Abstract

Lymphatic malformations and lymphatic-derived tumors commonly involve the head and neck, where they may be associated with bony abnormalities and other systemic symptoms. The reasons for the association between these disorders and local skeletal changes are largely unknown, but such changes may cause significant disease-related morbidity. Ongoing work in molecular and developmental biology is beginning to uncover potential reasons for the bony abnormalities found in head and neck lymphatic disease; this article summarizes current knowledge on possible mechanisms underlying this association.

Introduction

Lymphatic malformations are congenital vascular anomalies derived from lymphatic vessels and, for unexplained reasons, are associated with bone abnormalities. They occur most commonly in the head and neck and have an overall incidence of 1 in 2000 to 4000 live births.1 Clinical experience shows that lymphatic malformations and other lymphatic-derived tumors (ie, kaposiform hemangioendothelioma) are often associated with a wide range of skeletal abnormalities, which are particularly noticeable in the head and neck. These abnormalities include bony hypertrophy and progressive bone loss.2,3 Why lymphatic malformations are found near bony changes is not known, and diverse mechanisms have been proposed, including mechanical forces, intraosseous extensions of lymphatic malformations, and more recently endothelial- and extracellular matrix-driven abnormalities in bone development.2,4–6

Despite this clinical experience, no recent study has directly examined the interaction between lymphatic malformations and the craniofacial skeleton. In general, blood vessel development can be divided into vasculogenesis, or the de novo formation of blood vessels, and angiogenesis, or the branching of new vessels from existing vessels. These processes are closely tied to the environment in which they happen and are influenced by the extracellular matrix and other tissues nearby.6 These relationships are discussed briefly later in this article.

In contrast, little is known about which signals, if any, might link lymphatic vessel formation and development, and lymphatic malformations, to skeletal changes. This review summarizes the clinical presentation of bone disease and lymphatic malformations and current molecular signaling pathway evidence that may link these conditions. The goal is to direct future research on bony anomalies in lymphatic malformation patients.

Clinical Background

Histologically, the anatomic association of lymphatics and bone is unclear. Histopathologic studies including staining for lymphatic-specific markers such as LYVE-1 and podoplanin suggest that normal lymphatic vessels are not found within cortical bone, cancellous bone, or remodeling bone, but do occur in connective tissue overlying normal periosteum and perichondrium.7,8 However, at least one study, performed prior to availability of lymphatic-specific immunostains, demonstrated apparent endothelium–intraosseous lymphatic malformations in two thirds of mandible bone specimens from patients with cervicofacial lymphatic malformations.5 The presence of presumed lymphatic channels in bone that is either hypertrophic or shows progressive disappearance is not associated with increased levels of cell turnover or osteocyte activity (personal communication, Paula North).

Despite the lack of strong histopathologic evidence for close association between lymphatics and normal bone, various lymphatic-derived vascular anomalies are associated with skeletal abnormalities, including lymphatic malformations,9 Gorham-Stout syndrome/lymphangiomatosis,3 and kaposiform hemangioendothelioma.10 The nature of the abnormal lymphatic and blood vessels is not well-understood in all of these conditions.11 However, in all cases, lymphatic tumors adjacent to facial skeletal and skull bone can be associated with osteolysis and progressive bony loss3,12 (Figs. 1 and 2). Bone loss results in localized breakdown of normal structures and problems with loss of normal bony protection and support of vital structures such as the brain and spine. This can cause rhinogenic or otogenic meningitis and an unstable skull or cervical spine (Figs. 3A–3D). More commonly, congenital lymphatic malformations are associated with bony distortion and hypertrophy, but not with changes in bone density2 (Fig. 4). Debulking such lesions does not slow bony overgrowth,5 suggesting that a simple mechanical effect is not sufficient to explain skeletal changes in lymphatic disorders. This review describes several possible molecular mechanisms that might be pertinent to understanding these clinical findings.

