Abstract

Patellofemoral pain (PFP) is a common injury and increased patellofemoral joint compression forces (PFJCF) may aggravate symptoms. Backward running (BR) has been suggested for exercise with reduced PFJCF.

The aims of this study were to (1) investigate if BR had reduced peak PFJCF compared to forward running (FR) at the same speed, and (2) if PFJCF was reduced in BR, to investigate which biomechanical parameters explained this. It was hypothesized that (1) PFJCF would be lower in BR, and (2) that this would coincide with a reduced peak knee moment caused by altered ground reaction forces (GRFs).

Twenty healthy subjects ran in forward and backward directions at consistent speed. Kinematic and ground reaction force data were collected; inverse dynamic and PFJCF analyses were performed.

PFJCF were higher in FR than BR (4.5±1.5; 3.4±1.4BW; p<0.01). The majority of this difference (93.1%) was predicted by increased knee moments in FR compared to BR (157±54; 124±51 Nm; p<0.01). 54.8% of differences in knee moments could be predicted by the magnitude of the GRF (2.3±0.3; 2.4±0.2BW), knee flexion angle (44±6; 41±7) and center of pressure location on the foot (25±11; 12±6%) at time of peak knee moment. Results were not consistent in all subjects.

It was concluded that BR had reduced PFJCF compared to FR. This was caused by an increased knee moment, due to differences in magnitude and location of the GRF vector relative to the knee. BR can therefore be used to exercise with decreased PFJCF.

Abbreviations: |GRF|, magnitude of the ground reaction force; BR, backward running; COPloc, location of the ground reaction force relative to the foot; COPlocFS, position of the center of pressure relative to the foot at foot strike; dPT, patellar tendon moment arm; Fq, quadriceps tendon force; FR, forward running; GRF, ground reaction force; Mk(max), peak knee moment; PFJCF, patellofemoral joint compression force; PFP, patellofemoral pain; RFq-Fpl, ratio of the quadriceps to patellar tendon force; TIP, telescopic inverted pendulum; αfoot, foot segment angular acceleration; αshank, shank segment angular acceleration; αthigh, thigh segment angular acceleration; θGRF, orientation of the ground reaction force relative to the ground; θK, knee flexion angle; θL, orientation of the lower limb segment in the TIP model (see Fig. 1)

Keywords: Patellofemoral pain, Running, Backward running, Rehabilitation, Patellofemoral joint compression force

1. Introduction

Patellofemoral pain (PFP) accounts for approximately 25% of knee injuries in athletes (Taunton et al., 2002). PFP patients are often not able to perform exercises like running, as increased patellofemoral joint compression forces (PFJCF) may aggravate PFP pathology.

Overloading of the patellofemoral joint in PFP patients could eventually lead to severe chronic injuries, such as osteoarthritis (Buckwalter and Brown, 2004). Conservative treatment (such as rehabilitation) is important to manage PFP (Dixit et al., 2007). Ideally rehabilitation enables return to normal performance of functional activities. In this process BR has been proposed as a useful phase between walking and running forward.

Although it has been reported that BR has lower PFJCF compared to FR, this may be due to methodological issues; as running speeds were lower for BR than FR trials (Flynn and Soutaslittle, 1995). Another study found no difference in PFJCF between FR and BR at similar, but unnaturally slow speed (Sussman et al., 2000). Further research is therefore required to establish differences between PFJCF in BR compared to FR at the same speed.

PFJCF is influenced by multiple inter-related factors: knee extensor moment, patellar moment arm, quadriceps muscle force and patellar tendon force. The quadriceps muscle force is related to the knee extensor moment and the patellar tendon moment arm and the patellar tendon force is dependent on the knee angle and the quadriceps force (Gill and O'Connor, 1996). The within subject differences in maximum PFJCF between FR and BR will therefore depend on the peak knee extensor moment and the knee angle at this peak moment.

