Abstract

Reduction of the duration of postpartum hospital stay in western countries highlights the need for better support and continuity of care for expectant and new mothers. The aim of this study was to investigate strategies to improve continuity of care for expectant and new mothers. The study also aimed to elaborate on a preliminary substantive grounded theory model of “linkage in the chain of care” that had been developed earlier. Grounded theory methodology, which involved multiple data sources comprising structured interviews with midwives and child healthcare nurses (n=20), as well as mothers (n=21), participant observation, and written material, was used. Comparative analysis was used to analyse the data. To achieve continuity, three main strategies, transfer, establishing and maintaining a relation, and adjustment, were identified. These strategies for continuity formed the basis of the core category, joint action. In all the strategies for continuity, midwives and child healthcare nurses worked together. In addition, mothers benefited from the joint action and recognized continuity of care when strategies for continuity were implemented. The results are discussed in relation to the established concepts of continuity.

Keywords: Continuity, collaboration, midwives, child healthcare nurses, expectant and new mothers, grounded theory

Continuity of care for expectant and new mothers requires attention because of the dramatic decrease in the duration of postpartum hospital stay in western countries. Integrated or collaborative care services have been proposed earlier (Schmied et al., 2010), but there is limited evidence that such strategies can improve continuity of care. In addition, health care professionals may experience collaborative strategies as an extra burden (D’Amour, Ferrada-Videla, San Martin Rodriguez, & Beaulieu, 2005).

Continuity of care is important for all mothers, especially those with special needs, such as postpartum depression (Rubertsson, Wickberg, Gustavsson, & Rådestad, 2005). Lack of continuity between antenatal care (AC) and child health care (CHC) has been attributed to different management structures, lack of interprofessional understanding, and disagreements with regard to professional boundaries (Homer et al., 2009).

In Sweden, AC and CHC are services organized separately, each with their own management (Barimani & Hylander, 2008). These services have an attendance of nearly 100% and are offered to all pregnant women and families with children aged 0–5 years (Sundelin & Håkansson, 2000). The primary caregivers in AC are certified nurses or midwives, whereas in CHC they are pediatric nurses or primary healthcare nurses (CHC nurses). As a consequence, successful strategies to achieve continuity must involve both midwives and CHC nurses.

The concept of continuity of care is defined and used differently in different contexts. Haggerty et al. (2003) reviewed literature from different fields and concluded that “continuity is the degree to which a series of discrete health care events is experienced as coherent, connected and consistent with the patient medical needs and personal context.” However, experiences of coherence, connection, and consistency may differ between the patient and the caregiver (Haggerty et al., 2003). Consequently, processes that are designed to improve continuity do not necessarily equate to continuity. Thus, the perspectives of both the patient and the caregiver must be analyzed.

Strategies for continuity of care include, but do not equate to, collaborative strategies between health care professionals and between healthcare units. The rationale for collaboration between units is that it fosters an advantage that could not have been achieved otherwise. In practice, however, collaborative strategies may have negligible effects and a slow output and may be viewed as a burden; these combined effects have been termed collaborative inertia (Huxham & Vangen, 2004). Collaboration as a concept has many dimensions, and professional collaboration can be seen at different levels both within and between units (Axelsson & Axelsson, 2006).

