Abstract

Background:

Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) has been employed as a useful technique for the initial diagnosis of soft tissue tumors (STT) as well for the identification of recurrent and metastatic cases.

Aim:

We conducted this study on soft tissue tumors to find the efficacy of FNAC and to finalize the histological diagnosis with immunostains.

Materials and Methods:

The present study was conducted on 126 patients of soft tissue tumors. FNAC and histopathology was performed in all the cases.

Results:

Hundred and five cases (83.3%) were diagnosed as benign and 21 cases (16.7%) as malignant. On FNAC, tumors were divided into six cytomorphological categories i.e. lipomatous, spindle cell, round cell, myxoid, pleomorphic and vascular tumors. Seventeen cases were inconclusive on cytology. In five cases, the type of malignancy was changed on histological examination. There were three false positive and two false negative cases giving a positive predictive value of 97.2 % in terms of malignancy, a sensitivity of 98.1% and a specificity of 96.7%.

Conclusions:

FNAC has a definite role in forming the initial diagnosis of STT, while histopathology with the aid of immunomarkers provides the final diagnosis.

Keywords: Fine needle aspiration cytology, immunostain, soft tissue tumors

Introduction

Soft tissue tumors (STT) are not very common. The ratio of benign to malignant STT is 100:1. In United States sarcomas are diagnosed as 0.8% of invasive malignancies per annum and cause 2% of cancer deaths.[1] Sarcomas form 7-15 % of pediatric malignancies in first year of life.[2] Incidence of STT is difficult to assess because not all benign STTs get biopsied. The cells of origin are varying, so the diagnosis of STT is difficult at times. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) has been employed as a useful technique for the initial diagnosis of STT as well for the identification of recurrent and metastatic cases.[3] Grading of STT is viewed as a categorical system which has possible prognostic capabilities.[4–6] We conducted this study on soft tissue tumors to find the efficacy of FNAC and to finalize the histological diagnosis with immunostains.

Materials and Methods

The present study was conducted on 126 patients of soft tissue tumors for a period of 18 months. The FNAC and histopathological examination of STT was carried out in all the cases. The FNAC was ultrasound guided in four cases with mass in abdomen. The smears were stained with Papanicolaou (Pap) and hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) stains.[7] The paraffin sections of surgically resected specimens were stained with H and E, Reticulin (Reti), Van Gieson (VG), Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) and Phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin (PTAH).[8] Immunohistochemistry (IHC) on paraffin sections was performed in 23 cases. The immunostains included vimentin (Vim), desmin (Des), myosin (Myo), S100, cytokeratin (CK), synaptophysin (Syn), CD34 and Leucocyte common antigen (LCA).[8]

Results

Hundred and twenty six cases of STT were classified according to the cytological and histological diagnosis. On histology, 105 cases (83.3 %) were diagnosed as benign and 21 cases (16.7 %) as malignant.

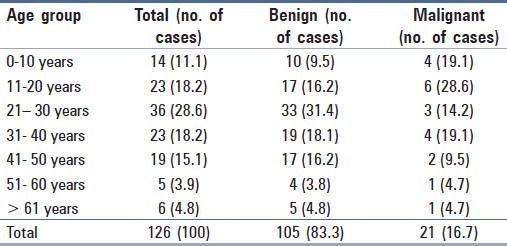

The relative incidence of STTs was 0.26/1000/yr. Most of the STT i.e. 115 cases (91.2%) were distributed between 1st to 5th decades [Table 1]. Out of 126 cases, 81 cases (64.3%) were males and 45 cases (35.7%) were females with a M:F ratio of 1.8:1. The benign STT occurred in 65 (61.9%) males and 40 (38.1 %) females with a M:F ratio of 1.6:1. The malignant STTs were seen in 15 (71.4 %) males and 6 (28.6%) females giving a M:F ratio of 2.5:1. Thus, malignant STTs were seen more commonly in males.

Table 1.