The main factors that influence the knee moment are the magnitude of the ground reaction force (GRF), position of the knee relative to the GRF vector, and angular accelerations of the lower limb segments. Besides these individual biomechanical factors, propulsive mechanisms of BR and FR might also explain differences in PFJCF. The telescopic inverted pendulum (TIP) approach can be used to explore the predominant propulsive mechanisms in FR and BR (Jacobs and van Ingen Schenau, 1992; Papa and Cappozzo, 1999). Pendular movement, such as observed in walking, can be simulated by a simple inverted pendulum model where the stance limb is modeled as a rigid segment that rotates around the ankle (McGeer, 1990; Garcia et al., 1998). Such movement would have relatively low knee extensor and high hip flexor moments. Running on the other hand involves a large compression and passive recoil of the stance limb (telescopic motion) and can therefore be better modeled by a spring mass model (Seyfarth et al., 2002).

The aims of this study were to (1) investigate if BR had a reduced peak PFJCF compared to FR at the same speed, and (2) if this force was reduced in BR, to investigate how changes in relevant biomechanical parameters resulted in this reduced PFJCF. It was hypothesized that (1) PFJCF would be lower in BR compared to FR, and (2) that this would coincide with a reduced peak knee moment in BR as a result of GRF alterations in BR. Heel strike running has been associated with increased GRF (Lieberman et al., 2010) and foot ground contact has been found to be reversed in BR relative to FR; toe–heel contact in BR versus heel–toe contact in FR (Devita and Stribling, 1991). We therefore expected a lower GRF in BR.

2. Materials and methods

Twenty moderately active healthy subjects, without any recent knee injury or pain, were recruited for this study. They all had no experience in BR. Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the School of Healthcare Studies at Cardiff University, and written consent was obtained from all subjects.

The subjects were asked to run along a 7-m walkway in forward (FR) and backward (BR) directions at a speed between 2.8 and 3.4 m/s. A consistent running speed was achieved by providing verbal feedback on running speed. BR was demonstrated and subjects were given sufficient practice to become confident.

For each subject, three FR and BR condition trials were collected. Kinematic data were collected at 200 Hz using an eight camera VICON MX motion analysis system (Oxford Metrics Group Ltd., UK). 16 reflective markers were placed using the lower limb ‘Plug-in-Gait’ marker set. Ground reaction force data were collected at 1000 Hz using two Kistler force plates (Kistler Instruments Ltd., Switzerland).

Data of three subjects were excluded from analysis, due to missing pelvis markers during part of the data collection. The data of 17 subjects (7 males and 10 females, age: 28±6 years, height: 1.71±0.07 m and mass: 70.7±20.3 kg) was analyzed. Inverse dynamics calculations were performed within VICON Nexus software (version 1.6.1, Oxford Metrics Group Ltd., UK).

The peak PFJCF was estimated in Matlab (R2010b, The Mathworks Inc., USA), combining kinematic and kinetic data with values for the patellar tendon moment arm (dPT) from literature (Tsaopoulos et al., 2006). The dPT was extrapolated from average data in Tsaopoulos et al. (2006), excluding data from Buford et al. (1997) and Krevolin et al. (2004) as they used a different methodology to determine dPT. A polynomial was fitted to these extrapolated data, resulting in an equation for dPT based on knee angle (α), and body height. Tsaopoulos et al. (2006) demonstrated that dPT was expected to be scaled by body height, but not by body mass:

| (1) |

with

The PFJCF was calculated as follows:

| (2) |

with

| (3) |

and

| (4) |

where RFq-Fpl is the the ratio of the quadriceps to patellar tendon force, Fq is the quadriceps tendon force and Mk(max) is the peak knee moment. RFq-Fpl was extrapolated from Gill and O'Connor (1996, Eq. (4)).