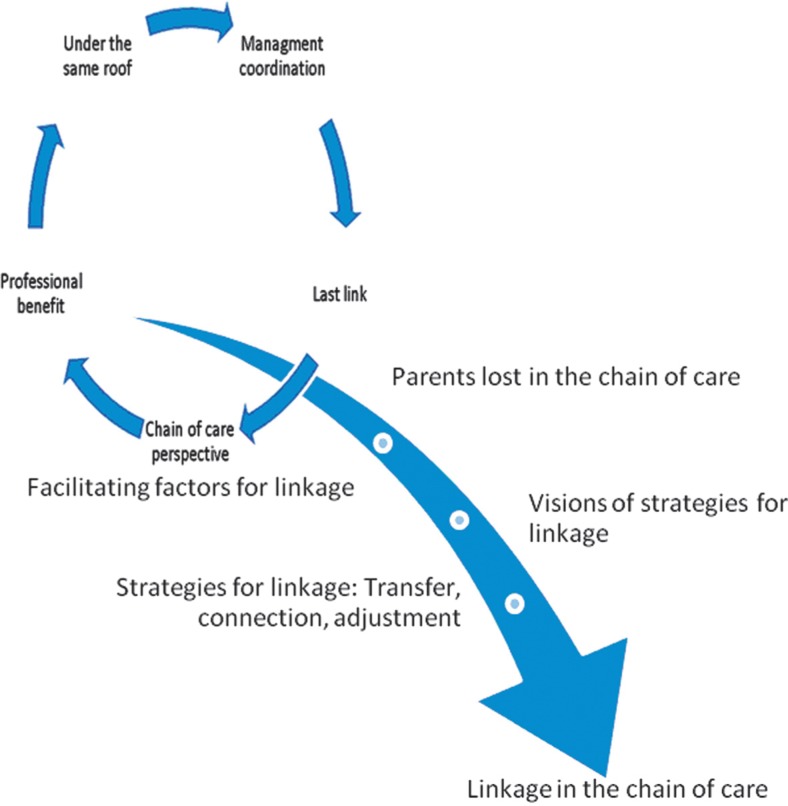

Barimani and Hylander (2008) saw continuity of care for expectant and new mothers as “linkage in a chain of care” between professionals across three components: AC, intrapartum/postpartum care (PC), and CHC. The proposed theoretical model presented in our earlier study (Barimani & Hylander, 2008) yielded a hypothesis as to why linkage in the chain of care is not achieved, in spite of well-known strategies and a common understanding of the importance of such linkage. Three potential strategies for linkage were identified: (1) transfer of information or problematic cases, (2) connection (joint activities), and (3) adjustment, aimed at achieving consensus. However, these strategies were not implemented, but only talked about and envisioned, by the midwives and CHC nurses in the study, partly owing to a lack of a perceived professional benefit. Despite the fact that the midwives and CHC nurses recognized that parents were lost in the chain of care but benefited from continuity in the chain of care, and although they had a common vision regarding strategies to achieve continuity, they reported that linkage was still not achieved. A link perspective, in which midwives and CHC nurses prioritized their own workplace, was recognized as a barrier to linkage. By contrast, a chain of care perspective, in which reasoning is based on knowledge of the entire chain of care, was seen as a facilitator . Link position was also important for linkage; CHC nurses in the last link benefited the most as they could depend on information from AC about mothers to come, whereas midwives in the first link, AC, saw strategies for linkage as an extra burden. Other factors that were found to facilitate the development of strategies for continuity were the presence of AC and CHC under the same roof and coordination of management (Barimani & Hylander, 2008) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Linkage in the chain of care.

The aim of this study was to investigate strategies for continuity of care for expectant and new mothers, as experienced by both midwives/CHC nurses and mothers. The study also aimed to elaborate on the preliminary substantive grounded theory model of “linkage in the chain of care.”

Method

A theory-generating approach (Bryant, 2007; Charmaz, 2006; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Guvå & Hylander, 2003; Hallberg, 2006) was applied to elaborate on the preliminary grounded theory model. The grounded theory method (GTM) used in this study is influenced by classic GTM with regard to emphasis on conceptualization. However, in contrast to classic GTM, we regard the model that results from this study to be a construction of the researchers (Charmaz, 2006; Guvå & Hylander, 2003) and certainly recognize its roots in symbolic interactionism (Blumer, 1969). The present approach of GTM aims at combining conceptualization from a substantive area with established theories in the field. The guidelines followed were first published in 2003 (Hylander, 2003) and have since been used in several studies. For recent examples of this approach, see Alizadeh, Hylander, Kocturk, and Törnkvist (2010) and Barimani and Hylander (2008).

Theoretical sampling procedure

Given that the present study is part of a larger project, in which a preliminary model had already been constructed (Barimani & Hylander, 2008), the collection of data was more selective, and interviews were more focused, than during the first stage of open coding in accordance with the GTM. The sample for the present study is a theoretical one, which was selected on the basis of information gained from the original open sampling procedure (Barimani & Hylander, 2008). Given that, in the earlier study, strategies for linkage were only talked about as visions, we wanted to study CHC nurses and midwives who actively implemented strategies to achieve continuity. Thus, a theoretical sample of midwives and CHC nurses at two workplaces where AC and CHC services were located in the same building was selected. In the first workplace, “the family center,” midwives and CHC nurses worked together as an integrated team, and in the second case, “the medical center,” the management had expressed clear intentions for collaboration between AC and CHC services. We limited our focus on strategies used by CHC nurses and midwives because they are the primary caregivers in the chain of care for expectant and new mothers in Sweden.

As the preliminary model was constructed on the basis of caregiver interviews, we wanted to study the concept of continuity from the perspectives of both the caregiver and the patient.

The emerging theory and information gained in the present substudy guided the sampling process and determined the number of interviews needed for saturation. In the family center, all CHC nurses (3) and midwives (2) were interviewed. In the medical center, 14 out of 20 CHC nurses and all midwives (7) were interviewed. At both the centers, during different time points, mothers at the CHC waiting room with a child less than 6 months old were invited to participate in the study. When it became apparent that the middle management in the medical center expressed visions about implementing strategies for continuity, observational data from meetings were included. In the family center, where joint actions were observed, common protocols and written strategies were collected. Two interviews were carried out with a CHC nurse and a midwife in the medical center, a year later, after it was discovered that the strategies discussed had not been realized. They were asked whether there had been or was a plan to implement the strategies envisioned and if not, why it was so.

