Abstract

Pharmacoeconomics is an essential component of health technology assessment and the appraisal of medicines for use by UK National Health Service (NHS) patients. As a comparatively young discipline, its methods continue to evolve. Priority research areas for development include methods for synthesizing indirect comparisons when head-to-head trials have not been performed, synthesizing qualitative evidence (for example, stakeholder views), addressing the limitations of the EQ-5D tool for assessing quality of life, including benefits not captured in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), ways of assessing valuation methods (for determining utility scores), extrapolation of costs and benefits beyond those observed in trials, early estimation of cost-effectiveness (including mechanism-based economic evaluation), methods for incorporating the impact of non-adherence and the role of behavioural economics in influencing patients and prescribers.

Introduction

Pharmacoeconomics is the discipline concerned with optimal allocation of resources to maximize population health from the use of medicines [1]. Given that resources for health care are finite, economic evaluation involves estimation of the opportunity cost, that is, the marginal benefits forgone as a result of displacing existing treatments or services to fund new medicines. Net health improvements result if the marginal benefits gained exceed the marginal benefits forgone.

The cost-effectiveness threshold is used by decision-makers, such as the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), the All Wales Medicines Strategy Group (AWMSG) and the Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) in the UK, to represent the marginal value of health. Medicines whose cost-effectiveness exceeds the threshold, conventionally set at £20 000 to £30 000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained, are less likely to be approved for use by the NHS [2].

Essential to every pharmacoeconomic evaluation is the need for quality evidence and robust methods. The regulatory requirements for the market authorization of medicines mean that evidential standards are high when compared with the majority of other health-care interventions, procedures and services. However, regulatory trials provide precise answers to questions about efficacy of treatments, as opposed to relative effectiveness. There are therefore several challenges and, as a comparatively young discipline, the methods of health economics continue being refined, particularly those to do with economic modelling, which is necessary for the determination of cost-effectiveness.

Here I shall review key priority areas for further research in pharmacoeconomics. I shall focus mainly on methodological research priorities associated with economic evaluation and appraisal of medicines, and draw on the findings of a scoping project commissioned by NICE and the Medical Research Council (MRC) [3]. However, in the parent discipline of economics, the potential application of behavioural economics is also discussed, this being part of the current coalition Government's ‘nudge’ policies to influence behaviour [4].

Evidence synthesis

Economic evaluations rely on data from disparate sources: clinical trials for efficacy, effectiveness, and harms, databases of routinely collected data for use of resources, costs, treatment patterns and harms, epidemiological data for incidence, prevalence and disease progression; expert opinion for treatment patterns and use of resources, patient surveys for health utilities and resource use and reference sources for unit costs and tariffs. Consequently, the information needs are greater than can be provided in a single clinical trial, and indeed, clinical trials alone are insufficient to meet the needs of those charged with making decisions about resource allocation [5]. Methods for robust evidence synthesis, including systematic reviews and meta-analyses, are therefore essential for reducing bias in economic evaluations. The following are priority areas.

Synthesizing indirect comparisons when head-to-head trials have not been performed

Clinical trials of new medicines rarely compare their performance against existing best practice. In the case of epilepsy, for instance, most trials, being industry-sponsored, are non-comparative, in order to meet the requirements of the regulatory authorities. As such, they are uninformative when selecting the most appropriate monotherapy for a typical patient with epilepsy [6]. Statistical methods for synthesizing head-to-head comparisons [7] require further refinement to account for bias, statistical and clinical heterogeneity, treatment combinations and sequential therapy.

Synthesizing qualitative evidence

Evidence from patients, patient organizations, medical experts, the lay public and pharmaceutical manufacturers about their experiences, value judgements and opinions are often not amenable to quantitative analysis, but are influential in cost-effectiveness decisions [8]. Methods for synthesizing these various forms of evidence and their incorporation into economic evaluations are under-researched, yet important areas for further development.

Measuring value

The prevailing metric of health outcomes in the context of health technology appraisals in the UK is the QALY, a measure that combines both quality and quantity of life into a single index to enable comparisons across different treatments and diseases. In constructing the QALY, times spent in states of health are valued on a scale of 0 to 1 (0 representing death, 1 representing optimum health) and are summed over an appropriate time horizon. However, many benefits are not captured adequately in QALY calculations. The following are priority areas.