Age distribution of cases of STT in decades

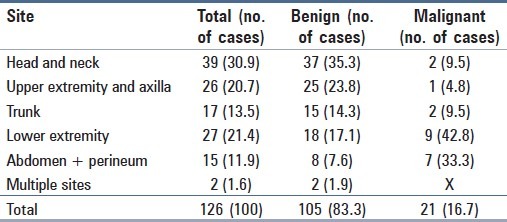

Maximum number of benign STTs i.e. 43 cases (40.9%) were seen in extremities followed by head and neck, 37 cases (35.3%) [Table 2]. Most of them were lipomas and hemangiomas. Malignancies were more common in lower extremities, nine cases (42.8%) and abdomen, seven cases (33.3%). Most common malignant tumors in lower extremity were liposarcomas and fibrosarcomas, while in abdomen, they were leiomyosarcomas. Two cases of STT involving multiple sites were one case each of fibroma and neurofibroma. Size of benign and malignant STTs ranged from 0.3 – 20 cm and 2 – 15 cm, respectively, with not much difference in sizes.

Table 2.

Distribution of cases of STT according to site

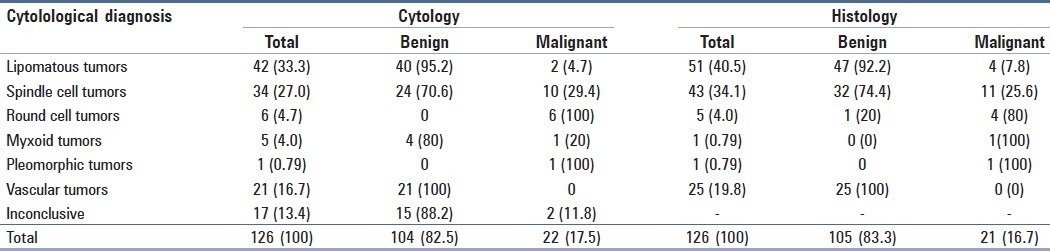

On FNAC smears, 104 cases (82.5 %) were benign and 22 cases (17.5 %) were malignant.

Among the six cytomorphological categories, there were 42 cases (33.3%) of lipomatous tumors, 34 cases (27.0%) of spindle cell tumors, 6 cases (4.7%) of round cell tumors, 5 cases (4.0%) of myxoid tumors, 1 case (0.79%) of pleomorphic tumor and 21 cases (16.7%) of vascular tumors [Table 3].

Table 3.