Data were, thus, collected from interviews, participant observations, and documents (Table I). The interview guide for midwives and CHC nurses included questions about collaboration between midwives in AC and nurses in CHC and their perception of mothers’ experience of such collaboration. The interview guide for mothers included questions about their perceptions of support and continuity, for example, from whom they obtained support before and after childbirth, whether they had experienced collaboration between AC midwives and CHC nurses, and whether they knew whom to turn to in case they ran into problems. The interviews were recorded and verbatim transcribed. Participant and low-structured observations were made at meetings, in the waiting room, and during joint activities that involved both AC and CHC, and these observation protocols complemented the interviews (Bryman, 2008). Field notes were taken during and immediately after low-structured observations, and a research diary was kept. Local documents on strategies for continuity, which were read and used by the midwives and CHC nurses, were used as informational material. Data were collected by the first author (M.B.) over a period of 1 year (2008–2009).

Table I.

Data sources.

| Data sources | Family center | Medical center |

|---|---|---|

| Interviews: Midwives, CHC nurses (15–40 min) (N=20) | n=5 (2 midwives, 3 CHC nurses) | n=15 (7 midwives, 8 CHC nurses) |

| Interviews: Mothers (15–40 min) (N=21) | n=11 (2 first-time mothers, 9 mothers with more than one child) | n =10 (5 first-time mothers, 5 mothers with more than one child) |

| Participant observation (40 h); low-structured observations | Waiting room, team meetings, home visits | Waiting room, meetings |

| Documents | Annual reports | Meeting protocol |

Data analysis

Qualitative methods used in this study were complemented by a quantitative analysis. This approach has been proposed in grounded theory, although it is not often used (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser, 1978). The interviews and observations with AC midwives, CHC nurses, and expectant and new mothers were coded line-by-line by constant comparison to elaborate on the strategies for continuity. New codes and subcategories were constructed. The main categories from the preliminary model also earned a place in the present data set, and by adding new subcategories, the meaning of the main categories was further altered into more elaborate concepts, leading to a new main category being added and a new core process being discovered. The first author (M.B.) conducted the line-by-line coding. The two authors (M.B. and I.H.) processed the subsequent analyses cooperatively and attempted to reach a consensus. The discovery of a major difference in the implementation of strategies for continuity of care between the two workplaces led to the question of whether patient benefits also differed between the two workplaces. For this reason, a quantitative comparison of mothers’ experiences of support and continuity of care between the two workplaces was performed. Patient benefits was quantified by coding mothers’ experiences of support (overall support, breastfeeding support, mothers’ recommendations for support) and their perception of continuity of care (perception of collaboration between AC and CHC, experience of meeting staff from AC and CHC before and after delivery, and whether they knew where to turn to for help or not). The answers were coded as YES or NO, and Fisher’s exact test was used to detect possible differences between the samples.

Ethical considerations

The regional ethics committee in Stockholm approved the study (2008/1241-31/3). All participants were given written and verbal information about the aim of the study, processes followed, and their right to withdraw from the study at any time.

Results

Joint action—Acting together for continuity of care

The main concern of the interviewed CHC nurses and midwives was to ensure that mothers benefited and experienced support and continuity, which was also consistent with mothers’ expectations. However, some nurses and midwives only had visions of strategies for continuity of care, whereas others actually implemented strategies for continuity. While the staff at the family center described how they used these strategies, those at the medical center described their visions for strategies without them being realized. When strategies for continuity of care were implemented, the CHC nurses and midwives acted together in joint activities (between CHC nurses and midwives) or in joint support (CHC nurses, midwives, and mothers) through several different joint practices guided by the three strategies for continuity, transfer, adjustment, and establishing and maintaining a relation.

Thus, compared to the preliminary model of linkage in the chain of care, connection evolved into the core category of joint action. In addition, a new strategy for continuity of care, establishing and maintaining a relation, emerged (Table II).

Table II.

The core process of joint action.

| Core | Sub cores | Main categories with sub categories | Relation between modes/strategies and practices |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modes of joint action | Joint activities |

|

|

| Joint support | |||

| Joint action | Strategies of joint action | Transfer of information

|

|

Establishing and maintaining a relationship

|

|

||

Adjustment

|

|

||

| Practices of joint action | Informal and formal meetings, Joint policy documents Introduction of new employees Joint home visits, Joint parent education classes Joint breastfeeding support Knocking on the door |