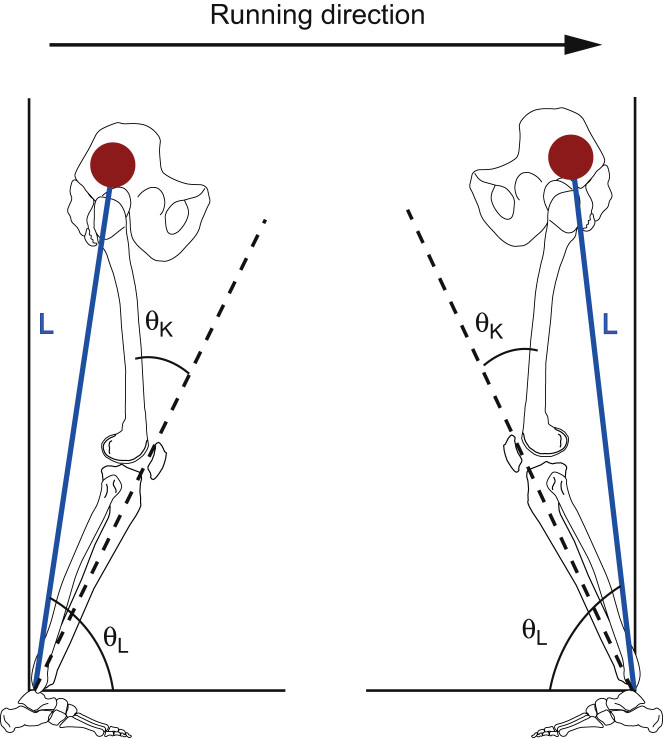

To investigate the kinematics and kinetics of BR and FR, a telescopic inverted pendulum (TIP) model approach was used, as described in the introduction (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic overview of telescopic inverted pendulum (TIP) model for forward running (FR) on the left and backward running (BR) on the right, with the approach angle (θL), knee angle (θK), and length (L) of the contact leg.

To further explore the underlying causes of differences in kinetics, the separate components that contribute to the knee joint moments were investigated. These are the GRF and the lower limb segment angular decelerations. The magnitude of the GRF was calculated at the time of peak knee moment (Mk(max)):

| (5) |

with Fy as the horizontal and Fz as the vertical component of the GRF.

The orientation of the GRF relative to the ground (θGRF) at the time of Mk(max) was calculated in the sagittal plane, with 0° being perpendicular to the ground, θGRF>0° pointing in anterior and θGRF<0° in posterior direction. The location of the GRF relative to the foot (COPloc) was calculated at the time of Mk(max) by dividing the distance between the projection of the center of pressure (COP) on the foot and the metatarsal marker by the length of the foot. The speed of the COP (COPdt) was calculated by differentiating COPloc. The position of the COP relative to the foot was also calculated at foot strike (COPlocFS), with foot–ground contact when the vertical Fz exceeded 5% BW.

The foot, shank and thigh segment angular accelerations (αfoot, αshank and αthigh) were calculated using the line between the calcaneus and metatarsal marker, the calcaneus and knee marker, and the ASI and knee marker respectively.

Statistical differences for the output variables between FR and BR were determined in SPSS (version 18.0.2) with an independent t-test. Stepwise linear regression analysis was used to investigate which variables most influenced PFJCF and subsequently Mk(max).

3. Results

Running speed was virtually identical between FR and BR (Table 1). The PFJCF and Mk(max) were significantly higher and the knee was slightly more flexed in FR (Table 1). Peak hip flexor moments (Mh(max)) were significantly higher in BR (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean running speed, patella femoral joint compressive force (PFJCF), peak knee moment (Mk(max)), knee angle at peak knee moment (θK), leg angle (θL) at peak knee moment (Mk(max)) and peak hip moment (Mh(max)) with standard deviations for forward and backward running. ⁎ indicates that the backward running condition was significantly different from forward running with p<0.05, and ⁎⁎ with p<0.01.

| Speed (m/s) | PFJCF(BW) | Mk(max) (Nm/BW) | θKatMk(max)(deg.) | θLatMk(max)(deg.) | Mh(max)(Nm/BW) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | 3.0±0.2 | 4.5±1.5 | 0.23±0.07 | 44±6 | 80±4 | 0.11±0.04 |