A comparison of cytological and histopathological diagnosis of STT

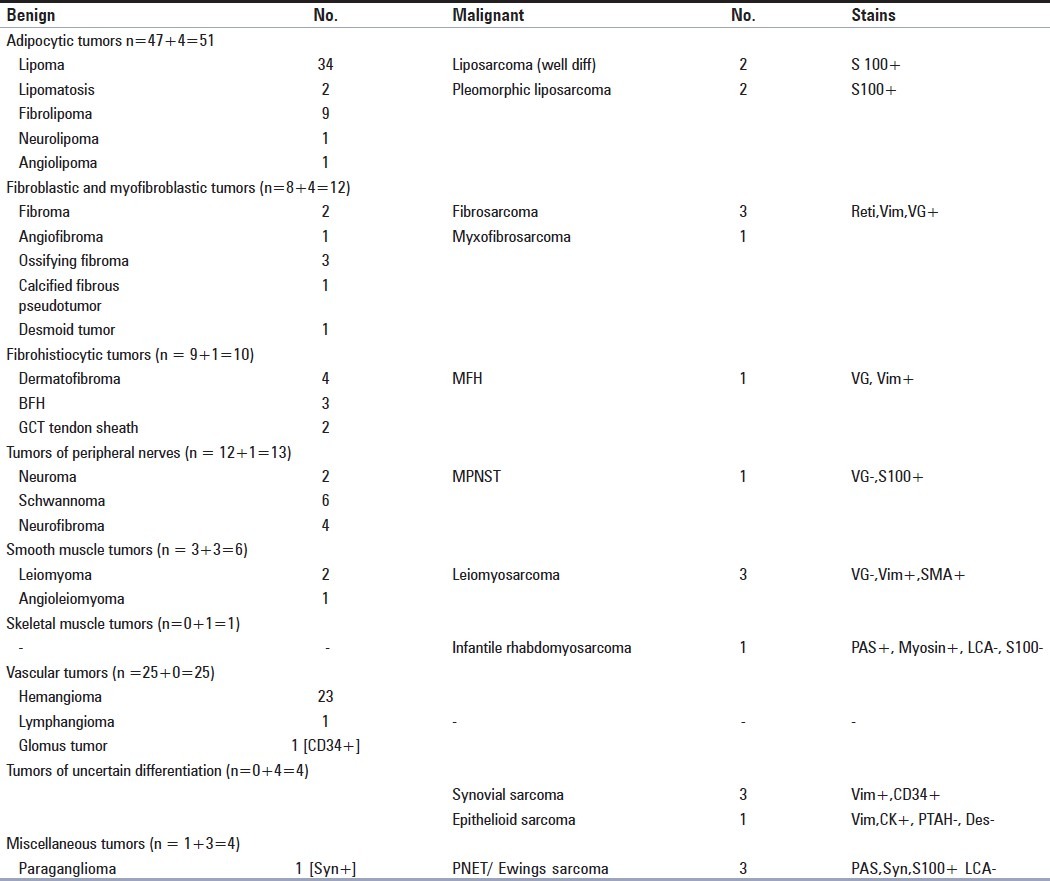

Seventeen cases (13.4%) which were inconclusive on cytology turned out to be benign in 15 cases as lipoma (8 cases), fibroma (1 case), schwannoma (3 cases), hemangioma (3 cases) and malignant in 2 cases as leiomyosarcoma (1 case) and pleomorphic liposarcoma (1 case) on histology [Table 4].

Table 4.

Histopathological diagnosis of soft tissue tumors (n=126)

On cytological diagnosis [Table 3] out of 42 lipomatous tumors, 40 were diagnosed as benign and 2 as malignant. Eight cases which were inconclusive on cytology turned out to be lipoma on histology, while 1 inconclusive case was reported as pleomorphic liposarcoma (S100+) on histology. One case of well differentiated atypical lipomatous tumor was falsely reported as benign lipomatous tumor on cytology due to lack of lipoblasts. Thus, on final histological diagnosis, there were 47 benign and 4 malignant lipomatous tumors [Figure 1].

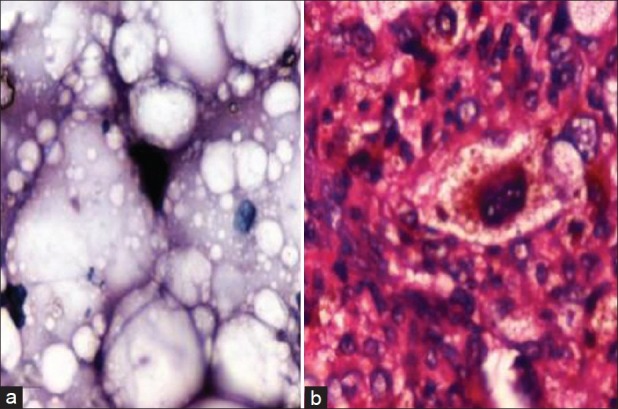

Figure 1.

Pleomorphic liposarcoma (a) Multivacuolated lipocytes, nuclei large hyperchromatic, indented by cytoplasmic vacuoles (FNAC, H and E, ×400) (b) Floret cells and malignant lipocytes (Histo., H and E, ×400)

The next largest category on cytology was spindle cell tumors comprising of 34 (24 benign and 10 malignant) cases. On histology, there were 43 (32 benign and 11 malignant) cases, further sub divided into tumors of fibroblasts [Figure 2] and myofibroblasts (11 cases), fibrohistiocytic tumors (10 cases), tumors of peripheral nerves [Figure 3] (13 cases), tumors of smooth muscle (6 cases) and synovial sarcoma (3 cases). Out of these 43 cases, 5 cases inconclusive on cytology were diagnosed on histology as schwannoma (3 cases), fibroma (1 case) and 1 case of leiomyosarcoma (reti, VG, Vim +). The change in cytological diagnosis on biopsy included 1 case of malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) to benign fibrous histiocytoma (BFH). One case of synovial sarcoma was diagnosed as benign spindle cell tumor due to the presence of spindle cells and blood in smears. On histology, it showed infiltrating margins, pattern of hemangiopericytoma and malignant spindle cells with mitosis [Figure 4]. We found that the most common malignant STTs were spindle cell tumors (11 cases).

