Abstract

Background:

There are studies to prove the role of amylase and lipase estimation as a screening diagnostic tool to detect diseases apart from acute pancreatitis. However, there is sparse literature on the role of serum and urine amylase, lipase levels, etc to help predict the specific intra-abdominal injury after blunt trauma abdomen (BTA).

Aim:

To elucidate the significance of elevation in the levels of amylase and lipase in serum and urine samples as reliable parameters for accurate diagnosis and management of blunt trauma to the abdomen.

Materials and Methods:

A prospective analysis was done on the trauma patients admitted in Jai Prakash Narayan Apex Trauma Center, AIIMS, with blunt abdomen trauma injuries over a period of six months. Blood and urine samples were collected on days 1, 3, and 5 of admission for the estimation of amylase and lipase, liver function tests, serum bicarbonates, urine routine microscopy for red blood cells, and complete hemogram. Clinical details such as time elapsed from injury to admission, type of injury, trauma score, and hypotension were noted. Patients were divided into groups according to the single or multiple organs injured and according to their hospital outcome (dead/discharged). Wilcoxon's Rank sum or Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to compare median values in two/three groups. Data analysis was performed using STATA 11.0 statistical software.

Results:

A total of 55 patients with median age 26 (range, 6-80) years, were enrolled in the study. Of these, 80% were males. Surgery was required for 20% of the patients. Out of 55 patients, 42 had isolated single organ injury [liver or spleen or gastrointestinal tract (GIT) or kidney]. Patients with pancreatic injury were excluded. In patients who suffered liver injuries, urine lipase levels on day 1, urine lipase/amylase ratio along with aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) on days 1, 3, and 5, were found to be significant. Day 1 serum amylase, AST, ALT, hemoglobin, and hematocrit levels were found significant in patients who had spleen injury. Serum amylase levels on day 5 and ALP on day 3 were significant in patients who had GIT injury. Urine amylase levels on day 5 were found to be statistically significant in patients who had kidney injury. In patients with isolated organ injury to the liver or spleen, the levels of urine amylase were elevated on day 1 and gradually decreased on days 3 and 5, whereas in patients with injury to GIT, the urine amylase levels were observed to gradually increase on days 3 and 5.

Conclusion:

Although amylase and lipase levels in the serum and urine are not cost-effective clinical tools for routine diagnosis of extra-pancreatic abdominal injuries in BTA, but when coupled with other laboratory tests such as liver enzymes, they may be significant in predicting specific intra-abdominal injury.

Keywords: Amylase, blunt trauma abdomen, lipase

INTRODUCTION

Trauma continues to be the leading cause of morbidity and mortality, with blunt trauma accounting for the majority of injuries. Evaluation and management of patients with blunt abdominal trauma in the emergency room remains a challenge for emergency physicians. The spectrum of injury may vary from simple to catastrophic events and proper assessment and diagnosis become important in such settings. Various diagnostic modalities have been studied in great detail regarding how they help in the initial management of patients with blunt trauma abdomen (BTA). In the non-invasive tests category, the role of computed tomography (CT), ultrasonography (USG), and focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) scans are already established.[1–3] Till date the function of laboratory tests in the initial assessment and subsequent management of these patients with blunt trauma is controversial. An increase in serum amylase and lipase can be caused by a broad range of conditions in the trauma patient population, which has been associated with pancreatic, hollow viscous, facial, and severe brain injuries.[4] Apart from the pancreas, many different organs contain enzymes with lipolytic activity. Most of these organs such as tongue, esophagus, gastroesophageal junction, various sites of the stomach, duodenum, small bowel, and liver belong to the gastrointestinal tract.[5] Many studies have supported the usefulness of laboratory evaluation in the management of BTA. The serum amylase level has been of interest as a parameter for diagnosis of traumatic injury to the pancreas.[6,7]

However, some studies have found these to be neither sensitive nor specific for diagnosis. Hence, in this regard, experience is limited with the laboratory evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma patients, especially with serum and urine samples, for lipase and amylase levels. The aim of our study was to determine the efficacy of amylase and lipase levels in the diagnosis and management of BTA patients. This study was designed to elucidate the significance of increase in amylase and lipase levels in serum and urine samples as reliable parameters for accurate diagnosis and management of BTA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We performed a prospective analysis of all patients with blunt trauma; we documented laboratory records of days 1, 3, and 5 of admission along with clinical details. Laboratory analysis was done to estimate the amylase and lipase levels in serum and urine samples. Liver function tests, serum bicarbonates, urine routine microscopy for red blood cells (RBCs) and complete hemogram was also performed. During the period from September 2009 to February 2010, all BTA patients presenting at the outpatient department of trauma center were enrolled in the study. Patients with additional conditions such as intestinal obstruction, diabetic ketoacidosis, mesenteric ischemia, peptic ulcer disease, small/large bowel obstruction, acute/chronic cholecystitis, patients having acute abdomen due to strangulated hernia, testicular pathology, and gynecological pathology, were excluded from the study. BTA patients with injury to pancreas were also excluded to assess whether these elevations are due to other intra-abdominal injuries.

