms RNSCs by a mechanism independent of DaPKC.

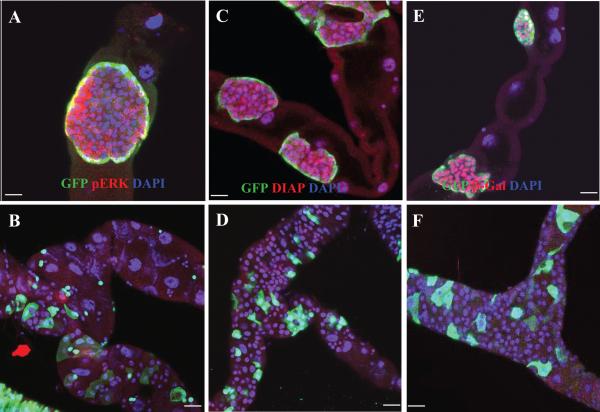

Signaling Downstream of Ras regulates RNSC Transformation

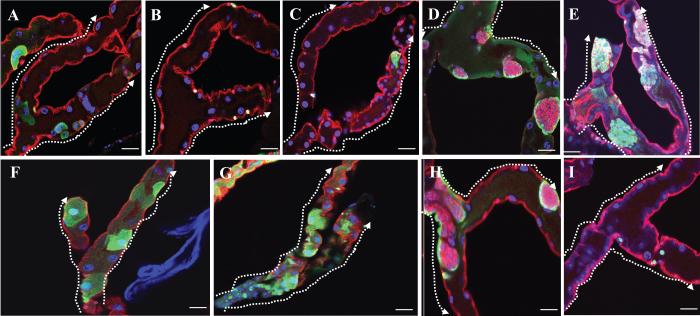

Ras has many downstream effectors that regulate complex signaling networks (Repasky et al., 2004). To identify the signal transduction pathways that mediate Rasṕ function in RNSC transformation, we screened UAS-transgenes available from public stock centers that express either a dominant-negative form or RNAi of a known signal transduction component. We found that the expression of a dominant-negative form of Raf or Rho A or an RNAi of MEK (Dsor1) suppressed the RasV12 phenotypes (Figure 6A-C). In contrast, the expression of a dominant-negative form of Ral, PI3K, Bsk, or Rac1, or an RNAi of cyc E or dMyc did not affect the RasV12 phenotypes (Figure 6D; data not shown). We also found that the loss of PKA or Tor blocked the RasV12-induced RNSC tumor formation but the loss of Stat92E did not affect the RasV12 phenotype (Figure 6E-G). We further found that the expression of a dominant-negative form of Rho A alone blocked RNSC proliferation (Figure S5C) and the expression of an RNAi of MEK (Dsor1) alone promoted RNSC differentiation (Figure S5D; 9.50 RCs and 1.25 RNSC/RBs for n=4 MT). The expression of an RNAi of MEK (Dsor1) also suppressed RNSC oveproliferation phenotype associated with unpaired (upd) overexpression (compare Figure S5B with 5A), further suggesting that the Ras/MEK pathway functions downstream of the JAK-STAT pathway in regulating RNSC self-renewal.

Figure 6.

Several signal transduction pathways cooperatively mediate Rasṕ function in RNSC transformation.

GFP+ clones were generated in the MTs of flies of the indicated genotypes by the PMML (A-D and F-I) or the MARCM (E) technique and stained with anti-GFP (green) and anti-Arm (red) antibodies, and DAPI (blue). A, UAS-RasV12, UAS-RhoAN19 mutant clones. B, UAS-RasV12, UAS-RafK497M mutant clones. C, UAS-RasV12, UAS-Dsor1 RNAi mutant clones. D, UAS-RasV12, UAS-PI3KDN mutant clones. E, UAS-RasV12, Stat92Ej6C8 mutant clones. F, UAS-RasV12, Pka-C1B3 mutant clones. G, UAS-RasV12, TorΔP mutant clones. H, UAS-RafGof mutant clones. I, UAS-RhoAV14 mutant clones. Dashed arrows point from the ureter to the upper tubules. Scale bars represent 10 μm.

To check the effectiveness of RNAi of cyc E or dMyc in knocking down the corresponding geneṕs activity, we examined expression of dMyc and CycE in RNSC clones of RasV12 alone (Figure S3C and E) or RasV12 with RNAi of dMyc (Figure S3D) or RasV12 with RNAi of cyc E (Figure S3F). We once again observed that RNAi of cyc E or dMyc did not affect the RasV12 phenotypes although both RNAi of dMyc and RNAi of cyc E significantly blocked the corresponding protein overexpression associated with RasV12 mutation (compare Figure S3D with 3C and 3F with 3E), further suggesting that Ras either transforms RNSCs by a mechanism independent of dMyc and Cyc E or the residual activity of dMyc and Cyc E is still sufficient to mediate Ras function.