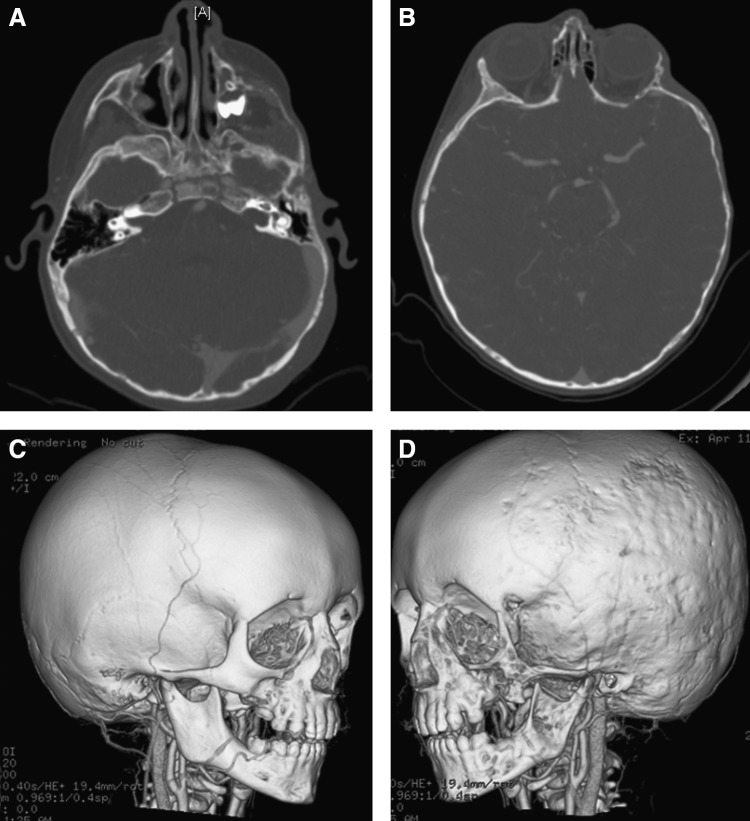

FIG. 1.

Coronal magnetic resonance image of lymphatic malformation adjacent to cranial bone and in upper neck that was associated with progressive skull bone loss and spinal instability.

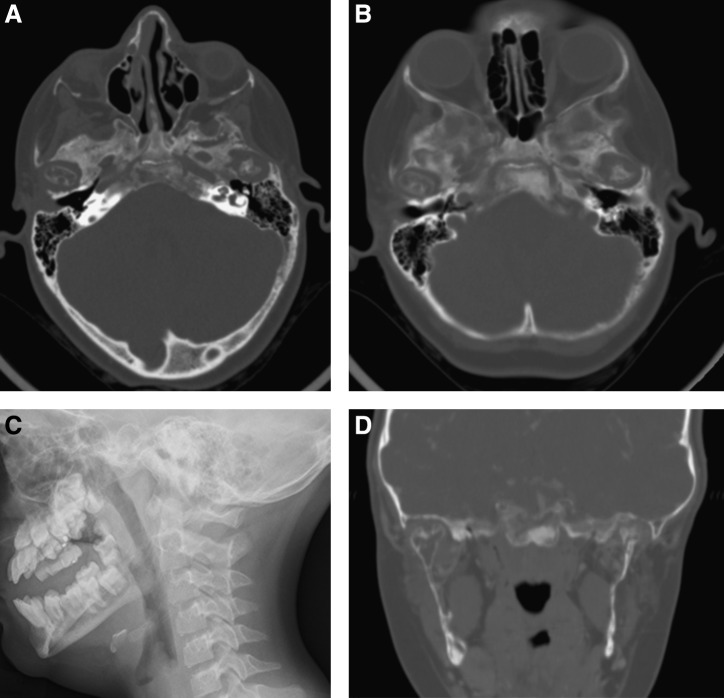

FIG. 2.

Craniofacial skeletal bone loss in patient with lymphatic malformation adjacent to the involved bone. (A) Axial high resolution computerized tomography (CT) images through the zygoma and zygomatic arch, demonstrating bone loss. (B) Axial CT showing cranial bone thinning on the same side. (C) Three-dimensional CT rendering of relatively normal side of cranium and facial skeleton. (D) Three-dimensional CT rendering of abnormal side of cranium and facial skeleton, demonstrating bone loss.

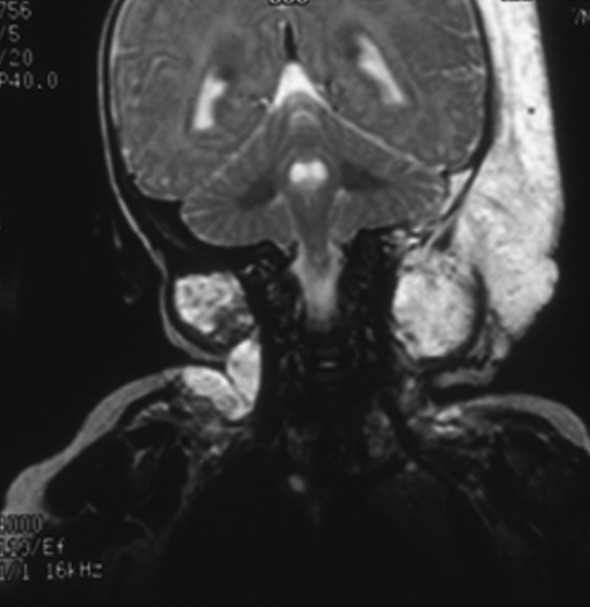

FIG. 3.

Progressive skull base and mandibular bone loss in patient with head and neck kaposiform hemangioendothelioma. (A) Axial high resolution computerized tomography (CT) images through the mandibular condyles demonstrating decalcification in the condyles and adjacent skull base. (B) Follow-up CT 2 years later. (C) Lateral facial plain film demonstrating absence of mandibular rami. (D) Coronal CT images of same area, demonstrating decalcification in the mandibular rami and condyles.

FIG. 4.