Clinical details such as time taken for admission after injury, mode and type of injury, trauma scores, and hypotension were recorded on the day of admission. Revised trauma score was calculated, from the first set of data obtained on the patient, and consisted of Glasgow Coma Scale, systolic blood pressure, and respiratory rate recorded at the time of admission. Revised Trauma Score is a physiological scoring system, with high inter-rater reliability and demonstrated accuracy in predicting death. Approval from the institute ethics committee was procured, before instigating the study.

Sample collection and processing

Routine blood and urine samples were collected on days 1, 3, and 5 of admission for amylase and lipase, and other laboratory investigations, after obtaining an informed consent from the patients. For biochemical analysis, 2 ml of venous blood was collected in a plain gel vial tube and serum was separated by centrifugation and analyzed using a fully automated Beckman Coulter Synchron CX9 biochemistry analyzer. The 2-ml venous blood sample was collected in disposable Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid (EDTA) tubes, for estimation of basic hemogram parameters using a fully automated hematology analyzer, Sysmex XE 2100. Platelet count was performed by an automated method and was counterchecked on the slides prepared by Leishman stain.

Data analysis

Data were recorded on a predesigned proforma and managed on an excel spreadsheet. Quantitative variables were assessed for approximate normal distribution. Some quantitative variables were summarized by median (range), as these were not normally distributed. Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare median values between present and absent, for each of the injury on each of the follow-ups on admission. BTA patients were divided into groups according to the isolated organ injured, single or multiple organs injured, and their outcome (dead/discharged). Quantitative variables normally distributed were summarized as mean±SD. Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to compare median values in two/three groups. Categorical data were analyzed by chi-square test or Fischer's exact test. Data analysis was performed using STATA 11.0 (Stata Corp, TX, USA) statistical software. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

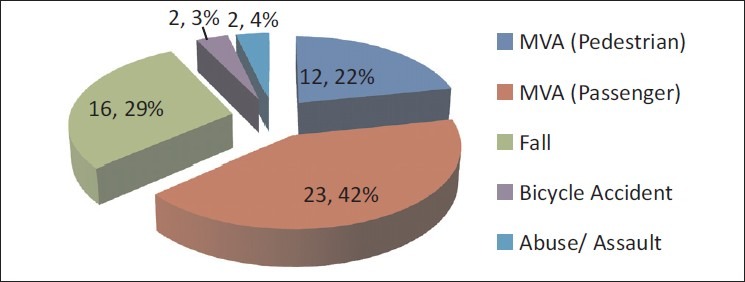

During the study period, 2,505 patients were admitted in the hospital. After applying the exclusion criteria of the study, a total of 55 patients, 11 (20%) females and 44 (80%) males, were enrolled, with median age being 26 (6-80) years. Of the total blunt trauma patients, 29% were below the age of 18 years. A total of 23 patients suffered from trauma due to motor vehicle accident, and only 2 due to assault [Figure 1]. The time elapsed from injury to admission was more than 6 hours in 37 (67.2%) patients. Surgery was required for 11 (20%) patients [Table 1]. At the time of admission, 20 patients (36.4%) were found to have hypotension. Based on the clinical diagnosis done at the time of admission, abdominal abrasion/contusion was seen in 13 (23.6%) patients, blood was observed in the nasogastric tube placed for feeding, administering drugs, or other oral agents in 3 (5.4%) patients. Rectal bleeding was observed in all blunt trauma patients enrolled in this study. Emesis was recorded in 12 (21.8%) patients. The average length of stay was observed to be 12.8 (3-90) days.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of injury in patients with blunt trauma abdomen

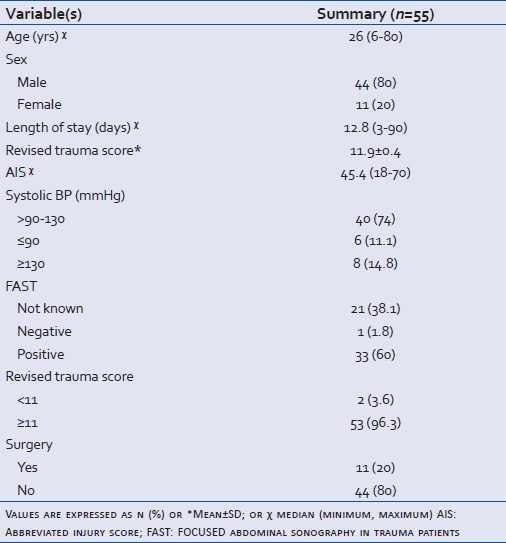

Table 1.