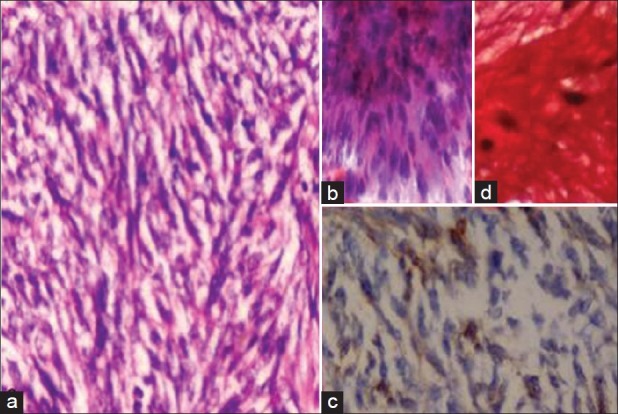

Figure 2.

Fibrosarcoma (a) High cellularity, malignant cells forming herring bone pattern (Hist., H and E, ×400) (b) cellular smear, fascicles of malignant spindle cells (FNAC, H and E, ×400) (c) Vim + (d) VG +

Figure 3.

Schwannoma (a) Loosely arranged spindled vesicular nuclei with pointed ends, fibrillary stroma (FNAC, H and E, ×400) (b) Palisading spindle nuclei, verocay bodies (Histo., H and E, ×200)

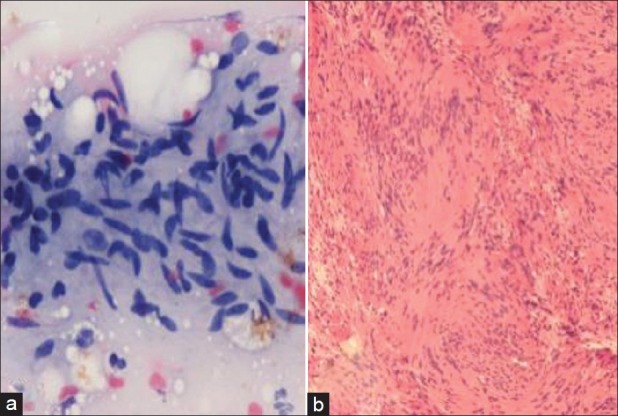

Figure 4.

Synovial sarcoma (a) Cellular smear, round to spindle nuclei, hemorrhagic background (FNAC, H and E, ×400) (b) Slit like vascular spaces surrounded by cells with thick nuclear membrane and high mitotic rate (Histo., H and E, ×400) (c) Vim + (d) CD 34 +

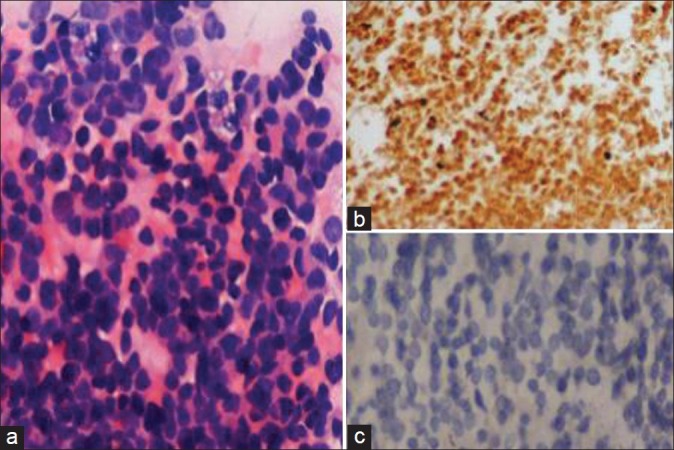

All the six cases of round cell tumors (RCT) were diagnosed as malignant on cytology. On histology, these were Ewing sarcoma/PNET (3 cases) which were PAS+, Syn+, S100+, LCA –ve [Figure 5], infantile rhabdomyosarcoma (1 case) which was PAS + and myosin +. Two cases of RCT with uniform round nuclei were diagnosed as benign lesions on histology as glomus tumor and paraganglioma, 1 case each.

Figure 5.

Ewing's/PNET (a) Cellular smear, loose aggregates of round cells, a few rosettes, finely granular chromatin, minimal cytoplasm (FNAC, H and E, ×400) (b) Syn + (c) LCA – ve

Out of the five (four benign and 1 malignant) myxoid tumors on cytology, four cases which showed myxoid material with spindle cells were neurofibromas on histology. One case in which cytology showed abundant myxoid material with malignant spindle cells was myxofibrosarcoma on histology.