Mandibular hypertrophy in patient with lymphatic malformation; three-dimensional CT rendering.

When bone abnormalities are present in either lymphatic malformations or other lymphatic tumors, other systemic findings can also be present. These may include asymptomatic long bone lesions (Fig. 5). Cystic splenic lesions can develop, and may or may not be associated with chylothorax (Fig. 6). When skull base bone loss occurs, recurrent meningitis and unusual headache symptoms can occur, as previously mentioned,12 Additionally, extensive lymphatic malformations involving the oral cavity and pharynx can also be associated with lymphopenia and recurrent infection.13,14

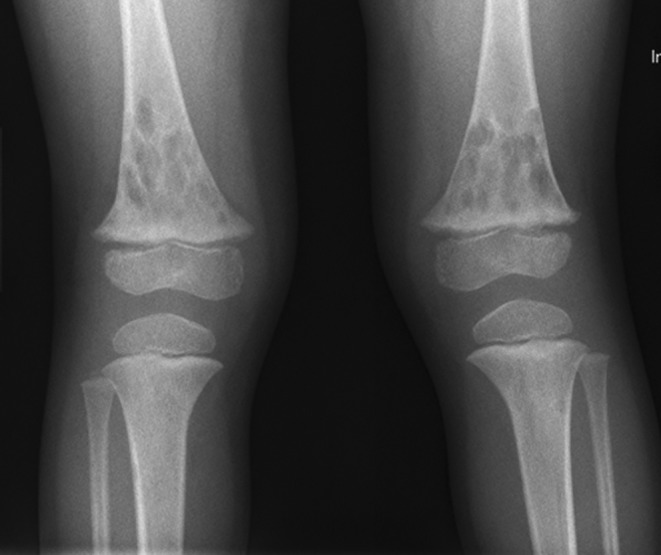

FIG. 5.

Asymptomatic long bone lesions in patient with progressive cranial bone loss and a head and neck lymphatic malformation.

FIG. 6.

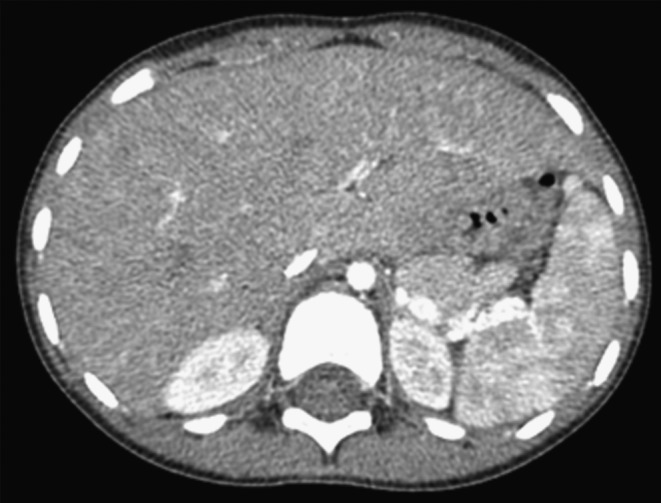

Splenic cystic changes in patient with lymphatic malformation and facial bone lesions.

General Context

Bone and blood vessel development and remodeling are constant ongoing processes through the life of an organism. These activities occur in the context of a dynamic extracellular matrix (ECM) which both influences, and is influenced by, these processes. The ECM can play both mechanical and biochemical roles6,15 in these activities, with the mechanical and biochemical overlapping significantly, for example, through the biochemical effects of ECM elasticity and tension on cell migration.6

The role of the ECM in development has been particularly well studied for branching structures such as the lung and salivary gland16 and in blood vessel development, all which are intimately associated with ECM remodeling through enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases.6 With regard to angiogenesis, for example, ECM both plays a physical scaffold-like role to guide vessel formation and expresses signals such as integrins that affect the organization of individual endothelial cells into tubular structures and the stability of these larger structures.17

Furthermore, the role of the ECM in and around bone, and with regard to vascular structures around bone, is particularly relevant to this article. The ECM acts to ensure correct directionality of signals between growing tissues and target regions and to induce regression of some tissues to ensure overall correct skeletal patterning.6 It then affects the differentiation of chondrocytes that form cartilage to allow subsequent endochondral ossification6 and finally constitutes the mineralized portions of mature bone.

As mentioned earlier, the ECM both affects and is affected by such processes, and as such may link both bone and blood vessel development. For example, in bone development and fracture healing in mice, osteoblast precursor cells are intimately associated with blood vessels and may even form pericyte-like cells as these vessels invade ossifying tissue, while vascular invasion leads to the formation of primary ossification centers.18

If any of these processes should not proceed normally, disease may ensue. For example, abnormalities in ECM may lead to congenital defects in the patterning of vascular or skeletal progenitor tissues, leading to subsequent phenotypic anomalies. It is conceivable that such abnormalities in ECM–bone–vessel interactions, for example in matrix metalloproteinase function, might lead to the linkage between lymphatic-derived tumors and skeletal changes.