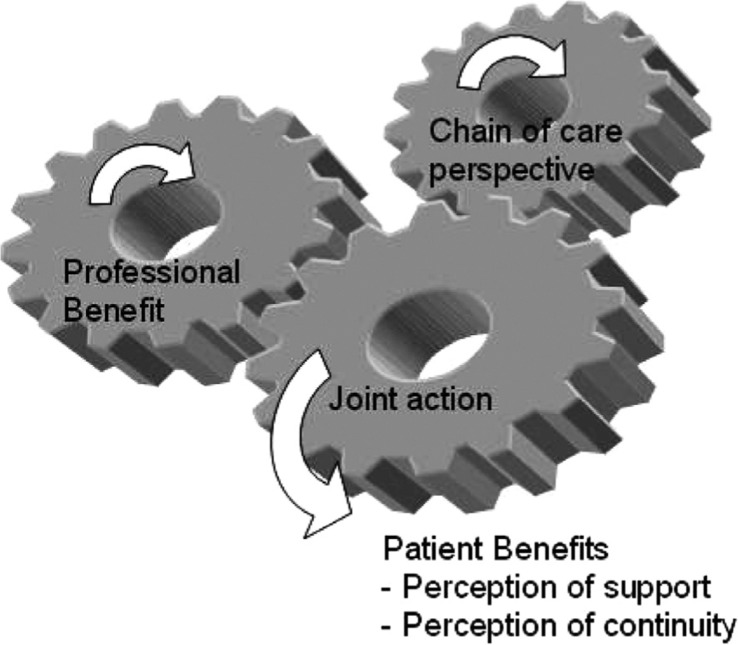

A chain of care perspective and professional benefit facilitated joint action, but paradoxically joint action also seemed to be a prerequisite for the experience of professional benefit and a chain of care perspective. Thus, joint action seems to be the central cog that enables everything else to function effectively. Joint action is an important trigger for professional benefit and a chain of care perspective, but these two factors may not be sufficient to initiate joint action, they can only maintain it. Also, joint action had the expected effect on mothers’ perceived support and continuity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The core category of joint action.

A chain of care perspective versus a link perspective

The two workplaces could be described in terms of a chain of care perspective, i.e., when midwives and CHC nurses based their reasoning on knowledge of the entire chain of care, versus a link perspective, i.e., when midwives and CHC nurses prioritized their workplace.

A chain of care perspective. The midwives and CHC nurses at the family center expressed a clear chain of care perspective. Being close to and having opportunities to communicate with other links in the chain facilitated a chain of care perspective. A chain of care perspective included being knowledgeable about other links in the chain and envisioning patient benefits.

The midwives and CHC nurses said that they started to collaborate when they realized that they worked with the same mothers and supported the notion of “parenthood starts with pregnancy and continues after childbirth.” The midwives stated that a good transfer procedure made it possible for the CHC nurses to take over from where the midwives left off, and this was important because if the mother did not feel well it would affect attachment to her child.

This small and integrated group described themselves as “one unit,” not AC and CHC, but a “team.” They had provided integrative services to parents and their children in a typical immigrant neighborhood for 10 years. The AC and CHC services are located on the same floor, and there is a shared lunchroom in the center of the building.

The midwives and CHC nurses considered being knowledgeable about each other’s work to be important. Given that they could “say the same thing from different professions,” as one CHC nurse explained, the CHC nurses could remind mothers of subjects discussed with their midwives during pregnancy.

The midwives and CHC nurses also emphasized the patient benefit of strategies for continuity, believing that parents benefited from knowing that the AC and CHC formed a unit. This was supported by interviews with mothers, who said that it felt as though one person knew what the other person was doing. Thus, mothers recognized the chain of care perspective and said, “It is obvious that they are connected and collaborate. I saw that when I was expecting and now when I visit the CHC” and “Striving forwards together!”.

A link perspective. We found several clear examples of link perspectives in which midwives and CHC nurses prioritized their own facility, in the medical center. This is a newly opened center adjacent to pediatric services in an upper middle class neighborhood. The AC and CHC services were located in the same building but on different floors. A lunchroom located on the same floor as CHC, which was supposed to be shared with AC, was used only by CHC a year later.

There was lack of knowledge about the competence of AC at CHC and vice versa. One CHC nurse, when asked about collaboration with midwives in breastfeeding support, stated that “I don’t know what to say, I honestly don’t know the competency of those midwives, that’s how bad it is.”

Mothers were aware of the lack of collaboration between AC and CHC and thought that the midwives and CHC nurses worked in isolation, even though they worked in the same building. They expressed it as “a sharp dividing line,” “a distinct division,” and “a gap.” Mothers also desired more collaboration, as indicated by statements such as, “Perhaps they should work more together; I haven’t seen that.”

Strategies for continuity through joint action

At the family center, the midwives and CHC nurses worked together through joint actions to establish continuity of care for expectant and new mothers. Joint actions were seen as joint activities between the CHC nurses and midwives (socializing, meeting, and interacting) and joint support toward mothers. Thus, they did things together both with and without parents. A bulletin board that displayed their work schedules and telephone numbers served as a means of coordinating joint activities. The development of clear strategies for joint actions, such as informal ways of making decisions and helping each other actively during times of heavy workload, were also mentioned. Three different strategies for continuity through joint action, transfer of information, adjustment, and establishing and maintaining an ante- and postnatal relationship, were seen.

The transfer of information included the transfer of general information about all women and specific information about women in need of special support.

We found that transfer of general information occurred during formal and informal meetings. The staff had formal meetings to find out the mothers who were expected to give birth in the following month so that they could plan home visits and prioritize the newborns. Sharing a lunchroom was important for informal interaction, and breaks were used for discussing work, as it was often the only time they could meet. One midwife said,

“At coffee breaks, it’s OK to talk about work, it might be the only time during the day when we can plan things. We make use of each minute! Then we have fun too! Not just work.”

