Abstract

Characterization of the viscoelastic material properties of soft tissue has become an important area of research over the last two decades. Our group has been investigating the feasibility of using Shearwave Dispersion Ultrasound Vibrometry (SDUV) method to excite Lamb waves in organs with plate-like geometry to estimate the viscoelasticity of the medium of interest. The use of Lamb wave Dispersion Ultrasound Vibrometry (LDUV) to quantify mechanical properties of viscoelastic solids has previously been reported. Two organs, the heart wall and the spleen, can be readily modeled using plate-like geometries. The elasticity of these two organs is important because they change in pathological conditions. Diastolic dysfunction is the inability of the left ventricle (LV) of the heart to supply sufficient stroke volumes into the systemic circulation and is accompanied by the loss of compliance and stiffening of the LV myocardium. It has been shown that there is a correlation between high splenic stiffness in patients with chronic liver disease and strong correlation between spleen and liver stiffness. Here, we investigate the use of the SDUV method to quantify viscoelasticity of the LV free-wall myocardium and spleen by exciting Rayleigh waves on the organ’s surface and measuring the wave dispersion (change of wave velocity as a function of frequency) in the frequency range 40–500 Hz. An equation for Rayleigh wave dispersion due to cylindrical excitation was derived by modeling the excised myocardium and spleen with a homogenous Voigt material plate immersed in a nonviscous fluid. Boundary conditions and wave potential functions were solved for the surface wave velocity. Analytical and experimental convergence between the Lamb and Rayleigh waves is reported in a finite element model of a plate in a fluid of similar density, gelatin plate and excised porcine spleen and left-ventricular free-wall myocardium.

INTRODUCTION

Characterization of the viscoelastic material properties of soft tissue has become an important area of research over the last two decades. Recently, our group has reported the use of Lamb wave Dispersion Ultrasound Vibrometry, or LDUV, to quantify viscoelasticity of soft tissues with plate-like geometry [1, 2]. LDUV uses focused ultrasound radiation force or a mechanical actuator to excite anti-symmetric Lamb waves in the region of interest and pulse-echo ultrasound to measure Lamb wave velocity at multiple excitation frequencies (Lamb wave dispersion). The Lamb wave dispersion equation is fit to the Lamb wave velocity dispersion to estimate viscoelasticity of the tissue. Studies aimed at validating the LDUV method and measurements of viscoelasticity of gelatin and urethane plates as well as excised porcine left ventricular (LV) free-wall myocardium are reported in Nenadic, et al.[2].

Diastolic dysfunction is associated with the loss of left-ventricular compliance and stiffening of the left-ventricular myocardium [3–5] and accounts for close to half of heart failures in the United States [4, 6]. Changes in myocardial stiffness due to pathophysiology have prompted significant effort towards producing a method for non-invasive measurement of myocardial stiffness, mostly using ultrasound [1, 7–12] or magnetic resonance elastography [13–15].

In addition, recent studies of splenic elasticity have shown correlation between high splenic stiffness in patients with chronic liver disease and strong correlation between spleen and liver stiffness [16–18]. Studies of liver fibrosis [19, 20] and myocardial ischemia [21] suggest that pathophysiological alterations of the tissue result in changes in both elasticity and viscosity.

The myocardium and spleen can be modeled as plate-like viscoelastic materials. Thus, a method for quantifying viscoelasticity of plate-like tissues like LDUV could provide clinicians with a valuable diagnostic tool.

In vivo measurements of tissue viscoelasticity using LDUV would require excitation of anti-symmetric Lamb waves in the middle of the organ. Focusing radiation force in the middle of moving myocardial tissue could prove to be difficult due to physiological periodical motion of the heart and higher power necessary to move the entire heart wall. The epicardial surface, however, is highly reflective and is readily visible on the echocardiogram. Focusing the radiation force on the outer surface of the left-ventricular myocardium would not only be easier, but would also increase the radiation force [22].

Vibrating the organ surface with a mechanical actuator or radiation force would excite surface, or Rayleigh waves, whose geometry, motion and dispersion are different than in Lamb waves.

In this paper, we investigate the differences between Lamb and Rayleigh wave velocity dispersion and different waves formed due to excitation on the surface versus the interior of the organ. Theoretical solutions for Lamb and Rayleigh wave velocity dispersion were derived. Finite element analysis of Lamb and Rayleigh wave propagation in viscoelastic plates submerged in an incompressible fluid was used to validate the theory. Experimental setups for Lamb wave Dispersion Ultrasound Vibrometry (LDUV) and Rayleigh wave Ultrasound Vibrometry (RDUV) are presented. Lamb and Rayleigh wave studies in gelatin, excised porcine myocardium and spleen samples are reported.