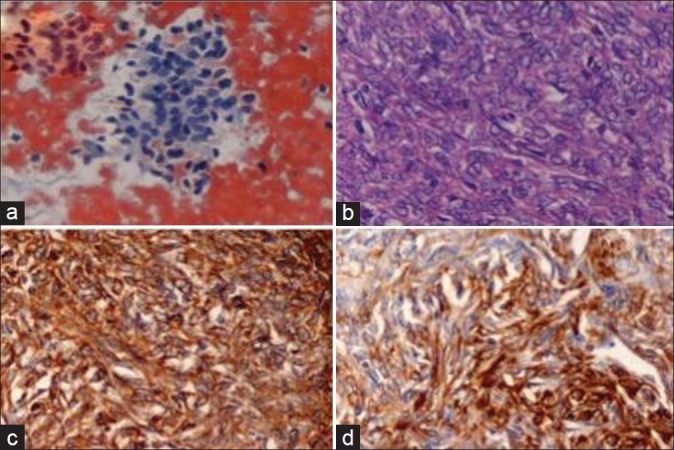

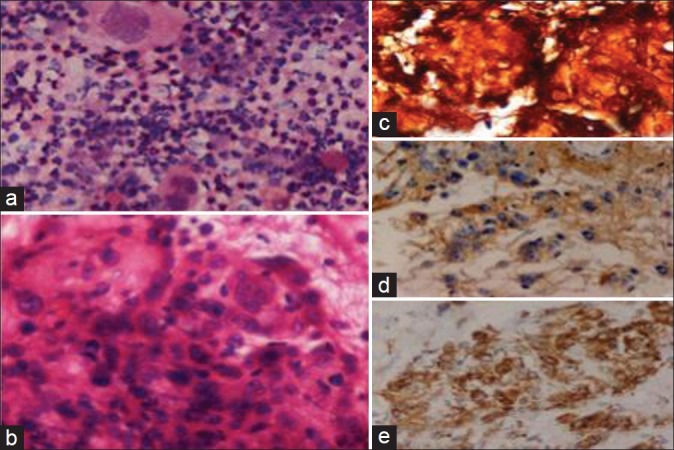

The single case diagnosed as pleomorphic tumor on cytology turned out to be epithelioid sarcoma (Vim+, CK+, Des –ve, PTAH –ve) on histology [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Epithelioid sarcoma (a) Bizarre large pleomorphic cell. (FNAC, H and E, ×400) (b) Flat cells changing to spindle cells, malignant nuclei (Histo., H and E, ×400) (c) Group of flat cells with individual reticulin network (Reti, ×400) (d) CK + (e) Vim +

Out of the 25 vascular tumors on histology, there were 20 cases of hemangioma and 1 case of lymphangioma diagnosed mainly on clinical history and examination as FNAC showed only blood and lymph respectively with a few endothelial cells in occasional cases. Three cases of hemangioma were inconclusive on cytology. The diagnosis of glomus tumor as round cell tumor (1 case) on cytology was corrected on histology.

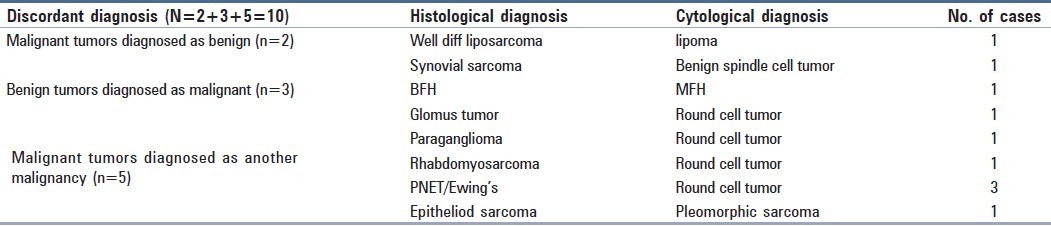

On the basis of FNAC 104 cases (True positive) could be correctly diagnosed out of which 87 were benign and 17 were malignant. There were three false positive cases which were benign diagnosed as malignant and two false negative cases which were malignant diagnosed as benign on cytology and 17 inconclusive cases diagnosed correctly on histology. Five cases of malignancy were diagnosed as another malignancy on cytology [Tables 3 and 5].

Table 5.