Finally, we expressed constitutively active Raf, RhoA, or ERK (rlSem) in RNSCs, using the PMML technique. We found that only the constitutively active Raf induced stem-cell tumor formation (Fig. 6H and I; data not shown), which is consistent with previous report that Raf was the primary effector of Ras in other Drosophila systems (Prober and Edgar, 2000).

In summary, the above results suggest that the MEK, RhoA, Tor, and PKA pathways function downstream of Ras/Raf in transforming RNSCs, and that Ras functions downstream of JAK-STAT, Scrib, and Sav. The activation of RhoA and MEK/ERK are necessary but not sufficient to induce RNSC tumor formation. The RNAi of cyc E or dMyc was insufficient to suppress the RasV12 phenotypes, suggesting that other downstream factors besides Cyc E and dMyc are critical for mediating Rasṕ function in RNSC transformation.

Discussion

There is now compelling evidence that most cancers are generated from cancer stem cells (CSCs) (Reya et al., 2001; Kim and Dirks, 2008). Drugs that specifically target CSCs could prove to be highly effective treatments for cancer. However, because CSCs often express markers of normal stem cells and remain dependent upon the niche microenvironments that regulate normal stem cells (Calabrese et al., 2007; Barker et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2009), anti-CSC drugs may also damage normal stem cells and possess significant toxicities. Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying how normal stem cells are transformed into CSCs and identifying the differences between normal stem cells and CSCs in different tissues are important prerequisites for developing anti-CSC therapeutic strategies.

In this study, we demonstrated that the mutation of tumor suppressors Scrib or Sav or activation of the oncogene Ras promotes stem-cell transformation in adult Drosophila MTs, and that Ras functions downstream or parallel of Scrib and Sav in the regulation of stem-cell transformation. The Ras-transformed stem cells exhibited many of the hallmarks of cancer, including increased proliferation, reduced cell death, and failure to differentiate. Downstream of Ras/Raf, several signal transduction pathways, including MEK/MAPK, RhoA, PKA, and TOR, cooperatively mediate Rasṕ function in regulating stem-cell transformation. These findings could be helpful for us to understand the stem cell transformation.

Function of the tumor suppressors Scrib and Sav in RNSC transformation

Our results showed that loss-of-function mutations of Scrib or Sav in MTs caused an increased proliferation of RNSCs. However, the RNSCs remained capable of differentiating into daughter cells, although the proportion of stem cells/differentiated cells and the mitotic index were higher in the mutant than in wild-type MTs. Similar phenotypes are reported for lethal giant larvae (lgl) mutant larval neuroblasts in Drosophila (Lee et al., 2006) and patched (ptc) mutant neural stem cells (NSCs) in the mouse (Yang et al., 2008). The sum of the evidence indicates that stem cells bearing mutant tumor-suppressor genes occasionally undergo ectopic self-renewal to generate two stem cell daughters. This may lead to early expansion of the stem-cell pool and, in turn, to a significant increase in direct downstream precursors, which continue to expand and ultimately contribute to tumorigenesis.

Relationship between the tumor suppressors Scrib/Sav and the Ras oncogene

The polarity regulator Scrib cooperates with a Ras gain-of function mutant (RasV12) to promote tumor progression and cell invasion in Drosophila imaginal tissues (Brumby and Richardson, 2003; Pagliarini and Xu, 2003). Scrib mutant clones in the eye disc exhibit loss of cell polarity, defective differentiation capacity and ectopic cell proliferation, but do not overgrow due to increased cell death, while RasV12 in the eye disc promote differentiation, cell survival and cell proliferation (Brumby and Richardson, 2003). When oncogenic Ras is expressed within the scrib mutant clones, the differentiation is attenuated, cell death is prevented and cell proliferation is further enhanced, these functions together promote neoplastic tumor development. However, our data suggest that Scrib acts upstream of Ras (because the lack of Ras prevented the Scrib mutant phenotypes) in regulating RNSC transformation, and the loss of Scrib did not further enhance the RasV12 mutant phenotype. The lacking cooperation of Scrib and Ras in RNSCs maybe due to the unique properties of RNSCs. In RNSCs, the scrib mutant clones did not exhibit increased cell death (data not shown) and the RasV12 did not promote differentiation (Figure 2B and C), therefore scrib− and RasV12 do not compensate each other in transforming RNSCs.

