Abstract

Background:

The furosemide drip (FD), in addition to improving volume overload respiratory failure, has been used to decrease fluid in attempts to decrease intra-abdominal and abdominal wall volumes to facilitate fascial closure. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the FD and the associated rate of primary fascial closure following trauma damage control laparotomy (DCL).

Materials and Methods:

From January 2004 to September 2008, a retrospective review from a single institution Trauma Registry of the American College of Surgeons dataset was performed. All DCLs greater than 24 h who had a length of stay for 3 or more days were identified. The study group (FD+) and control group (FD-) were compared. Demographic data including age, sex, probability of survival, red blood cell transfusions, initial lactate, and mortality were collected. Primary outcomes included primary fascial closure and primary fascial closure within 7 days. Secondary outcomes included total ventilator days and LOS.

Results:

A total of 139 patients met inclusion criteria: 25 FD+ and 114 FD-. The 25 FD+ patients received the drug at a median 4 days post DCL. Demographic differences between the groups were not significantly different, except that initial lactate was higher for FD- (1.7 vs 4.0; P=0.03). No differences were noted between groups regarding successful primary fascial closure (FD+ 68.4% vs FD- 64.0%; P=0.669), or closure within 7 days (FD+13.2% vs FD- 28.0%; P=0.066) of original DCL. FD+ patients suffered more open abdomen days (4 [2-7] vs 2 [1-4]; P=0.001). FD+ did not demonstrate an association with primary fascial closure [Odds ratio (OR) 1.5, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.260-8.307; P=0.663]. FD+ patients had more ventilator days and longer Intensive Care Unit (ICU)/hospital LOS (P<0.01).

Conclusion:

FD use may remove excess volume; however, forced diuresis with an FD is not associated with an increased rate of primary closure after DCL. Further studies are warranted to identify ICU strategies to facilitate fascial closure in DCL.

Keywords: Furosemide drip, open abdomen, primary fascial closure

INTRODUCTION

While primary abdominal wall closure is a standard part of any laparotomy; this may be hazardous or impossible secondary to any of several physiologic and anatomic derangements. Truncating an operation to perform only life-saving procedures while deferring definitive reconstruction illustrates the core concept behind damage control surgery. Damage control laparotomy (DCL) resulting in an open abdomen has been shown to improve outcomes and decrease mortality in trauma patients in extremis.[1] The concept of damage control continues to gain acceptance throughout all surgical specialties as a means of temporizing until physiologic homeostasis can be restored and the definitive operation can be performed safely.

The decision to truncate an abdominal operation and defer definitive reconstruction is made by considering several factors. For trauma patients, common scenarios that are managed with DCL abdominal compartment syndrome include massive hemorrhage with the lethal triad (coagulopathy, hypothermia, and acidosis) and anatomic constraints secondary to visceral edema and poor abdominal wall compliance.[2]

After the patient has been resuscitated and normal physiology restored, plans can be made for definitive reconstruction and delayed primary closure of the abdominal wall, if possible. The technical feasibility of abdominal wall closure is primarily anatomic and is highly dependent on compliance. Several proven surgical and critical care techniques have been suggested to improve abdominal wall closure.[3–8] Therapeutic diuresis with furosemide is a medical treatment option to improve abdominal wall compliance, but has not been well studied. The purpose of this review was to determine the utility of a furosemide drip (FD) on the closure rates of the open abdomen in patients who had undergone DCL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From January 1, 2004, to September 30, 2008, this retrospective cohort study evaluated all trauma patients admitted to a level 1 trauma center at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) and was captured by the Trauma Registry of the American College of Surgeons (TRACS) dataset. Patients met inclusion criteria if they were greater than or equal to 18 years of age, had an open abdomen for more than 24 hours, and had a hospital length of stay that was equal to or exceeded 3 days. These patients were then divided into two groups, those who received a furosemide drip (FD+) and those who did not receive FD (FD-). Typically, the FD was used to remove excess volume as well as an attempt to decrease intra-abdominal and abdominal wall volumes to facilitate fascial closure. However, no protocol exists describing its use in abdominal wall closure. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of VUMC. All data are maintained in a secure, password protected database that is Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant and all patient information are de-identified prior to analysis and reporting.