| Backward | 3.0±0.2 | 3.4±1.4⁎⁎ | 0.18±0.06⁎⁎ | 41±7⁎ | 82±3⁎⁎ | 0.16±0.04⁎⁎ |

| Significance | 0.46 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

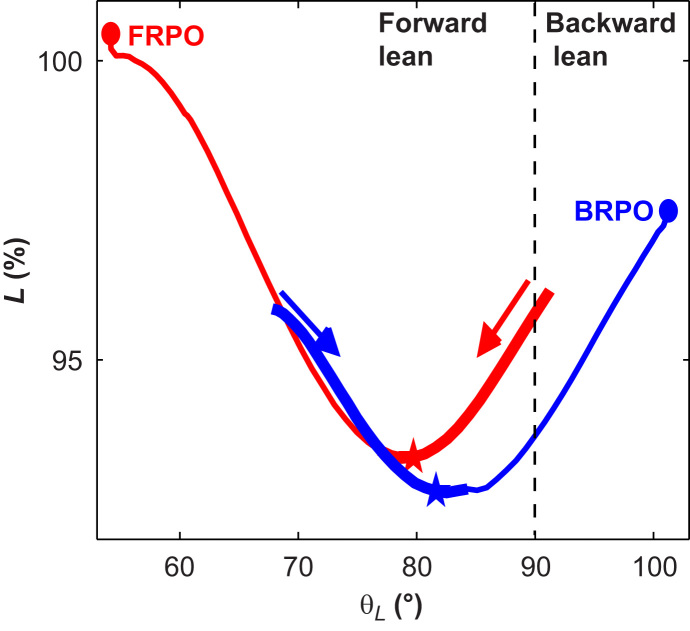

TIP model calculations (Fig. 2) showed that the stance leg is shortened during the deceleration phase and extended during the push-off phase in both FR and BR. In FR the stance leg flexed slightly more at Mk(max) (Table 1) and extended more during the push-off phase than in BR (Fig. 2). In both FR and BR, Mk(max) occurred at similar though significantly different approach angles of the contact leg (θL; Fig. 2, Table 1). Therefore in both situations the body was upright and leaning forward slightly at Mk(max) (as θL was close to, but smaller than 90°).

Fig. 2.

TIP model calculations with stance leg length (L) against θL. The blue lines are average data for backward running (BR) and the red lines for forward running (FR), with the thicker parts for the deceleration phase and the thinner parts for the push-off phase. FRPO and BRPO are push-off in FR and BR respectively, and the arrows indicate the walking directions. The stars indicate where Mk(max) occurred. In both FR and BR the leg shortened during the deceleration phase and extended during the push-off phase. The stars are very close together for FR and BR; the peak knee moment therefore occurred at similar body orientations for both running styles. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

There was no significant difference between FR and BR for the magnitude (|GRF|) and orientation of the GRF (θGRF) at Mk(max) (Table 2). The COP location on the foot (COPloc) at Mk(max) was further backward and moving slower forward along the foot in FR (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean size of the ground reaction force |GRF|, direction of the ground reaction force in the sagittal plane (θGRF), center of pressure location on the foot (COPloc, center of pressure speed in the sagittal plane (COPdt) at peak knee moment (Mk(max)) and center of pressure location on the foot at foot strike (COPlocFS), with standard deviations for forward and backward running. ⁎ indicates that the backward running condition was significantly different from forward running with p<0.05 and ⁎⁎ with p<0.01.

| |GRF|atMk(max)(BW) | θGRFatMk(max)(deg.) | COPlocatMk(max)(%) | COPdtatMk(max)(m/s) | COPlocFS(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | 2.3±0.3 | −4±3 | 25±11 | 0.4±0.3 | 55±26 |

| Backward | 2.4±0.2 | −4±2 | 12±6⁎⁎ | 0.7±0.5⁎⁎ | 1±16⁎⁎ |

| Significance | 0.51 | 0.109 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

The angular acceleration (αfoot) of the foot at Mk(max) was significantly different and in opposite directions between FR and BR (Table 3). The acceleration of the shank segment (αshank) at Mk(max) was in the same direction, but significantly smaller in FR (Table 3). There was no significant difference between the angular accelerations of the thigh segment (αthigh) at Mk(max) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean angular accelerations of the foot segment (αfoot), shank segment (αshank) and thigh segment (αthigh) at peak knee moment, with standard deviations for forward and backward running. ⁎ indicates that the backward running condition was significantly different from forward running with p<0.05 and ⁎⁎ with p<0.01.