Addressing the limitations of the EQ-5D

The EQ-5D is the preferred method that UK health technology appraisal organizations use for estimating the utility of treatments. It is a standardized instrument that asks questions in five dimensions of health: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression, each with three levels of intensity: no problems, some/moderate problems or severe problems. The sensitivity of the EQ-5D to changes in health is often questioned, but relatively poor sensitivity is unavoidable in a generic measure of health outcome. The validity of the EQ-5D has also been questioned, for instance in conditions associated with visual impairment [9] and hearing loss [10], in which treatments may consequently appear to be less cost-effective than they are. Alternative generic and condition-specific, preference-based utility measures (for example in asthma [11], overactive bladder [12] and epilepsy [13]) have been developed to address this limitation, but further research is warranted.

Valuation methods

EQ-5D health states are given a utility score according to value sets. These are based on large surveys of the public, using the time trade-off method, in which they are asked to imagine a particular health state and then state how many years they would be willing to sacrifice in order to be in full health. There is a need for assessing alternative methods of valuation, different populations (for example, patients vs. public), time of life (for example, at the end of life) and states that some perceive to be worse than death (which attract negative utility scores, which are difficult to deal with using conventional methods).

Measuring benefits not captured in QALYs

These include, for instance, baseline intensity of the condition, unmet need, and the effect on carers and the wider society. A debate about whether, to what extent and how these and other factors, such as innovation [14], should be quantified has already begun, partly in response to the proposal for a value-based pricing scheme for new medicines in the UK and the need to define ‘value’[15].

Methods of economic analysis

The requirement for modelling in economic evaluations has long been established [16]. However, there are many limitations: ‘all models are wrong; the practical question is how wrong they have to be to not be useful’[17]. Improvements in methods of modelling are continually being made, but there is still much to do. A good example of the limitations of modelling comes from the Mount Hood Challenge [18], in which models of diabetes mellitus were compared against one another in simulating a trial of type 2 diabetes (Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study), simulating a trial of type 1 diabetes (Diabetes Control and Complications Trial) and in calculating outcomes for a hypothetical, precisely specified patient (for cross-model validation). Not only did the results of models differ from one another significantly, but in some cases they varied significantly from the published trial data. The following are priority areas.

Extrapolation of costs and benefits beyond those observed in trials

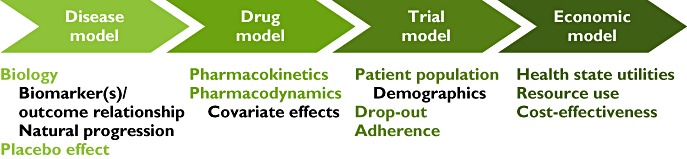

Economic evaluations must consider the full impact over time of an intervention on health outcomes and costs. An analysis based on the time horizon of short term clinical trials for chronic conditions would lead to biased estimates of cost-effectiveness. As an example, the disparate results of economic models of beta interferon and glatiramer acetate for the management of multiple sclerosis (ranging from about £40 000 to £400 000 per QALY gained) were largely explained by the time horizon adopted in each analysis [19]. Although a lifetime analytical horizon reduces bias, it introduces substantial uncertainty. Estimating treatment effects (and the associated effects on health-care costs) beyond the available data is clearly very challenging. However, health economists' reliance on empirical models rather than mechanistic models (in terms of drug action) is a serious limitation. There is much scope for the methods of quantitative pharmacology (namely, clinical trial simulations based on disease progression and population pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic models [20], [21]Figure 1) to be exploited in pharmacoeconomic evaluations.

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of the components of a mechanism-based economic evaluation

Early estimation of cost-effectiveness

Although pricing has always influenced decisions throughout drug development, the roles and methods of pharmacoeconomics are less well defined in the early phases [22]. It is far better for manufacturers to know sooner rather than later if the price needed to demonstrate cost-effectiveness (within a value-based pricing system) is not commercially viable. Again, models based on population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics may provide a useful approach for the early determination of cost-effectiveness [23], [24].

Impact of non-adherence

Despite the prevalence of non-adherence and early treatment discontinuation, few economic evaluations factor in the consequences of non-adherence on health outcomes and costs [25]. As pharmacoeconomics concerns the opportunity cost associated with the approval of new medicines, it is imperative that the effectiveness (not the efficacy) of a treatment be estimated. A highly efficacious intervention may have poor clinical effectiveness unless taken, and taken properly.