Discordant diagnosis (N=2+3+5=10)

Histopathological confirmation of benign and malignant STT gave a positive predictive value of 97.2 % in terms of malignancy, a sensitivity of 98.1% and a specificity of 96.7%.

Discussion

The application of FNAC has lead to reasonably accurate diagnoses of various types of soft tissue tumors in various parts of the body. Complex heterogeneity is a challenging factor in the diagnosis of STTs.

This study was conducted on 126 patients of soft tissue tumors. Hundred and five cases (83.3%) were benign and 21 (16.7%) were malignant. IHC was done in 23 cases to reach the final diagnosis. The results were comparable with the reports of other authors. Bezabih[9] found 82.8% cases (516 / 623) as benign and 17.2% (107 / 623) as malignant. Dey et al.[10] found 83.7% (1135 /1356) cases of benign and 16.3 % (221 / 1356) cases of malignant STT.

Majority of STT in our study were distributed between 1st to 5th decades, 115 cases (91.2%). Ninety six cases (91.4%) of benign STT and 19 cases (90.4%) of malignant STT were also seen in the same range. Nagira et al.[11] in their study on 279 cases of STT reported the mean age of 48 years, while Bezabih[9] found the most common age group for benign tumors as 4th and 5th decades and for malignant tumors, 1st and 2nd decades.

We reported maximum number of STT in extremities, 53 cases (42.1%). Other authors like Bezabih[9] and Nagira et al.[11] also found lower extremity as the most common site of STTs followed by upper extremity.

As in our study, Bezabih[9] also reported lipoma (70.5%) as the most common benign STT and spindle cell tumor as the most common malignant STT (63.6%). Bennert et al[12] in their study of 117 patients found lipoma (69%) as the most common benign STT and MFH (27%) as the most common malignant STT, followed by liposarcoma (13.5%) on core needle biopsy. Nagira et al.[11] reported the most common benign STT as spindle cell (31.5%) followed by lipomatous tumor (14.6%), while the most common malignant STT in their study was pleomorphic cell (35%) followed by round cell tumor (19.3%).

Cytological details of aspiration smears along with clinico-radiological details help in making a diagnosis. Both cytological details including cell types, lipomatous, spindle, round or pleomorphic and the background material like lipomatous, myxoid or metachromatic stromal fragments are indicators of the type of STT on FNAC. We used a similar approach in subtyping the STT on cytology.[3,9–12]

Seventeen cases were reported as inconclusive on FNAC in our study. There were 10 discordant cases. One case of well differentiated liposarcoma was diagnosed as benign lipomatous lesion as only a few foamy cells were aspirated which resembled mature lipocytes. One case of synovial sarcoma was labelled as benign spindle tumor due to presence of only a few spindle cells and blood in the smear. The tumor on histopathology showed infiltrating margins and a pattern of hemangiopericytoma with slit like endothelial lined vascular spaces distributed uniformly in sheets of cells. Cells were plump to spindle with hyperchromatic round nuclei. Mitosis was 5/10 HPF. Tumor was CD 34+ and Vim +. On the other hand, one case of BFH was mislabelled as MFH due to large tumor size of 10 cm and apparently hyperchromatic spindle cells in cartwheel arrangement. On histological examination, the tumor was circumscribed, nuclei were benign and mitosis was not evident. There was no necrosis or myxoid change. Thus, it was diagnosed as BFH. Glomus tumor and paraganglioma were labelled as malignant round cell tumors on FNAC smears as they appeared as clusters of round dark nuclei in smears suggesting malignancy. On histology, the glomus tumor showed well circumscribed tumor of 1.5 cm with well demarcated nests of uniform round nuclei with minimal cytoplasm (CD 34 +) separated by fibrous septa. The paraganglioma showed cell ball arrangement of tumor cells (Syn +) separated by fine vascularized septa and non infiltrating tumor margins.

Five cases diagnosed as malignant on cytology were changed to another type of malignancy on histopathological examination. Four of these were round cell tumors which required immuno markers for final diagnosis. They included infantile rhabdomyosarcoma (PAS+, Myo +) (1 case) and PNET (PAS+, Syn +, S100+) (3 cases). One case of epithelioid sarcoma was labelled as pleomorphic sarcoma on cytology as the smear showed pleomorphic cells and lacked flat epithelial and spindle cells. Histopathology showed flat epithelial cells changing to spindle cells, malignant nuclei with nucleoli and increased and atypical mitosis. Reticulin network could be demonstrated around each cell without any organoid formation. The cells were Vim + and CK+.