Transfer of specific information about mothers was conducted as joint support. Joint home visits and introducing mothers by “knocking on the door” of the CHC nurses’ office were ways of transferring specific information. These approaches enabled mothers to be involved and to have the opportunity to recount their stories. The midwife and CHC nurse made a joint home visit to all new mothers soon after they had been discharged from the hospital. This enabled mothers to transfer information to the CHC nurse in person, with the support of the midwife. An excerpt based on observation notes that describe the hand-over process between a midwife and a CHC nurse during a joint home visit is as follows:

Mother opens the door and gives her midwife a big hug, before saying hello to the CHC nurse, and then puts the baby in the arms of the midwife. The midwife asks about her birth experience and the mother talks about it, focusing on the midwife. After a while the midwife asks if she has met the CHC nurse. “No,” she says and shows the reports about the child to her. The midwife says, “You have been seeing me, but from now on the CHC will take over.” She also says that the child seems content. “Does she sleep at night?” Now they start talking about breastfeeding and the CHC nurse joins in.

One mother expressed satisfaction with the home visits by saying, “It was wonderful when AC and CHC staff came on a home visit; they came together so I did not have to get to know an entirely new person.” Mothers who were in need of special support were introduced to the CHC routinely during pregnancy because the midwives and the CHC nurses said that mothers would feel more secure if they could discuss openly what they had been through and if they knew that the CHC nurse was familiar with their case. Given that the CHC and AC were located on the same floor, it was easy to “knock on the door” and transfer information with the mother present, as noted by one CHC nurse:

The best thing is that we are under the same roof. I can walk into the room of the midwife if I haven’t got all the information I need. I can knock on the door right away, which makes it easier. They bring in mothers to us as well, so they know who they are going to meet afterwards.

Also, mothers recognized that having the AC and the CHC services on the same floor facilitated information transfer,

“The staff seems to know each other, and then it becomes natural to collaborate. When I had a question, my CHC nurse knocked on the door of the midwife and forwarded the question, they seem to collaborate nicely.”

The CHC nurses and midwives established ante- and postnatal relationships with mothers by joint support. An antenatal relationship was established during pregnancy by the midwife introducing the CHC nurse to mothers with special needs by “knocking on the door” and through joint parental education classes.

The relationship with the midwife was maintained after birth through home visits (as already described) or breastfeeding support. All mothers had the opportunity to be introduced to their CHC nurse during pregnancy through joint parental education classes. The midwives held parental education classes during pregnancy, and the CHC nurses took over the classes or joined in in the final month of pregnancy.

Adjustment means sharing the same policy agreements and patient information to approach consensus (joint policies) and for midwives and CHC nurses to learn from each other (joint learning). The midwives and CHC nurses tried to achieve coordination on policy issues to promote joint policies and joint learning. This was particularly pronounced with regard to breastfeeding support, because they said, “that is where our professions meet.” A breastfeeding telephone support line was open between 9 am and 3 pm, and the midwives and CHC nurses took turns in answering the telephone. When mothers wanted to visit the clinic for a breastfeeding consultation, they usually came to CHC, but they could also meet a midwife from AC.

The CHC nurses and midwives engaged in joint learning and consulted each other when they needed more information, “We often discuss when there is a case of a breastfeeding problem. I may see a woman but feel that I need to consult a midwife.”

Joint policies were activated in relation to breastfeeding support. Annual work reports were written jointly by the CHC nurses and midwives and served as an introduction for new staff, which also promoted a joint policy. Thus, they could say “the same things from the perspective of our professional disciplines, and that’s our strength.” To maintain a common policy, new employees were typically introduced to the objectives of the general policy at the family center, and the staff of the family center was involved when new employees were interviewed. Mothers also expressed appreciation of the joint breastfeeding support and policy.

Visions of strategies for continuity, but no joint action

This study showed that mere visions of strategies for continuity were not enough to establish joint actions. In the medical center, the management had a clear vision of the new strategies for continuity that could result from the geographical integration, and this vision was expressed during the monthly “house meetings” that most staff attended, as noted in the observation and meeting protocols. In practice, however, joint actions were not performed, “Before we moved in we had a meeting and we had great plans but it came to nothing.”

There were visions of joint actions, but these visions never turned into practice. Visions of joint activities, such as shared lectures and joint after-work parties to get to know each other, and joint support with parental education classes were expressed but not realized. Some CHC nurses referred parents to external clinics for support rather than engaging in joint support for breastfeeding.

CHC nurses not only had visions of transferring knowledge by “knocking on each other’s door” in order to get specific information about mothers with special needs but also establishing and maintaining a relationship with these mothers, as one CHC nurse expressed that “There was no information. They (AC) could have come with a note saying that you need to see this mother in a hurry. Too bad when we are in the same building.”

There were also visions of adjustment in order to have the same policy for breastfeeding support, but in practice, there were no common protocols of goals or objectives for AC and CHC. Neither were there signs of joint learning although the need for such learning was expressed that “I get many questions, particularly from mothers with a caesarean section, what does the scar look like? That is not my field!”