Blunt trauma abdomen patient demographics

A revised trauma score (Mean±SD) was calculated, with the mean among the study population being 11.87±0.4. A more specific and sensitive diagnosis was accomplished on the basis of FAST results for all patients and USG abdomen for 60% of the patients. Although FAST and USG findings were informative, CT scan (chest and abdomen) was done for 14 patients. On the basis of the final diagnosis achieved by all diagnostic tools, the patients were categorized by the location of injury and by isolated or multiple organs injured.

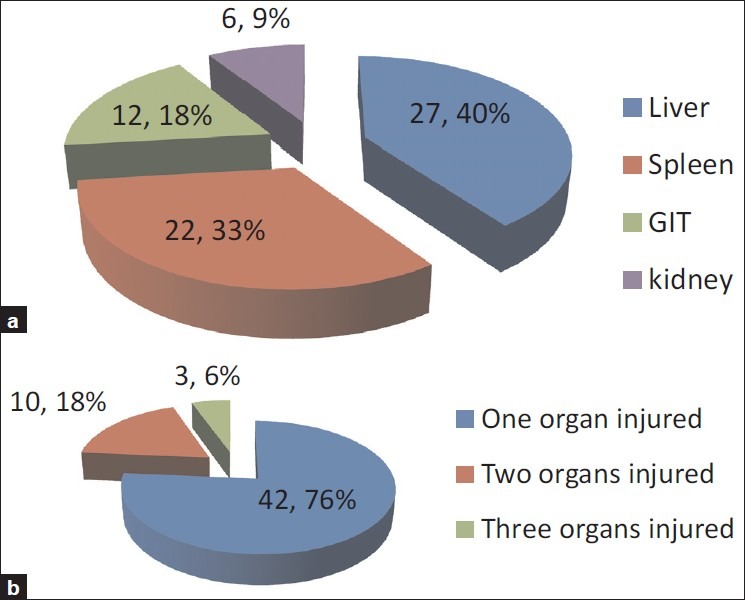

Intra-abdominal injury was present in 52 (94.5%) patients and absent in 3 (5.5%) patients. Of 55 BTA patients, 42 (76.3%) had isolated single organ injury, ie, 17 with liver injury, 15 with spleen injury, 8 with injury to the gastrointestinal tract, and 2 with kidney laceration [Figure 2a]. In 13 (21.0%) patients, more than one abdominal organ was injured, among whom 10 had any two organs injured and only three had injury in any three organs [Figure 2b]. A patient with pancreatic injury (n=1) was not included in the analysis, in order to ensure that the elevation observed in amylase and lipase levels was solely due to the non-pancreatic injury to abdomen.

Figure 2(a-b).

Location of organ injury and number of organs injured in patients with blunt trauma abdomen

