Two patients aged 50 years and 49 years, presented with worsening renal function at 4 months and 10½ months respectively, following renal transplant. Both cases were on triple immunosuppressants including tacrolimus, azathioprine and steroids. We received urine samples from both patients to rule out possible viral infection. Serologic tests for cytomegalovirus (CMV) and adenovirus antigens were negative in both cases.

Cytospin smears were prepared from fresh urine samples, fixed in alcohol and stained with Papanicolaou stain.

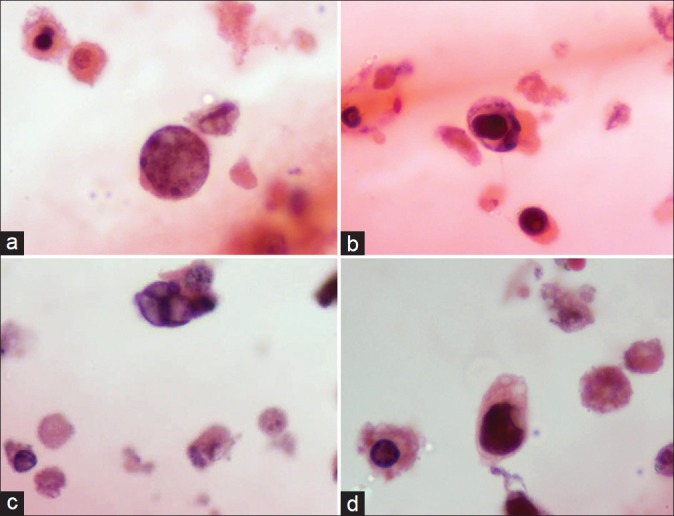

The cytospin smears in both cases showed degenerating epithelial cells, enlarged cells with high nuclear: cytoplasmic ratio showing peripheral clumped chromatin, intranuclear smudgy, groundglass and owl eye-like viral inclusions surrounded by incomplete halo in a clean background [Figure 1]. Both our cases showed more than 10 decoy cells/cytospin smear (i.e. score 3+). However, cytoplasmic inclusions were absent.

Figure 1.

A variety of ‘Decoy’ cells seen in cytospin smears: (a) type 1 inclusion; (b) type 2 inclusion; (c) type 3 inclusion; (d) type 4 inclusion. Also note the cytoplasmic fragments (cytolysis) in the background (Pap, ×1000)

Renal biopsies performed simultaneously for both the cases showed interstitial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation, marked tubular epithelial cell lysis and focal tubular atrophy. No granulomas, interstitial hemorrhage, necrosis (adenovirus nephritis) or endothelial/epithelial ‘owl eye’ inclusions (CMV nephritis) were seen.

Based on these findings and the current clinical setting, urine cytology was reported as positive for high number of “Decoy cells”. In both cases, tacrolimus and azathioprine immunosuppression was reduced. One of the patients succumbed to multiple infections subsequently. The other patient had one episode of reinfection and is currently on regular follow-up.

Polyoma virus (PV) infection is being increasingly recognized as a cause of renal allograft dysfunction. Association with high intensity of immune suppression, especially with tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil or sirolimus has been observed.[1]

Polyoma interstitial nephritis includes an early infection of collecting ducts followed by cytolytic changes and tubular destruction. Evidence of tubular injury in the form of apoptosis, cell drop out, desquamation can be seen. These desquamated cells having the intranuclear viral inclusions, better described as “Decoy cells” can be easily seen on urine cytology. Although light microscopy findings are definitive in most cases, further evaluation by immunohistochemistry (IHC), electron microscopy or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may be necessary for confirmation.[2]