Specific Molecular Pathways

Both blood vascular and lymphatic endothelial cells are derived from the embryonic somite.19 A great deal of published research examines molecular factors playing a role in blood vessel development; this data will not be examined in this review. Relatively little research has specifically examined which factors might influence lymphatic vessel development either in normal tissue or in congenitally diseased tissue. Almost no research has directly examined factors that might affect both lymphatic and bony development to explain the association between lymphatic disorders and skeletal changes. The next several sections examine those signals which have been shown to play a role in both blood vessel and bone development and summarize the evidence for their roles, if any, in lymphatic development. These signals are not mutually exclusive and may well play overlapping roles in this process, possibly in combination with other effects mediated by the ECM as described earlier.

Vascular endothelial growth factor

The family of vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF) are well-known angiogenic factors15,20 that influence the formation of blood vessels in both normal and pathologic soft tissue, both during development and later in life.21–23 These effects are complex and both direct and indirect, with VEGF able to prime vascular progenitor cells to receive angiogenic cytokine signals.24

VEGF also appear to play a role in bone formation via endochondral ossification and bony remodeling. Both osteoblasts and osteoclasts express VEGF receptors, and chondrocytes can express VEGF, which in turn promote angioinvasion into cartilage that will eventually ossify.15 VEGF itself plays a role in osteoclastogenesis25 and thus likely in bony remodeling. Furthermore, inhibition of VEGF delays ossification, resulting in thickening of epiphyseal growth plates and impaired trabecular bone formation.15 In distraction osteogenesis, VEGF-A, -B, -C, -and –D are all induced, as are VEGF receptors 1–3.26 This last study also demonstrated that blockade of VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 inhibited osteogenesis but did not examine VEGFR3. However, an earlier study showed that VEGF-D and VEGFR3 play a key role in osteoblast differentiation and osteogenesis.27

Of the multiple members of the VEGF family, VEGF-C and VEGF-D have been shown to be the most potent promoters of lymphangiogenesis, specifically.28–30 This promotion may occur in part through chemotactic attraction of lymphatic endothelial cells.31 The corresponding receptor, VEGF receptor 3 (VEGFR3),32 has demonstrated expression on lymphatic endothelial cell precursors33 and plays a role in lymphatic development.34 The same signals play a role in disease states. Tumor lymphangiogenesis appears to be largely mediated by VEGF-C and VEGF-D via VEGFR3.35,36 VEGF-C is highly expressed around the interface between bone and orthopedic implants, and some lymphatic vessels are found in this interface, although these vessels are rare.37 Meanwhile, VEGFR3 itself may play a role in the development of lymphatic malformations.38

Based on this evidence, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that VEGF and VEGFR, specifically VEGF-C and –D and VEGFR3, may link pathologic lymphatic development to bony remodeling. Further investigation into this question is warranted and, based on the evidence above, may be the most rewarding initial path of research compared to other possibilities discussed later in this review.

Matrix metalloproteinases

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) are enzymes, specifically endopeptidases, that cleave extracellular matrix proteins to allow endothelial sprouting and angiogenesis.6,15 The breakdown of matrix proteins both decreases mechanical obstacles to vessel sprouting and through various local molecular mechanisms.15 As described earlier, MMP are central in the invasion of branching and lumen-bearing structures into the surrounding ECM and provide a pathway by which the ECM may influence the development of these structures.17

Basic science data linking MMP to lymphatic development is scant but suggestive. ADAM8, a metalloproteinase, has been detected in developing cartilage and bone. It is also expressed in the mesenchyme surrounding the point at which developing lymphatic branch from the jugular vein. However, ADAM8 knockout animals had no detectable pathology at this site or any others,39 raising the question of whether these observed expression patterns may simply be coincidental.

In contrast, some clinical data support the role of MMP in lymphatic growth. One study of lymphangiogenesis in filarial disease demonstrated that filarial parasites selectively enhance lymphangiogenesis via elevated levels of MMPs as well as by inhibiting tissue inhibitors of MMP.40 These findings occurred in the absence of typical lymphangiogenic markers seen in tumors, suggesting that MMP play an independent role in lymphangiogenesis. Meanwhile, another study of MMP in patients with lymphatic malformations and other vascular anomalies demonstrated a higher urinary excretion of high molecular weight MMPs.41 The same study showed an association between higher urinary excretion of MMP and increased extent and clinical activity of lymphatic malformations. This association was not seen for VEGF. These findings strengthen the supposition that these enzymes might play a role in lymphatic diseases.