In Drosophila imaginal tissues, Sav is a tumor suppressor of a recently described Drosophila signaling pathway, the Hippo/Sav/Warts (Wts) pathway; Hippo and Wts are protein kinases, and Sav is a scaffold protein that helps activate their kinase activities (Saucedo and Edgar, 2007). Sav mutations have been found in human kidney cancer cell lines (Tapon et al., 2002). Activation of the Hippo pathway leads to cell-cycle arrest and/or apoptosis. The Hippo family kinases bind to members of the Ras association family (RASSF) in both mammalian and Drosophila cells (. Saucedo and Edgar, 2007; Polesello et al., 2006). Drosophila RASSF (dRASSF) restricts the tumor suppressor activity of Hippo (an oncogenic role) by competing with Sav for binding to Hippo (Polesello et al., 2006). However, the loss of dRASSF also partially rescues the Ras-loss phenotype (a tumor-suppressing role) in the developing eye (Polesello et al., 2006). Our data for RNSCs suggest that Sav, like Scrib, acts upstream of Ras. It will be interesting to determine whether dRASSF also bridges the interaction between Sav and Ras in the regulation of the RNSCs, in future studies.

Ras-transformed CSCs exhibit many of the hallmarks of cancer

In their advanced stages, human cancers exhibit several hallmarks (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2000), including supplying their own growth/proliferation signals, insensitivity to anti-proliferative signals, evasion of apoptosis, failure to differentiate, invasion/metastasis, activation of a telomerase to allow unlimited replicative potential, and increased angiogenesis. Only the first four hallmarks are conserved in the Drosophila model of cancer, because the fly uses a system different from mammalian telomere maintenance to control its DNA replication, and continued tumor growth does not depend on angiogenesis, because of the flyṕs open circulation system (Brumby and Richardson, 2005). However, the Ras-transformed RNSCs displayed the first three hallmarks, suggesting that they are like cancer stem cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Xie, I. Hariharan, D. Bilder, C. Doe, S. Campuzano, D. J. Pan, D. Kalderon, M. Stern, G. Halder, and the Bloomington and VDRC stock centers for fly stocks; and D. Stein, T. Uemura, B. Hay, H. Richardson, A. Wodarz, C. Doe, D. J. Pan, and the Developmental Study Hybridoma Bank for antibodies.