| αfootatMk(max)(deg./s2) | αshankatMk(max)(deg./s2) | αthighatMk(max)(deg./s2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | 1351±1745 | 3420±1617 | −3048±1607 |

| Backward | −2976±2683⁎⁎ | 4228±931⁎⁎ | −3357±1179 |

| Significance | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.303 |

Stepwise regression analysis with the PFJCF as dependent variable and Mk(max), Mh(max), θK (knee flexion angle), θL, and |GRF| at Mk(max) as predictors confirmed that Mk(max) predicted the majority of variance in PFJCF (93.0%, adjusted R2=0.930). Another stepwise regression analysis with Mk(max) as the dependent variable and θK, θL, |GRF|, θGRF, COPloc, COPdt, αfoot, αshank, αthigh at Mk(max) as potential predictors showed that 54.8% (adjusted R2=0.548) of the variance in Mk(max) was predicted by θK, COPloc, and |GRF|.

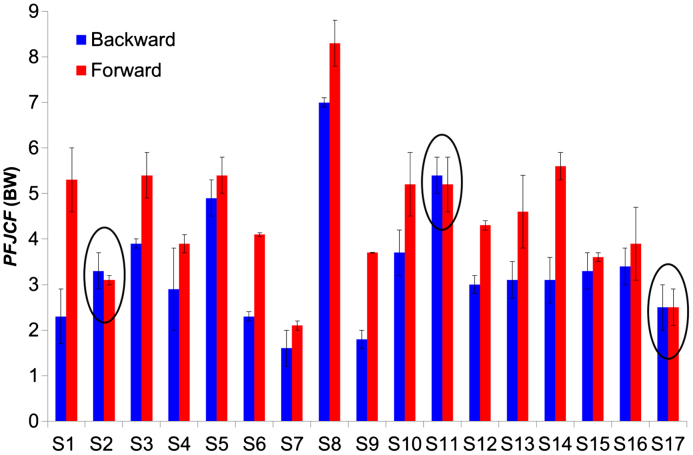

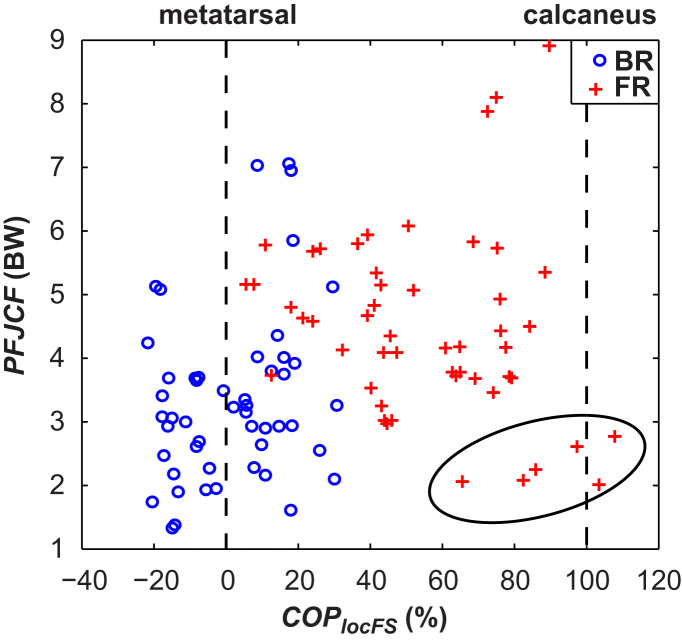

Interestingly, for three subjects PFJCF was not reduced in BR (Fig. 3). We investigated whether foot strike style could have an influence on PFJCF. The COP location on the foot at foot strike (COPlocFS) was closer to the forefoot in BR compared to FR (Table 2). When investigating FR and BR separately PFJCF was not correlated to COPlocFS; however when data were pooled there was a significant but weak correlation (R2=0.260 and p=0.008, as shown in Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Mean patellofemoral joint compressive force (PFJCF) with ±one standard deviation for each subject (S1–S17), with the blue bars for backward running (BR) and red bars for forward running (FR). The data of the subjects where PFJCF was higher or of similar magnitude in BR compared to FR are circled. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 4.