Meanwhile, MMP are also closely associated with skeletal growth, remodeling, and repair. This role is likely due to the ability of MMP to break down extracellular matrix as described above, allowing the formation of vascular channels containing hematopoietic cells, facilitating bone growth.42 In mice, treatment with GM6001, a general MMP inhibitor, specifically impaired bony repair and remodeling at fracture sites without affecting cartilage repair.43 Similar observations have been made in young mice treated with GM6001; these animals experience expansion of the cartilage at growth plates and absence of normal ossification.42

MMP expression is influenced by VEGF and other growth factors15 and is thus not independent of the pathways described in the last section. Conversely, MMP, specifically MMP9, may regulate the bioavailability of VEGF during skeletal growth and remodeling. When VEGF activity is blocked by a competitive soluble VEGF receptor, mice show expanded hypertrophic cartilage and decreased bone formation. MMP9-null mice show the same phenotype despite a 10-fold increase in VEGF expression.42 These findings suggest that MMP9 may be necessary for VEGF to properly participate in endochondral ossification.

As with VEGF, MMP form a plausible link between lymphatic tumors and nearby skeletal abnormalities. These two mechanisms are not independent and may both play a role in this clinical association.

Bone morphogenetic protein

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP) are members of the transforming growth factor β family.44 Various studies have demonstrated the importance of BMP in vascular development. BMP4 has been shown to promote the differentiation of cultured embryonic stem cells into capillary-like networks lined by mature endothelial cells,45 while BMP antagonists play key developmental roles in preventing local endothelial cell generation and organization into vascular networks.46

Meanwhile, BMP also play central roles in fetal and postnatal skeletal development.44 These molecules also may play a role in bony remodeling, having been identified in healing fracture callus.47 At a fundamental level of bone formation, BMP1 plays a role in the general production of collagen,48 which is required for bone formation. Meanwhile, BMP also may play a role in postnatal bone formation, as shown by the decreased in bone formation in mice expressing a dominant negative BMP receptor transgene.49

Despite playing a prominent role in the development of both blood vessels and bone, no published research to date has examined the possible role of BMP in lymphatic development or lymphatic tumors. This may be a rich area of investigation given the multiple roles these factors play in the skeletal and vascular systems.

Prox1

Prospero-related homeobox 1 (Prox1) is a transcription factor that is expressed by fetal lymphangioblasts19 and has been shown to be necessary for initial development of lymphatic vessels.50 Prox1 is specific to lymphatic development as opposed to blood vascular development50 and can induce expression of lymphatic endothelial cell genes even in blood vascular endothelium.29,36 This specificity is such that Prox1 has been used as a marker of lymphatic vessels in immunohistochemical studies (for example, reference 7). Prox1 appears to play this role in part through upregulation of VEGFR3 through binding with the VEGFR3 promoter,31,51,52 although the picture is complicated by associated downregulation of VEGF-C.51

Given this pivotal role, it seems reasonable that abnormalities in Prox1 can lead to lymphatic pathology. For example, lack of function in one Prox1 allele has been associated with obesity, specifically through accumulation of adipose tissue in areas of lymphedema caused by abnormal lymphatic vasculature.53 However, the published literature currently does not include any studies of Prox1 in lymphatic malformations or lymphatic tumors. Furthermore, no data are currently available on possible roles of Prox1 in bony development and remodeling. With its central role in normal lymphatic development and its interactions with VEGFR3, Prox1 appears to be another reasonable avenue of inquiry into the association between lymphatic tumors and skeletal anomalies.

Macrophages and inflammation

A final promising area of research is the role of macrophages and inflammation in connecting lymphatic pathology with bony abnormalities. Lymphatics are important in inflammation and tissue healing because they provide conduits for the arrival of cells participating in the inflammatory response, and because they actively drain away particular cells, molecules, and fluid from the area of inflammation.37,54

Macrophages involved in corneal inflammation have been shown to produce VEGF-C and VEGF-D, and local reductions in macrophage populations within inflamed mouse corneas dramatically inhibit local lymphangiogenesis.35 Similarly, cells staining for both macrophage and lymphatic markers play a role in healing of skin ulcers,54 and decreased macrophage recruitment to subcutaneous tissue is associated with decreased lymphatic vessel density and length.55

Meanwhile, the role of macrophages and inflammation in skeletal changes is less clear but no less interesting. Chronic inflammation is associated with impaired skeletal growth in children.56 In addition, complete absence of the adaptive immune system, which might otherwise activate macrophages, is associated with accelerated ossification of callus at fracture sites.57 These findings suggest that macrophages and inflammation might actually inhibit bony growth and remodeling. This supposition is relevant in that lymphatic malformation patients experience lymphopenia13,14 and thus may have a decreased inflammatory response, which in turn may facilitate skeletal remodeling both locally and systemically. However, in aortic atherosclerosis, macrophage burden is directly associated with osteogenic activity by osteoblasts.58 Similarly, rheumatic disease is associated with calcifications that show both macrophage activity and ectopic bone formation.59 These findings suggest an active role for macrophages in bone formation and calcification.

Conclusion

While a great deal of information has been published on links between the development of blood vessels and bone, very little data are available that directly examine the relationship between lymphatic development and pathology and bony changes. However, some available data does indirectly suggest mechanisms that may explain the clinically observed association between lymphatic malformations or other lymphatic tumors and changes in the bony skeleton. We have attempted to summarize this data in order to suggest potential avenues of research to the reader, with the understanding that research supporting these possibilities is still lacking. Of the pathways discussed here, VEGF and matrix metalloproteinases may have the most evidence currently available, but even these two mechanisms have undergone little study.