METHODS

A. Principles of Shearwave Dispersion Ultrasound Vibrometry (SDUV)

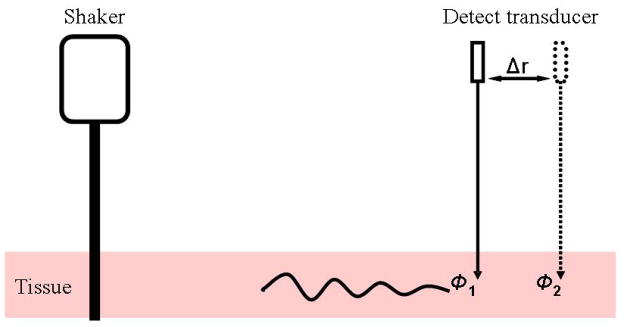

Focused radiation force or a mechanical actuator (shaker) is used to excite harmonic waves in the frequency range 50–500 Hz (Figure 1). A pulse-echo transducer is used to track the motion by transmitting pulses to the location of interest at a pulse repetition rate of several kilohertz. Cross-spectral analysis of the echoes and a specialized Kalman filtering of the displacement versus time data are used to calculate amplitude and phase of the motion at each frequency.

Figure 1.

Principle of SDUV: a mechanical actuator (shaker) induces harmonic shear wave propagation in tissue; the motion is measured by a pulse-echo transducer.

The shear wave velocity is estimated by measuring the phase at two different points Δr apart and using

| (1) |

where Δφ = φ2 − φ1 is the phase difference, ω = 2πf and f the excitation frequency. In practice, the phase is measured over several points away from the excitation to decrease the uncertainty [23].

B. Rayleigh and Lamb wave Dispersion in Plates

What follows is the derivation of the Rayleigh wave dispersion equation due to axisymmetric waves in a homogenous medium. The derivation of the anti-symmetric Lamb wave dispersion equation for an axisymmetric plate is presented in our earlier work [2] and will be summarized at the end of this section.

Rayleigh wave Dispersion Equation

Development of the equations (2)-(33) governing the motion of a solid can be found in [24–26]. Applying the Stokes-Helmholtz decomposition theorem u = ∇φ + ∇ × ψ to the Navier’s equation with zero equivalent body force (2) results in equations (3) and (4):

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

where u is the displacement field vector, ∇• is the divergence operator, ∇× is the curl operator, and ∇ is the gradient operator. Functions φ and ψ are the compressional and shear wave potential functions, cp the compressional wave velocity, cs the shear wave velocity, ρ the material density, λ the first Lamé constant and μ the second Lamé constant.

Rayleigh waves are surface waves not affected by the lower boundary of the solid and can therefore be considered shear waves in a semi-infinite medium. A Rayleigh wave in a plate of finite thickness 2h excited by a point source on the surface of the plate at z = H does not “see” the bottom surface at z = 0 and has no contribution from wave reflection from that surface (Figure 2(b)). In other words, the excitation wave is completely attenuated before it reaches the lower boundary.

Figure 2.

Motion of viscoelastic solids. (a) Anti-symmetric Lamb wave motion, (b) Rayleigh wave motion.

If we consider an axially symmetric plate, i.e. the motion is independent of the angle θ (Figure 2), then uθ;= ∂/∂θ = 0. Introducing this assumption into the Stokes-Helmholtz decomposition and expressing the differential operators in cylindrical coordinates results in the following equations:

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

where cp and cs are the compressional and shear wave velocities in the solid, and cF is the compressional wave velocity in the fluid. Subscripts 1 and 2 refer to the fluid and the solid, respectively. Since shear waves do not propagate in fluids, the shear wave potential for the fluid is ignored. The Rayleigh wave boundary conditions at z = H are σzz1 = σzz2, σrz2 = 0 and uz1 = uz2, where the displacements (u) and stresses (σ) are defined in as follows:

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

Differential equations (7)–(9) are not easily solved, so we perform the one-sided Laplace transform with respect to time (t) (16) and the nth-order Hankel transform with respect to the radial component (r) (17) [27, 28].

| (16) |

| (17) |

Here, f(t)and f(r) are functions of time (t) and distance (r), and Jn is the Bessel function of first kind. Following the Hankel and Laplace transforms equations (7)–(9) become:

| (18) |

| (19) |

| (20) |

where α1, α2 and β are defined as and , where p and ξ are the Laplace and Hankel domain variables. The solutions of the potential functions (18)–(20) are of the following form:

| (21) |

| (22) |

| (23) |

The potential functions must be stable in the region of interest (i.e. cannot approach infinity) so (21)–(23) simplify as follows:

| (24) |

| (25) |

| (26) |

In order to use (24)–(26), the displacements (u) and stresses (σ) have to be expressed in the Hankel-Laplace domain:

| (27) |

| (28) |

| (29) |

| (30) |

| (31) |

| (32) |

| (33) |

Introducing the potential functions (24)–(26) into the definitions of stress and displacement in equations (27)–(33) yields the following expression:

| (34) |

This is the dispersion relationship for axisymmetric Rayleigh waves in a viscoelastic solid submerged in a water-like fluid. Note that the difference between the bilateral Laplace (35) and Fourier transform (36) is the variable p = iω.