Mothers stated that they wanted more joint support from AC and CHC in parental education classes. They expressed a lack of establishing and maintaining a relationship because they had not met with the midwife after childbirth; they felt “cut off” from AC and wanted a follow-up visit from the midwife to achieve closure and continuity. Also, mothers opined that they did not know where to turn to when they ran into problems with breastfeeding.

In summary, having a vision is not enough. Even though the midwives and CHC nurses worked in the same building and wanted to collaborate, no joint actions were performed. The initial vision of collaboration between the midwives and CHC nurses had not been realized. A year after the AC and CHC services moved into the same building, one of the interviewees said that collaboration “collapsed like a house of cards.” There are several possible reasons why continuity was never achieved at the medical center, and these have been discussed later. By contrast, the staff at the family center said that time constrains meant that collaborative strategies were necessary and that joint actions were prioritized over visions and planning. As one CHC nurse said:

I think one should “do” instead of talk about doing!! There is time to talk when we make the home visits together, the same goes with parental education groups; we don’t have time for much planning, we just do it!

Professional benefit

When implemented, the strategies for continuity were seen as beneficial to professionals, rather than a burden to them. Saving time, meaningfulness, interprofessional learning, and mere pleasure were described as professional benefits. One midwife even thought that she may have selfish reasons for wanting to make home visits after childbirth as she thought this was “such a good way to finish off pregnancy.” Both midwives and CHC nurses described the professional benefit of joint parental education. For the midwives, continuity strategies were helpful when they were running short of time, and for the CHC nurses, they made running parental education classes easier as the parents already knew each other when they came to the classes after their child was born.

Patient benefits – Mothers’ experience of continuity and support

Mothers agreed on the benefits of joint actions through all three strategies for continuity. They appreciated the fact that one person knew what the other was doing and they “were striving forwards together.” One mother expressed “how entirely wonderful” it was when the midwife and the CHC nurse made a joint home visit. They also said that they benefited from establishing and maintaining an ante- and postnatal relationship and that it was good to meet the CHC nurse even during pregnancy.

I participated in parental education classes with one representative from AC and one from CHC. And then I met the same CHC nurse after childbirth … that was great; even if you were focused on pregnancy, it was good to see the CHC nurse and establish contact with her.

When we discovered the difference between the two workplaces with respect to the professional strategies for continuity, we realized that it would be possible to systematically explore whether mothers also experienced this difference. Mothers’ experiences of support and continuity from the two workplaces support the findings from the qualitative analyses of the interviews with AC and CHC professionals. In the family centre, in which CHC nurses and midwives described the implementation of strategies for continuity, mothers expressed a greater experience of continuity of care than did mothers attending the medical centre. Nine out of eleven mothers at the family centre experienced collaboration between AC and CHC, while no mother at the medical centre perceived such collaboration (p<0,001). In addition, mothers attending the family centre experienced slightly better support than did mothers attending the medical centre (p<0,05). Thus, there seems to be a correspondence between mothers’ satisfactory experiences of continuity of care and implementation of strategies for continuity of care as reported by the midwives and CHC nurses.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to investigate strategies to achieve continuity of care for expectant and new mothers, as experienced by the midwives and CHC nurses, as well as new and expectant mothers. The two workplaces, namely, the family center and the medical center, enabled us to illustrate differences in strategies for the continuity of care between AC and CHC services located in the same premises and to further develop a preliminary model of linkage in the chain of care for expectant and new mothers.

There were two main findings in this study. The first was that, when staff perceived that strategies for continuity were both present and implemented jointly by different departments, mothers experienced continuity in the chain of care. Thus, we were able to describe continuity from the perspective of both the staff and the mothers.

The second finding was that all strategies for continuity described and implemented included joint action by the CHC nurses and midwives. In the family center, they acted together to provide breastfeeding support, parental education classes, and home visits, and they also interacted through informal meetings, knocking on each other’s door, and writing reports together. However, in the medical center, joint action was merely a vision. Visions of strategies or activities are not enough to induce action. Neither were mere visions of patient benefit or professional benefit sufficient to establish collaboration between professionals, as noted by D’Amour et al. (2005). In fact, joint action may be a prerequisite for the experience of professional benefit. However, when joint action is established, the experience of professional benefit may facilitate joint action. The paradoxical result that benefit is not experienced until collaboration has started was also noted by Huxham and Vangen (2004), who reported that the inertia of collaboration may dominate until collaboration is tried. Joint action also seemed to be a prerequisite for a chain of care perspective, i.e., when joint action was established, the professionals expressed a chain of care perspective. Axelsson and Axelsson (2009) stressed the importance of seeing beyond one’s own interests—a statement that is similar to emphasizing a chain of care perspective. One question that should be addressed further is whether the entire staff in a unit needs a chain of care perspective for joint action to be established or not. The staff in the medical center had diverse perspectives, whereas the entire staff in the family center expressed a chain of care perspective.

The strategies for continuity of care that have been described in the present study, transfer, establishing and maintaining a relation, and adjustment, correspond to established concepts of continuity of care, namely, informational, relational, and management (Haggerty et al., 2003; Pontin & Lewis, 2009), as illustrated in Table III.