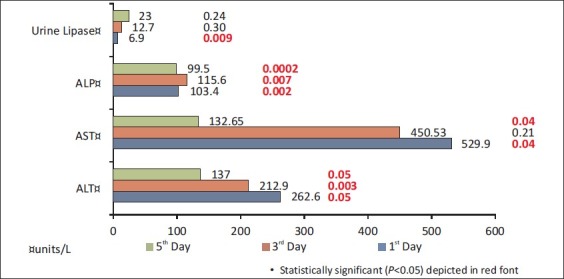

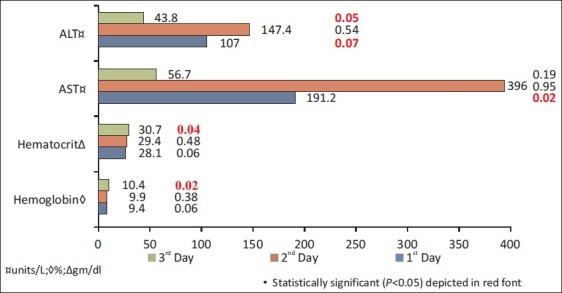

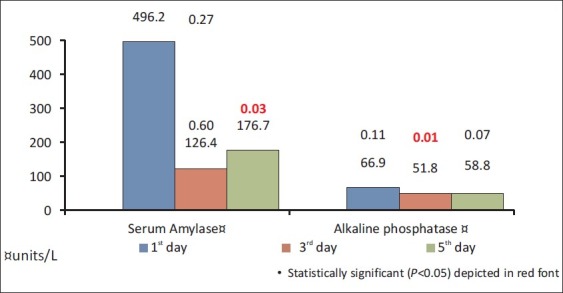

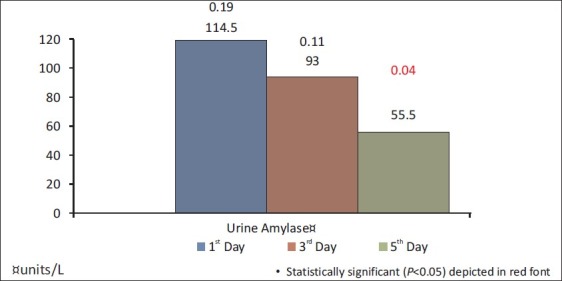

On analysis based on the location of intra-abdominal injury, several laboratory parameters were observed to be individually significant in assessing injury to a particular intra-abdominal organ. In patients who suffered liver injuries, urine lipase levels on day 1 (P value = 0.009), Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) (P value = 0.002), Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) (P value = 0.04), Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) (P value = 0.04), and urine lipase/amylase ratio (P value = 0.02), was found to be significant [Table 2, Figure 3]. Day 1 serum amylase (P value = 0.05), hemoglobin (P value= 0.03), and hematocrit (P value = 0.04); day 5 AST and ALT levels (P value = 0.02 and 0.04), were found to be significant in patients who had spleen injury [Figure 4]. Serum ALP levels on day 3 (P value = 0.01) and serum amylase levels on day 5 (P value = 0.04) were found to be significant in patients who had Gastrointestinal Tract (GIT) injury [Figure 5]. Urine amylase level on day 5 was statistically significant (P value = 0.04) in patients who had kidney injury [Figure 6].