| (35) |

| (36) |

By introducing the substitution ξ = ηp and recognizing that η = ±i/cR, where cR is the Rayleigh wave velocity [26, 27], equation (34) becomes the Rayleigh wave dispersion equation for the case of axially symmetric motion (37):

| (37) |

Here, and kf is the compressional wave number for the fluid. The compressional wave numbers for the tissue and blood (kp and kf) are similar and about four orders of magnitude smaller than the shear wave number (ks) which is similar to the Rayleigh wave number (kR). Thus, . In addition, the density of the blood is similar to that of myocardium, so the Rayleigh wave dispersion equation (37) can be expressed as follows:

| (38) |

where kR = ω/cR is the Rayleigh wave number, ω is the angular frequency, cR is the frequency dependent Rayleigh wave velocity, is the shear wave number, and ρm is the density of the sample.

Lamb wave Dispersion Equation

As shown in our previous work [2], the derivation of the Lamb wave dispersion equation follows the same course as that for the Rayleigh up to equation (23). Here, we briefly summarize the theoretical development of the axially symmetric anti-symmetric Lamb wave in a plate.

The solutions (21)–(23) still apply, but due to differences in geometry, we have to consider the potentials for the fluid above and below the solid separately. By employing definitions of hyperbolic sine and cosine functions 2sinh(x) = (ex − e−x ) and 2cosh(x) = (ex + e−x), we can rewrite equations (21)–(23) as follows:

| (39) |

| (40) |

| (41) |

| (42) |

Here, subscripts L and U represent the lower and upper fluid on either side of the solid (Figure 2(a)). In the case of anti-symmetric Lamb waves, the displacement of the solid in the z-direction is anti-symmetric relative to the r-axis, so the potential functions (39) and (40) simplify as follows:

| (43) |

| (44) |

The boundary conditions for anti-symmetric Lamb wave motion are the same as for the Rayleigh wave motion, but they have to be satisfied on both surfaces of the plate, i.e. at z = ±h. Solving for the boundary conditions yields the anti-symmetric Lamb wave dispersion equation due to cylindrical waves:

| (45) |

which can be shown to be identical to the plane Lamb wave dispersion relationship as shown in (46).

| (46) |

In (46), , kf is the wave number of the compressional wave in the fluid, kL = ω/cL is the Lamb wave number, ω is the angular frequency, cL is the frequency dependent Lamb wave velocity, is the shear wave number, ρm is the density of the sample, h is the half-thickness of the sample and μ is shear modulus. In case of tissue submerged in blood or water, it can be shown that (46) simplifies to (47) [2], which can be divided by cosh(kL h)cosh(βh), yielding (48):

| (47) |

| (48) |

| (49) |

| (50) |

Since , tanh(kLh) → 1and the sample thickness is constant, Lamb wave dispersion equation (48) converges to the Rayleigh wave dispersion equation (38) as the frequency increases.

C. Finite Element Analysis (FEA) of a Plate in a Fluid

A finite element model of a solid viscoelastic plate (0.5 m × 0.5 m × 2 cm) submerged in an incompressible fluid was designed using ABAQUS 6.8–3 (SIMULIA, Providence, RI). The fluid surrounding the plate was represented with acoustic elements with a bulk modulus of 2.2 GPa and density of 1 g/cm3. The material properties of the plate were as follows: density of 1.08 g/cm3, Poisson’s ratio of 0.495, Young’s modulus of 90 kPa and the material properties defined in terms of the two parameter Prony series where g1 = 0.5 and t1 = 10−6. The two parameter Prony series is directly related to the generalized Maxwell model with three parameters [29]. A line source through the entire thickness of the plate was used to excite anti-symmetric Lamb waves. A point source on the surface of the plate was used to excite Rayleigh waves. Motion characteristic of the Rayleigh waves and anti-symmetric Lamb waves was produced by oscillating the respective sources with four cycles of sinusoidal waves in the frequency range 25–600 Hz with the displacements in tens of micrometers. Shear wave displacements were recorded at 40 points, 1 mm apart, along a line away from the source in the middle of the plate. Phase was calculated at each point and equation c = ω(Δr/Δφ) was used to calculate the Rayleigh and Lamb wave velocities at each frequency. The dispersion data was compared to theoretical predictions to study the validity of the Lamb and Rayleigh wave dispersion equations.

D. Materials

Gelatin plate samples consisted of 70% water, 15% glycerol and 15% of 300 Bloom gelatin (all manufactured by Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), all by volume. Plate phantoms were prepared by pouring the mixtures into an 11 cm × 8 cm × 1.2 cm plastic mold and allowed to cure for 24 hours. Pig heart and spleen samples were obtained from a local butcher shop. The organs were obtained a few hours after the animals were sacrificed. Left ventricular free-wall myocardium was excised from the pig hearts in our laboratory. The spleen samples used in our study were excised from the middle third of the spleen in our laboratory. Both the porcine spleen and myocardium samples were embedded in gelatin and stored overnight in a refrigerator before testing.