Table III.

Strategies for continuity from this study compared to types of continuity.

| Strategies for continuity—joint action | Type of continuity |

|---|---|

| Transfer | Informational continuity |

| Establish and maintain relationship | Relational continuity |

| Adjustments | Management continuity |

Source: Haggerty et al. (2003).

Transfer/informational continuity

Informational continuity is the use of past information to make current care appropriate for each individual (Haggerty et al., 2003). It has been assessed in few studies that concern expectant and new mothers. Homer et al. (2009) identified three models for the transfer of information between AC and CHC: (1) structured nonverbal communication (obstetric summaries), (2) use of a case manager, and (3) purposeful face-to-face contact with high-risk mothers. It has been argued that when women are vulnerable, pathways of communication and purposeful face-to-face contact are of prime importance (Homer et al., 2009; Schmied et al., 2010). This is true for mothers who require special support after childbirth (Rubertsson et al., 2005). One obstacle to the transfer of information might be the concern about women’s confidentiality. This obstacle could be overcome by involving the mother in the interaction. In this study, during joint home visits, midwives, who knew the mother well, could transfer information to a CHC nurse without compromising the mother’s confidentiality.

Establishing and maintaining relationships/relational continuity

Relational continuity refers to an ongoing relationship between the patient and the caregiver and has been focused mainly on research into maternity care. Under such circumstances, it involves either an ongoing relationship between the midwife and the mother (Freeman, 2006) or team midwifery care throughout the antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum periods (Biro, Waldenström, Brown, & Pannifex, 2003; Waldenström, Rudman, & Hildingsson, 2006). Relational continuity of care has been reported consistently to increase patient satisfaction (Biro et al., 2003; Saultz & Albedaiwi, 2004). Relational continuity in maternity care is usually achieved in Sweden by providing the same midwife throughout pregnancy and the same CHC nurse during the child’s first 5 years. The findings of the study indicated that mothers lose touch with their midwife after the baby is born, which supports earlier evidence that mothers want more postpartum support (Waldenström et al., 2006). In the family center, relational continuity was created through joint parental education classes, joint home visits, breastfeeding support, and by “knocking on the door.”

Adjustment/management continuity

Management continuity involves the consistent and coherent management of a health condition in a manner that is responsive to a patient’s changing needs. It is facilitated by shared plans and protocols (Haggerty et al., 2003). Such consistency has been proposed to be important in the chain of maternity care (Yelland, Krastev, & Brown, 2009) with respect to breastfeeding (Hannula, Kaunonen, & Tarkka, 2008). Recommendations that have been given previously for management continuity in the chain of care for expectant and new mothers include a shared philosophy and framework (Schmied et al., 2010) and a care coordinator who has an overall picture of a mother’s needs (Homer et al., 2009). The importance of different services having the same policy for breastfeeding support has been shown (Hannula et al., 2008). The staff at the family center had shared and jointly written plans and protocols, which did not exist in the medical center.

Adjustment describes only a minor part of management continuity because our analysis was focused on strategies used by professionals other than those at management level at the workplace of interest. We can only conclude from this small sample that strategies for continuity proposed by managers were not sufficient for the strategies to be implemented. The family center had no such strategies, whereas the medical center had. However, this fact should not be interpreted as evidence for reduced importance of management coordination (Huxham & Vangen, 2004). Rather, it reflects the dominance of joint action as a facilitator for further joint action, a chain of care perspective, and professional benefit.

The presence of both AC and CHC departments under the same roof was also not sufficient to allow for strategies of continuity to be implemented. It is possible that even a staircase is an obstacle, and being located on the same floor may be a facilitating factor that merits further investigation.

We found that link position had no influence on implementation of strategies for continuity. Our assumption from the a previous study (Barimani & Hylander, 2008) that the last link in the chain of care, i.e., the CHC nurse, more easily acknowledged the professional benefit of strategies for continuity than did the first link, i.e., the midwife, was not supported by this study. When strategies for continuity of care were implemented, both midwives and CHC nurses thought they benefited equally. When no strategies for continuity of care were implemented, there were voices from both links stating that joint actions took too much time. Moreover, joint action may be so dominant a factor that other factors may lose their impact. Thus, the role of the link position needs to be further addressed.

Although our main aim was to investigate strategies for continuity of care, rather than the impediments to enacting those strategies, a point should be raised. Our conclusion, in accordance with the main result, is that the medical center did not implement visions of continuity because they never started any joint action. There may be several reasons for this, such as lack of time, the size of the group, and the many subgroups, all of which are known factors that influence collaboration within and between groups (Brown, 2001). These are all issues that require more studies for understanding how continuity of care for expectant and new mothers could be achieved.