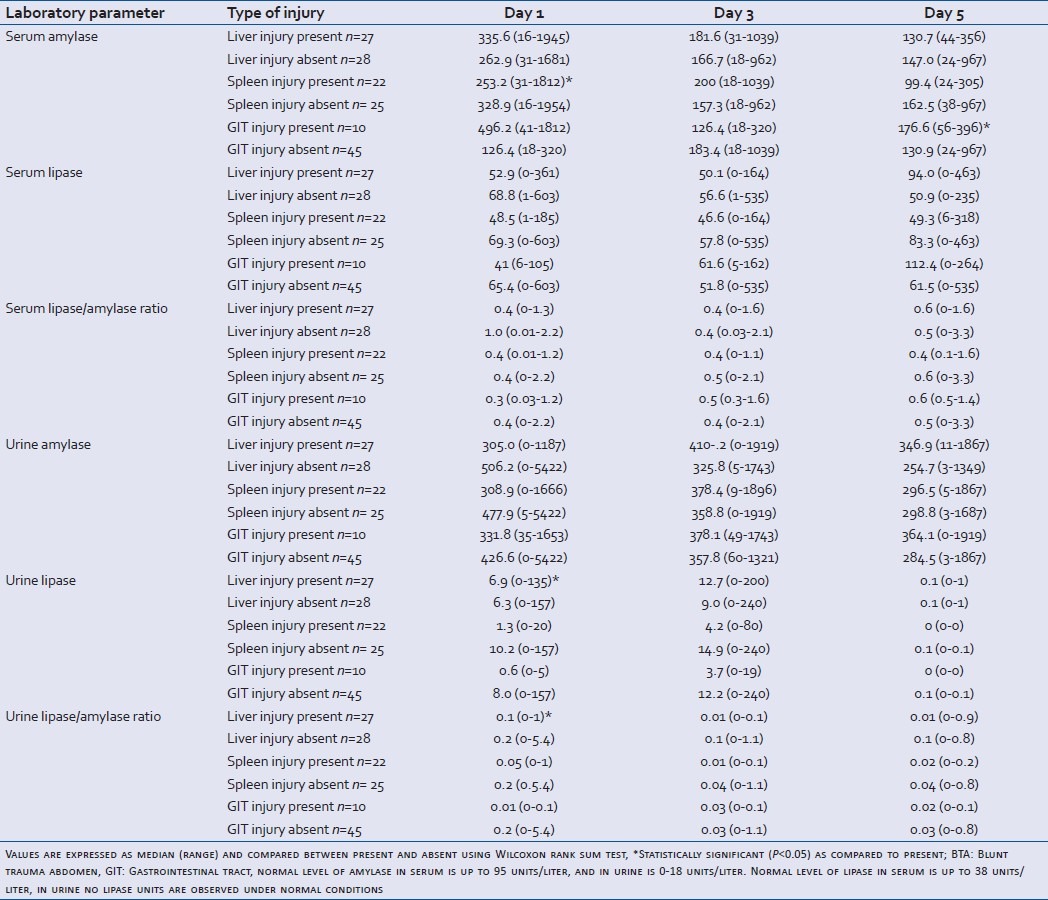

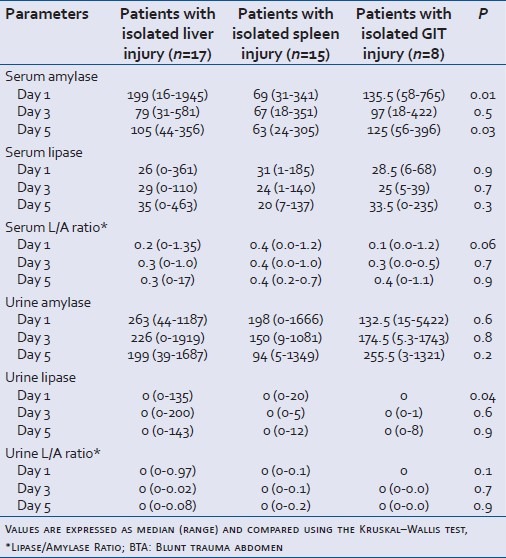

Table 2.

Relationship of serum and urine parameters with various intra-abdominal organs injured in BTA patients (liver, spleen, and GIT)

Figure 3.

Association of liver injury with laboratory parameters in patients with blunt trauma abdomen

Figure 4.

Association of spleen injury with laboratory parameters in patients with blunt trauma abdomen

Figure 5.

Association of gastrointestinal injury with laboratory parameters in patients with blunt trauma abdomen

Figure 6.

Association of renal injury with laboratory parameters in patients with blunt trauma abdomen

Influence of other associated injuries such as chest trauma, fracture pelvis, and head injury on BTA patients was also studied. Associated chest trauma influences the liver enzyme levels on day 1, namely, ALT (P value = 0.05) and ALP (P value = 0.05). Serum amylase for day 1 (0.03) and levels of lipase on day 5 (P value = 0.03), were found to be significant for patients with associated pelvic fractures and serum lipase/amylase ratio (0.02) was significant for patients with associated head injury.

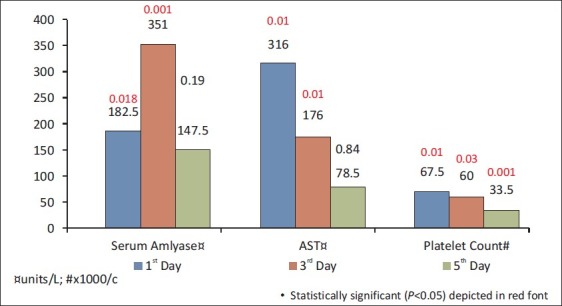

Association of the mechanism of injury and the organs injured was also analyzed, and was found to be statistically insignificant. Day 1 and 3 serum amylase levels (P value = 0.02 and 0.001, respectively), AST (P value = 0.02, 0.01) levels on day 1 & 3 and platelet count on day 1, 3, and 5 (P value = 0.02, 0.03, 0.001) were found to be significant in predicting the immediate outcome (dead/discharged) [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Correlation of mortality with laboratory parameters in blunt trauma abdomen patients

For observing the trend of amylase and lipase levels in serum as well as urine samples, univariate analysis was performed for isolated organ injury and multiple organ injury [Table 3].

Table 3.

Association of serum and urine parameters with the number of abdominal organ injured in BTA patients

Normal level of amylase in serum is up to 95 units/liter, and in urine is 0-18 units/liter. Normal level of lipase in serum is up to 38 units/liter; no lipase units are observed in urine under normal conditions.

In patients having a single intra-abdominal organ injury to the liver, spleen, and GIT, the levels of serum amylase recorded on days 1 and 5 were found to be significant. The levels of urine lipase on the day of injury were found to be clinically significant in predicting blunt trauma injury to the abdomen as well. In patients with isolated organ injury to the liver or spleen, the levels of urine amylase are elevated in day 1 (within 24 hrs of admission) and the levels gradually decrease on days 3 and 5, whereas in BTA patients with injury to GIT, the urine amylase levels were observed to gradually increase on days 3 and 5.

DISCUSSION

Blunt trauma, is a type of physical trauma caused to a body part, either by impact, injury, or physical attack. The majority of blunt abdominal trauma is often attributed to road traffic collisions, in which rapid deceleration often propels the driver forward into the steering wheel or dashboard, causing contusions in less serious cases, or rupturing of internal organs due to briefly increased intraluminal pressure in more serious cases where speed or forward force is greater. Most injuries are caused by blunt trauma inducing lacerations of the liver and/or spleen, urological trauma, infarcted bowel, or reproductive organ damage during pregnancy. The organs injured due to BTA are gastrointestinal tract, renal, hepatic, and other organs such as spleen.