Demographic data including age, gender, probability of survival based on the Trauma Injury Severity Score (TRISS), Abbreviated Injury Score (AIS) of the abdomen, initial 24-hour red blood cell (RBC) transfusion, Injury Severity Score (ISS), Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), initial lactate, and mortality were collected. Primary outcomes of the study included primary fascial closure by post-injury day seven without the facilitation of mesh products as well as primary closure regardless of time. Secondary outcomes included total ventilator days, intensive care unit length of stay (ICU LOS), hospital length of stay (LOS), and 30-day mortality.

Statistical analysis was conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 18). Statistical significance was defined as a 2-tailed P≤0.05. Continuous data are reported as medians (IQR) and compared using Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical data are reported as proportions and compared using Fisher's exact test. A multivariate logistic regression model was used to explore the relationship between use of infusions and the ability to achieve primary fascial closure. This model also included clinical variables that were considered to represent confounders, and significant at P value <0.2 in univariate analysis.

RESULTS

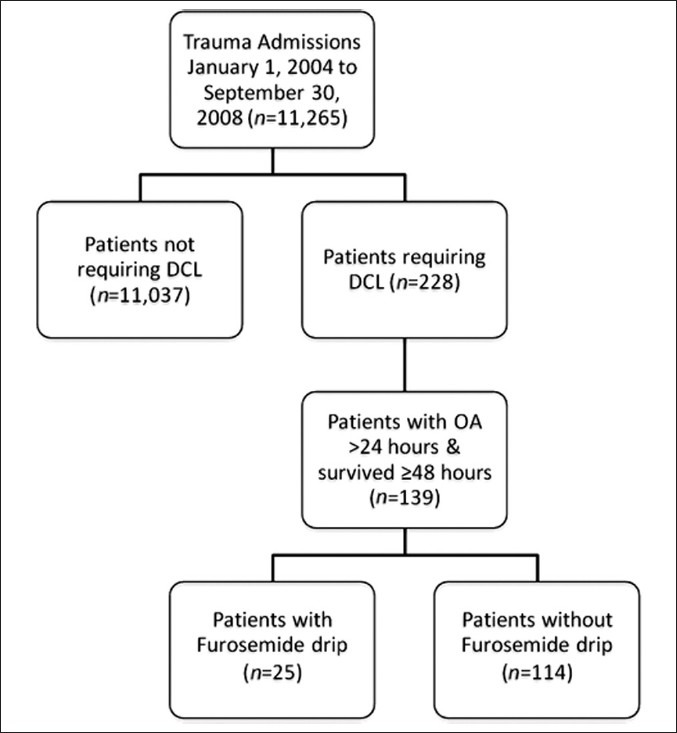

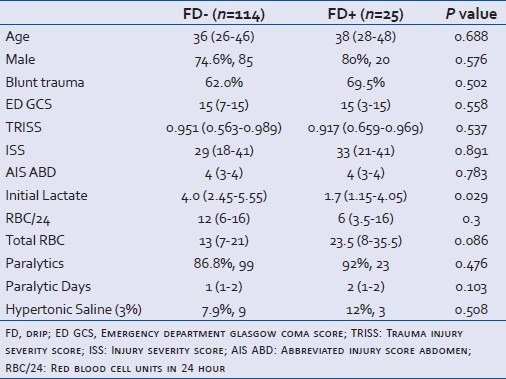

From January 1, 2004, to September 30, 2008, a total of 11,265 patients were admitted to the level I trauma center at VUMC. Of these, 228 patients underwent DCL. In this study, 139 patients met the inclusion criteria, and were divided into two groups. Of the 139 patients fitting inclusion criteria, 25 patients (18%) received a Furosemide Drip (FD+) and 114 (82%) did not (FD-) [Figure 1]. The FD+ patients received the drug with a median administration initiation of 4 days [Interquartile range (IQR 3-8)] post DCL. Table 1 displays demographic and clinical comparisons between the two groups. Only the initial blood lactate level was statistically different between the groups (FD- vs FD+; 4.0 vs 1.7; P=0.029).

Figure 1.