The strength of the present study was that data were collected from several sources—documents, observations, and interviews with both mothers and health care professionals—in two different workplaces. Differences between the two workplaces in relation to socioeconomic factors, group size, and time spent at the same premises are factors that may have accounted for the differences in the prevalence of joint actions and mothers’ experiences of support and continuity. Had we had more time and resources, an additional sample from a workplace with a history of joint action between AC and CHC could have deepened our understanding of strategies for continuity. However, we did conduct as many interviews as seemed necessary for the main categories to be saturated, and the theoretical findings using grounded theory reported here were well grounded in the dataset collected. Although these findings may not be generalizable, the theoretical model may be applicable to similar contexts and could be used as a basis for reflection on how to promote continuity of care for new and expectant mothers and as an avenue for new studies.

In conclusion, continuity of care between AC and CHC may be achieved by joint action between CHC nurses and midwives through three distinct strategies, which mothers as well as staff recognize as important to achieve continuity of care. According to our model, joint action is more important than visions of strategies for continuity of care. Joint action promotes a chain of care perspective and professional benefit, which, in turn, may be facilitators of joint action and lead to patient benefit.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The study was conducted with support from the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet.

References

- Alizadeh V, Hylander I, Kocturk T, Tornkvist L. Counselling young immigrant women worried about problems related to the protection of ‘family honour’—From the perspective of midwives and counselors at youth health clinics. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science. 2010;24(1):32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelsson R, Axelsson S. B. Integration and collaboration in public health—A conceptual framework. International Journal of Health Planning Management. 2006;21(1):75–88. doi: 10.1002/hpm.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelsson S. B, Axelsson R. From territoriality to altruism in interprofessional collaboration and leadership. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2009;23(4):320–330. doi: 10.1080/13561820902921811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barimani M, Hylander I. Linkage in the chain of care: A grounded theory of professional cooperation between antenatal care, postpartum care and child health care. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2008;8:e77. doi: 10.5334/ijic.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biro M. A, Waldenström U, Brown S, Pannifex J. H. Satisfaction with team midwifery care for low- and high-risk women: A randomized controlled trial. Birth. 2003;30(1):1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2003.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumer H. Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. Group processes: Dynamics within and between groups. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant A, Charmaz K, editors. The Sage handbook of grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. Introduction, grounded theory research: Methods and practices. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman A. Social research methods. 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. London: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amour D, Ferrada-Videla M, San Martin Rodriguez L, Beaulieu M. D. The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: Core concepts and theoretical frameworks. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2005;19(1):116–131. doi: 10.1080/13561820500082529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman L. M. Continuity of career and partnership. A review of the literature. Women Birth. 2006;19(2):39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G. Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G, Strauss A. L. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Guvå G, Hylander I. Grounded theory, a theory generating resarch perspective. 1. uppl. ed. Stockholm, Sweden: Liber; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hallberg L. R.-M. The “core category” of grounded theory: Making constant comparisons. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Wellbeing. 2006;1:141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty J. L, Reid R. J, Freeman G. K, Starfield B. H, Adair C. E, McKendry R. Continuity of care: A multidisciplinary review. British Medical Journal. 2003;327(7425):1221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannula L, Kaunonen M, Tarkka M. T. A systematic review of professional support interventions for breastfeeding. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17(9):1132–1143. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homer C. S, Henry K, Schmied V, Kemp L, Leap N, Briggs C. ‘It looks good on paper’: Transitions of care between midwives and child and family health nurses in New South Wales. Women Birth. 2009;22(2):64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxham C, Vangen S. Doing things collaboratively: Realizing the advantage or succumbing to inertia? Organizational Dynamics. 2004;33(2):190–201. [Google Scholar]

- Hylander I. Toward a grounded theory of the conceptual change process in consulted-centered consultation. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation. 2003;14:263–80. [Google Scholar]

- Pontin D, Lewis M. Maintaining the continuity of care in community children’s nursing caseloads in a service for children with life-limiting, life-threatening or chronic health conditions: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2009;18(8):1199–1206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubertsson C, Wickberg B, Gustavsson P, Rådestad I. Depressive symptoms in early pregnancy, two months and one year postpartum-prevalence and psychosocial risk factors in a national Swedish sample. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2005;8(2):97–104. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saultz J. W, Albedaiwi W. Interpersonal continuity of care and patient satisfaction: A critical review. Annals of Family Medicine. 2004;2(5):445–451. doi: 10.1370/afm.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmied V, Mills A, Kruske S, Kemp L, Fowler C, Homer C. The nature and impact of collaboration and integrated service delivery for pregnant women, children and families. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19(23, 24):3516–3526. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundelin C, Håkansson A. The importance of the child health services to the health of children: Summary of the state-of-the-art document from the Sigtuna conference on child health services with a view to the future. Acta Pediatric Supplement. 2000;89(434):76–79. doi: 10.1080/080352500750027448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldenström U, Rudman A, Hildingsson I. Intrapartum and postpartum care in Sweden: Women’s opinions and risk factors for not being satisfied. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2006;85(5):551–560. doi: 10.1080/00016340500345378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yelland J, Krastev A, Brown S. Enhancing early postnatal care: Findings from a major reform of maternity care in three Australian hospitals. Midwifery. 2009;25(4):392–402. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]