The diagnosis of blunt abdominal trauma is based on physical examination findings such as signs of peritoneal penetration, unexplained shock and ileus, organ evisceration, free gas on radiographic examination, or evidence of bacteria or plant debris followed by abdominocentesis or peritoneal lavage.

Increasing abdominal size can be a vital indication for intra-abdominal injury. In human adults, increase in girth by every inch may represent 500-1000 ml of blood.[8] Abdominal firmness and tenderness are significant clinical signs of peritoneal irritation by blood or intestinal contents.

The standard diagnostic tools that facilitate optimum management of blunt abdominal trauma include FAST, Ultrasound of the Abdomen (USG), diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL), and CT scan.

FAST is valuable in the preliminary detection of free intraperitoneal or pericardial fluid, which usually occurs due to hemorrhage. DPL is used for diagnosis of internal abdominal injury when ultrasound machine is unavailable, or in the absence of trained personnel to perform FAST, or if the results of FAST are vague or difficult to interpret in a hemodynamically unstable patient. In contrast, in hemodynamically stable patients, CT with intravenous contrast is performed as it is constructive to detect free air and intraperitoneal fluid, delineate the extent of solid organ injury, detect retroperitoneal injuries, and help in the decision for conservative treatment.

Various other laboratory tests are also performed as indicators for further diagnostic testing for blunt trauma abdominal injuries, eg, serum amylase and lipase, urine amylase and lipase, liver function test, urine, RBC count, etc. An increase in serum amylase level along with lipase level is usually a marker for pancreatic injury.[9,10] Several traumatic, obstructive, inflammatory, and systemic diseases induce the release of lipolytic enzymes of non-pancreatic origin. The major sources of non-pancreatic lipase are liver, stomach, and intestine.[5]

Amylase may be released into the circulation as a result of damage to tissues containing high levels of the enzyme, or by escaping from the GIT. An elevation in the levels of amylase levels is seen mainly due to pancreatitis (inflammation/swelling of the pancreas), cholecystitis (inflammation/swelling of the gall bladder), infection or inflammation of salivary glands; moreover, obstruction of the bile or pancreatic duct and bowel can lead to direct diffusion of lipase from the intestinal lumen into the bloodstream.[11,12] Isolated increases in serum lipase can therefore be explained by the release of lipolytic enzymes of non-pancreatic origin into the general circulation. Hypoperfusion and inflammatory processes associated with multiple organ failure appears to be contributing to these increases. Lipase is removed from the circulation by glomerular filtration, followed by reabsorption and metabolism by the renal tubules.[11,13,14] Amylase is also eliminated by glomerular filtration and partially reabsorbed in the proximal tubule. An impaired renal function leads to increases in lipase level. A comparison of six different pancreatic enzymes by Seno et al. showed that lipase is less influenced by impaired renal function than amylase.[15] We observed the elevation in urine amylase levels to be clinically significant in patients with kidney injury. Lipase levels were chosen for this study because they normalize less rapidly than amylase levels.

Earlier studies have proved the role of amylase and lipase estimation as a screening diagnostic tool for detection of acute pancreatitis. However, sparse literature is available on the role of amylase and lipase levels in serum and urine to help predict specific intra-abdominal extra-pancreatic injuries after BTA.

The autodigestion hypothesis suggests that intraluminal pancreatic digestive enzymes enter the gut submucosa during periods of splanchnic ischemia, causing the local production of inflammatory mediators that are then transported into the systemic circulation by the mesenteric lymph.[16] A natural extension of this hypothesis is that a portion of these intraluminal pancreatic enzymes is also absorbed beyond the submucosa, and into the mesenteric lymph or venous circulation, leading to elevated serum enzyme levels.[4]

A study has been done on serum amylase levels in blunt injury to the pancreas regarding its significance and limitations.[7] The authors concluded that the most important factor influencing the serum amylase level at the time of admission in patients with blunt injury to pancreas is the time elapsed from injury to admission. Determination of serum amylase level was not diagnostic within 3 hours or fewer after trauma, irrespective of the type of injury. Therefore, to avoid failure in the detection of pancreatic injury, the amylase levels should be done more than 3 hours after trauma. The authors also suggested the possibility that serum amylase levels done on admission after 3 hours might be helpful to physicians to differentiate between type I and type III injury to the pancreas.

Mayer et al.[17] have supported and added to the above observations through their study on pancreatic injury in severe trauma. They have also strongly recommended the inclusion of serum amylase (or lipase) to the routine laboratory parameters after trauma. In their study, the diagnosis of a pancreatic lesion requiring surgical therapy was established later in 11 (28%) patients in whom primary emergency laparotomy was not done. Of these 11 patients, 6 had an increase in serum amylase levels within 48 hours after trauma.