E. Experimental Setup

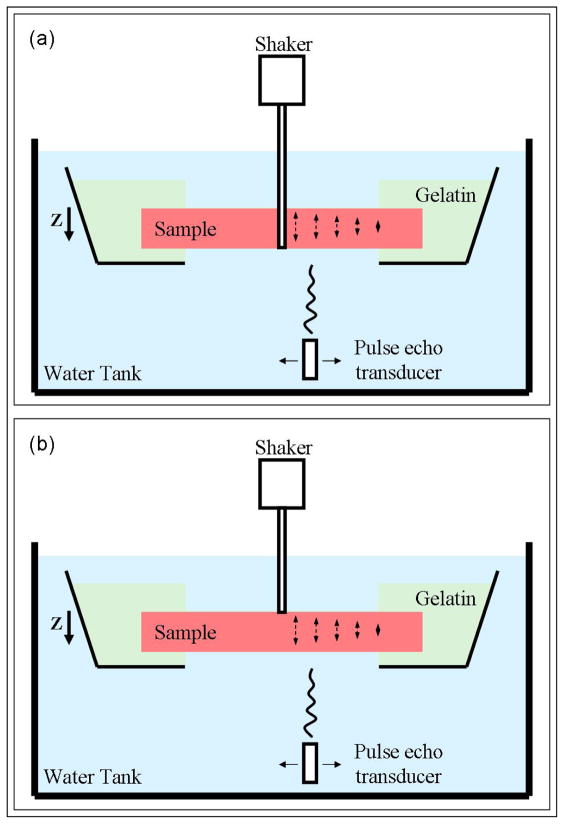

The following procedure was followed for gelatin plates, excised porcine spleen, and excised porcine LV free-wall myocardium samples. The samples were embedded in a gelatin mixture (70% water, 10% glycerol, 10% 300 Bloom gelatin, 10% potassium sorbate preservative, all by volume and all manufactured by Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) inside a plastic container. The container was mounted on a stand in a water tank (Figure 3). A window was cut out on the bottom of the container to allow for motion detection. The gelatin was used as a stabilizer and was contained to the edges to minimize the affect of mechanical coupling. A mechanical shaker (V203, Ling Dynamic Systems Limited, Hertfordshire, UK) was used to excite Rayleigh and Lamb waves. A glass rod coupled with the shaker was glued to the hole bored through the thickness of the sample to excite anti-symmetric Lamb waves (Figure 3(a)). A ballpoint rod coupled with the shaker was attached to the surface of the samples to excite Rayleigh waves (Figure 3(b)). Four cycles of sinusoidal waves were used to drive the shaker at different frequencies ranging from 50 to 500 Hz to induce cylindrical shear waves in the samples. The phantom displacement was on the order of tens of micrometers. The motion was attenuated within 2–3 cm from the source and did not reach the gelatin boundary. Motion was measured at each frequency along the line of propagation using a single element spherically focused 7.5 MHz pulse-echo transducer with the focal length of 3 cm, operating at the pulse repetition rate of 4 kHz. Motion was recorded at 31 points along a line, 0.5 mm apart. Cross-spectral correlation and Kalman filtering were used to extract the phase at each point. Phase estimates at these points were used to fit a regression curve and calculate the shear wave speed at each frequency, as described in the SDUV method [23].

Figure 3.

Experimental setups for Lamb and Rayleigh wave experiments. (a) Experimental LDUV wave excitation: A glass rod coupled with a mechanical actuator (shaker) was glued to the hole in the middle of the samples in order to excite Lamb waves. A pulse-echo transducer was used to track the motion at several points away from the excitation. (b) Experimental RDUV excitation: A ballpoint rod coupled with a mechanical actuator (shaker) was attached to the surface of the samples in order to excite Rayleigh (surface) waves. A pulse-echo transducer was used to track the motion at several points away from the excitation.