Immunomarkers were used in 23 cases which helped in confirming the diagnosis especially in round cell and spindle cell tumors.

In our study, there were 3 FP, 2 FN cases and 17 inconclusive cases on FNAC giving a positive predictive value of 97.2% in terms of malignancy, a sensitivity of 98.1% and a specificity of 96.7%. A study on 517 STT aspirates by Akerman et al.[13] revealed a 2.9% false positive rate, the subsequent studies by Wakely et al,[14] and by Kilpatrick et al,[15] yielded a single case of false negativity and nil false positivity. This was in contrast to a study by Nagira et al,[11] who identified higher figures for false positivity and false negativity with a specificity of 92% and sensitivity of 97%. Wakely et al,[14] reported 100% sensitivity and 97% specificity in STT diagnosis with FNAC. Layfield et al,[16] achieved 95% sensitivity and specificity while dealing with these lesions.

Thus, we conclude that FNAC has a definite role in forming the initial diagnosis of STT, while histopathology with the aid of immunomarkers provides the final diagnosis leading to effective management taking into consideration the behavior of the tumor.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Rosenberg AE. Bones, joints, and soft tissue tumors. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, editors. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. 7th ed. New Delhi: Saunders, Elsevier; 2004. p. 1316. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orbach D, Rey A, Oberlin A, de Toledo J Sanchez, Terrier-Lacombe MJ, van Unnik A, et al. Soft tissue sarcoma or malignant mesenchymal tumors in the first year of life: Experience of International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP), Malignant Mesenchymal Tumor Committee. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4363–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rekhi B, Gorad BD, Kakade AC, Chinoy R. Scope of FNAC in the diagnosis of soft tissue tumors-a study from a tertiary cancer referral center in India. CytoJournal. 2007;4:20. doi: 10.1186/1742-6413-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coindre JM. Grading of soft tissue sarcomas: Review and update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1448–53. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-1448-GOSTSR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmer HE, Mukunyadzi P, Culberth W, Thomas JR. Subgrouping and grading of soft tissue sarcomas by fine needle aspiration cytology: A histopathologic correlation study. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001;24:307–16. doi: 10.1002/dc.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenson OM, Hogh J, Ostgaard SE, Nordentoft AM, Sneppen O. Histopathological grading of soft tissue tumors: Prognostic significance in a prospective study of 278 consecutive cases. J Pathol. 1991;163:19–24. doi: 10.1002/path.1711630105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bales CE. In: Diagnostic cytology and its histopathologic bases. 5th ed. Koss S, Koss LG, Metamed MR, editors. New York: Lippincott; 2005. pp. 1569–634. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bancroft J, Anderson G. In: Theory and practice of histological techniques. 5th ed. Bancroft JD, Gamble M, editors. Philadelphia: Churchil Livingstone; 2003. pp. 85–108. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bezabih M. Cytological diagnosis of soft tissue tumors. Pathologe. 2007:368–76. S:28. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dey P, Mallik MK, Gupta SK, Vasishta RK. Role of fine needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of soft tissue tumors and tumor like lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 1996;15:23–32. doi: 10.1046/j.0956-5507.2003.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagira K, Yamamoto T, Akisue T, Marui T, Hitora T, Nakatani T, et al. Reliability of fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the initial diagnosis of soft-tissue lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;27:354–61. doi: 10.1002/dc.10200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennert KW, Abdul Karim FW. Fine needle aspiration vs.core needle biopsy of soft tissue tumors. A comparison. Acta Cytol. 1994;38:381–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akerman M, Rydholm A, Persson BM. Aspiration cytology of soft-tissue tumors. The 10-year experience at an orthopedic oncology center. Cytopathology. 2007;18:234–40. doi: 10.3109/17453678508994359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakely PE, Kneisl JS. Soft tissue aspiration cytopathology. Cancer. 2000;90:292–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilpatrick SE, Geisinger KR. Soft tissue sarcomas: The utility and limitation of fine needle aspiration biopsy. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;110:50–68. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/110.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Layfield LJ, Anders KH, Glasgow BJ, Mira JM. Fine needle aspiration of primary soft-tissue tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110:420–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]