DCL= Damage control laparotomy; OA = Open abdomen

Table 1.

Demographics

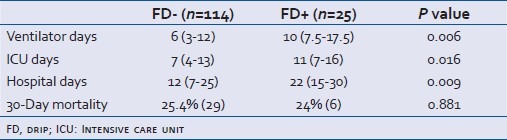

Table 2 shows secondary outcomes as number of days on a ventilator, LOS in ICU and hospital, and 30-day mortality. The use of FD in patients was observed to be greater number of ventilation days (6d vs 10d in FD- vs FD+; 0.006), ICU days (7d vs 11d in FD- vs FD+; 0.016), and overall hospital days (12d vs 22d in FD- vs FD+; 0.009), as compared to those who did not receive the drip. There was no significant difference in 30-day mortality in each of these groups [25.4% (n=29) vs 24% (n=6); P=0.881].

Table 2.

Secondary outcomes

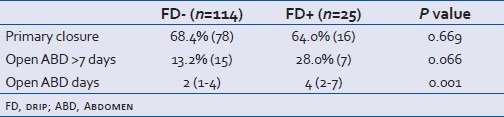

Table 3 shows the primary outcomes of the study. No differences were noted between groups regarding primary fascial closure (FD+ 68.4% vs FD- 64.0%; P=0.669), or closure within 7 days (FD+ 13.2% vs FD- 28.0%; P=0.066) of original DCL. FD+ patients suffered more open abdomen days (4 [2-7] vs 2 [1-4]; P=0.001).

Table 3.

Primary outcomes

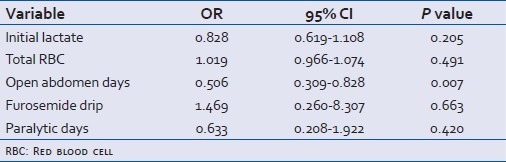

Table 4 shows a multivariate logistic regression model to explore the association between use of an FD, clinical variables that were considered to represent confounders, and the ability to achieve primary fascial closure. Through this model, FD did not demonstrate a significant association [Odds ratio (OR) 1.5, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.260-8.307; P=0.663] with primary fascial closure. The number of open abdomen days did, however, demonstrate a significant odds ratio, predicting an inverse association with primary fascial closure (OR=0.506, 95% CI 0.309-0.828; P=0.007).

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression model

DISCUSSION

DCL has been shown to decrease mortality in the setting of trauma and extremis.[1] However, planned re-exploration of the peritoneal cavity for additional surgical interventions is subsequently warranted.[9] This success has not been without the challenge of closing the open abdomen and preventing subsequent hernia repair and abdominal wall reconstruction.[10–12] Current approaches have focused on finding ways to hasten closure times and allow for early primary repair of the abdominal wall defect. The literature is lacking in ICU protocols to facilitate closure of an open abdomen.

In this study, 139 open abdomen patients, open for >24 hours, and with an LOS >3 days were identified. In 25 patients, the FD was used as part of their ICU care. The use of a FD did not demonstrate a greater likelihood of being able to close the abdomen primarily than those who did not receive the drip. In addition, closure was not accomplished within 7 days of DCL.

In a review of 344 patients and their complications after DCL, Miller et al. revealed that a high rate of wound complications (25%) remains present despite all maneuvers to prevent these issues.[13] Failure to close the open abdomen in a timely manner can be fraught with difficulties, nursing obstacles, and complications leading to ongoing infections, fistulae, malnutrition, physical as well as psychological hardship, and financial burden.[14] Furthermore, delayed primary closure prior to 8 days is associated with the best outcomes for the patient, lowest financial burden, and lower incidence of morbidity.[13] Failure of closure has been attributed to a conglomeration of many factors. Two independent risk factors that have been shown to be associated with failed abdominal closure were the presence of deep surgical site infection and intra-abdominal abscess.[9,15,16] Complications from an ongoing open abdomen include the development of fistulae, intra-abdominal infections, prolongation of systemic inflammatory response syndrome, fluid and electrolyte abnormalities, and nutritional challenges, which put a significant burden to the patient and the healthcare system as a whole.[4,17,18] Controversy remains regarding ICU treatment therapies and methods of closure in these complex patients.