RESULTS

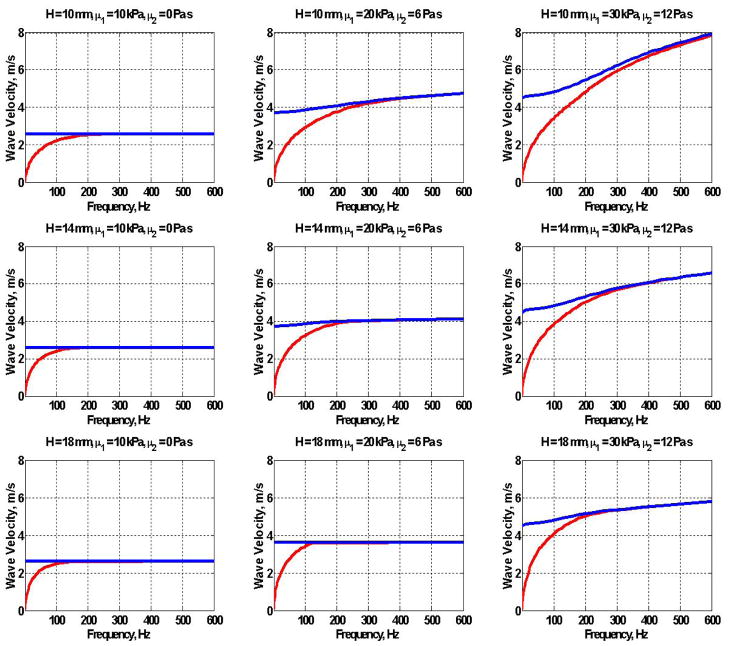

Equations (38) and (47) were used to plot Lamb and Rayleigh dispersion curves for several thicknesses of the plate H and values of shear wave elasticity (μ1) and viscosity (μ2) (Figure 4). Here, we are assuming that the medium has the frequency response of a Voigt material so that the shear modulus μ = μ1 + iωμ2. The Lamb wave dispersion equation (47) is shown in red and the Rayleigh wave (38) in blue.

Figure 4.

Analytical dispersion curves for the Lamb (

) and Rayleigh (

) and Rayleigh (

) wave dispersion for a plates of thickness H = 10, 14 and 18 mm, μ1 = 10, 20 and 30 kPa and μ2 = 0, 6 and 12 Pa·s.

) wave dispersion for a plates of thickness H = 10, 14 and 18 mm, μ1 = 10, 20 and 30 kPa and μ2 = 0, 6 and 12 Pa·s.

A finite element model of a viscoelastic isotropic plate submerged in a fluid of similar density was used to compare the wave dispersion velocity due to Lamb and Rayleigh wave excitation. Lamb and Rayleigh excitation methods were used to excite harmonic waves in the range 25–600 Hz. The phase gradient equation (1) was used to calculate the velocity at each frequency for each method of excitation. Figure 5 shows the wave velocity dispersion in an FEA simulation obtained using the Lamb wave excitation method as green circles and Rayleigh as black squares.

Figure 5.

FEA dispersion data obtained using the LDUV (

) and RDUV (□) excitation methods are in good agreement with the theoretical Lamb wave dispersion curve (47) for a plate with the mechanical properties defined in the simulation.

) and RDUV (□) excitation methods are in good agreement with the theoretical Lamb wave dispersion curve (47) for a plate with the mechanical properties defined in the simulation.

The mechanical properties of the plate in the FEA simulation were inserted into the shear wave modulus μ in the Rayleigh (38) and Lamb wave dispersion equations (47). The Rayleigh dispersion equation (38) is plotted in blue and the Lamb dispersion equation (47) in red in Figure 5.

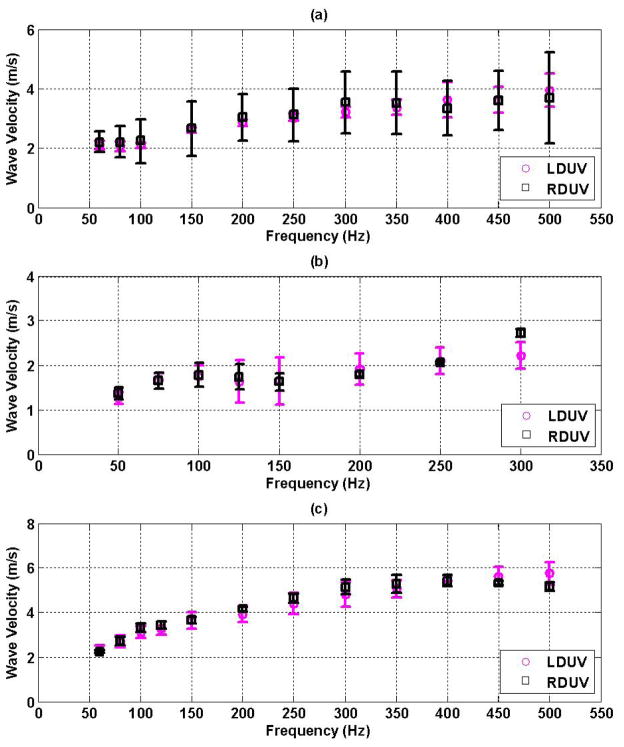

LDUV and RDUV experimental approaches were used to measure wave dispersion in a gelatin phantom and excised porcine spleen and heart samples. Figure 6(a)–(c) shows the experimental dispersion data obtained using the LDUV (

) and the RDUV approaches (□) for a gelatin plate in 6(a), excised porcine spleen in 6(b) and excised porcine LV myocardium in 6(c). The wave dispersion was measured for each millimeter of sample thickness and the mean and standard deviation through the thickness are reported for each frequency.

) and the RDUV approaches (□) for a gelatin plate in 6(a), excised porcine spleen in 6(b) and excised porcine LV myocardium in 6(c). The wave dispersion was measured for each millimeter of sample thickness and the mean and standard deviation through the thickness are reported for each frequency.

Figure 6.

Lamb (

) and Rayleigh (□) wave dispersion velocity in: (a) gelatin plates, (b) excised porcine spleen and (c) excised porcine left-ventricular free wall myocardium.