As clinical investigators look into the natural history, treatment outcomes, and impact of lymphatic malformations and less common lymphatic pathologies, new therapeutic interventions and better understanding of the molecular and genetic mechanisms underlying these diseases will be necessary. This review highlights some candidate mechanisms and will hopefully be of use to readers interested in lymphatic diseases.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Perkins JA. Manning SC. Tempero RM. Cunningham MJ. Edmonds JL., Jr Hoffer FA. Egbert MA. Lymphatic malformations: Review of current treatment. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;142:795–803. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd JB. Mulliken JB. Kaban LB. Upton J., III Murray JE. Skeletal changes associated with vascular malformations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;74:789–795. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198412000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee S. Finn L. Sze RW. Perkins JA. Sie KC. Gorham Stout syndrome (disappearing bone disease): Two additional case reports and a review of the literature. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:1340–1343. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.12.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osborne TE. Levin LS. Tilghman DM. Haller JA. Surgical correction of mandibulofacial deformities secondary to large cervical cystic hygromas. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;45:1015–1021. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(87)90156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padwa BL. Hayward PG. Ferraro NF. Mulliken JB. Cervicofacial lymphatic malformation: Clinical course, surgical intervention, and pathogenesis of skeletal hypertrophy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:951–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu P. Takai K. Weaver VM. Werb Z. Extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling in development and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011 Dec 1;3(12):pii:a005058. doi: 10.1101/cghperspect.a005058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards JR. Williams K. Kindblom LG. Meis-Kindblom JM. Hogendoorn PC. Hughes D. Forsyth RG. Jackson D. Athanasou NA. Lymphatics and bone. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin ZW. Nakamura T. Yu HC. Kimura W. Murakami G. Cho BH. Fetal anatomy of peripheral lymphatic vessels: A D2-40 immunohistochemical study using an 18-week human fetus (CRL 155mm) J Anat. 2010;216:671–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O TM. Kwak R. Portnof JE. Berke DM. Lipari B. Waner M. Analysis of skeletal mandibular abnormalities associated with cervicofacial lymphatic malformations. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:91–101. doi: 10.1002/lary.21161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zukerberg LR. Nickoloff BJ. Weiss SW. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma of infancy and childhood: An aggressive neoplasm associated with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome and lymphangiomatosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:321–328. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199304000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franchi A. Bertoni F. Bacchini P. Mourmouras V. Miracco C. CD105/endoglin expression in Gorham disease of bone. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:163–167. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.060160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cushing SL. Ishak G. Perkins JA. Rubinstein JT. Gorham-Stout syndrome of the petrous apex causing chronic cerebrospinal fluid leak. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31:789–792. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181de46c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tempero RM. Hannibal M. Finn LS. Manning SC. Cunningham ML. Perkins JA. Lymphocytopenia in children with lymphatic malformations. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:93–97. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perkins JA. Tempero RM. Hannibal MC. Manning SC. Clinical outcomes in lymphocytopenic lymphatic malformation patients. Lymphat Res Biol. 2007;5:169–174. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2007.5304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall AP. Westwood FR. Wadsworth PF. Review of the effects of anti-angiogenic compounds on the epiphyseal growth plate. Toxicol Pathol. 2006;34:131–147. doi: 10.1080/01926230600611836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daley WP. Peters SB. Larsen M. Extracellular matrix dynamics in development and regenerative medicine. J Cell Sci. 2007;121:255–264. doi: 10.1242/jcs.006064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis GE. Senger DR. Endothelial extracellular matrix: Biosynthesis, remodeling, and functions during vascular morphogenesis and neovessel stabilization. Circ Res. 2055;97:1093–1107. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000191547.64391.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maes C. Kobayashi T. Selig MK. Torrekens S. Roth SI. Mackem S. Carmeliet G. Kronenberg HM. Osteoblast precursors, but not mature osteoblasts, move into developing and fractured bones along with invading blood vessels. Dev Cell. 2010;19:329–344. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilting J. Becker J. Two endothelial cell lines derived from the somite. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2006;211:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s00429-006-0120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalal S. Berry AM. Cullinane CJ. Mangham DC. Grimer R. Lewis IJ. Johnston C. Laurence V. Burchill SA. Vascular endothelial growth factor: A therapeutic target for tumors of the Ewing's sarcoma family. Clin Cancer Res. 2055;11:2364–2378. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ria R. Vacca A. Russo F. Cirulli T. Massaia M. Tosi P. Cavo M. Guidolin D. Ribatti D. Dammacco F. A VEGF-dependent autocrine loop mediates proliferation and capillarogenesis in bone marrow endothelial cells of patients with multiple myeloma. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92:1438–1445. doi: 10.1160/TH04-06-0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reddy K. Cao Y. Zhou Z. Yu L. Jia SF. Kleinerman ES. VEGF165 expression in the tumor microenvironment influences the differentiation of bone marrow-derived pericytes that contribute to the Ewing's sarcoma vasculature. Angiogenesis. 2008;11:257–267. doi: 10.1007/s10456-008-9109-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grunewald M. Avraham I. Dor Y. Bachar-Lustig E. Itin A. Yung S. Chimenti S. Landsman L. Abramovitch R. Keshet E. VEGF-induced adult neovascularization: Recruitment, retention, and role of accessory cells. Cell. 2006;124:175–189. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stratman AN. Davis MJ. Davis GE. VEGF and FGF prime vascular tube morphogenesis and sprouting directed by hematopoietic stem cell cytokines. Blood. 2011;117:3709–3719. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-316752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka Y. Abe M. Hiasa M. Oda A. Amou H. Nakano A. Takeuchi K. Kitazoe K. Kido S. Inoue D. Moriyama K. Hashimoto T. Ozaki S. Matsumoto T. Myeloma cell–osteoclast interaction enhances angiogenesis together with bone resorption: A role for vascular endothelial cell growth factor and osteopontin. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:816–823. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobsen KA. Al-Aql ZS. Wan C. Fitch JL. Stapleton SN. Mason ZD. Cole RM. Gilbert SR. Clemens TL. Morgan EF. Einhorn TA. Gerstenfeld LC. Bone formation during distraction osteogenesis is dependent on both VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 signaling. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:596–609. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orlandino M. Spreafico A. Bardelli M. Rocchigiani M. Salameh A. Nucciotti S. Capperucci C. Frediani B. Oliviero S. Vascular endothelial growth factor-D activates VEGFR-3 expressed in osteoblasts inducing their differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17961–17967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600413200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rissanen TT. Markkanen JE. Gruchala M. Heikura T. Puranen A. Kettunen MI. Kholova I. Kauppinen RA. Achen MG. Stacker SA. Alitalo K. Yla-Herttuala S. VEGF-D is the strongest angiogenic and lymphangiogenic effector among VEGFs delivered into skeletal muscle via adenoviruses. Circ Res. 2003;92:1098–106. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000073584.46059.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ji R.-C. Lymphatic endothelial cells, lymphangiogenesis, and extracellular matrix. Lymphat Res Biol. 2006;4:83–100. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2006.4.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lohela M. Bry M. Tammela T. Alitalo K. VEGFs and receptors involved in angiogensis versus lymphangiogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:154–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mishima K. Watabe T. Saito A. Yoshimatsu Y. Imaizumi N. Masui S. Hirashima M. Morisada T. Oike Y. Araie M. Niwa H. Kubo H. Suda T. Miyazono K. Prox1 induces lymphatic endothelial differentiation via integrin α9 and other signaling cascades. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:1421–1429. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jussila L. Alitalo K. Vascular growth factors and lymphangiogenesis. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:673–700. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salven P. Mustjoki S. Alitalo R. Alitalo K. Rafii S. VEGFR-3 and CD133 identify a population of CD34+ lymphatic/vascular endothelial precursor cells. Blood. 2003;101:168–172. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ny A. Koch M. Vandevelde W. Schneider M. Fischer C. Diez-Juan A. Neven E. Geudens I. Maity S. Moons L. Plaisance S. Lambrechts D. Carmeliet P. Dewerchin M. Role of VEGF-D and VEGFR-3 in developmental lymphangiogenesis, a chemicogenetic study in Xenopus tadpoles. Blood. 2008;112:1740–1749. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-106302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cursiefen C. Chen L. Borges LP. Jackson D. Cao J. Radziejewski C. D'Amore PA. Dana MR. Wiegand SJ. Streilein JW. VEGF-A stimulates lymphangiogenesis and hemangiogenesis in inflammatory neovascularization via macrophage recruitment. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1040–1050. doi: 10.1172/JCI20465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kilic N. Oliveira-Ferrer L. Neshat 0. Vahid S. Irmak S. Obst-Pernberg K. Wurmbach J-H. Loges S. Kilic E. Weil J. Lauke H. Tilki D. Singer BB. Ergun S. Lymphatic reprogramming of microvascular endothelial cells by CEA-related cell adhesion molecule-1 via interaction with VEGFR-3 and Prox1. Blood. 2007;110:4223–4233. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-097592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jell G. Kerjaschki D. Revell P. Al-Saffar N. Lymphangiogenesis in the bone-implant interface of orthopedic implants: Importance and consequence. J Biomed Mater Res. 2006;77A:119–127. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilting J. Buttler K. Rossler J. Norgall S. Schweigerer L. Weich HA. Papoutsi M. Embryonic development and malformation of lymphatic vessels. Novartis Found Symp. 2007;283:220–227. doi: 10.1002/9780470319413.ch17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelly K. Hutchinson G. Nebenius-Oosthuizen D. Smith AJ. Bartsch JW. Horiuchi K. Rittger A. Manova K. Docherty AJ. Blobel CP. Metalloprotease-disintegrin ADAM8: Expression analysis and targeted deletion in mice. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:221–231. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennuru S. Nutman TB. Lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic remodeling induced by filarial parasites: Implications for pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000688. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marler JJ. Fishman SJ. Kilroy SM. Fang J. Upton J. Mulliken JB. Burrows PE. Zurakowski D. Folkman J. Moses MA. Increased expression of urinary matrix metalloproteinases parallels the extent and activity of vascular anomalies. Pediatrics. 2005;116:38–45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ortega N. Behonick D. Stickens D. Werb Z. How proteases regulate bone morphogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;995:109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lieu S. Hansen E. Dedini R. Behonick D. Werb Z. Miclau T. Marcucio R. Colnot C. Impaired remodeling phase of fracture repair in the absence of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Dis Model Mech. 2011;4:203–211. doi: 10.1242/dmm.006304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cao X. Chen D. The BMP signaling and in vivo bone formation. Gene. 2005;357:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boyd NL. Dhara SK. Rekaya R. Godbey EA. Hasneen K. Rao RR. West FD., III Gerwe BA. Stice SL. BMP4 promotes formation of primitive vascular networks in human embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies. Exp Biol Med. 2007;232:833–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bressan M. Davis P. Timmer J. Herzlinger D. Mikawa T. Notochord-derived BMP antagonists inhibit endothelial cell generation and network formation. Dev Biol. 2009;326:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kloen P. DiPaola M. Borens O. Richmond J. Perino G. Helfet DL. Goumans MJ. BMP signaling components are expressed in human fracture callus. Bone. 2003;33:362–371. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lesiak M. Augusciak-Duma A. Szydlo A. Sieron A. Blocking angiogenesis with peptides that inhibit the activity of procollagen C-endopeptidase. Pharmacol Rep. 2009;61:468–476. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(09)70088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao M. Harris SE. Horn D. Geng Z. Nishimura R. Mundy G. Chen D. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor signaling is necessary for normal murine postnatal bone formation. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:1049–1060. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wigle JT. Oliver G. Prox1 function is required for the development of the murine lymphatic system. Cell. 1999;98:769–778. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81511-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hong Y-K. Harvey N. Noh Y-H. Schacht V. Hirakawa S. Detmar M. Oliver G. Prox1 is a master control gene in the program specifying lymphatic endothelial cell fate. Dev Dyn. 2002;225:351–357. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoshimatsu Y. Yamazaki T. Mihira H. Itoh T. Suehiro J. Yuki K. Harada K. Morikawa M. Iwata C. Minami T. Morishita Y. Kodama T. Miyazono K. Watabe T. Ets family members induce lymphangiogenesis through physical and functional interaction with Prox1. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:2753–2762. doi: 10.1242/jcs.083998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harvey NL. Srinivasan RS. Dillard ME. Johnson NC. Witte MH. Boyd K. Sleeman MW. Oliver G. Lymphatic vascular defects promoted by Prox1 haploinsufficiency cause adult-onset obesity. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1072–1081. doi: 10.1038/ng1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maruyaama K. Asai J. Ii M. Thorne T. Losordo DW. D'Amore PA. Decreased macrophage number and activation lead to reduced lymphatic vessel formation and contribute to impaired diabetic wound healing. Am J Pathol. 2007;1270:1178–1191. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murakami M. Zheng Y. Hirashima M. Suda T. Morita Y. Ooehara J. Ema H. Fong G-H. Shibuya M. VEGFR1 tyrosine kinase signaling promotes lymphangiogenesis as well as angiogenesis indirectly via macrophage recruitment. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:658–664. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.150433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.De Benedetti F. The impact of chronic inflammation on the growing skeleton: Lessons from interleukin-6 transgenic mice. Horm Res. 2009;72:26–29. doi: 10.1159/000229760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Toben D. Schroeder I. El Khassawna T. Mehta M. Hoffmann JE. Frisch JT. Schell H. Lienau J. Serra A. Radbruch A. Duda GN. Fracture healing is accelerated in the absence of the adaptive immune system. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:113–124. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aikawa E. Nahrendorf M. Figueiredo JL. Swirski FK. Shtatland T. Kohler RH. Jaffer FA. Aikawa M. Weissleder R. Osteogenesis associates with inflammation in early-stage atherosclerosis evaluated by molecular imaging in vivo. Circulation. 2007;116:2841–2850. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.732867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rajamannan NM. Nealis TB. Subramaniam M. Pandya S. Stock SR. Ignatiev CI. Sebo TJ. Rosengart TK. Edwards WD. McCarthy PM. Bonow RO. Spelsberg TC. Calcified rheumatic valve neoangiogenesis is associated with vascular endothelial growth factor expression and osteoblast-like bone formation. Circulation. 2005;111:3296–3301. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.473165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]