To date, there is no standard method of temporary abdominal closure. Various closure techniques focus on mechanical factors and are designed to prevent loss of domain, thus facilitating earlier closure. The use of the “Bogota bag”, a Wittmann Patch, vacuum-assisted closure (VAC), “sequential fascial closures” from superior and inferior, the use of ties across the wound, and a combination of the aforementioned with VAC use have all been proposed.[3,5,6,8,9] Nevertheless, even with all these different mechanical efforts to hasten closure of the open abdomen, there remains the need to evaluate medical therapies that can contribute to earlier closure.

Optimal medical management of patients with open abdomen is poorly understood. Although limited in their scope, the goals of these therapies would be to minimize abdominal wall tension with sedation and chemical paralysis, utilize judicious fluid and blood product resuscitation, ameliorate the inflammatory cascade, and provide early enteral nutritional support.[4,14,17,19]

Intuitively, one would expect that an FD with its proven efficacy to improving oxygenation and pulmonary status would be beneficial in closing the open abdomen.[18] FD administration to create a diuresis after the patients’ “capillary leak” has been sealed and fluid sequestration is complete has been thought to play a role in volume reduction of the abdominal contents and abdominal wall. Subsequently, the FD has been hypothesized to improve the ability to close the open abdomen. Despite these assumptions, this investigation was unable to demonstrate an associate between FD+ and improved primary fascial closure in patients who underwent DCL.

Inherent limitations to this study include the retrospective study design. Furthermore, this was a small sample size from a single center. There is no current standard for FD utilization for the purpose of facilitating abdominal wall closure, which creates variability of administration. There were variable methods of bedside dressing change schedules and techniques, operating room timing, and methods of primary fascial closure. No endpoints of resuscitation were examined and, subsequently, it is unclear which patients benefit the least or most from FD in the open abdomen setting. In addition, actual quantities of positive or negative fluid balance achieved with the use of FD were not quantified. The findings that the FD use did not aid in earlier primary fascial closure may indicate that the patients, who were receiving FD were more severely injured or critically ill, received a larger fluid resuscitation, or suffered a degree of illness not quantified in the demographics (AIS abdomen, TRISS, and ISS) of this study.

Another limitation is lack of standard furosemide dosing and/or quantification. The FD dose is commonly titrated in our ICUs to a urine output, most often 200 ml/h. This results in a variable furosemide administration, depending on the patient response (range, 5-20 mg/h). Furthermore, our FDs sometimes are initiated with a bolus dose. Although we did not properly quantify furosemide administration, it has a number of actions that may be beneficial, other than diuresis, such as serving as an anti-inflammatory agent or anti-oxidant. It has been noted that furosemide inhibits activated rat peritoneal mast cells.[20–22] Other in vitro and in vivo investigations in Wistar rat models have demonstrated reduction in oxidative stress, suggesting a free radical scavenging effect of furosemide.[23] However, our study was not designed to measure these subtle endpoints with respect to furosemide administration.

In any case, patients who received an FD required a prolonged LOS, ICU, LOS, and ventilator days. However, despite the above-mentioned limitations, this is the largest description of FD use and its effect on closing the open abdomen.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the use of FD may remove excess volume; however, forced diuresis with an FD is not associated with an increased rate of delayed primary closure after DCL. In fact, FD may be associated with worse outcomes and caution should be taken when choosing this therapy in the hope of aiding in the closure of the open abdomen. Future prospective studies are warranted to identify ICU strategies to increase rates of fascial closure in trauma DCL.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors greatly appreciate the support and guidance of John A. Morris, MD and Jose J. Diaz, MD.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Mayur B Patel supported in part by AHRQ Health Services Grant 5T32HS013833-08

