Abstract

Knowing some basic principles about medicines would help patients to understand drug therapy and to help and encourage them to use it well. These principles relate to the categories and names of drugs, their different uses, how they reach the site of action (absorption, distribution, fate), how they produce their effects, both beneficial and harmful, the time courses of drug actions, how the pattern and intensity of the effects of a drug depend on dose and timing, drug interactions, how drug effects are demonstrated and investigated and sources of information and their trustworthiness.

These basic principles are an essential part of health literacy and understanding them would enable individuals to comprehend better the information that they are likely to receive about medicines that they will take. Different populations need different types of education. For schoolchildren, the principles could fit into biology and domestic science teaching, starting in the later years of primary school or early in secondary school. A teaching package would also be needed for their teachers. For adults, web-based learning seems the most practical option. Web-based programmes could be supported by the NHS and professional bodies and through public libraries and local community health services. Specific groups for targeting could include young mothers and carers of chronically ill people. For retired people, one could envisage special programmes, perhaps in collaboration with the University of the Third Age. Conversations between patients and professionals would then become more effective and help shared decision making.

Introduction

To be able to choose appropriate drug therapy, and to use it effectively and safely, requires understanding of some basic general principles about medicinal products and their uses, and how to apply these principles in considering particular medications.

Few members of the general public are aware of these principles, and so they cannot think sensibly or coherently about drugs. They have to depend on what they hear from prescribers or allied professionals, or what they read or hear from other sources, the reliability of which they cannot judge. The huge gap between professionals and patients in understanding health and illness is the greatest barrier to shared decision making, which should be offered to all patients who want it. However, discussions about this fundamental problem in health care have focused on ‘informing’ patients and the public, and have not addressed the need to educate people and make them ‘health literate’. ‘Information’ cannot be used by people who lack adequate ‘information receptors’, i.e. the ability to assimilate and process the information to their advantage. The structure and brevity of consultations allow no systematic teaching of the underlying principles.

Principles

The principles about which the public need to be educated are listed in Box 1.

Box 1 The principles of drug therapy about which members of the public should be educated.

Categories and names of drugs

The different uses of drugs

How drugs reach the site of action (absorption, distribution, fate)

How drugs produce their effects, both beneficial and harmful

The time course of drug actions

How the pattern and intensity of the effects of a drug depend on dose and timing

Drug interactions

How drug effects are demonstrated and investigated

Sources of information and their trustworthiness

Categories and names of drugs

Drugs are not logically categorized [1]. Nevertheless, knowing, for example, that atenolol and propranolol are both β-adrenoceptor blockers (named after their pharmacological action) and that amoxicillin and co-amoxiclav both contain penicillin antibacterial drugs (named after the organism from which the first penicillins were obtained) can be of help.

The names of drugs can be complicated and sometimes hard to pronounce and remember. Resulting confusion can lead to medication errors. However, it is useful to know that drugs have brand names and non-proprietary names, that the latter are often more informative than the former, but that sometimes the former need to be used instead.

The different uses of drugs

Patients are not always aware of the reason for taking a medication, and it can be helpful to explain which of the following uses are relevant:

preventive – to prevent illness or harms to health or wellbeing (for example, prevention of infections, prevention of anaemia in pregnancy);

supportive – helping to maintain bodily function;

symptomatic – to relieve or attenuate symptoms;

curative – to cure a disease or condition;

diagnostic.

How drugs reach the site of action

Knowing how and in what form a drug enters and leaves the body involves knowing that drugs are absorbed, distributed and eliminated, and that these events determine the pattern of effects and time course of action of a medication.

How drugs produce their effects and the time course of drug actions

This includes knowing that the effects of a medication are determined by its actions on various organs and functions of the body, the time course of these actions and the context of its use, for example, what the person expects and believes about it. These effects vary from person to person and can rarely be accurately predicted for an individual. Careful explanation of this may usefully modify an individual's expectations.

Both prescribers and patients need to be well informed about the nature and timing (i) of the intended effects of the drug and (ii) of its possible harmful or inconvenient effects, to enable them to weigh the expected benefits against the possible disadvantages. Knowing the effects of not taking a medicine can be as important as knowing about its benefits.

The professional contributes more knowledge in weighing up the balance of benefits and harms, but in the end what is decisive is how the patient values each outcome, including its quality, intensity and duration, in striking the balance. The better the prescriber and the patient understand each other, the better the outcome.

Drug interactions

Knowing that drugs can interact with each other can help the patient understand the need to seek advice when other therapies are introduced.

How drug effects are demonstrated and investigated

It is important to stress that fair comparisons are essential [2]. This includes comparing the drug treatment with what happens without it, minimizing biases and estimating statistically the likely role of chance in reaching the results. Patients also need to understand that anecdotal experience is often evidentially weak.

Sources of information and their trustworthiness

Information about medicines is widespread on the internet and much of what is available is of poor quality. Patients can benefit from being pointed to reliable sources of information.