COP location on the foot at foot strike (COPlocFS) versus patellofemoral joint compression force (PFJCF), with the blue circles for backward running (BR) and the red crosses for forward running (FR). There was a significant correlation between PFJCF and COPlocFS (R2=0.26 and p=0.008). Note the circled outlying trials with COPlocFS close to the forefoot and a relatively low PFJCF. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

An almost identical running speed was achieved between BR and FR. PFJCF was significantly lower in BR than in FR and this difference was not due to running speed, confirming our first hypothesis. The reduction in PFJCF was lower than that found by Flynn and Soutaslittle (1995) (27% versus 46% decrease). The higher decrease in PFJCF observed by Flynn and Soutaslittle (1995) was most likely due to the difference in running speed between their FR and BR trials.

Kinematics at the peak knee moment (Mk(max)) were similar between BR and FR which seems consistent with an earlier study (van Deursen et al., 1998). However, kinetics differed with higher Mk(max) in FR and higher Mh(max) in BR. This predominantly agreed with Flynn and Soutaslittle (1995), as knee flexion angles were similar (FR: 44° and 38°, BR: 41° and 38°) and peak knee moments were similar for BR (124 and 123 Nm) but lower in FR (157 and 246 Nm).

TIP (telescopic inverted pendulum) analysis demonstrated that in both BR and FR Mk(max) occurred during the loading response, with the body upright and leaning slightly forward; Mk(max) thereby positively contributed to the support moment. The forward lean indicated that Mk(max) contributed to push-off in FR only, as in BR a backward lean would be required for Mk(max) to contribute to push-off. We propose that BR was predominantly generated by pendular movement. This was demonstrated by the reduced Mk(max) and increased Mh(max) in BR, which would be expected in pendular movement. Also, in FR the stance leg extended more during the push-off phase (and flexed slightly more during the deceleration phase) than in BR, consistent with our interpretation that FR involves a more telescopic movement.

Regression analysis showed that Mk(max) could predict the majority of the differences in PFJCF, confirming the first part of the second hypothesis that reduced PFJCF in BR was caused by a reduced Mk(max).

Although the magnitude (|GRF|) and orientation (θGRF) of the GRF at Mk(max) did not differ between BR and FR, the location of the GRF was further back on the foot in FR (larger COPloc). This would result in a larger moment arm between the GRF vector and the knee joint, as the knee flexion angle (θK) at Mk(max) was similar between BR and FR. Subsequently, this would result in a larger Mk(max).

Stepwise regression analysis showed that the variance in Mk(max) was best predicted by θK, COPloc and |GRF|. θK and COPloc both influence the magnitude of the moment arm of the GRF vector relative to the knee joint. Mk(max) therefore relied most on the position and magnitude of the GRF, partly confirming the second part of our second hypothesis. |GRF| was however not smaller in BR than in FR, as we hypothesized. The main factor influencing the peak knee moment was therefore COPloc, indicating that foot strike has a large impact on PFJCF. Although angular accelerations of the lower limb segments and joint angles were different between BR and FR trials, these were not significant predictors of Mk(max), and therefore are considered to have minimal influence on PFJCF.

The differences in PFJCF observed between BR and FR were not consistent in all subjects (Fig. 3). Investigation of the COP location at foot strike (COPlocFS) showed that this was closer to the heel in FR. There was a weak correlation between COPlocFS and PFJCF when FR and BR data were pooled. PFJCF was reduced if at foot strike the COP was closer to the forefoot. The relatively low PFJCF observed in some of the subjects during FR may therefore be due to running style (such as heel versus forefoot strike). We would expect lower knee moments resulting in lower PFJCF in forefoot strike runners, as they have lower loading rates of the foot (Oakley and Pratt, 1988) and a lower GRF (Lieberman et al., 2010). This agrees with our findings that PFJCF was reduced if the COP was closer to the forefoot. However, this conclusion did not apply to all subjects during FR (see Fig. 4, right lower corner). Clearly, further research is required to investigate whether it is the BR style that resulted in a reduced PFJCF or whether an adapted FR style could also be advised to PFP patients.