References

- Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amcheslavsky A, Jiang J, Ip YT. Tissue damage-induced intestinal stem cell division in Drosophila. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbacid M. ras genes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:779–827. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.004023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, Ridgway RA, van Es JH, van de Wetering M, Begthel H, van den Born M, Danenberg E, Clarke AR, Sansom OJ, Clevers H. Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature. 2009;457:608–611. doi: 10.1038/nature07602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder D, Li M, Perrimon N. Cooperative regulation of cell polarity and growth by Drosophila tumor suppressors. Science. 2000;289:113–116. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5476.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder D. Epithelial polarity and proliferation control: links from the Drosophila neoplastic tumor suppressors. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1909–1925. doi: 10.1101/gad.1211604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumby AM, Richardson HE. Using Drosophila Melanogaster to map human cancer pathways. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:626–639. doi: 10.1038/nrc1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumby AM, Richardson HE. scribble mutants cooperate with oncogenic Ras or Notch to cause neoplastic overgrowth in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2003;22:5769–5779. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchon N, Broderick NA, Poidevin M, Pradervand S, Lemaitre B. Drosophila intestinal response to bacterial infection: Activation of host defense and stem cell proliferation. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese C, Poppleton H, Kocak M, Hogg TL, Fuller C, Hamner B, Oh EY, Gaber MW, Finklestein D, Allen M, Frank A, Bayazitov IT, Zakharenko SS, Gajjar A, Davidoff A, Gilbertson RJ. A perivascular niche for brain tumor stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee M, Ip YT. Pathogenic stimulation of intestinal stem cell response in Drosophila. J Cell Physiol. 2009;220:664–671. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin SJ, Nehme NT, Limmer S, Liegeois S, Pospisilik JA, Schramek D, Leibbrandt A, Simoes RD, Gruber S, Puc U, Ebersberger I, Zoranovic T, Neely GG, von Haeseler A, Ferrandon D, Penninger JM. Genome-wide RNAi screen identifies genes involved in intestinal pathogenic bacterial infection. Science. 2009;325:340–343. doi: 10.1126/science.1173164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow LE, Elsum IA, King CL, Kinross KM, Richardson HE, Humbert PO. Loss of human Scribble cooperates with H-Ras to promote cell invasion through deregulation of MAPK signaling. Oncogene. 2008;27:5988–6001. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman-Scheel M, Weng L, Xin S, Du W. Hedgehog regulates cell growth and proliferation by inducing cyclin D and cyclin E. Nature. 2002;417:299–304. doi: 10.1038/417299a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C. Spindle orientation, asymmetric division and tumor suppression in Drosophila stem cells. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:462–472. doi: 10.1038/nrg2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey KF, Pfleger CM, Hariharan IK. The Drosophila Mst ortholog, hippo, restricts growth and cell proliferation and promote apoptosis. Cell. 2003;114:457–467. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00557-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou XS, Chou TB, Melnick MB, Perrimon N. The torso receptor tyrosine kinase activates raf in a Ras-independent pathway. Cell. 1995;81:63–71. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Patel PH, Kohlmaier A, Grenley MO, McEwen DG, Edgar BA. Cytokine/JAK/STAT signaling mediates regeneration and homeostasis in the Drosophila midgut. Cell. 2009;137:1343–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CF, Dirks PB. Cancer and stem cell biology: how tightly intertwined? Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirilly D, Spana EP, Perrimon N, Padgett RW, Xie T. BMP signaling is required for controlling somatic stem cell self-renewal in the Drosophila ovary. Dev Cell. 2005;9:651–662. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, Murdoch B, Hoang T, Caceres-Cortes J, Minden M, Paterson B, Caligiuri MA, Dick JE. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367:645–648. doi: 10.1038/367645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Robinson KJ, Doe CQ. Lgl, Pins, and aPKC regulate neuroblast self-renewal versus differentiation. Nature. 2006;439:594–598. doi: 10.1038/nature04299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 1999;22:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micchelli CA, Perrimon N. Evidence that stem cells reside in the adult Drosophila midgut epithelium. Nature. 2006;439:475–479. doi: 10.1038/nature04371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michor F, Hughes TP, Iwasa Y, Branford S, Shah NP, Sawyers CL, Nowak MA. Dynamics of chronic myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2005;435:1267–1270. doi: 10.1038/nature03669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumor growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007;445:106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature05372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlstein B, Spradling A. The adult Drosophila posterior midgut is maintained by pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2006;439:470–474. doi: 10.1038/nature04333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliarini RA, Xu T. A genetic screen in Drosophila for metastatic behavior. Science. 2003;302:1227–1231. doi: 10.1126/science.1088474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polesello C, Huelsmann S, Brown NH, Tapon N. The Drosophila RASSF homolog antagonize the Hippo pathway. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2459–2465. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prober DA, Edgar BA. Ras1 promotes cellular growth in the Drosophila wing. Cell. 2000;100:435–446. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80679-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugatcheva OM, Mamon LA. Genetic control of development of Malpighian tubules in Drosophila melanogaster. Russian J Dev Biol. 2003;34:269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Repasky G, Chenette EJ, Der CJ. Renewing the conspiracy theory debate: does Raf function alone to mediate Ras oncogenesis? Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, Biffoni M, Todaro M, Peschle C, De Maria R. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2007;445:111–115. doi: 10.1038/nature05384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo HD, Bergmann A, Gonen H, Ciechanover A, Steller H. Regulation of Drosophila IAP1 degradation and apoptosis by reaper and ubcD1. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:432–438. doi: 10.1038/ncb795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saucedo LJ, Edgar BA. Filling out the Hippo pathway. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:613–621. doi: 10.1038/nrm2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, Squire JA, Bayani J, Hide T, Henkelman RM, Cusimano MD, Dirks PB. Identification of human brain tumor initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SR, Liu W, Hou SX. The adult Drosophila Malpighian Tubules are maintained by multipotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sözen MA, Armstrong JD, Yang M, Kaiser K, Dow JA. Functional domains are specified to single-cell resolution in a Drosophila epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5207–5212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapon N, Harvey KF, Bell DW, Wahrer DC, Schiripo TA, Haber DA, Hariharan IK. salvador Promotes both cell cycle exit and apoptosis in Drosophila and is mutated in human cancer cell lines. Cell. 2002;110:467–78. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00824-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessing A, Eichelberg D. Malpighian tubules, rectal papillae and excretion. In: Ashburner A, Wright TRF, editors. The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila. Vol. 2c. Academic Press; London: 1978. pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Huang J, Dong J, Pan D. hippo encodes a Ste-20 family protein kinase that restricts cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis in conjunction with Salvador and warts. Cell. 2003;114:445–456. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00549-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZJ, Ellis T, Markant SL, Read TA, Kessler JD, Bourboulas M, Schüller U, Machold R, Fishell G, Rowitch DH, Wainwright BJ, Wechsler-Reya RJ. Medulloblastoma can be initiated by deletion of Patched in lineage-restricted progenitors or stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:135–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Gibson P, Currle DS, Tong Y, Richardson RJ, Bayazitov IT, Poppleton H, Zakharenko S, Ellison DW, Gilbertson RJ. Prominin 1 marks intestinal stem cells that are susceptible to neoplastic transformation. Nature. 2009;457:603–607. doi: 10.1038/nature07589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.