Treatment guidelines and recommendations

Guidelines, such as those published by the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), are largely based on evaluation of randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs). In addition cost-effectiveness is often also taken into account. Since RCTs are essentially comparisons of groups of people given different treatments, they predict only the average effect to be expected. This means that in some people the effect will be greater and in others less. Awareness of this will help patients understand that the outcome that they experience may not be the same as the average expectation. If the individual turns out to be much more or much less sensitive to the drug than average, the guideline may not apply.

Applying the principles

Applying the principles requires some knowledge of the disease or problem to be treated, and how and in what circumstances the drug can influence it [3]. Both positive and negative effects of the drug need to be considered, to be able to weigh the estimated benefit against the possible or likely harms from it. Benefits and harms will vary with the dosage, duration and temporal pattern of use of the drug, and these are aspects that deserve discussion between prescriber and patient.

How can we get there?

First we must distinguish between information and education: people without information receptors, i.e. who are not properly educated and cannot assimilate and process health information to their advantage, are at a disadvantage.

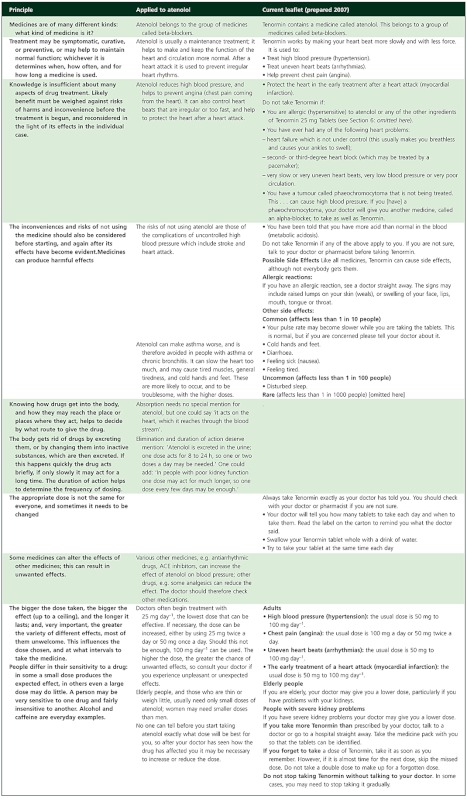

The simplest basic approach is to integrate the principles with the information, that is, to make them an inseparable part of Patient Information Leaflets (PILs) and perhaps of Summaries of Product Characteristics (SmPCs). That would facilitate fruitful discussions between patients and professionals, such as pharmacists, nurses and doctors. In 1995, after the European Directive on the contents of PILs had been translated into national regulations, I pointed out that they neither mentioned any of the principles nor supported good conversations between patients and professionals [4]. I suggested a revised version of the PIL for atenolol, in order to illustrate how one might incorporate the principles in it (Table 1). In designing PILs it is anyway high time to put the interests of patients and health professionals first. For instance, the overwhelming repetition of the brand name in PILs is obtrusive and absurd.

Table 1.

hebasic principles (column 1) applied to atenolol (column 2); column 3 gives the most nearly corresponding items in the current UK leaflet for atenolol 25 mg (Tenormin®) prepared by AstraZeneca in 2007; some parts of the text have been shortened (adapted from Herxheimer [4]])

Separate programmes to educate the public to understand and apply the principles require much more effort and resources, but we need to consider what methods are worth trying for different target groups.

For schoolchildren, the principles could fit into biology and domestic science teaching, starting in the later years of primary school or early in secondary school. A teaching package would also be needed for their teachers.

For adults, web-based learning seems the most practical option. Web-based programmes could be supported by the NHS and professional bodies and through public libraries and local community health services. Specific groups for targeting could include young mothers and carers of chronically ill people.

Since retired people could benefit disproportionately from better understanding of medicines, and have more time, one could envisage special programmes for them, perhaps in collaboration with the University of the Third Age (U3A) [5].

Although print and broadcast media also have an important role, frothy news appeal and editorial values can sometimes work against real understanding. In recent years, the work of the Science Media Centre has done much to improve this form of communication [6].

Conclusions

The public is woefully ignorant about medicines and their uses. Clinical pharmacologists and their allies can and should change this. A 5 year plan to this end is highly desirable.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aronson JK. Changing beta-blockers in heart failure: when is a class not a class? Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58:387–9. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X299317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans I, Thornton H, Chalmers I. Testing Treatments. 2nd edn. London: Pinter & Martin; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronson JK. Balanced prescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:629–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herxheimer A. Patient information leaflets: two serious omissions. Users of medicines need to understand more than PILs tell them. 1995. IUPHAR Newsletter. September: No. 45.

- 5.The Third Age Trust; U3A – The University of the Third Age. Available at http://www.u3a.org.uk (last accessed 12 January 2012)

- 6.The Science Media Centre. Available at http://www.sciencemediacentre.org/pages (last accessed 12 January 2012)