) and Rayleigh (□) wave dispersion velocity in: (a) gelatin plates, (b) excised porcine spleen and (c) excised porcine left-ventricular free wall myocardium.

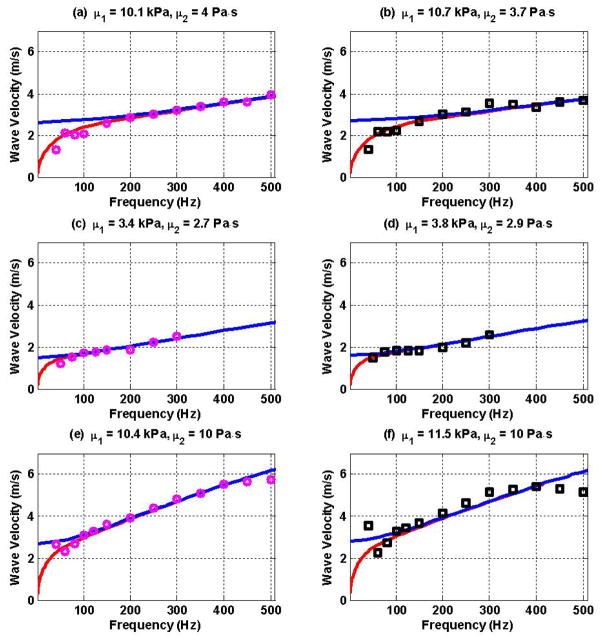

Dispersion data obtained using the LDUV and RDUV methods were fitted with the Lamb wave dispersion equation (47) in order to estimate elasticity (μ1) and viscosity (μ2) using two methods. Figures 7(a) and 7(b) show the gelatin dispersion data due to LDUV and RDUV excitation, respectively. The estimated elasticity (μ1) and viscosity (μ2) are shown above each panel. Figures 7(c) and 7(d) show the LDUV and RDUV measurements for the spleen sample while 7(e) and 7(f) show the same results for the excised pig heart sample.

Figure 7.

LDUV (

) and RDUV (□) data were fitted with the Lamb wave dispersion equation to estimate elasticity (μ1) and viscosity (μ2) of the materials (a) LDUV gelatin, (b) RDUV gelatin, (c) LDUV spleen, (d) RDUV spleen, (e) LDUV heart, (f) RDUV heart. The Lamb wave dispersion equation (47) is shown in red. The Rayleigh wave dispersion equation (38) is shown in blue for comparison.

) and RDUV (□) data were fitted with the Lamb wave dispersion equation to estimate elasticity (μ1) and viscosity (μ2) of the materials (a) LDUV gelatin, (b) RDUV gelatin, (c) LDUV spleen, (d) RDUV spleen, (e) LDUV heart, (f) RDUV heart. The Lamb wave dispersion equation (47) is shown in red. The Rayleigh wave dispersion equation (38) is shown in blue for comparison.

DISCUSSION

Finite element analysis of Lamb and Rayleigh wave dispersion in a viscoelastic plate submerged in a fluid of similar density shows similarity between the two types of dispersion (

and □ in Figure 5). The Lamb wave dispersion equation (47) for a plate with mechanical properties defined in the simulation is in a good agreement with the FEA data suggesting validity of the Lamb wave model for both the LDUV and RDUV excitation methods (Figure 5). Rayleigh wave dispersion equation (38) was plotted in Figure 5 for comparison and does not agree with the dispersion data for frequencies below 300 Hz.

and □ in Figure 5). The Lamb wave dispersion equation (47) for a plate with mechanical properties defined in the simulation is in a good agreement with the FEA data suggesting validity of the Lamb wave model for both the LDUV and RDUV excitation methods (Figure 5). Rayleigh wave dispersion equation (38) was plotted in Figure 5 for comparison and does not agree with the dispersion data for frequencies below 300 Hz.

At low excitation frequencies, the wavelengths of excitatory waves are fairly large and have low attenuation. Thus, low frequency surface tapping waves propagate through the thickness of the plate, reflect from the bottom surface and establish an interference pattern, much like in Lamb waves. In other words, surface excitation at “low” frequencies can “feel” the lower boundary of the plate, resulting in an anti-symmetric Lamb wave. The cutoff frequency at which surface excitation establishes Rayleigh waves depends on the thickness and the mechanical properties of the plate, as shown in (47)–(50).

Thus, both LDUV and RDUV excitation methods produce Lamb wave motion at lower frequencies. At higher excitation frequencies where the Rayleigh waves cannot “feel” the bottom surface, Lamb and Rayleigh dispersion curves have already converged and the velocities are again similar. Thus, both the LDUV and RDUV excitation methods produce similar velocities and both can be fitted using the Lamb wave dispersion equation.

The experimental measurements of wave dispersion using LDUV and RDUV approaches agree within one standard deviation for gelatin, excised spleen and excised heart samples (Figure 6(a)–(c)) suggesting that either method can be used to obtain wave dispersion curve data in plate-like tissues.