This study had several limitations; as PFJCF cannot be measured in vivo it was estimated with simplified models. This study focused on compressive forces only and did not include the direction and location of the forces acting on the patellofemoral joint. The use of more complex models of the knee and the additional calculation of patellofemoral joint stresses (ratio of PFJCF to the contact area (McGinty et al., 2000)) would have provided insight into the distribution and direction of the forces acting on the joint surface. There is however a strong relationship between the patellofemoral contact area and knee flexion angles (Salsich et al., 2003; Besier et al., 2005; Escamilla et al., 2008). As Mk(max) occurred at similar knee flexion angles in BR and FR, it can be assumed that the patellofemoral contact area would be comparable, and patellofemoral joint stresses would be directly related to PFJCF. Estimation of joint stresses requires complex and computationally intense methods (Farrokhi et al., 2011); as similar trends could be expected in patellofemoral joint stresses and compression forces between BR and FR, this study included compression forces only. Future research may involve more detailed analysis of the forces acting on the patellofemoral joint during backward and forward running.

The patellar tendon moment arm was important in the calculations of the PFJCF, as it defined the magnitude of the PFJCF relative to the knee moment. There is controversy in literature on how this moment arm should be estimated (Tsaopoulos et al., 2006). We assumed the patellar tendon moment arm depended on knee angle, as the majority of studies demonstrated that the patellar tendon moment arm changes significantly during the first 45° of knee flexion (Smidt, 1973; Herzog and Read, 1993; Baltzopoulos, 1995; Kellis and Baltzopoulos, 1999; Tsaopoulos et al., 2006, 2007), and only limited studies found the moment arm to change little with knee angle (Gill and O'Connor, 1996).

This study demonstrated that PFJCF was reduced in BR compared to FR, and that this was not due to a difference in running speed. It can be concluded that BR can be used as part of rehabilitation of PFP patients, to continue to exercise without increased PFJCF. Although BR can be suggested for rehabilitation, only a limited number of studies investigated BR as part of rehabilitation of knee injured patients. A case study showed that BR allowed exercising with decreased PFP; however if implemented incorrectly it can lead to overuse injury (Satterfield et al., 1993). Care therefore needs to be taken when implementing BR. Obviously, rehabilitation programs need to include other components, such as muscle strengthening (Dixit et al., 2007; Crossley et al., 2008), specific exercise therapy (Heintjes et al., 2003; Dixit et al., 2007) and/or taping (Dixit et al., 2007).

The reduced PFJCF in BR compared to FR may also prevent overloading and thereby the development of chronic conditions such as osteoarthritis. However PFJCF was not decreased in BR compared to FR in all subjects, and PFJCF was lower when the COP was closer to the forefoot. The COP location, that was closer to the heel at peak knee moment in FR than in BR, was the main predictor of the increased knee extensor moments. Certain FR styles may therefore also be able to reduce PFJCF, and could be useful in injury prevention or rehabilitation.

Conflict of interest statement

There are no known conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Roos is an Academic Fellow funded by Arthritis Research UK (Grant no. 18461).