Behavioural economics

‘Nudging’ refers to influencing people's choices to promote healthier behaviours [26]. This might include, for instance, serving drinks in smaller glasses to reduce alcohol consumption, making stairs, not lifts, more prominent and attractive in public buildings to promote physical activity or incentivizing patients to abstain from substance misuse by issuing vouchers or payments. The following are priority areas.

Nudging patients

Financial incentives in the form of cash, vouchers, lottery tickets or gifts, to compensate individuals for the time, effort and cost involved in taking medicines, are associated with improvements in medication adherence [27]. Behavioural economics of adherence and other aspects of patients' use of medicines warrant further investigation [28].

Nudging prescribers

The Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) in the UK is a mechanism to nudge general practitioners (GPs) to provide better practice across four domains: clinical care, organization, patient experience and provision of additional services. Financial rewards for meeting targets have had the desired effect. In 2009/10 practices in England achieved an average of 937 points out of the maximum 1000 [29]. However, the effect of such schemes on health outcomes is more contentious. Although pay-for-performance has had no discernible effects on hypertension related clinical outcomes [30], an economic analysis of QOF payments has suggested that they are likely to be cost-effective, though only a small subset of indicators were considered [31]. Evidence from three Western European countries has suggested that prescribing incentives schemes can control drug costs and promote good prescribing practice [32]. Given the investment in the QOF (payments exceed £1 bn annually in England alone), further research is needed to ascertain whether nudging GPs really makes a difference.

Conclusion

Decision-makers face several challenges, not least because of recent austerity measures imposed on the National Health Service. Health-care funding has declined, and will continue to do so for years to come [33]. This will place an ever greater responsibility on prescribers to be conscious of costs and to apply the principles and methods of pharmacoeconomic evaluation. New policies, such as value-based pricing, whose introduction in the UK will coincide with the expiry of the existing Pharmaceutical Pricing Regulation Scheme (PPRS), will bring several methodological uncertainties that have yet to be assessed properly. As methods evolve, so too must the underpinning research. The priority areas outlined in this article are just a starting point.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hughes DA. From NCE to NICE: the role of pharmacoeconomics. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:317–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rawlins MD, Culyer AJ. National Institute for Clinical Excellence and its value judgments. BMJ. 2004;329:224–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7459.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Longworth L, Sculpher MJ, Bojke L, Tosh JC. Bridging the gap between methods research and the needs of policy makers: a review of the research priorities of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27:180–7. doi: 10.1017/S0266462311000043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dolan P, Hallsworth M, Halpern D, King D, Vlaev I. Mindspace: influencing behaviour through public policy. 2010. Institute for Government and the Cabinet Office (Discussion document) Available at http://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/MINDSPACE.pdf (last accessed 16 March 2012)

- 5.Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Drummond M, McCabe C. Whither trial-based economic evaluation for health care decision making? Health Econ. 2006;15:677–87. doi: 10.1002/hec.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chadwick D, Shukralla A, Marson T. Comparing drug treatments in epilepsy. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2009;2:181–7. doi: 10.1177/1756285609102327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ades AE, Claxton K, Sculpher M. Evidence synthesis, parameter correlation and probabilistic sensitivity analysis. Health Econ. 2006;15:373–81. doi: 10.1002/hec.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rawlins M, Barnett D, Stevens A. Pharmacoeconomics: NICE's approach to decision-making. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:346–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03589.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Espallargues M, Czoski-Murray C, Bansback N, Carlton J, Lewis G, Hughes L, Brand C, Brazier J. The impact of age related macular degeneration on health state utility values. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4016–23. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barton GR, Bankart J, Davis AC, Summerfield QA. Comparing utility scores before and after hearing-aid provision. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2004;3:103–5. doi: 10.2165/00148365-200403020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Y, Brazier JE, Tsuchiya A, Young TA. Estimating a preference-based index for a 5-dimensional health state classification for asthma derived from the asthma quality of life questionnaire. Med Decis Making. 2011;31:281–91. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10379646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Y, Brazier JE, Tsuchyia A, Coyne K. Estimating a preference-based single index from the Overactive Bladder questionnaire. Value Health. 2009;12:159–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulhern B, Rowen D, Brazier J, Jacoby A, Marson T, Snape D, Hughes D, Latimer N, Baker GA. Developing a health state classification system from NEWQOL for epilepsy using classical psychometric techniques and Rasch analysis: a technical report. Available at http://www.sheffield.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.43131!/file/HEDS-DP-10-16.pdf (last accessed 16 March 2012)