The Lamb wave dispersion equation fits the LDUV and RDUV experimental data well (Figure 7(a)–(f)). The estimated values of elasticity (μ1) and viscosity (μ2) for the gelatin, spleen and heart samples using two excitation methods are in good agreement. These results suggest that surface excitation of Lamb-Rayleigh waves is a feasible method for quantifying viscoelasticity of soft materials with a plate-like geometry, including the left-ventricular free-wall myocardium and spleen. Figure 7(f) shows slight disagreements between the experimental data and the fitted model. We speculate this is due to the limitations of the Voigt model and errors in velocity estimates at higher frequencies due to smaller motion.

The dispersion measurements in the spleen using both the LDUV and RDUV methods were limited by the low wave amplitude at frequencies above 300 Hz. This might be due to the spleen tissue being somewhat softer than the gelatin and excised myocardium as evident in the estimates of elasticity (μ1) and viscosity (μ2) (Figure 7). Due to the softness of the material, the spleen is more attenuative for shear waves and the waves did not propagate as far, especially at higher frequencies [30].

The in vivo use of the RDUV method in open-chest pigs has been reported by our group [1] and has shown promising results in estimating viscoelasticity of a beating heart. Clinical application of the Shearwave Dispersion Ultrasound Vibrometry (SDUV) method to quantify viscoelasticity of the human heart is a subject of current investigation.

One of the limitations of this method is the inability to use the mechanical actuator for in vivo patient measurements. In vivo open chest studies in porcine left ventricle using a mechanical actuator have been reported by our group [1]. While the focus of this paper is validation of the RDUV approach, future research will be aimed at using a linear array to focus radiation force to excite Lamb and Rayleigh waves and track the motion.

Both the LDUV and RDUV methods have the ability to measure the dispersion velocity at different depths and angles relative to the fiber orientation in the myocardial wall. Values of Lamb and Rayleigh wave velocities through the thickness of the samples were averaged for the purpose of this study. The affect of anisotropy due to fiber orientation and nonuniform boundaries are beyond the score of this study.

Radiation force can be weak in heart, especially when the ultrasound has to propagate long distances through the intercostal space. The spleen is around 2–8 cm away from the skin surface (depending on the size of the patient) and the radiation force may be weak and the wave propagation may be difficult in larger patients due to amplitude attenuation. The smallest displacement measurable by our method in an ex vivo setting is on the order of 100–200 nm [31]. While the threshold is likely to be higher for in vivo studies, we do not expect a drastic change. While the physiological motion of a beating heart is likely to present unique problems in exciting the waves, the surface excitation of the RDUV method may be less sensitive since it does require focusing of the radiation force in the middle of the myocardial wall.

CONCLUSION

Lamb and Rayleigh wave dispersion equations for a viscoelastic plate submerged in a nonviscous fluid of similar density are presented. The two dispersion equations show analytical convergence at higher frequencies. Experimental convergence was demonstrated in a finite element analysis of a viscoelastic plate in a fluid. Results showing similar dispersion velocities in gelatin plates and excised porcine spleen and left ventricular free-wall myocardium samples using surface (Rayleigh) and body (Lamb) wave excitation are presented. The Lamb wave dispersion equation was fitted to the experimental dispersion data obtained using surface (Rayleigh) and body (Lamb) wave excitation to estimate elasticity (μ1) and viscosity (μ2) of the samples. The results suggest that surface and body wave excitation produce similar dispersion velocities and can be used to obtain Lamb wave velocities and estimate elasticity (μ1) and viscosity (μ2) of left-ventricular myocardium.