Simon et al.[18] have suggested in their study of pediatric patients that serum amylase levels may be useful as an adjunct to abdominal CT scan and USG in cases with a significant history of subacute abdominal pain. Serum amylase determinations may also be possibly useful for observing the clinical course of patients with pancreatitis. However, they may be of limited use in the immediate management of pediatric patients, and hence suggested avoiding the routine ordering of serum amylase determinations in the above clinical scenario.

Holmes et al.[19] conducted a study to determine the utility of the emergency department physical examination and laboratory analysis in screening hospitalized pediatric blunt trauma patients for intra-abdominal injuries. The patients were divided into high- and low-risk categories. In their analysis, they showed that in the moderate-risk patients who had intra-abdominal injuries, there was a higher incidence of abdominal abrasions, an abnormal chest examination, higher mean serum concentrations of AST and ALT, higher mean white blood cell counts, and a higher prevalence of >5 RBCs/High Power Field (HPF) on urine analysis. However, there was no significant difference between moderate-risk patients with and without intra-abdominal injuries in initial serum concentrations of amylase, initial hematocrit, drop in hematocrit>5 percentage points, or initial serum bicarbonate concentrations.

The same is echoed by an earlier investigation by Isaacman and colleagues,[20] in which a negative urine analysis and a normal physical examination had a negative predictive value of 100%.

Cotton et al.[21] in their study on the utility of clinical and laboratory data for predicting intra-abdominal injury among children found that physical examination combined with hepatic serum transaminase may be a useful and easily applied clinical screen for predicting the presence or absence of intra-abdominal injury. According to their data, the decision to obtain an abdominal CT scan for stable children with normal abdominal examination results can be based on the results of a screening laboratory panel, which includes hepatic transaminase. Children with a low likelihood of intra-abdominal injury based on this screening method can be kept under observation. Thus, this protocol can reduce the use of abdominal CT scan among injured children while leading to an acceptably low rate of delayed intra-abdominal injury recognition.

Unlike Holmes et al.,[19] in our studies, the patients were grouped based on isolated or multiple injuries of the intra-abdominal organs. We observed that high levels of AST and ALT were clinically significant in detecting blunt trauma injuries to the liver and GIT.

However, there are other studies also that have either condemned or raised doubt on the usefulness or cost-effectiveness of serum amylase levels.

Adamson et al.[22] have shown in their study that determination of serum amylase and lipase levels may support clinical suspicion in the diagnosis of pediatric pancreatic trauma but are not reliable or cost-effective as screening tools. They have advocated that the cost incurred from routine serum amylase and lipase or from imaging tests subsequent to evaluation of serum values may be significant and unjustified. They have also refuted the prediction of severity of injury to the pancreas by the magnitude of serum amylase elevation.

Buechter et al.[23] carried out a study to determine the usefulness of serum amylase and lipase in the initial evaluation and subsequent management of blunt abdominal trauma patients. They collected serum amylase and lipase samples from 85 consecutive BTA patients at admission and days 1, 3, and 7. There was no correlation between amylase or lipase values and age, sex, type of injury, diagnostic tests, whether operation done, and outcome.

Capraro et al.[24] evaluated the use of routine laboratory studies as screening tools in pediatric abdominal trauma patients. They determined the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value for each test, using abdominal pathology identified by CT scan as the gold standard. They concluded the study with the finding that routine trauma panels should not be obtained as a screening tool in children with blunt trauma being evaluated for intra-abdominal injury.

Hence, there is no consensus on the studies done on BTA patients being evaluated for intra-abdominal injury using laboratory tests, especially serum amylase and lipase. Till date, the function of laboratory tests in the initial assessment and subsequent management of these blunt trauma patients is controversial.

Unlike Buechter et al.,[23] in our study, it was observed that elevation in amylase and lipase levels in serum and urine sample may be significant in detecting isolated organ injury.

Further, a majority of studies are on pediatric population and only few studies have been conducted on adult trauma patients. This study was done on patients of all ages and the estimation of urine lipase makes it a pioneer study.

CONCLUSION

Our aim was to evaluate whether amylase and lipase in serum and urine have discriminating abilities to predict the site of injury to the abdomen, even though these are not cost-effective routine diagnostic screening tools for extra-pancreatic injuries. Amylase levels in serum and urine as well as urine lipase when coupled with other laboratory tests may be significant in detecting intra-abdominal injury.