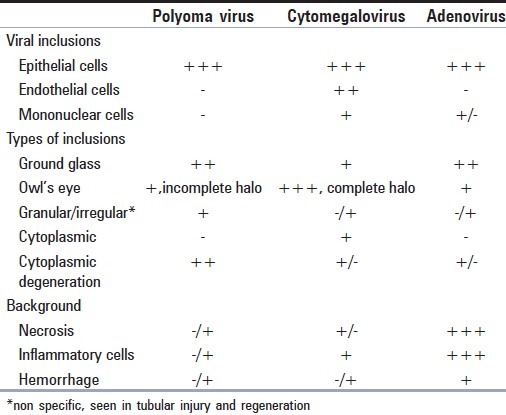

Four morphological types of “Decoy cells” have been described in literature:[3] Type 1- classic decoy cells characterized by large, homogenous, amorphous ground-glass like intranuclear inclusion bodies and a condensed rim of chromatin; Type 2- granular intranuclear inclusions surrounded by a clear halo, i.e., cytomegalovirus (CMV)-like; Type 3- multinucleated decoy cells with granular chromatin; Type 4- vesicular nuclei with clumped chromatin and nucleoli. These inclusions may appear morphologically similar to CMV and adenoviral inclusions. However, trivial morphologic differences do exist which lend a hand to tell them apart [Table 1].

Table 1.

“Decoy cells” may also be mistaken for malignant cells. Lack of coarse chromatin, nuclear membrane irregularity and correlation with cystoscopy findings and clinical scenario are critical to differentiate them. Decoy – like cells can also be seen in tubular injury and regeneration.

Presence of a clear halo around nuclear inclusion along with identification of concurrent cytoplasmic inclusion is a helpful clue to diagnose CMV infection. Severe cytoplasmic degeneration characteristic of polyoma infection; when present, serves as another useful morphologic clue. The urine samples can be classified semiquantitatively as: 1-4 infected cells per cytospin (1+), 5-10 infected cells per cytospin (2+), 11 infected cells per cytospin, but still representing a minority of the total cells in sediment (3+), and too many infected cells to count representing the majority of the cells in the sediment (4+).[5] Urine with large numbers of decoy cells (>10/cytospin), inflammatory sediments and biopsy proven PVN have been noted to have significantly greater decay in renal function than patients with no evidence of PVN.[2]

Geramizadeh et al.,[6] observed that despite a low positive predictive value of decoy cells in urine, its absence has a negative predictive value of 100%, as almost all patients who did not have decoy cells had normal renal function. They further elaborated that presence of decoy cells along with high creatinine levels is a better indicator of virus presence. To conclude, routine urine cytology of post renal transplant patients with worsening renal function is a useful screening procedure to rule out PV reactivation, before ascertaining transplant rejection. Its cost effectiveness in addition to the short processing time makes it an invaluable tool in the evaluation of transplant recipients with symptoms suggestive of graft rejection.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Meehan SM, Kadambi PV, Manaligod JR, Williams JW, Josephson MA, Javaid B. Polyoma virus infection of renal allografts: relationships of the distribution of viral infection, tubulointerstitial inflammation, and fibrosis suggesting viral interstitial nephritis in untreated disease. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:1256–64. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drachenberg CB, Beskow CO, Cangro CB, Bourquin PM, Simsir A, Fink J, et al. Human polyomavirus in renal allograft biopsies: Morphological findings and correlation with urine cytology. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:970–7. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colvin RB, Nickeleit V. Renal transplant pathology. In: Jennet JC, Olson JL, Schwartz, Silva FG, editors. Heptinstall's Pathology of the kidney. 6th ed. Philadelphia: William and Wilkins; 2007. pp. 1441–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asim M, Lopez AC, Nickeleit V. Adenovirus infection of a renal allograft. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:696–701. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drachenberg RC, Drachenberg CB, Papadimitriou JC. Morphological spectrum of polyoma virus disease in renal allografts: diagnostic accuracy of urine cytology. Am J Transplant. 2001;1:373–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geramizadeh B, Roozbeh J, Hosseini M, Salahi H. Urine cytology: useful screening method for polyoma virus nephropathy in renal transplant patients. IJMS. 2006;31:109–11. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.08.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]