References

- 1.Pislaru C, Urban MW, Nenadic I, Greenleaf JF. Shearwave dispersion ultrasound vibrometry applied to in vivo myocardium. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2009;2009:2891–4. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5333114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nenadic IZ, Urban MW, Mitchell SA, Greenleaf JF. Lamb wave dispersion ultrasound vibrometry (LDUV) method for quantifying mechanical properties of viscoelastic solids. Phys Med Biol. 2011 Apr 7;56:2245–64. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/7/021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zile MR, Brutsaert DL. New concepts in diastolic dysfunction and diastolic heart failure: Part I: diagnosis, prognosis, and measurements of diastolic function. Circulation. 2002 Mar 19;105:1387–93. doi: 10.1161/hc1102.105289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Burnett JC, Jr, Mahoney DW, Bailey KR, Rodeheffer RJ. Burden of systolic and diastolic ventricular dysfunction in the community: appreciating the scope of the heart failure epidemic. Jama. 2003 Jan 8;289:194–202. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maeder MT, Kaye DM. Heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Mar 17;53:905–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.A. H. Association. American Heart Association. Vol. 2010. Dalas, Texas: American Heart Association; Heart Disease & Stroke Statistics - 2010 Update. p. American Heart Association. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konofagou EE, Luo J, Saluja D, Cervantes DO, Coromilas J, Fujikura K. Noninvasive electromechanical wave imaging and conduction-relevant velocity estimation in vivo. Ultrasonics. 2010 Feb;50:208–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konofagou EE, D’Hooge J, Ophir J. Myocardial elastography--a feasibility study in vivo. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2002 Apr;28:475–82. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(02)00488-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanai H. Propagation of spontaneously actuated pulsive vibration in human heart wall and in vivo viscoelasticity estimation. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2005 Nov;52:1931–42. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2005.1561662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu SJ, Bouchard RR, Dumont DM, Wolf PD, Trahey GE. In vivo assessment of myocardial stiffness with acoustic radiation force impulse imaging. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2007 Nov;33:1706–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couade M, Pernot M, Messas E, Bel A, Ba M, Hagege A, Fink M, Tanter M. In vivo quantitative mapping of myocardial stiffening and transmural anisotropy during the cardiac cycle. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2011 Feb;30:295–305. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2010.2076829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouchard RR, Hsu SJ, Wolf PD, Trahey GE. In vivo cardiac, acoustic-radiation-force-driven, shear wave velocimetry. Ultrason Imaging. 2009 Jul;31:201–13. doi: 10.1177/016173460903100305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sack I, Rump J, Elgeti T, Samani A, Braun J. MR elastography of the human heart: noninvasive assessment of myocardial elasticity changes by shear wave amplitude variations. Magn Reson Med. 2009 Mar;61:668–77. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolipaka A, Araoz PA, McGee KP, Manduca A, Ehman RL. Magnetic resonance elastography as a method for the assessment of effective myocardial stiffness throughout the cardiac cycle. Magn Reson Med. 2010 Sep;64:862–70. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elgeti T, Laule M, Kaufels N, Schnorr J, Hamm B, Samani A, Braun J, Sack I. Cardiac MR elastography: comparison with left ventricular pressure measurement. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2009;11:44. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-11-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin M, Chen J, Glaser KJ, Talwalkar JA, Ehman RL. Abdominal magnetic resonance elastography. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2009 Apr;20:79–87. doi: 10.1097/RMR.0b013e3181c4737e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talwalkar JA, Yin M, Venkatesh S, Rossman PJ, Grimm RC, Manduca A, Romano A, Kamath PS, Ehman RL. Feasibility of in vivo MR elastographic splenic stiffness measurements in the assessment of portal hypertension. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009 Jul;193:122–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bota S, Sporea I, Sirli R, Popescu A, Danila M, Sendroiu M, Focsa M. Spleen assessment by Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse Elastography (ARFI) for prediction of liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Med Ultrason. 2010 Sep;12:213–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salameh N, Peeters F, Sinkus R, Abarca-Quinones J, Annet L, Ter Beek LC, Leclercq I, Van Beers BE. Hepatic viscoelastic parameters measured with MR elastography: correlations with quantitative analysis of liver fibrosis in the rat. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007 Oct;26:956–62. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huwart L, Peeters F, Sinkus R, Annet L, Salameh N, ter Beek LC, Horsmans Y, Van Beers BE. Liver fibrosis: non-invasive assessment with MR elastography. NMR Biomed. 2006 Apr;19:173–9. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmeling TJ, Hettrick DA, Kersten JR, Pagel PS, Warltier DC. Changes in passive but not active mechanical properties predict recovery of function of stunned myocardium. Ann Biomed Eng. 1999 Mar-Apr;27:131–40. doi: 10.1114/1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nightingale KR, Palmeri ML, Nightingale RW, Trahey GE. On the feasibility of remote palpation using acoustic radiation force. J Acoust Soc Am. 2001 Jul;110:625–34. doi: 10.1121/1.1378344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen S, Urban MW, Pislaru C, Kinnick R, Zheng Y, Yao A, Greenleaf JF. Shearwave dispersion ultrasound vibrometry (SDUV) for measuring tissue elasticity and viscosity. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2009 Jan;56:55–62. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2009.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kundu T. Ultrasonic Nondestructive Evaluation. New York: CRC Press; 2003. pp. 1–95. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graff KF. Wave Motion in Elastic Solids. London, UK: Oxford University Press; 1975. pp. 273–310. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Achenbach JD. Wave Propagation in Elastic Solids. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers B. V; 2005. pp. 10–165. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu JY, Popovics JS, Schubert F. Leaky Rayleigh and Scholte waves at the fluid-solid interface subjected to transient point loading. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2004 Oct;116:2101–2110. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerardi FR. Application of Mellin and Hankel Transforms to Networks with Time-Varying Parameters. IRE Trans Circuit Theory. 1959 Jun;CT-6:197–208. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vappou J, Maleke C, Konofagou EE. Quantitative viscoelastic parameters measured by harmonic motion imaging. Phys Med Biol. 2009 Jun 7;54:3579–94. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/11/020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urban MW, Chen S, Greenleaf JF. Error in estimates of tissue material properties from shear wave dispersion ultrasound vibrometry. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2009 Apr;56:748–58. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2009.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Urban MW, Chen S, Greenleaf J. Harmonic motion detection in a vibrating scattering medium. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2008 Sep;55:1956–74. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]