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rotondo MF, Schwab CW, McGonigal MD, Phillips GR, 3rd, Fruchterman TM, Kauder DR, et al. ‘Damage control’: An approach for improved survival in exsanguinating penetrating abdominal injury. J Trauma. 1993;35:375–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirshberg A, Walden R. Damage control for abdominal trauma. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:813–20. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70586-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cipolla J, Stawicki SP, Hoff WS, McQuay N, Hoey BA, Wainwright G, et al. A proposed algorithm for managing the open abdomen. Am Surg. 2005;71:202–7. doi: 10.1177/000313480507100305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collier B, Guillamondegui O, Cotton B, Donahue R, Conrad A, Groh K, et al. Feeding the open abdomen. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2007;31:410–5. doi: 10.1177/0148607107031005410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cothren CC, Moore EE, Johnson JL, Moore JB, Burch JM. One hundred percent fascial approximation with sequential abdominal closure of the open abdomen. Am J Surg. 2006;192:238–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koss W, Ho HC, Yu M, Edwards K, Ghows M, Tan A, et al. Preventing loss of domain: A management strategy for closure of the “open abdomen” during the initial hospitalization. J Surg Educ. 2009;66:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reimer MW, Yelle JD, Reitsma B, Doumit G, Allen MA, Bell MS. Management of open abdominal wounds with a dynamic fascial closure system. Can J Surg. 2008;51:209–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinberg JA, George RL, Griffin RL, Stewart AH, Reiff DA, Kerby JD, et al. Closing the open abdomen: improved success with Wittmann Patch staged abdominal closure. J Trauma. 2008;65:345–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31817fa489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barker DE, Green JM, Maxwell RA, Smith PW, Mejia VA, Dart BW, et al. Experience with vacuum-pack temporary abdominal wound closure in 258 trauma and general and vascular surgical patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:784–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poulakidas S, Kowal-Vern A. Component separation technique for abdominal wall reconstruction in burn patients with decompressive laparotomies. J Trauma. 2009;67:1435–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181b5f346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheatham ML, Safcsak K, Llerena LE, Morrow CE, Jr, Block EF. Long-term physical, mental, and functional consequences of abdominal decompression. J Trauma. 2004;56:237–42. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000109858.55483.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen M, Morales R, Jr, Fildes J, Barrett J. Staged reconstruction after gunshot wounds to the abdomen. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:83–92. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200107000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller RS, Morris JA, Jr, Diaz JJ, Jr, Herring MB, May AK. Complications after 344 damage-control open celiotomies. J Trauma. 2005;59:1365–71. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196004.49422.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ivatury RR. Update on open abdomen management: Achievements and challenges. World J Surg. 2009;33:1150–3. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teixeira PG, Salim A, Inaba K, Brown C, Browder T, Margulies D, et al. A prospective look at the current state of open abdomens. Am Surg. 2008;74:891–7. doi: 10.1177/000313480807401002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vogel TR, Diaz JJ, Miller RS, May AK, Guillamondegui OD, Guy JS, et al. The open abdomen in trauma: Do infectious complications affect primary abdominal closure? Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2006;7:433–41. doi: 10.1089/sur.2006.7.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheatham ML, Safcsak K, Brzezinski SJ, Lube MW. Nitrogen balance, protein loss, and the open abdomen. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:127–31. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000250390.49380.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin GS, Moss M, Wheeler AP, Mealer M, Morris JA, Bernard GR. A randomized, controlled trial of furosemide with or without albumin in hypoproteinemic patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1681–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000171539.47006.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malbrain ML, De laet I, Cheatham M. Consensus conference definitions and recommendations on intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) and the abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS)-the long road to the final publications, how did we get there? Acta Clin Belg Suppl. 2007:44–59. doi: 10.1179/acb.2007.62.s1.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stenton GR, Chow SM, Lau HY. Inhibition of rat peritoneal mast cell exocytosis by frusemide: A comparison with disodium cromoglycate. Life Sci. 1998;62:PL49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)01107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer G, Doppierio S, Vallin P, Daffonchio L. Effect of frusemide on Cl- channel in rat peritoneal mast cells. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:2461–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09122461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stenton GR, Lau HY. Inhibition of rat peritoneal mast cell exocytosis by frusemide: A study with different secretagogues. Inflamm Res. 1996;45:508–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02311087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lahet JJ, Lenfant F, Courderot-Masuyer C, Ecarnot-Laubriet E, Vergely C, Durnet-Archeray MJ, et al. In vivo and in vitro antioxidant properties of furosemide. Life Sci. 2003;73:1075–82. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00382-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]