However, a study with a greater sample size is required to further ascertain the role of amylase and lipase in the diagnosis of intra-abdominal injuries in patients with blunt trauma.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Kanchana Rangarajan, Senior Resident, for providing continuous guidance and support. We are also grateful to Ashish Upadhayaya Dutta, Assistant Statistician, Department of Statistics, AIIMS, for his help in statistical analysis of this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tsui CL, Fung HT, Chung KL, Kam CW. Focused abdominal sonography for trauma in the emergency department for blunt abdominal trauma. Int J Emerg Med. 2008;1:183–7. doi: 10.1007/s12245-008-0050-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong YC, Wang LJ, Fang JF, Lin BC, Ng CJ, Chen RJ. Multidetector-row computed tomography (CT) of blunt pancreatic injuries: Can contrast-enhanced multiphasic CT detect pancreatic duct injuries? J Trauma. 2008;64:666–72. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31802c5ba0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valentino M, Serra C, Pavlica P, Labate AM, Lima M, Baroncini S, Barozzi L. Blunt abdominal trauma: Diagnostic performance of contrast-enhanced US in children-initial experience. Radiology. 2008;246:903–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2463070652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malinoski DJ, Hadjizacharia P, Salim A, Kim H, Dolich MO, Cinat M, et al. Elevated serum pancreatic enzyme levels after hemorrhagic shock predict organ failure and death. J Trauma. 2009;67:445–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181b5dc11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank B, Gottlieb K. Amylase normal, lipase elevated: Is it pancreatitis. A case series and review of the literature? Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:463–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.878_g.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nick WV, Zollinger RW, Williams RD. The diagnosis of traumatic pancreatitis with blunt abdominal injuries. J Trauma. 1965;5:495–502. doi: 10.1097/00005373-196507000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takishima T, Sugimoto K, Hirata M, Asari Y, Ohwada T, Kakita A. Serum amylase level on admission in the diagnosis of blunt injury to the pancreas: Its significance and limitations. Ann Surg. 1997;226:70–6. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199707000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson RF. Trauma. In: Shoemaker WC, Thompson WL, editors. Textbook of Critical Care. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1984. pp. 877–914. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meilstrup JW. Imaging Atlas of the Normal Gallbladder and Its Variants. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1994. p. 4. ISBN 0-8493-4788-2. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vlodov J, Tenner SM. Acute and chronic pancreatitis. Prim Care. 2001;28:607–28. doi: 10.1016/s0095-4543(05)70056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tietz NW. Support of the diagnosis of pancreatitis by enzyme tests—old problems, new techniques. Clin Chim Acta. 1997;257:85–98. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(96)06435-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gumaste VV, Roditis N, Mehta D, Dave PB. Serum lipase levels in nonpancreatic abdominal pain versus acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:2051–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tietz NW, Shuey DF. Lipase in serum-the elusive enzyme: An overview. Clin Chem. 1993;39:746–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong EC, Butch AW, Rosenblum JL. The clinical chemistry laboratory and acute pancreatitis. Clin Chem. 1993;39:234–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seno T, Harada H, Ochi K, Tanaka J, Matsumoto S, Choudhury R, et al. Serum levels of six pancreatic enzymes as related to the degree of renal dysfunction. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:2002–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmid-Schönbein GW, Hugli TE. A new hypothesis for microvascular inflammation in shock and multiorgan failure: Self-digestion by pancreatic enzymes. Microcirculation. 2005;12:71–82. doi: 10.1080/10739680590896009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayer JM, Tomczak R, Raua B, Gebhardc F, Beger HG. Pancreatic injury in severe trauma: Early diagnosis and therapy improve the outcome. Dig Surg. 2002;19:291–9. doi: 10.1159/000064576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simon HK, Muehlberg A, Linakis JG. Serum amylase determinations in pediatric patients presenting to the ED with acute abdominal pain or trauma. Am J Emerg Med. 1994;12:292–5. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(94)90141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmes JF, Sokolove PE, Land C, Kuppermann N. Identification of intra abdominal injuries in children hospitalized following blunt torso trauma. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:799–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb01210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Isaacman DJ, Scarfone RJ, Kost SI, Gochman RF, Davis HW, Bernardo LM, et al. Utility of routine laboratory testing for detecting intra- Abdominal injury in the pediatric trauma patient. Pediatrics. 1993;92:691–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cotton BA, Beckert BW, Smith MK, Burd RS. The utility of clinical and laboratory data for predicting intra-abdominal injury among children. J Trauma. 2004;56:1068–75. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000082153.38386.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adamson WT, Hebra A, Thomas PB, Wagstaff P, Tagge EP, Othersen HB. Serum amylase and lipase alone are not cost-effective screening methods for pediatric pancreatic trauma. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:354–7. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2003.50107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buechter KJ, Arnold M, Steele B, Martin L, Byers P, Gomez G, et al. The use of serum amylase and lipase in evaluating and managing blunt abdominal trauma. Am Surg. 1990;56:204–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Capraro AJ, Mooney D, Waltzman ML. The use of routine laboratory studies as screening tools in pediatric abdominal trauma. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:480–4. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000227381.61390.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]