- 14.Ferner RE, Hughes DA, Aronson JK. NICE and new: appraising innovation. BMJ. 2010;340:b5493. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes DA. Value-based pricing: incentive for innovation or zero net benefit? Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29:731–5. doi: 10.2165/11592570-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buxton MJ, Drummond MF, Van Hout BA, Prince RL, Sheldon TA, Szucs T, Vray M. Modelling in economic evaluation: an unavoidable fact of life. Health Econ. 1997;6:217–27. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(199705)6:3<217::aid-hec267>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Box GEP, Draper NR. Empirical Model-Building and Response Surfaces. New York: Wiley; 1987. p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mount Hood 4 Modeling Group. Computer modeling of diabetes and its complications: a report on the Fourth Mount Hood Challenge Meeting. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1638–46. doi: 10.2337/dc07-9919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chilcott J, McCabe C, Tappenden P, O'Hagan A, Cooper NJ, Abrams K, Claxton K, Miller DH Cost Effectiveness of Multiple Sclerosis Therapies Study Group. Modelling the cost effectiveness of interferon beta and glatiramer acetate in the management of multiple sclerosis. Commentary: evaluating disease modifying treatments in multiple sclerosis. BMJ. 2003;326:522. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7388.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan PLS, Holford NHG. Drug treatment effects on disease progression. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:625–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holford N, Ma SC, Ploeger BA. Clinical trial simulation: a review. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:166–82. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartz S, John J. Contribution of economic evaluation to decision making in early phases of product development: a methodological and empirical review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2008;24:465–72. doi: 10.1017/S0266462308080616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes DA, Walley T. Economic evaluations during early (phase II) drug development: a role for clinical trial simulations? Pharmacoeconomics. 2001;19:1069–77. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200119110-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pink J, Lane S, Hughes DA. Mechanism-based approach to the economic evaluation of pharmaceuticals: pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic–pharmacoeconomic analysis of rituximab for follicular lymphoma. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30:1–17. doi: 10.2165/11591540-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hughes D, Cowell W, Koncz T, Cramer J International Society for Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research Economics of Medication Compliance Working Group. Methods for integrating medication compliance and persistence in pharmacoeconomic evaluations. Value Health. 2007;10:498–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marteau TM, Ogilvie D, Roland M, Suhrcke M, Kelly MP. Judging nudging: can nudging improve population health? BMJ. 2011;342:d228. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guiffrida A, Torgerson DJ. Should we pay the patient? Review of financial incentives to enhance patient compliance. BMJ. 1997;315:703–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7110.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elliott RA, Shinogle JA, Peele P, Bhosle M, Hughes DA. Understanding medication compliance and persistence from an economics perspective. Value Health. 2008;11:600–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NHS Information Centre, Prescribing and Primary Care Services. Quality and Outcomes Framework Achievement Data 2009/10. 2010. Available at http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/QOF/2009-10/QOF_Achievement_Prevalence_Bulletin_2009-10_v1.0.pdf (last accessed 16 March 2012)

- 30.Serumaga B, Ross-Degnan D, Avery AJ, Elliott RA, Majumdar SR, Zhang F, Soumerai SB. Effect of pay for performance on the management and outcomes of hypertension in the United Kingdom: interrupted time series study. BMJ. 2011;342:d108. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker S, Mason AR, Claxton K, Cookson R, Fenwick E, Fleetcroft R, Sculpher M. Value for money and the Quality and Outcomes Framework in primary care in the UK NHS. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60:e213–20. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X501859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sturm H, Austvoll-Dahlgren A, Aaserud M, Oxman AD, Ramsay C, Vernby A, Kösters JP. Pharmaceutical policies: effects of financial incentives for prescribers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006731. CD006731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Appleby J. What's happening to NHS spending across the UK? BMJ. 2011;342:d2982. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]