References

- Baltzopoulos V. Muscular and tibiofemoral joint forces during isokinetic concentric knee extension. Clinical Biomechechanics. 1995;19:208–214. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(95)91399-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besier T.F., Draper C.E., Gold G.E., Beaupré G.S., Delp S.L. Patellofemoral joint contact area increases with knee flexion and weight-bearing. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2005;23(2):345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter J., Brown T. Joint injury, repair, and remodeling. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2004;423:7–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buford W.L., Ivey F.M., Malone J.D., Patterson R.M., Peare G.L., Nguyen D.K., Stewart A.A. Muscle balance at the knee–moment arms for the normal knee and the ACL-minus knee. IEEE Transactions on Rehabilitation Engineering. 1997;5(4):367–379. doi: 10.1109/86.650292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley K., Vicenzino B., Pandy M., Schache A., Hinman R. Targeted physiotherapy for patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis: a protocol for a randomised, single-blind controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2008;8:122. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devita P., Stribling J. Lower-extremity joint kinetics and energetics during backward running. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1991;23:602–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit S., DiFiori J.P., Burton M., Mines B. Management of patellofemoral pain syndrome. American Family Physician. 2007;75(2):194–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escamilla R., Zheng N., MacLeod T., Edwards W., Hreljac A., Fleisig G., Wilk K., Moorman C., Imamura R. Patellofemoral compressive force and stress during the forward and side lunges with and without a stride. Clinical Biomechanics. 2008;23(8):1026–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrokhi S., Keyak J., Powers C. Individuals with patellofemoral pain exhibit greater patellofemoral joint stress: a finite element analysis study. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2011;19(3):287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn T., Soutaslittle R. Patellofemoral joint compressive forces in forward and backward running. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 1995;21:277–282. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1995.21.5.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia M., Chatterjee A., Ruina A., Coleman M. The simplest walking model: stability, complexity, and scaling. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering—Transactions of the ASME. 1998;120:281–288. doi: 10.1115/1.2798313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill H., O'Connor J. Biarticulating two-dimensional computer model of the human patellofemoral joint. Clinical Biomechanics. 1996;11:81–89. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(95)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintjes E., Berger M.Y., Bierma-Zeinstra S.M., Bernsen R.M., Verhaar J.A., Koes B.W. Exercise therapy for patellofemoral pain syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003:4. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog W., Read L. Lines of action and moment arms of the major force-carrying structures crossing the human knee-joint. Journal of Anatomy. 1993;182:213–230. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs R., van Ingen Schenau G.J. Intermuscular coordination in a sprint push-off. Journal of Biomechanics. 1992;25(9):953–965. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(92)90031-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellis E., Baltzopoulos V. In vivo determination of the patella tendon and hamstrings moment arms in adult males using videofluoroscopy during submaximal knee extension and flexion. Clinical Biomechanics. 1999;14(2):118–124. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(98)00055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krevolin J., Pandy M., Pearce J. Moment arm of the patellar tendon in the human knee. Journal of Biomechanics. 2004;37(5):785–788. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman D., Venkadesan M., Werbel W., Daoud A., D'Andrea S., Davis I., Mang'Eni R., Pitsiladis Y. Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners. Nature. 2010;463:531–535. doi: 10.1038/nature08723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer T. Passive dynamic walking. International Journal of Robotics Research. 1990;9(2):62–82. [Google Scholar]

- McGinty G., Irrgang J.J., Pezzullo D. Biomechanical considerations for rehabilitation of the knee. Clinical Biomechanics. 2000;15(3):160–166. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(99)00061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley T., Pratt D. Skeletal transients during heel and toe strike running and the effectiveness of some materials in their attenuation. Clinical Biomechanics. 1988;3:159–165. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(88)90062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa E., Cappozzo A. A telescopic inverted-pendulum model of the musculo-skeletal system and its use for the analysis of the sit-to-stand motor task. Journal of Biomechanics. 1999;32(11):1205–1212. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salsich G.B., Ward S.R., Terk M.R., Powers C.M. In vivo assessment of patellofemoral joint contact area in individuals who are pain free. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2003;417:277–284. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000093024.56370.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterfield M., Yasumura K., Abrue S. Retro runner with ischial tuberosity enthesopathy. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 1993;17(4):191–194. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1993.17.4.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyfarth A., Geyer H., Gunther M., Blickhan R. A movement criterion for running. Journal of Biomechanics. 2002;35(5):649–655. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00245-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smidt G. Biomechanical analysis of knee flexion and extension. Journal of Biomechanics. 1973;6:79–92. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(73)90040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman D., Alrowayeh H., Walker M. Patellofemoral joint compressive forces during backward and forward running at the same speed. Journal of Musculoskeletal Research. 2000;4(2):107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Taunton J., Ryan M., Clement D., McKenzie D., Lloyd-Smith D., Zumbo B. A retrospective case-control injuries analysis of 2002 running. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2002;36:95–101. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.2.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsaopoulos D., Baltzopoulos V., Maganaris C. Human patellar tendon moment arm length: Measurement considerations and clinical implications for joint loading assessment. Clinical Biomechanics. 2006;21:657–667. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsaopoulos D., Maganaris C., Baltzopoulos V. Can the patellar tendon moment arm be predicted from anthropometric measurements? Journal of Biomechanics. 2007;4(3):645–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Deursen R., Flynn T., McCrory J., Morag E. Does a single control mechanism exist for both forward and backward walking? Gait and Posture. 1998;7:214–224. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(98)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]